Georges Martin is a genius when it comes to extracting performance out of a frame. Cathcart gives us the full history behind the bespoke frame brand Moto Martin...

French chassis constructor Georges Martin had the right idea at the right time, as well as the determination and dedication to put it into practice. Moto Martin hand-crafted bespoke frames to house some of the best Japanese powerhouses of the ’70s and ’80s…

Georges Martin had the right idea at the right time, as well as the determination and dedication to put it into practice.

That’s how a total of 5,800 complete hand-crafted Moto Martin café racers and frame kits were built between 1972 and 1986, almost all of them focused on harnessing the significant performance of the new generation of four-cylinder Japanese ultrabikes in a way that the heavy, slow-steering, often flimsy and unstable original chassis were unable to do.

Check out our racer test on the Moto Martin Suzuki GSX1100 here...

But, inevitably, the Japanese manufacturers eventually acquired their own expertise in the black art of frame design, and the arrival of the Suzuki GSX-R750 in 1985 with its race-quality aluminium chassis, marked the end of the golden era of specialist frame builders in Europe for companies like Rickman, Dresda, Egli, Segale, P&M – and Moto Martin. Only Britain’s Harris Performance and Spondon, as well as Holland’s Bakker Framegebouw survived, by focusing on Grand Prix and other competition chassis designs, plus superior swingarms and the like for the new generation of Superbikes.

A total of 5,800 complete hand-crafted Moto Martin café racers and frame kits were built between 1972 and 1986, almost all of them focused on harnessing the significant performance of four-cylinder Japanese ultrabikes.

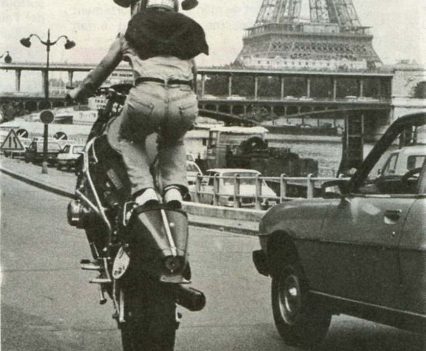

Born in Nantes, in the Vendée region of western France, Georges Martin moved to Paris to study at engineering school, then found work there as a draughtsman for an elevator company. A dedicated biker, he rode a Velocette Thruxton which in 1969 he swapped for one of the newly launched CB750 Honda fours, but while this delivered an entirely different level of engine performance to the British singles he’d ridden until then, Martin reckoned its handling left a lot to be desired. Realising this was a common complaint among Honda’s lengthening list of customers, Georges gave up his job and moved into a small workshop near the Bastille, where he worked on building a new chassis for the Honda engine by day, and slept there by night.

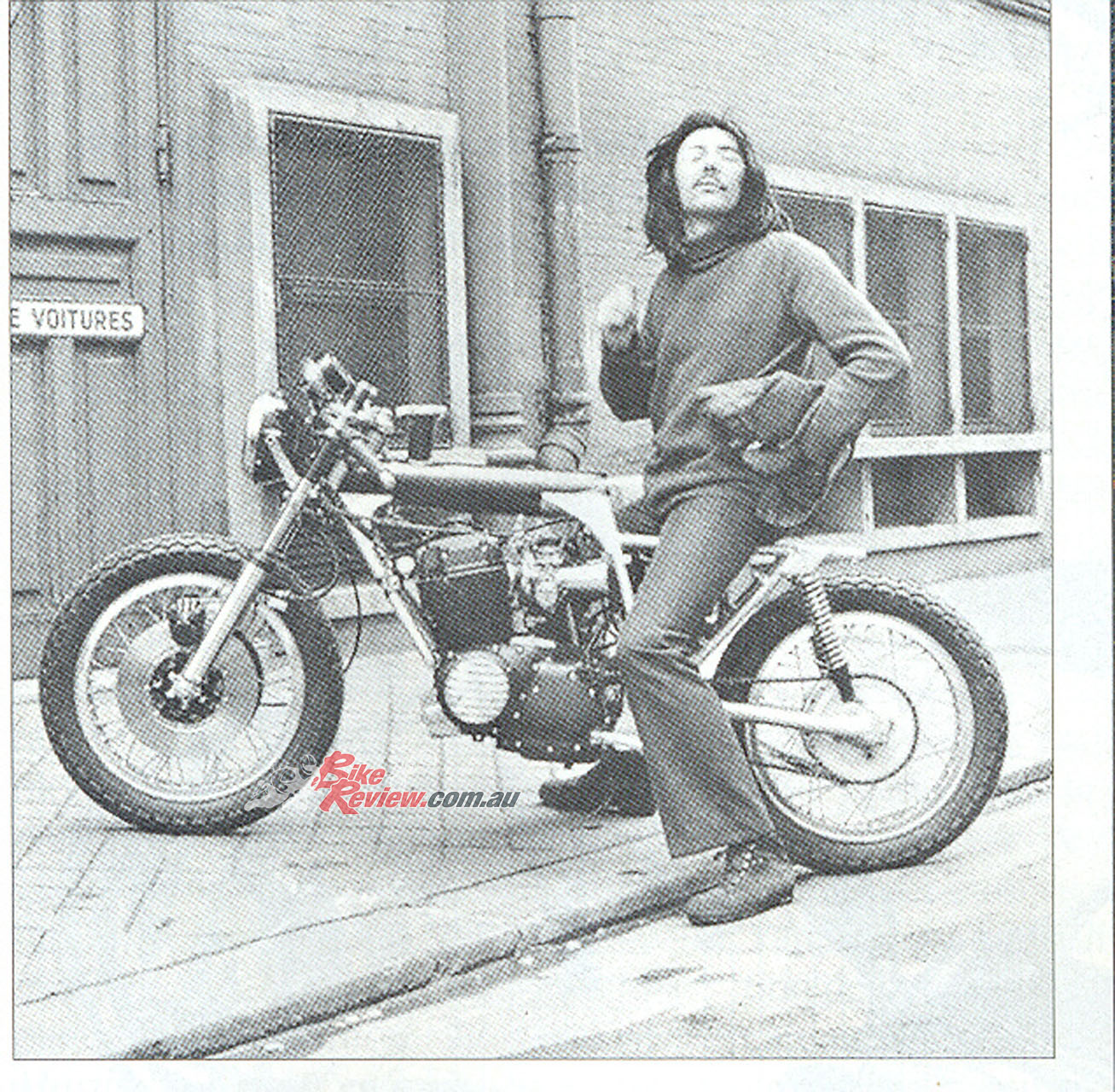

Georges Martin with the original Honda powered Moto Martin. His twin-shock design in 25 CD 4S chrome-moly steel, offered with racing-style full fairing bodywork, was closely based on the recently announced Egli-Honda spine.

His twin-shock design in 25 CD 4S chrome-moly steel, offered with racing-style full fairing bodywork, was closely based on the recently announced Egli-Honda spine frame design which would duly win the 1972 FIM Endurance Championship ridden by Georges Godier/Alain Genoud. This used the central tubular backbone as an oil tank for the dry sump Honda motor, and when he displayed it in February 1972 at France’s annual Salon de Compétition staged less than a kilometre from his workshop, offering replicas of his so-called Bol d’Or design at a much lower price than the costly Swiss frame kit, Martin was inundated with orders.

Martin reckoned the CB750’s handling left a lot to be desired. Realising this was a common complaint, Georges gave up his job and moved into a small workshop near the Bastille…

This commercial success, which intensified once he delivered bikes to customers that completely lived up to expectations in delivering improved handling, plus a weight saving of around 40kg compared to the standard 210kg Honda, necessitated moving to a bigger workshop, so in 1973 Georges Martin established a Moto Martin factory in the French seaside town of Les Sables-d’Olonne, near Nantes, where he also opened a Kawasaki dealership. Good timing, since the legendary 900cc Z1 had just been launched, endowed with even more engine performance than the 750cc Honda, but suffering in consequence from even worse handling problems. So the Moto Martin chassis range was expanded with kits for this engine, too, as well as the H2R two-stroke triple and its Suzuki GT750 counterpart.

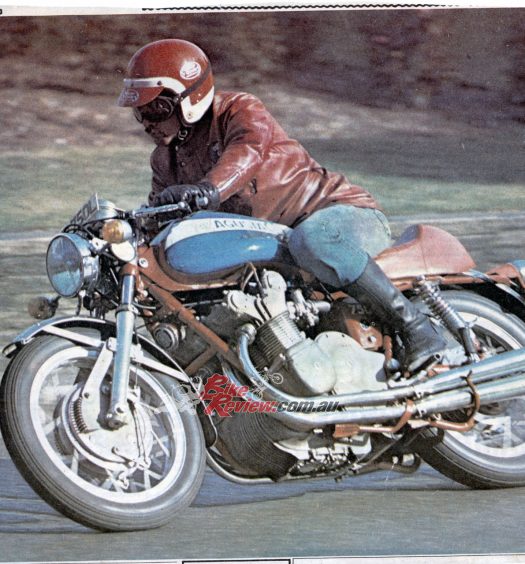

But the more substantial architecture of the wet sump Kawasaki Z1 motor meant that it wasn’t suited to his Honda spine frame format, so alongside this in 1974 Martin introduced a new open-cradle spaceframe design with cantilever monoshock rear end, once again in chrome-moly steel. This became the trademark Moto Martin chassis layout for the next decade, housing initially only the Kawasaki Z900 and later Z1000 motors, but in time adapted to a wide variety of other engines.

Fitted with Martin’s own design of fork and cast aluminium wheels made for him by Betor and JPX respectively, this maze of relatively small-diameter thinwall tubing was invariably nickel-plated, and surmounted by a distinctive café racer body kit complete with a spoiler incorporated in the seat, which became a Moto Martin trademark. Despite the well-upholstered nature of the monoplace single-seat, and the fact that his bikes never really excelled in competition – despite allowing a good number of privateers to indulge in the growing French passion for Endurance racing – Martin designed his kitbikes very much in the spirit of racers with lights, as Georges Martin himself explained in an interview published in 1979.

“Our customers are looking for a certain kind of technical design which isn’t necessarily the most effective format, but is certainly the most original, and striking,” he said. “Moto Martin doesn’t claim to construct the best bikes in the world. So the open spaceframe design we make for Kawasakis and Suzukis is better than the originals, but is less stiff a structure than our Bol d’Or chassis for the Honda, which uses the engine as a full load-bearing structure – but our customers prefer our spaceframe design to this one, because they think it looks better. This means we must always pay careful attention to the technical solutions we employ in our designs, taking care to evaluate each component on the basis of three different criteria.”

“It must give the impression of coming from the racetrack, since that’s what our customers want”…

“One, it must give the impression of coming from the racetrack, since that’s what our customers want; two, it must be simple to manufacture, because that in turn guarantees reliability; and three, you must always keep the price to the customer in the back of your mind, because whatever we produce must be affordable. I know myself what it means to be a biker, and to have to count your pennies to go riding. If you don’t pay attention to costs you’ll lose the customer – the dream we’re selling must be within people’s reach.”

“Our customers are looking for a certain kind of technical design which isn’t necessarily the most effective format, but is certainly the most original, and striking,” said Georges Martin…

Moto Martins were thus always favourably priced, especially compared to Bimota, another specialist manufacturer with a comparable range. But that philosophy worked just fine, and indeed by 1979 Moto Martin production had continued to expand to the point that space was once again an issue. In autumn that year, the company moved into a new 1,000m factory in Les Sables d’Olonne, permitting the workforce to increase to 24 in 1980, rising to 35 by 1983, together responsible for producing more than 600 complete bikes and frame kits per year – half of them going to French customers, one-third to Germany, and the rest mainly to Switzerland, Belgium, the USA and Australia. Frames were now being built to house the Kawasaki Z1000J, Honda CB900FZ, Suzuki GS1000 and Yamaha XS1100 motors – the latter after conversion to chain final drive – and the Honda version of the chassis now featured a twin-loop format, rather than the open cradle of the other designs.

Moto Martins were thus always favourably priced, especially compared to Bimota, another frame specialist.

But it was a fanciful tale that this was done after it was discovered that the crankshaft would break on the CB900FZ motor, unless it was fully supported in a closed frame structure, rather than an open cradle one. Reality was more prosaic, according to Georges Martin, who insists today that this story is pure fiction. “It has nothing true about it – this never happened with our frames,” he insists. “Our Martin frame designs derived from both marketing and race related considerations. The spine frame (cadre poutre) is very easy to build, and it’s rigid and light, but the cylinder head is difficult to access. The open cradle space frame (cadre périmetrique) is good looking but heavy, and easily damaged in case of a crash. The twin-loop frame (cadre fermé) was firstly designed for the race track, just as other frame manufacturers did at this time, because it turned out to be the best design in terms of handling stability and engine accessibility. Full stop.”

In 1980 the first examples were delivered of the most iconic of all the various Moto Martin models, the CBX Six. Uniflex rear suspension with a progressive-rate link was now available, and the use of Brembo Serie d’Oro brakes, Marvic wheels and Marzocchi forks became standardized, with the rear monoshock invariably a French-made DeCarbon. In 1983 a shorter-wheelbase version of the spaceframe was offered, with a 50mm shorter 1450mm wheelbase and sharper handling thanks to a steeper 25º head angle, plus tighter steering geometry via a reduced 105mm of trail – Moto Martin had its own tripleclamps cast to achieve this.

With production peaking of his existing designs, Georges Martin could now occasionally explore building frames for other, non-Japanese engine suppliers, including Laverda twins and triples, as well as a Triumph-3 design which was closely derived from the existing Rob North chassis, and even a prototype 125cc Villa for a projected monomarca championship, which sadly never happened. Moto Martin frames were also built to house a Ducati 860cc V-twin motor, a Benelli Sei – obviously based on the CBX design! – and even a BMW K100 engine. But the Japanese fours still made up the vast majority of Moto Martin frame kits, including by 1983 the Suzuki GSX1100 and Honda CB1100R – which made the appearance at the end of 1983 of the Honda VF1000, complete with square-section frame tubing, albeit steel, followed a year later by the aluminium-chassised Suzuki GSX-R750, which proved such a game-changer.

Martin learned how to extract the most performance out of a frame and paired it with some of the best Japanese motors.

The Japanese manufacturers had finally learnt how to build a light, good-handling chassis, and with the economies of scale made possible by their volume, at a much lower price than the likes of Georges Martin could hope to compete against. With sales plummeting, in 1986 Martin switched completely to four wheels, terminating Moto Martin’s status as a bike manufacturer in favour of creating French-made copies of the Lotus Seven, later joined by surprisingly accurate recreations of the AC Cobra and Ford GT40, powered by American V8 motors.

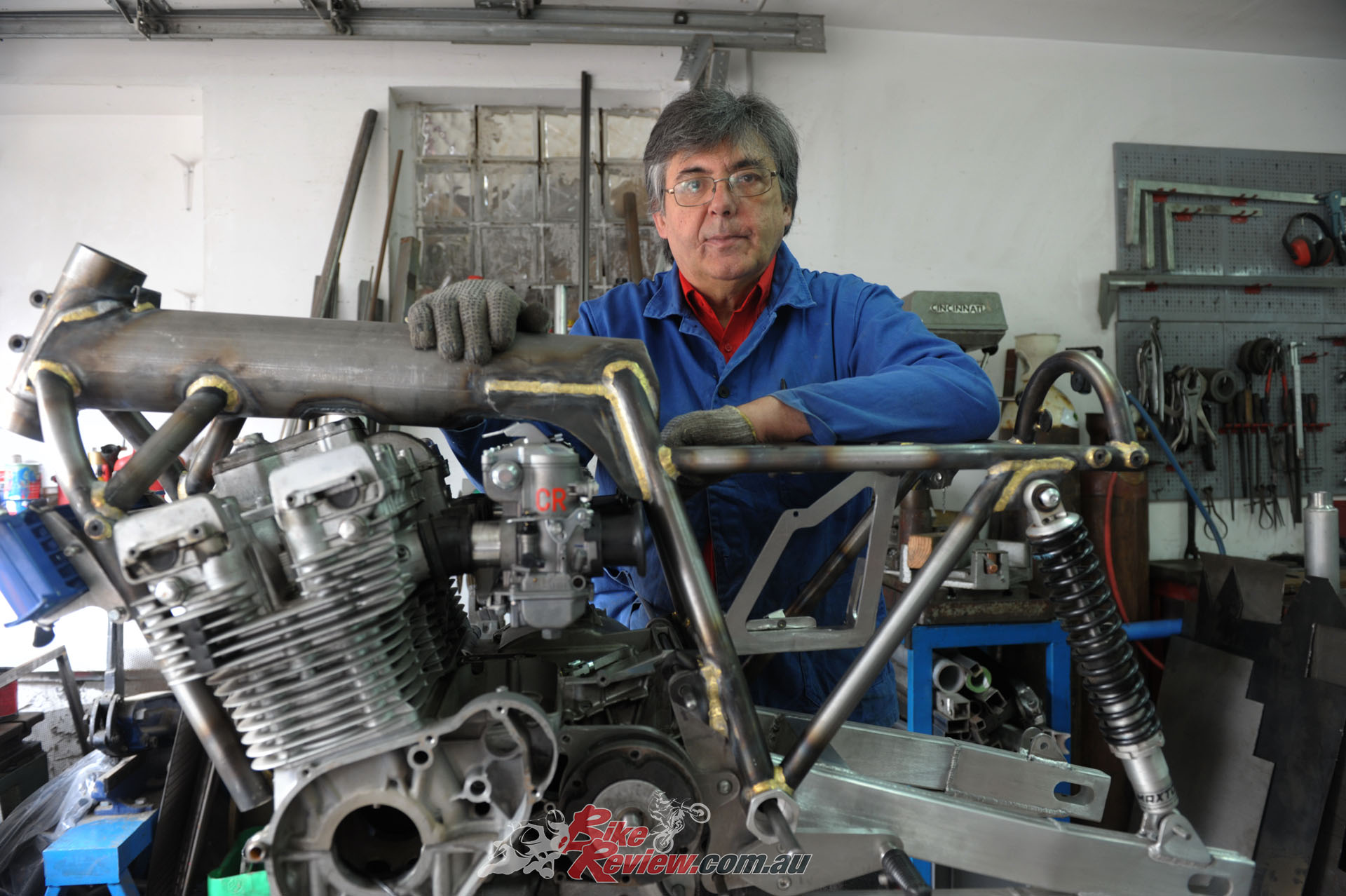

35 years on, in his retirement years Georges Martin has since returned to the motorcycle world by establishing GMP/Georges Martin Production www.martin-caferacer.com to provide spare parts for all Moto Martin models, as well as a range of retro accessories. He’s also created the Moto Martin Club www.motomartin.com for owners of the bikes he had a hand in making personally, and has also picked up the welding torch again in order to make a handful of new examples of his traditional designs for Classic Endurance racing, powered by the RSC1000 Honda and Kawasaki Z1000 motors. The wheel has turned full circle, and Moto Martin production has resumed….!

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.