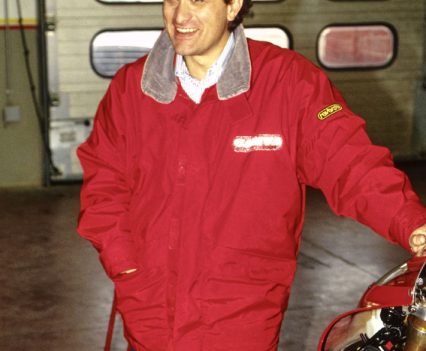

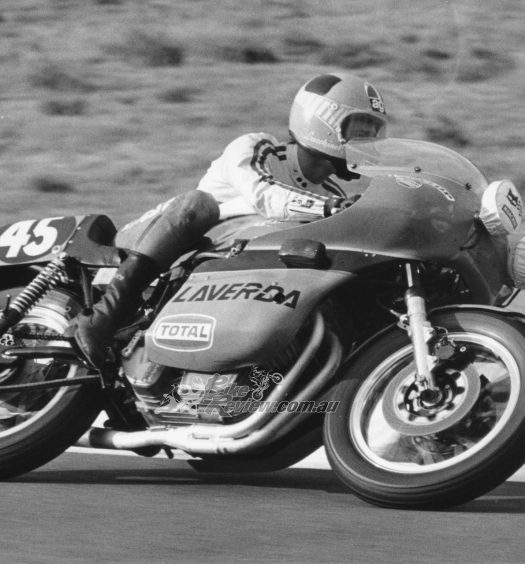

The Cagiva V592 represents resilience from the Italian team and genius from Eddie Lawson. Alan tested the beast after Cagiva's first 500GP win, exactly 30-years ago... Photos: Phil Masters

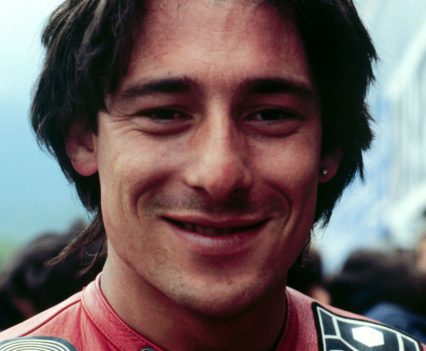

On July 12th, 1992, a modern two-wheeled fairy-tale came true. In a brave and tactically brilliant display of wet-weather riding on a drying track, four-time World champion Eddie Lawson won the 500cc Hungarian GP on a Cagiva, their first GP win in 12 years of trying.

There are few goose-bump moments that are quite like Cagiva’s first ever Grand Prix win, 12-years in the making.

After the race was halted after the first lap by a thunderstorm, the restart saw all riders on full wets – except Lawson, who fitted a front intermediate and rear cut slick. The first few laps on a sodden track tested Eddie’s skills to the limit, with no rear grip and carbon brake discs that barely worked.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

But he soldiered on in seventh place, over a minute behind leader Randy Mamola, until halfway through the race it started to dry. Just four laps from the end, Lawson sliced past a dumbfounded Doug Chandler’s Suzuki to take the lead and win the race, scoring Cagiva’s first ever GP victory.

Eddie was a master of his craft, being able to tame the wild Cagiva V592 on a patchy track was proof of that…

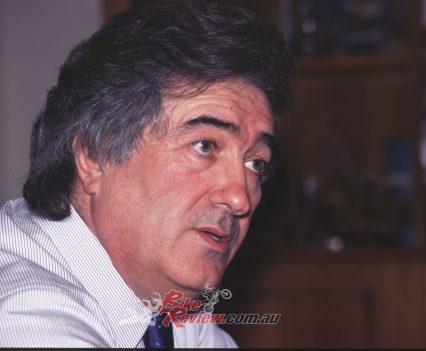

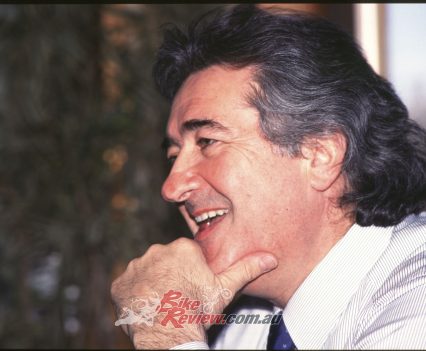

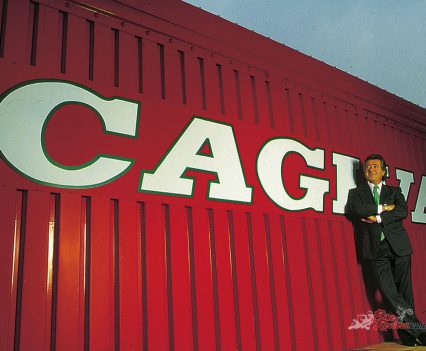

You didn’t have to be an Italophile to savour the impact of this achievement, which was as much applauded in the race shops of Cagiva’s J-rivals in Hamamatsu and Saitama, as it was back home in Varese. For Lawson’s win represented an overdue reward for all the billions of lire, millions of man hours and immeasurable enthusiasm poured into the Cagiva 500GP project over those dozen years by the Castiglioni brothers, Gianfranco and Claudio.

When Eddie Lawson took the chequered flag first in Hungary aboard the fiery red Cagiva, it was the fulfilment of a decade-long dream for the two brothers who, fifteen years earlier, as bike-mad tifosi steeped in Italian race lore, had tried to purchase the remains of the glorious MV Agusta race team when Count Corrado Agusta pulled out of racing at the end of 1976.

When Eddie Lawson took the chequered flag first in Hungary aboard the fiery red Cagiva, it was the fulfilment of a decade-long dream for the two brothers.

But the upstarts were turned down, for Agusta preferred to see MV die in peace rather than let a couple of rich kids take over the glorious four-cylinder four-stroke ‘fire engines’. (In a supreme irony, the Castiglionis later acquired the rights to the MV Agusta motorcycle name, and brought it back to the marketplace in a modern-day history that’s still unfolding, now under Russian ownership).

Check out our test on the 1993/1994 Kocinski Cagiva V593 here…

Undaunted, the Castiglionis bought an RG500, painted it in the MV race colours, and entered Marco Lucchinelli on it in 1978 GPs, the same year that they purchased the old Aermacchi factory beside Lake Varese from Harley-Davidson and renamed it Cagiva, after their father Castiglioni Glovanni.

Tackling the might of Japan Inc. at World Championship level might have seemed a futile ambition back then, but the Castiglionis were crazy enough to try. They assembled a top team of experienced engineers, and added to their numbers over the years as the development of the line of Cagiva 500GP racers evolved, starting with the first such bike which debuted in 1981.

After initially struggling to even qualify for a 500GP grid, the Cagiva gradually improved relative to the Japanese bikes.

After initially struggling to even qualify for a 500GP grid, the Cagiva gradually improved relative to the works Japanese machines, to the point that the brothers became convinced that all that stood between them and their dream of beating Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha in 500cc GP racing was the lack of a truly top rider on their bikes. That man duly arrived in 1991 in the shape of four-time World champion Eddie Lawson, and after a try-out test he signed a two-year contract to race the red Italian bike, with Alex Barros as understudy.

“Had Fast Eddie not agreed to ride for the team, it’s likely the Castiglionis would have chosen to concentrate on Superbike racing where they were already World champions with their other brand, Ducati.”

Instead, history records that, in the sunset of his GP career, Lawson proved the key to revitalizing Cagiva’s GP effort in a way that the Castiglionis had certainly hoped for. The reduced response time of the Varese race shop to Lawson’s input accelerated development above the level of the Japanese, especially after the arrival of ex-Formula 1 engineer Riccardo Rosa to coordinate the Italian factory’s GP race effort from the ’92 season onwards. But before that, two key objectives were met thanks to Lawson’s efforts – both on home ground at Misano, in the 1991 Italian GP.

There, Eddie qualified a Cagiva on the front row of the grid for a 500GP race for the first time, and led the race for the first lap in front of an ecstatic crowd, en route to a first-ever rostrum place for Cagiva in the dry. Seventh place in the points table at the end of the year was Cagiva’s best-ever result, even if the season tailed off with some front-end tyre problems shared with fellow Michelin users, Honda.

“Seventh place in the points table at the end of the year was Cagiva’s best-ever result, even if the season tailed off with some front-end tyre problems shared with fellow Michelin users, Honda.”

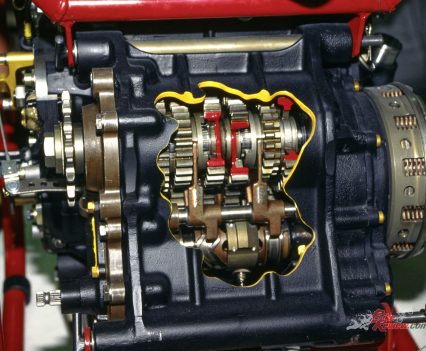

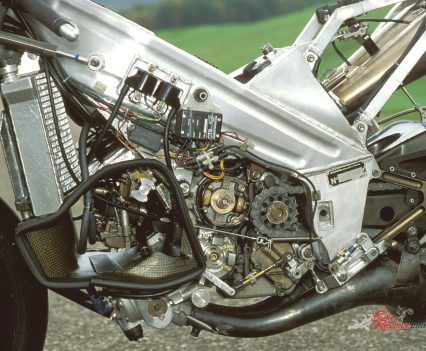

But with 169bhp@12,000rpm now available, and a bike right on the new 130kg weight limit, the V591 Cagiva – now with a wider 80° angle between the cylinders of its crankcase reed-valve V4 motor with twin contrarotating cranks, to improve the inlet shape and increase total reed box area – was truly on the pace, and matched its Japanese rivals for technical sophistication.

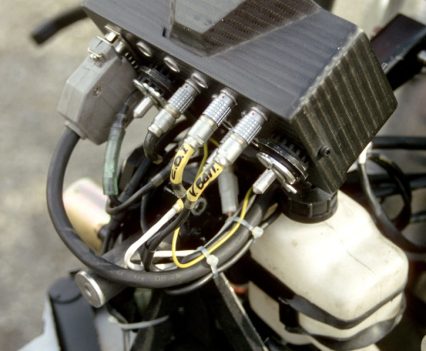

The Kokkusan digital ignition now adopted had programmable EPROM chips for variable ignition timing, there was 15 per cent more power at 8,000rpm than before, yet for the first time a usable overrev of 12,800rpm – all key factors in exploiting the engine’s potential. And under Lawson’s urging, chassis designer Romano Albesiano – today the Technical Director of Aprilia’s MotoGP team – had produced an all-new chassis in just four days of flat-out work that gave more stable, measured handling. Finally, the Cagiva was now a potential race-winner.

In 1992 that hope became reality, after a slow start to the season which saw Lawson and Barros struggling with problems of power delivery and grip – most likely thanks to the adoption of Dunlop tyres and Showa suspension for the first time, for which the team needed time to develop a setup. But after Honda had reminded them of a similar idea they’d already had years before with the square-four C9 engine, at Assen in June Cagiva introduced their own Bombardone version of the ’92 NSR500’s Big Bang engine concept, and immediately passed another milestone, when Lawson put a Cagiva on pole there for the first time ever in a 500GP race, only to crash out of that race in a controversial incident while battling for the lead with Kevin Schwantz.

But it took only until the next race for the V592 to achieve that long-awaited debut Cagiva GP victory in Hungary – and in doing so Lawson had finally given substance to the youthful dreams of a pair of race-mad enthusiasts blessed with the financial means to realise their desires.

Eddie’s subsequent pole position for the British GP at Donington proved Hungary wasn’t a fluke, and riding his Dunlop-shod V592 Cagiva GP-winner at an end-of-season test session at Mugello only a couple of weeks after I’d tested its Honda NSR500 and Suzuki RGV500 rivals, underlined the extent of the Italian team’s achievement.

For the first time in ten years of test-riding each year’s Cagiva 500GP racer in succession, I could confirm the Italian bike was now for the first time truly comparable with its Japanese factory rivals. In the previous decade there’d been promising highs (1987 with de Radiguès and Roche regular points scorers with the Bastos-sponsored bikes, 1991 when Lawson joined) and despondent lows (1985 with a heavy bike’s razor-edge powerband, a flawed package repeated in 1989). But after Lawson’s arrival, everything started coming together in a big way – it only needed a rider the team could believe in, who also believed in the bike.

“For the first time in ten years of test-riding each year’s Cagiva 500GP in succession, I could confirm the Italian bike was, for the first time, truly comparable with its Japanese factory rivals”

That year they did so – and, with the debut at Assen of the Bombardone (literally, Big Bang in Italian!), Cagiva actually leap-frogged ahead of Yamaha, who were slower to react to the changing technical order in GP racing, and even Suzuki, whose similar narrow firing-angle engine didn’t seem to work as well as the Italian bike’s.

After Lawson’s arrival, everything started coming together in a big way – it only needed a rider the team could believe in, who also believed in the bike.

But although Honda deserves the credit for introducing the Big Bang era to 500GP racing, it wasn’t its engineers’ idea in the first place to close up the firing order in terms of crankshaft rotation, in search of improved traction and rideability. For Cagiva also built a Bombardone version of their rotary-valve square-four 500cc motor as far back as 1985, when engine designer Ezio Mascheroni tried to solve a persistent traction problem by reducing the gaps between the firing strokes.

Cagiva then fitted the result into their C9 chassis, and tester Massimo Broccoli covered many kilometres on the result, during which he discovered what Honda demonstrated to everyone in 1982: big bangs equal good grip. But though the engine delivered the same power on the dyno as a conventional motor, there was one big problem preventing Cagiva from ever racing the Bombardone.

The V592 represented millions of dollars in development, kick started simply out of a love for racing.

Having the cylinders firing so close together made it impossible for the rider to push-start it by himself, even when warm – the back wheel would lock every time, with the sort of compression ratio needed to produce good horsepower. Since all GP races in those days began with push starts, this was a big enough handicap to rule out the idea – one Mascheroni didn’t return to until 1992, after Honda had reminded him how well it worked! This explains how Cagiva was able to produce the V592 Bombardone motor in just ten weeks after hearing and seeing the Honda in action for the first time at the start of the season, in Suzuka.

So on to my test, and Cagiva boss Claudio Castiglioni must have had a direct line to the Vatican, and thence to the Man Upstairs. How else to explain that for my Mugello ride on Eddie Lawson’s GP-winning V592, he’d arranged for an almost dry track for my first session while I got used to the bike, then for the second, damp but drying track conditions exactly resembling those prevailing in Hungary on the day the Castiglioni brothers’ dream came true, using the intermediate tyres that Eddie won his GP on?! Such efficiency…..

Actually, the mixed track conditions offered a fuller understanding of just what a milestone in Cagiva’s GP development the Bombardone big bang engine represented, as well as an appreciation of how much solid development the team had invested in that year, ever since I’d ridden their V591 Lady in Red at a damp and slippery Pergusa track in Sicily 12 months earlier. That bike was already a vast improvement over its snatchy sisters from the pre-Eddie era, with their sudden throttle response, peaky power delivery, narrow usable power band, and total lack of overrev.

“The mixed track conditions offered a fuller understanding of just what a milestone in Cagiva’s GP development the Bombardone big bang engine represented.”

For the first time, you could hold a gear with a Cagiva race engine, and allow it to run up to 800rpm over the peak power mark before it started to struggle – a vital feature back then where so many new tracks like Magny-Cours had such short straights, and so many turns. But the big improvement was at the other end of the revscale, where under constant prompting from Eddie Lawson, engine designer Ezio Mascheroni and his team of engineers had succeeded in smoothing out the power delivery low down, and upping power at low revs, which in 500GP racing meant 7-8,000rpm upwards.

However, they weren’t done yet, because the V591 Cagiva motor wasn’t perfect – the engine was still snappy enough in midrange to unhook the back wheel very easily in a turn when the power came in strong, plus the whole power curve had too many layers – maybe not outright holes like before, which’d make the bike bog down out of corners, but a lack of a continuous, linear shove that had definitely affected acceleration. Even before the mid-season arrival of the Bornbardone, Cagiva had already done much to remedy this defect on their ’92 motor, which had the same basic design as its predecessor, but the Big Bang version took care of the rest. The result was now an engine that, if it still didn’t quite have the top end power and appetite for revs of a Honda or Yamaha, was at least as good everywhere else.

Alan reported that the Cagiva didn’t quite have the revs of its Japanese competition but was a drastic improvement over the brands earlier bikes.

Just riding down pit lane at Mugello, I realised at once what a big improvement Cagiva had wrought. Firstly, although the Bombardone motor still vibrated a bit through the bars and footrests, thanks to its circa-80° firing angle for all four cylinders, it was apparently a lot better then than when first tested, and certainly vibed no worse than Schwantz’s similar-format RGV500 Suzuki I’d ridden a couple of weeks beforehand. What tingles that remained didn’t intrude on your riding the bike, but as I accelerated out of any of Mugello’s chicanes, I realised what a real improvement in both traction and usability the latest Cagiva engine represented.

“As I accelerated out of any of Mugello’s chicanes, I realised what a real improvement in both traction and usability the latest Cagiva engine represented.”

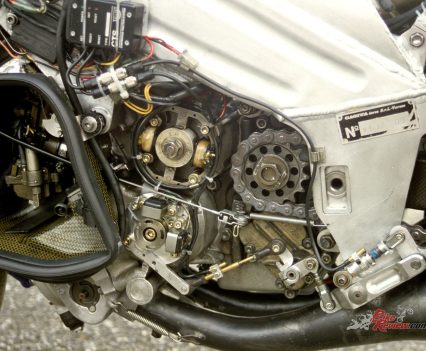

It’d drive cleanly from as low as 6,500rpm – the exhaust powervalve started to open at just 6,000 revs, exceptionally low by Japanese standards, and didn’t rotate fully open till just over 10,000rpm, an unusually wide range of operation. The electronic wizardry through which the operation of the cylindrical powervalve was linked to the ignition curve, gear selected, engine speed and throttle position, was surely responsible for the smooth yet potent way the Cagiva engine picked up speed from low down, combined with the cylinder design (five different versions were used for the ’92 season), and exhaust pipe (two different types employed that year).

Gone were the layers of power that made the bike seem to falter slightly when accelerating hard – but gone too was the sudden rush of power around 9,000rpm that had made it too easy for the back wheel to step out on a damp track at Pergusa a year earlier. Instead, there was a lovely, linear pull from way low to quite high, the sort of torquey delivery that had the front wheel waving lazily in the air in any of the bottom three gears if you whacked the throttle wide open out of turns. No wonder Eddie found the bike so effective on a damp track en route to victory in Hungary.

“Gone were the layers of power that made the bike seem to falter slightly when accelerating hard – but gone too was the sudden rush of power around 9,000rpm.”

The reason you could do this was because of the excellent traction the Bombardone motor layout delivered. Riding a bike delivering 174bhp at the gearbox on a damp track isn’t something you can ever say is easy, but this was the first time I’d ridden a Big Bang 500cc V4 engine in the wet, and whereas before this would have been a prime reason for total cop-out with the throttle hand until you felt you were reasonably upright and more or less straight, now I could start to kid myself that just maybe I could ride the Cagiva hard in the damp without it biting back.

In the dry, the Cagiva was as user-friendly and tractable out of turns as I’d expected after riding the Big Bang Honda and Suzuki – but it was in the wet that it was a real eye-opener. The extra bottom end power, combined with the smoother delivery of the V592 motor and the increased traction of the Bombardone firing layout, delivered so much confidence. Even when I got carried away and used a little too much throttle, the back wheel just spun up a little, as controllably as on a four-stroke Superbike of the era, and it was relatively easy to calm everything down. On the old Cagiva ‘screamer’ motor, getting the back end stepped out in the wet was a recipe for disaster, but with the new-style motor there were no such inhibitions – this was a major advance in promoting rider confidence.

The Cagiva felt a lot more refined in its power delivery than before, with strong power coming in smoothly around 8,000rpm – 1,000 revs lower than in ’91 – and an evenly progressive increase up to the 11,900rpm peak power ceiling. But hold a gear, and the engine pulled to 12,800rpm before it really ran out of poke – an acceptable amount of overrev, though the motor didn’t rev as high as the Honda or Suzuki, since everything happened 500rpm further down the rev scale.

The Cagiva also didn’t pick up engine speed as fast as the Japanese bikes, perhaps because of crankshaft inertia, or porting – it had done so the previous year in midrange, but Cagiva had now unlayered the power delivery, and spread everything out more. So the delivery was smoother, but it took more time to build revs. The Italian bike’s acceleration felt slightly more leisurely than the Honda or Suzuki, but top speed was good down the kilometre-long Mugello front straight, though, and watching Lawson and Schwantz in combat at Assen, it had been evident that the Cagiva had more pace than the Suzuki on ultimate top end, as well as coming out of tight turns such as the Assen chicane a little better, thanks to the improved low down power delivery.

“One bad habit the gruff-sounding Bombardone motor sucked you into easily was to be fooled by the lazy-seeming motor into riding it like a Ducati, using a gear too high much of the time.”

One bad habit the gruff-sounding Bombardone motor sucked you into easily, though, was to be fooled by the lazy-seeming motor into riding it like a Ducati, using a gear too high much of the time. You had to mentally force yourself to use one ratio lower, so as to maximise the power delivery and get optimum drive out of turns. Sure – it’d pull OK in a higher gear, but not as fast or as well as if you cogged down and used the fat part of the power curve to maximize acceleration.

Of course, in the wet the fact that the engine was so tractable was a big asset – especially if I had to cut the throttle for a moment as I ran over one of the several junior rivers running across the track down a Mugello hillside, then got back on the power again to regain drive. Get brave when back on the gas again, and I discovered I could wheelie it in the wet quite comfortably thanks to the good grip from the Dunlop rubber, but try that before, with the old 180° V4 engine, and I’d have been on my ear….

Like the works 125/250 Aprilias on which the system was developed, Eddie Lawson’s Cagiva was fitted with the Tellert solenoid-equipped CTS powershifter, the first of its kind that we now take so much for granted. Having ridden all the Aprilias fitted with it, I have to say the Cagiva probably benefited even more from the CTS – upshifting with the throttle wide open allowed you to focus on the bike’s handling, without the subconscious distraction of having to work the throttle back and forth to change gear.

It was pretty amazing how much of their own money Cagiva plunged into this bike. Simply shod in Cagiva red with minimal sponsorship on the bike.

The traditional notchy Cagiva gearchange was a little better than before, and in fact its rather mechanical action actually helped – you don’t want too light a change with any powershifter, else you may change gear without really meaning to! One surprising fact which revealed just how wide the power band was on the V592 was that Lawson geared the bike to use just the bottom five ratios at Kyalami and Magny-Cours – never sixth.

The V591 Cagiva, set up for me at Pergusa just as Fast Eddie had raced it for the last time only weeks earlier, had felt really light and quick-steering, despite pretty conservative steering geometry by GP standards of the era, with a 25° head angle and no less than 104mm of trail – that’s a lot for the 1990s, when 15-20mm less was the norm, with less rake, too. But this gave Lawson the high speed stability he wanted, yet without heavying up the steering, or making the bike understeer under power. But when I came to sample its V592 successor at Mugello, the only real disappointment was how heavy it felt changing direction in anyone of the trio of chicanes.

Alan reported that he had to wrestle the Cagiva V592 side to side through the corners more than the championship winning NSR500.

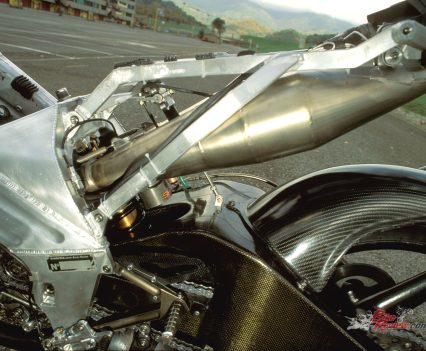

This may have been a function of weight distribution rather than steering geometry, but it definitely needed a good tug to lift it over from side to side, where Mick Doohan’s ‘92 NSR500 Honda, for example, had felt much less physically hard to steer. As against this, the Cagiva was definitely much less twitchy in fast corners than the previous year’s bike, and it also handled bumps better – the car-induced ripples on a couple of Mugello sweepers didn’t upset it, especially on the last, long, long Bacine third-gear sweeper where you needed to get the power on early for maximum drive down that long straight. And if I hit the huge bump exiting the final Biondetti chicane just wrong with the power wound on hard, the Showa semi-active rear suspension coped brilliantly.

Especially impressive were the Cagiva’s dry-weather brakes, a pair of carbon Brembos fitted without shrouds and curiously enough of differential sizes – the left disc was a 280mm rotor, the right one a larger 320mm one. The Italian black brakes worked really well, with lots of sensitivity at light lever pressures, and max stopping available more or less instantly when you squeezed hard. They were also predictable in the sense that they didn’t gradually over-servo themselves when you used them hard, like at the end of the long main straight at Mugello, where they’d had plenty of time to cool off. There was a slight servo effect which could probably have been eliminated with a shroud like Honda used to maintain operating temperatures, but the Brembos were more predictable and effective than the snatchy AP brakes on the RGV500 Suzuki I’d tested a fortnight beforehand.

New for ’92 was the Cagiva’s LCD tacho, incorporated in the telemetry system with a quadrant-type sweep to the dial which at least made it easier to read than the similar but linear-scale tacho I’d had to struggle with on the works Bimota Tesi I’d been racing that year! This was very hard to read in sunlight, but the Cagiva’s was easier because the spaces between each 1,000rpm got wider as the redline approached, even if the numbers were too small to be easily seen. For sure, this was one piece of technology where new was not necessarily better – the old-type analogue tachos where you know just by glancing at the position of the needle how many rpm you’re using were much easier to get used to.

Cagiva weren’t consistently fast or successful, but they were always one of those teams that were out there racing genuinely for the love of it…

As riding their GP-winning bike told me, Cagiva had now learnt how to beat the Japanese at their own game, where what worked well was what really counted, not how elegant or technically innovative it looked. the man who was mainly responsible for bringing about this change in philosophy was Eddie Lawson, the greatest GP rider of his generation, who fired up the guys who two years earlier were so down and nearly out, who not only gave Cagiva their self-respect but also that of the GP paddocks and of enthusiasts around the world.

“It was job done for Fast Eddie, with the V592 Cagiva – a task that Aleix Espargaro looks set to be emulating 30 years on with the Aprilia RS-GP in MotoGP this season!”

Eddie brought Cagiva to the forefront of 500GP racing after a dozen long years in the no-hoper wilderness, and who did everything he said he intended to do when he signed up to ride for them in 1991/92, with pole position and a rostrum in the first season, a GP win in the second. It was job done for Fast Eddie, with the V592 Cagiva – a task that Aleix Espargaro looks set to be emulating 30 years on with the Aprilia RS-GP in MotoGP this season!

Eddie Lawson’s 1992 Cagiva V592 Racer Specifications

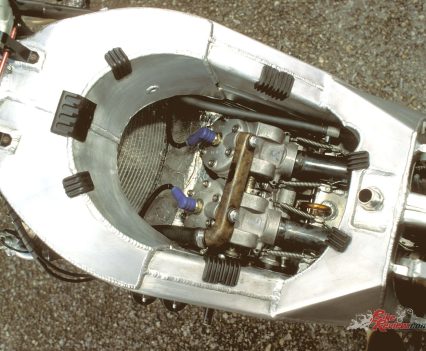

ENGINE: Watercooled 80-degree V4 crankcase reed-valve two-stroke, with twin contrarotating crankshafts and electronic powervalves, 499cc, 56mm x 50.6mm bore & stroke, Kokkusan electronic programmable digital CDI, 4 x 36 mm Mikuni dual-body twin-choke with electronic powerjet, 6-speed extractable gearbox with Multiplate dry clutch (7 steel/6 friction).

CHASSIS: Fabricated Carpental 7020 aluminium twin-spar, 43 mm Showa inverted telescopic forks (f) Carbon fibre honeycomb swingarm with single Showa electronic shock and progressive-rate link (r) 2 x Brembo carbon discs (1 x 320mm, 1 x 290mm) with four-piston Brembo calipers (f) 190 mm Tilfon carbon disc with two-piston Brembo caliper. (R) 3.10/4/80-17 Dunlop KR106 radial on 3.50in cast aluminium Marchesini wheel (F) 185/55-17 Dunlop KR108 radial on 6.25in cast aluminium Marchesini wheel. 25 degree head angle. 1400mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 174hp@11,900rpm (at gearbox), top speed 304km/h(Hockenheim 1992), 130kg dry.

Owner: Cagiva Corse, Schiranna, Varese, Italy.

Eddie Lawson’s 1992 Cagiva 500GP Racer Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.