Weighing 283kg, with 190hp and 203Nm, this monster Indian Challenger King of the Baggers factory racer, ridden by Troy Herfoss, can match a Moto3 Lap Time! Cathcart finds out how...

Down the years I’ve been privileged to track-test a vast array of different road racers, from dozens of factory MotoGP and 500GP bikes, through countless World Superbike contenders, to numerous ProTwin musclebikes (AC tests are here), home or factory built.

But nothing – literally, nothing!! – I’ve ever ridden before compared in terms of its sheer improbability coupled with its mammoth size, hefty weight, improbable performance and downright belligerence with the factory Indian Challenger which reigning three-time ASBK Superbike and Supersport 600 champion Troy Herfoss is racing this year in the MotoAmerica King of the Baggers series, alongside 2022 KOTB champion Tyler O’Hara.

But nothing – literally, nothing!! – I’ve ever ridden before compared in terms of its sheer improbability coupled with its mammoth size, hefty weight, improbable performance and downright belligerence with the factory Indian Challenger which reigning three-time ASBK Superbike and Supersport 600 champion Troy Herfoss is racing this year in the MotoAmerica King of the Baggers series, alongside 2022 KOTB champion Tyler O’Hara.

Saturday COTA and Herfoss had just qualified third and then won the KOTB $5000 Challenge Race, more to come…

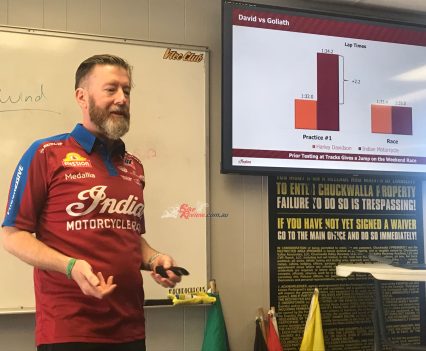

And doing all right, too – as in qualifying on pole for the season-opening Daytona double-header on March 8-9, Troy’s first ever race on this ultra-extreme motorcycle, and on his debut ride on the Florida Speedway’s steep 31° bankings, too. This guy’s a fast learner! Running at speeds topping 185mph Herfoss stunned the Yanks by earning a trio of runner-up finishes on his Indian Challenger. The first of these came in the Challenge race, a short sprint contest prior to the formal KOTB title events, in which he fended off countless attacks by his Harley-Davidson rivals headed by 2021 champion Kyle Wyman to follow his victorious Indian teammate and former 2022 champion Tyler O’Hara over the line.

Read Troy Herfoss’s interview after his Saturday COTA KOTB Challenge Race Victory here.

Race 1 saw a grandstand finish, with Wyman edging Herfoss by just 0.018 sec., but in Race 2 Herfoss demonstrated his talent by leading into the final lap, before he overshot the back straight chicane and opened the door for Wyman, who sprinted to victory by 0.137 second over the Aussie. The two were now ten points apart in the standings for the 16-race series, with the next race the Baggers’ most illustrious gig yet, as support class to the American MotoGP round at Circuit of the Americas in Austin, Texas, on April 12-14 this weekend. [Update – Herfoss has qualified third and then won the KOTB $5000 Challenge Race, and Race One, and more to come – Ed].

Troy Herfoss (17) leads Hayden Gillim (1), Bobby Fong (50) and Kyle Wyman (33) en route to winning the Mission King Of The Baggers Challenge on Friday at Circuit of The Americas. Photo by Brian J. Nelson

The King of the Baggers series has reignited the century-plus on-track warfare between America’s two leading manufacturers. For Indian vs. Harley is the oldest brand rivalry in motorcycle sport, which after Harley-Davidson finally went racing properly in 1917 blazed into life over the next four decades, then remained dormant for several more after Indian’s corporate demise first time around in 1953.

Until now, hostilities were confined to doing it on the dirt – or on the Murderdrome board tracks of last century’s nineteen-teens. But after Indian was purchased in 2011 by Polaris Corp. and relaunched as a major manufacturer, it returned to America’s dirt oval race tracks in 2016 with the FTR750, which has since made the AFT series its own in a comparable way to Harley’s previous four decades of dirt track dominance with the XR750.

Until now, hostilities were confined to doing it on the dirt – or on the Murderdrome board tracks of last century’s nineteen-teens.

But in the past four years that rivalry has now been extended to what used to be called pavement racing back in the day, as America’s two oldest bike brands have fought each other to earn bragging rights to road racing’s King of the Baggers/KOTB crown, in the ultra-improbable but potentially very lucrative pursuit of going racing with tuned-up versions of their best-selling V-twin streetbike models supplied new with twin chassis-mounted luggage bags, and a fairing.

So, it’s War again – but not as we ever knew it before, because this time around the fact that each company’s weapons are directly derived from its streetbike range, means the old Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday mantra has been reborn, but in a most improbable context. The Bagger race series has now become the direct two-wheeled equivalent of NASCAR.

For after a debut KOTB exhibition race at Laguna Seca in 2020 was won by Tyler O’Hara aboard Indian’s then-new Challenger model, MotoAmerica staged a three-race series as part of its American Superbike race programme in 2021. This was dominated by Harley-Davidson’s official Screamin’ Eagle Race Team’s Kyle Wyman, who wrapped up the championship with two wins and a second-place finish on the factory-run Road Glide Special, with Indian’s O’Hara finishing second and Hayden Gillim taking third on the Vance & Hines Harley-Davidson Street Glide entry. So, with its FTR750 already dominating AFT/American Flat Track racing ever since its 2016 inception, Indian then decided to ramp up its Bagger racing involvement, enlisting its partner S&S Cycle to develop a much more highly tuned version of the Challenger racer for O’Hara and his British then team-mate, veteran former MotoGP racer Jeremy McWilliams, to take it to Harley in 2022.

It was a decision which paid off for the Minnesota-based manufacturer, with Tyler O’Hara clinching the 2022 KoB title in a nailbiting rain-lashed finale in New Jersey by splashing to a second-place finish behind Harley-Davidson’s Travis Wyman. His season-long consistency – he was fourth or better in each of the seven races – allowed O’Hara to secure the Championship by 10 points from Wyman, two ahead of brother Kyle, with Indian teammate Jeremy McWilliams fourth in the final standings.

It was a decision which paid off for the Minnesota-based manufacturer, with Tyler O’Hara clinching the 2022 KoB title in a nailbiting rain-lashed finale.

This meant a miffed Harley-Davidson considerably ramped up its 2023 race budget in an effort to regain the KoB title from relative minnow Indian – whose annual production is one-sixth that of Harley – which intensified development of its Challenger RR via its race partner S&S. But the two factory teams took lumps out of each other, with clear evidence of over-tuning and consequent engine blowups, leaving privateer Hayden Gillim to clinch the title on his Vance & Hines Harley Road Glide by dint of scoring points in every race, with three victories and zero DNFs in the 14-race series, with teammate James Rispoli as runner-up, again with a 100 per cent finishing record.

Privateer Hayden Gillim clinched the 2023 title on his Vance & Hines Harley Road Glide by dint of scoring points in every race, with three victories and zero DNFs…

The S&S employees comprising the Mission Foods-sponsored Indian factory road racing team have until now all squeezed in their duties at and travel to the seven double-header race meetings alongside their regular roles at the Wisconsin-based tuning company, and none more so that S&S’s Director of Engineering Jeff Bailey, a 26-year company veteran, and former Bonneville record holder on V-twin bikes he tuned himself. Apart from overseeing R&D on the Challenger racer, Bailey – who’s best known for designing the S&S X-Wedge motor back in 2004 that’s powered countless customer V-twin motorcycles from America’s boutique bike-builders – also co-drove the Team’s tractor/trailer transporter rig to each racetrack.

Director of Engineering Jeff Bailey, a 26-year company veteran, and former Bonneville record holder on V-twin bikes he tuned himself.

That included Indian’s pre-season test at Southern California’s 2.68mi/4.31km Chuckwalla Raceway on the edge of the Mojave Desert, where on a bitterly cold but sunny February day I was invited to be the only non-Yank in a small group of journos invited to sample the challenge of riding the bike that Jeremy McWilliams had raced to victory on the Daytona bankings one year earlier, with advice from the most versatile road racer ever on how to do so. Since then, Jeremy has decided that with his 60th birthday coming up this year maybe it was time to step back from full-on factory road racing, leaving a vacant seat that Indian was intelligent enough to recruit Troy Herfoss to fill.

The MotoAmerica KOTB series is for race-prepared American V-Twins equipped with a fairing and chassis-mounted twin luggage bags, which must evolve from streetlegal motorcycles carrying a VIN code on the frame. This must be unmodified, although Indian secured an exemption to shorten the Challenger’s front frame spars wrapping the stock radiator by an inch or so, to stop them grounding at the incredible 60° lean angles Herfoss and O’Hara crank their SuperBaggers over to (against a stock 31°!) in maxing out turn speed.

To stop them grounding at the incredible 60° lean angles Herfoss and O’Hara crank their SuperBaggers over to (against a stock 31°!) in maxing out turn speed…

The original-shape bodywork must be retained albeit in whatever material is preferred, so while the Challenger racer’s front fairing is a stock injection moulded item straight off the production line, its rear-mounted bags are made in carbon fibre to help push weight distribution forward. There’s a 620lb/281kg minimum weight limit including oil, water and any remaining fuel in the cut’n’shut stock gas tank after each qualifying session or race.

This requires the cast aluminium-framed Challenger to carry 15lb/6.80kg of ballast, which Jeff Bailey says brings it to the 624lb/283kg mark the team usually runs to counter inconsistencies in each racetrack’s scales! That’s quite surprisingly split 51/49% static, without rider – look at the bike side-on, and it looks w-a-a-y long, which it is, and rear-biased weight-wise, which it’s not.

“. This requires the cast aluminium-framed Challenger to carry 15lb/6.80kg of ballast, which Jeff Bailey says brings it to the 624lb/283kg”.

For long it certainly is, as despite the stock cast aluminium swingarm being retained (albeit heavily braced), Bailey says the Indian must be run as short as possible owing to the conversion to chain final drive from the stock Challenger’s Gates belt, complete with a jockey wheel added to maintain required tension. “The Öhlins TTX36 rear suspension works better with the shorter swingarm, even if for overall vehicle dynamics longer is better, so as to get more weight onto the front wheel,” he says. “But we’re now running the bikes as short as possible, because we can work out the chain run and gearing better.”

This delivers the 1640mm wheelbase as ridden at Chuckwalla that’s still mega-rangy by road racing standards, with the fully adjustable 48mm Öhlins FGR250 Superbike fork set at an unmodified 25° rake, with 114mm trail delivered via an adjustable S&S-made billet aluminium tripleclamp, with just 15mm of offset. “Together with the stock rake that we’ve retained this gives us extra front ride height in pursuit of the greater necessary ground clearance, in giving 170mm of wheel travel,” says Bailey. “This is the biggest challenge in making these bikes into racers, plus the larger diameter fork tubes give greater rigidity under braking.”

After much experimentation the stock Challenger’s original 19in front/16in rear wheels were eventually replaced by 17-inch British-made Dymag UP7X forged aluminium items, a 3.50in front and 6.00in rear shod with Dunlop control tyres. These wheels carry German-made 320mm Alpha Racing front brake discs gripped by Brembo Stylema radial monoblock calipers via a Galespeed 19×19 master cylinder, with a 10.5in/268mm US-made EBC steel wave rear disc with four-piston Hayes caliper and a Beringer master cylinder, operated on O’Hara’s machine via a thumb lever, but on the McWilliams racer with a conventional lever.

Challenger’s original 19in front/16in rear wheels were eventually replaced by 17-inch British-made Dymag UP7X forged aluminium items.

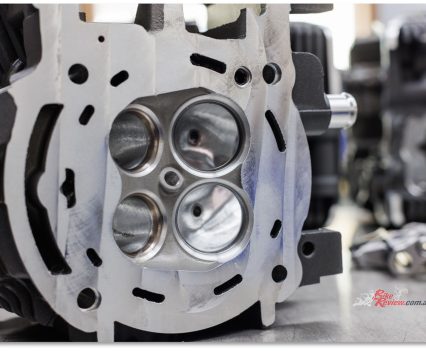

The Challenger’s stock 108 mm x 96.5 mm 1768cc/108ci eight-valve PowerPlus street motor making 121bhp@5,500 rpm at the crank and 178Nm/131lb-ft@3,800rpm, has been bored out 2mm to 1834cc/112ci by S&S via forged CP/Carrillo pistons mounted on stock conrods, which now deliver a 13:1 compression ratio thanks also to tricked-out CNC-ported cylinder heads.

With the 39lb/17.70kg stock crankshaft lightened by a maximum of 10% of the original weight per KOTB rules, but with the main bearings locked in place for increased durability, this helps deliver a significant increase in power and torque for the liquid-cooled 60° V-twin motor with chain-driven SOHC, with ‘more than 190 bhp@7,700rpm’ which is already pretty respectable – but with humongous peak torque of ‘over 150ft/lb [203 Nm]@5,000rpm, which is something else entirely. Phew!

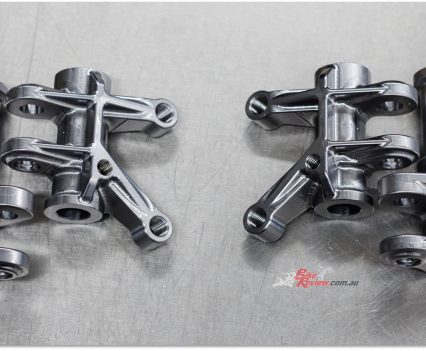

This comes with the aid of S&S racing camshafts offering both greater lift and extra duration to the stock 43mm inlet/36mm exhaust valves – two of each per cylinder, remember – operated via all-new rocker arms each different one than another, and machined at S&S out of solid steel billet. “We’ve really focused a lot on airflow,” says Bailey, “hence the custom side-mounted induction system with just a single-bore 78mm throttle body made by BBK Performance in Deland, Florida for a Chevrolet V6 car.

“We’ve really focused a lot on airflow,” says Bailey, “hence the custom side-mounted induction system with just a single-bore 78mm throttle body”.

The problem is that the stock airbox is actually the frame backbone, so this restricted airflow in search of power. This led us to install this throttle body to replace the twin stock oval-section 52mm ones. It’s not ideal since there’s a big curve in it that points the throttle body out the side, but while having that bend isn’t great, it’s better than trying to breathe through the stock frame. Not using the frame as an airbox means we can stick ballast there – lead bricks fit in perfectly right where the air filter used to be!”

This radical approach to intake design paid off big time. “We found about 30 bhp more for 2022 over ’21, with the single-bore throttle body part of that horsepower,” says Jeff. “So when we went to Daytona that year, we kind of gave Harley a sucker punch, which let us win both races on a power track.” A key element in this was the constantly evolving S&S 2-1 stainless steel exhaust with massive two-inch/51mm headers expanding to 2.5in/63.5mm in diameter. In creating this and other trick parts for the KoB Indian, S&S has employed many high-tech manufacturing aids, as Jeff Bailey is eager to underscore. “We’ve got a laser sheet metal cutting tool we use to make many custom parts like the fairing stays or the belly pan, and several parts like the aluminium intake manifold and the plastic outer runner are 3D printed.”

“A key element in this was the constantly evolving S&S 2-1 stainless steel exhaust with massive two-inch/51mm headers expanding to 2.5in/63.5mm in diameter”.

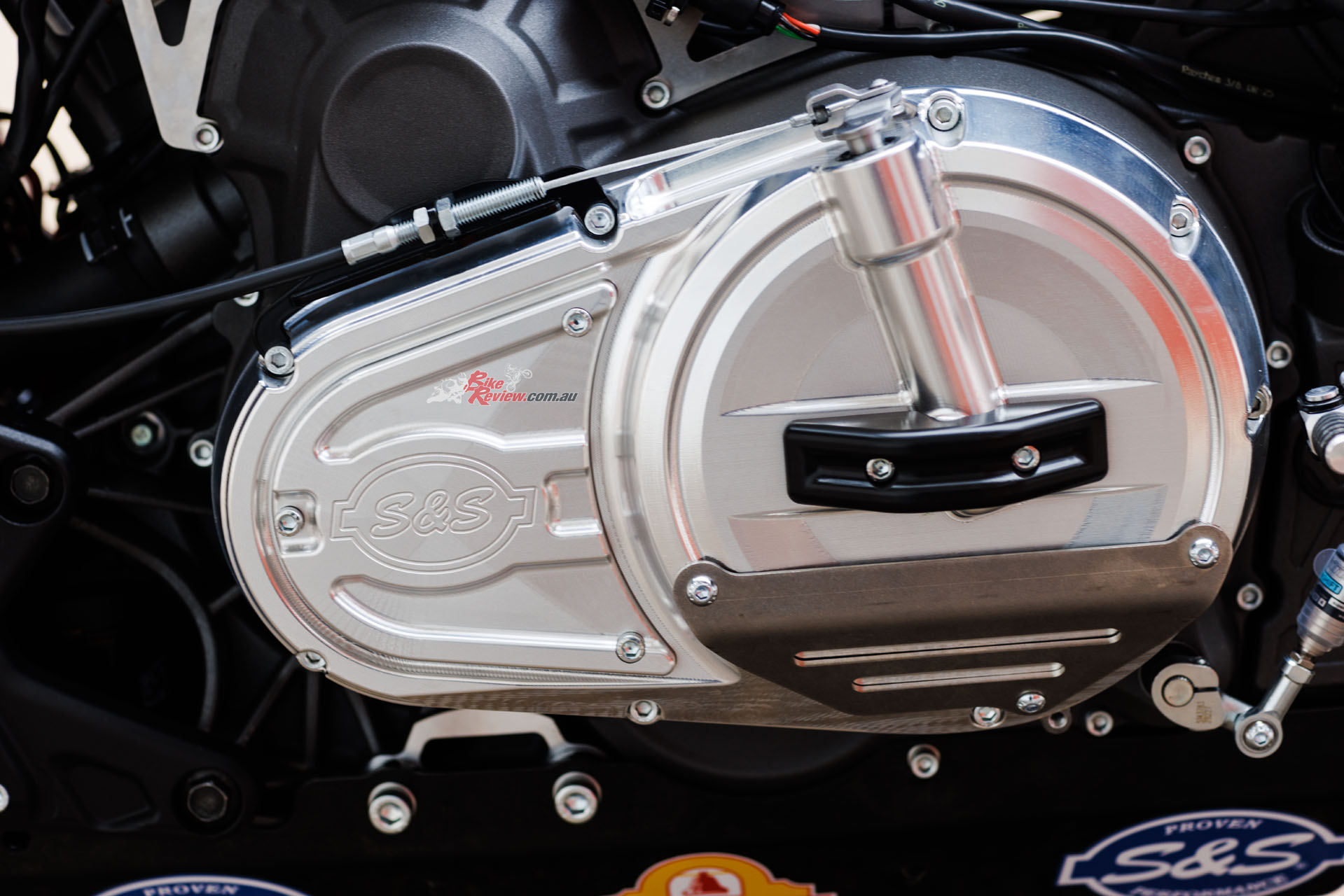

With no rider aids allowed under KOTB rules despite the ride-by-wire digital throttle – so, no TC/traction control on a racer with over 200Nm of torque! – S&S installed a Swedish-made MaxxECU Sport control module with custom wiring harness incorporating a two-way powershifter for upshifts, and an AIM DL2 dash and data logger. “Despite them being a more automotive focused company we chose the Maxx as a relatively low cost, easy to use package to control a throttle by wire system,” says Bailey. The stock six-speed gearbox has been retained, but is now matched to what is a must-have custom-made Adler slipper clutch – imagine chattering the rear wheel into a turn by using too many revs on a downshift on such a motorcycle!

The prototype Adler package worked so well it was adopted on the 2023 Challenger/Pursuit production streetbikes

The prototype Adler package worked so well it was adopted on the 2023 Challenger/Pursuit production streetbikes – see, racing really does improve the breed! The S&S custom clutch cover was created to aid ground clearance, with the operating lever flipped up to the top side to avoid grounding. Similar concerns made S&S tuck the exhaust in as tight as can be to the motor – it’s about halfway up the bike on the right, but incredibly is still a ground clearance issue for the factory riders. “They were dragging the mufflers so hard it was breaking the brackets, and wearing the badges off them!” says Bailey.

THE RIDE

I had no worries this would be an issue for me in my five allotted laps on Jeremy McWilliams’ Daytona-winning bike, especially as it was my first time riding Chuckwalla’s flowing but featureless expanses, and the cold temperatures meant we had to run Dunlop Sportmax Q4 street rubber, rather than the usual slicks. Climbing aboard the SuperBagger’s custom Saddlemen race seat took quite a bit of doing – though this is set quite low, the Indian is pretty wide, thanks to the fuel tank shroud now encompassing the side-mounted throttle body on the right.

So I had to lever myself aboard via the incredibly high left footrest, and once installed there I found a really contradictory stance for such a huge-seeming motorcycle. You’re well aware at all times of just what a vast piece of two-wheeled real estate you’ve climbed aboard, yet paradoxically the actual riding position is quite cramped, despite the fact that it seemed I had to reach halfway to Mexico across the fuel tank to grasp the flat-set clip-ons bolted to either end of the thick bar clamped to the laser-cut upper triple-clamp, while at the same time struggling to lever my feet up high enough to park them on those ultra high-set footrests.

“It seemed I had to reach halfway to Mexico across the fuel tank to grasp the flat-set clip-ons bolted to either end of the thick bar”.

Reassuring, it’s not, even if the footrests must be that high to avoid grounding out when Troy and Tyler crank their Baggers over to the 60° lean angle they aim to obtain in keeping up turn speed, and at rest I could barely touch the ground with the toes of either boot. Once ensconced in the pretty wide, deep-mounted seat behind the thick rubber pad attached to the back of the tank, I realised the Bagger’s screen was ultra-minimalist – it merely acted as a wind deflector over the top of the AIM dash.

Unlike Harley, Indian had not yet put its champion Challenger in a wind tunnel, and I think it showed. Besides acting as a data-logger, this dash shows the gear selected on the left above the engine map chosen, with a digital tacho on the right plus the water temp. Thassit. There are several small switches on the left ‘bar, one offering a secondary choice of engine map, another two levels of aggressiveness with the throttle map, another for the pit lane speed limiter, then launch control, and the fuel pump.

Thumb the starter button on the right ‘bar, and the Indian thunders into life like one of the denizens of the Battle of the Twins class resurfacing from 40-odd years of slumber. I mean, this bike sounds purposeful! Notching bottom gear with a clunk on the one-down street-pattern gearchange, I tried slipping the clutch lever ready to depart – but then suddenly the Indian leapt forward, and fortunately took me with it! “The launch control is very, very helpful, and they should have let you use it,” said a watching Jeremy afterwards. “It’ll only let it rev to 3,000rpm, and then we let the clutch out, and it works everything else out for itself. We’ve seen 0-100km/h times of 2.4 seconds, MotoGP territory!

“We’ve seen 0-100km/h times of 2.4 seconds, which is MotoGP territory!”

So with a long bike, a lot of grip, big hot sticky tyres, and a couple of clever EFI guys, we can launch the bike up the road quicker than a factory Superbike. Our starts have always been pretty good, and it’s so important in this class that you don’t get caught up in the midfield.” Finding a way round the on/off clutch action would be important, but it reminded me up front that this 1815cc/111ci maxi-motor spins up super-fast thanks to the lightened crank, and reduced internal friction.

Noting that at no stage had the long wheelbase Indian wheelied despite the humungous amount of torque I must have inadvertently tapped into, and secretly satisfied I’d caught the motor and hadn’t stalled it, I shifted straightaway into second, and then almost at once into third via the crisp, wide-open powershifter – the bottom four ratios in the Challenger gearbox are very close together, with a much bigger gap to fifth and top, as required by the Cruiser customer this engine was created to serve.

“We’re limited on how much we can rev such a high-capacity motor,” said Jeremy, “so the gear ratio spread creates its own little issues when you’re trying to find the perfect gearing for a track. After getting off the line we’re frequently using third, fourth and fifth gears only in races, especially on faster tracks like Daytona and Road America.”

“Face it, this bike wasn’t designed to be raced, so the loose handling is all part of life’s rich passion when racing a Bagger”…

I spent the first two laps out of my precious five aboard the RaceBagger trying to come to terms with the curious riding position and with that massive torque which I could feel peaked out at around 5,500rpm, but then kept on giving up right to the unexpectedly hard-action 7,700rpm rev-limiter. Despite its RbW digital throttle, the Maxx ECU enforces a sharp cutout which on such a low-revving engine with such heavy rotational inertia meant each time this happened I lost momentum while it recovered itself.

This initially made me think I needed to ride the torque curve – logical, you’d think, with so much on offer – but then as I speeded up I found the Challenger was increasingly washing out the front wheel round Chuckwalla’s several long, constant-radius turns if I tried to take these at around 5-5,500rpm, necessitating a good heave to combat the understeer and bring it back on line, which was bloody hard work on such a long, heavy bike.

So on lap 3 of my five I switched strategies, instead holding a gear lower and letting the PowerPlus engine rev right out. Bingo! The long wheelbase monsterbike wasn’t exactly transformed into a two-wheeled Prince Charming, but it held a tighter line, and let me stay hard on the throttle for longer. There were two shifter lights – a yellow one at 6,900 rpm and a final warning red one 500 revs later, and provided I clicked the powershifter immediately this light fluttered, I’d find myself back in the fat part of the power curve without hitting the limiter, still holding my chosen line.

Read Alan’s test on the Indian Super Hooligan FTR Racer here...

The only downside was that the harder I revved the motor the more it vibrated – not offensively so on a short 10-15-minute ride, but still noticeably enough. KOTB teams aren’t allowed to alter the stock balance shaft, and on the Indian this was obviously no longer weighted correctly after S&S removed so much metal from the crankshaft, and fitted the big-bore pistons.

Though I can’t say that in my five-lap taster of a test on a new track I could start to exploit the Indian Bagger’s handling capabilities, several features of that were evident after my brief ride. Firstly, even with the street tyres the chassis likes to wriggle around under the application of all that power and especially torque, making me glad there was an easy-access steering damper in front of my left knee.

“I wouldn’t exactly call it agile, but it was surprisingly adept at taking Chuckwalla’s blind left/right hilltop chicane in second gear on a trailing throttle”…

Face it, this bike wasn’t designed to be raced, so the loose handling is all part of life’s rich passion when racing a Bagger – and is undoubtedly one reason it’s become a crowd favourite. These bikes look every bit the handful to ride that they actually are! Second, although the sense of detachment from the seemingly distant front wheel meant it was hard to feel committed to steering the Indian in turns, it did change direction well, far better than anything this long has a right to do.

I wouldn’t exactly call it agile, but it was surprisingly adept at taking Chuckwalla’s blind left/right hilltop chicane in second gear on a trailing throttle, ready to crack it open descending the hill to get a strong drive out of the right-hander at the bottom, with the engine pulling hard at just under seven grand. Taking it a gear higher and surfing the torque curve at lower revs had meant it washed out the front end, and stopped me getting on the power again so quickly.

“Having to adapt your style to riding this motorcycle is quite different to anything else, and it has to be ridden out of your comfort zone.” Jeremy McWilliams…

The Indian SuperBagger also – again, improbably, given how heavy it is – braked well from high speed. The big German-made 320mm Alpha Racing front discs and their Brembo Stylema 4P radial calipers stopped this monolithic motorcycle unexpectedly well – but only if I a) hit the 10.5 in/268 mm EBC rear disc with its four-piston Hayes caliper really hard as well, b) used the considerable amount of engine braking on offer despite the slipper clutch, and c) did not try to trailbrake into the apex of a turn, which the Challenger absolutely does not like doing, weaving around the place as you try to position it to hit the apex of a turn.

‘“I believe the reason why that’s happening is because it makes more grip than anything else due to the load that it puts to the tyres as we’re relying so heavily on backshift and brake,” said Jeremy. “So because we’ve got so much load going through the rear tyre, the bike then tends to get itself crossed up, and starts moving around coming into a bend. Having to adapt your style to riding this motorcycle is quite different to anything else, and it has to be ridden out of your comfort zone. So you’ve got to do all your braking in a straight line as upright as possible – not like when I so nearly crashed in Turn One coming off the banking at Daytona in the race I eventually won, which taught me that it doesn’t like to be braked hard when leaned over. Sounds like you’ve found that out, too!”’

Yes, indeed – and even in a measly five-lap introduction I found this literally amazing motorcycle kept asking me new questions, some of which I answered before being posed with the next one. I hope I get the chance to get to know it better – but meantime one thing’s for sure: anyone who races one of these bikes – Harley or Indian – is an absolute hero, and the level of skill and bravery it takes to get to Victory Lane in doing so cannot be overstated. For Troy Herfoss to do what he’s done so far on this bike is literally incredible – and will certainly have got the Harley team worried. His numerous Aussie fans – and quite a few newly-minted American ones, too – will hope he’s able to go one better in front of the MotoGP elite and the packed grandstands at Austin this weekend!

INDIAN CHALLENGER KING of the BAGGERS Specifications

Engine

Liquid-cooled 60º four-stroke liquid-cooled SOHC, four-valve per cylinder (43mmIN/36mmEX) V-Twin, gear driven counterbalaner, 110 x 96.5mm bore x stroke, 13:1 compression, 1834cc (112ci), EFI/EMS with MaxxECU Sport ECM, single injector per cylinder, 1 x 78mm BBK/Dodge Charger throttle-body, six-speed gearbox with gear primary drive, wet multiplate Adler oil-bath slipper clutch.

Chassis

Cast alloy backbone frame, fully adjustable 43mm Ohlins FGR250 inverted forks, cast and braced alloy swingarm with fully adjustable Ohlins TTX36 shock, 1640mm wheelbase, 25º rake 15mm offset, 114mm trail, dual 320mm Alpha Racing steel rotors (330mm Brembo on O’Hara bike), four-piston Brembo Stylema M4 calipers, GaleSpeed 19mm master-cylinder, single 268mm EBC steel rear disc with four-piston Hayes caliper, Beringer master-cylinder, Dymag UP7X forged alloy wheels (3.50 x 17in, 5.50 x 17in), Dunlop 130/70 – 17 and 200/55 – 17 Sportmax Q4 tyres.

Performance

Top Speed: 176mph/283km/h (McWilliams, Daytona 2023), Weight: 283kg oil/water and remaining fuel after race/qualifying plus 6.80kg ballast split 51/49% without rider. Power: 190hp@7700rpm, 203Nm@5000rpm.