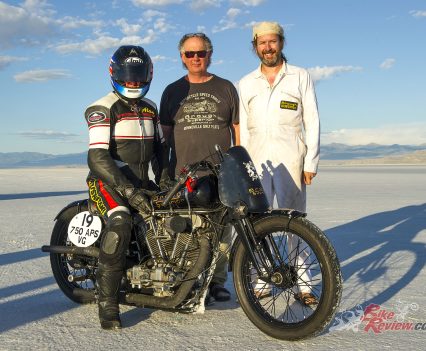

Brough Superior are known for their pre-WW2 record breaking bikes. AC recounts his place in the history books after he took the 750cc Baby Pendine to Bonneville... Photos: Phil Hawkins

Brough Superior, founded in 1919, was the so-called Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles, the manufacturer of the world’s fastest, most desirable and exclusive motorcycles in the pre-WW2 era. Just days after the 2023 event was cancelled, we look back at Alan’s record ride.

Brough Superior, founded in 1919, was the so-called Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles, the manufacturer of the world’s fastest, most desirable and most exclusive motorcycles in the pre-WW2 era. AC Set some world-records on one!

Read our other Throwback Thursdays here…

Sadly the 2023 Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials have been cancelled owing to the after-effects of Hurricane Hilary, the tropical storm which devastated Southern California and NW Mexico over the weekend, which spilled over into Utah and Nevada, bringing heavy rainfall in its wake and forcing the last minute cancellation of this years’ BUB event. You can read the full statement here…

Only 3,000 pre-WW2 bikes were made before the company ceased production in 1939 with the advent of war, and began making parts for the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine powering the historic Spitfire fighter aircraft. Holder of the World Land Speed Record for motorcycles for much of its 21 years of existence, Brough Superior had swiftly built a formidable reputation for itself under the direction of its founder, George Brough, based on a winning combination of unrivalled performance, dazzling looks, competition success, and clever marketing.

Brough did not resume production of motorcycles after the war ended, but that’s since changed under the direction of its current owner Mark Upham, the Austrian-based Brit who acquired the company in 2008, and since then has been building brand new examples of the iconic 1930s SS100, which in many ways was the first true Superbike, and in the vintage era became the motorcycle of choice for cognoscenti of speed.

Read more about Brough Superior’s 2021 revival here…

These included the legendary T.E. Lawrence (‘of Arabia’), who owned seven Broughs in succession before he sadly died riding one in 1935. Upham is back-ordered in manufacture of his vintage-style SS100 recreations, authentic down to the smallest detail – but with the benefit of electric start!

Upham has also facilitated the relaunch of Brough Superior with a range of modern high-performance, high-quality and inevitably high-priced V-twin models built in France, by leasing the name to Toulouse-based Thierry Henriette, who since 2015 has produced a range of bikes bearing the hallowed BS badge powered by a 997cc DOHC eight-valve 88° V-twin motor especially developed for the brand.

But exactly ten years ago in 2013, while in the process of cementing the deal with Henriette, Mark Upham was at pains to remind today’s customers of Brough Superior’s glorious history as a prestige brand by re-establishing its record-breaking credentials at World level.

Henriette was part of the development of the Fior Bol d’Or racer, you can see the influence of the Fior front-end with the revived Brough Superiors. Read more here…

“We are looking to revive the reputation of Brough Superior not by legend, but by deed,” he said. “You can’t appreciate the future without being mindful of the past, and our intent is to remind the public what this marque represents.”

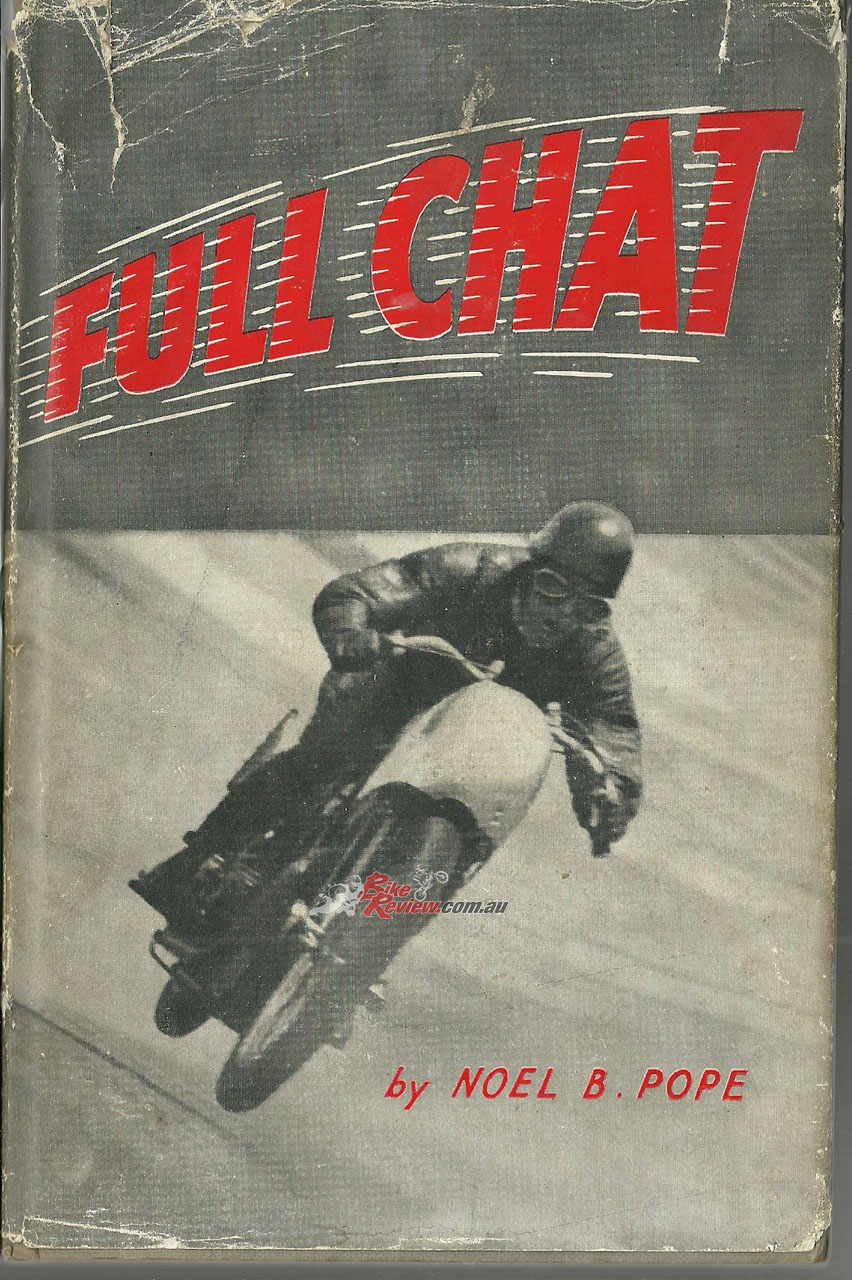

In any case, Brough had unfinished business at Bonneville, ever since Noel Pope, Brough’s motorcycle lap record holder on the pre-war Brooklands bankings, went to the Salt Flats back in 1947 with a streamlined Brough Superior, but sadly suffered a high speed crash on his very first test run. Though he wasn’t badly hurt, the project had to be abandoned.

Hence the invitation I received to ride for the factory Brough Superior team in the BUB Bonneville Speed Trials in August 2013. Under Mark Upham’s ownership, Brough had already made an exploratory foray to Bonneville in 2011, when rider Eric Patterson broke the existing AMA 1350 A-VG Vintage record by running at 124.98mph on an 1931 Brough Superior 1150cc Pendine – the marque’s most potent model back then, named after the South Wales sands which were Britain’s pre-war equivalent of Daytona Beach as a venue for the pursuit of speed.

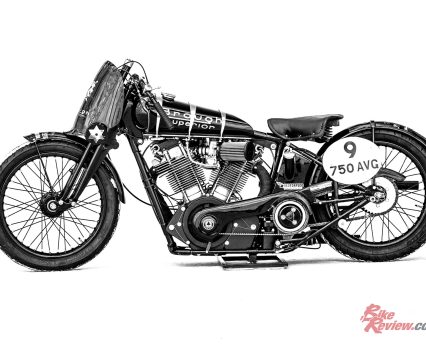

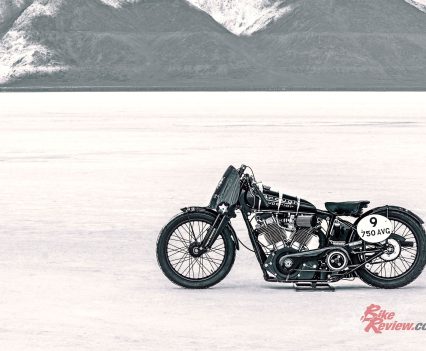

But for a much more high profile return to the Salt Flats the following year, Upham decided to up the ante with a two-bike team by building what he christened a Baby Pendine for the 750cc class, using a 50° V-twin OHV JAP motor from the same engine manufacturer as the bigger Brough.

Read the full Tech Talk on the Baby Pendine 750 here…

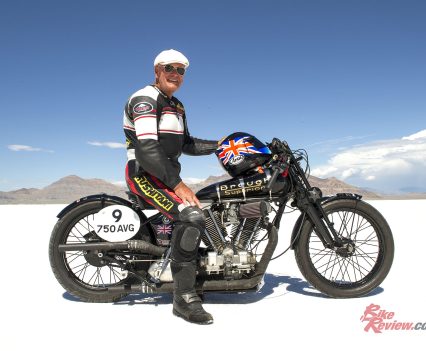

Patterson would return on the bigger model, now with some very period-looking streamlining to allow it to compete in the Partially Streamlined category, while I’d join him to ride the smaller engined bike in pursuit of the AMA’s 750 A-VG Mile record. Once I’d unscrambled the alphabet soup this turned out to be the class for Unstreamlined bikes using an engine built before 1956 on pump gas, for which the record was open.

But there was better yet to come, for as a reward for carefully reading the FIM’s rule book I discovered there were as yet no Unstreamlined, Normally Aspirated outright World records for the flying mile and flying kilometre set for the 750cc twin-cylinder category which the FIM had introduced five years earlier. So we entered the vintage Brough for these, too, more in hope than the expectation that nobody with a much more modern Ducati or BMW would turn up at Bonneville, and grab them instead.

TV bike journalist Henry Cole would also ride ‘my’ bike in pursuit of the AMA’s 750 A-VF record, but this time using racing fuel, in hoping to film a successful record grab in the episode of his British TV series The Motorbike Show that he and his film crew were shooting at Bonneville. If all went well and we both got our records, the idea was for me then to try to break the AMA’s 750 APS-VG Mile record for Partially Streamlined Vintage bikes held by a Harley-Davidson at 108.931mph, with the aid of a token piece of aluminum wrapped around the Brough’s forks which would serve to meet the class requirements. Getting that would be the icing on the cake….

OK, so much for the paperwork – now what about the bike? Well, construction of this was assigned by Mark Upham to super-capable race engineer Sam Lovegrove, a Cornwall resident whose CV includes designing transmissions for Honda and Corvette Le Mans 24-hour racers, in between fettling his array of vintage Ariels. After a three-year stint as Head of R&D for Europe’s largest Hydrogen Fuel Cell developer, Sam retired to his well-appointed Cornish garden shed to build Vintage motorcycles – including ‘my’ Brough.

Construction of this was assigned by Mark Upham to super-capable race engineer Sam Lovegrove, a Cornwall resident whose CV includes designing transmissions for Honda and Corvette Le Mans 24-hour racers.

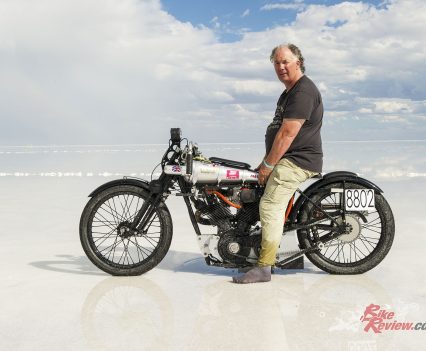

This was concocted using a Brough Pendine chassis dating from 1927, which would originally have housed a big 1150cc JTOR motor, but for our Bonneville bash instead carried a Lovegrove-tuned 750cc V-twin JAP engine, one of a small batch produced in 1954 of around 30 special race motors which the British engine manufacturer built for the Italian 750cc race formula that produced such an array of Etceterini racing car brands in the immediate postwar era.

Bandini, Moretti, Siata, Giaur, Abarth, Giannini were a few of the 84 different constructors of 750cc racing cars to compete in the Italian National Championship races. This engine had been discovered some years earlier in a storeroom in the recesses of the Scuderia Ferrari race shop in Maranello – strange, but true! – before Mark Upham acquired it for this project.

Sam Lovegrove had the complete Baby Pendine up and running by early in May 2013, a week before he brought the unpainted bike to Turweston Aerodrome near Silverstone for what in the world of bespoke tailors they call a fitting – as in, would Sir like to show a little more cuff, and is the inside leg measurement comfortable for Sir?

I was more concerned about the shape of the voluptuously curved handlebars, because it’s one thing to have the grips aimed at the salt for maximum wind-cheating effect, quite another to have sufficient control of the bike to point it at the horizon with the throttle wide open, while still able to stop a slight weave becoming a full blooded tankslapper, should the salt be a little slushy. But Sam had done a good job in combining the two, and I only had a few minor requests for improvement, plus even running at 80 per cent throttle down the airfield runways, it seemed as if the baby Brough had loadsa mumbo – much more than I’d expected from this vintage era motor. Lookin’ good!

Fast forward three months later to August, and my sixth visit so far to the Bonneville Salt Flats for my latest hit of that satisfying white substance called salt. No doubt about it – the pursuit of speed becomes completely addictive, and I’d become totally hooked after a three-year learning curve spent on the Salt Flats aboard the tuned-up South Bay Triumphs prepared by Los Angeles speed guru Matt Capri, culminating in my grabbing four FIM Land Speed Records on two different bikes in 2009, all of which still stand today, ten years on.

“Fast forward to August and my sixth visit so far to the Bonneville Salt Flats. The pursuit of speed becomes completely addictive, and I’d become totally hooked.”

So I’d been looking forward to returning to Utah again that year for the 2013 BUB Motorcycle Speed Trials aboard the Brough Superior, and it was with a sense of optimism that I tooled down the I-80 freeway from Salt Lake City to Wendover, Utah in late August, heading into the sunset to meet the Brough Superior team.

They’d driven the 11-hour haul up to the high desert from Los Angeles with the bikes, after uncrating and prepping them in TV star Jay Leno’s industrial-sized Big Dog Garage – Jay was a satisfied customer of Mark Upham’s several times over, and he made the team very welcome, even down to hosting a reception for us in conjunction with the Ace Café in the rooftop garden of the Petersen Car Museum on Wilshire Boulevard. Great to have well-connected sponsors….!

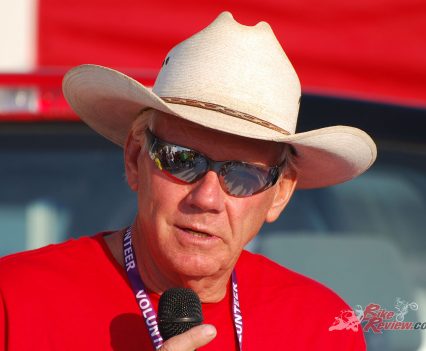

Celebrating their tenth year of running in 2013, the bike-only BUB Speed Trials were the brainchild of larger-than-life Denis Manning, aka BUB – as in, Big Ugly Bastard! The creator of the Harley-Davidson streamliner that conveyed Cal Rayborn to the motorcycle land speed record in 1970, Manning also built BUB Racing’s Seven Streamliner powered by his self-designed turbocharged V-4 motor producing over 500bhp at the rear wheel, which held the record from 2006 to 2008 and again from 2009 to 2010, the latter after seven-time AMA National champion Chris Carr rode it to a new record of 367.382mph.

Manning reasoned that, instead of being second class citizens at the car-dominated SCTA Speed Trials run three weeks earlier since 1949, bikes needed to have their own week on the Salt, and in 2004 he began running his own BUB Motorcycle Speed Trials – the only Bonneville event officially recognised by the AMA and the FIM. Hence the name for the International Course, the longer of the two 90-feet wide tracks dredged from the Salt Flats, eleven miles in length to accommodate the streamliners, with the much shorter five-mile Mountain Course for bikes running less than 175mph. Which meant us….

Cue a magical morning for the first day of runs, with not a cloud in the sky as the sun’s bright red orb rose over the horizon, and we readied the Baby Pendine for its shakedown outing after driving onto the Salt Flats at 6am just as it was getting light. Remember, apart from repeated dyno runs and around 200 street miles, this was a virgin motorcycle that had yet to be introduced to the search for speed. We had no real idea how fast it would go.

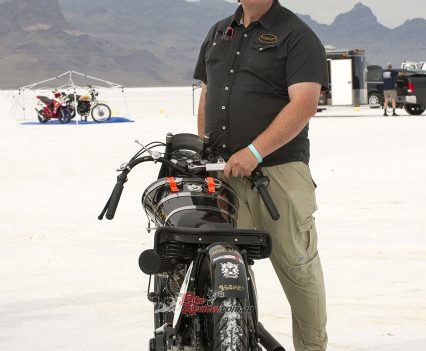

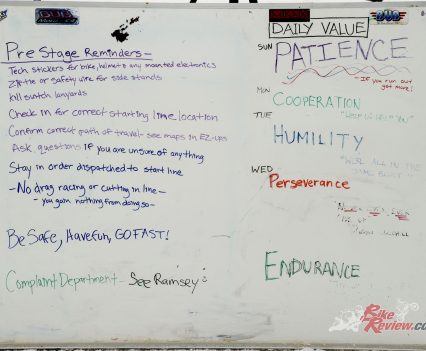

Sam Lovegrove taking the Baby Pendine for a quick lap of the pits before AC takes it for the first shakedown.

The salt was in great shape – “It’s the best yet in our ten years of running here,” announced BUB himself to the crowded riders’ meeting that kicked off the day – with a hard, flat surface and heaps of grip, especially with the humble horsepower figure and hefty weight of our Vintage racer, whose Avon tyres were soon pumped up to 45psi to minimise drag, yet never with any sign of wheelspin.

The riding position is crucial on an underpowered bike, and riding out to the startline three miles from the paddock in a sea of salt, the Baby Pendine’s low, broad seat allowed me to slide back on it so that my thighs were gripping the sides with my bum on the rear mudguard. This let me park the chin of my helmet on the sloping fuel tank, peering between the upright tubes of the Castle forks to see where I was going. But this was only made possible by the shape of the handlebar, whose downward-facing grips were pulled back diagonally towards me.

“The riding position is crucial on an underpowered bike, the Baby Pendine’s low, broad seat allowed me to slide back on it so that my thighs were gripping the sides with my bum on the rear mudguard.”

This allowed me to effectively do a handstand on them, in order to get my torso as low as possible as I draped it across that so-distinctive Brough fuel tank, here painted black rather than nickel-plated as on the BS streetbikes. This wind-cheating stance was pretty effective, especially once I’d finished it off by parking my toes on the ultra-rearset footrests, and squeezing my knees in to the flanks of the fuel tank and beneath my elbows, in search of every last vestige of speed. It all worked – but the most satisfying thing was how well the Brough handled.

It was totally stable at all times, with not a hint of any shimmy or shake, even when I moved my body rearwards as described above, thus inevitably lightening the front wheel, and providing every excuse for a girder forked bike to start doing the Charleston. Only it didn’t.

We chose the shorter three-mile version of the Mountain Course for our shakedown run, and our early start was rewarded with being one of the first to run down the short course, starting at Mile One with a one-mile runup before being timed between Two and Three. Even if it would inevitably count as our FIM World mark, this was just a shakedown run to make sure everything was screwed together OK, so I didn’t bother to tuck away too tightly aboard the bike, and instead concentrated on checking out that everything was fine mechanically.

Which it was, but the one-mile runup hadn’t been enough to attain maximum velocity, meaning I was still accelerating through the measured mile. Still, the speed of 97.260mph for the flying mile (97.447mph for the kilometre) was OK for starters, so I rode straight to Impound in order to make my return run within two hours, as mandated by FIM rules (compared to on the same calendar day for the AMA records).

“We got those two new FIM World records an a two-way average of 101.132mph for the mile, and 101.329mph for the flying kilometre. The mile speed also gave us that new AMA 750 A-VG record too.”

This entailed starting from Mile Five, this time with a two-mile runup to the speed trap between Three and Two – and now I had the Brough tapped right out through the measured mile at 105.004mph (105.210mph for the kilo), delivering us those two new FIM World records an a two-way average of 101.132mph for the mile, and 101.329mph for the flying kilometre. The mile speed also gave us that new AMA 750 A-VG record too. That was worth a cuppa tea in the Brough motorhome to celebrate!

If that doesn’t sound especially fast for even a vintage 750cc motorcycle, keep in mind that power output drops as elevation increases, and with the Salt Flats sitting at 4,291ft/1,308m above sea level, Bonneville poses an extra challenge in countering the 13 per cent loss in power on an unsupercharged engine occasioned by the thinner air at this elevation, even before the as much as 6,780ft corrected altitude for the air pressure prevailing as we made our runs – figure a 120mph top speed for the Brough at sea level (106mph plus 13 per cent) and you’re about right. Now you know why in the old days so many Land Speed records were set at sea level on Daytona Beach – or Pendine – running on the sand with the tide moving out!

However, having banked those Unstreamlined marks for the time being by having the female AMA tech inspector carefully seal the Brough’s engine with copious dabs of her bright pink fingernail polish, we knew we could raise the combined speed by at least 4mph with two good runs, but with no other runners registered for the FIM 750 Twins class, we also knew our new records were safe. So I handed the bike over to Henry Cole who successfully set a new 750 A-VF class AMA record on it of 99.780 mph, despite suffering a massive tankslapper on his return run, caused by the two Go-Pro cameras he’d mounted on the handlebar acting like sails as speed mounted, with predictable results!

He needed to lie down for a while before facing the camera to recount that tale, I can tell you! Then Sam and my son Andrew carefully wrapped the fig leaf consisting of a piece of painted aluminium around the top of the Castle forks, to turn the Baby Pendine into a partially streamlined bike – nominally, at least. But this was the entry ticket to as frustrating a couple of days as I’ve yet spent on the Salt, as we hunted in vain for the missing 3mph which would give us a fourth record.

That return run had been the first time I’d ridden the Baby Pendine really hard, and it had been surprisingly comfortable for a rigid-framed bike – especially thanks to the incredibly smooth engine, which unusually for a narrow-angle 50° V-twin, hardly vibrated at all, at any revs. It’d drive smoothly away from the line with very little clutch slip needed as I drag-raced down the two miles to the timing strip – with the Brough’s pretty lazy acceleration thanks to being geared so high, we needed every last piece of real estate to build up momentum by the start of the measured mile.

“With the Brough’s pretty lazy acceleration thanks to being geared so high, we needed every last piece of real estate to build up momentum by the start of the measured mile.”

I’d rev the engine out to 5,800rpm in the bottom three gears quite readily, but then for some reason it’d take an age to build back up to that mark in fourth, with 5,300rpm the best I ever saw in that gear before grabbing fifth almost in desperation just passing the flags showing one mile to the timing strip. That left the needle on the British Jaeger revcounter parked on the 4,400rpm mark, and struggling to build revs slowly – Sam had perhaps left too big a gap between the top two ratios, and it wouldn’t pull peak revs with that gearing, with 5,100rpm the best I ever saw in top gear through the measured mile, against a safe 6,000rpm maximum.

Of course, we tried gearing it down to try to coax some extra acceleration out of it – but it still wouldn’t pull the revs. OK, let’s gear it up, and try to get the speed in fourth gear. Not either. We advanced the ignition timing forward to 42º to try to counter the effects of altitude, and nor did that work, in fact it definitely made things worse. Yet the engine ran faultlessly throughout the entire week, completing 13 wide-open runs as we searched in vain for that fourth partially streamlined record, with a best run of 105.462mph for what was essentially a naked bike. Close but no cigar….

By now it was the afternoon of Day 4, with just a final half day on Day 5 remaining before BUB 2013 came to an end. Time to remove that fig leaf and make a final pair of runs to raise our FIM records a few mph. Except, except – what’s that huge black cloud heading our way, with shards of lightning crackling through the sky? Short of the Boxing Day tsunami I got caught up in back in December 2005 in Sri Lanka, I can’t think of anything more terrifying than being out on the Bonneville Salt Flats in an electric storm of biblical proportions.

I’ve never experienced a blizzard in Antarctica, but this must have been a warm weather version of that – zero visibility, just white nothingness interspersed by rolls of thunder and flashes of lighting, with sheets of rain that had nowhere to go. The salt is six feet thick, remember, and it’s not porous like normal soil, plus since the Salt Flats are so level, it doesn’t run off, either, just sits there until the sun evaporates it – eventually. Still, it’s certainly an impressive experience, just so long as you have a set of rubber wheels between you and the ground, because remember that salt’s a conductor, and when lightning strikes, it can kill…. Yes, really.

The view that awaited us when the clouds cleared away was literally awe-inspiring, as Phil Hawkins’s lovely photos of what was now Lake Bonneville will confirm. But that was the end of BUB 2013, and in fact it took 23 days for the Salt Flats to dry out, wreaking havoc on the other speed events planned to take place there during September 2013.

But the rain had held off just long enough for the Brough Superior team to add two more records to its haul, for after struggling all week long with a bike that wouldn’t run right, Eric Patterson finally took the 1150cc Pendine to two new AMA Vintage records, the 1350 APS-VF mark at 113.668mph, and with the very last run of the meeting by anyone before the heavens opened, a new 1350 A-VF class record of 124.334mph.

The six new records for Brough Superior represented mission accomplished for company owner Mark Upham.

The six new records for Brough Superior represented mission accomplished for company owner Mark Upham. “We have restarted telling the story that is Brough Superior, and retracing the marque’s footsteps in record-breaking history,” he said. “This is the beginning of a new era for Brough Superior, and with planning in place for our new modern machines, the future looks very exciting.”

On a personal note, I can’t deny the satisfaction – especially as a former Brough owner myself back in the days when you could buy a 1937 SS100 for £1,000, then sell it for twice that, and feel pleased with yourself for doing so (yes, really) that I got from putting one of Britain’s most historic motorcycle marques back in the FIM record books for the first time since 1936, when Brough Superior works rider Eric Fernihough set a new outright Motorcycle Land Speed Record for the flying mile on his streamlined V-twin. 77 years later, I’d joined him in the record books on the Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles. See that flag on my helmet fluttering??! That’s because, almost incredibly, those FIM records are still in the books: https://results.fim.ch/wrecord/wrframe

Brough Superior At Bonneville 2013 Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.