Imagine, you pick the phone up and it's someone asking if you want to ride Rossi's RC211V! See what Mossy thought of the MotoGP machine... Photos: Double Red & Andrew Northcott.

You know an event’s been special when you can trace it right back to its birth; remembering exactly where and when you were at the moment the memory was first triggered, reinforces it as exceptional. In this case, it was the chance to ride Rossi’s Honda RC211V!

It’s not often that you pick up the phone and it’s someone on the other end asking if you’d like to ride Rossi’s bike…

This one began for me during a nondescript Wednesday evening drive home. When I answered my squawking mobile, life instantly changed from grainy black and white, to full HD colour. Honda’s PR chief was a man I knew well, and when he asked a simple question, “do you fancy riding Rossi’s GP bike Mossy?”, sequential chuckling instantly followed. I knew he wasn’t joking. He knew I’d say yes. And so I did. Repeatedly.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

The rest of the trip home became very different; essentially now a much more special journey – from Derby, UK to Cataluyna, Spain. I went from feeling who I was, an ordinary Joe, to someone way more significant. Given the 990cc, V5, 240bhp thoroughbred was going to be like nothing I’d ever sampled before, and especially given the owner was one of the greatest racers of all time, it became obvious I was about to spend time in an emotional zone I’d never visited before. Fuck me, just the prospect of the ride gave me a massive rush.

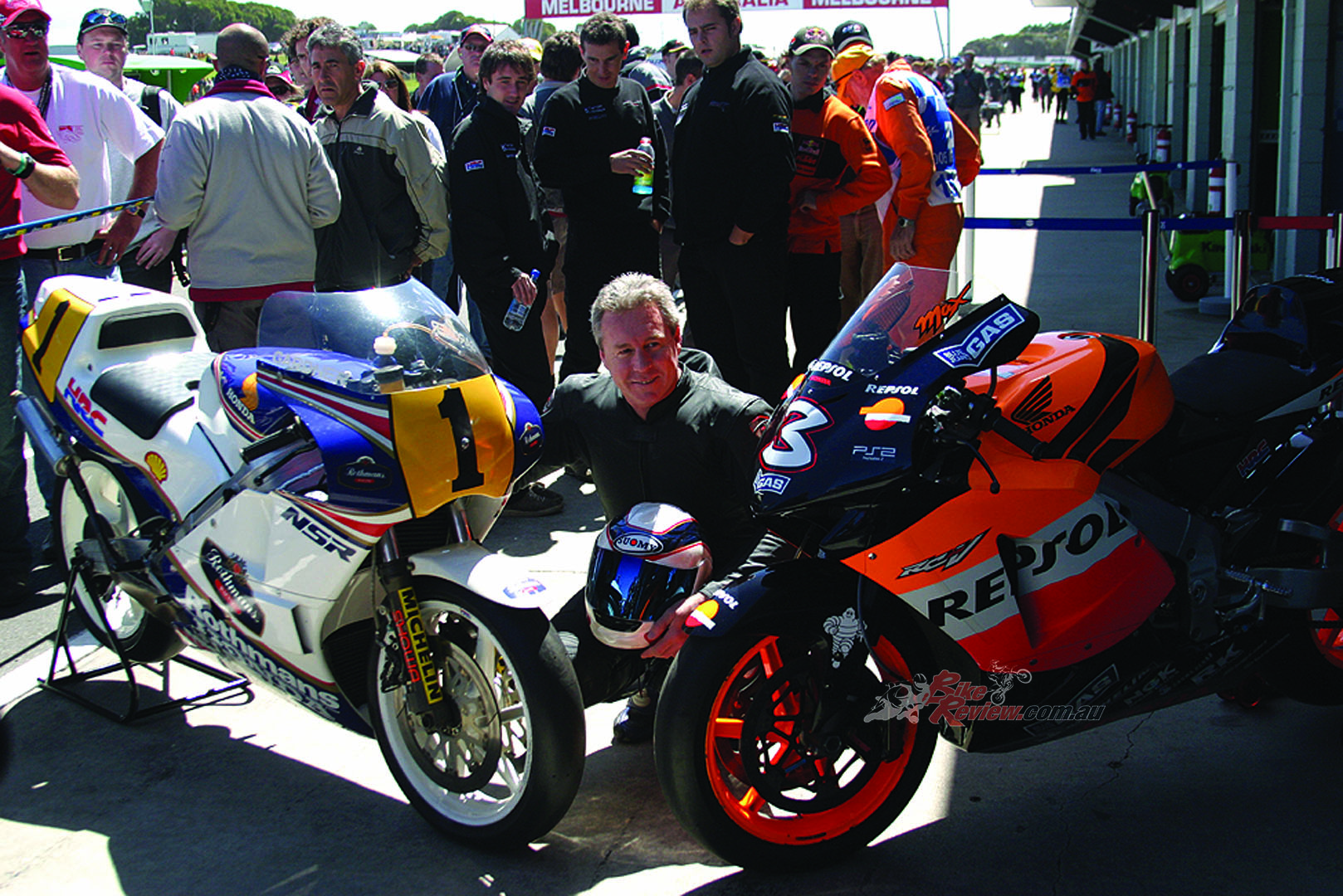

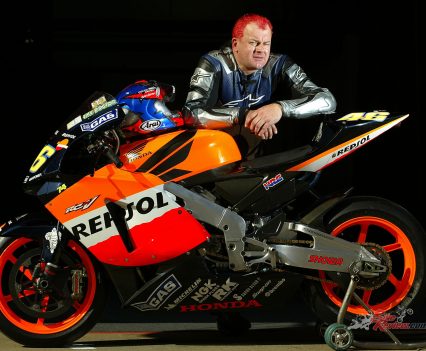

Max Biaggi’s RC211V pictured here, essentially the same as Rossi’s with a few changes in later seasons.

Before I got to fly to Barcelona, Rossi won his second world title on the RC211V, then announced he’d be off to Yamaha the following year. My ride took on even more significance. When I got to the track the day before ride, the gravity of it all hit me like a well-aimed bat.

Check out our test of Rossi’s 2004 Yamaha M1 here…

Colin Edwards, who’d just signed to ride a V5 in the 2004 championship, was testing the Honda for the first time. And the noise of him caning the bike for all it was worth was filling the air. It was a chilling and raucous din, so damned loud you could hear the Texan complete a whole lap from any point round the track. He looked at home on it. I meanwhile, felt terrified by the sight and sound of the V5 monster.

The Repsol Honda V5 marked a new era, with the extremely loud V5 breaking the eardrums of anyone who dared to get close. Wayne Gardner took Max Biaggi’s RC211V for a spin, read about it in an upcoming TBT.

Randy Mamola helped a smidgen by offering comforting words. “It’s just like a fast street bike. It’s really well mannered, and it won’t frighten you a bit. You’ll love riding it and will want to own one straight away.” He seemed very honest and sincere when he said that, so I took his word for it and left the track hoping for the best the next day.

“It’s just like a fast street bike. It’s really well mannered, and it won’t frighten you a bit. You’ll love riding it and will want to own one straight away.” Said Randy Mamola.

The following morning when the alarm call reminded me that the big day had dawned (not that I needed it, as I had been lying awake in fear since 4am), Randy’s words didn’t mean jack shit. Today I was going to be all on my own.

It was time for Chris to rock up to Cataluyna for three laps of glory on one of the most important motorcycles to exist…

At the circuit I learned I was only going to get three laps on the RCV and how vital it was not to crash it. Then the call came to get ready for the big deal. This was it. Time to get on the mother of all motorcycles. I got kitted up and headed to the pit lane. And there it was. The world champion’s steed in all its glory. Closer examination revealed it to be an absolute masterpiece of engineering and every single part of it looked crafted to ensure victory. Compared to this, every other bike I’d seen before appeared somewhat ordinary, though nowhere near as intimidating. Then it was time to ride.

“It didn’t matter I’d been riding all and sundry in the motorcycle world for over twenty-five years, I honestly doubted I could do it.”

An HRC engineer nonchalantly wheeled the starter motor towards the fat rear slick. He nodded for me to get on board. All I needed to do now was wait for the Honda’s rear wheel to be spun up, snick a gear, dump the clutch and fire up the motor. But right then, such was my fear and damage to my confidence I genuinely didn’t think I could even do that simple job. As for getting the RCV underway down the pit-lane and riding it for three laps, my brain delivered apprehension. It didn’t matter I’d been riding all and sundry in the motorcycle world for over twenty-five years, I honestly doubted I could do it.

Despite the huge self-doubt I did manage to get underway and, amid the most ear-bashing cacophony of sound I’ve ever heard from a bike, off I set for my session of uncertainty. The massive torque of the motor means clutch slip isn’t really needed at all to get the bike off the line. Though, with a huge first gear (tall enough, I’m told, to take the bike to over 200kph!) it’s a wonder. After that, even after short-shifting through the first three gears and using very little amounts of throttle, it was patently obvious that this was one amazingly strong engine.

Once I was out on track I gave the twistgrip a slightly angrier tug in fourth and man did the world go backwards! Not quite ready for all of that explosive level of acceleration just yet, I snicked it into fifth and sixth sharpish to let the revs drop and get back to a less frantic pace. Soon after, I needed to brake for the first corner.

Riding a bike with Carbon brakes will catch you out as you come into the first corner of the day and have almost no braking power.

But slowing for the bend didn’t bring much in the way of stopping at all. The carbon brakes weren’t up to full temperature and weren’t very effective at all. Fortunately, I’d grabbed the lever well in advance, thankfully making the corner with room to spare.

Then, just as I’d sussed that out, I had my second serious fright. Steering into the bend made me feel as though the front end was washing out and I was about to get dumped unceremoniously onto the Cataluyna track. Luckily, that wasn’t the case, the feeling of impending doom vanishing as I realised it was just the lightness and speed of how the bike turned that gave me that impression.

“Ten corners later and the reassurance was even more complete, the perfect feel and feedback from the chassis allowing me to get my knee down in total confidence.”

Ten corners later and the reassurance was even more complete, the perfect feel and feedback from the chassis allowing me to get my knee down in total confidence. Not only did I feel physically comfy on this bike, I actually felt mentally comfortable too. Maybe Mamola had been talking sense after all. It says a hell of a lot for the overall balance of the RCV when you can feel at home on it as soon as I did.

“Maybe Mamola had been talking sense after all. It says a hell of a lot for the overall balance of the RCV when you can feel at home on it as soon as I did.”

I still wasn’t pushing it very hard of course, but the Honda wasn’t frightening me anywhere near as much as I’d expected. Then came the big test. And as I rounded the last corner leading to the lengthy start-finish straight I knew I was only seconds away from opening the throttle fully for the very first time. And I really didn’t have a clue what to expect.

Soon it came time to really wind the throttle on, seeing what an early 2000s MotoGP machine is really like.

Tightly gripping everything I could just to stay on board, I feared either flipping the thing or just sliding off the back of it. I shouldn’t have worried. Though the Honda eats rpm, gears and straights in a flurry of flashing rev lights and frantic gear changes, the totally linear and gorgeously turbine-smooth power delivery masks the actual rate at which you’re accelerating. It just feels like an ultra-fast VFR1200-engined roadbike. It really is that friendly, that civilised, that refined.

And so the experience went on. I say it was an experience rather than a test, because I’m not really qualified to give a fully credible account of how this amazing projectile behaves in detail or at its limit. But, as a human being, I feel more than able to pass a judgement on what it does to you when you ride it. And that’s a lot. No other bike I’ve ridden before (including Aaron Slight and Carl Fogarty’s WSB racers) feels anything quite as perfectly sorted as the Honda. Nothing I’ve ridden before stirs the emotions as much.

For someone to jump on a bike and have it cranked over within half a lap shows off the rideability of these machines.

It’s like a big tiger that you can stroke and hand-feed, it’s so friendly. Yet, because it has so much ultimate performance lurking under its fairing, you still have to respect it massively. Just like the big cat, it’ll maul you and take your face off if you don’t. When I did get off it there was a mixture of sadness that it was all over, but relief that I hadn’t dumped it. But more to the point, I had uncontrollable urge to tell the whole world about my brief but incredible adventure. I simply couldn’t stop jabbering for hours about the brilliance of the RCV.

“It’s like a big tiger that you can stroke and hand-feed, it’s so friendly. Yet, because it has so much ultimate performance lurking under its fairing, you still have to respect it massively.”

Nothing about the bike deserves criticism at all. Every single part of it complements the rest of the bike so perfectly it’s almost unreal. And how the likes of ordinary blokes like me can feel so at home on what essentially is a guided missile is almost beyond belief. I’ve been intimidated more by some road bikes since, like Ducati V4 Panigales which, despite their deserved accolades, next to this feel a lot less predictable. There are motorbikes, and then there are RC211Vs. The gap is that big. All the men responsible for creating the V5 deserve huge praise. They’ve crafted a perfect racing tool. It’s no wonder that every GP rider who got the chance to ride one, got good results.

“Nothing about the bike deserves criticism at all. Every single part of it complements the rest of the bike so perfectly it’s almost unreal.”

It’s actually very hard to express your feelings accurately enough to make people fully appreciate what this amazing machine is capable of doing – both on the track, and to your heart and mind. Only if you rode one yourself would you fully comprehend its incredible balance and togetherness. And that’s the beauty of it – anyone can ride it. Not necessarily as fast as Valentino and the others, but pretty quickly and without fear nevertheless.

Looking back, getting the chance to go on the Honda was probably the biggest thing I’ve ever done in my forty-odd years in motorcycling. I only got something like six minutes on it. But that time was so fulfilling I’d be happy to get the chance of just another thirty seconds. And now that I actually know what it feels like, I wouldn’t get anywhere near as terrified as I did before this ride. Thanks to HRC for changing my life for a while. It was an emotional experience, and one I won’t ever forget.

Tune in next month as we revisit Wayne Gardners spin on Max Biaggi’s RC211V…

2003 Rossi’s Honda RC211V MotoGP Racer Specifications

ENGINE: Liquid- cooled, DOHC, 20-valve, 990cc, 75.5-degree V5 four-stroke, 72.3mm × 48.2mm bore x stroke, Multi-injector programmable EFI, digital ignition, Six-speed cassette-type gearbox

CHASSIS: Twin-tube frame, Telescopic forks at the front, unit pro-link rear suspension, twin radial-mounted four piston calipers with carbon discs at the front, Michelin tyres all round, 17in at the front, 16.5in at the rear, 2050mm length, 600mm width, 1130mm height, 1440mm wheelbase, 130mm ground clearance..

PERFORMANCE: 240hp (increased to 256hp in 2004), 148kg wet weight, over 330km/h top speed.

OWNER: Honda Racing Corporation, Japan