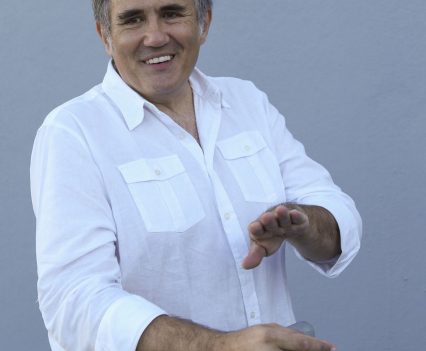

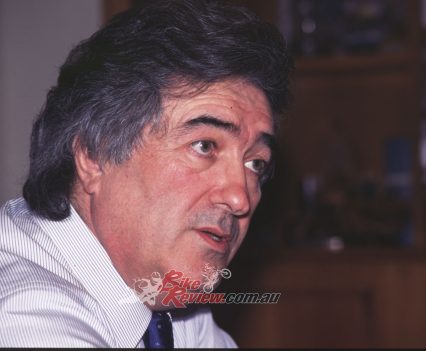

Miguel Angel Galluzzi, the name responsible for pulling Ducati out of some serious financial trouble. He tells us the story of how he come up with the famous Ducati Monster design!

There’s a valid case for stating that the Ducati Monster is the single most important motorcycle to be produced anywhere in the world since the original Honda Super Cub debuted back in 1958. This is the history of the most distinctive nakedbikes in the world!

There’s a valid case for stating that the Ducati Monster is the single most important motorcycle to be produced anywhere in the world since the original Honda Super Cub debuted back in 1958.

OK, Ducati has ‘only’ manufactured 365,000 Monsters in the 30 years from its 1992 debut up to 2022, compared to the over 100 million Cubs built so far. But this motorcycle is not only the best-selling Ducati model ever, it’s also the one which saved the Italian manufacturer from going bust in the 1990s, and represented a crucial lifeline for the Bologna factory in allowing it to survive long enough to be purchased in 1996 by American investors TPG, and set on the path to its present success as part of the VW Audi Group.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

In 1999, the M600 midi-Monster variant was the best-selling motorcycle model of any kind in the Italian home market – the first time any Ducati had ever achieved such status. And in 2001 the debut of the S4 Ducati Monster powered by the 916 Superbike’s desmoquattro 8-valve engine opened the door to a new, more performance-conscious Naked bike market.

This motorcycle is not only the best-selling Ducati model ever, it’s also the one which saved the Italian manufacturer from going bust in the 1990s.

Building on the model’s cult status as a two-wheeled icon, the 43 different Ducati Monster derivatives built to date have in some years represented over 70 per cent of Ducati’s total production – but, it’s been the most-copied motorcycle ever produced by an Italian manufacturer, rivalling BMW’s GS family in establishing a new style of bike whose commercial success invited instant imitation.

How many bikes look like the Ducati Monster now? A dramatic leap of faith by the manufacturer turned the nakedbike world on its head with a design that is still copied to this day.

The man responsible for single-handedly creating the Ducati Monster – and for naming it! – is Argentinian Miguel Angel Galluzzi, now 63, and today the Director for Advanced Design of the Piaggio Group, based in Pasadena, California. Let’s leave it to him to tell the story firsthand of how he created the Ducati Monster that made its public debut at the Cologne Intermot Show in Germany exactly 30 years ago in October 1992.

“I saw the movie On Any Sunday in Argentina when I was 12 years old. I went to see it so many times that the guy at the cinema selling tickets would let me in free! The sight of Malcolm Smith and Steve McQueen riding in the desert was paradise, but it was something we could only dream of doing. When I was 15 I began racing Motocross with Zanellas – crude locally-made bikes, because back then in Argentina importing foreign bikes was forbidden. They’d smuggle Husqvarnas and Suzukis in from Uruguay or Paraguay, and I remember seeing a Honda Elsinore someone had brought in from Chile – it made me think of that movie!”

Galluzzi told the story firsthand to Cathcart of how he created the Ducati Monster that made its public debut at the Cologne Intermot Show in Germany exactly 30 years ago in October 1992.

“In 1978 I had to do my Military service, fortunately before the Falklands War! I’m a big guy, so I was the bodyguard for an Admiral in the Argentinian Navy, which meant a lot of sitting around and waiting. To pass the time I’d always be drawing motorcycles and cars. I love drawing – I got bad grades at school because of this, because I’d be at the back of the class drawing bikes since I wasn’t interested in the lessons!”

“I love drawing – I got bad grades at school because of this, because I’d be at the back of the class drawing bikes since I wasn’t interested in the lessons!” – Miguel Angel Galluzzi

“I finished my Military service, and I was 19 years old, so now what? I discovered the Art Center College in Pasadena, California where you could study Industrial Design. I remember getting my cousin to write the application letter, because my English then wasn’t very good! So I went to Pasadena, and did a couple of motorcycle projects there, plus a scooter. After graduating I tried to get a job with Yamaha or Honda who both had design studios in California – but they couldn’t hire me, since I wasn’t American. So my first job was in Europe with General Motors at Rüsselsheim in Germany, and that’s how I ended up in bikes.”

“I was in the Opel Corsa design studio, where my boss was Hideo Kodama – a very sharp Japanese guy who was an excellent designer, as well as a very perceptive person. I was doing a lot of sketches for him, but he said, “I like what you’re doing, but I can see you don’t enjoy this”. I told Hideo-san, “I’m not going to stay here for more than two years, because I really want to work on motorcycles – so do you have any friends in that sector who are looking for someone?” Well, he knew some people in Honda Germany, so I got in touch with them. At that time, Mr. Honda was still alive and they had a project to open a studio in Milan, because that was his dream – to have a design studio in Italy to focus on future mass mobility. So they offered me a job there, and I went to Milan to work in a studio near the Duomo, with two Japanese guys, an Italian designer, and a secretary.”

“I met some great people there, like Hitoshi Ikeda, the designer of the CB750 K0. But the first thing I did when I came to Milan to work for Honda was to buy a Ducati! I found a dealer with this silver and red 750SS for 7,500,000 Lire, which was quite a lot of money – but I said, if I don’t do it now, I never will. So I bought it and began riding it to work, because I was living about 15-20km outside Milan, and to commute by motorcycle was much faster.”

Deep down, every motorcyclist is a Ducati fan. Even the head designer for Honda had his heart set on a Ducati…

“I remember going to Honda for the first time with my Ducati, and the parking garage was underground. Mr. Ikeda was in the office that day, and he came to my desk and asked me, “Did you buy a motorcycle yet?” I said, yes, I bought a Ducati 750. “So why not a Honda?“ Because I like Ducati’s. “Where is the key? Come with me!” I thought – oh man, I’m in trouble. So we went to the parking lot and found the bike, he put the key in and started the engine – and suddenly his face changed. He went vroom, vroom, with the throttle – and then he turned to me and said, “You know what, this bike has a heart – we Japanese are never going to be able to make something like this.” And from then on every time he’d visit the office he’d take the key to start the Ducati, blip the throttle, and then come back with a huge smile! He understood bikes very well.”

“In Honda Milan we were working on scooters and other transportation projects. I remember very well the first project I was given. Since I speak Spanish they sent me to Barcelona to just walk around and look, and talk to people. So I started walking the streets of Barcelona in 1987 which was not what we know today – it was a different city back then, very old fashioned, quite run down, but in the process of an industrial and social revolution in recovering from the Franco era. There were a lot of noisy Derbi and Montesa two-strokes, but anyone who could afford a motorcycle had one – this was their basic transportation for getting around. So I did a lot of sketching there – I walked about together and I spoke to people, and then came back to Milan and did a project called ‘Future Mobility for Honda’ with a young Italian colleague. We did all the sketching for this in Milan, and our boss took them to Japan. So when he came back, we asked him how it went. “Terrible. They didn’t like anything. We are really bad.” So we were very depressed.”

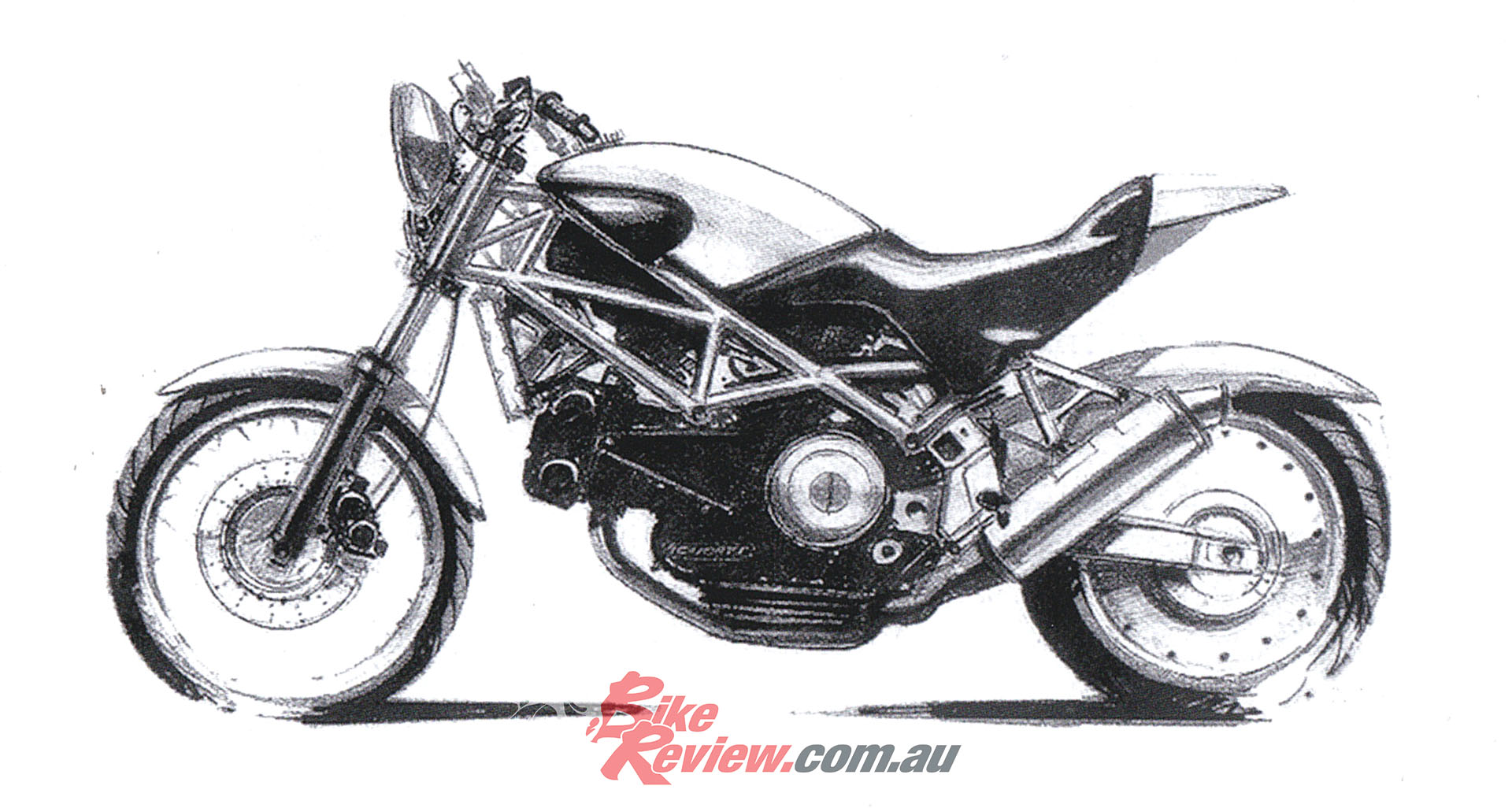

The final sketch of the Ducati Monster before Galluzi started chipping away at a full-sized concept…

“Then in November 1987 came the Tokyo Motor Show, and the following month in Milan we got a Japanese magazine reporting on that. There on the cover we saw these different Honda interpretations of two-wheeled personal transportation – small-wheel, big-wheel, scooters, mopeds – and of these eight or nine proposals, there were three that were ours! So the other Italian guy and I went to our drawers to see the sketches – and the sketches were gone. I went to my boss and asked what happened, and he said no, these were all done in Japan. I said no, no, no – we did those sketches right here. He said – no, they did them in Japan. Then I realised they were very jealous because we and other studios abroad were always feeding Japan with stuff, but to outsiders it must be seen to have come from Japan. I was really mad, so I decided to leave Honda – how could I ever progress if my designs were being stolen, and claimed to be done by someone else?”

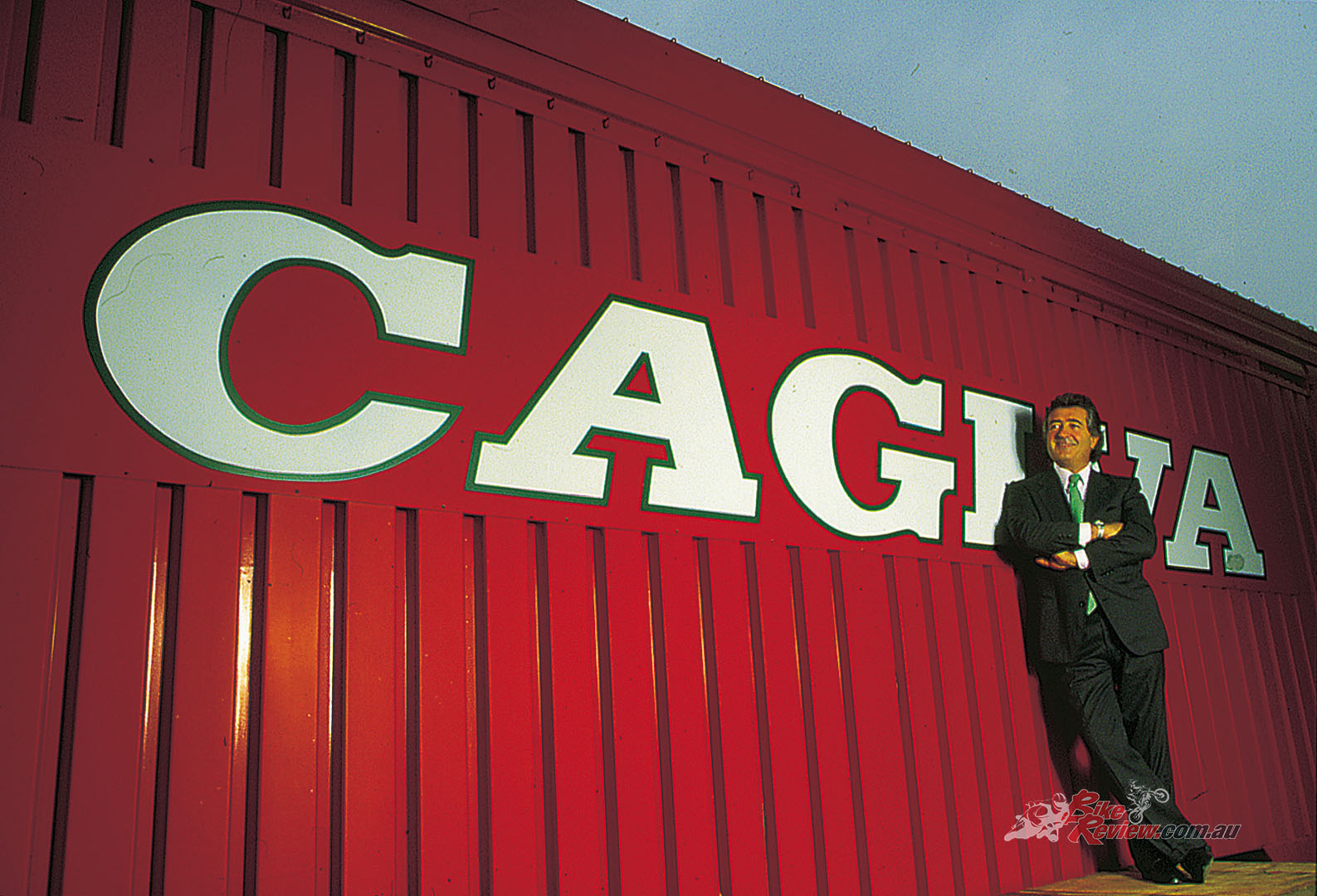

“I’d met a guy who used to work in Cagiva, Daniele Vitali – so he arranged for me to be invited there for an interview. I remember leaving Milan in thick fog, then halfway to Varese the sun broke through, and the sky was bright and clear. I drove into the parking lot at Cagiva beside the lake, with Monte Rosa in the background, and I remember going into Claudio Castiglioni’s office, and before even sitting down I told him – it’s so beautiful I’m ready to come and work here right now! He laughed a lot – and the interview we had was fun, because we started talking motorcycles, about this bike and that bike – we were talking for an hour and a half, and then he said “OK, I’m going to give you a job, but first come with me.” So I went with him to meet his brother Gianfranco in the office above, who had somebody sitting there with him drinking a bottle of red wine. Claudio tried to explain who I was, and he said ‘Here, have some wine and tell me what you think we should do at Cagiva’. I thought, these people are crazy – but I like them! We can do something good here!”

Claudio out the front of the Cagiva factory. The late 80s/early 90s were a peak time for the Italian brand, running on the hopes and dreams of two brothers.

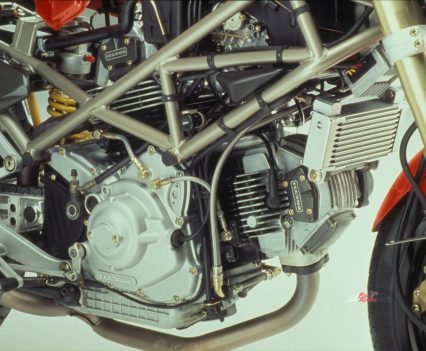

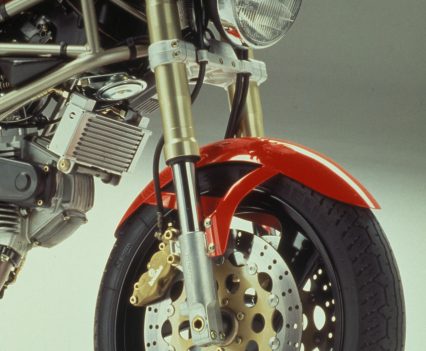

“While I was working at Honda, we used to receive the Japanese magazines, and Riders Club printed large photos of important motorcycles without the bodywork. One day this arrived with the first 851 Ducati stripped naked inside. They’d simply removed the bodywork in order to take the side-on shots. I made an A3 colour photocopy of this 851 photo and said to myself, this is the bike I want to make – it’s what I’d like to ride myself. Forget about all the race bodywork and stuff that is completely pointless riding on the street – they’re just gimmicks to try and sell it. I want to build this bike just as it is, without all that plastic.”

A Ducati 851 with no fairing was the main inspiration for the Ducati Monster. Here is one of Cathcart’s machines, do you see the similarity yet? Photo: Silodrome.

“So I went to work for Cagiva, and I remember meeting the boss of Ducati, Massimo Bordi. He was a bit scary, but at the first meeting we had, I tried to convince him we needed to do this Naked bike. I drew him sketches of it and he said, OK, OK – one day we must do this, but here’s something else you must do first. Then he became the Technical Director for the whole Cagiva Group, so he was my boss, and each time he came to Varese from Bologna, I tried to remind him about the Naked bike idea I had. But it was, “OK, Galluzzi – nice idea, but don’t bother me now with that, please’.

“But I was young and really tenacious about it, so in 1990 it was summer, and back then in Italy we stopped work for the whole month of August. So I asked Bordi if since I was going on vacation, can I get some parts, so I can draw some sketches? He said yes – I think he really wanted to get rid of me, so he said to go to Ducati and get whatever I wanted – it was like, let’s allow this kid do something so he doesn’t bother us anymore! That August, Claudio Castiglioni lent me his new 888 Strada, the first red desmoquattro with the 17-inch wheels, because I had my mother-in-law living in France, in Antibes on the Cote d’Azur, and my wife and kids went to stay with her. I would ride back and forth on the 851 to spend the weekends with them, so I was able to ride it quite a lot, and I realised it had a great engine that could really be the basis of the bike I wanted to build.”

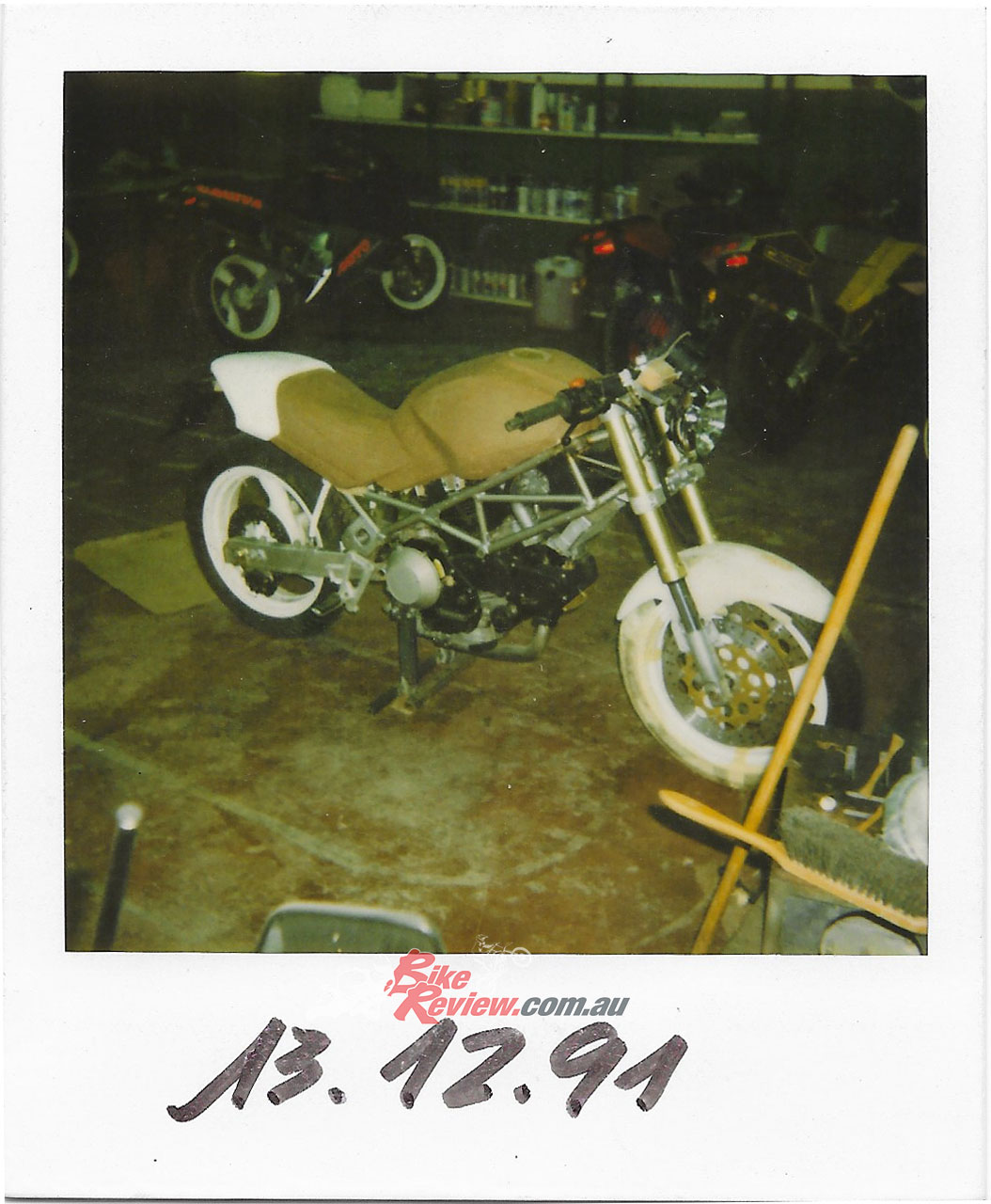

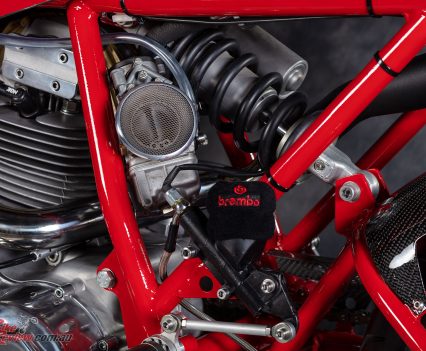

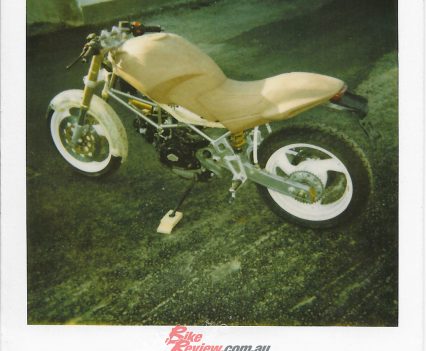

“So I got an 851 frame, thinking that I could use the liquid-cooled eight-valve engine for this Naked bike. But the 888 had just reached production, so it was back ordered, and anyway too expensive. But the 900SS wasn’t selling very well, so there were ready supplies of its air-cooled desmodue motor, and not having a water radiator was a good thing for a Naked bike. So I decided to use this motor instead, but with the 851 frame that had a rear suspension link, not cantilever like on the 900SS. I got the frame and started building the bike, but I needed some help, so I asked them to lend me Fabio Montanari to do it – he was the guy at Cagiva who used to make aluminium gas tanks by hand for the Paris-Dakar bikes. Because he’d make a lot of noise hammering metal he was given a small shed in the factory grounds beside Lake Varese, away from the design studio in Morrazzone, the other side of Varese. Without anybody knowing we brought the bike there to build it, so it was like a secret, because I was supposed to be at Morrazzone, out of the picture.”

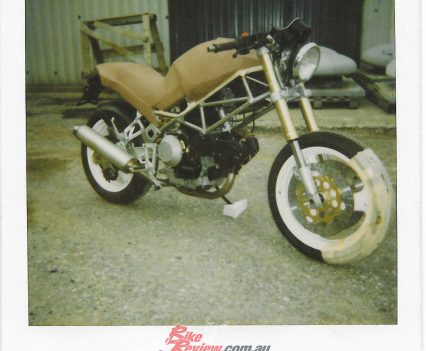

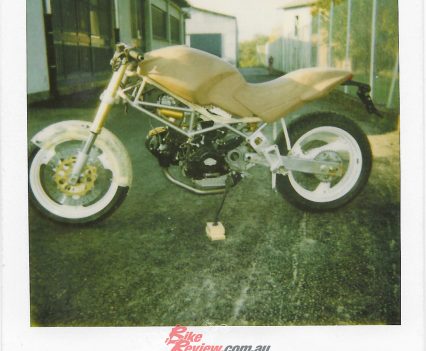

“However, one day a big discussion started in Claudio Castiglioni’s office about the investment needed to do the new Paso, and Claudio apparently asked, what’s Galluzzi doing down by the lake, and how much is it costing? So suddenly they opened the door of this little shed, and Fabio and I were in there working on the Monster, which although it wasn’t properly finished, was pretty much complete. We pulled the bike out into the open – and I wish I’d had a camera there, because I still remember the look on people’s faces! Later on, Claudio always liked to recall that moment, and I remember him touching the seat and saying, ‘Is this it – are we missing something here? Or is this finished, just like it is?’ I said, ‘No, no – that’s it.’ ‘But is there any other piece still to fit?’ ‘No – just like that is how it’s meant to be.’ So he said, OK – and then they started having a discussion about it there and then, just standing looking at it in front of us.

“I remember him (Claudio) touching the seat and saying, ‘Is this it – are we missing something here? Or is this finished, just like it is?’” – Miguel Angel Galluzzi

But the outcome was that, with Bordi pushing hard for it, they decided to do the Paso first because it was more normale, which they thought would sell better, even if it meant spending big money, for example to produce the headlight and tail light. Meanwhile, we finished the Naked prototype, and put it to one side in Morrazzone. Time went by and it got dusty, then four months later towards the end of 1991 somebody told me they were having this big meeting of Cagiva Group importers at the factory.”

“I convinced Claudio to bring the bike into the meeting, and the Cagiva importer for France, Marcel Seurat, was there, plus Germany was there, England, it was all the big importers for the whole Cagiva Group. The meeting lasted for three days, and on the last day Claudio said, ‘We have something to show you, and we’d like to ask your opinion about it.’ There was a big room at the far end of the Technical Office, and we took them in there, removed the cover, and everybody was like – ‘Wow, what is this??! The guy who reacted quickest was Seurat – he said, ‘Claudio, we’ve got a winner here – let’s get this thing going fast. I’ll buy the first thousand bikes!’ Really!”

Towards the end of 1991, Miguel had essentially finished the final concept before wheeling it into a massive Cagiva Group importers meeting.

“So all the Ducati executives looked at each other, and said, this guy is crazy – some of them meant Seurat, and some of them meant me! That was when they invented the story of how everybody said, oh, where is the bodywork, this looks like a Monster bike – but nothing happened like that. On the contrary it was, like, what do we do with this weird thing – only Seurat understood what it was, and pushed hard for the bike. But Claudio got it completely – he had a fantastic appreciation of what his customers wanted. He’d stop by 2-3 times a week to look at what we were doing, and to sit down and discuss it with us, and throw out new ideas. That’s why I spent almost 19 years with him – we always had such great discussions. He understood design very well, and we’d bounce ideas off each other. We had big arguments sometimes – but that was all part of being so passionate about it, and that’s what drove the creative process we had in Cagiva.”

Castigloini always had way more of an appreciation for the passionate side of racing rather than the monetary. This meant he saw successes but a fair few financial blows.

“I love riding motorcycles, and I’m very lucky to make my passion my job. I like to make bikes for myself – but that’s not the same as doing them for other people. It’s a different philosophy. There are some aspects of the Monsters which make them very successful, especially the ergonomics. For the first bike we needed a lower seat, because at that time most of the Street Enduros were getting higher and higher. But Claudio insisted we needed a bike that women could also ride – he was a visionary, because back then 25 years ago nobody thought of women in designing a bike, except him. At the time it didn’t seem to make any sense – but his ability to go there where nobody else did, to look at something in a way nobody else could, was why I think the Cagiva Group was always so successful, first with Ducati, then later with MV Agusta. Because their bikes told the market what to do, which is a gift that came primarily from the boss.”

“Claudio’s ability to go there where nobody else did, to look at something in a way nobody else could, was why I think the Cagiva Group was always so successful” -Galluzzi

“So we launched the bike at the Cologne Show in October ’92, and to say it was a hit is an understatement – it totally took off with the public, so all the other importers increased their orders there, about 700-800 bikes altogether in addition to Seurat’s 1,000. He was the only one who had understood it properly. I heard many stories about why we called it the Monster, most completely untrue! The real reason is that when I started working on the bike, I was spending hours on a design that didn’t have any project number – but I was spending money and sourcing parts, and the company was paying. So one day Bordi called me, and told me the financial controller needed to assign a reference number or a name to the project, to allocate the cost of all that time and money.”

“Around that time, they had a craze in Italy called Monster in My Pocket for young kids to collect small boxes with two little rubber monsters inside – there were about 300 different ones, and a plastic pyramid that you collected them all in. So each night I got home from work, my two young sons would ask me ‘Dad, did you buy us a monster – monster, monster, monster??’ Sometimes I did, and sometimes I forgot – but each weekend we’d go to the magazine store to buy three or four boxes for them to add to their collection. So I told Bordi, ‘Listen, why don’t we call it the Monster?’ And he said, ‘OK, call it whatever you want. Monster it is.’ So, Monster it became – never the Italian which is Mostro, because that’s not what it said on the boxes, always Monster! And the story about him asking me to design a bike that looked like the Triumph in the famous picture of Marlon Brando in The Wild One is as much pure fiction as any Hollywood movie script – sorry!”

“The story about Claudio asking me to design a bike that looked like the Triumph in the famous picture of Marlon Brando in The Wild One is as much pure fiction as any Hollywood movie script – sorry!”

“Anyway, that meant everyone in the company with anything to do with it was calling it the Monster. Even when we presented it to the Cagiva Board, it was called that – but then Ducati hired a company which charged megabucks for dreaming up names to give to products, and they came up with some really stupid name which I honestly can’t remember. Stupidissimo!

“Monster” isn’t what you’d expect from Ducati. But can you imagine it being named anything else? Beats being named a bunch of letters and numbers.

“Anyway, nothing was decided, so a week before Cologne we got our presentation, and on this list, there was no name attached to the model, it was just called the M900. Thank God, during this period Mr. Seurat was there and I remember him saying, ‘You really are a group of imbeciles – you already have a great name: ‘Monster’ – leave it at that!’ But when we went to Cologne the bike was still not called the Monster, because Bordi didn’t think it was a suitable name for a Ducati model – it was just M900 in all the show material and press kits. But once we got to the show, everyone from Ducati was calling it the Monster, and when we came back – again thanks to Mr. Seurat – it became the Ducati Monster again, because he started referring to it as that in talking to the French press, so they then printed this, and that was what it became, thanks to him!”

“It’s also not true that it was originally going to be called the Cagiva Monster – it was always going to be a Ducati.” -Galluzzi

“It’s also not true that it was originally going to be called the Cagiva Monster – it was always going to be a Ducati. However, the first running prototype they made in Bologna for the test riders to use was painted green, so they called it ‘Kermit’ after the frog in The Muppets. This was a deliberate insult as they didn’t like it since it wasn’t a sportbike, and [Franco] Farnè [Ducati’s technical guru] fitted a pulled-back high-rise chopper-style handlebar to it, and a custom exhaust. I saw this monstrosity – it really was a monster! – on a visit to Bologna, and I complained to Mengoli [Bordi’s no.2 in the Technical office – AC] about them doing this. I told him that wasn’t the bike I designed, so they eventually changed it back to how it was supposed to be. But the irony is that this is the model which saved Ducati, and allowed them to keep on building their title-winning Superbikes and MotoGP racers in Borgo Panigale – so maybe they think a little better of it now!”

Ducati were in serious financial trouble before the Monster came out. Funnily enough, people in the brand were trying to sabotage the Monster!

“The spirit of the Ducati Monster was born on the Los Angeles Crest Highway in 1984, because I was going to school in Pasadena, and that was the road I used to go back and forth along to get there. Back then it was easy to crash, because the bikes were crap, and the tyres too. Repairing bodywork was difficult and expensive, especially for students – so we’d remove the beat-up pieces, and the bike would still ride just as good as before, and maybe even better because there was less weight. Plus, I had a friend who was part of the group we rode with who had an old Triumph Bonneville, and he would always keep up with us on the latest four-cylinder Japanese sportbikes, and even sometimes beat us to the Rock Store on Mulholland Drive where we’d meet up at weekends.”

“Back then I had a four-cylinder GS750ES Suzuki, and still he’d always be there first. So that started me thinking that you don’t actually need that much engine performance. Then the first Honda Interceptor came out, and the GSX-R750 – so from that moment on everything got so complicated and expensive, and I ended up working for Honda designing so much plastic – but what for? What I want to do is to enjoy my ride. Can I go fast? Maybe – but I still need to enjoy my ride, and to do that I only need one engine, two wheels, a gas tank and a handlebar, and some metal to join them together. And the Ducati Monster showed that’s really all you actually do need!”

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.

February 26, 2024

When I saw M900, it was love in first sight.

I immediately ordered one wheh I was iving in U.K.

8 years lator, I had to sell it due to family situation, but I still love the design, that I think

one of the best in bike industry.

I am industrial designer, and I envy Miguell Galluzzi for persuing his passion.

Thank you for the great story.

March 5, 2024

Great story – thanks for the feedback, hopefully you get another M900 some time!