Harald Bartol started young, aged 19 when he built the 50cc Puch special he began racing with in 1966, finishing second in his first-ever race before gradually carving a reputation for himself by using his skills to tune the bikes he raced with some distinction... Words: Alan Cathcart Pics: Kel Edge

For 1972 Harald Bartol acquired the ex-works Suzuki RZ64 twin on which Germany’s Dieter Braun had won the 1970 125cc World title, and Barry Sheene had finished a close runner-up in the 1971 World series to Angel Nieto’s Derbi…

Check out our feature on the Bartol 250cc GP Racer here…

With Suzuki long retired from 125GP racing, Bartol had to make all the spares needed to run the bike himself, and tune it too – to such good effect that he finished seventh in the 1972 125GP World Championship on the Japanese bike, including scoring his first GP rostrum finish with third place on the demanding Opatija circuit.

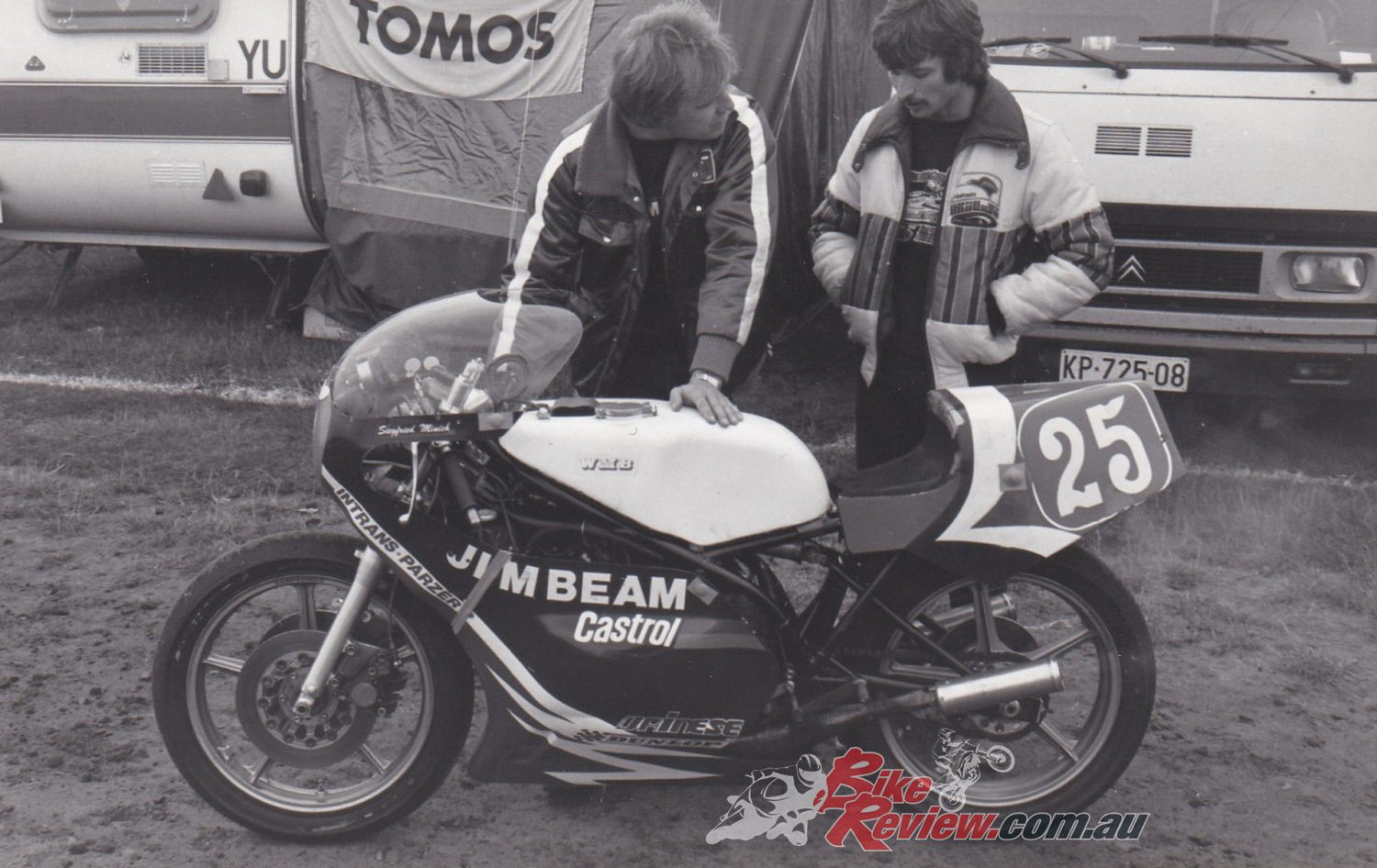

This heralded Harald Bartol’s rise to prominence in 125GP racing, tuning the bikes he rode to a succession of 13 rostrum finishes over the years, before retiring from racing in 1980. This included a total of five second places and eight thirds – but never a GP victory, although Harald won fourteen Austrian championships as a rider between 1970-80 in the 50/125/250cc classes. His 1.80m/5’10” stature and extra weight told against him in a class like 125GP, where a 1.64m/5’4” ‘star midget’ like Angel Nieto was increasingly the norm. Harald’s best season came in 1978, when he finished fourth in the 125GP points table aboard his self-tuned privateer Morbidelli, just two points behind third-placed ex-champion Pierpaolo Bianchi on the factory Minarelli. But though Harald finished a solid eighth in the title series the following year, he was now focusing on preparing bikes for other riders, and on using his accumulated experience and technical skills to build his own Bartol GP racers. So he retired from racing in 1980, to sink DM 100,000 of his savings accrued during a 15-year riding career into developing the Bartol rotary-valve parallel-twin GP racers for the 250cc and 350cc classes, which first appeared in 1981. Ultimately, too few customers opted to take advantage of the extra performance offered by the Austrian motors, and together with the post-1982 demise of the 350cc class which removed many potential clients, and the growth to prominence of that other Austrian 250cc motor, the rotary-valve tandem-twin 250 Rotax which powered so many different bikes in the 1980s, the Bartol GP project died a death at the end of 1983. “I just didn’t have the resources, either financial or structural, to continue as a manufacturer,” says Harald. “But we had fun trying – even I ended up with empty pockets!”

But before that Bartol’s debut gig as a freelance race engineer had seen him play a walk-on role in an event of some significance for the future direction of GP racing, when in March 1980 he was commissioned to source and prepare an RG500 Suzuki for a 19-year old American kid from Louisiana to race outside the USA for the first time, in the US team for the annual Transatlantic Challenge Match races in the UK. That kid’s name was Freddie Spencer, and this was also the first time he’d ever raced a 500GP bike of any kind – yet within ten laps of the Brands Hatch short circuit on the Bartol-tuned RG500, he’d broken the lap record on a bike he’d only seen for the first time that morning! Defeating World champions Kenny Roberts and local hero Barry Sheene to win both races held that day (one might have been fluky, but not two!) on the Bartol-prepared customer Suzuki underlined the young American’s talents – and Harald Bartol’s stock as a tuner.

The demise of the Bartol 250/350GP twins project left Harald Bartol free to focus on helping World champions like Ricardo Tormo, Stefan Dörflinger, and sidecar ace Rolf Biland gain their titles with engines he’d tuned for them, alongside many other customers from all round Europe. But Harald’s closest relationship was with fellow-Austrian August ‘Gustl’ Auinger, whose Monnet-sponsored machine which Gustl took to three GP victories and third place in the 1985 125cc World Championship, was a customer MBA twin completely re-engineered by Bartol to have the beating of the works Garellis then dominating the points table. Indeed, by 1986, the Monnet had been registered with the FIM as a Bartol, so Auinger’s GP victories at Silverstone and Misano that year remain the first and only official Grand Prix wins for the Bartol marque, en route to Gustl’s fourth place in the championship – the highest finish for a bike bearing the Bartol badge.

Harald’s tuning skills had earned the respect of many key players in the GP paddock, not least Kenny Roberts, who as Yamaha’s front man in GP racing, introduced Bartol to the Japanese firm. This led Harald to undertake significant R&D on Yamaha’s 250GP and 500GP factory motors, which peaked in the 1990 season, when he tuned the works YZR250 V-twin motor which took John Kocinski to the 250cc World Championship – the design was in fact essentially his own, which explains why it differed so radically from later customer TZ250 V-twins. Bartol then spent two seasons in 1990-91 as chief engineer for the Ducados Yamaha satellite team, looking after the V4 YZR500 which Juan Garriga took to sixth and seventh places in the World Championship those two years, and the TZ250M ridden by today’s Honda MotoGP team manager, Alberto Puig.

In 1992-93 Harald Bartol served his first stint as race engineer for Gilera, when he was recruited by the Italian marque’s chief engineer Federico Martini to supervise development of its 75º V-twin crankcase reed¬-valve 250GP contender. Brought in too late to influence design of the engine, Bartol had to make the best of what he was given to work with, and the results were disappointing, forcing Piaggio management to pull the plug on the Gilera GP effort at the end of ‘93. But after a period prepping engines for many GP privateers, in 1998 Harald was hired by Derbi to create a 125cc contender to power the Spanish firm’s GP comeback. Harald just happened to have a single-cylinder crankcase reed-valve engine design in his pocket, one he’d earlier made for Yamaha to power a new TZ125 that was eventually stillborn. This motor fast-forwarded development of the Derbi, which took to the track in 1999 in the hands of Youichi Ui and Pablo Nieto. Aside from the chassis built in Britain by Fabrication Techniques to Bartol’s specifications, the bikes were entirely created in Austria in Harald’s workshop in his home village of Strasswalchen, 20km from the KTM factory. After a troubled debut season the Bartol-built Derbis came good in 2000, with Ui winning five GPs to stay in contention for the World till the penultimate race at Motegi, when he crashed out of second place to hand the title to Aprilia’s Roberto Locatelli – ironically, later to ride for Bartol aboard the KTM road racer in 2003.

In 2001 it finally came good for the project, and Harald Bartol could derive well-earned satisfaction from seeing Manuel Poggiali take the bike he’d created – now rebadged as a Gilera, after Piaggio’s purchase of Derbi – to the 125GP World Championship, ahead of Youichi Ui on the identical Derbi, in second place. This 1-2 title sweep demonstrated Harald’s proven skills and tuning talents, so KTM boss Stefan Pierer didn’t have to look too far to sign up a man with proven technical expertise to spearhead the road racing challenge of the Austrian kings of the off-road world when he decided to enter 125GP in 2003, appointing Bartol as Technical Director for the KTM Grand Prix Road Racing Team.

To create the crankcase reed-valve KTM FRR125 with its highly efficient central ram-air intake, Bartol started with a clean sheet of paper, using as a basis his four years of acquired knowledge from developing the title-winning Gerbi/Dilera. A low-key debut in 2003 saw KTM achieve its first podium finish courtesy of Finland’s Mika Kallio, but in 2004 it was his Aussie teammate Casey Stoner who scored KTM’s first victory with Bartol’s baby, in Malaysia. Kallio and his new Hungarian teammate Gabor Talmacsi took seven more wins between them in 2005, en route to second and third respectively in the World Championship. Kallio again finished second in the 2006 title chase, with three more race wins – but meanwhile the first Bartol-designed 250GP racer since the bike that bore his name a quarter-century ago, had taken to the tracks in KTM colours midway through 2005, with another Aussie rider, Anthony West, coming within one second of scoring a dream debut victory for the bike in a soaking wet British GP at Donington. Second in its first race showed the new bike had potential – a fact underlined by West’s replacement Hiroshi Aoyama’s pair of dry weather victories in 2006, en route to fourth place in the World Championship, with two more each in 2007 for Aoyama and Kallio. In 2008 Kallio finished third in the points table with three more victories – the same year that a certain Marc Márquez joined KTM to race the FRR125 to a single podium finish in his debut season. At the end of that year the 250GP class was killed off by the FIM in favour of Moto2, a control-engine class using streetbike motors, and though KTM’s 125GP team continued for another year, with Márquez finishing eighth, at the end of that’s season KTM pulled out of MotoGP competition, and with it, Harald Bartol’s 40-year stint in GP race paddocks came to an end.

Charming but straight-talking and never afraid to speak the truth, Harald Bartol, now 72, is still developing engines, still experimenting, still learning – and still having fun. Never afraid to call a spade a spade – declaring that “The 250GP two-strokes were the racehorses of the GP paddock, but the Moto2 bikes are the donkeys!” was hardly likely to endear him to Dorna, even if the comment brought massive support on social media – Harald has a surprising candidate if you ask him to nominate the most fascinating engine he’s worked with over the past half-century of fruitful experimentation. “The US Army contacted me in the 1980s to help resolve some problems they were having with the two-stroke motors powering their Cruise missiles,” he says. “They were turbocharged two-litre V6 diesels each delivering more than 1,000 bhp – just fascinating pieces of engineering. But I’m not allowed to talk about them, so if I tell you any more, I’ll have to kill you!”