A French/Japanese fusion! Alan Cathcart tests this Suzuki GSX110 powered Moto Martin racer around Broadford Raceway. Check it out... Photos: Stephen Piper

The French hearted and Japanese boned Moto Martin Suzuki GSX1100 has found it’s home down-under racing in the heavily competitive Post-Classic Unlimited Period 5 class. I was lucky enough to throw a leg over Scott Webster’s machine at Broadford…

The French hearted and Japanese boned Moto Martin Suzuki GSX1100 has found it’s home Down Under racing in the heavily competitive Post-Classic Unlimited Period 5 class. Alan Cathcart took it for a spin…

The no-holds handlebar-clashing Australian Historic Racing class for air-cooled multi-cylinder monsterbikes officially known as Post-Classic Unlimited Period 5, and by the rest of us as Vintage Superbike, is the most dramatically entertaining and closely fought road racing category anywhere in the world today.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

With 1982 now established as the cutoff year, Historic Racing’s big bike category – there’s a 1300cc top limit to encourage tuners to go large on engine upgrades – recaptures the variety and thrills of Superbike’s early days, when Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki grappled with each other in a titanic struggle for streetbike supremacy.

With 1982 now established as the cutoff year, Historic Racing’s big bike category recaptures the variety and thrills of Superbike’s early days, when Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki grappled with each other for streetbike supremacy.

To make the ride down Memory Lane even more authentic, today’s Down Under version of that spectacle sees many products of the legendary Australian road racing rider factory which it had a hand in rearing, returning to the scene of their crimes against spectators’ nerves. This features the likes of Rob Phillis, Wayne Gardner, Mal Campbell, Marty Craggill and comparative youngsters like Steve Martin and Cameron Donald amongst the stars of yesteryear getting it on again against each other, as well as visiting Brits like Jeremy McWilliams, John McGuinness and Peter Hickman, and the talented crowd of lesser-known riders of all ages in the P5 class.

In keeping with the catch-all concept which the 1980s Swann Series spectaculars adopted Down Under, in matching visiting European riders on 500GP racers and race-framed TT Formula 1 four-stroke behemoths against their Aussie and Kiwi rivals on Superbikes and F750 two-strokes like the TZ750 and KR750, those same bikes today form part of a Post-Classic P5 class that, while simply spectacular in its own right, is also living history on two wheels. Mal Campbell’s pursuit and eventual defeat on an RG500 Suzuki square-four stroker of Honda CB1100 Superbike-mounted Wayne Gardner at the Island Classic not so long ago, was a perfect demonstration of the category’s broad appeal.

Scott Webster with his Moto Martin Period 5 racing machines. Webster is no newbie to racing, funding his own racing career since 1982 and adding the Australian Superbike Championship to his resume in the 1990s…

Amongst these fire-breathing behemoths, no bike is more authentic than Scott Webster’s 1980 Moto Martin Kawasaki Z1R, punched out to 1230cc from its original one-litre format, in which guise the French-framed Endurance racer competed in two editions of the Arai 500 endurance race at Bathurst, before Scott acquired it in 1983, having just started racing the year before. Though his day job as a self-employed auto electrician from Pakenham, an hour east of Melbourne on the road to Phillip Island, has meant Webster could only ever be a part-time Superbike racer down the years, he’s been racing constantly since 1982, and at the highest level from 1985 onwards, in the Australian Superbike Championship, competing with honour in Aussie World Superbike rounds in the 1990s on a Honda RC45. En route to that, Webster raced the Moto Martin for a year to move rapidly up through the grades, before parking it in 1985 once he reached the Superbike class that had just then dropped to 750cc in capacity, making the one-litre French bike yesterday’s papers.

Check out Alan’s feature on the history of Moto Martin here…

“I might have sold the Moto Martin, but I was able to buy a Suzuki GSX750 and run that without needing to raise extra cash by selling it,” recalls Webster. “I’d got attached to the bike, so I decided to hang on to it, and for the next 20 years while I was racing Aussie Superbike, it was a kind of display item in the garage, without ever being ridden. But then a mate of mine said – let’s get this bike out and use it, and go Forgotten Era racing. So I had a few races, and thought – gee, this a whole lot of fun, and there’s a really good bunch of blokes doing it. So from then on I decided to take it more seriously, fitted 17-inch wheels to use modern tyres, and got Trevor Birrell to tune the motor. Things moved on up from there, and we started running at the front, but except for the wheels and the faster engine, it’s still basically the same bike I’ve had for over 40 years, now. Only it’s had a new lease of life – just like the rider!”

Indeed so, for after finishing third in the 2005 Australian Historic Championship in Tasmania in his debut season on the born-again bike, resplendent in distinctive Gallic livery sporting a French tricouleur flag on each side of the fairing, Webster has been a consistent front-runner in the Period 5 class for the past two decades. In doing so, he’s brought more track honours to the Moto Martin marque than anyone else in the years since the French frame-maker was founded in 1972, because back then Georges Martin’s street-focused creations were only at best privateer grid fillers in Endurance racing, without any significant competition success to their name.

Aboard the Moto Martin Kawasaki the 63-year old Webster has frequently gone through the card at Aussie Historic events, winning all four races in the Forgotten Era class at both the 2012 and 2014 Island Classic meetings, and grabbing a lock on third place in the P5 Historic support races held alongside the Australian World Superbike and MotoGP rounds at Phillip Island, having finished on that step of the rostrum in six successive such races. Is that consistency, or what?!

Webster just so happened to find the Moto Martin Suzuki GSX1100 on eBay following a rule change that would allow him to run the bigger cube 16-valve 1100cc four-cylinder powerplant.

But faced with the 2011 Period 5 rule change that brought the cutoff year forward a year to 1982, thereby legalising the much more potent 16-valve Suzuki GSX1100 to take part, Webster was faced with joining the move upwards in performance, or else risk becoming a midfield runner due to the Moto Martin’s older, less potent 8-valve Kawasaki Z1R motor. With so few Martins imported back then by the firm’s Australian agent, Frenchman Bertrand Cadart’s Melbourne-based La Parisienne company, Scott’s loyalty to the French brand seemed set to be stifled – until eBay rode to the rescue with the February 2011 listing of a “Rare 1981 Moto Martin GSX1100 basket case, for sale at reasonable price”! Better still, it turned out to be located just 60km away from Pakenham, in North Melbourne.

“It was all dismantled, but very sound and had allegedly never been crashed,” says Scott. “The gentleman selling it had only a small terrace house, and was sick of tripping over it. I was first in with cash in hand, and took it away on the spot. I’ve used its frame, swingarm and a few engine parts, which gave me the basis to stay up at the front of the field on another bike painted in French colours!”

This turned out to be one of only two 16-valve Moto Martin Suzukis imported by Cadart, the very one which did exhibition laps at the Bathurst Australian GP meeting at Easter 1982.

Indeed so, and on a rare bike Down Under, since this turned out to be one of only two 16-valve Moto Martin Suzukis imported by Cadart, the very one which did exhibition laps at the Bathurst Australian GP meeting at Easter 1982. Three decades later it returned to the racetrack in its new owner’s hands, but this time to race in earnest rather than parade. The reborn roadbike-turned-racer made its shakedown debut in 2012, initially suffering some ignition problems, but by the following year Scott had it all dialled in, winning two support races at the Island Classic to place second overall in P5 Forgotten Era, repeating the result at the August Phillip Island National Challenge meeting as runner-up to Aussie Historic champion Michael Dibb on the six-cylinder T-Rex Honda.

But 2014 was the year the French-framed Suzuki came good, with Scott Webster winning the World Superbike Post-Classic support series aboard it with one race victory and two seconds, to push Rob Phillis into second place on a standard-framed Suzuki Katana, with Craig Ditchburn’s TZ750 Yamaha third. Same again at the August National Challenge, with Scott winning two races and finishing second to Mal Campbell in a third for the overall win, while each year he’s been selected for the Aussie team in the IC/ International Challenge, giving a good account of himself with a series of top ten finishes. Riding someone else’s bike in the 2016 Island Classic so as to save the Suzuki for the Forgotten Era races maybe wasn’t such a good idea, though, with Webster crashing unhurt on his own oil after the engine blew. But the old faithful Moto Martin Suzuki earned him three third places and third overall in Forgotten Era that weekend, behind Cam Donald’s McIntosh Suzuki and Marty Craggill’s TZ750.

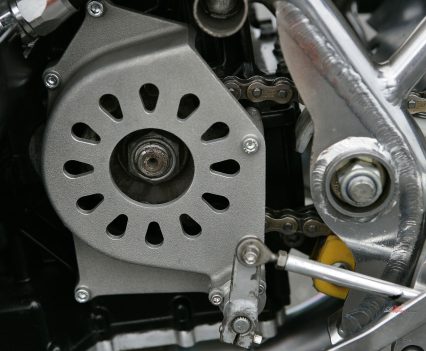

South Australian engine tuner Trevor Birrell, an Adelaide-based 11-times Pro-Stock drag racing champion, has taken the 16-valve Suzuki GSX engine out to the maximum possible 1198cc without re-sleeving it, by dint of using a later 2mm-bigger bore GSX1100EF cylinder block, then coaxing an extra 1mm from it to deliver 75 x 66mm dimensions with the aid of JE pistons running 11.2:1 compression, fitted to stock conrods mounted on a welded-up standard crank fitted with a US-made APE crank brace, and APE stud kit top and bottom. This crank has been machined to accept a straight-cut primary gear, while on the opposite end it’s has been modified to run a taper-mounted PVL self-energising CDI with twin adjustable advance curves, allowing Scott to dial up a new map via a laptop as needed.

The rev-limiter is set at 10,500rpm, with 144hp@9,500rpm from the air-cooled motor delivered to the rear wheel at.

The rev-limiter is set at 10,500rpm, with 144bhp peak power from the air-cooled motor delivered to the rear wheel at 9,500 rpm. The custom sump has been welded and gated to counter oil surge, but Trevor Birrell hasn’t gone too extreme in tuning the motor, given that some of his more extreme P5 motors churn out over 170bhp, but at the expense of reduced mileage. “I needed something that’s got to run a full season between rebuilds,” says Scott. “So Trevor builds the engine to last, as well as make good power. It’s a fair compromise.”

“I needed something that’s got to run a full season between rebuilds,” says Scott. “So Trevor builds the engine to last, as well as make good power. It’s a fair compromise.”

Inevitably, Birrell has focused most attention on the cylinder head, using a CAD design he’s developed himself to reshape the combustion chamber, then re-port and gas-flow the head. He’s fitted 1mm oversize stock Suzuki valves from the later EF Suzuki motor – meaning 31mm inlets and 26mm exhausts, and two of each per cylinder, of course – carrying Yoshimura springs and retainers. The twin overhead camshafts are also Yoshimura, operated by a Hy-Vo chain with a slipper-type camchain tensioner. Breathing is taken care of by four 33mm Keihin CR carbs, and a 4-1 Yoshimura titanium race pipe, with a titanium-wrap can. The all-Suzuki transmission comprises a stock GSX1100 five-speed gearbox matched to a slipper clutch sourced from a 2002-model GSX-R1000 with heavier springs, but standard plates – MA’s Post-Classic eligibility rules don’t mention slipper clutches!

This meaty motor has been rigidly mounted in the unmodified nickel-plated Moto Martin chrome-moly tubular steel perimeter spaceframe, which differs from Webster’s painted Martin Kawasaki chassis in that the open-cradle Suzuki frame’s tubes wrap round the outside of the cylinder head, rather than over the top of it as on the twin-loop Kwacker chassis. It carries a ‘90s-era 41mm Honda CBR600 fork fitted with modified internals via an Öhlins cartridge, set at a remarkably tight-for-back-then 24° head angle with just 97mm of trail thanks to the Manta Enterprises tripleclamps, and adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping. At the rear there’s a fabricated box-section chrome-moly steel swingarm running on needle roller bearings, with a fully-adjustable Öhlins monoshock with remote reservoir and cantilever operation – there’s zero linkage.

Webster has fitted 17-inch wheels to the Moto Martin to be able to use modern Dunlop slick tyres, as permitted by MA/Motorcycling Australia rule-makers to help hook up the considerable horsepower delivered thanks to the 1300cc top limit for Down Under Historic racing’s big bike category. This encourages tuners to go large on engine upgrades, thus adding to the show while also removing concerns about having to measure the overbored one litre-plus engines proliferating in the class.

As with its rivals, on the French-framed Suzuki this power is transmitted through a skinny 4.50in rear wheel, the widest allowed in Post-Classic racing, and to avoid likely confusion and for greater flexibility Scott uses all the same wheels and tyres on both his Moto Martins. The front one is a lightweight cast aluminium 3.50in Marvic normally shod with a 125/80 Dunlop KR106 slick, mounted with twin 310mm cast iron discs made locally for Webster by Manta Enterprises and gripped by twin-piston Brembo Serie d’Oro calipers, via braided lines and a Brembo master cylinder. At the rear is a much heavier 4.50in Katana wheel normally carrying a 165/55-17 Dunlop KR108, with a hefty cushdrive which Scott Webster favours to give the gearbox an easier time.

The chance to ride the Moto Martin Suzuki came at MA’s annual Broadford Bike Bonanza on the tight 2.16km track 60km north of Melbourne whose many slow turns and elevation changes posed quite a severe test for a big, fast bike more at home on flowing circuits like Phillip Island. And because of the nature of the BBB event which precluded the use of slick tyres, Scott had thoughtfully fitted a set of Pirelli Diablo street rubber – just the job. Best of all, I got the chance to compare and contrast the French-framed Suzuki with one of its greatest local rivals that I rode earlier the same day, Rex Wolfenden’s reigning Australian P5 Historic champion T-Rex Honda CB1100R, which uses a British-built Harris frame to harness an engine making identical horsepower to the Moto Martin Suzuki’s in a bike that is however a massive 22kg lighter than it.

The chance to ride the Moto Martin Suzuki came at MA’s annual Broadford Bike Bonanza on the tight 2.16km track.

Climb aboard the French-framed Suzuki, and the overriding impression you get when you first sit on the bike is how wide it is – as in M-A-S-S-I-V-E. That’s especially so compared to the seemingly smaller, svelter Honda I’d just been riding, which seemed almost dainty by comparison. Because of the fact it also acts as a shroud for the wide, wide frame rails which wrap around the hefty in-line four motor, the flanks of the broad but flat fuel tank are seemingly as wide as the clipon handlebars, even if they’re not, and seen from behind it’s evident that this is indeed a whole lot of motorcycle. Moreover, just as on Scott’s K-model Martin you’ll find this is a racebike that you nestle in rather than sit on, which in turn discourages hanging too far off the side, and coupled with the skinny rear tyre certainly makes you think hard before cranking it hard over to deck a knee.

Despite its seeming width the Moto Martin has huge ground clearance – you’ll be off the edge of the front tyre before anything touches down. I’m slightly taller than Scott, and found myself basically wedged in place aboard the plushly upholstered seat, making it hard to move around on the bike easily. Still, the broad 24-litre aluminium fuel tank was shaped so I could rest my chest on it down Broadford’s pair of straights, as I tucked well away behind the pretty effective full fairing’s wide tinted screen – the Moto Martin must indeed be a good bike for Phillip Island’s fast open stretches compared to its Naked-but-unashamed Katana rivals.

“Climb aboard the French-framed Suzuki, and the overriding impression you get when you first sit on the bike is how wide it is – as in M-A-S-S-I-V-E.”

Yet once you pick up speed, you discover that the Moto Martin’s apparent width and bulk is an optical illusion, which you’re honestly unaware of as you start to up the pace. Instead, especially by the standards of 1980 when the Martin frame was designed, this is a sweet-steering and comparatively agile motorcycle whose handling is precise and neutral both under braking and on turn-in.

“The Moto Martin has huge ground clearance – you’ll be off the edge of the front tyre before anything touches down.”

That broad screen is super-protective without affecting your ability to position the bike in a turn, which is sometimes the case with anything this wide – you don’t feel detached from the action on the Martin Suzuki. Thanks to the close-coupled and slightly cramped riding position that was exacerbated for me by the high-set footrests, I had to steer the bike without shifting my body weight around too much, but it still changed direction beautifully, while remaining stable under hard braking at the end of the straights.

“That broad screen is super-protective without affecting your ability to position the bike in a turn, which is sometimes the case with anything this wide – you don’t feel detached from the action on the Martin Suzuki.”

The brakes are just about OK, even if the cast iron front discs rather surprisingly don’t have a huge amount of bite – the smaller diameter similar brakes on my 750SS Ducati are quite a bit more responsive, even though both bikes have period stoppers with just two-piston calipers. The key ingredient here is weight – though you don’t much notice the Suzuki’s porky build in changing direction, it’s 25kg heavier than the Ducati, and that’s a lot. However, the 22kg lighter T-Rex Honda rather surprisingly didn’t stop any better, for the simple reason it has stainless steel discs. These don’t have as much bite as the Martin Suzuki’s cast iron ones, which moreover would excel in the rain. Several of Scott Webster’s best results have come in wet races – now I know why.

Scott’s also left quite a bit of engine braking dialled into the slipper clutch setup, which helps the Martin Suzuki’s brake package stop the bike from speed. So you must use the one-up left-foot race pattern gearshift to obtain assistance in stopping from the motor, taking care not to let the needle on the Scitsu tacho (the only instrument) dance beyond the 9,000-rev mark on the overrun. I used that as the mark for shifting up a gear, in which case you’ll find yourself right back in the fat part of the torque curve in the 6,500-7,500rpm zone – the 5-speed Suzuki road gearbox doesn’t have especially close ratios, but that doesn’t matter because of the amazingly broad spread of power and torque that Trevor Birrell has dialled into this engine. Given his drag racing background I will admit I was expecting a pretty peaky package with heaps of top end power – but I couldn’t have been more wrong.

For the Suzuki motor is muscular and torquey, and pulls like a tractor from low down, with 3,500rpm the threshold to serious acceleration that will have the front end aviating out of any second or third gear turn if you don’t have your right foot leaning on the rear brake lever. From there to the engine’s 8,500rpm power peak there’s a lovely, luscious, liquid spread of torque, which on a tight track like Broadford invites you to cut down on gearshifts and instead surf those waves of grunt to build engine speed smoothly and controllably from that 3,500rpm threshold on upwards, at a more than respectable speed for a 40-year old maxi-motor like this one, with an unlightened stock crankshaft.

“The Martin frame steers so well you can hit the same identical piece of tarmac lap after lap, using as much lean angle as you dare without asking too much of the front Pirelli.”

Once again, just as on his Martin Kawasaki, Scott Webster has set the carburation up absolutely perfectly, especially on part throttle, delivering an ideal pickup exiting any of the slow corners in the Broadford infield. The Suzuki engine’s throttle response is crisp and direct, clean and responsive without being snatchy. It’s so predictable you can start to get brave about how hard and how early to start asking questions of that skinny rear tyre, in transmitting the 144bhp on tap from the motor to the tarmac, allowing you squirt this big, heavy bike out of slow corners with relative impunity.

Yet the Martin frame steers so well you can hit the same identical piece of tarmac lap after lap, using as much lean angle as you dare without asking too much of the front Pirelli. The 41mm Showa CBR600 fork with the Öhlins valving gives adequate if not exceptional feedback from the front tyre, but Scott Webster has used his decades of Superbike experience to set the rear Öhlins monoshock up really well. This ironed out most of Broadford’s bumps, and especially delivered good drive out of the off-camber last turn on to the main straight, then again exiting the uphill right-hander leading on to the top straight – both times without pushing the front end in the kind of power understeer that was a common feature of big, powerful Japanese bikes back then. I know – I was there…

The Martin Suzuki holds a line well when you switch on the power to drive out of a turn, and part of that is down to the great rear suspension setup, which I must honestly admit surprised me by its effectiveness despite having no progressive rate link. We’re talking Öhlins here, though, so that’s obviously a factor – but another key issue is surely the completely linear surge of power from 3,500rpm upwards that Trevor Birrell has delivered in concocting this delightful engine. A great engine, packaged in a sweet-steering chassis. Vive la France!

1982 Moto Martin Suzuki GSX1100 Specification

ENGINE: Air-cooled dohc transverse in-line four-cylinder four-stroke with central chain camdrive and four valves per cylinder, 1198cc, 11.2:1 Compression Ratio, PVL self-generating CDI with 2 x adjustable advance curves, 4 x 33mm Keihin CR, 75 x 66m bore x stroke, 5-speed gearbox, Multiplate oil-bath Suzuki GSX-R1000 slipper clutch

CHASSIS: Twin-loop duplex cradle chrome-moly steel tubular perimeter spaceframe, Front: 41mm Showa telescopic fork with Öhlins cartridge internals adjustable for rebound damping and spring preload, Rear: Fabricated box-section chrome-moly steel swingarm with fully-adjustable Öhlins cantilever monoshock Front: 125/70-17 Pirelli Diablo on 3.50 in. Marvic cast aluminium wheel Rear: 130/60-17 Pirelli Diablo on 4.50 in. Suzuki cast aluminium wheel with cushdrive, Front: 2x 310mm Manta Enterprises cast-iron discs with two-piston Brembo Serie d’Oro calipers Rear: 1 x 240mm Suzuki disc with two-piston Brembo Serie d’Oro caliper

PERFORMANCE: 144hp@9,500rpm (at rear wheel), 182 kg with oil/no fuel, split 51/49, 268 km/h (Phillip Island 2014).

OWNER: Scott Webster, Pakenham, Victoria, Australia

1982 Moto Martin Suzuki GSX1100 Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.