The story behind the creation of the original Z1 is legend in itself, and a closely guarded secret at the time... Story: Mick Withers, Norimasa Tada Photography: Kawasaki, N Tada, KMA, Keith Muir

‘New York Steak’ – Looking at the thousands of different motorcycle models released since Gottlieb Daimler went for a ride in 1885, it is fair to say that few models have created anywhere near the cult following and legendary status of the Kawasaki Z1.

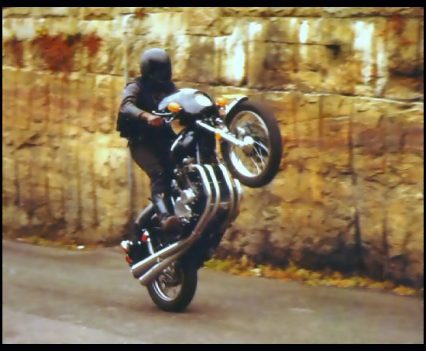

Long before the Internet arrived to allow anyone to be an instant expert, there were myths and rumours flying around the motorcycle world about the pre-production Z1s and their capabilities. If you believed all that you heard, those pre-1972 bikes were able to run 10-second quarter mile ETs and top 150mph before Kawasaki engineers detuned them.

When I wandered into the motorcycle scene in the early 80s, experts were to be found in every gathering of riders. Each group had its own specialist, some of whom actually rode a Z1 or one of the later derivatives. They would wink and nod knowingly while revealing the secrets such as which camshafts were the best or why you should run the 26mm carbs from the 1976 A4. Dare to question their knowledge at your own peril!

Over the ensuing years, much more credible information became available. Prolific English author Roy Bacon wrote a book titled ‘Kawasaki – Sunrise to Z1’ that was released in 1984. It set a benchmark and contained information that had previously only existed behind closed doors. My copy was purchased soon after release and still holds a place of honour in the home library.

As well as allowing anyone to make claims, the internet has allowed the sharing of knowledge and information in a manner that sees likeminded folk come together in the same forum or social media page. True Z1 fans can find an incredible array of factual information from very credible sources.

We now know that Kawasaki instructed a team of engineers led by Gyoichi ‘Ben’ Inamura to produce a large capacity, four-cylinder four-stroke motorcycle with a capacity of 750cc. Codenamed N600, this brief was issued in 1967 following studies of the American motorcycle market and was labelled New York Steak. As a company, Kawasaki was very keen to be the first Japanese company to bring such a motorcycle to market.

The Tokyo Motorcycle Show in October 1968 was the venue for Honda’s release of the CB750-4 and that sent the Kawasaki crew into shock. A new brief was issued in 1969 calling for a capacity increase to 900cc as well as an increase in horsepower over the Honda. Production was planned to start in 1972 allowing the H2 750 Mach III and IV models to have a good run before the release of the Super Four.

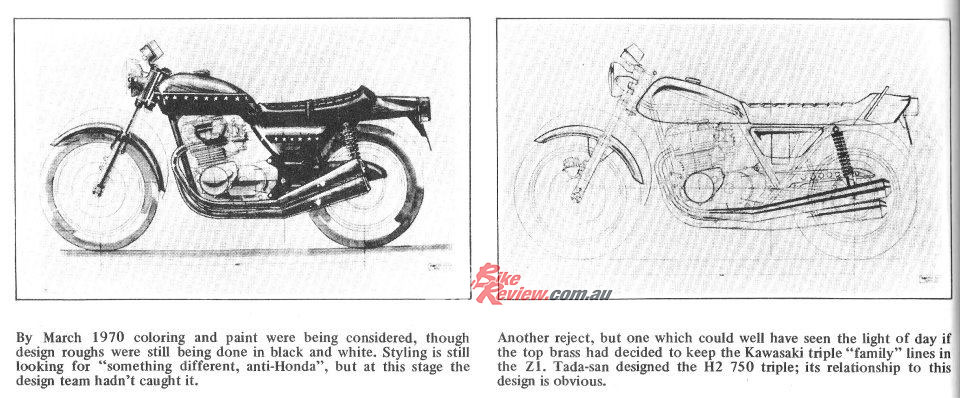

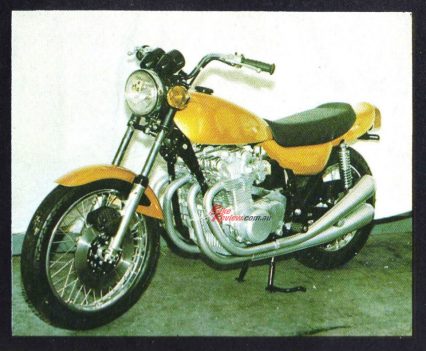

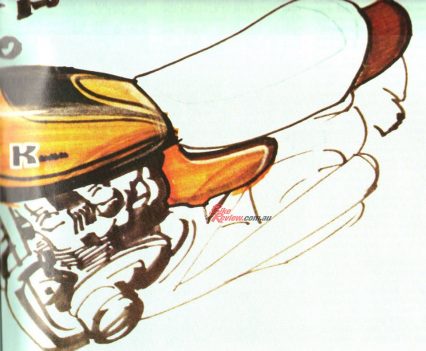

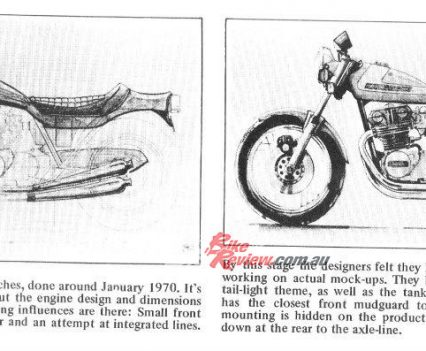

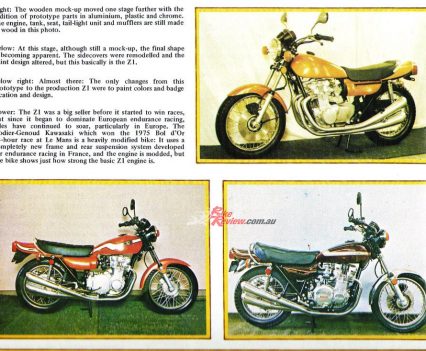

Early in 1970, styling sketches were produced giving the image of a lightweight sprinter displaying what Norimasa Tada described as ‘The Three S styling concept: Slim, sleek and sexy.’ Following this, a trial model was constructed with wooden frame and clay for the bodywork. Noboru Fukui was working at Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) on the same floor as the design team and recalls the use of a hairdryer to dry the clay!

In the middle of 1970, a project team was formed with engine and chassis specialists. The N600 crew had already completed much of the work on the engine. Norimasa ‘Ken’ Tada reveals much of what he knows in the sidebar.

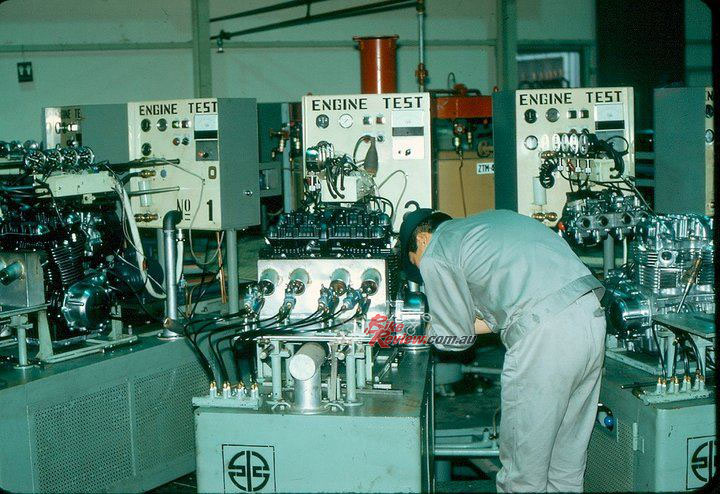

Work on the 903cc prototype progressed quickly and the first V1 was run at the Yatabe test circuit in 1971. These bikes were so-called due to their engine and frame numbers starting with the V1 prefix rather than the Z1 of the later production bikes.

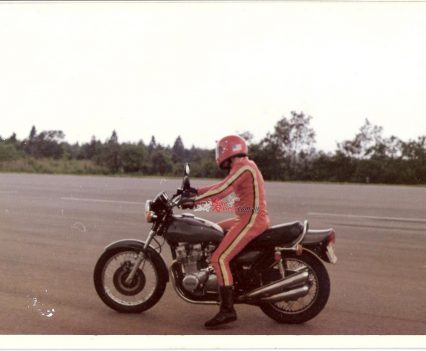

Bryon Farnsworth was recruited and travelled to Japan to take part in the initial tests and was joined by Paul Smart when they went to the USA for more testing.

Before the V1s left Japan, a number of problems needed to be fixed including the breather system’s inability to keep all of the oil inside the engine and a slight problem that saw the piston crowns wilting. One by one the problems were resolved. Engineers were encouraged by 95hp from one of the V1s and a recorded top speed of 140mph.

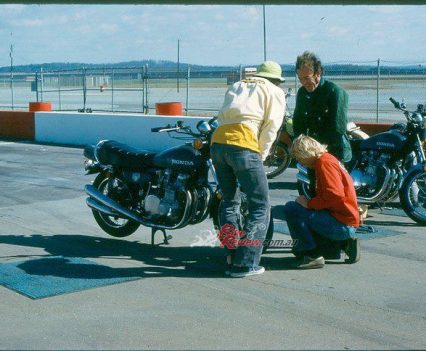

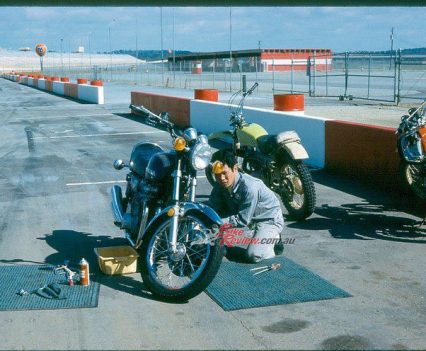

As the USA was the major market for the Super Four, KHI decided to run the bikes on American roads and see what broke. We’ve been lucky enough to track down a variety of pics of the two bikes from the testing in the USA. KHI did not want the press or anyone else to know these were Kawasakis so they painted them in Honda colours and stuck Honda badges on the tank! If you look carefully, you’ll see gaffer tape on the points cover which was branded with the Kawasaki name on the V1s.

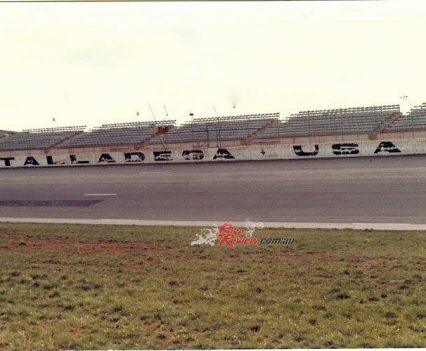

Based out of Los Angeles, the two bikes clocked up lots of hard miles at high speeds including a trip to Daytona and back with side-trips to various race tracks including Talladega in Alabama where some of pics were taken. Joining the previously mentioned riders in America was Japanese test rider Mr Kiyohara.

This was early in 1972 and at the end of the testing, the V1 bikes were returned to Japan where they were stripped and examined carefully. According to what I can find, the only problem area identified was excessive chain wear so the automatic chain oiler was either added or modified at this point.

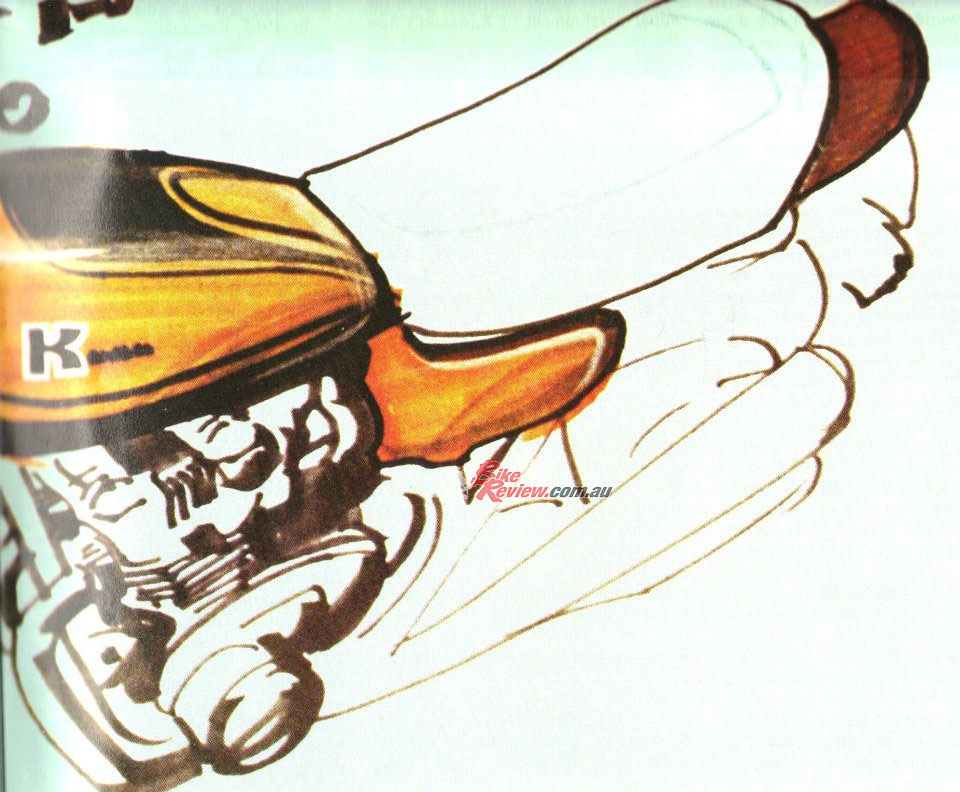

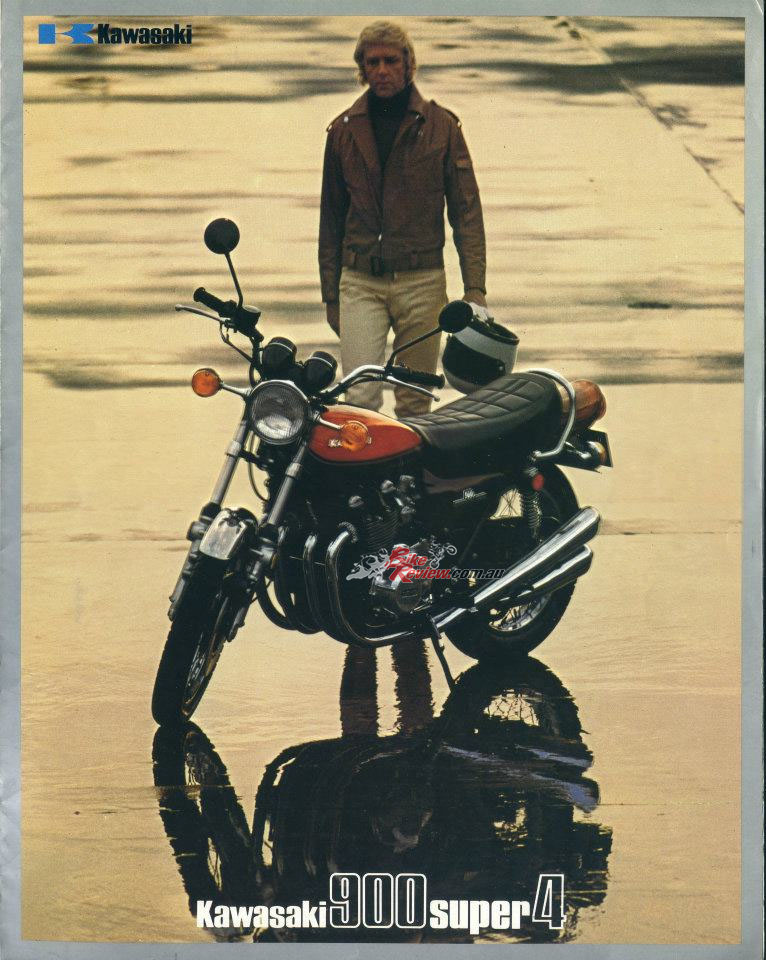

The paint design changed from the V1 when it became a Z1 and the final decision on colour scheme was made. The much-loved Candy Brown and Orange, better known as the Jaffa in Australia, was one colour option and the other was Candy Yellow and Green.

Also receiving a final touch-up was the points cover that lost the Kawasaki branding, replaced by the DOHC logo that was removed from the clutch cover.

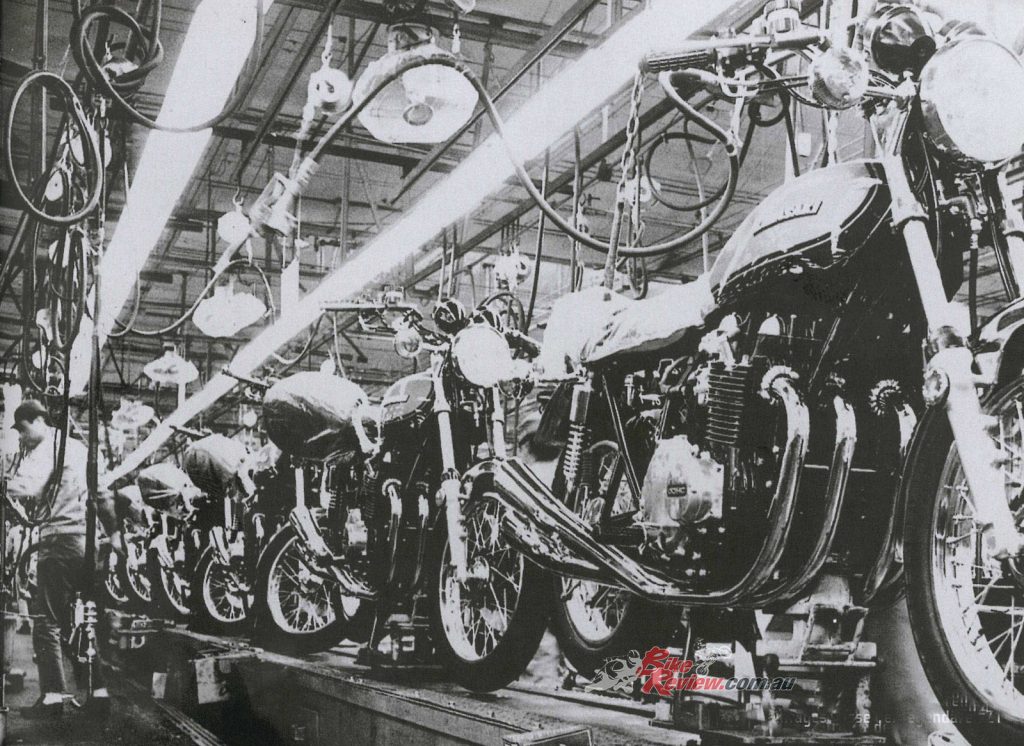

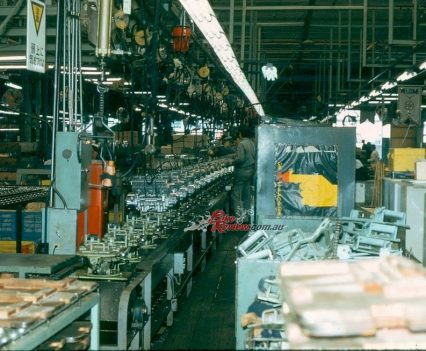

These were the final changes prior to the engine and frame numbers receiving their new Z1 prefix in time for the preview in June 1972 in Japan by a variety of the world’s leading motorcycle press. This was also a chance for KHI to listen to their feedback before ramping up production from the slow pace that had already been happening for a couple of months.

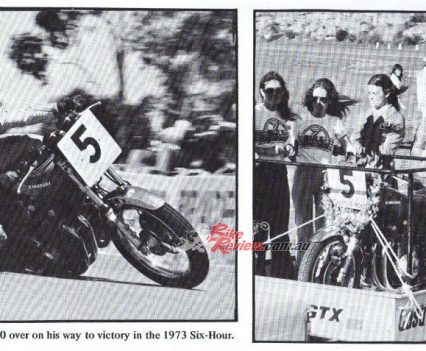

The official world launch was in September 1972 at the Cologne Motorcycle Show in Germany, mere weeks before the 1972 Castrol 6Hour on October 15. The first shipment of Z1s hit Australia in early October with at least one making laps of Amaroo Park during the 6Hour where it was ridden by the travelling marshals. Mike Steel and Dave Burgess won that race aboard a Kawasaki H2 750, the last win by a two-stroke in that race.

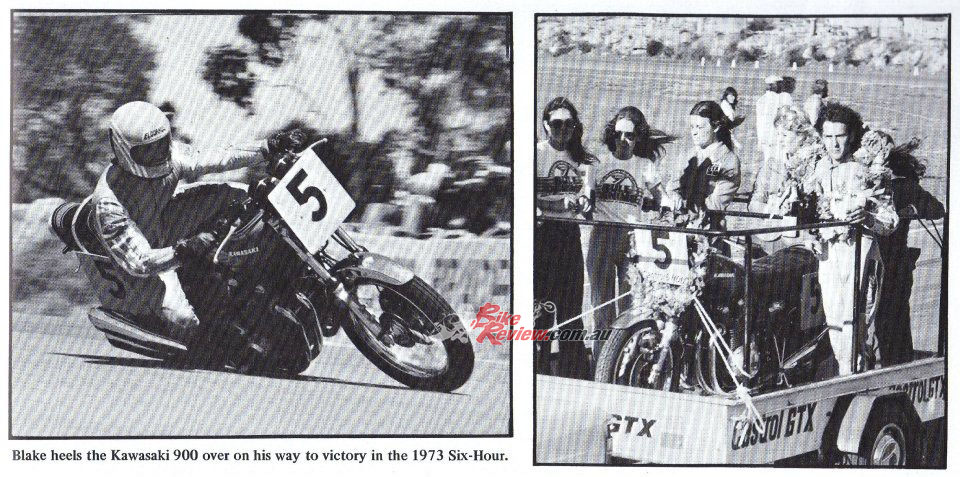

Ken Blake took over the Kawasaki Australia Z1 ride after Ron Toombs broke his ankle two weeks prior to the 1973 6Hour. Ken rode to an easy solo win. Blake teamed with Len Atlee for the win in 1974. Gregg Hansford and Murray Sayle shared the ride and the win in 1975. Kawasaki Z1 domination continued in 1976 when Jim Budd and Roger Heyes won. Four on the trot certainly didn’t harm the legendary status.

The first Z1 in Queensland was bought by Karen Shearer who, in company with Barry Taylor from Phase Four Motorcycles, proceeded to take it straight to Surfers Paradise International Dragway where it dislodged a valve shim and spat it straight out through the rocker cover! Scott Lynch was one of the crew that day and he said that a nice Japanese gentleman arrived a couple of days later with replacement parts and proceeded to fix the bike.

While fixing it he advised the Phase Four crew to open the valve clearances up slightly from the factory settings! In true stock trim, a Z1 would run 12.0 to 12.2 on the dragstrip. Out on Australian highways in the days before speed limits, the best you’d get out of a stock Z1 was 125mph, not bad for an engine rated at 82hp.

Unfortunately exact sales figures for the Z1 and subsequent 900s are no longer available but we can confirm that lots of them were sold!

Thanks to Greg Walker, I have seen a list of the first 10 production Z1s. Number 1 was retained by KHI and is now on display at Kawasaki World in Kobe. Walker himself owns number 10 and the other eight are still in existence.

There’s has always been something special about the Z1. I can still clearly remember the first one I saw in the flesh. I think it was my cousin Greg’s and it was parked in the back of my uncle’s garage. I was mesmerised and stood staring at the Jaffa tank and the sidecover badges. I don’t think I ever got over that moment and I hope I never do.

BY THE NUMBERS – 1972 to 1976 Z1/Z900

Here is a list of the first engine and frame numbers for each year of production as well as the retail price for each model. The engine and frame info is from the Kawasaki Recognition Manual (Part no: 99930-1001-02) and the pricing info came from Murray Sayle at Kawasaki.

1972 & 1973 – Z1

$1864 (1972), $1954 (1973)

Engine Z1E000001

Frame Z1F-000001

1974 – Z1A

$1998

Engine Z1E020001

Frame Z1F-020001

1975 – Z1B

$2154

Engine Z1E047500

Frame Z1F-047500

1976 – Z900-A4

$2250

Engine Z1E086001

Frame Z1F-085701

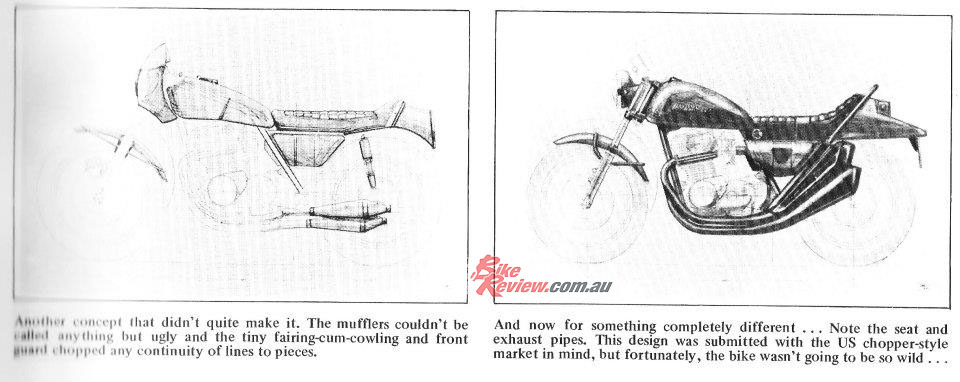

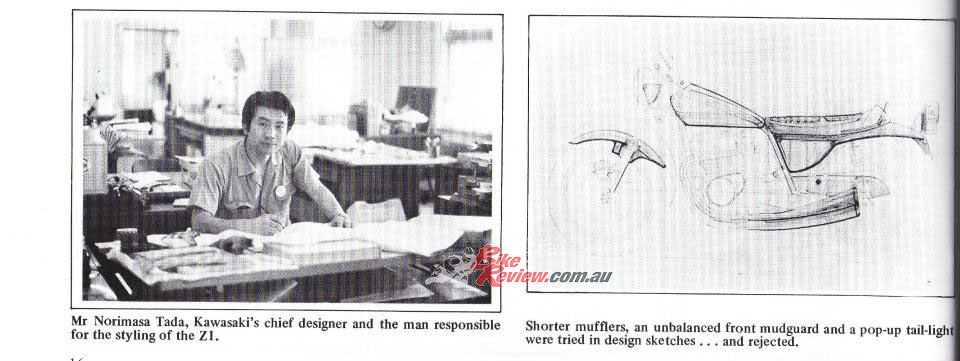

Z1 STYLING DESIGN DEVELOPMENT

Normally we do the reporting but when you receive information as valuable as this from a person as credible as the Z1 designer, Norimasa ‘Ken’ Tada, you have to run with it. Enjoy.

Styling is an important element in the industrial design development of every consumer product.

This is the story of my challenges to create a styling design to marry American motorcycle enthusiast sensibilities with the extraordinary performance character of the Z1.

Z1 DEVELOPMENT SCHEDULE

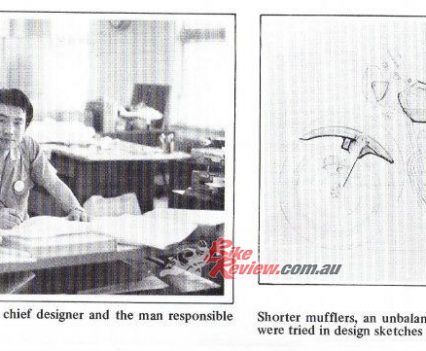

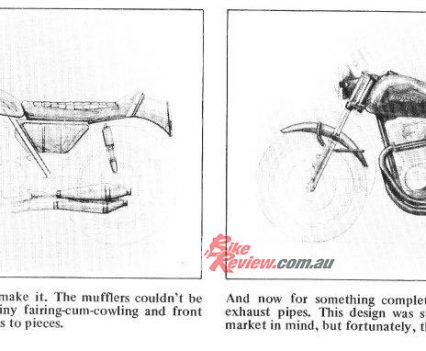

I was assigned to the exciting Z1 style design project on March 1, 1971 and given a seemingly impossible final mock-up completion deadline of March 31 to fit the established mass production start time schedule. Such a project would normally require four to six months and involve several assistants. I was to do it in one month by myself!

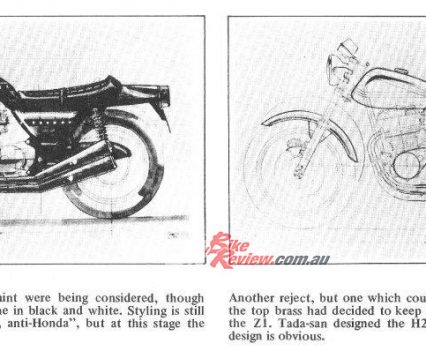

Akashi chief designer Tom Tomonaga, working with American designers in Santa Barbara, California, had completed an earlier design mock-up for the N600 (750cc) model in late 1968. After Honda announced their CB750 in October 1968, the N600 project work was put on hold. Mysteriously no new Z1 (T103) design project had been initiated since that time for one of the most vitally essential and important models in Kawasaki history.

So I became responsible to fill the black hole. I made a murderous one-month schedule ignoring overtime, Saturdays, Sundays, all personal matters, and asked my wife to forget that she had a husband for a month. Product Planning Manager Sam Tanegashima directed me to get the job done on time without budget worries. So I contracted two of Kawasaki’s best outside suppliers to develop some mock-up styling parts under my direction. The breadth and intensity of the tasks involved seemed completely overwhelming at the time. With hindsight, this became the most rewarding experience of my professional career: working alone with complete concentration to create Z1 styling in record time.

Z1 STYLING DESIGN POLICY

Z1 STYLING DESIGN POLICY

- To implement the KMC (Kawasaki Motors Corp) ‘3-S’ styling concept: that was Slim, Sleek and Sexy.

- Drastic differentiation from all rival model styling, especially the CB 750 Honda.

- Full freedom for innovation and creativity for American customer appeal.

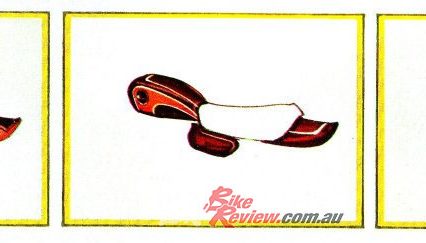

- Develop American requests for ‘teardrop’ tank shape and tail cover design.

Like a Zen monk, I often meditated in front of the Santa Barbara mock-up, the only physical example at hand that embodied creative American tastes, even though it fell short of my ideal.

At Kawasaki, engine parts had never been developed by a styling designer. Black cylinders and DOHC on the engine cover were visuals I developed. Engine design chief Ben Inamura objected to the DOHC badge. “This is unnecessary. Everyone can easily see this feature on the engine itself.”

But I insisted and prevailed. It highlighted a differentiation to Honda’s CB750 SOHC, and spoke performance even to those with no idea what it was or knew about its mechanical superiority.

DESIGN CAREFULLY INTEGRATED RIDER POSITIONING

At 177 cm (5′ 10″), exceptionally tall for Japanese, both test rider ‘Big Eyes’ Yamamoto and I were about average American rider height.

The mock-ups of the four most important elements: the fuel tank, seat, side covers and tail section were my personal fabrications. Other parts went to the two outside suppliers with my sketches and detail instructions. The final mock-up design parts were all finished in flat white to allow better shape discernment, independent of C & G (colour and graphic) considerations.

Z1 900 DESIGN PRESENTATIONS

Miraculously completing my work on March 31, I made a formal presentation to key factory people including all Z1 project engineers. Reactions were positive but we all knew final approval depended on the KMC marketing team with USA sales responsibilities.

On April 5th, 1971 I flew to Los Angeles with Z1 engine design chief Ben Inamura and Sam Tanegashima, the Product Planning Manager. This was my first international flight. Although exhausted from non-stop work during the past month, I could get no sleep. While proud and confident about my mock-up, KMC was famous for its nasty design critiquing.

They had rejected our styling projects several times in the past. I fretted that non-acceptance would require a new project, probably not by me and cause a production delay to the consternation of all Akashi engineers and production guys. Whisky and beer didn’t help; I was awake all the way to LA. Sam drove us in a rent-a-car to Santa Ana and checked us into the Vagabond Motor Hotel, a small motel near KMC offices. I re-assembled the mock-up from its shipping crate. We prohibited entry, even to the room cleaners and must have seemed strange and hateful guests to the motel staff.

The responsible American staff arrived for my presentation, entered the room quietly and began their intensive inspection. I was trembling with excitement and at the same time dreading a ‘Not Acceptable’ conclusion. Happily they were quite satisfied with my new baby. KMC President Hamawaki came to me, ‘Nice job. We like it,’ and shook my hand in congratulation. Z1 styling was accepted! It was the happiest moment of my life. I felt tears of joy flowing down my cheeks.

One improvement was asked, ‘It looks a bit like an expectant mother. Make it a slimmer zapper.’

Sam drove me to Disneyland in Anaheim saying he would pick me up at the entry gate three hours later. I had to fly back to Japan immediately for production schedule tasks, so my only visit impressions were the ratty Vagabond Motor Hotel and Disneyland. Feeling completely relaxed for the first time during the long sleep-starved month, I slept deeply all the way back to Tokyo.

BACK IN AKASHI

BACK IN AKASHI

First of all, I worked to modify the ‘expectant mother’ image by slimming the fuel tank. With assistants, all details were soon finished and we turned to colour and graphics design. The Z1 was born! Everyone, including me, was very happy with the results. The torch was passed to production engineering designers to make drawings. A final Z1 project was added somewhat later. Sam had us design special engraved ignition keys as gifts for the four American motorcycle magazine editors who came to Akashi in June 1972 for a Z1 press preview.

I was promoted to manager level soon thereafter. The pay increase was welcome but I became busy supervising young designers, watching budgets and attending meetings. I could never again work to design a motorcycle with my own hands. As a design professional and motorcycle lover I still dream of the surge of that intense and crazy single month devoted to Z1 superbike styling.

SPECIAL THANKS TO: Murray Sayle, Norimasa Tada and Steve Bagley. Thanks also to Roy Bacon and Scott Lynch.

Z1 900 INFORMATION SOURCES

Now, during the course of research for this article I came across a lot of information that would be of interest to Z1 fans. If you want to know the difference between the ‘7’ on a 1972 and 1973 tacho, you could check out the following websites or Facebook groups. They can even share with you the date codes for front brake rotors and various other parts.

Facebook: Z1 Owners Club; Kawasaki Z1 900/Z 900/ KZ 900; Kawasaki Z1 Fan Club.

Websites: kawasaki-z-classik.com; z1enterprises.com; doremi-co.com

You can also find our full test on the new fot 2017 Kawasaki Z900 here.

February 14, 2020

Hi

do we know an actual date – at least w/c or w/e – for when the very first Z1s [so frame / engine numbers = low hundreds] rolled off the production line in Japan ? I believe early Sept 72 it was definitely happening, but August, or even were they underway late July 1972 ? There must be a reasonably accurate record somewhere, but by some quick Google searches I couldn’t yet find it. Thanks

May 6, 2020

Nice article.

Thanks.

I have owned over 40 (probably closer to 50) motorcycles since 1974 and the big Z (actually a 1977 Z1000A) that propelled myself and my long suffering life partner / favourite pillion of many moons Karin for over five years back in the mid eighties is still her fave of all time.

Tough (as in made of steel) fast and handled OK / brakes OK by the standards of the day.

One of the best looking motorcycles of all time.

On a par with the Triumph Bonneville in being instantly recognisable.

I’ve got several beautiful bikes now (at 61 years) but I’d love to find an old Z to join them.

The only bike I could bring home and Kaz would ask not what it cost but “where’s my skidlid”? and “where are we going for a ride”?

April 14, 2021

I find it amusing how the Honda CB750 had a world release in September of 1969 and released a new colour Gold for the 1970 model year at CB750-1019210,. The 1969 made and model bikes both Sandcast and diecast bikes fetch a premium price today. The Z1 world release was also in September of 1972, and near a quarter of Z1 20,000 production was made and dated on the frame 1972 yet the Kawasaki boys beat on about it being a 1973 model. Yet a ‘72 made Z1 will pull more money. I am fortunate to have both a ‘69 CB and a ‘72 Z1 they are both Awesome bikes and a joy to ride, but the prices being paid are nuts.

April 26, 2021

I have a Z1 with frame 01569 and engine 01708, can anyone tell me when the bike was build ?

June 20, 2021

3rd week of October 1972

July 30, 2021

@NewYorkSteak,Thank you !!! I just found and bought frame Z1F05735 and engine Z1E05638,

Can you tell my when this bike was build ? Thank you

October 26, 2021

I saw a Z1 in September 1972 in Ft Worth Texas. I happened to be riding my red 1970 H1, and due to heavy traffic, I had no problem catching up to him. He said he was a factory test rider. A few months later, in May 1973, I bought my own Z1. It was one of the first in my area of Florida. Mine had engine/frame numbers in the mid 3000 range. I ended up meeting another guy that had come down from Indiana with a Z1 that had engine number 00043. We blasted all around the west coast of Florida on those things. Later on, I installed Dunlop K81 tires and Koni shocks. That made a big difference in the handling, of course. After joining the military, I got stationed in Monterey, California for 1 year and spent lots of time riding it at Big Sur and Carmel Valley, enjoying the improved handling. Rode it back to Florida later.

November 2, 2021

What an awesome story. I wonder who the test rider was. Amazing memories it must have been an exciting time in motorcycling.