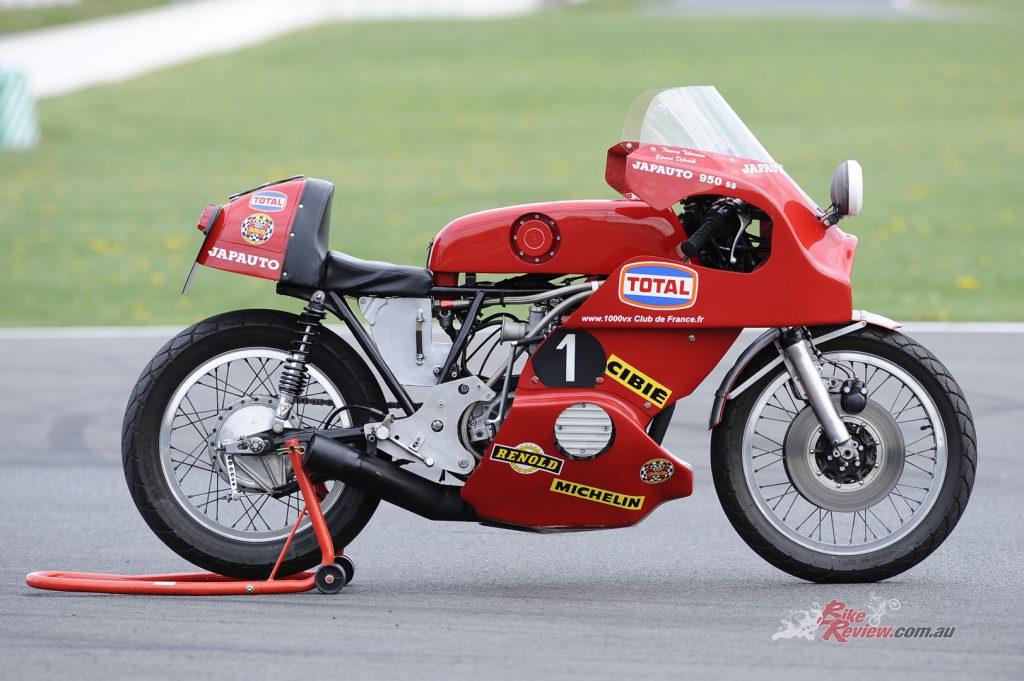

Japauto started life as a French Honda importer but ended up pathing the way for Honda's production racing domination with their amazing 950SS. Words: Alan Cathcart.

Legend has it that Dick Mann’s Daytona 200-miles win on a factory-built Honda Formula 750 racer in March 1970 represented when Japanese in-line fours first established their domination of production-based road racing, but in reality it was the Japauto 950SS…

The CB750 marked the turning point for Honda on the world stage. Here’s the history behind the forgotten Japauto Honda 950SS…

Read Alan’s racer test of the 950SS here…

This debut victory on the world stage of Honda’s iconic CB750, which had changed the face of motorcycling for ever on reaching showrooms the previous year, marked the beginning of the modern era of road racing, say many students of two-wheeled history.

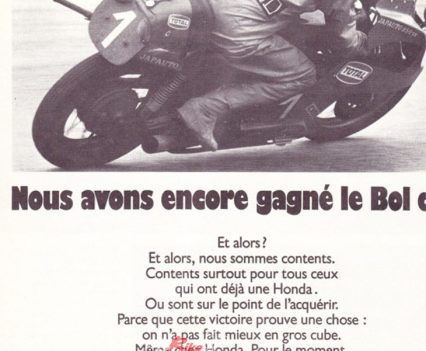

While many mark Dick Mann’s Daytona 200-miles win on a factory-built Honda Formula 750 racer in March 1970 as the begging of Honda’s domination. It was really the 1969 Japauto CB750’s win at Bol d’Or that started it all.

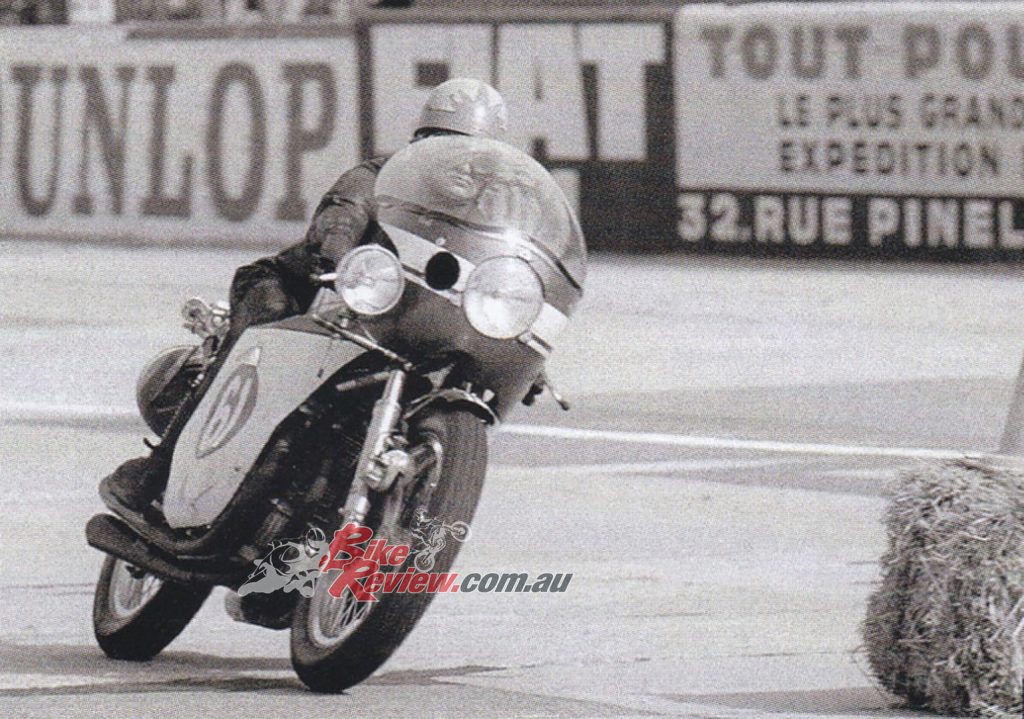

Except, that’s actually not the case, for already on September 13, 1969, France’s largest Honda importer, Paris-based Japauto, had taken a CB750 to victory in the classic Bol d’Or 24-Hour marathon, just a matter of weeks after receiving the first of the literally thousands of similar bikes they would sell from their landmark dealership in the shadow of the Arc de Triomphe, opened in 1968.

Japauto patron Christian Vilaséca was a far-sighted entrepreneur who, after taking control of his family’s large GM car dealership on his grandfather’s death in 1961, founded Japauto in 1966 to import Honda motor cars – his first order was for 150 examples of the S800 sports car, which disappeared practically overnight! But Vilaséca also planned to cash in on what he was convinced would be Honda’s domination of the motorcycle market, which would grow exponentially as they developed new models. He wasn’t wrong – and the debut of the Honda CB750 at the Tokyo Show in October 1968 was the first step in Japauto’s explosive growth, which would quickly see it become Europe’s largest motorcycle dealership, selling more than 1,000 new bikes each year.

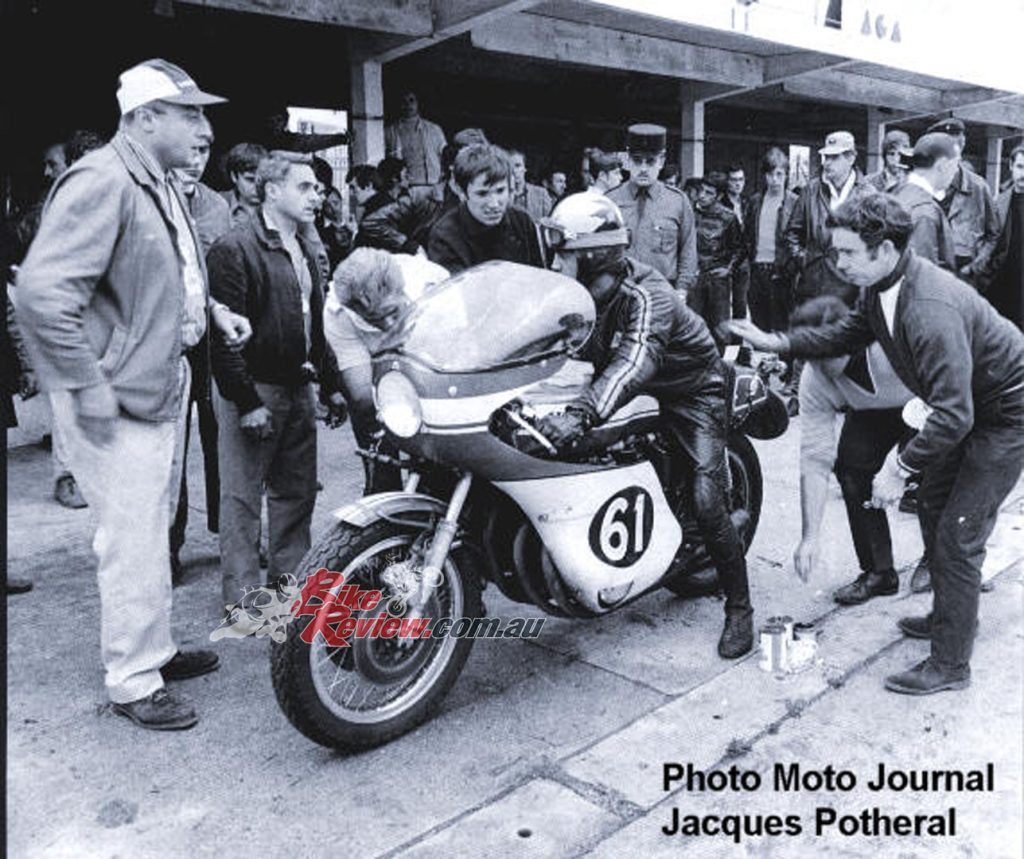

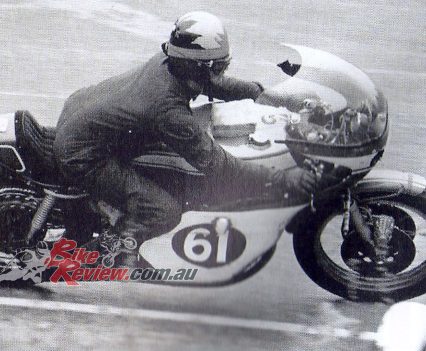

The following year, the first examples of the first ever four-cylinder Japanese streetbike reached the Japauto showroom, and while supply was initially much more problematic than sales, Vilaséca was eager to demonstrate that the new bike was reliable as well as fast, dependable as well as sexy. As a fan of racing, the obvious gambit was to combine business with pleasure, so he arranged for his mechanics in the dealership to prepare one of the first examples of the CB750 four they’d received to compete in the 1969 Bol d’Or 24-Hour race to be held at Montlhéry, just outside Paris – a classic marathon then being revived after an eight-year absence by Moto Revue magazine.

To ride the bike, Japauto shop manager Robert Assante, himself an able part-time racer, recruited 19-year old Daniel Urdich who’d rather amazingly finished second overall in the Le Mans 1,000km that year on a 250cc Honda CB72 twin, and would have signed up his teammate Robert Gilloux as well, except that at 18 years of age the lad wasn’t allowed to race anything bigger than a 250! Assante therefore gave the second ride to another 19-year old in just his second year of racing aboard a 305cc Honda CB77, who happened to be working as an apprentice mechanic in the Japauto workshop. His name? Michel Rougerie!

Honda Japan had already organised a team of all British riders to race in the 1969 Bol d’Or. But, it was discovered three days before the start that only French licence holders could enter, so Japauto stepped up and won!

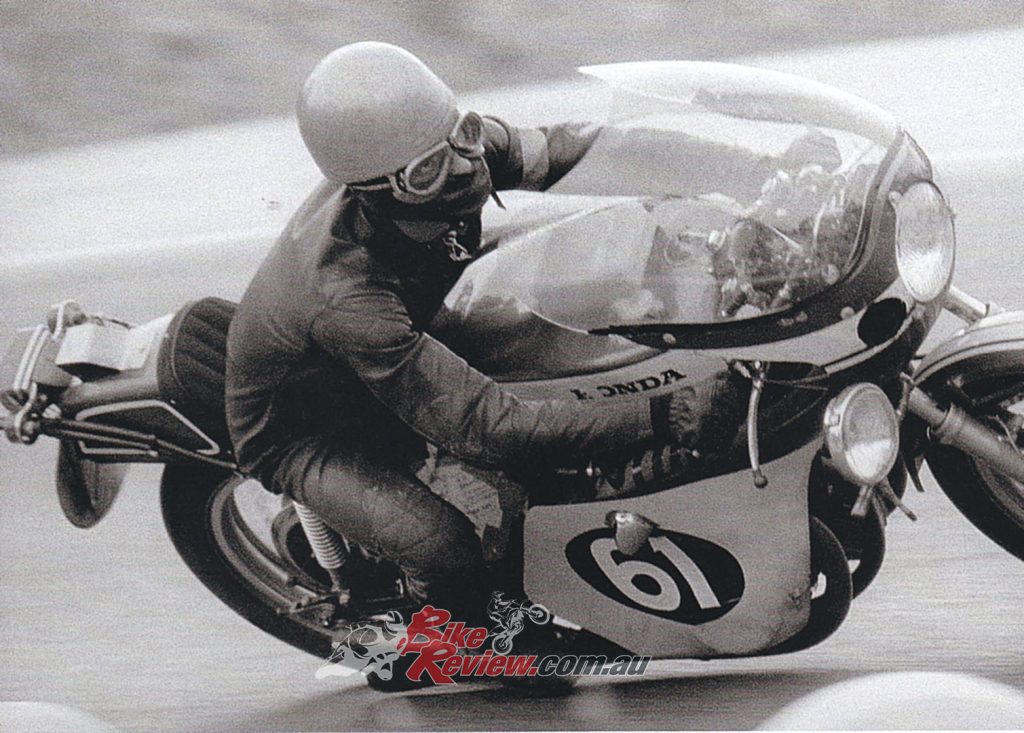

But Honda competition manager Yoshio Nakamura had also arranged to send a race-prepared CB750 from Japan to take part in the race, and having already assigned the firm’s Honda Britain subsidiary the task of racing the new model outside Japan – Dick Mann was only added to the British three-rider team for the Daytona 200 as an afterthought – GP riders Bill Smith and Tommy Robb were originally named to ride the bike in the Bol d’Or.

Check out our Throwback Thursdays here…

That was until it was discovered at the very last minute – like, three days before the start! – that only French licence-holders could take part in the race. So Japauto took over the factory bike, and its teenage riders Rougerie and Urdich scored a fairytale win to deliver the Honda CB750’s debut victory in its first-ever race outside Japan, which was also the first time a 24-Hour Endurance race had been won by a four-cylinder motorcycle.

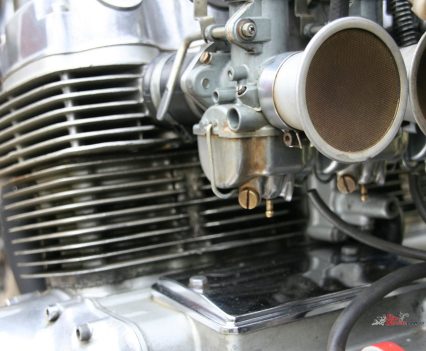

Riding a factory-modified CB750 streetbike, whose motor producing 72bhp at 8,000 rpm (against the stock CB750’s 67bhp at the same revs) was fitted with the prototype of the later factory race kit, complete with race gearbox, megaphone exhausts and no air filters on the stock 26mm Keihin carbs, and housed in an unmodified frame except for twin front discs and 200mm twin-leading shoe magnesium drum rear brake (against the street CB’s single front disc and SLS rear).

Rougerie/Urdich finished ten laps ahead of a trio of 500cc H1 Kawasaki two-stroke triples, the Honda’s big rival in the Japanese performance marketplace.

Rougerie/Urdich finished ten laps ahead of a trio of 500cc H1 Kawasaki two-stroke triples, the Honda’s big rival in the Japanese performance marketplace, that were the best of the rest of the 54 starters. The commercial benefits this win brought in its wake gave the enthusiastic Vilaséca – who’d personally helped staff the pit, working as refueller throughout the race – the excuse he needed to take Japauto racing seriously.

The 1969 Bol d’Or winning Honda CB750 was sent back to Japan to be used as a prototype for the famous Dick Mann Daytona winner.

The 1969 race-winning bike had been sent back to Japan – it was essentially the prototype for Mann’s Daytona-winner – so for the 1970 Bol d’Or Japauto developed its own big-bore version of the CB750 engine, which it also marketed as a kit for streetbike customers.

Using 70mm bore French-made Brétille pistons with offset pins, fitted with CB450 rings and running in the honed-out stock CB750 cylinder block – fortunately, there was space between the cylinder bores for this – while retaining the standard five-bearing forged one-piece crankshaft, turned the original longstroke 61 x 63 mm 736cc street motor into a meatier, more potent and especially more torquey 969.80cc short-stroke package.

This was fitted in a lightly reinforced CB750 street chassis with twin front discs and four open meggas, carrying a massive 25-litre Read-Titan fibreglass fuel tank and clad with a blue-and-white three-piece Churchgate fairing, both imported from Britain. Ridden by Japauto manager Assante and Daniel Rouge, the so-called Monstre du Bol initially ran at the front of the race, but was delayed first by gearbox problems causing the loss of fourth gear, then by a crash which finally led to the alternator breaking off the end of the crank. The patched-up bike limped home in 20th place, behind the race-winning Smart/Dickie Triumph-3.

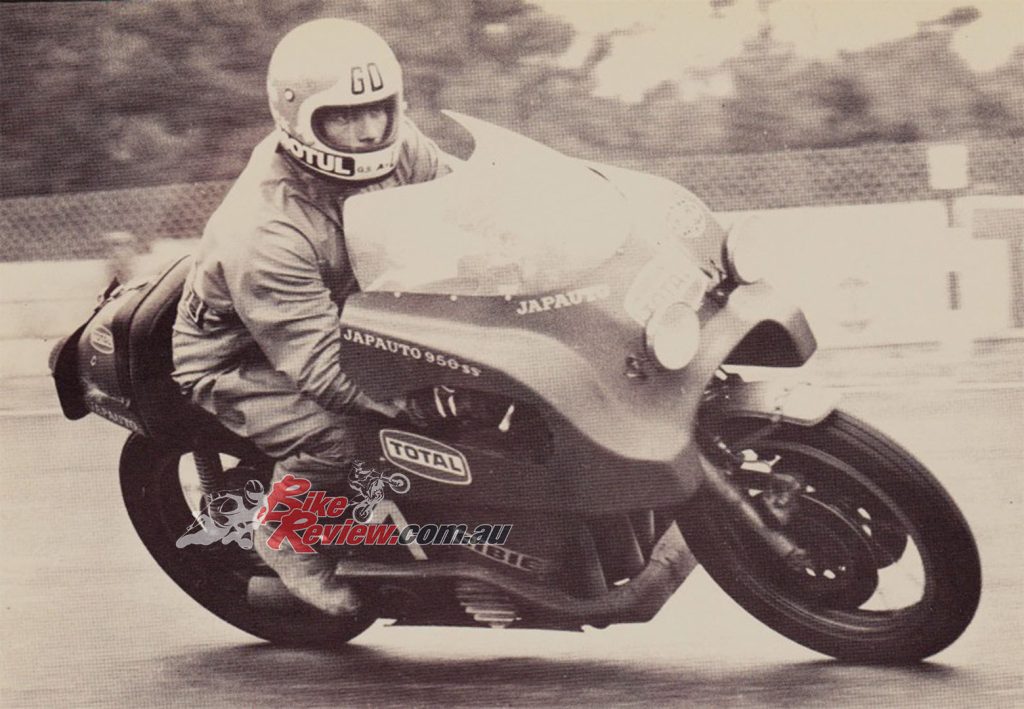

1971 marked the beginning of the 950SS era. The highly modified CB750 was an absolute weapon for the early 70s.

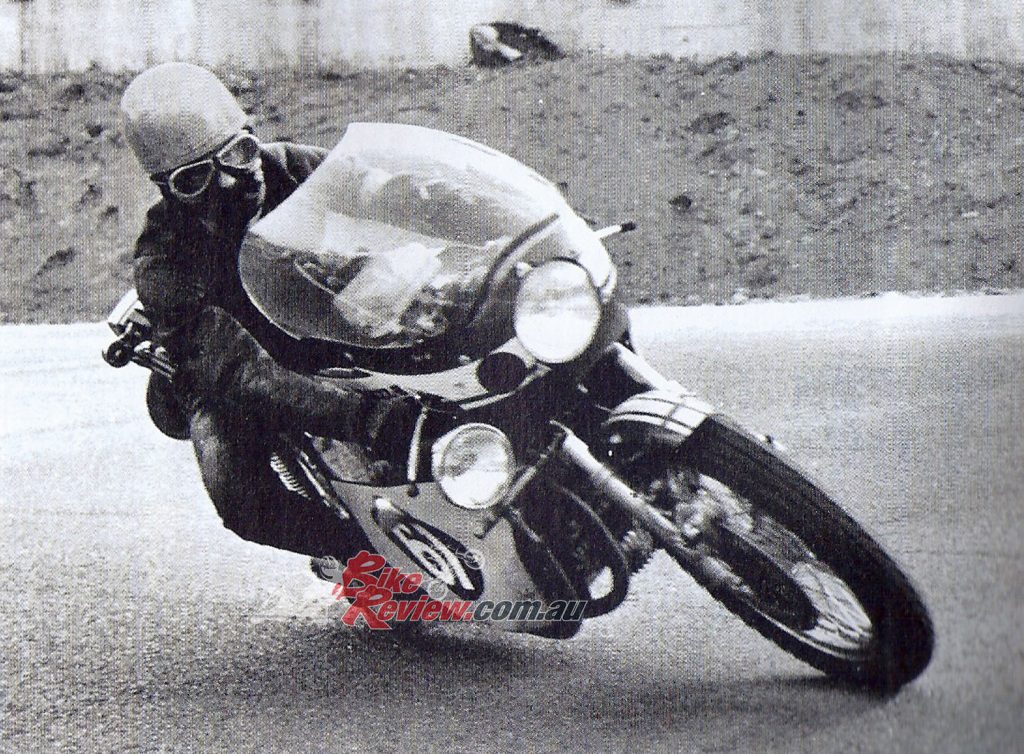

This disappointment caused Christian Vilaséca to reason he should enter a second backup machine for Japauto’s annual Bol d’Or foray, so with the 1971 race transferred to the Bugatti circuit at Le Mans, Japauto prepared a pair of bikes in its new competition workshop in nearby Levallois, staffed by the dealership’s regular mechanics working after hours and at weekends under chef d’atelier Jean-Claude Ruban, an ex-Johnson Marine engineer.

Assante again nominated himself as one of the riders, this time teaming with Roger Ruiz, and a second machine for Thierry Tchernine and Christian Bourgeois. Attempts to develop a competition frame better suited to the big-bore engine – which Vilaséca had put on sale to the public under the 950SS label, fitted with Japauto side covers but still using the original CB750 frame – proved fruitless. Moto Revue magazine tester Bourgeois nicknamed what had seemed the most promising of these, made by local artisan Gilbert Chatelard, as Le Serpent de Mer – the sea serpent – on account of its handling when he rode it at Rouen!

So the previous year’s bike was essentially cloned, but fitted with a slimmer fairing wrapped around the stock frame, while the engine contained more Japauto performance parts, including lighter Brétille 70mm-bore pistons, now with Meillor rings. But Assante/Ruiz suffered once again with gearbox problems, eventually retiring, while Tchernine/Bourgeois were classified 12th in spite of being sidelined themselves with similar problems just 45min before the end of a race won yet again by a Triumph triple, this time ridden by Tait/Pickrell.

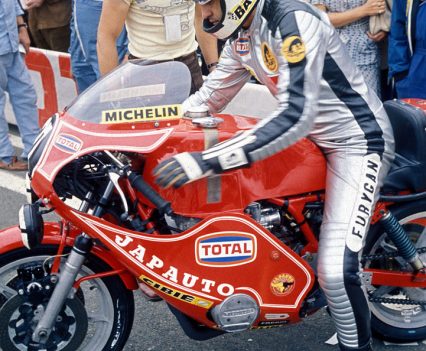

For 1972, it was time to go all out, no more losing. The Japauto was becoming less of a Honda and more of a full custom machine.

Getting beaten twice over by the only other multi-cylinder four-stroke in dealer showrooms wasn’t on Vilaséca’s agenda, so for 1972 he decided to go for broke – especially as Kawasaki’s new 903cc four-cylinder Z1 was known to be on the horizon, and Japauto needed some good publicity to counter that impending commercial threat. So Vilaséca commissioned three Dresda frames from British chassis specialist Dave Degens, himself an expert Endurance racer who’d won the 1965 Barcelona 24-Hours on his self-built 750cc Dresda Norton, clothing them in distinctive bodywork with a one-piece seat/tank unit, painted in different colours matching the French tricolour flag!

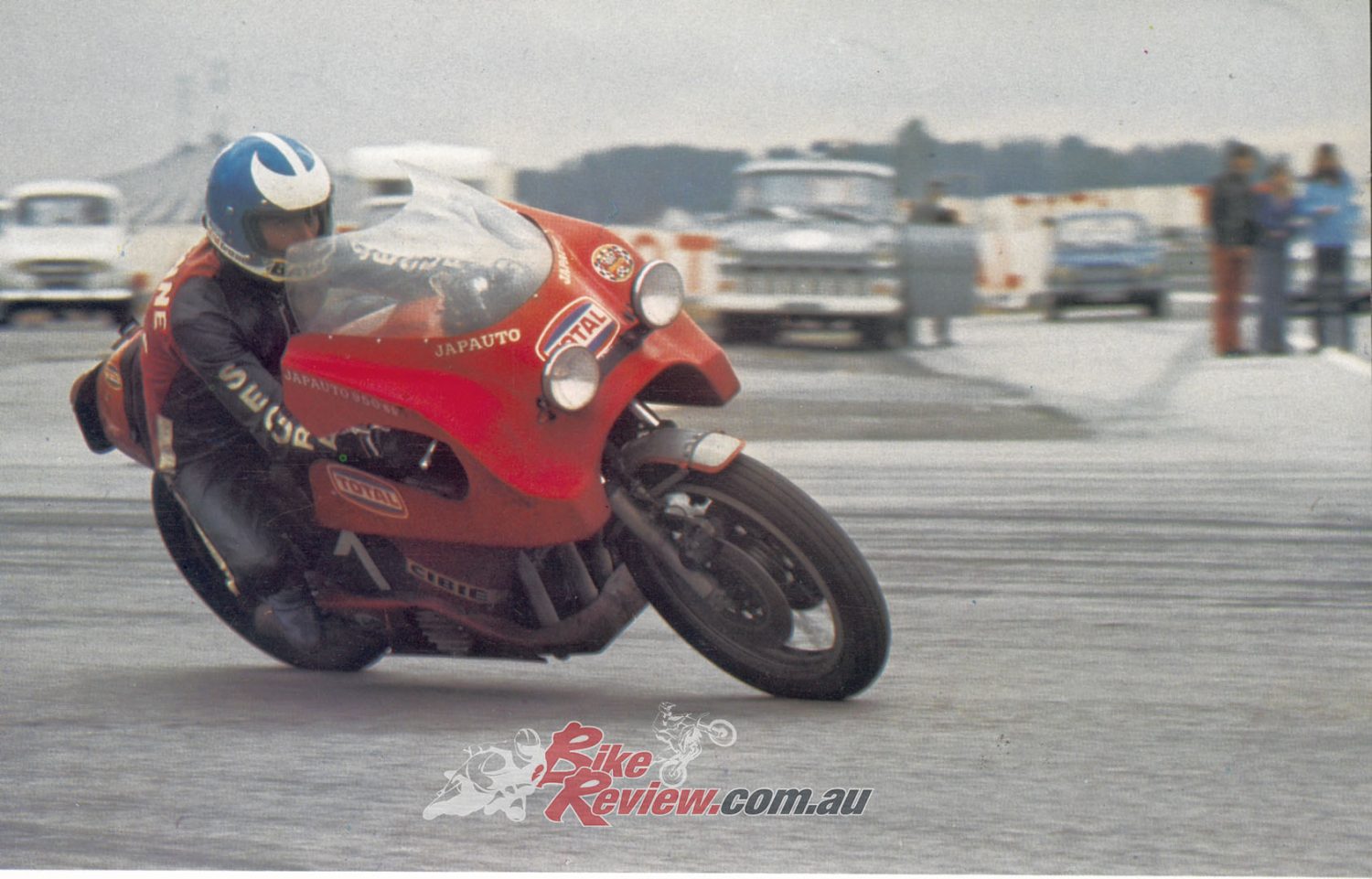

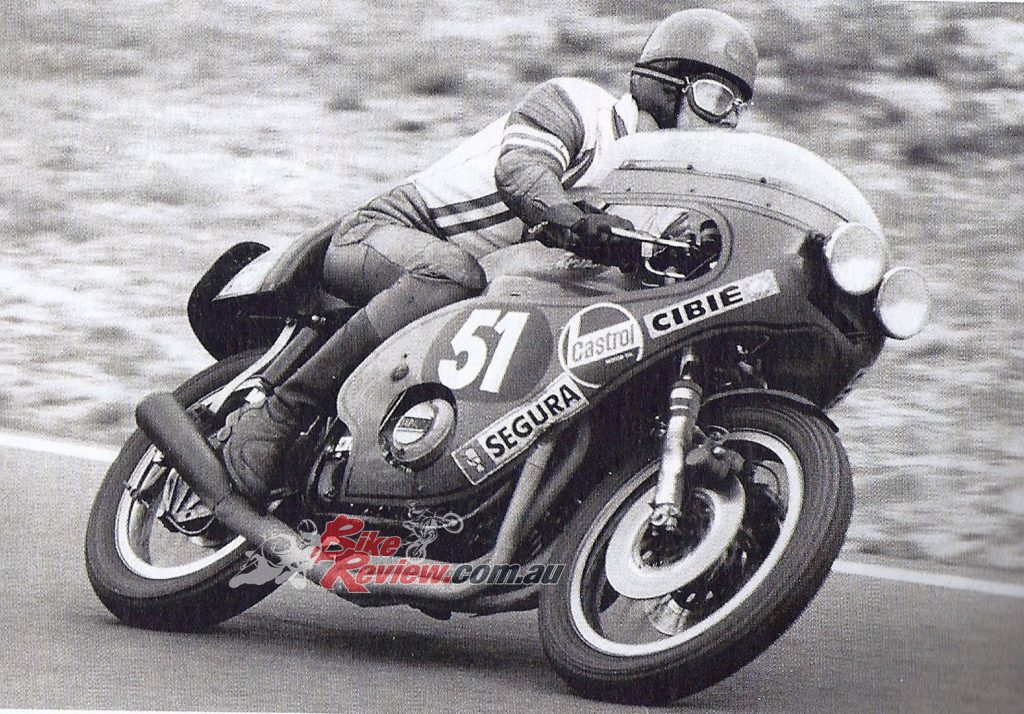

The blue bike of Bourgeois/Tchernine retired with a broken crankshaft, the white one of Assante and Guido Bettiol finished ninth – and the red example of this entente cordiale, comprising a French-developed Japanese engine with British five-speed Quaife gearbox to resolve the transmission problems of the past, fitted in a British chassis which both handled better and delivered a bike that at 170kg dry was significantly lighter, was ridden to victory by Roger Ruiz and his new teammate, Gérard Debrock in front of a crowd of 70,000.

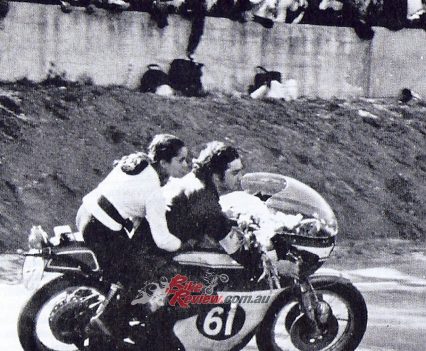

Gerard Debrock en route to the podium on a fans shoulders after winning the 1972 Bol d’Or on the 950SS.

“Our main rival was the very fast factory Moto Guzzi, but we stuck in their wheeltracks until midnight, when it rained hard and they fell back,” said 30-year old Debrock, a gifted amateur rider who retired early from racing bikes in 1976, to return to managing his family’s metal foundry. “After that we managed to stay ahead of the Godier/Genoud Egli-Honda, and we took the win two laps ahead of them, thanks to an excellent bike and a very good team.

I was riding it when we took the chequered flag with the crowd invading the track, and it was a pretty good moment. Some spectator carried me around on his shoulders for about 20 minutes, until we eventually reached the podium – he must have been a rugby player!” After that, all future Japauto racers were painted in what was deemed to be the team’s lucky colour of red, and that applied to roadbikes.

For 1973, Vilaséca originally intended to use the same bikes, albeit fitted with ultra-distinctive shark-nosed bodywork made by Etablissements Morin at Melun in the south of Paris.

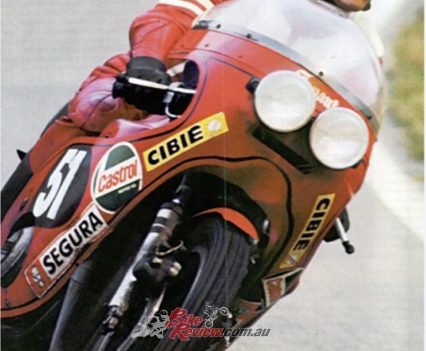

For 1973, Vilaséca originally intended to use the same bikes, albeit fitted with ultra-distinctive shark-nosed bodywork made by Etablissements Morin at Melun in the south of Paris, with twin externally-mounted Cibié headlamps. The concave curve to the protective fairing’s museau (‘snout’!) was claimed by its creator Claude Morin at Moto-Sport Design to increase downforce on the front wheel.

“In a warmup 10-Hour race at Montlhéry, the Bol d’Or-winning bike’s Dresda frame snapped in half, Vilaséca decided to switch back to the reinforced original CB750 chassis.”

But in a warmup 10-Hour race at Montlhéry, the Bol d’Or-winning bike’s Dresda frame snapped in half, and while this was doubtless due as much as anything to the corrugated concrete surface of the old Autodrome’s bankings, Vilaséca decided to switch back to the reinforced original CB750 chassis, still fitted with the distinctive Japauto bodywork which now included a Zenith quick-filler in the 25.5L tank.

A shakedown for this cocktail in the Le Mans 1000km race went well, with Roger Ruiz and new recruit Gérald Garnier finishing second behind the victorious Kawasaki 750 H2 two-stroke triple of Baldé/Léon, with Gérard Debrock, now teamed with Thierry Tchernine, third. In the Bol d’Or 24-Hours run on the same circuit in September blighted by 15 hours of torrential rain, it was Debrock/Tchernine – both skilled wet weather riders – who narrowly made it two wins in a row and a third in five years for Japauto, leading the race for 22 hours to finish two laps clear of the Guili/Renouf Kawasaki Z1, with the Dähne/Green works BMW just another lap down in third place out of the 58 starters.

Funnily enough, the bike actually went faster without the weird fairing on. But the added protection aided riders in the heavy rain.

“Because of the weather, the protective bodywork was an important factor in our victory,” said Debrock. “However, when we first used it in practice for the Le Mans 1,000km race in May, we couldn’t do competitive lap times. So we took the bodywork off – and immediately went two seconds faster, with a naked motorcycle! But in spite of that, Mr.Vilaséca insisted that we raced with it, and he was right – we finished 2nd and 3rd in the dry in the Le Mans race, and then it protected us very well in all that rain during the Bol – you can’t discount the extra comfort it provided.”

The fairing also provided a distinctive personality for the new Japauto 1000VX road bike. Photo Credit: Moto Antigus.

It also provided a distinctive personality for the new Japauto 1000VX road bike (see more photos of it here on Moto Antigus), which Honda France specifically permitted its largest dealer to create out of a standard K0 to K6-model CB750 road bike, with the approval of the Honda factory. The 1000VX’s standard frame carried twin front discs, Koni or DeCarbon shocks, and a lightly modified version of the Bol d’Or-winning bodywork, with a pair of big Cibié H-4 headlamps…

This was powered by what was effectively Japauto’s own 70 x 63 mm 970cc engine, with new lightweight Bretille pistons running in the cast-iron sleeves of a specially-made JPX big-bore cylinder block, with more extensive finning. Together with a 4-1 Laborderie exhaust, this transmitted between 85bhp and 100bhp to the rear wheel via a duplex drive chain and smaller 43T rear sprocket, depending on the customer’s chosen level of tune.

Cast aluminium JPX wheels were an option to the stock 18in rear and 19in front wires, always shod with Michelin tyres as Japautos usually wore in races, and it was later even possible to specify a full Bol d’Or Replica complete with PEM’s Japauto frame. Around 250 examples of the Japauto 1000VX were built during the next five years, before Vilaséca decided to call a halt to its manufacture in 1978 – with the impending arrival of Honda’s new twin-cam 16-valve CB900FZ in February 1979, the existence of a single-cam eight-valve Japauto big-bore special no longer made sense.

Japauto had built a turbocharged version of the 1000VX in 1976, fitted with a US-built Sigerson turbo. It never reached production, though. These streetbikes carried the newly-created Japauto motorcycle badge, depicting the head of a wild buffalo complete with horns, which Christian Vilaséca – himself an avid big game hunter proud to have bagged what he claimed was the head of the biggest buffalo ever shot, whose head hung as a trophy on the wall of his home! – admired for its tenacity, aggressiveness and endurance. These were qualities he sought for Japauto’s race bikes – and the two trophies on the badge naturally depicted the firm’s two Bol d’Or victories.

In 1974, Debrock was deprived of the chance to register a personal hat-trick of Japauto Bol d’Or victories, having stood his ground when Christian Vilaséca refused to pay him the same riding salary as Tchernine, in spite of his pair of wins. This year, though, instead of using the Le Mans 1,000km as a warmup race, the Japauto boss opted instead to race in the gruelling Barcelona 24 Hours in July – a decision occasioned by the fact that Spain had become an important export market for Japauto.

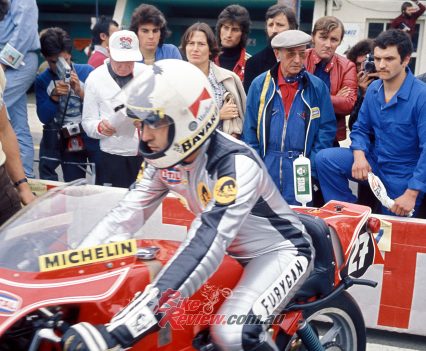

Gerard Debrock en route to victory at the 1972 Bol d’Or. Imagine what could’ve been if he had been paid right.

With the import of Japanese motorcycles banned under the Franco government in order to protect the local industry, purchasing a Japauto which was deemed to have at least 51% of its value emanating from elsewhere than Japan (including not only parts, but the cost of assembly) was a convenient if costly way for Spain’s wealthy elite to buy themselves a four-cylinder Honda – made in France! 72 Japautos were imported into Spain in this way, providing the canny Vilaséca with a lucrative sideline to his main business, and 30 examples of the 500VX, based on a CB450 twin, found their way there, too.

“In 1974, Debrock was deprived of the chance of hat-trick Japauto Bol d’Or victories, having stood his ground when Vilaséca refused to pay him the same riding salary as Tchernine…”

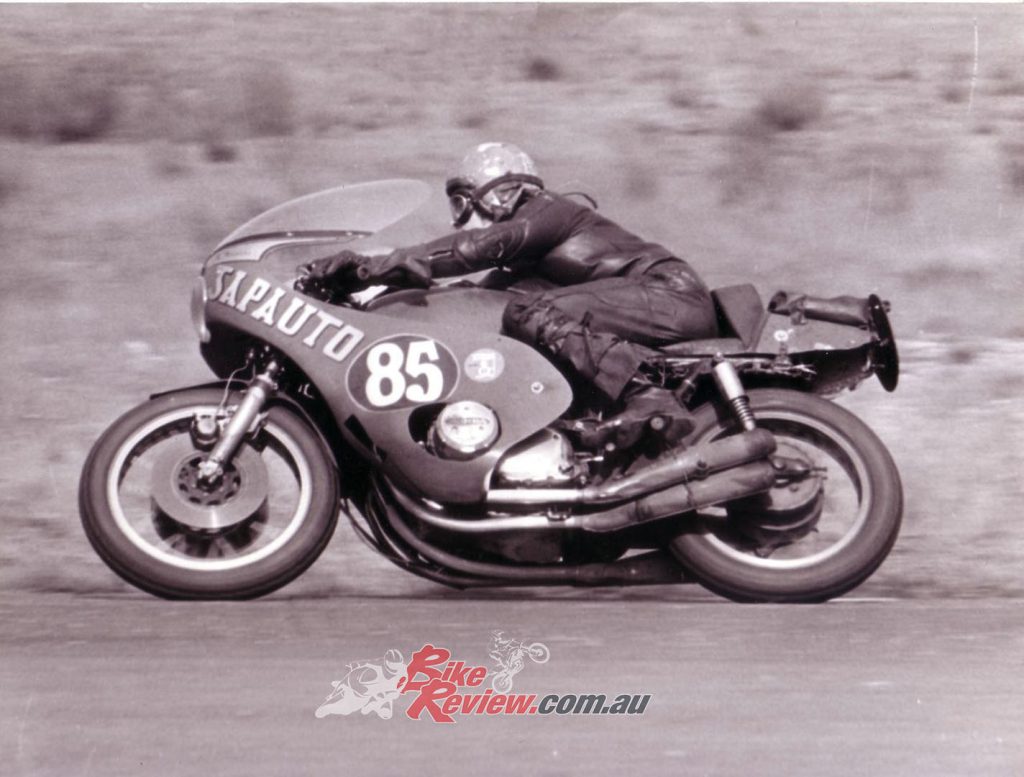

On that basis, taking part in Spain’s most prestigious annual race was a no-brainer, and Roger Ruiz and Christian Huguet must have pleased the local Japauto Owners Club by finishing second to the Godier/Genoud Kawasaki in the Montjuic marathon, on a new bike. This comprised the same essential 970cc motor which won the Bol d’Or the previous year fitted in a new PEM chassis that was basically a chrome-covered chrome-moly copy of the factory CR750 frame produced by Edouard Morena, wearing a modified version of the by now trademark Japauto bodywork, redesigned slightly to make it less cumbersome to ride.

A notable feature was the adoption for the Barcelona race of twin AP-Lockheed brake calipers gripping each of the twin front discs to provide extra bite for the several hard braking points on the city-centre circuit, in an early version of today’s four-piston designs. These were retained for the Bol d’Or, but the extra pair was later removed on the grounds that they added to the unsprung weight, and also made the steering heavier and rather ponderous. Japauto’s dependable duo of Ruiz/Huguet finished fifth in the Bol, although the previous year’s winner Thierry Tchernine, now teamed with Jean-Paul Boinet, retired from the race after just four hours after the team most untypically erred, and Boinet ran out of fuel on the far side of the circuit.

He can’t have been too pleased to have pushed the heavy Japauto halfway round the track back to the pits to refuel, only for Tchernine to pull in shortly after when it began to rain, saying that they were too far behind for it to be worth his while continuing! Vilaséca also lent a previous year’s Japauto chassis to JPX, in which they installed their own 970cc engine with heavily-finned cylinder block, for Denis Poulet/Pierre Soulas to finish 14th. But while used on their streetbikes, this component was never adopted on Japauto’s own racers – instead, from 1973 onwards they modified the stock Honda cylinder head by welding up the air passageways between the two outer cylinders, to reduce the risk of oil leaks and excessive oil consumption caused by the thin remaining metal wall between the paired bores.

For 1975 it was all change at Japauto, with Vilaséca using the profits generated in his Paris showroom to fund the construction of three new motorcycles, and mount a challenge for the newly revived five-round FIM Endurance Cup series. These comprised all-new PEM frames carrying specially-made multi-adjustable laydown DeCarbon twin shocks and modified Marzocchi cartridge forks off a Moto Guzzi, fitted with a redeveloped version of the Japauto 970cc engine now entirely built by JPX in Le Mans. Fitted with 31mm Keihin CR race carbs, a rebalanced, polished crank with racing conrods, 4-into-I Devil exhaust, and a ported, gas-flowed cylinder head with polished intake ports, plus Honda kit camshafts and five-speed gearbox, the new motor yielded 100hp@7,500rpm in a bike weighing 200kg dry, complete with twin headlamps, starter motor and alternator. The bodywork was also revamped.

For 1975 it was all change at Japauto, with Vilaséca using the profits generated in his Paris showroom to fund the construction of three new motorcycles.

Japauto’s season got off to a bad start when both bikes entered for the shakedown race at Le Mans in April retired. But the French team’s challenge for the FIM title started well, with Ruiz/Huguet third in the first round at Barcelona, although returnee Christian Bourgeois and new Italian recruit Guido Mandracci retired. But in the next round, the latter pairing had victory in sight in the Mugello 1000km, when the Italian crashed out of the race in the final half hour, leaving teammates Ruiz/Huguet to finish 7th – just ahead of the third Japauto ridden by Brits Gary Green and Dave Degens, the latter laying his welding torch aside to pick up his career as an Endurance racer again.

The Ruiz/Huguet duo swapped consistency for speed in the next round at Spa-Francorchamps, winning the Belgian 24-Hour race with Bourgeois/Mandracci in 6th place, to be tying on points for the series lead with Ducati rider Benjamin Grau, race-winner at the first two rounds, coming into the Bol d’Or. This was however a disaster for the three-bike Japauto team, with championship contenders Ruiz/Huguet sidelined after just 42 laps, after Ruiz burned out the clutch at the start and had to push the bike more than 4km to get back to the pits! Fixing it took 45min, but the team was forced to retire after four hours of the race. Bourgeois/Mandracci also pulled out after eight hours with irreparable rear end problems, leaving only the third bike of Sailler/Gaillard to finish 14th in a race won by the Godier/Genoud Kawasaki, ahead of two other green bikes.

Ruiz burned out the clutch at the start and had to push the bike more than 4km to get back to the pits.

But Japauto’s lead pairing of Ruiz/Huguet still led the points table coming into the final round in Britain, the Thruxton 400-Mile sprint race at the end of September, where by finishing 5th with teammates Green/Degens 7th, they were originally announced as having won the FIM Endurance title by scoring 36 points, three more than Godier/Genoud. Third at Thruxton, the Kawasaki duo had only scored points in three of the five rounds, against four out of five point-scoring finishes by the Japauto riders. But, the championship title was later awarded to the Kawasaki riders, on the grounds of the best three results out of five races counting, which meant the Japauto pair had to discard their Mugello result, winding up second in the series by just two points.

Bourgeois/Mandracci pulled out of the 1975 Bol d’Or after eight hours with irreparable rear end problems.

While this outcome – which took two weeks of discussions in smoke-filled rooms to ratify after the Thruxton round – inevitably left a bad taste, Christian Vilaséca was sporting enough to accept it, and continued to support the European Championship series even after Honda joined it officially in 1976 with the dohc 16-valve RCB 1000 racer, a more powerful 106bhp package than the single-cam 8-valve 100bhp-or-less 970cc Japauto. Four successive titles for Jean-Claude Chemarin on the RCB, three of them with Christian Léon, proved the worth of the Honda racer, and indeed for the 1976 Bol d’Or Honda supplied Japauto with a factory RCB motor for the bike ridden by Dave Croxford and Gary Green to 9th place, for which Morena built a special PEM frame wrapped in red Japauto bodywork.

After that, each year from 1977 onwards until 1983 Honda furnished Japauto with factory engines to install in its own PEM frames – first the RCB 1000, then the RSC 1100, before the arrival in 1984 of the 750cc TT F1 formula under which the races were run (race frame, production-based engine). Thereafter, Japauto stopped building its own bikes, just entering the French 24-hour events each year with a works RVF750R lent to them by the Honda factory, until 1989 when the curtain came down with a second-place finish in the Bol d’Or for reigning World Superbike champion Fred Merkel, teamed with Miguel Duhamel and Stephane Mertens on a factory RVF750R painted in Japauto’s distinctive red livery.

With costs spiralling for what was essentially a privateer dealer team competing against the full factory squads now contesting the World Endurance series, it was the end of a 20-year era during which a total of 72 different riders had competed in more than 100 races aboard Japauto machines entered by the Honda dealership in the shadow of the Arc de Triomphe.

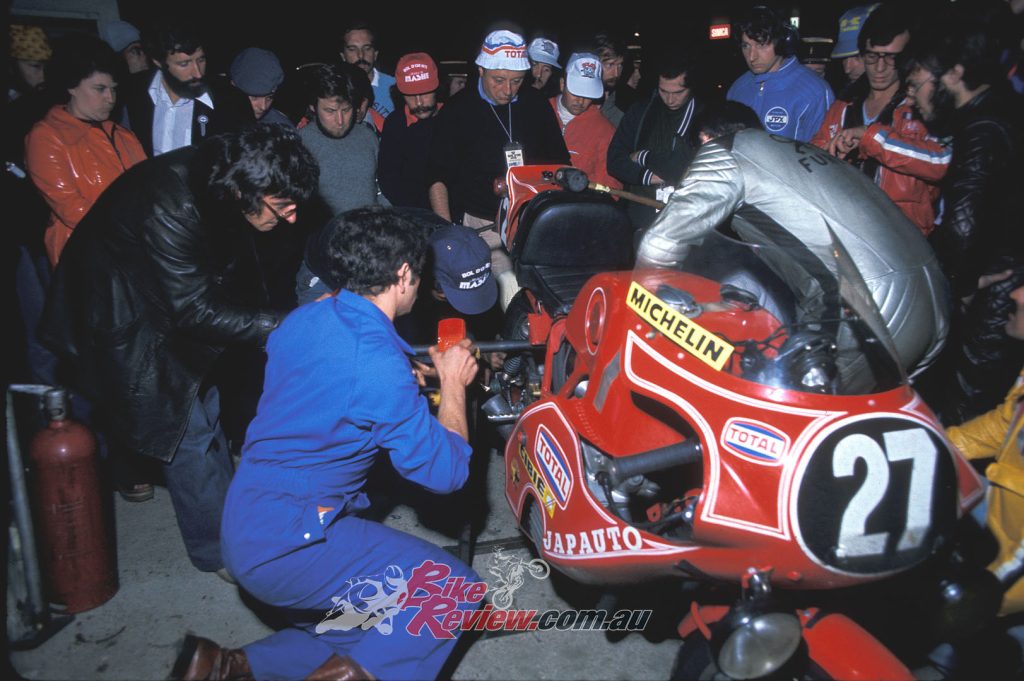

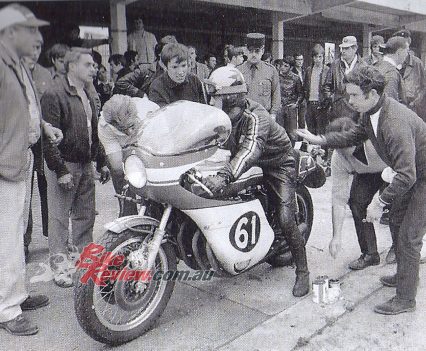

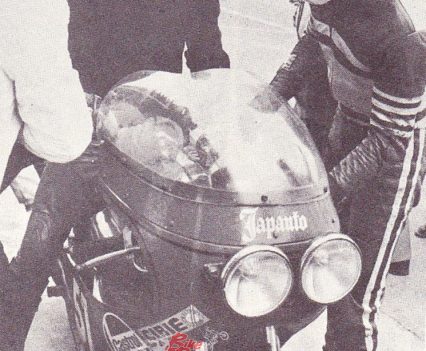

Michael Rougerie in the pits with Christian Vilaseca in 1969. Christian can be seen wearing his trademark hat.

Always wearing his trademark cap. Christian Vilaséca was invariably ever present in the Japauto pits during the Bol d’Or, frequently taking care of refuelling the bikes. It was doubly ironic, therefore, that he should suddenly pass away on the Sunday morning of the 1994 race, by which time Japauto was no longer taking part.

“Above all else, Japauto is a Honda dealer which has to attract customers to its doors. You must spend money on advertising to get them there, and I prefer to do this through Endurance racing.” – Christian Vilaséca

“Endurance racing is for me a justified passion,” Vilaséca was reported as saying in an interview before his death. “Above all else, Japauto is a Honda dealer which has to attract customers to its doors. You must spend money on advertising to get them there, and I prefer to do this through Endurance racing. But even if I wasn’t such a big fan of the sport, I’d still do it because it’s been an effective way of making our company very well known.” Don’t we all wish there were more like him today?!

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.

August 31, 2023

A few of us in the US knew about Japauto. I tried to import a 1000VX, but the complications were just monumental. We also knew about Godier/Genoud and their Kawasakis. It was a golden era that very few people knew about this side of the Atlantic.