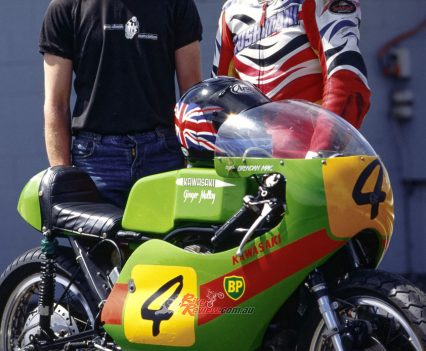

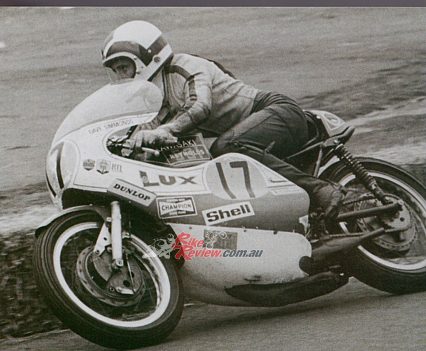

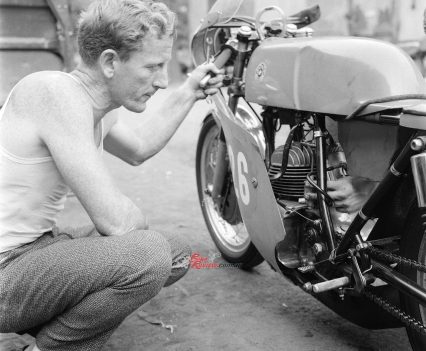

Cathcart managed to score a ride on one of the most important two-stroke machines ever. Check out his racer test on-board the Ginger Molloy Kawasaki H1R... Photo credit: Kel Edge

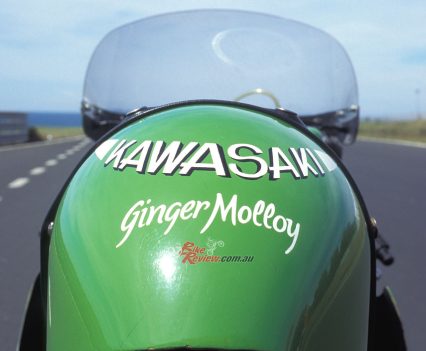

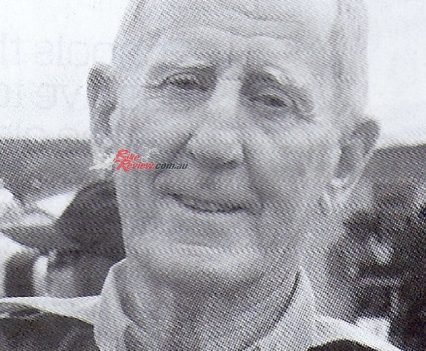

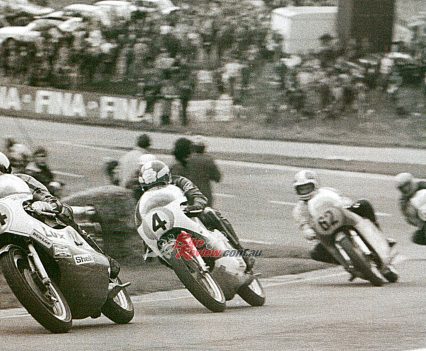

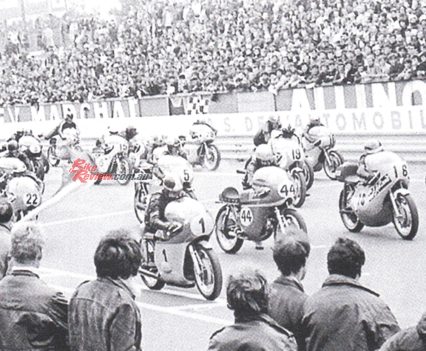

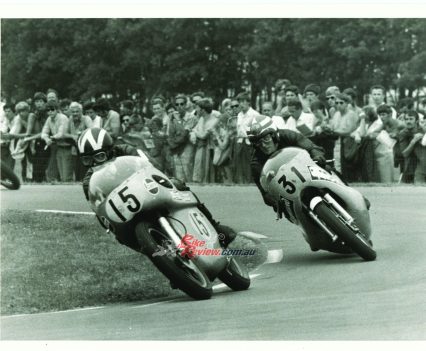

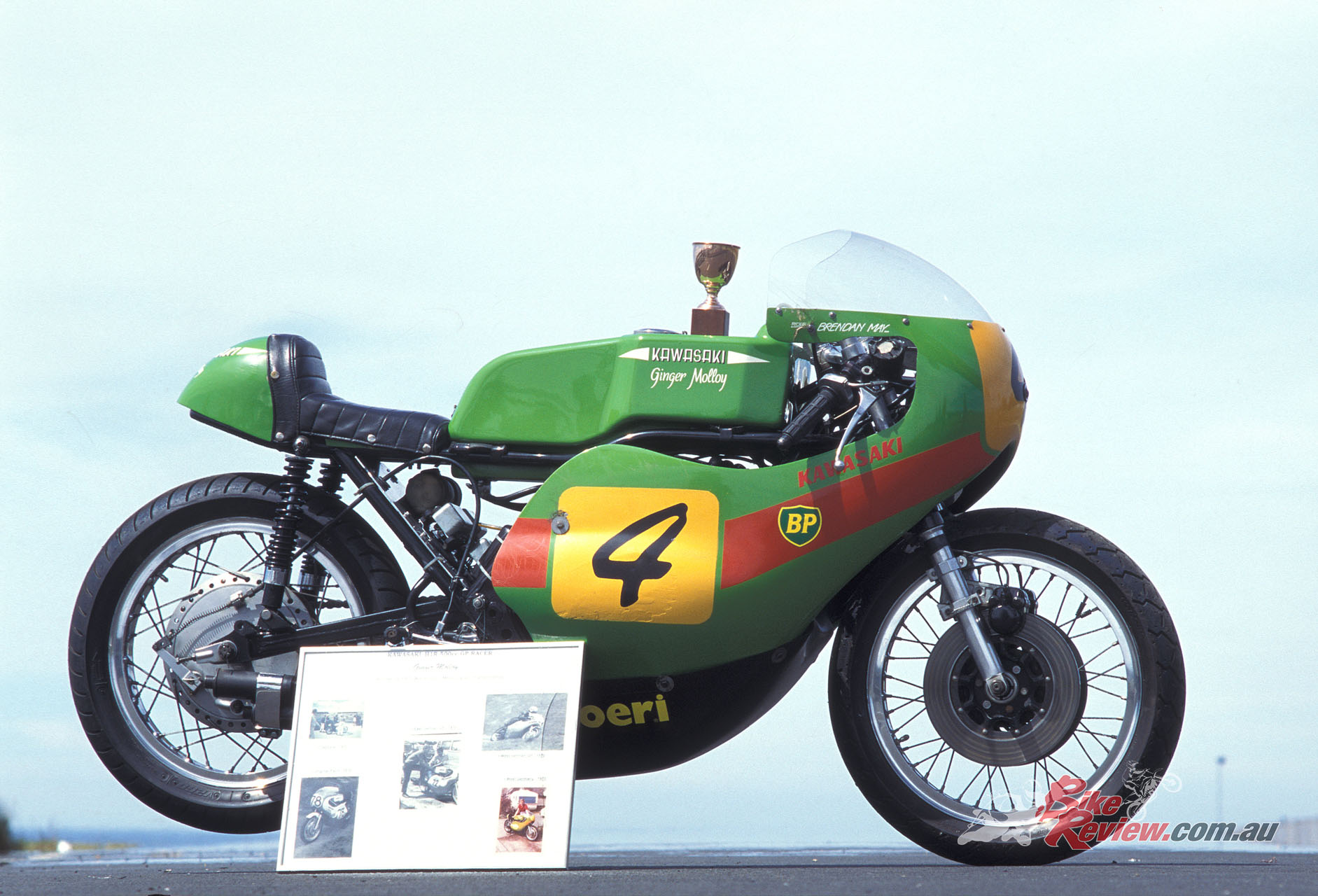

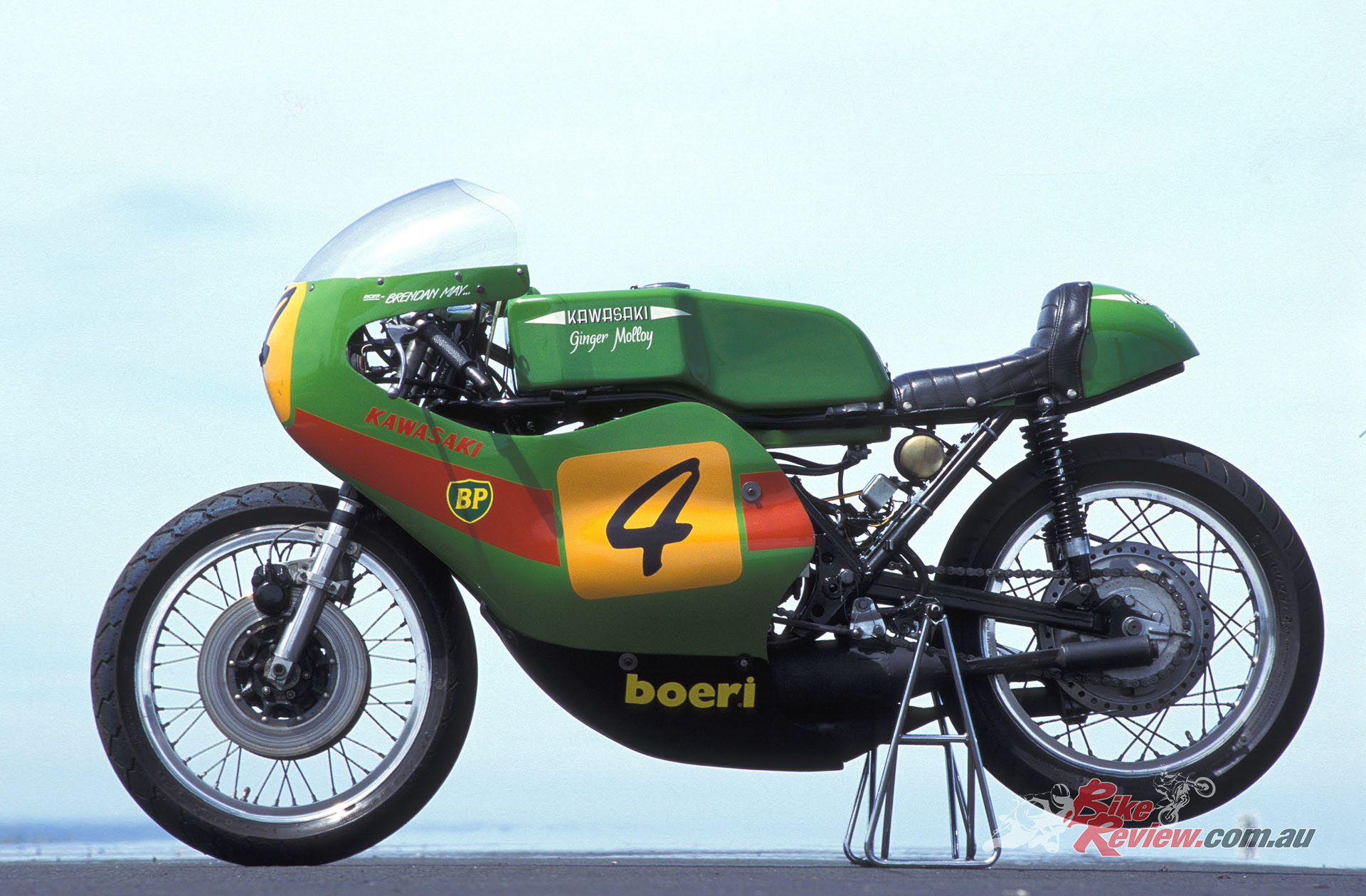

50 years on from its season in the sun, Ginger Molloy’s milestone Kawasaki H1R is alive and racing in Australia in completely original form, thanks to the son of the man who acquired the bike from Ginger in 1972. What an important bike this is for the sport…

50 years on from its season in the sun, Ginger Molloy’s milestone Kawasaki H1R is alive and well and racing in Australia in completely original form.

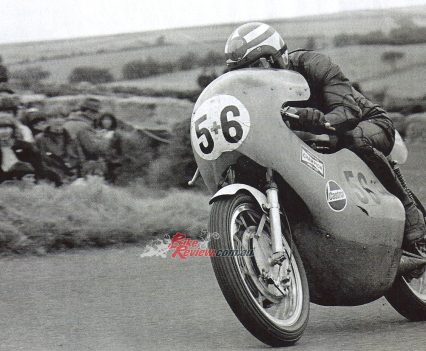

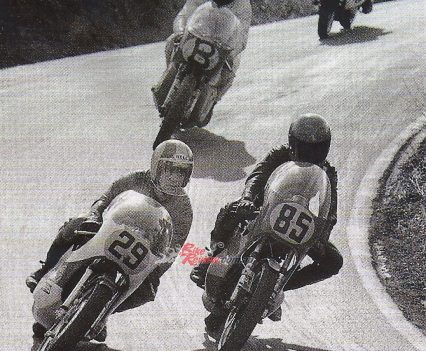

For Brendan May and his brother Brad took over the 500GP World championship runner-up H1R from their dad Kevin in 1983, ten years after he’d bought it from Molloy. The Kiwi had spent 1971 racing in the USA, then returned Down Under to finish second on the bike in the Australian TT at Bathurst, where the Kawasaki was clocked at an incredible 276KM/H down the Conrod Straight, running 13,000rpm on its tallest gearing – without any damage!

Read about the history of the Molloy H1R here…

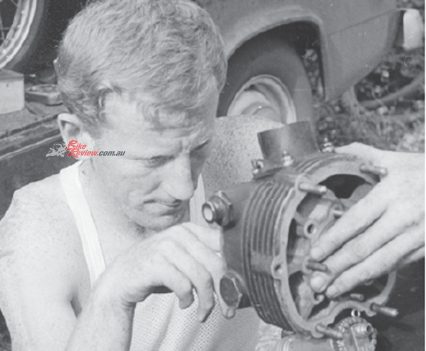

That was Ginger’s racing swansong, after which he rebuilt the bike and sold it to the May family, then retired from racing to become a Honda dealer in his NZ homeland (though he later became an active competitor in Historic events on his Bultacos!). Brendan May used the Kawasaki GP racer to progress through C-grade novice racing, before running out of pistons and breaking the skirt off the centre cylinder, leading him to park it and move on to a modern 250 Yamaha.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

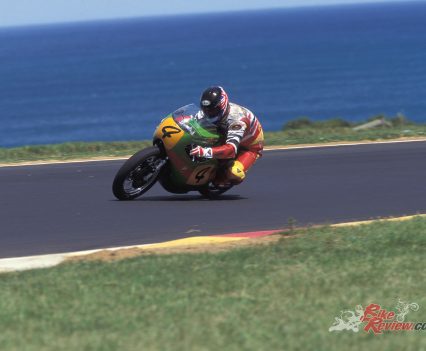

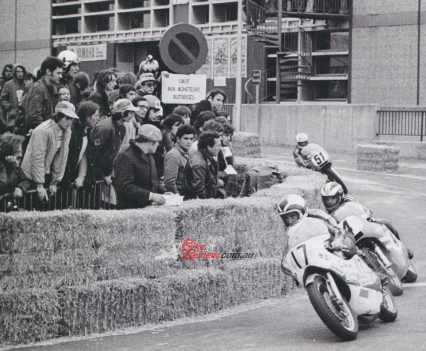

But the galloping growth of Post-Classic racing Down Under encouraged him to dig it out of retirement, re-sleeve the cylinder and persuade the Wiseco importer to source him some pistons. In 1994, the H1R took to the race track for the first time in eight years with resounding success: first Brendan rode it to the a pair of 500cc race wins in the Island Classic at Philip Island, then he repeated the success at the Australian Post-Classic championships at the Eastern Creek GP circuit later in the year. In the quarter-century since then the ex-Molloy H1R has been a regular visitor to Victory Lane Down Under.

“To find a period racer of any kind in such original, authentic condition, yet still capable of winning races is a rare event, but all the more so when it’s one of the early customer GP two-stroke.”

To find a period racer of any kind in such original, authentic condition, yet still capable of winning races is a rare event, but all the more so when it’s one of the early customer GP two-strokes, which generally seem to have been modified more than the equivalent Manx Norton or Aermacchi.

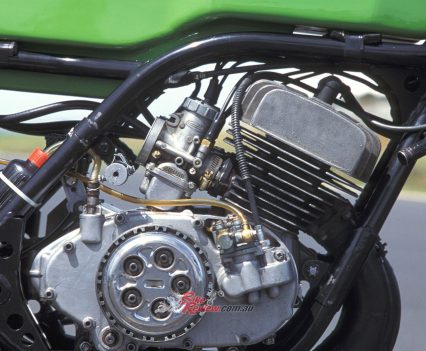

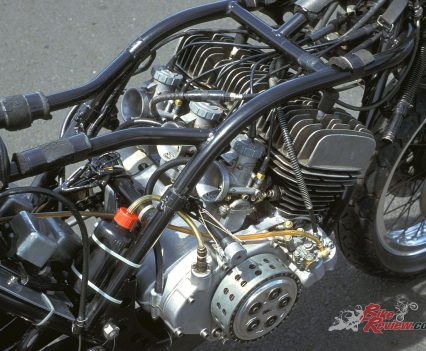

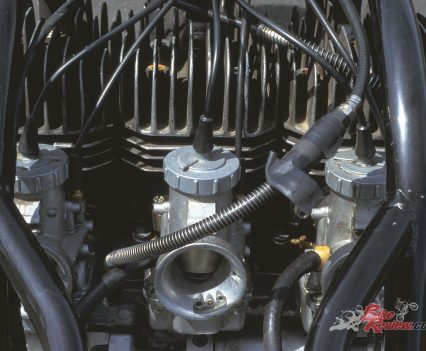

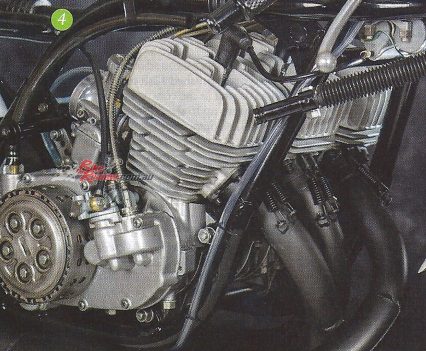

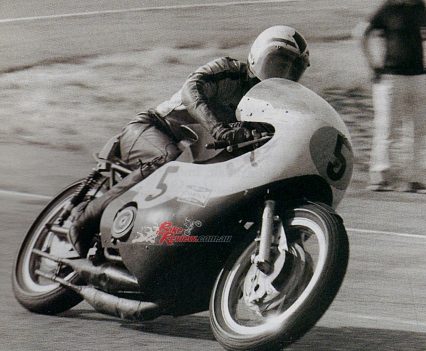

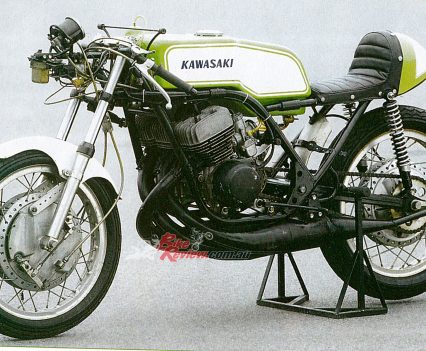

But Brendan’s H1R is essentially exactly the same as when Ginger Molloy last rode it, complete with the H1R-A power-up kit made available for 1971, with different exhausts from the crossover type originally fitted to save bulk. Together with altered port timing and other minor changes, this bumped power output up to 80hp@9,500rpm, but Ginger Molloy already had the Bultaco factory spend a day re-porting each cylinder, says Brendan, so the exhausts were the main improvement on his bike.

The H1R-A also had crank mods which saw roller bearings with a brass cage fitting on one side, but with Yamaha rods fitted and special crankpins with smaller Yamaha needle roller bearings which don¹t generate so much heat, so last longer. Apart from the inevitable broken cylinder studs and assorted clutch problems, Brendan says the bike has been very reliable during the time he’s raced it, thanks to the modern race pistons and Bel-Ray oil, as well as conservative jetting. Still, it didn’t persuade me not to leave my clutch hand on the lever at all times when I rode it, though – just in case!

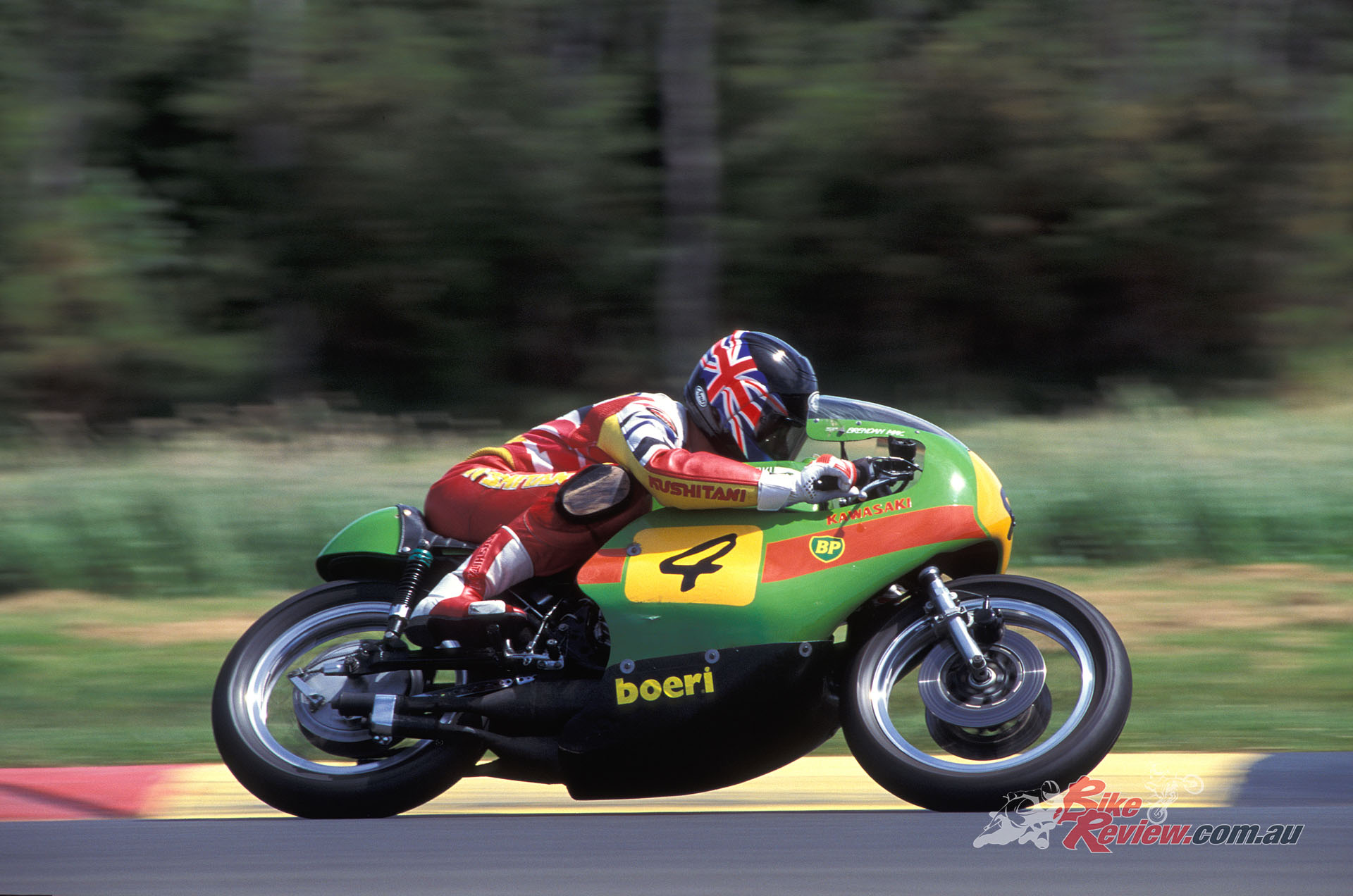

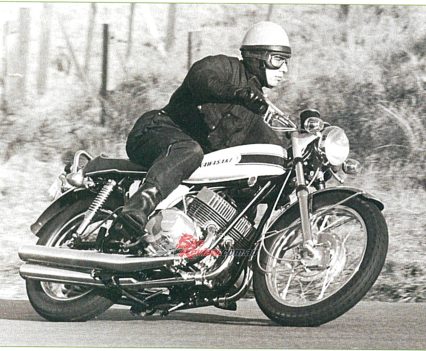

That’s when I wasn’t holding on tight to stop getting left behind when the power suddenly came in strongly, though – because make no mistake, riding this bike is an acquired skill which 15 laps of the Phillip Island GP circuit saw me only partially trained in. The first trick is to start it: the clutch action is very stiff, so it’s quite hard to catch the engine as it fires and a real knack is needed to match throttle opening to engine speed, making the push-start GPs of the era a bit of a challenge that presumably came with practice. Even once you¹ve got it fired up (OK, I admit it: I had to get Brendan to start it for me!), getting it off the mark is hard, too: more practice needed, AC!

“Riding this bike is an acquired skill which 15 laps of the Phillip Island GP circuit saw me only partially trained in…”

The problem was that a career of test riding modern GP two-strokes had left me unprepared for the degree of brutality it was necessary to inflict on the Kawasaki’s clutch in order to wind the revs up high and made the motor sing.

“A career of test riding modern GP two-strokes had left me unprepared for the degree of brutality it was necessary to inflict on the Kawasaki’s clutch in order to wind the revs up high and made the motor sing.”

Forget about the later GP two-strokes with their mile-wide powerbands and more gradual delivery obtained by electronic trickery like powervalves and traction control: this is a bike from the days when a clutch lever was your passport to race-winning horsepower, delivered right now rather than later.

There’s no power at all below 7,000rpm on the Molloy Kawasaki with its H1R-A pipes, and to make it really motor you have to get it revving at 8,000rpm or higher. But when the tacho needle hits that mark on the dial, you better be holding on tight: suddenly, the Kawa will lunge forward as the power comes in strong, and if you happen to be cranked over at the time, exiting one of Phillip Island’s slower turns, be prepared for the rear Avon tyre to go walkabout, chopping across the tarmac as it scrabbles for grip and your heart-rate goes ballistic.

If you happened to have inflicted this excitement on yourself by clutching the engine out of a slow turn, it seems doubly daft: that’s when you learn to pick the Kawasaki upright before you gas it hard or clutch it – and try not to let the revs fall out of the powerband, ever. Since the engine is redlined at ten grand and you have only a five-speed gear ‘box to play with, this is easier said than done – but a pit stop for advice brought reassurance from Brendan.

“The 10,000 rpm redline is only for the standard H1R,” he said, “whereas this uprated engine has less power low down, but is safe to quite a bit higher. Just let it go!” OK, boss – I did, and now I can believe that amazing 276km/h Bathurst trap speed, because a) it carburates best at high revs, and changing up at 10,500-plus allows you to keep above the magic eight-grand barrier, and b) the Kawasaki is extremely quick by any standards, and especially those of 1970. I mean, seriously fast – swapping a Manx Norton for this must have been like flying Concorde after a turbo-prop. The future beckoned, and it was named Kawasaki.

“The Kawasaki is extremely quick by any standards, and especially in 1970. I mean, seriously fast – swapping a Manx Norton for this must have been like flying Concorde after a turbo-prop.”

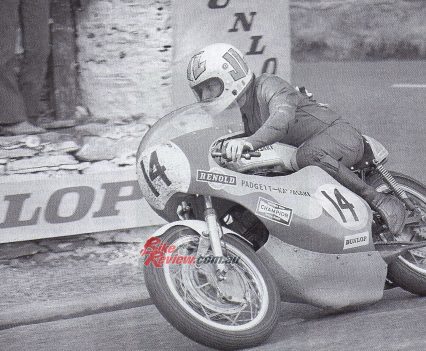

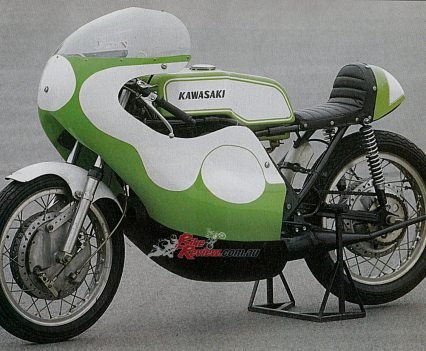

The riding position reminded me more of a 125 than a 500, with a skinny upper fairing and steeply dropped bars that didn’t give much leverage for muscling the H1R round turns, but presumably help present a relatively slim profile as well as encouraging you to tuck well away behind the low screen.

“The riding position reminded me more of a 125 than a 500, with a skinny upper fairing and steeply dropped bars that didn’t give much leverage for muscling the H1R round turns.”

The bottom part of the fairing is relatively bulbous, thanks to the wide crank and bulky exhausts, but it doesn’t ground easily and the handling is actually pretty good even over bumps, within the context of 50 years ago. The high centre of gravity made it awkward in slow turns, where it tipped into corners rather suddenly despite the kicked-out head angle, and the bulk of the big fuel tank made it feel meaty and butch to ride.

It skipped about over bumps – like the one on the inside of Lukey Heights at Phillip Island – but any period twin-shock bike will do this, and the Kawasaki seemed relatively controllable, at least with the light fuel load I was riding with. Brendan was unable to get the original Kawasaki shocks rebuilt, so has fitted Konis which are probably more compliant as well as being 10mm longer, thus increasing rear ride height by that amount.

Cathcart said the Koni’s seemed to improve some of the handling but the bike was still a handful to ride…

This might account for the fact that the H1R didn’t have the ass-down feel that most period two-strokes of the 1970s have, as well as for its good ground clearance, but it didn’t cure the noticeable power understeer that was the main feature of the bike’s handling. It pushed the front wheel and headed for the hills each time I got hard on the pipe in the middle of a turn, and needed a good tug to pull it back on line. The fact that the front WM2 rim was surely over-tyred with the 110/80-18 Bridgestone fitted mightn’t have helped, especially with the rather flimsy forks which were pretty hopeless at coping with bumps cranked over on the power, chattering the front tyre quite dramatically.

Answer: either hold on tight and grip that big fuel tank with your elbows and knees while keeping the throttle wound on, or else plot a smoother course and try to keep the bike more upright entering a turn, braking hard before you peel off into it, then accelerating hard into the apex like you do in a racing car. Late braking, early acceleration and a short transition time are the keys to riding a bike like this fast, and the potent engine rewards that approach. Just make sure you brake hard into the peel-off point, with the clutch in and changing down two or three gears at a time – but bottom is very low, and I couldn’t grab it till the last moment just as I was ready to get on the gas again.

Taking MG or Siberia was all a question of timing – that and judgement: the stainless steel Honda CB500 discs Ginger Molloy fitted to the bike had just as little bite as the ones on my XR750-TT Harley road racer I used to own and race – which is why I fitted a Fontana drum front brake to it. The discs may be lighter than the heavy original Japanese drum brake, but they don’t make the bike stop so well, and Ginger regretted making the swap, says Brendan. I know why!

But I’m sure Ginger didn’t regret racing the Kawasaki, and becoming the man who ushered the modern era of machine development into the Grand Prix arena. Thanks to Brendan and Brad May, a valuable piece of two-wheeled history can be seen in action today, still preserved almost exactly as it was when it gave Agostini a wake-up call more exactly five decades ago this year. History lives again!

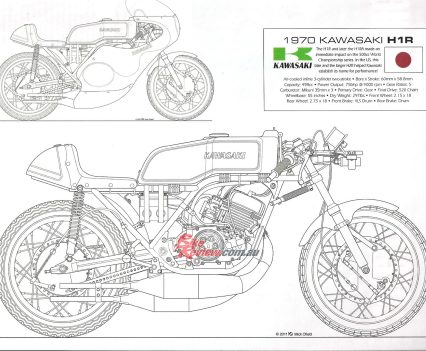

1970 Ginger Molloy Kawasaki H1R Specifiations

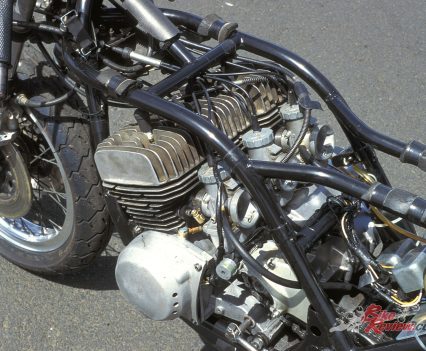

ENGINE: Air-cooled transverse in-line three-cylinder piston-port two-stroke with separate oil injection to 120-degree crankshaft, 498cc, 60mm x 58.8mm bore & stroke, Kröber CDI, 3 x 35mm Mikuni VM35SC, 5-speed gearbox with multiplate dry clutch

CHASSIS: Tubular steel duplex cradle, 35mm Kawasaki telescopic forks (f) Tubular steel swingarm with twin Koni shocks (r) 2 x 260mm Honda stainless steel discs with two-piston Honda calipers (f) Kawasaki 220 mm twin leading-shoe drum. (R) 110/80-18 Bridgestone Spitfire on WM2/1.85in Borrani wire-spoked rim (F) 130/70-18 Avon AM23 on WM3/2.15in Borrani wire-spoked rim (r). 1390mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 82hp@9,500rpm (as delivered, 75@9,000rpm), 277km/h (Bathurst 1973), 134kg dry.

Owner: Brendan and Brad May, Melbourne, Australia.

1970 Ginger Molloy Kawasaki H1R Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.