John Nutting recalls the MIRA test bike diary from 1973, the holy grail of performance data recorded on bikes from the era. Take a blast to the past with us as we revisit the bike tests of 1973...

Europe was going through dramatic changes with their motorcycle manufacturing in 1973, Japan had well and truly proved that they could match and best the bikes of the Western world. These changes were reflected in my MIRA performance data files…

The British motorcycling scene was going through dramatic changes in 1973, and they were reflected in John’s MIRA Files from the period. Get the full run down of all the wacky stuff that was going down in the 70s.

What does MIRA stand mean for those who aren’t seasoned British motoring readers? It was where I would collect the performance data, the Motor Industry Research Association’s proving ground near Nuneaton in Warwickshire for the weekly newspaper, “Motor Cycle”.

I’d been at the paper for just eight months but it couldn’t have been a better time to sample machines that were the last gasps of the British factories alongside the new order of Japanese superbikes that were supplanting them. It was the year in which the Yom Kippur war in the Middle East led to a dramatic rise in petrol prices; when the UK joined the EEC; strikes resulted in the three-day week and power cuts; Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon was released; and my racing hero Jarno Saarinen was tragically killed along with Renzo Pasolini in a horrific accident at Monza in Italy.

MIRA Aerial View

The range of machines available for testing by magazines was much more limited than today, mostly because there were fewer models and overseas manufacturers rarely had their own wholly-owned subsidiaries with generous budgets in the UK.

Machines tested on MIRA’s timing straights included a number of new models from Triumph and Norton, sportier BMW boxer twins to augment their tourers, Italian machines from Benelli, Laverda and even an MV Agusta. From Japan new two-strokes from Yamaha and Suzuki were tested, along with Kawasaki’s amazing Z1 DOHC four. Honda was notably absent from the test-bike list for 1973: having launched the superbike era four years earlier with the CB750 the factory had been more concerned with developing its automobile range.

The BSA-Triumph group, with factories at Small Heath and Meriden, had been suffering from increasing financial trouble following poor marketing decisions and a failure to meet production targets. To augment its range-leading but costly-to-make 750cc triples, the appeal of its traditional six-fifty twins was expected to be enhanced by upgrading them to full-size seven-fifties, the final step in a design that had been launched before World War II as a 500.

As the owner of an old Triumph 6T Thunderbird, I was eager to discover what they were like and in mid-January 1973 took delivery of a Tiger 750 TR7V, the single-carb version of the Bonneville. Perhaps I was biased, but I thought the new five-speed 744cc (76 x 82mm) twin was great. The lusty engine had a broad power range peaking at 49hp@6,200rpm and with a weight of just 186kg with a gallon of fuel was nimble and sure-footed, even on the slimy roads of late winter.

More remarkable was that I reported “almost no vibration at 110km/h” when all could be heard from the new-style silencers was a subdued hum. At that speed the Tiger returned a fuel consumption figure of 4L/100km. Better still was that with a standing quarter mile time of 13.80 seconds and a terminal speed of 152km/h, the Tiger was quicker than the previous year’s 650cc four-speed Bonneville. The Tiger’s top speed – a mean from two opposed runs – was 182.6km/h. (Later that year in June I also tested the twin-carb T140V Bonneville which was otherwise identical. Its top speed was the same but its acceleration was slower at 13.95s and 151km/h. How the mighty had fallen).

Norton was due to launch its new 850 Commando range on 10 March when Motor Cycle was publishing a special edition in which road tests of the whole range would be included. First up was the 750 Roadster which, tested in mid-February just two weeks after the Tiger 750, showed how refinements had improved on the unreliable 750 Combat-engined model of a year earlier.

Norton was due to launch its new 850 Commando range on 10 March when Motor Cycle was publishing a special edition in which road tests of the whole range would be included.

Changes to the 745cc (73 x 89mm) twin for 1973 included higher-duty roller main bearings, a lower 9-to-1 compression ratio and, for the European markets, raised overall gearing by using a bigger 21-tooth gearbox sprocket. Yet peak power remained a claimed 60hp@6,800rpm, and top speed at MIRA was barely 2km/h down at 187km/h. But the test track was too wet to obtain meaningful acceleration figures, so two weeks later I brought the bike back when we were testing the 850 Interstate. Standing quarter mile figures for the 201kg 750 were 13.5 seconds with a terminal speed of 160.2km/h, and were up with the best at the time. I’d reckoned that was enough to make the bike a showroom winner, what with refined and smooth manners at speed thanks to the Isolastic rubber engine mounts, along with fine roadholding and handling. But the 850 was better.

With 828cc obtained from a 77mm bore, the 850 made the same 60bhp peak power but 6,200rpm. On the same gearing as the 750 it could rev out better, reaching 194.2km/h flat out, making it the fastest Norton ever tested by Motor Cycle.

With 828cc obtained from a bigger 77mm bore, the 850 made the same 60bhp peak power but at lower revs, 6,200rpm. And on the same gearing as the 750 it could rev out better, reaching 194.2km/h flat out, making it the fastest Norton ever tested by Motor Cycle. With a quarter mile time of 13.2 seconds at 160.2km/h, the 850 made light of its high performance while for touring the almost six gallon tank offered a range of more than 250 miles, even at high 150km/h cruising speeds.

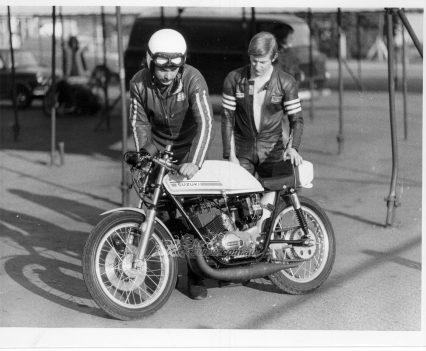

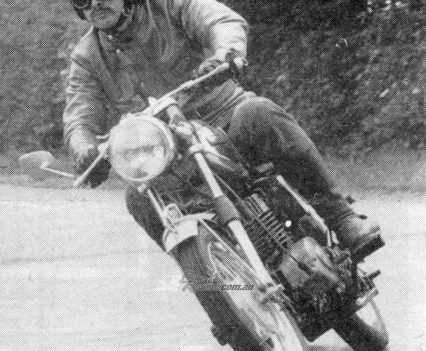

Testing bikes at MIRA was just part of the job at Motor Cycle, which also included general reporting. So in January I had ridden to the Eiffel Mountains in Germany to cover the Elephant Rally on the paper’s long-term test BMW R75/5, and wrote my impressions of a 125cc Rickman Zundapp enduro bike, embarrassing myself by having a go in an observed trial. Big mistake, but enough of that. In April I also had a spin at Brands Hatch on a Suzuki Clubman 250cc racer that was being marketed as an entry-level machine by racing dealer Geoff Monty. It was tuned by none other than Stan Stephens.

That BMW was a surprise, because when we took it to MIRA to test it with 6,850miles on the clock it recorded a top speed of 181.5km/h, not far short of the Triumph Tiger, and a standing quarter of 13.9s at 153km/h. Pretty good for what was a supremely refined and comfortable tourer.

Soon after I put in a lot more miles on a 1973 R75/5, during BMW’s Maudes Trophy attempt in the Isle of Man to celebrate the factory’s 50th anniversary. The idea was have two machines ridden around the TT circuit for seven days with stops only for fuel and servicing, all under the scrutiny of ACU stewards, to demonstrate their reliability. Despite crashes and other problems, the bikes each covered more than 8,000 miles and BMW won the trophy, but that wasn’t my most lasting memory of the event in which I clocked 39 laps of the TT course, day and night. Best was being in a friendly team that included racers Mick Hemmings and Tony Jefferies, journalists Pete Kelly, Charlie Deane, Mike Nicks, John McDermott, Allan Robinson and Bruce Preston, TT chief travelling marshal Allan Killip, and all under the leadership of ISDT ace and BMW dealer Ken Heanes.

After the TT in June (notable for Jefferies’ production race win on the ‘Slippery Sam’ 750 Triumph triple and Peter Williams’ F750 win on the factory Norton), testing resumed. Three bikes were taken to MIRA: the Triumph Bonneville mentioned earlier joined by the unlikely two-stroke pairing of the new Suzuki GT185 twin and an East German MZ TS250 single.

The Suzuki, with its 184cc five-speed engine, Ram-Air cylinder head and self-starting generator, showed off the latest in Japanese two-stroke technology, in contrast to the MZ’s East German simplicity, with its rubber-mounted four-speed engine and drum-braked 16-inch wheels. Yet both were refined in their own ways, and offered almost identical performance, the MZ clocking 131.8km/h, the Suzuki 128.1km/h. Acceleration was much the same as well, the Suzuki quicker at 18.05s at 112.6km/h, the MZ with 18.3s at 114.1km/h.

Yamaha racing stock had been riding high in 1973, with Jarno Saarinen winning both the Daytona 200 and Imola 200 races on a TZ350 twin. In the 500cc class of the GPs, Saarinen even beat the MV Agusta of Giacomo Agostini with the new Yamaha four before he passed in the Monza tragedy.

Launched for 1973 was Yamaha’s latest reed-valve two-stroke twin range, called quite justifiably RD, for Race Developed. UK importer Mitsui Machinery Sales first provided the RD200 (also known as the CS5E), which was like the GT185 with its self-starter but much more lively. With 22hp@7,500rpm, the 116kg machine was good for 142.4km/h and zipped through the quarter mile in 17.6 seconds, terminating at 119km/h. It also looked great with its seemingly massive 2LS front drum that was great for performing stoppies.

Check out our RD350 feature here…

But what many of us were gagging for was the RD350, the road version of Yamaha’s amazing TZ350 racer. The test bike certainly looked the part, with its frame, suspension and basic engine components almost the same as the racer’s, topped off with deep maroon paint for the tank and side panels. Power of the air-cooled twin was up compared with the previous YR5, at 39hp@7,500rpm and with a weight of 156kg with a gallon for fuel was no heavier than the average two-fifty.

The German-market model provided for testing had its sixth ratio in the gearbox blanked and the final drive adjusted to more easily meet UK noise regs, which is possibly why it clocked only 166.2km/h flat out. And the acceleration might have been better than the 14.45 seconds, terminating at 142.4km/h. But its handling was brilliant, making it the bike to beat on twisty back roads. That bike, reg no RYN51L, survives, being owned by Dave Higgins in Southampton.

“The high spot of the 1973 tests was undoubtedly Kawasaki’s Z1, powered by a mighty 903cc double-overhead-camshaft four-cylinder engine developing 82hp@8,500rpm.”

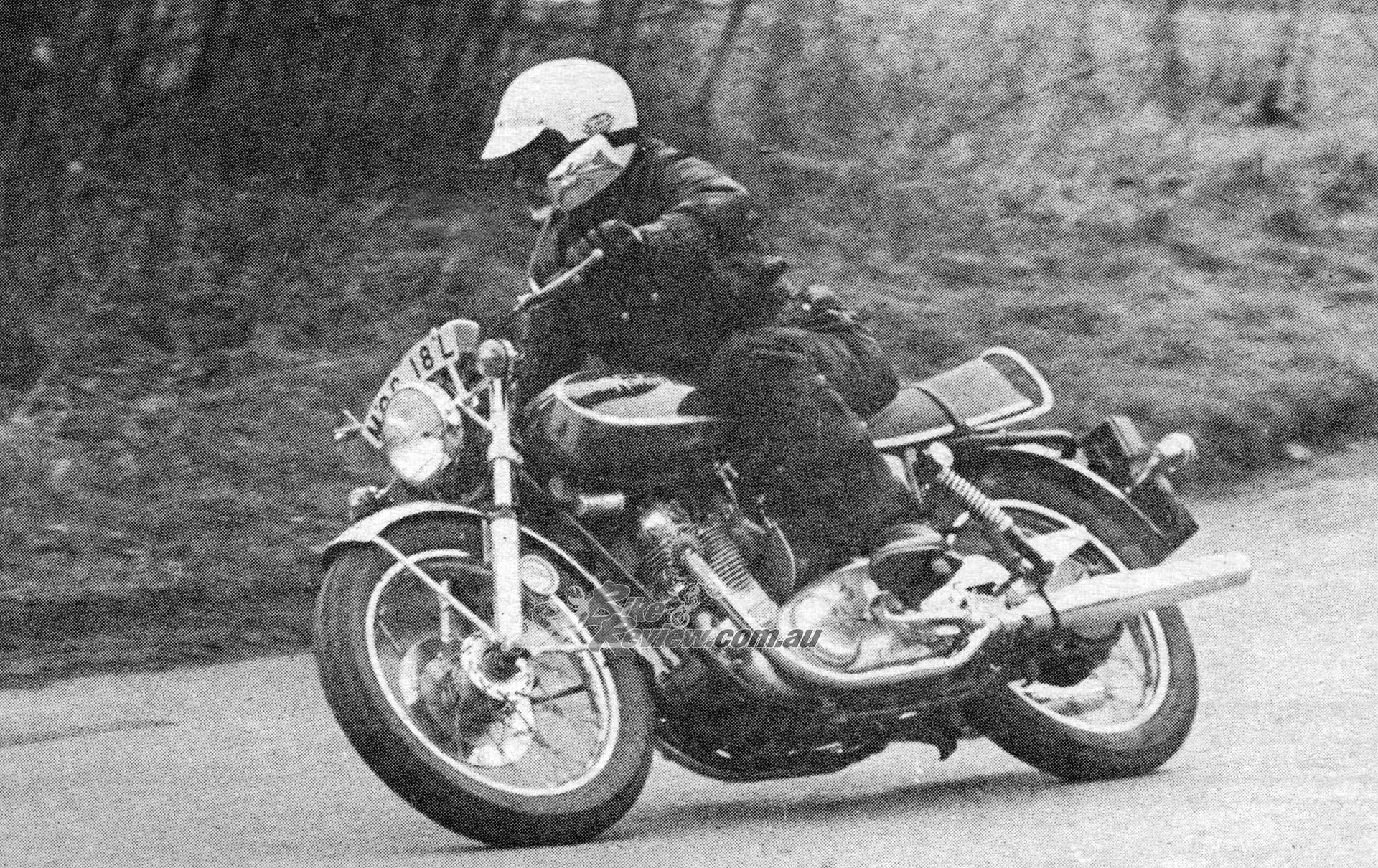

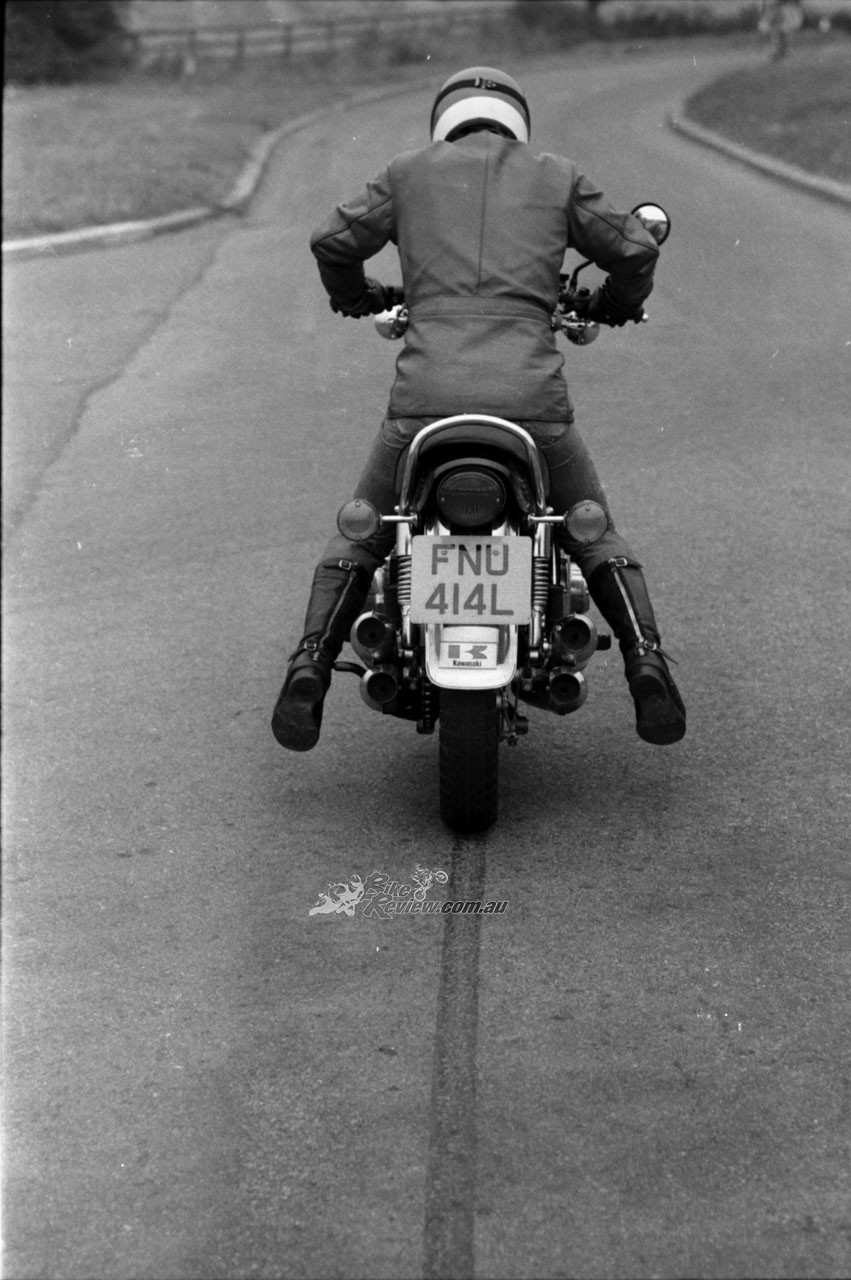

The high spot of the 1973 tests was undoubtedly Kawasaki’s Z1, powered by a mighty 903cc double-overhead-camshaft four-cylinder engine developing 82hp@8,500rpm. That was a clear 11bhp more than Kawasaki’s own H2 750cc two-stroke triple (first shown in 1972 but yet to be made available in the UK) and guaranteed the Z1’s performance supremacy.

My first encounter with the Z1 had also been in August 1972 when Dutch importer Henk Vink invited me to try out the first pre-production machine to arrive in Europe, so I had an idea of what the cliché ‘an iron fist in a velvet glove’ really meant.

It was a dazzling day at MIRA in August with the horizon shimmering in the heat. Unleashing the beast on the timing straight, my accepted ideas of performance were turned on their head. Just to get the feel of the Z1, I wound it up while sitting like a sack of potatoes and it still clocked 188.2km/h. After a couple more runs using my flat-track prone stance it peaked at a two-way average of 210km/h. Average standing-start quarter miles were rattled off with disarming ease at 12.55s at a terminal speed of 173.1km/h. Yet the Z1 would trickle along at 30km/h in top gear and still pull away smartly. As we all know, the Z1’s high-speed handling was wanting, but that just seemed to be part of what became the legend. That first Z1 was an unforgettable experience.

“It was a dazzling day at MIRA in August with the horizon shimmering in the heat. Unleashing the beast on the timing straight, my accepted ideas of performance were turned on their head.”

Of more practical importance to me was the reed-valve Yamaha RD250 twin tested two weeks later. With a mean top speed of 151.2km/h this was one of the quickest quarter-litre road bikes ever (and yes I knew about the reputation of Ducati’s desmo and Suzuki’s X6) with more potential when its six speeds were available. I liked the test bike so much I bought it to go production racing.

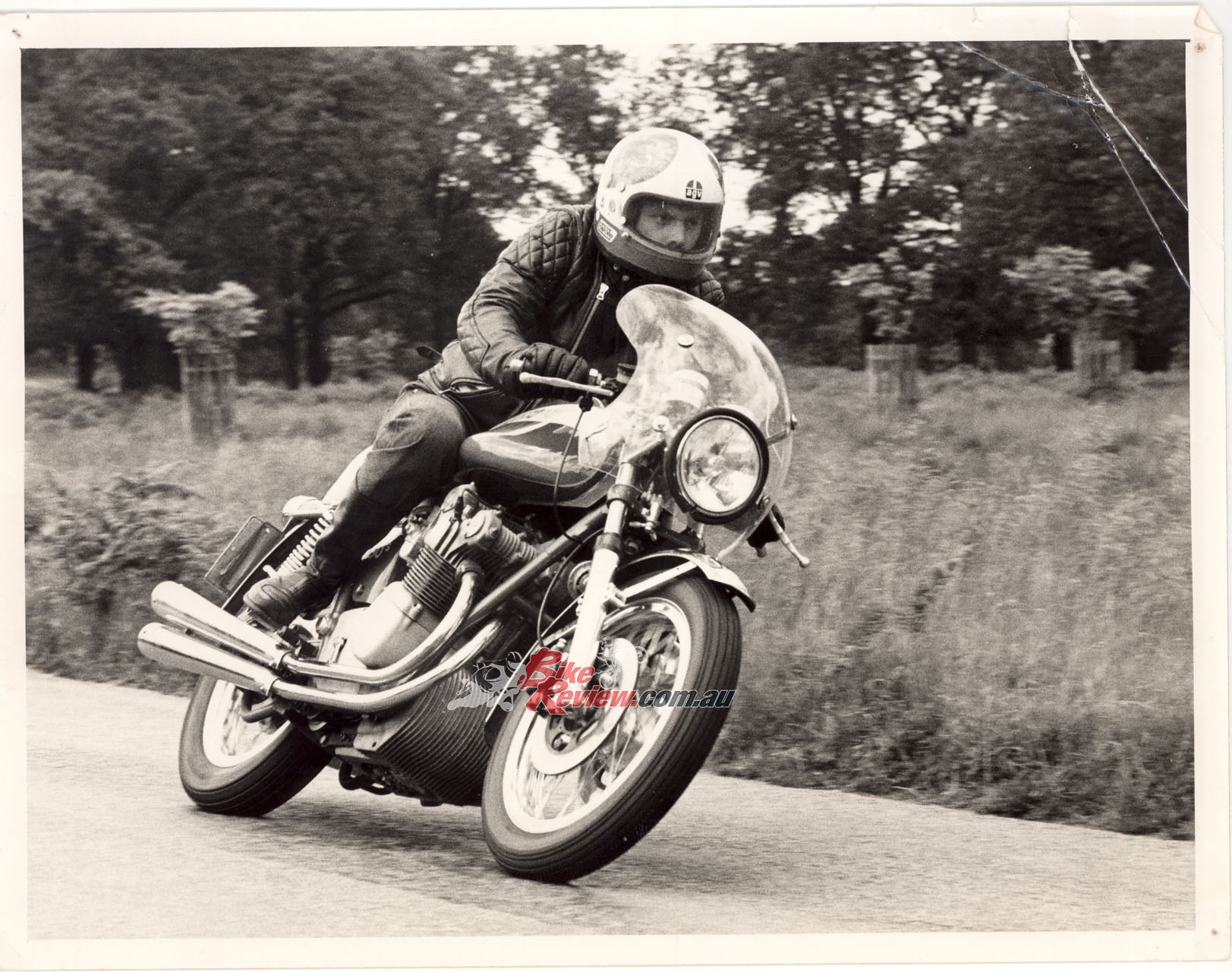

We’d also built a good relationship with Laverda importer Slater Brothers and the next test bike, a 750SF OHC twin, the first of four Italians to be put through their paces. Big and beefy, the stretched-out 750SF was made for high-speed road work and was notable at the time for its huge drum brakes and light-alloy rims.

“Big and beefy, the stretched-out 750SF was made for high-speed road work and was notable at the time for its huge drum brakes and light-alloy rims.”

With a claimed 65hp@7,000rpm, the Laverda promised much more than a big British twin but with an average top speed of 183.2km/h it was only on a par. Acceleration was also down on the Brits with a time of 14.15s and a terminal speed of 152km/h. When we weighed the bike on MIRA’s scales we found out why. With a gallon of fuel the 750SF came in at 226kg, against the Triumph’s 187kg.

“With a claimed 65hp@7,000rpm, the Laverda promised much more than a big British twin but with an average top speed of 183.2km/h it was only on a par.”

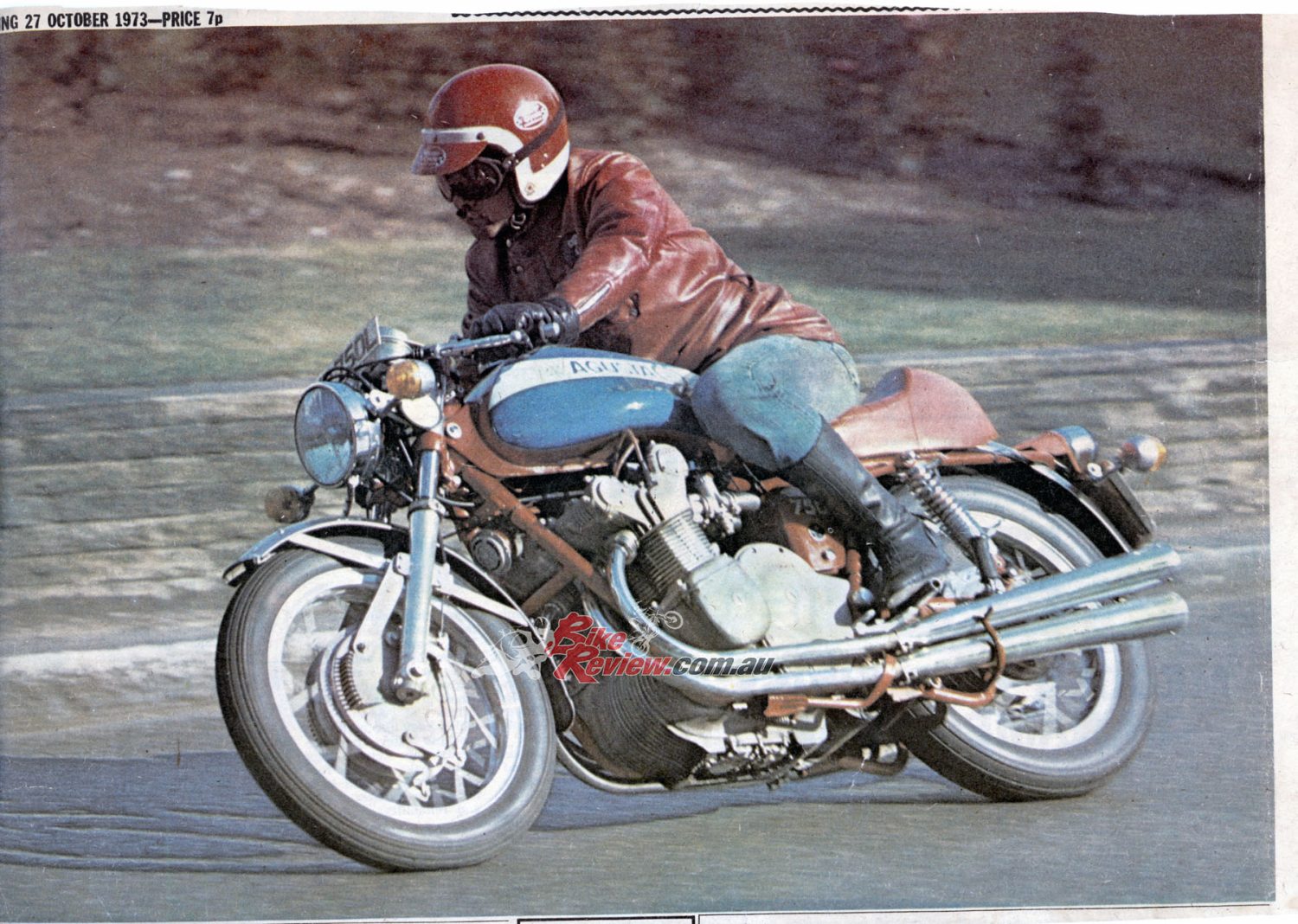

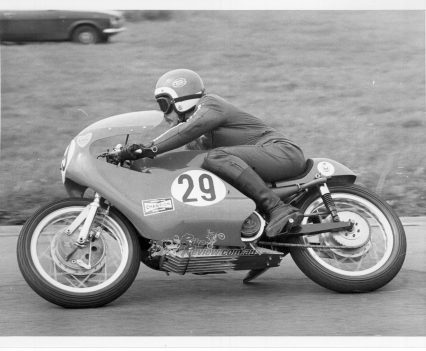

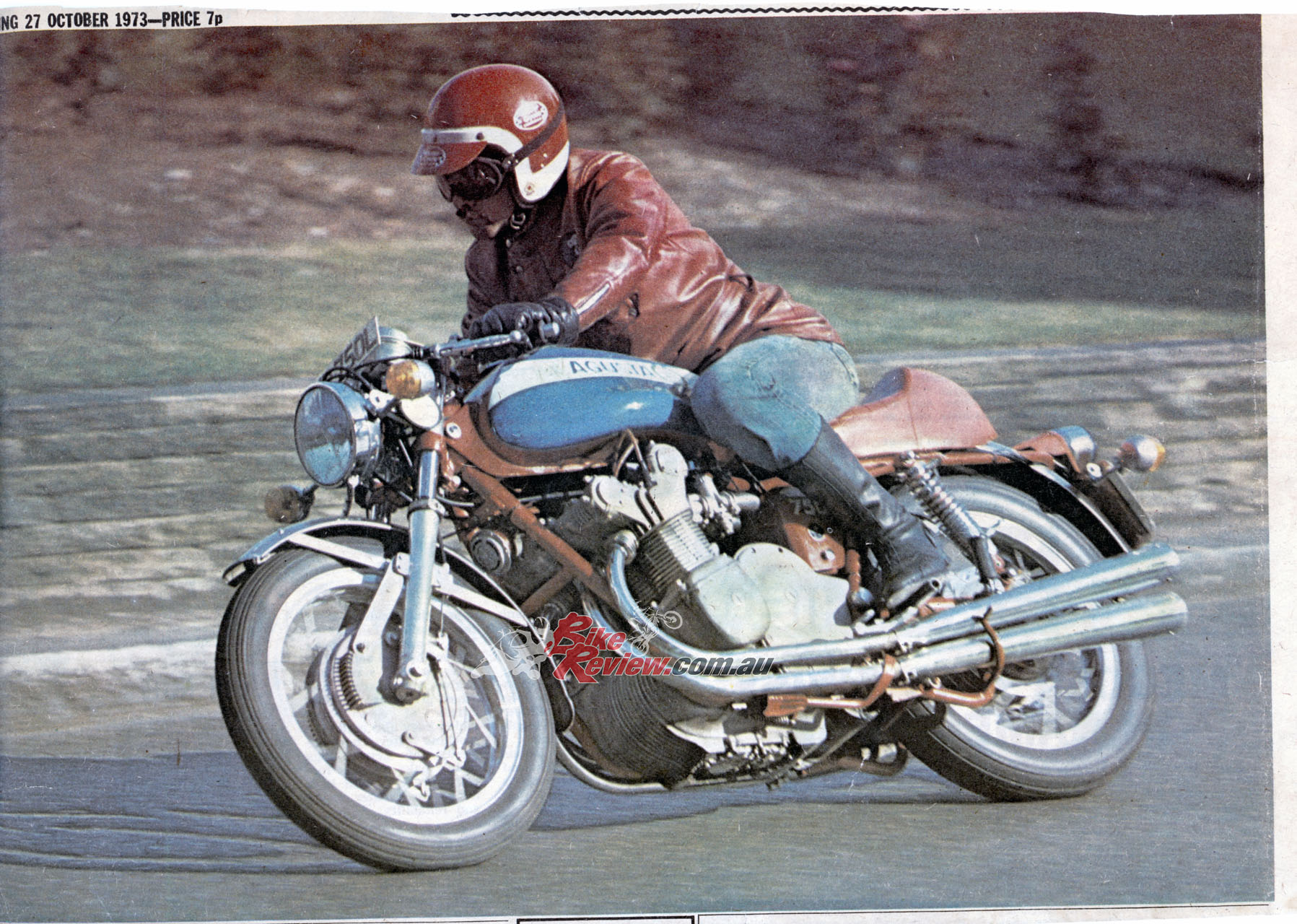

Then I had one of those strokes of luck that don’t come every day: a call from Chris Meek, the owner of Mallory Park circuit at the time. Would we like to test his latest bike, an MV Agusta 750 four? About exotic as a bike can get and rare as hens’ teeth, the red and blue MV was a crowd puller wherever it was parked. It was wonderful to ride as well, with its spine-tingling cacophony of gear whine and exhaust roar enveloping the rider crouched over the clip-on bars with their silky Italian controls.

About exotic as a bike can get and rare as hens’ teeth, the red and blue MV was a crowd puller wherever it was parked.

But despite a claimed 65hp@7,900rpm, the MV wasn’t that fast, topping out at 180km/h and with a quarter mile time that could be bettered by a two-fifty. Again its 230kg weight was against it. Not that it mattered: the MV looked like a million dollars.

From one end of the scale, a pair of Italian lightweight two-strokes from Benelli were at the other. Outwardly identical, the 125cc and 250cc twins provided a fine handling contrast to their Japanese equivalents, even though their performance wasn’t that great, topping out at 111km/h and 143.2km/h.

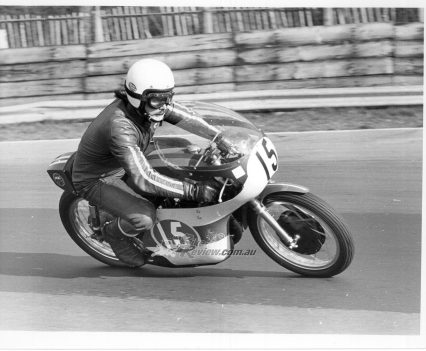

By now it was late Autumn and the weather at MIRA was becoming a gamble. So getting the best from bikes on a wet track in gusty conditions wasn’t my preferred choice. None the less, an invitation to test a special Norton Commando tuned by south London dealer Gus Kuhn was too good to be missed. The bike, an 850 Roadster, had been uprated using specifications developed by the factory’s experimental engineer John Baker and tested by factory rider Dave Rawlins in the heat of drag racing.

Despite a claimed 65hp@7,900rpm, the MV wasn’t that fast, topping out at 180km/h and with a quarter mile time that could be bettered by a two-fifty.

With camshaft and cylinder head mods, the tuning had produced 66hp@6,250rpm, and the Gus Kuhn 850 delivered the goods with a mean top speed of 202.6km/h and a quarter mile time of 12.7 seconds at 166.3km/h. But this was with standard gearing and the engine would easily over-rev to more than 7,000 in top gear. What would it do with a bigger gearbox sprocket? I found out a week later with the machine suitably modified: though the mean top speed was unchanged (the gearing was now too high) with a tail wind it clocked an amazing 218.2km/h one way.

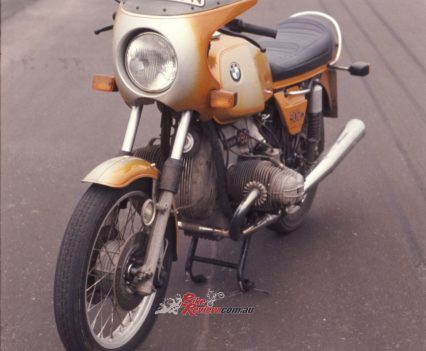

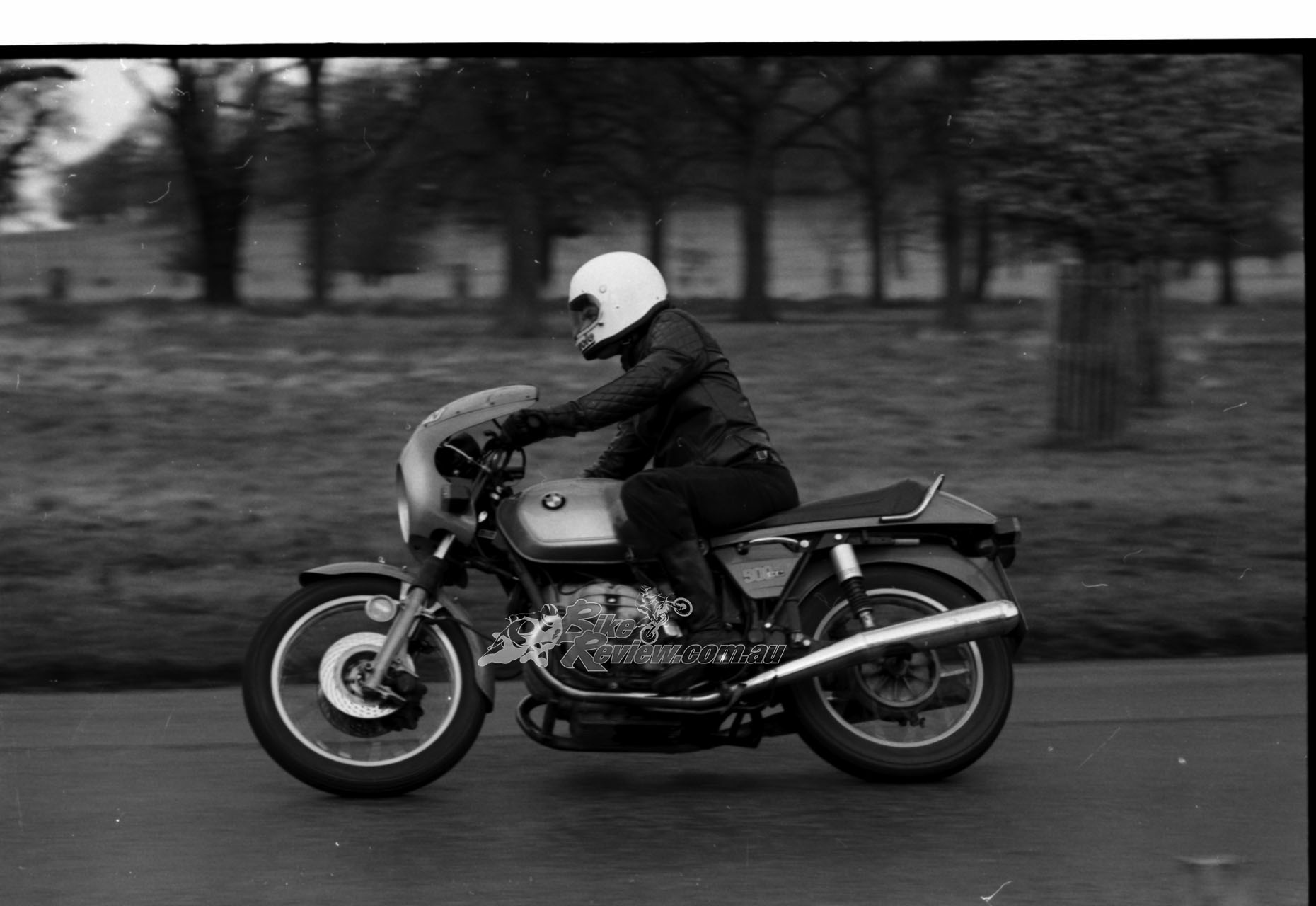

From the ridiculous, next up was the sublime with BMW’s new range-leading R90S boxer twin. Though it was wet and windy at MIRA, the bike’s hot pots and cosy fairing made high-speed cruising a breeze. Smooth and refined, the Berlin boxer flew up to 202.7km/h with a tail wind, and I’m sure that the two-way average of 188.6km/h would have been improved in more clement conditions.

In perfectly crisp conditions, the R90S zipped through the lights at a mean 192.3km/h, and clocked 13.45 seconds at 161.7km/h through the quarter mile. And all without raising a sweat.

That assertion was supported by the performance of the unfaired BMW R90/6 a fortnight later. In perfectly crisp conditions, it zipped through the lights at a mean 192.3km/h, and clocked 13.45 seconds at 161.7km/h through the quarter mile. And all without raising a sweat.

The weather was worse when I took Norton’s updated 850 Roadster for its late-November appointment with destiny. To meet tougher German noise regs the MK2A featured annular-discharge silencers, a bigger airbox and higher gearing, all of which dented performance. With the temperature just above freezing and snow dusting across the track the Norton could only manage 181.5km/h, so I abandoned the test and returned six days later. While the bike clocked 183.4km/h it was still damp, which reduced grip, so the quarter mile time of 13.8 seconds was the best it could manage.

I’d have liked a better climax to the year, but then there had been some other amazing machines to sample, such as Jerry Lancaster’s phenomenally quick four-cylinder two-stroke 680cc Konig racer, similar to the machine on which Kim Newcombe had been runner up to Agostini in the 1973 500cc GP series., Charlie Williams’ Maxton Yamaha TT racers and, to show that life then wasn’t all about performance, Yamaha’s FS1E and Honda’s SS50Z. What a year. And there was better to come.

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.