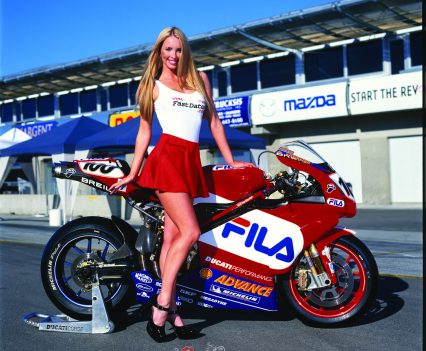

Ducati are currently dominating WorldSBK and MotoGP, we take a look back at their last glimmers of success before a dry spell. AC tests out the 2003 Hodgson Ducati 999 F03! Photos: Kel Edge.

Ducati’s reassertion of its WorldSBK supremacy in 2022-23, with double title wins for Bautista after the Italian factory went a decade without any championship success, prompts a look in the rear view mirror at Superbike racing’s history with the Ducati 999…

Ducati’s reassertion of its WorldSBK supremacy in 2022-23 after the Italian factory went a full decade without any championship success, prompts a look in the rear view mirror at Superbike racing’s history with the 999 Hogson Racer…

For exactly 20 years ago in 2003, the desmo mob were smarting from Honda wresting the coveted World title back from them, courtesy of Colin Edwards and the SP-02 V-twin not-a-Ducati – whereupon the Japanese giant promptly retired from the scene to focus on retaining its MotoGP World title, which it had earnt in the new category’s debut season with its V5 RC211V missile.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

This left Ducati as the only factory team on the World Superbike grid, with returnee Neil Hodgson (replacing Troy Bayliss, who’d moved to MotoGP) and Ruben Xaus mounted on the first race versions of the radically redesigned but controversial looking 999 streetbike created by Pierre Terblanche. This had been launched at the September 1992 Intermot Show in Germany, and was by then in pursuit of showroom success all around the world, having replaced the ultimate 998 evolution of the iconic Massimo Tamburini-designed 916 in dealer showrooms around the world. But at that stage for the 2003 season, only the two factory bikes had adopted this platform for WSBK racing.

Don’t underestimate the extent of the challenge that faced Ducati in 2003. It was one thing to replace a motorcycling design icon and two-wheeled talisman that had earned them a total of six WorldSBK titles, supplanting it with an all-new freshly-styled streetbike that was better geared to taller riders from Northern latitudes who were collectively their main customers – but quite another to retain that winning streak with the new bike on the racetrack, in its first year of competition. Yet that’s what the Ducati Corse Superbike race team did with the F03 race version of the 999 street bike.

The extent of Ducati’s achievement in winning all but two of that season’s 24 races with the new face in Superbikes was masked by the fact that they’d effectively been racing against themselves.

However, the extent of Ducati’s achievement in winning all but two of that season’s 24 races with the new face in Superbikes (with privateers James Toseland and Frankie Chili winning those other two on 998s, for a Ducati clean sweep of the entire season’s races, the first and only time that has ever happened for a single manufacturer) was masked by the fact that they’d effectively been racing against themselves. With the exception of Gregorio Lavilla’s solitary Corona Suzuki wearing intake restrictors in a transitional season when Ducatis didn’t have to, the two Fila-sponsored 999 F03 factory racers had only had to contend on a regular basis with beating their one- or two-year old 998 desmo V-twin.

Nobody was more disappointed at Honda’s decision to pull out of World Superbike for 2003 than Ducati, thus denied the chance to gain revenge for losing the World title to the Japanese marque in 2002, in that thrilling last-round shootout at Imola. Yet, as it turned out, Honda perhaps inadvertently did Ducati a good turn, and themselves a disfavour, by allowing the Italian factory’s Ducati Corse race shop to ease back on developing the all-new Superbike, in favour of getting their new V4 Desmosedici GP3 MotoGP contender up to speed in double-quick time in its debut season, which it duly did by leading its first race before beating Honda’s previously dominant RC211V to the chequered flag in just its sixth start. Take that, Honda!

The chance to ride Hodgson’s 999 F03 midway through the season at Misano, the day after Neil’s debut race crash that year had left teammate Xaus to double-up on race wins, answered the inevitable questions about whether all the Lancashire lad had to do was to turn up and stay on, to win the title. After twenty laps in 32°C temperatures, I reckoned Neil deserved a better shake than he’d been getting for his race-winning achievements that season, after winning the first nine races in succession.

Check out our interview with Neil Hodgson here…

That’s because with so little testing, this was very far from being an easy bike to ride at the sort of speeds you needed to in order to beat the likes of James Toseland, Frankie Chili, Regis Laconi and Chris Walker on well-proven, well-sorted examples of the previous generation of V-twin desmo hardware – let alone the consistently improving next generation of one-litre Superbikes, represented by Gregorio Lavilla’s Corona Suzuki GSX-R1000, which I happened by chance to be testing that same day, on the same track, as the Fila Ducati 999.

Though its sense of refinement and racetrack presence was such that you could be forgiven for thinking that it was a product of the MotoGP school, rather than a racer emanating from a street-legal motorcycle, the F03 was indeed directly derived from the Terblanche-designed 999 streetbike. This had not only caused great controversy amongst Ducatisti because of its innovative looks, it also represented the first time in a decade that taller riders had been able to feel comfortable on a Ducati sportbike, because of its South African designer’s clean-sheet approach to desmoquattro architecture.

Yet while the 999 F03 was not only the first Ducati Superbike in a decade of track-testing each iteration of the desmo V-twin school of Superbike design, with a riding position that I personally fitted and felt comfortable sitting in, rather than on, it was also the one aboard which I had to work hardest physically to ride at any sort of pace.

“This was a very demanding bike to lap fast on, you must constantly be moving yourself about back and forth.”

This was a very demanding bike to lap fast on, one where you must constantly be moving yourself about back and forth in the seat, as well as side to side, as usual. Woe betide you if you didn’t position your body weight correctly at any given moment on the racetrack, because the 999 F03 would tell you for sure that you screwed up, and slap your face for doing so, telling you to wake up and pay attention, stupid – or else! It was very definitely not an easy bike to get the best of, especially compared to its well-sorted 998 predecessor, where you were more wedged in place on top of the bike with a higher-set seating position plus a taller rear ride height, all combining to force more of your body weight onto your arms and thus the front wheel.

“The 999 F03 would tell you for sure that you screwed up, and slap your face for doing so, telling you to wake up and pay attention, stupid – or else!”

On the 999, by contrast, you were sitting noticeably lower in a more spacious seat, which did however offer the luxury of tucking yourself away behind the smoothly-raked screen in a way I’d never been able to do on a desmoquattro Superbike since 1993, and the last of the old 888s. That already makes the bike faster in a straight line for a taller rider than the old 998, even before the improvements to the F03’s engine package wrought by Ducati Corse engineers. But in Neil Hodgson’s case it also meant he could take full advantage of his 125GP-derived riding technique, where he moulded himself to the fuel tank/airbox cover and even flattened his elbows along its flanks.

“It was very definitely not an easy bike to get the best of, especially compared to its well-sorted 998 predecessor.”

Not a lot taller than Neil, I could make a passable imitation of doing that down Misano’s two straights, just as I remember being surprised I could do when I first rode the prototype 999 streetbike at Monza six months before its launch – but beware doing so, because the 999 had some tricks up its sleeve ready to play on you if you got too pleased with yourself. After riding it, I wouldn’t have called this a nervous-handling bike, as some pundits had done without ever sitting on it, because it rode bumps well and steered brilliantly. It was more a bike that just required even greater thought and care in riding it than usual on a finely-honed factory racer – let alone an extra degree of physical input from the rider.

I realised this on my first flying lap at Misano, after braking hard for the first left hander where the day before Neil had fallen off in the lead of Race One. The 999 stopped brilliantly – and not just because of the great bite yet good feel from the Brembo radial brake package, which in Neil’s case entailed smaller 305mm front discs, the largest diameter ventilated rotors Brembo then offered, thus combating brake fade or distortion due to overheating.

Because the seat was so spacious on the F03, you had to work hard at positioning yourself within the bike.

But two additional key factors were the Ducati’s great slipper clutch, which you could feed out progressively to really maximise engine braking without chattering the back wheel under reverse torque, even with those big pistons, and the lower seating position, which in turn reduced weight transfer under braking. This meant you could stop the Ducati very hard and late, but with lots of stability that allowed you to pick a line and stick to that – it didn’t move around as much as the older bike, unless like Ruben Xaus you used a lot of back brake in slowing down.

However, because the seat was so spacious on the F03, you had to work hard at positioning yourself within the bike – nominally, the rider sat 25mm further forward than on the 998, but you had what felt like more than twice this amount to play with back and forth, despite the thick rear pad Neil had mounted on the seat. You needed to let yourself slide forward on the seat under heavy braking, to load up the front wheel with your body weight for extra grip in the turn, because with less weight transfer owing to the lower, more aerodynamic riding position, you must deliberately compensate for that physically while slowing for the bend with the aid of the front brakes and the slipper clutch – like Neil, I didn’t use the back brake to stop the bike.

You needed to let yourself slide forward on the seat under heavy braking, to load up the front wheel with your body weight for extra grip in the turn. Like Neil, I didn’t use the back brake to stop the bike.

I couldn’t complain about the front suspension settings on the 999’s 43mm Öhlins fork, which allowed me to keep up what seemed like pretty respectable turn speed, even trail-braking on the angle into the apex. But then, mid-turn, you had to gauge the right moment to push yourself back in the seat via the clipons and mainly the outer footrest, to load up the back wheel with your body weight, for extra traction under acceleration. The Ducati steered OK in the turn, but it was important to pull it upright as early as possible for the exit, to use the fat part of the rear Michelin for maximum traction, because otherwise you risked getting a slide if you threw all that fabulous V-twin engine’s grunty torque at the side of the tyre out of the apex – especially a standard 16.5in rear, such as Michelin gave me for my test: maybe Neil’s tricker rear tyre might have better side grip than the one I used did?

Now you’re accelerating, driving hard out of the turn under the waves of usable torque that had always been Ducati’s trump card – but watch out, because there was a fine balance between having your body weight moved backwards in the seat for extra traction, and standing on the footrests to keep the front wheel on the ground, which you obviously couldn’t do with the bike cranked on its side. After a couple of leaned-over power-wheelies and subsequent crossed-up landings led to fits of the shakes – me and the bike, both! – and subsequent tank-slappers exiting the slow Misano chicane opposite the pits in bottom gear, I realised I needed to touch the back brake on the exit, to keep the front wheel down.

Fine, but don’t then get all pleased with yourself and forget to push yourself forward again in the seat going down the next straight, else sure as red stands for Italy you’d get the Ducati dancing from side to side, in what seemed like a determined attempt to flip you off the back! When that happened, it was absolutely impossible to wrestle it into submission and stop the front wheel flapping by standing on the footrests and pushing your chin over the steering head, without also easing off the throttle and losing momentum – and a stronger, fitter man than me named Neil Hodgson confirmed this to be the case.

Tank-slapping down the straights had another downside, beyond the obvious one that you couldn’t go as fast as you wanted, and risked getting chucked off if you didn’t back off the throttle to recover!

So, the trick was to stop that happening in the first place, and that meant using the footrests and ‘bars to force yourself forward on the seat again under acceleration, then gradually slide back again under the screen down a longer straight as speeds mounted, for maximum streamlining, while taking care not to unweight the front end unduly as you did so, else you’d get the front wheel flapping and would have to back off the gas to recover. Phew! Reckon I was perspiring more from mental stimulus than physical effort in those oven-like conditions, after my 20 laps sitting the term exam for Ducati 1.0 at the University of Misano.

Reckon I was perspiring more from mental stimulus than physical effort in those oven-like conditions, after my 20 laps sitting the term exam for Ducati 1.0 at the University of Misano.

Tank-slapping down the straights had another downside, beyond the obvious one that you couldn’t go as fast as you wanted, and risked getting chucked off if you didn’t back off the throttle to recover! After 6-7 laps of my first session, before I learnt how to counter the instability at birth, I had the feeling the front tyre had gone off – it felt squirmy and greasy in the centre of the tread when I came to brake hard at the end of the back straight. Side grip fortunately seemed OK – but still, something felt wrong. “Yes, Neil had the same thing happen at Monza,” said Ducati team manager Davide Tardozzi, when I stopped to tell him about it. “You think the tyre’s gone off, but in reality it’s the instability down the straight which has overheated the centre of the tyre. Just another thing to contend with!”

If this all sounds a pretty negative take on the motorcycle which dominated the 2003 World Superbike Championship, don’t take it as such – it’s just that it required a higher level of rider expertise to get the most out of the bike than from its less performing, less capable, less powerful predecessors, and as speeds and power outputs mounted irresistibly, that was only to be expected.

Give Neil and Ruben credit for what they achieved aboard such a demanding, not yet fully developed, new motorcycle.

However, given that the 999 was after all developed firstly as a streetbike aimed at resolving the compromises of its 916-to-998 predecessors in everyday road use, I couldn’t help wondering if the overall package wasn’t maybe less than ideal for slick-shod Superbike racing, including the current position of the swingarm pivot, as well as the shape of the fuel tank determining the rider’s position, neither of which the team could then adjust under Superbike rules without 150-off re-homologation. Remembering that Carl Fogarty’s first World title on the then-new 916 came only after its wayward handling was resolved mid-season with chassis modifications, so give Neil and Ruben credit for what they achieved aboard such a demanding, but effectively not yet fully developed, all-new motorcycle.

The key factor in allowing them to do this was that wonderful engine, easily the main event in riding this Superbike.

The key factor in allowing them to do this was that wonderful engine, easily the main event in riding this soon-to-be-a-champion Ducati Superbike. This was the latest development of the ultra short-stroke 104 x 58.8mm Testastretta desmo V-twin motor which powered Troy Bayliss to runner-up slot in the title series in 2002, then fitted in the old-style 998R chassis. But Ducati’s ongoing R&D had delivered an even more impressive package, whose appetite for revs without sacrificing any of the desmo V-twin’s legendary torque, but indeed augmenting it, was literally awe-inspiring.

How Ducati’s ingenious R&D team had managed to get those soup-plate sized 104-bore pistons revving safely to the soft-action 13,700rpm revlimiter as a matter of course was already pretty praiseworthy (Lavilla’s 73-bore four-cylinder Suzuki ran just 300rpm higher, by comparison) – but to do so in an engine which pulled hard from as low as 4,000rpm, and had a completely linear and extremely deceptive build of power over what was almost a 10,000rpm power band, was literally astounding.

“The way the power built so fast but predictably, accompanied by the flat yet distinctive blat from the underseat exhaust’s single silencer with the more mellow boom from the old 998’s twin Termignonis, was the F03’s principal asset.”

Yet that’s what the 999 F03 would do, as demonstrated once I convinced myself it was better to use a gear higher almost everywhere at Misano than I’d been fooling myself into thinking was necessary. That meant, until I started pushing the 16.5-inch front tyre harder in the right turn across from the pits, that the engine would run that low in second gear, yet still drive sort-of OK down the next short straight. While probably the only places in a race you’d ever run the engine that low would be at the stupid walking-pace chicanes at Silverstone and Monza, the fact that it took that treatment in its stride was already impressive. But dial up at least six grand on the digital tacho and you were rewarded with serious drive out of the turn that would remind you to pull the Ducati upright if you wanted to avoid spinning the back wheel.

Yet the way the power built so fast but predictably, accompanied by the flat yet distinctive blat from the underseat exhaust’s single silencer that contrasted with the more mellow boom from the old 998’s twin Termignonis, was the F03’s principal asset. Despite the impressive power-to-weight ratio of 189bhp at 12,500rpm delivered by a bike scaling right on the 164kg twin-cylinder weight limit, the Ducati had such a smooth, torquey power delivery that you got a shock when you glanced at the tacho and saw the engine was already revving to 11,000rpm – there was no real sense it was spinning that hard, and no undue vibration of any kind to give you a reminder it might be. Tap the race-pattern powershifter – a bit abrupt for my tastes, not as smooth as the one on Greg’s Suzuki – once the readout got near the 13,500 mark, and you’d be rewarded with half-an-octave change in the exhaust note, and just as much power and torque as you had before. Impressive.

The Ducati’s gearbox was as smooth as dolcelatte, even changing from second to bottom gear as I initially did when braking hard into the pair of chicanes at Misano, without a hint you were passing through neutral as you did so.

The Ducati’s gearbox was as smooth as dolcelatte, even changing from second to bottom gear as I initially did when braking hard into the pair of chicanes at Misano, without a hint you were passing through neutral as you did so. Though Neil told me he never changed the internal gear ratios – why bother, with such a flexible motor? – it was noticeable that the F03 was geared pretty high, making a 100mph bottom gear almost a certainty with such a wide spread of power.

He used just the bottom five gears at Misano, and after experimenting I found it was better to short-shift at around 11,500 rpm in fourth just before the last of the three left-handers leading onto the main straight, which made the` Ducati run a tighter line through it, pulling hard. Then, brake hard and back down through the gears from the 150-metre mark for the 180° left at the end of the straight, pull it up properly before you got too enthusiastic with your right hand, try and copy the trademark Hodgson body English peeping the opposite way round the fairing to counter the wheelie it’d try to pull on you – and just revel in that fantastic acceleration, as the rear Michelin bit into the tarmac. Seriously fast.

Despite still being a work in progress at the time of my ride, the 999 F03 really was quite some Superbike package, a twin-cylinder racer-with-lights certain to have the beating of many open-class MotoGP contenders.

Despite still being a work in progress at the time of my ride, the 999 F03 really was quite some Superbike package, a twin-cylinder racer-with-lights certain to have the beating of many open-class MotoGP contenders, yet a bike which anyone with the money and the right connections could buy and race in 2004 in RS04 customer replica form. Full marks to Suzuki for challenging the dominance of this fine motorcycle, and coming so close at least once that year at Monza to beating it. Close – but no cigar….but two years later with restrictors junked, the tables were turned with Troy Corser scoring Suzuki’s first World Superbike title in 17 years of trying. But that’s another story…..

Neil Hodgson’s 2003 Ducati 999 F03 Tech Talk

The 999 F03’s 104 x 58.8 mm 90° desmo V-twin Testastretta engine was a direct descendant of the motor in the previous year’s 998 F02 (as raced in 2003 by HM Plant’s James Toseland and Chris Walker), but with modified camshafts, titanium valves and Pankl conrods, and revised mapping for the single-injector Marelli EFI, aimed at improving low-down performance as well as delivering a little more peak power, now up to 189 bhp at 12,500 rpm.

This was delivered courtesy of the 60mm throttle bodies homologated as a kit part (the stock 999 used 54mm ones, and had the restrictor rule gone ahead, as a twin the Ducati would have been forced to wear 50mm intake restrictors the following season), and an ultra-trick all-titanium tubone (as in ‘big tube’!) 2-1-2-1 exhaust, up to 65mm in diameter compared to the previous year’s 60mm system, and with the twin end pipes running into a single titanium-wrap under-seat Termignoni silencer, which must have featured extensive internal baffling to allow such a meaty exhaust to beat the noise police.

The large radiator, which featured an offset slot for the front cylinder to poke through, incorporated a triangular-shaped oil cooler in its lower section, as well as an air duct to the right of the cylinder head which fed cool air to the rear cylinder’s upper camdrive. That’s because the short-stroke engine was now revving so hard that the belts could overheat and stretch, altering the valve timing!

The large radiator incorporated a triangular-shaped oil cooler in its lower section, as well as an air duct to the right of the cylinder head which fed cool air to the rear cylinder’s upper camdrive.

The carbon fibre airbox and inlet ducts had been redesigned, in accordance with the new 999 styling which had been wind-tunnel developed for racing by British F1 aerodynamics guru Alan Jenkins, creator of the Desmosedici V4 Ducati’s Cagiva V594-inspired bodywork. The result was a bike both slimmer and svelter than the 998 with the rider in place, which was all that really counted. However, the original riding position which both riders appeared with in the opening round at Valencia, whereby a 25mm-plus seat pad jacked them higher in the air to load up the front end more with their body weight, had since been scrapped – reportedly on the insistence of the Ducati marketing department…..!

The 999’s all-new tubular-steel Verlicchi spaceframe was originally braced with a pair of strengthening tubes running parallel to the bottom of the fuel tank on each side, in a misguided attempt to stiffen the frame. Only one thing wrong: it made it TOO stiff, and after a sequence of crashes suffered by both riders without any warning (a problem also encountered by Troy Bayliss in 2002, for the same reason, which ultimately cost him the World title after his penultimate-round crash at Assen), this was removed and the open frame ends plugged with carbon caps.

As Colin Edwards proved by winning the 2002 World Superbike crown on a Honda whose previously ultra-stiff frame had been deliberately turned into a flexi-flyer, riders need a bike that ‘talks’ to them, and the looser frame Hodgson had raced with that season had said all the right things. This had the same adjustable steering head angle as before, ranging from 23.5° to 24.5d, with Hodgson invariably running the wider rake with lots of trail (around 100mm), in order to gain stability under braking – same reason he liked the longer, part-cast, part-fabricated conventional swingarm design by then used on the 999, operating an Öhlins shock and replacing the 998’s trademark monobraccia single-sided swingarm.

This still pivoted in the engine crankcase as well as the chassis, and though Ducati claimed there was provision for the position to be altered, it didn’t appear to have a very great range of adjustment, and in any case they owned up to not having had any time to experiment with this!

The 999 F03’s 43mm TIN-coated Öhlins fork ran quite a stiff spring to avoid bottoming out under heavy braking, with a 52/48 per cent weight distribution which was higher than before for a Ducati V-twin – one reason for the radiator being wrapped around the front cylinder, since the engine was as far forward in the chassis as possible without the fork legs touching it under heavy braking.

On Neil Hodgson’s bike that came courtesy of Brembo four-pot radially-mounted calipers gripping a pair of 305mm ventilated steel discs – the largest diameter auto-cooled rotors the Italian brake specialist had available, which Neil opted for to avoid overheating and subsequent brake fade, and also have the side benefit of reduced gyroscopic effect compared to the conventional unventilated 320mm discs Ruben Xaus opted for. There was a 218mm rear disc which Ruben used much harder than Neil, and Michelin had now standardised 16.5-inch rubber at both end, with the rear of the two Marchesini wheels employing a 6.25 in. rim at every track.

An important spinoff from the Fila-sponsored Ducati factory team’s irresistible march towards a tenth World title for the Italian marque in 2003 was the development of the first customer version of the new bike, with the 999RS available for purchase by privateer teams for 2004, closely based on the 999 F03.

2003 Ducati 999 F03 WorldSBK Specifications

ENGINE: Water-cooled DOHC 90-degree V-twin four-stroke with four valves per cylinder and toothed belt desmodromic camshaft drive, 999cc, 13.5:1 Compression Ratio, Magneti Marelli electronic fuel injection and engine management system, with single injector per cylinder, differential EPROM mapping and two 60rrm throttle bodies, 104 x 58.8m bore x stroke, 6-speed gearbox, Multiplate dry ramp-type slipper transmission

CHASSIS: Chrome-moly tubular-steel space frame, Front: 43mm inverted Öhlins telescopic forks Rear: Composite cast/fabricated aluminium swingarm pivoting in engine crankcases and chassis, with rising rate linkage and Öhlins shock Front: 120/60-420 (16.5-inch) Michelin on 3.50 in. Marchesini wheel Rear: 19/67-420 (16.5-inch) Michelin on 6.25 in. Marchesini wheel, Front: 2 x 305mm Brembo ventilated steel discs with four-piston radially-mounted Brembo calipers Rear: 1 x 218mm Brembo steel disc with two-piston Brembo caliper

PERFORMANCE: 189hp@12,500rpm, 166kg with oil/water, no fuel , 312km/h top speed (Monza 2003).

OWNER: Ducati Corse, Bologna, Italy.

2003 Hodgson Ducati F03 WorldSBK Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.