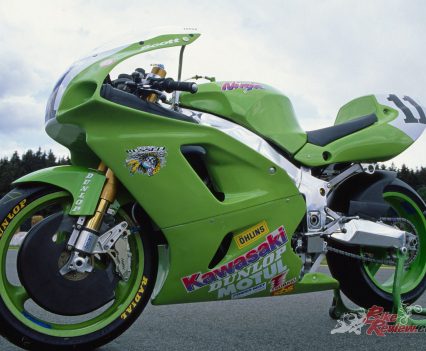

This Throwback Thursday we take a look at the Scott Russell Kawasaki ZXR750R World Superbike, also known as "The fastest carburetted four-stroke racebike ever built." Photos: Kel Edge.

It’s exactly 30 years since Kawasaki won Superbike’s World crown for the first time, courtesy of American Scott Russell, the cool-dude Georgian rider once memorably described as ‘so laid back, he’s practically horizontal’. We jumped on his WSBK ZXR750R from the year succeeding…

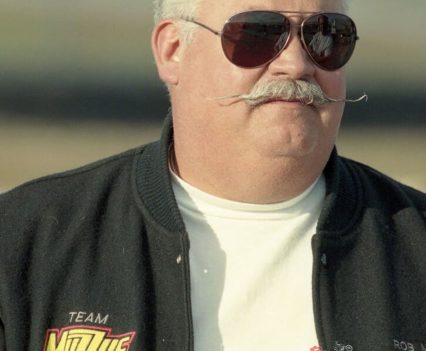

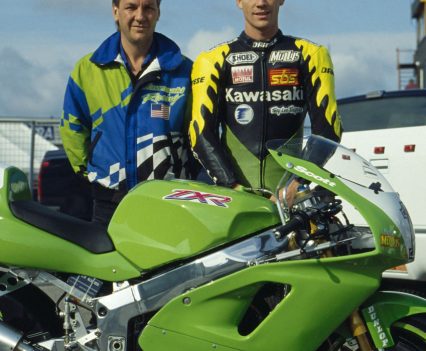

After winning the AMA Superbike title in 1992 with the Oregon-based Muzzy Kawasaki team, the 28-year old Russell made his full time debut on the world stage in 1993, the year when a shake-up in Kawasaki’s World Superbike effort saw his moustachioed team owner Rob Muzzy take charge of the hitherto Australian-run Japanese factory squad, whose rider Rob Phillis had finished third in the title chase in both 1991 and 1992 (and fourth in 1990).

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

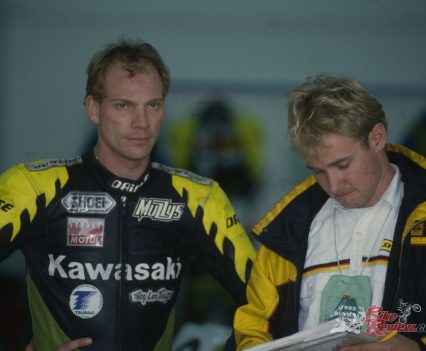

Muzzy sent Phillis back Down Under to compete in domestic racing for Kawasaki, and replaced him with Russell, with Phillis’s Aussie team boss Peter Doyle (today CEO of Motorcycling Australia) appointed manager of the new combined setup, and his Kiwi teammate Aaron Slight retained for a second successive season.

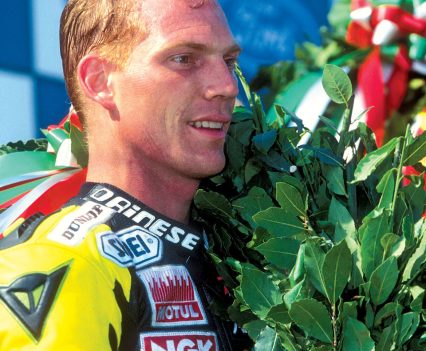

With further development on the ZXR750R delivering a bike which now clearly had the measure of the hitherto dominant Ducati desmo V-twins, the refocused Kawasaki effort achieved everything that could be expected of it by clinching Kawasaki’s first World Superbike crown, with Russell winning five of the 26 races eventually run. The final round in Mexico was cancelled with stray dogs already roaming the track, after a pick-up crossed the main straight right in front of Russell, who was flat out in sixth gear at the time!

The American thus clinched the title by 29 points from Ducati’s Carl Fogarty, the British rider who’d become his closest rival in his first season racing for the Italian factory team on a 926cc V-twin with a massive 20kg weight minimum advantage (145kg to 165kg) over the 750cc fours led by the Kawasaki. Fogarty won more than twice as many races as Russell – eleven, in total – but also crashed four times out of races to Russell’s once, and only twice finished second, to Scott’s amazing 12 runner-up places.

Greater consistency had won the American rider, and Kawasaki, their debut World Superbike series titles. As its contenders headed back from the abortive season-clinching shootout South of the Border, down Mexico way, there was a feeling – even among some Ducati fans – that it was Kawasaki’s turn to win four-stroke racing’s ultimate prize, and for the final time ever with a bike wearing carburettors. For after Honda’s return to the Superbike arena in 1994 with the fuel-injected RC45, and with Ducati already employing EFI, the rules of the game were changed for ever.

Yet it’s somehow appropriate that it should be Kawasaki that produced the ultimate four-cylinder UJM Superbike of the carburetted era, which stretched back over the previous quarter-century ever since Honda introduced the New Order with the debut of its iconic CB750. For it was Kawasaki that had shocked the bike world by pulling out of 500GP racing exactly a decade earlier, after some promising results with their avantgarde monocoque-framed KR500 in the hands of Kork Ballington and Gregg Hansford. The official reason, it says here on the ancient press release I still have in my files, was “to concentrate our company’s efforts on competing in future with motorcycles that are closely based on the models we sell to our customers for the street.”

The ZXR750, with four successive World Endurance titles from 1991-94 and that 1993 World Superbike crown all under its wheels, fulfilled that objective ideally – just as Tom Sykes’ ZX-10R did so exactly 20 years later in 2013, after Kawasaki management went back to the future again in 2008, exiting MotoGP racing to focus on developing an all-new Superbike contender for both the racetrack and the showroom. They haven’t been back since….

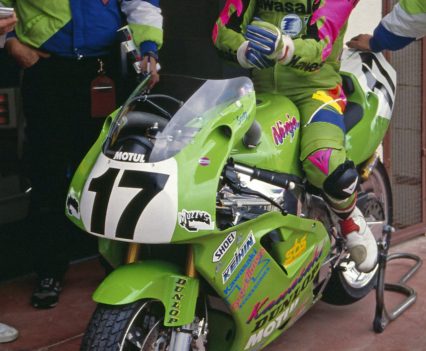

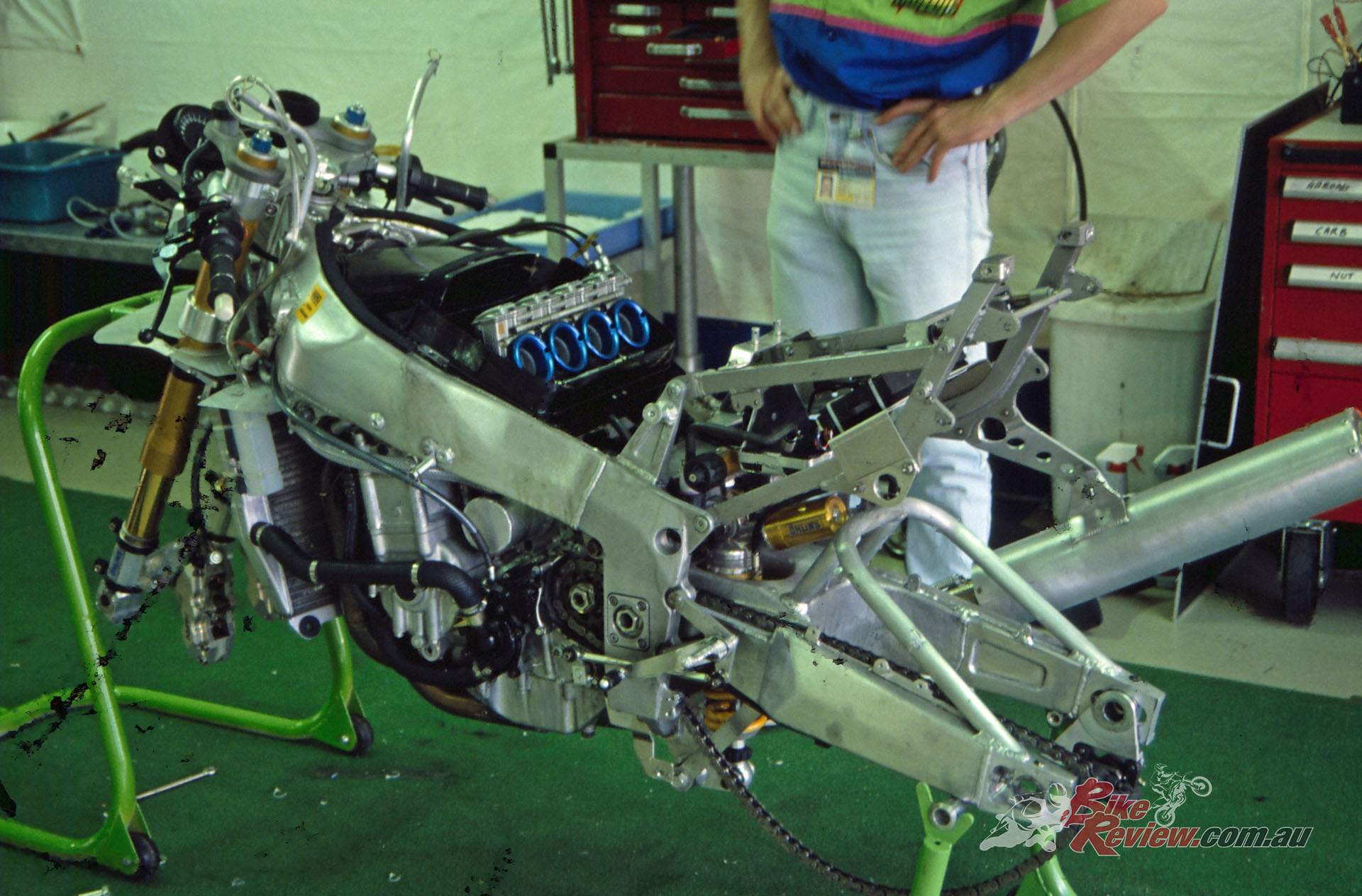

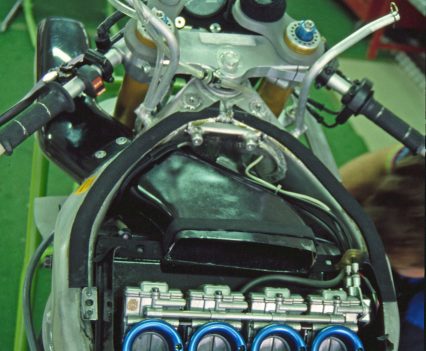

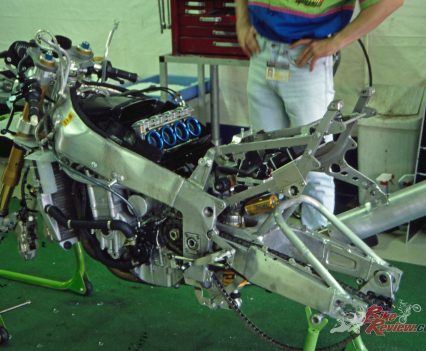

To win the 1993 World Superbike title, Kawasaki had come up with a new chassis for the ZXR750 closely based on its World Endurance title-winning ZXR-7 F1 bike, with an intake snorkel cut into the front left spar of the frame to feed air to the pressurised airbox enclosing the quartet of 39mm Keihin flatslide carbs. This was stiffer than the 1992 version thanks to increased wall thickness of the aluminium used for the main spars, as well as having a stiffer swingarm, with a cast section around the pivot area, which was now adjustable for location, same as on Phillis’s ’92 works bike.

Basically, Kawasaki took a leaf out of the Ducati book, and built an outright four-stroke GP bike that could be homologated for the street, improved according to their previous year’s racing experience – and thereby benefiting the guy who ultimately bankrolled all this, their streetbike customer in that pre-trackday era. The same applied to the engine, in spades: “There isn’t a single part in Scott Russell’s motor that you can’t buy from a Kawasaki dealer,” said Rob Muzzy. “Our motors are fitted with the ’93 ZXR customer race kit, which basically replicates the spec we ran the works bikes in last season. The trick is knowing how to put it all together, and set it up right!”

“There isn’t a single part in Scott Russell’s motor that you can’t buy from a Kawasaki dealer, “ said Rob Muzzy.

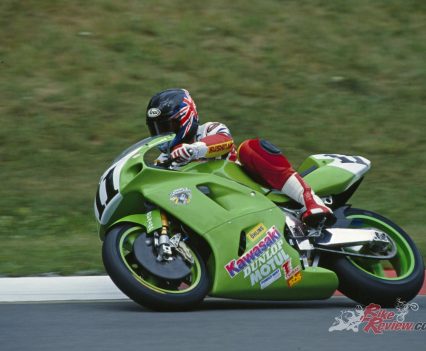

Judging by my 15 laps aboard Scott Russell’s racer at the fast, swoopy Zeltweg track in Austria, the Muzzy team certainly knew how to do that. By the standards of the era, this bike was intimidatingly fast, a breathtakingly powerful motorcycle that seemed more closely related to the GP world than its more street-derived, Rob Phillis-raced predecessor I’d tested at the same track exactly one year earlier.

“By the standards of the era, this bike was intimidatingly fast, a breathtakingly powerful motorcycle that seemed more closely related to the GP world than its more street-derived, Rob Phillis-raced predecessor.”

Part of this might have been due to the different riders’ different tastes in setup, but the rest surely came about from empirical development of an existing design that actually resulted in a radically different race bike in terms of both engine and chassis behaviour, compared to its forerunner.

Though very different from its Ducati rival in obvious ways, in fact the two were pretty similar beneath the skin – each explosively fast on acceleration by the standards of the era, dauntingly muscular, yet so quick and easy to steer into turns that you might think you were on a two-stroke 500GP bike. They both also stopped incredibly hard, too, with the hyper-effective carbon brakes then still permitted in Superbike racing, which compared to period metal brakes made you think you’d run into an invisible wall when you squeezed the front brake lever. Two means to accomplish the same objective, two benchmarks in four-stroke motorcycle evolution.

As Muzzy said, the WorldSBK bike wasn’t powered by any parts that you couldn’t buy for your own bike. With this, they still got 150hp@13,800rpm at the gearbox.

But only one winner. Although Ducati, with Giancarlo Falappa in the first half of the season, and Fogarty in the second, won more battles, it was Kawasaki that won the war. How so? “Basically, we refined our good points, took care of the bad ones and put a real good package together,” said Peter Doyle back in 1993, who later switched to manage Yoshimura Suzuki’s US race team that took Mat Mladin to a remarkable seven AMA Superbike titles from 1999 onwards.

“The major change was switching to Dunlop tyres, which Team Muzzy had run in the USA, but not for a full World Championship season. For those of us from the TKA team, it meant big changes in ride height and suspension setup coming from Michelins, and though the basic chassis geometry is the same, the setup has evolved from a year ago, as well as very different for each rider. Scott likes to powerslide the bike, so we use soft rear shock settings for him, whereas Aaron doesn’t like the wide, sweeping cornering style; he brakes deep into the apex, squares it off and powers out, so we need a stiffer rear end for him. The fact that the chassis can be adapted to suit either rider’s style shows it’s basically very good.”

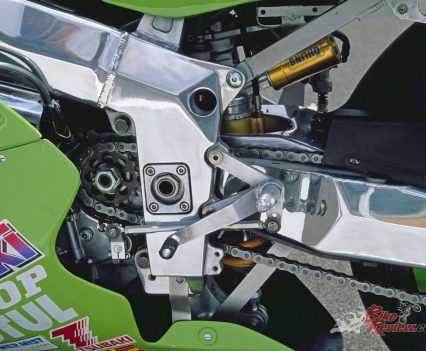

A multi-adjustable streetbike chassis was an inevitable spinoff from Superbike racing, but in fact while the team did experiment a little with the adjustable swingarm pivot, Doyle admitted they usually came back to the original settings. More likely to be altered from one circuit to another was the rising rate link on the rear Öhlins shock, which could be changed by fitting a different one of the several different links the team had developed. “Basically, we’ve been looking for traction,” said Doyle, “to get it to drive better out of turns and, when it does start sliding, to do so controllably.”

“A multi-adjustable streetbike chassis was an inevitable spinoff from Superbike racing, but in fact while the team did experiment a little with the adjustable swingarm pivot, Doyle admitted they usually came back to the original settings.”

Yes, but this also meant that tyre choice for a meaty, powerful (150 bhp up 5 bhp from ’92), heavy (166kg, right on the 165kg Superbike weight limit), wheel-spinning megabike like this was critical, especially on a tight track with many slow turns. Guess right and you might win, but guess wrong – you lose! Having lived with the ZXR750 for what by then was some years, and come to understand it so well, both Russell and Slight had a head start at getting it right, with the help of Dunlop’s technicians, but Scott still wasn’t happy with the tyres available in the first part of the season, until Dunlop’s R&D started to get on top of the problem.

“I knew they’d changed the setup a lot from the previous year’s Phillis bike I’d ridden, but I wasn’t expecting to find a 500GP racer masquerading as a Superbike!”

I had to get on top of another kind of problem at Zeltweg: how to stay in charge of a bike that at first felt disturbingly unstable in a straight line, downright twitchy laying into a turn, and insisted on reaching for the stars powering out of Zeltweg’s only slowish corner, the Chicane. I knew they’d changed the setup a lot from the previous year’s Phillis bike I’d ridden, but I wasn’t expecting to find a 500GP racer masquerading as a Superbike!

Cathcart took the ZXR750R for a spin at Zeltweg. The wild machine refusing to stay steady in a straight line!

For a start, the riding position was different, because on the new ’93 frame the fuel tank was shorter and wider, moving the your body weight forward to load up the front end, at the expense of a sense of increased bulk. The new-type ultra-trick (and ultra-costly) 46mm Öhlins fork, gold-plated not because of its price tag, but because of its then-novel titanium oxide coating aimed at reducing friction and wear, as well as eliminating stone damage, were set at the same 24.5º head angle as the stock roadbike frame, but this a had been effectively steepened by substantially raising the rear ride height.

At the same time, greater fork offsets were employed to reduce the trail from 1992’s kicked out 108mm to a quicker-steering 102mm. Combined with the narrow head angle and accentuated front end weight bias (up to 55/45 on Russell’s bike, compared to 52/45 on Phillis’s) this delivered a bike that took quite a bit of coming to terms with.

“It was definitely intimidating, at first, until I eventually figured out that everything is done for a purpose, and the only way to make the Kawasaki respond was to get on top of it, and show it who’s in charge.”

It was definitely intimidating, at first, until I eventually figured out that everything is done for a purpose, and the only way to make the Kawasaki respond was to get on top of it, and show it who’s in charge. This was a bike that had needed to be ridden very forcefully – even a first-generation Ducati 851 was much less physical to change direction aboard, by comparison – but which delivered the goods if you did so. I’m no Superbike superman, but the 1:57 lap which the watching former two-time World Superbike champion Fred Merkel’s watch had me lapping Zeltweg on aboard the Russell ZXR would have been good enough for the top 30 in qualifying for the World Superbike round the day before – some indication of its miraculous powers!

“This was a bike that had needed to be ridden very forcefully – even a first-generation Ducati 851 was much less physical to change direction aboard.”

This only happened after I convinced myself that it was safe to ignore those speed wobbles up the hill from the chicane, if I hit one of the bumps in the track at speed, and that at my speeds compared to Scott’s, the front wheel chatter over the ripples on the off-camber downhill left-hander after the Bosch Kurve, wasn’t anything to get nervous about. Mr. Russell hisself was watching from that very spot, having cycled up the hill on his brand-new tricked-cut Trek mountain bike.

“”The 1:57 lap which Fred Merkel’s watch had me lapping Zeltweg on aboard the Russell ZXR would have been good enough for the top 30 in qualifying for the World Superbike round the day before.”

“Yeah, same thing happened to me in the dry there,” he consoled. “Maybe a suspension problem, or it could of been the tyre – either one. But those new Öhlins forks work really smooth most anywhere else, plus they’re that stiffer, being thicker than the old ones, that they work real good under the new brakes that we have this year.”

Ah yes, Scott – the brakes: thanks for reminding me. And what brakes: personal milestone time – simply the best, up to that point. I’d never ridden a bike, not even the factory 500GP racers that I was by then quite used to riding, with such absolutely mind-blowing stopping power as the Muzzy Kawasaki Superbike had with the then-latest 310mm Nissin carbon discs, and the new six-piston Nissin calipers. At that stage these were definitely the best brakes I’d ever used on a motorcycle, which would allow the ZXR to sit it out into turns with a 20kg lighter Ducati V-twin, yet still had remarkable sensitivity.

“At that stage these were definitely the best brakes I’d ever used on a motorcycle, which would allow the ZXR to sit it out into turns with a 20kg lighter Ducati V-twin, yet still had remarkable sensitivity.”

Allowing you to caress the lever – like with metal discs – to knock off a little corner speed if you entered a turn too enthusiastically, or needed to change line to avoid a slower bike. It was noticeable that unlike most other users of black brakes, the Muzzy Kawasakis always ran shrouds on both slow tracks as well as fast, in hot weather same as cool, presumably ensuring a constant braking performance, with no element of fluctuation – think of it as a still air box, but for brakes! Scott would set the lever close to the ‘bar at rest, but then as you heated the brakes up the first half lap – if necessary with a finger resting lightly on the lever in a straight line – the lever fattened out and then stayed there, without any of the variable servo-type effect of most other carbon systems of the time, which got more sensitive, and gripped harder and faster, as they heated up. And though the six-pot Nissin calipers gave a fierce bite when needed, they also had that low-pressure sensitivity, perhaps because of each caliper’s differential piston sizes. The best.

“Though the six-pot Nissin calipers gave a fierce bite when needed, they also had that low-pressure sensitivity, perhaps because of each caliper’s differential piston sizes.”

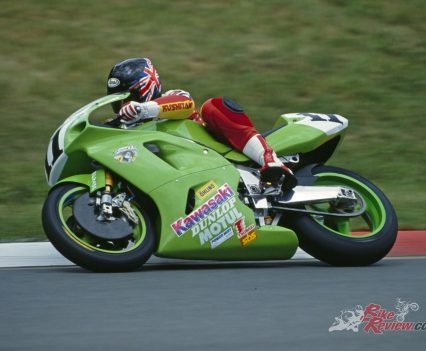

Although the new Öhlins fork allowed you to brake quite hard on the angle, I ended up carrying quite a lot of corner speed into some of the turns. That’s where the Muzzy ZXR’s geometry started to tell: instead of the more ponderous steering of the Phillis ‘92 bike, which even in improved form the previous season was a lot more of an effort to lift from side to side in the Zeltweg chicane, Russell’s World champion Kawasaki changed direction extremely well for a big in-line four.

Yet once you got used to the change in geometry, it wasn’t actually as radical to ride as it seemed at first, letting you take wide, sweeping lines through Zeltweg’s fast curves without the front wheel feeling it wanted to tuck under. Hit a bump on the angle, and it did start to shake its head a little sometimes, probably a function of having quite a lot of weight up high. But generally the steering felt neutral, and notably lighter than before – the carbon brakes would have played a role here, with their substantially reduced gyroscopic weight helping to speed up the steering. And the extra weight on the front wheel helped maximise grip as you turn into a corner – at a price that you then paid on the exit.

For even I, at my reduced pace, indeed found that the ZXR liked to spin the tyre in those pre-TC days and play tunes on the exhaust note as you switched on the power exiting the Zeltweg chicane. At first I thought this and the speed wobble that sometimes appeared up the next sort-of straight might be due to the suspension being too soft for my extra weight. But it turned out I was only a couple of kilos heavier than Scott, so that wasn’t the reason. Fact is, this was just an extremely potent, accelerative motorcycle that motored out of turns like it had been fired from a rocket-launcher, and getting a tyre and suspension setup to cope was a constant challenge. I know for sure that riding it certainly was – and tiring mentally, too, as well as physically. Scott Russell had to be a very fit guy to win races on it – and Aaron Slight, too. Interesting, by the way, that the Muzzy team used a wide 6.25 in. rear wheel, whereas the previous season Phillis had found that using a smaller 5.75 in. rim for the same size tyre (but a Michelin, of course) gave better traction.

“For even I, at my reduced pace, indeed found that the ZXR liked to spin the tyre in those pre-TC days and play tunes on the exhaust note as you switched on the power exiting the Zeltweg chicane.”

The guilty party in all this was that so-potent Muzzy motor, which nevertheless had a more linear power delivery from 8,000rpm upwards than before, while revving even harder and more freely than the previous year’s bike had done. That encouraged you to attack the hard 14,200rpm rev-limiter as a matter of course, and though there wasn’t the kick in the power delivery there used to be from about 12,000rpm up, the constant build of power up to the 13,800 rpm peak meant you had to try to keep it revving hard all the time.

That meant using the gearbox a lot – the previously Kawasaki’s weakest point, but fortunately completely altered for 1993: “There’s not one part the same on the gear cluster,” said Peter Doyle, “and it’s all better quality, too, with a different shift drum and detent spring as well. We’ve seen an end to our gearbox problems from last season.” And me to mine, for unlike the previous year on the Phillis bike, when I’d given the revlimiter a good workout thanks to the iffy gearshift, I didn’t miss a single gear in my 15 laps on the Russell Kawasaki, and the shift action was definitely sharper and more precise. No new-gen powershifter when I rode the bike, though, and being such an easy-revving motor, I’m sure it would have benefited from one. That must surely have been on the wishlist for the future, but in the meantime you could now change up clutchlessly, unlike the previous year on the Phillis bike. It was a bit of a miracle Robbie did so well on it!

Yet the power that the 1993 World Superbike champion machine delivered was available to any other Kawasaki team, according to Peter Doyle: “We use the same parts as last year, which have now become the ’93 racer kit,” he insisted. “So that means forged race pistons, 2.5mm longer conrods, a close-ratio gearbox, and the kit ignition, which still isn’t programmable, though. We use a Muzzy pipe which delivers more top end power (4 bhp from 12,000 rpm upwards, at the expense of the same amount off the bottom end – AC), and that’s about it.”

Yes, apart from the porting and flowing of the cylinder head carried out at Muzzy Racing HQ in Bend, Oregon, the constant experimentation with inlet lengths, carb settings, cam timing and exhaust pipe design in pursuit not only of more power, but also a different power curve – all the sort of work very few private teams ever had the time, the facilities or the budget to accomplish. But thanks to the Kawasaki factory, this one did – and Scott Russell’s World Superbike title was the reward.

“No doubt about it: you had to marvel at what the Muzzy Kawasaki ZXR750R represented. It was the fastest and most potent four-stroke racebike ever built fitted with carburettors.”

No doubt about it: you had to marvel at what the Muzzy Kawasaki ZXR750R represented. It was the fastest and most potent four-stroke racebike ever built fitted with carburettors. Refined into a title-winning Superbike with the manners of a GP racer, it was ridden to deserved World Championship success by the man who proved its master, as well as that of the Ducati mafia – Scott Russell.

In doing so, Scott proved that green was the colour of the 1993 World Superbike season, a year in which the old axiom that to finish first, you must first finish, was never truer. The title-winning Muzzy Kawasaki was fast, reliable and finally handled like a true racer, not a converted streetbike, and in doing so it became the Ultimate Racer of the first generation of four-cylinder Superbikes – the ones that wore carbs, not injectors…..

Scott Russell World Superbike Kawasaki ZXR750R Specifications

ENGINE: Watercooled dohc four-cylinder four-stroke with four valves per cylinder and offset chain camshaft drive, 749cc, 71 x 47.3mm bore x stroke, 4 x 39mm Keihin flatslides, Digital electronic CDI (non-programmable), Multiplate wet clutch, 6-speed.

CHASSIS: Aluminium twin-spar frame, 46mm Öhlins inverted telescopic fork (f) Fabricated aluminium swingarm with adjustable pivot, rising rate linkage and Öhlins shock (r) 2 x 310mm Nissin carbon discs with six-piston Nissin calipers (f) 200mm Nissin steel disc with two-piston Nissin caliper (R) 125/65-17 Dunlop KR1O6 radial on 3.75 in. Marchesini wheel (F) 185/55-17 Dunlop KR108 radial on 6.25 in. Marchesini wheel (r). 1410mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 150hp@13,800rpm (at gearbox), 289km/h top speed (Hockenheim), 166 kg with oil/water, no fuel, split 55/45.

Owner: Team Muzzy Kawasaki, Bend, Oregon, USA.

1993 World Superbike Kawasaki ZXR750R Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.