Alan Cathcart looks deep into the development of arguably the most important Yamaha YZF-M1 MotoGP of all time, the 2004 Valentino Rossi winner...

Yamaha’s first YZF-M1 MotoGP racer produced back in 2002 had measured 920cc, because the company’s original concept for the bike was to make it narrow and small, with a good power to weight ratio achieved through a compact in-line four-cylinder motor.

Yamaha were using technology they were familiar with, resulting in a lightweight chassis, with cylinders inclined forward by 15 degrees for better installation and weight balance. But after the success of Honda’s RC211V disproved Yamaha’s original contention that the output of a full-capacity MotoGP engine would be unusable, the engine was brought up to a full 990cc in the middle of 2002, by increasing both bore and stroke from before. And for 2003 the carburettors originally fitted were jettisoned in favour of fuel injection, primarily for superior fuel efficiency since consumption was becoming more of an issue.

16-valve Growler format, with firing pulses on two cylinders closed up to around 60 degrees of crankshaft rotation…

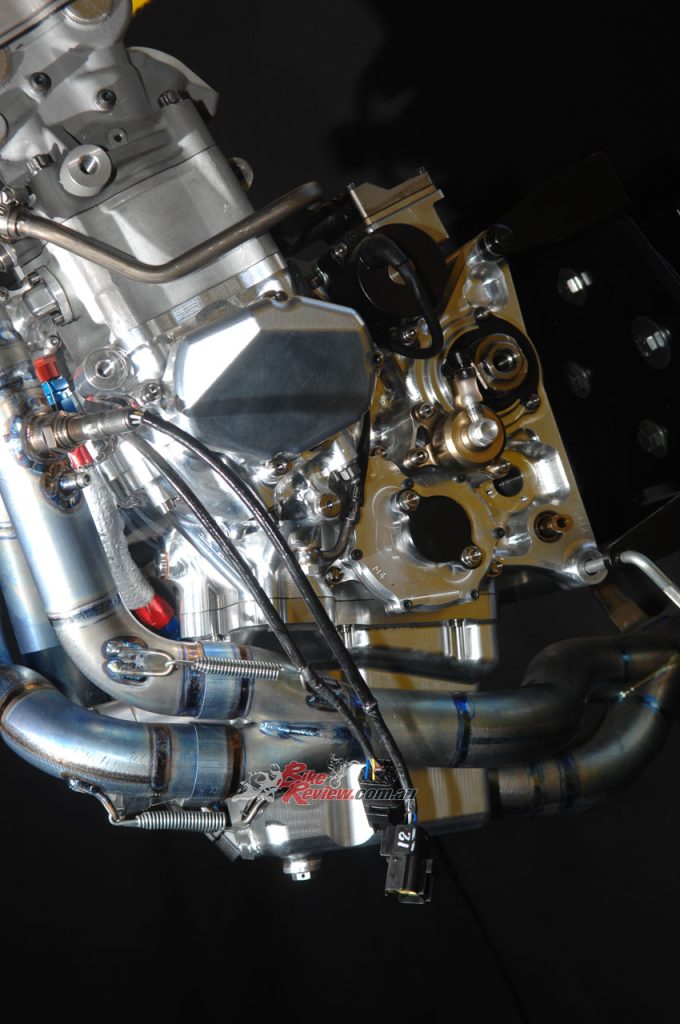

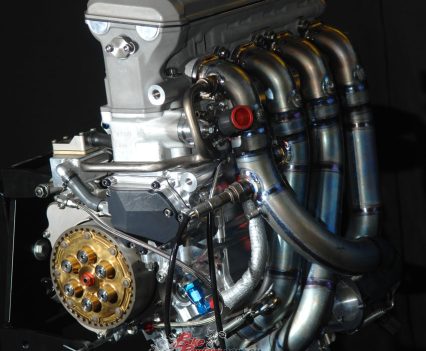

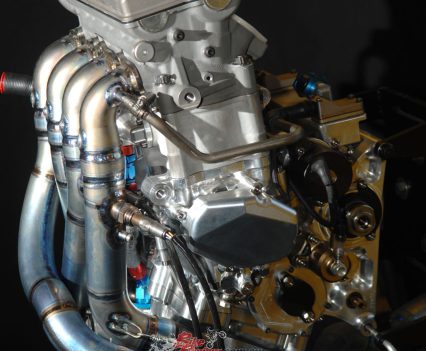

Originally, flat-slide throttle bodies were employed, with Yamaha’s own engine management ECU, but with the two injectors per cylinder coming from Marelli, plus some other parts. From Le Mans in 2004, a full Magneti Marelli EFI system with a smaller, lighter Formula 1-derived ECU was fitted to Rossi’s YZF-M1 for the first time, having been first developed on Abe’s and Melandri’s Tech-3 bikes.

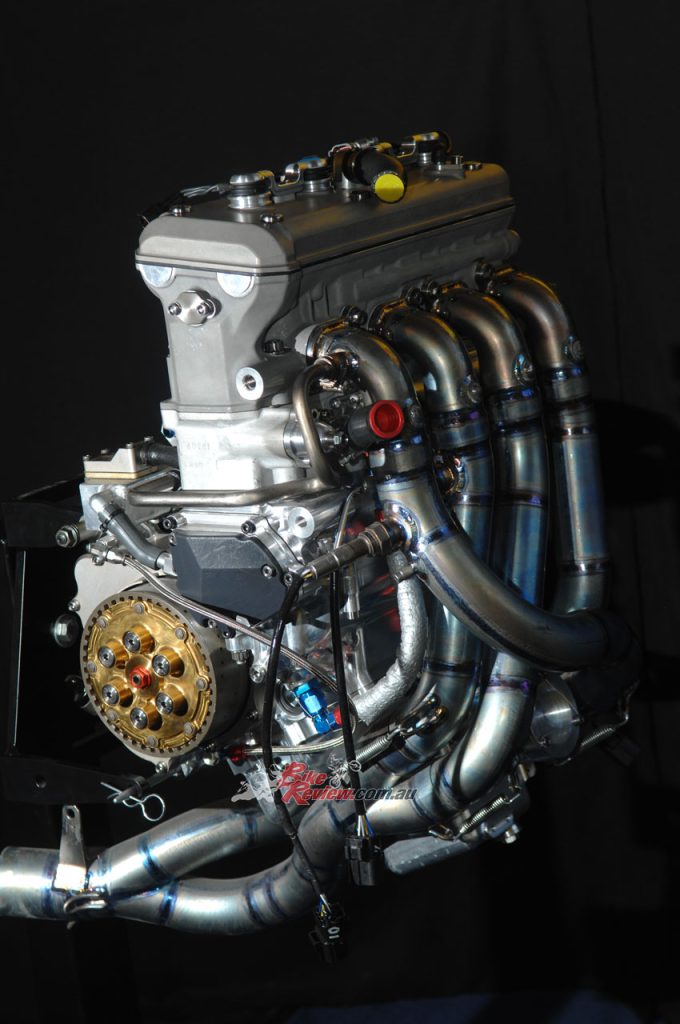

In its 2004 16-valve Growler format, with firing pulses on two cylinders closed up to around 60 degrees of crankshaft rotation, followed by a space of around 300 degrees before the next pair fired close together, in order to improve traction and (theoretically) tyre life, the YZF-R1 motor was still further unusual in running backwards as before, but with the intermediate shaft located between the crankshaft and clutch to reverse the direction of rotation now conveniently available to be fitted with balance weights in order to act as a counterbalancer, thus eliminating undue vibration resulting from the uneven firing order.

Check out Alan’s full test ride on the 2004 Yamaha YZF-M1 here…

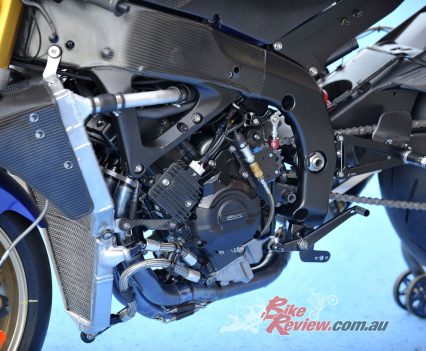

The one-piece crankshaft was still machined from solid, and drove a short chain directly to an intermediate gear, which then actuated the double overhead camshafts. The titanium valves each had two springs, and employed bucket-and-shim adjustment, while as before, the ultra-slipper two-ring pistons were mounted on titanium conrods. The Termignoni 4-2-1 titanium exhaust was one of the few on the MotoGP grid to still be fitted with a silencer, a weight penalty which Yamaha could afford since, as before, the YZF-M1 scaled in right on the MotoGP weight limit, especially after this was raised to 148kg for 2004.

The YZF-M1 was still a short-stroke design, though not extremely so – only a little more heavily oversquare than Yamaha’s R7 Superbike, for example. In 2003, engine output was 240bhp at 15,350rpm measured at the crankshaft, 25bhp more than the previous year’s original smaller engine running on carburettors, to which Yamaha claimed to have added an extra 10bhp for 2004, to flirt with the 250bhp barrier.

Yet, just as in 2021 the World champion YZF-M1 was still down on outright power compared to the Ducati and Honda, albeit still very light in weighing only 50kg, so 14kg/30 per cent lighter than the R1 Superbike engine of the same capacity (and even 8kg less than an R6 Supersport 600 motor!). And, at 350mm wide the M1 was 20mm narrower than the R1 (and 40mm slimmer than the R6), as well as more compact – it was 1 per cent shorter in length and 5 per cent lower in height than the R1.

This originally allowed Yamaha to design a smaller, lighter Deltabox chassis, and while for 2003 this had 11 per cent more torsional rigidity than the first year’s frame, and 14 per cent pitching stiffness, while keeping lateral rigidity unchanged, as Furusawa-san revealed the latter was considerably decreased for 2004, to redress Valentino’s complaint that the bike was too stiff.

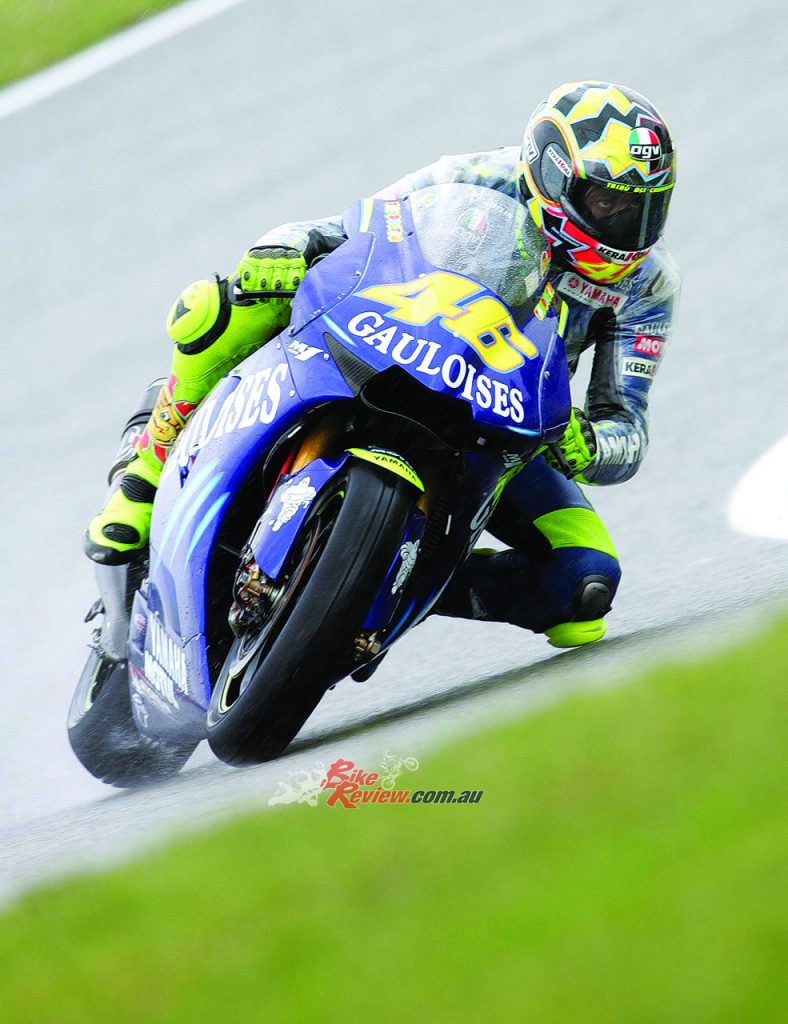

The YZF-M1 also suffered badly from rear wheel chatter in 2003, a problem which he claimed had been cured via suspension settings – but despite the supposed benefits of the Growler motor, the Yamaha remained harder on its rear tyre than its Honda rivals, and usually couldn’t run as soft and thus as grippy a choice for race distance as they could.

The prototype of the 2004 chassis first appeared at Valencia in 2003, with new upper engine mounts on the base of the cylinder block, rather than the cylinder head, and a reversed fully-machined swingarm with bracing underneath rather than above, to lower the cee of gee. But the bike was nevertheless raised 25mm overall for Rossi by the time he raced it for the first time in Welkom, and had also been lengthened by 20mm.

Continued experimentation at each race – and especially for the wet, where handling continued to be a problem – led to a new chassis appearing at Assen which was gradually refined during the remainder of the season, to enhance grip and traction while still permitting high corner speed and a tight turn angle.

The six-speed gearbox was naturally an extractable cassette-type transmission, mated to a dry ramp-style slipper clutch whose conventional anti-lock function under reverse torque loads during engine braking was further supplemented by an electric motor which operated a so-called ‘kicker’ system introduced for 2003, properly known as an Idle Control System/ICS.

This was a quite simple electronic solution, whereby the throttle twistgrip as usual controlled the opening of the four throttle bodies, but with two of these influenced by the ICS. Even after the rider had shut the throttle under braking, this adjusted the opening based on the input of the ECU during deceleration, which monitored wheel speed front and rear, throttle opening, engine rpm, gear selected, and braking pressure, to raise the idle speed as appropriate to prevent the rear wheel chattering.

This was a quite simple electronic solution, whereby the throttle twistgrip as usual controlled the opening of the four throttle bodies, but with two of these influenced by the ICS. Even after the rider had shut the throttle under braking, this adjusted the opening based on the input of the ECU during deceleration, which monitored wheel speed front and rear, throttle opening, engine rpm, gear selected, and braking pressure, to raise the idle speed as appropriate to prevent the rear wheel chattering.

This was a quite simple electronic solution, whereby the throttle twistgrip as usual controlled the opening of the four throttle bodies, but with two of these influenced by the ICS…

For 2004, what was previously a setup using preset engine mapping became a real-time system, which factored in tyre, weather and track conditions into the ICS kicker response. But the rider had to still use the clutch to backshift, because operating this triggered the system, which had also been considerably modified electronically from 2003, to give more feel. And further electronic control was supplied via traction control, which Yamaha employed off the start line, then again in the race if the rear tyre lost grip, when the rider could select a different map with less aggressive characteristics via a switch on the left handlebar.

For optimum cooling, they used MB Motorsports radiators manufactured in Italy, which were very light and well-made.

Yamaha’s pressurised carbon airbox on the YZF-M1 was now over 20 per cent larger than when they began MotoGP, and was fed by the biggest intake duct on the MotoGP grid, positioned beneath the nose of the fairing to deliver high-pressure ram air without sacrificing the engine’s cooling efficiency – it was so big, the bottom lip of the carbon-fibre intake mouth had to be flexible so as to give way when the front mudguard touched it under heavy braking!

Yamaha’s pressurised carbon airbox on the YZF-M1 was now over 20 per cent larger than when they began MotoGP, and was fed by the biggest intake duct on the MotoGP grid…

For optimum cooling, Yamaha used big MB Motorsports radiators manufactured in Italy, which were very light and well-made. This increased airbox capacity was a direct result of the low-slung fuel tank, which carried most of its 24-litre capacity low in the chassis, to provide space for the larger airbox. But this also had extra benefits, by lowering the centre of gravity, and reducing the pitching effect experienced under heavy braking with a full fuel load.

Yamaha’s aim in developing the YZF-M1 with its transverse in-line motor was to concentrate mass and reduce polar moment as much as possible, to achieve better balance in handling aimed at maximising corner speed, delivering more neutral handling, and improving traction so as to give the riders confidence to accelerate earlier and brake deeper into the turns, using the bigger footprint of Michelin’s new 16.5-inch front tyre introduced that season to optimum effect. Weight distribution was now 56/44 per cent static, but more importantly an even 50/50 split with a rider of Valentino’s weight in the hot seat – the optimum target to achieve the above objectives.

“Öhlins’ new TT25 dual-cartridge 42mm inverted forks were used all season, while Brembo radial calipers gripped either 305mm or 320mm carbon discs”.

Öhlins’ new TT25 dual-cartridge 42mm inverted forks were used all season, while Brembo radial calipers gripped either 305mm or 320mm carbon discs, depending on the circuit – and it’s worth noting that Valentino sometimes ran shrouds on these to keep up disc temperature, perhaps an issue because he didn’t brake as hard as his Honda-mounted rivals, using more turn speed to help redress the top speed and outright power handicap the Yamaha suffered at present. Rossi’s Yamaha was 12th fastest through the speed traps down the Catalunya circuit’s long front straight, yet he still had the quickest lap time…..

The man who transplanted Yamaha’s MotoGP race operation into title-winning territory instead of being best of the rest, is its (then) 53-year old new race boss Masao Furusawa, a 31-year company veteran who since joining Yamaha in 1973, has an impressive and varied history of successful troubleshooting behind him, as well as some notable design highlights on his C.V. – including designing the engine of the legendary RD350LC…

Asking the man responsible for creating Elsie Yamaha to take charge of the company’s ailing road race operation (which, unlike Honda, was at that stage contesting only the MotoGP class, not 125/250 GP, nor Superbike as in 2005) meant he took charge of Yamaha’s Technology Research Division under which racing is grouped, on June 1st, 2003 – but though this was Furusawa-san’s first involvement in bike racing, it wasn’t the first time he’d headed up one of Yamaha’s competition departments, having been given responsibility in 1992 for snowmobile operations.

an impressive and varied history of successful troubleshooting behind him, as well as some notable design highlights on his C.V. – including designing the engine of the legendary RD350LC…

“This was a nightmare for Yamaha,” he recalls with a wry smile. “We hadn’t been involved in snowmobile racing for 18 years – but in my first year, we won the championship with rider no.46, an American named Chris Vincent! So, no.46 is a very lucky number for me, and when I learnt that Valentino Rossi will race for Yamaha with this number in 2004, I was sure this is a good sign!”

Furusawa-San is royalty for every red-blooded motorcyclist on the planet, not only for the first title winning YZF-R1M, but for the mighty RD LC engine! What a legend!

The chance to talk with Furusawa-san – who, amazingly, had never seen a motorcycle road race until he attended the 2003 French GP at Le Mans – at the Valencia test, uncovered the story behind Yamaha return to title-winning triumph for the first time in 12 years.

AC: Furusawa-san, after you took charge in June last year, what were your first steps to turn the M1 race effort around?

MF: “When I joined Yamaha’s race division, the first thing I did was just to watch the YZF-M1 in action on the racetrack, observing how it’s braking, turning and accelerating. I saw from this that some things were wrong – so I made a long list of many, many things to be fixed. But time was so limited before the 2004 season, I put some things at the top of the list, as a priority – and the most important of these was the character of the YZF-M1 engine. Power delivery is more important than power itself, but last year I didn’t have enough time to address this properly in the middle of the season, so to begin with, I just increased horsepower. Finally, we had a very high maximum speed, and also improved our performance in qualifying – but in the actual race, we lost. I wondered, what is so wrong for Yamaha, that we cannot win races with this bike? – and of course I changed suspension, geometry and engine management to try to improve this, through my engineering staff who are so experienced and have worked so many years for Yamaha. But without success – so, I decided we must have an entirely new concept for the YZF-M1 engine in 2004…

“However, while it’s not so difficult to modify the chassis, altering the engine is very much more time-consuming. The more I analysed the inside of the existing YZF-M1 motor, the more I decided our staff must design a new engine – but while in theory I was convinced this new engine would work very well, some staff in our company were not so sure. So, to verify this, we created a prototype and tested it on Christmas Day last year for the first time at Fukuroi, the Yamaha test circuit – and the rider was so impressed. He said, “Wow! Big jump!” So this gave us all much confidence for the coming season – especially now we have Valentino Rossi riding for us!

“But first, I decided I must allow him to choose which kind of engine he wants to ride. So when he tested for Yamaha at Sepang in January, I prepared four different engines for him to test, each with a different character, and each with appropriate chassis type, hoping that he would choose the one we were working on. But first, I let him ride the existing 2003-model YZF-M1. He said, “Hmm – very aggressive – but I can manage this, with some changes.” I was quite surprised to hear this – but I did not say anything till he tried the other choices. Then at the end, I let him ride the new prototype machine, knowing that at this stage it didn’t have so much power, because it was still so new – about 10 bhp less than the existing 2003 model. Immediately, Valentino says ‘This one is the best – but I need more power!” I was very happy, of course – but it was thanks to him that Yamaha engineering staff could work in the correct direction for this season’s championship. He is a genius – his feedback is so precise and he is so quick to assess changes, that we can speed up our development time quickly”

The success of the M1 can’t be boiled down to one person, but a combination of people with gifted mechanical brains.

AC: Still, with less than three months before the first race of the season, in South Africa, how difficult was it to build and develop what was really an all-new bike in that short time?

MF: “Because Valentino is so quick to learn and suggest improvements, it was not so difficult – and of course for Yamaha engineers it is a pleasure to work hard for someone who is so responsive to their efforts. Of course, the first job was to modify the engine to get at least the same amount of power as last year’s bike, which we succeeded in doing quite quickly – and in testing Valentino consistently improved his lap times, so I began to hope we could win the first time together in South Africa. But when he did so, against so many Honda riders, it was simply fantastic – maybe the most important race win ever for Yamaha, in all the many years we raced in Grand Prix. Of course, we won many races and world championships before – but to come from so far down to win again, with a completely new bike and team of mechanics and especially rider, was a very great moment for everyone in Yamaha. I must admit I felt very great satisfaction after this victory – but also concern, because now we must work very hard to maintain momentum and repeat this success in every race to win the world championship. And I knew Honda would work very hard indeed to prevent this happening – so our big concentration was to get more power, without sacrificing usable power delivery”.

AC: The history books show that Yamaha’s efforts were successful. How much more power did you manage to find between that first race in Welkom and winning the title in Australia?

MF: “We succeeded in finding 20 bhp more from our four-valve engine between the start of the season and the end – but while this makes it more powerful than the old-model YZF-M1 with five valves per cylinder, unfortunately it’s still not as much as Ducati or Honda. But sooner or later, we will manage this – our development path is really promising, and already we have the 2005 motorcycle ready for testing here at Valencia tomorrow. So we are well advanced”!

AC: So now let’s look at the 2004 world title-winning engine. Please explain the differences to the 2003 bike’d engine.

MF: “Five-valve and four-valve engines each have their own advantages, so it’s not a question of one being better than the other. It depends on your objectives for the engine character. Five-valve is better for airflow, especially at low rpm where there is stronger intake contributing to better acceleration – but at really high rpm, like in MotoGP, the advantage of the five-valve system is not so much, even with the improved gas mixture benefits it brings.

Five-valve gives more aggressive throttle response to the rider, so the street customer can have more fun and get better wheelies – but for racing, this is not needed: we must have more usable power delivery. So this is why I proposed a four-valve design, which Valentino agreed with – it has more sweet, more gentle power delivery, which is why we use this for the FJR1300 touring bike and even for the R6 Supersports 600, where we have very high revs but the engine must be usable and not too aggressive, while still performing. But, for the TRX850 twin-cylinder sports bike (arguably Yamaha’s first Growler motor, with its closed-up 90/270-degree firing order! – AC), we used a five-valve concept, because we wanted stronger engine response, and the twin-cylinder engine character takes care of rideability.

“So we can design the engine according to the purpose, and originally we thought for MotoGP that five-valve is best – but after I found that the key to success is the power delivery, we went to a four-valve system. This makes the bike more manageable, and allows the rider to lap faster provided you can meet the same peak power target as a five-valve design. And, as I just told you, we managed to do this with our new four-valve engine, which for improved combustion and breathing through bigger valves, has a relatively flat valve angle that also helps make the engine more compact, because it allows the camshafts to be closer together.

“Power is easy to understand – it’s like a kind of medicine, and sometimes if you take too much of it, it can hurt you almost as much as the illness you’re trying to cure! So, this season I introduced one engine with more power, but the delivery to the rider tuned out not so good, so I withdrew it. But still we need more power for 2005 – and I hope our new engine delivers it in a good way”.

AC: How about the Big Bang engine format also introduced for last season, which led to the bike’s distinctive growling exhaust note? Was that one of the four kinds of engine Valentino tried at the start of the year?

MF: “That’s not the right term to describe it – I don’t believe in the Big Bang theory for MotoGP machines, where you have two pairs of cylinder firing together. This has instead an alternative individual firing order compared to a conventional four-cylinder in-line engine, and in fact it was this engine we first tested at Fukuroi last Christmas, still in five-valve form. Then later I added the four-valve concept, not the other way around. But we still didn’t finish yet. This engine that Valentino won the World Championship with at Phillip Island, and used again to win here at Valencia, has one of the best crankshaft layouts which we used for racing all season long, but we are still working on improving it with small differences to the firing order, which we have been continually testing all year on the racetrack, and also on the computer. We will go on doing so”.

The M1 was amazing under the brakes, it wasn’t just about the Brembo’s, engine braking had some improvement.

AC: One big improvement over 2003 is the YZF-M1’s behaviour under engine braking. How did you achieve this?

MF: “We still retain a conventional ramp-type slipper clutch, though not relying entirely on this but with some mechanical improvement. But last year we had much more electronic control, whereas this season we had more of an old-fashioned mechanical system combined with some electronic support, only much reduced. The most important thing is rider feeling, and we realised that before we eliminated this too much”.

The simple LCD dash would’ve been big tech in 2004. Imagine the whole dash flashing in your face as you bounce of the rev limiter.

AC: Last season, another reason for the YZF-M1’s more aggressive power delivery besides five-valve cylinder head design, were the flat-slide guillotine throttles you fitted – are these still retained with the four-valve engine. And do you have bigger throttle bodies than before to go with the four-valve layout?

MF: “Yes, we do – but don’t assume intake total valve area is bigger with two intake valves on four-valve system, compared to three intakes in five-valve layout. Sometimes bigger valves are better for total gas mixture flow, but smaller ones improve the speed of the mixture, because you are squeezing it through a narrower-diameter space. We made many experiments on this, and are learning all the time how this affects engine character. And no, we don’t use guillotine throttles any more, but instead twin-butterfly design which gives friendlier power delivery”.

AC: Did you have to make big changes to the chassis, to maximise benefits from the new engine?

MF: “Sure. Exactly one year ago here at Valencia after the GP, we introduced a new chassis which Carlos Checa tested. It was not so different than before, but it showed the direction we needed to go in. We decreased the lateral stiffness quite considerably, while increasing torsional and vertical stiffness just a little. This concept turned out to be a big improvement, which we developed quite considerably with Valentino during this season. We followed the same path with swingarm design, except that this year we put bracing underneath the structure rather than on top, to lower the centre of gravity as well as reduce lateral stiffness. However, when he first tested the 2003 YZF-M1 at Sepang, Valentino said it was too low, so we must raise it for him at both ends. This change helped counted some disadvantages of this for him”.

AC: Still, after riding it, it seems the Yamaha’s riding position is still quite low. Does the low cee of gee improve stability over bumps, as well as aid steering?

MF: “No, I don’t think so. From the standpoint of agility, we need a shorter wheelbase, and Kawasaki and Yamaha are shortest, because of the advantages of the in-line engine layout. Of course, this can also lead to stability problems – but I think we learnt how to avoid this by making the wheelbase just a little longer than last year, just 20mm on the whole chassis, not only the swingarm. But we also had a little more weight on the front wheel than last year – instead of 55% on the 2003-model YZF-M1, now we have around 56-57 per cent, which together with the unchanged engine character, also helps reduce wheelies. But most important is the combined cee of gee location of whole bike package and rider, which in an ideal situation is 50/50. You can imagine in a corner, off-throttle, if the front is sagging or rear is too low, it’s really hard to come out of the turn properly – so 50/50 is ideal. But, this is not all – we need a dynamic weight transfer to improve traction when the bike is accelerating, or grip when braking – and on last year’s bike it was impossible to achieve this correctly, because of the engine character. This year, we improved this very much – but it’s still not perfect, so we will continue to work in this area. We must use positive benefits of weight transfer to the maximum – riders always want more traction, so this is one way we can achieve this”!