The Bear heads to the Pinnacles in WA and tells us all about it. While there, he does his best to convince a Japanese motorcycle tourist to head to them for a look. It was a fail... His loss!

You see them every now and then in Australia, mostly in remote places. I suppose they stand out more if there is nothing much in the background. They are young Japanese riders on dirt bikes, almost always Hondas and invariably loaded to the gunwales…

I have sometimes suspected that Japan has discovered the secret of simply sticking more canisters, bags and boxes to the existing load of the bike without needing to tie them on. Super hook-and-loop? I shall never know. The riders are invariably cheerful, keen to communicate but utterly unable to speak more than three or four words of English.

That is not a criticism; I can’t count the number of countries in which I have found myself with my bike and no more than three or four words of the local language. As for Japanese, I know exactly one: “hai”, which I take to mean “yes”. Oh, wait, “katana” which means either a sword or a silver Suzuki. Japanese, I am told by a friend who learned to speak it fluently, is a difficult language.

As for these blokes and women on dirt bikes, someone once explained to me that riding a motorcycle to remote places in Australia is a rite of passage for some young Japanese people. There are guidebooks which tell them how to do this.

Check out our interview here with BikeReview’s own Eri Taguchi, who toured all of Australia solo, including the red centre, on a little BMW G 310 R…

One particular meeting with one of these solo riders was outside the small supermarket in Cervantes, a town in Western Australia named after a ship wrecked nearby which had been named after the man who wrote Don Quixote. Showing odd but laudable respect for the shipwreck, most of the streets in Cervantes have been given Spanish names.

I tried to explain to this chap that quite remarkable landforms — the Pinnacles– were only a few kilometres away to the south, and thought that with gestures and pictures in a brochure had managed to get the idea across. He nodded a great deal, as did I, and seemed keen to visit these remarkable monoliths. Still nodding respectfully, he rode off in the wrong direction. My gesturing had clearly not been up to the task.

“My gesturing had clearly not been up to the task”…

The Pinnacles, a mere 250km north of Perth and therefore a good day trip, are well worth a visit. The $15 it costs these days is money well spent. They are limestone monoliths ranging in height between 10cm (three or four inches) and 5 metres (16 or 17 feet), and nobody is quite sure how they formed.

One theory (pay attention now) suggests that they were formed as dissolutional remnants of the Tamala Limestone, i.e. that they formed as a result of a period of extensive solutional weathering (karstification, to be precise). The focused solution initially formed small solutional depressions, mainly solution pipes, which were progressively enlarged over time, resulting in the pinnacle topography. Some pinnacles represent cemented void infills (microbialites and/or re-deposited sand), which are more resistant to erosion, but dissolution still played the final role in pinnacle development. Good, eh?

A second theory states that they were formed through the preservation of tree casts buried in coastal aeolianites, where roots became groundwater conduits, resulting in the precipitation of indurated (hard) calcrete. Subsequent wind erosion of the aeolianite then exposed the calcrete pillars. Could be, could be but seems unlikely to me.

A third proposal suggests that plants played an active role in the creation of the Pinnacles, based on the mechanism that formed smaller “root casts” in other parts of the world. As transpiration drew water through the soil to the roots, nutrients and other dissolved minerals flowed toward the root—a process termed “mass-flow”, that can result in the accumulation of nutrients at the surface of the root. In coastal aeolian sands that consist of large amounts of calcium (derived from marine shells), the movement of water to the roots would drive the flow of calcium to the root surface. This calcium accumulates and when the roots die, the space they occupied is subsequently also filled. Well, you never know. Or at least I never know.

The Pinnacles and Nambung National Park in which you will find them form one of Western Australia’s iconic landscapes. They are roughly 200km north of Perth along a pleasant coastal road. The first mention of the Pinnacles dates back to the 1650s, when Dutch sailors on passing ships mistook them for a city. They were disabused of this when they explored the North and South Hummocks and found no use for them. The Pinnacles Desert was included in Nambung National Park in the 1960s and became a popular destination which now allegedly sees thousands of visitors per year. Oddly enough, whenever I’ve been there it’s been deserted. No pun intended. Well, not much.

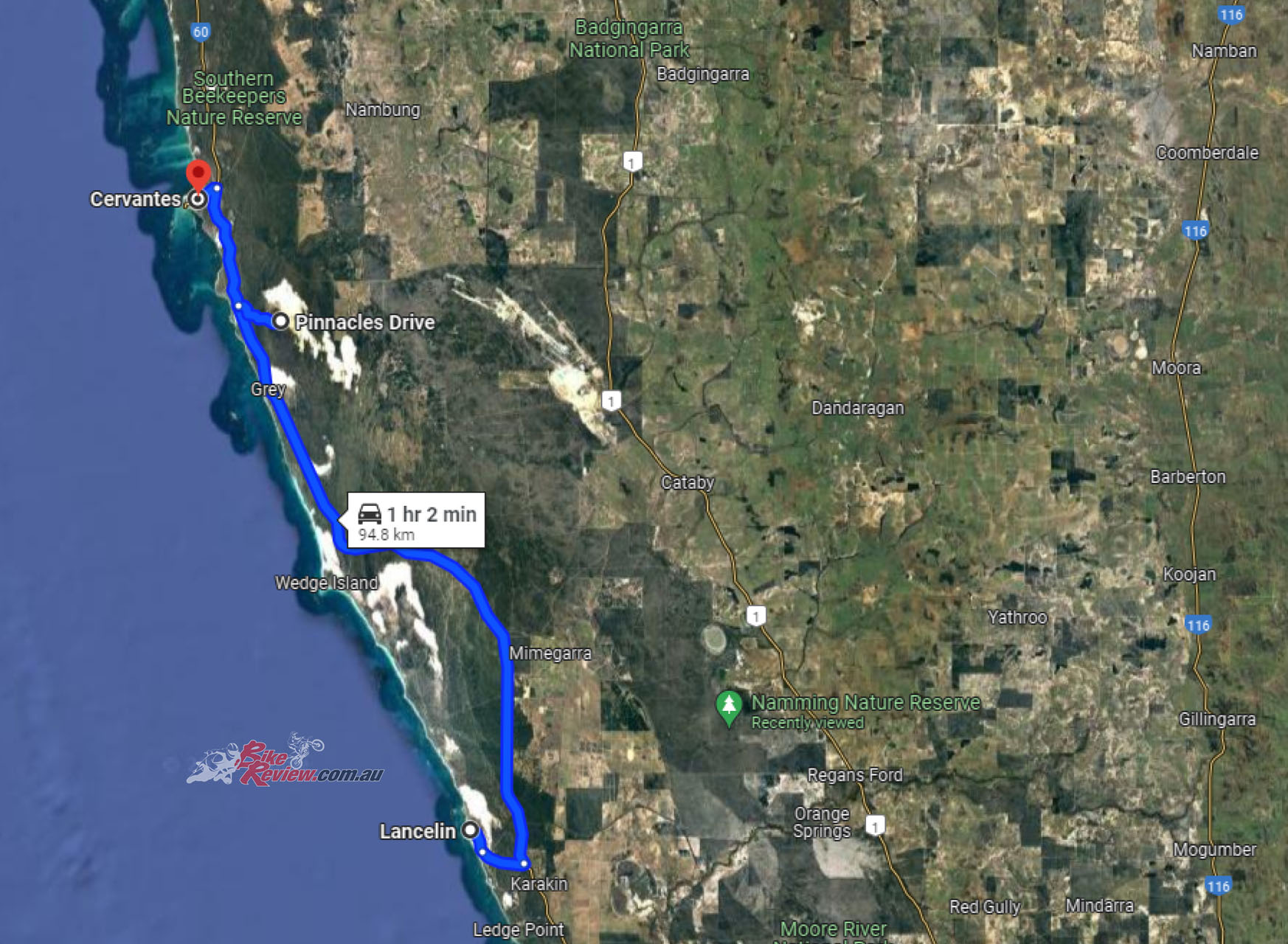

The road leading to the Pinnacles Desert Discovery Centre from Cervantes in the north and Lancelin in the south is sealed, and although the tracks in the Pinnacles themselves are sand, they have a fairly solid base and are not difficult on a bike. I have heard that vehicle access may be banned; I hope not. The Centre allows you to discover the natural and cultural heritage values this area holds. The Pinnacles Desert has been home to blackfellas for many years – artifacts dating back 6000 years have been found and identified by whitefellas. The association of blackfellas with the desert probably goes back much further than that. It has appeared in Aboriginal Dreamtime for many generations.

Both Lancelin and Cervantes have accommodation at various levels, and Cervantes has the additional attraction of being a lobster (really crayfish) fishing town. The crustaceans are not a lot cheaper than they are elsewhere, but they are guaranteed fresh. And the beer’s always cold.