Back to the futuro | This is what happens when you get your car division to design a motorcycle. The BMW futuro, released to the world at Cologne in 1980... Words & Photos: The Bear

There was more than one time when we nearly lost BMW motorcycles. In the 1970s, the board was beginning to despair of the future of its by now minor division. Bikes had been what kept the company going in the ‘20s when they weren’t able to build aviation engines.

Aircraft engines were BMW’s first specialty, but 50 years later bike sales were down and continuing to fall. The fact that this was BMW’s own fault hadn’t penetrated. It would take Hans Muth to revive the marque with his design of the beautiful R 90 S, but he wasn’t the only one who worked on the salvation of the bike division. The R 90 S was the successful one, but it wasn’t alone. Another even more ambitious project did not do so well. We should probably be grateful to the gods of the road for that.

Read Pete’s previous Bear Tracks columns here…

In the summer of 1979, the company board decided that BMW needed to show that its horizontally opposed twin with shaft drive was not, as many people were saying, a tired relic. They also wanted to put the Japanese on the back foot by doing something novel very quickly. But they didn’t trust the motorcycle division with the project. The press release noted that the bike people “had more than enough to do in Munich with current development work (and maybe because they were a little scared of in-firm nearsightedness, which they did not want to risk)”.

Yes, believe it or not that was spelled out in the press kit that was released when the resulting study, the ‘futuro’, was shown at the Cologne Motorcycle Show in 1980. You don’t see that kind of naked honesty these days.

“Predictably enough, they created what looked like a two-wheeled car”…

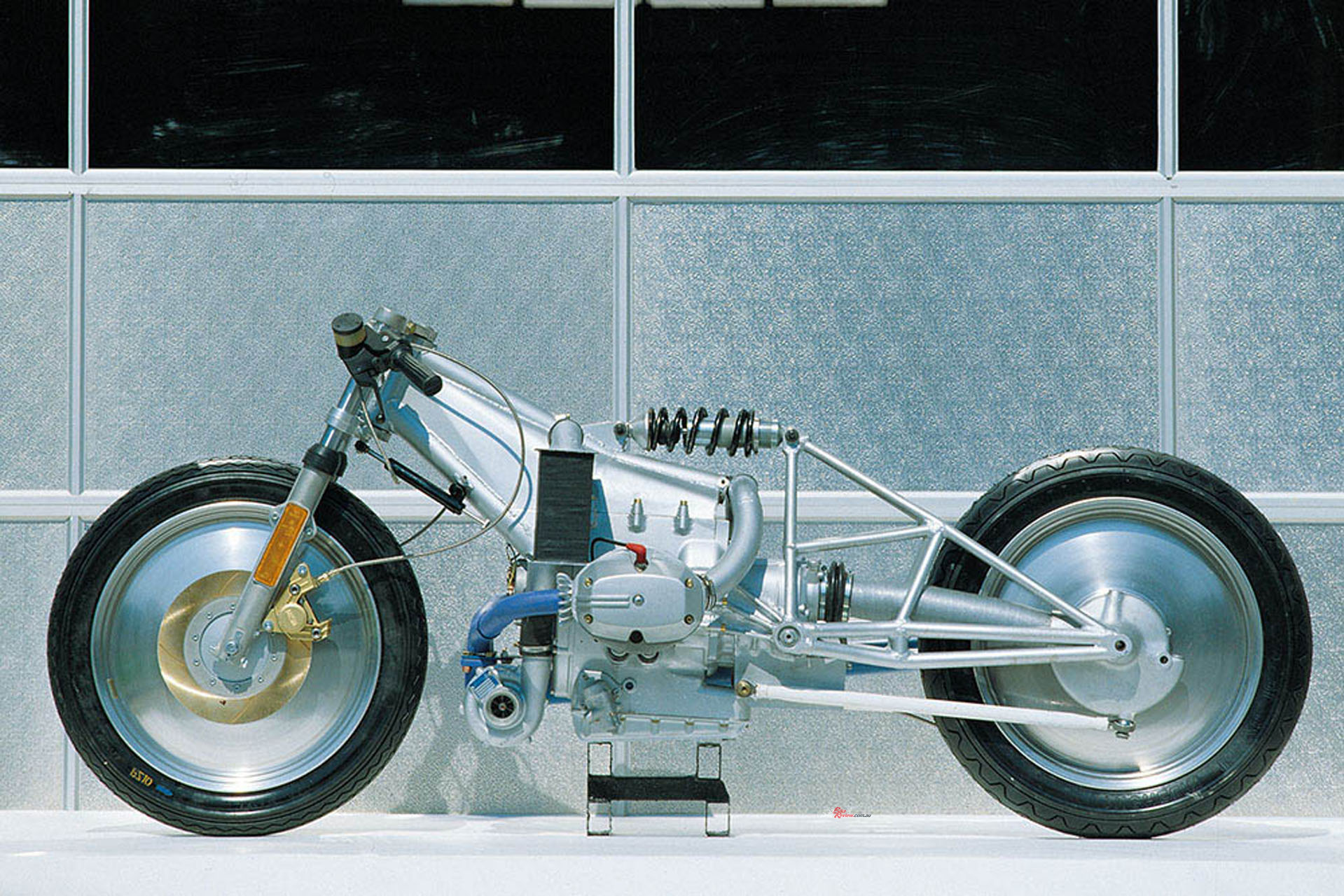

But perhaps those words reflected the tension between different sections of BMW; the motorcycle division was not yet ‘BMW Motorrad’ with its own board, but just a part of the mother company. As a result, the job went to a car specialist. Nobody seems really sure why, but the contract to develop the futuro study went to a Frankfurt firm which had had never had anything to do with motorcycles, b&b (lower case was, er, big in those days). They had mostly produced things like modifications for Porsches and electronic dashboards for the VW Rabbit. Predictably enough, they created what looked like a two-wheeled car.

The b&b development engineer responsible, Eberhard Schulz, was one of the people who had never worked on a motorcycle before. He had carte blanche, however, being told to come up with a design “completely regardless of current technical feasibility”. He also had at call the skills of people like former BMW director and “motorcycle whisperer” Helmut Boensch, engine specialists Dr Schrick, experts from the Batelle Institute and others from TüV. Oddly enough, despite his brief to go sci-fi, he came up with a technically perfectly feasible vehicle. An expensive one, it’s true, but not an impossible one.

“One thing is certain: the typical BMW qualities of today will still not be yesterday’s tomorrow.” Err… Huh?

BMW had learned from the development of Hans Muth’s R 100 RS that optimising aerodynamics could make a huge difference to performance, and that lesson was applied to the futuro along with drastically reduced weight of 180kg. Aluminium, carbon-fibre-reinforced plastic, Titanium and Kevlar were incorporated in the bike, but apart from the cantilever rear suspension and sintered brake discs (not entirely new) there was not really much new technology. Well, apart from the VW Rabbit-like dash.

It’s difficult to understand why b&b went for a turbocharger for the 800cc boxer engine. The stated intention was to improve low and midrange performance, something that a supercharger does much better – and BMW had substantial experience with superchargers on its race bikes. Perhaps it was the knowledge that the Japanese were working on turbocharging bikes that convinced b&b to do the same.

The turbo made the exceptionally light bike quite quick, and possibly as a way of diverting criticism from a motorcycle that could reach well over 200km/h, BMW and b&b described the futuro as a “safety design”. Various bits of it, including the disc wheels, were intended as crumple zones and the seating position was set up so that the rider would be propelled over the obstacle in case of a crash. There was even a suit designed to be worn with the bike which had airbags built into it.

The press release concludes rather gnomically that “One thing is certain: the typical BMW qualities of today will still not be yesterday’s tomorrow.”

The Cologne show must have provided sweet revenge for designer Hans Muth. Stymied again and again at BMW, he had had to go to Suzuki to realise his most dramatic dream – the Katana. It debuted at the same show as the futuro and, along with Honda’s CX Turbo sucked up all the oxygen in the show’s halls. The futuristic BMW was little noticed. As for getting ahead of the Japanese, the futuro was a design study which BMW itself acknowledged would never be built as such – while Honda’s Turbo was already a production model.

BMW took the muted reception of the futuro rather badly, and the prototype disappeared from public view and from the company’s collective memory. When I asked for some information about it few years ago, nobody claimed to know anything about it. In fact, it looked to me as if some of the futuro’s design ideas had resurfaced in the K 1, without acknowledgement.

But the Bavarians are not like the Japanese. Where the latter have a history of simply losing prototypes, even the ones of highly successful models like Honda’s GoldWing, BMW loses nothing. The futuro vegetated for several decades in storage with BMW Classic, but has recently experienced a revival and even seen the light of day at international motorcycle shows.

I can’t help but wonder what would have happened to BMW’s motorcycle division if it had been the futuro rather than the R 90 S that got the go-ahead.