What would go down in history as the best selling Ducati almost didn't happen. Alan had the chance to throw a leg over the pre-production Monster back in 1993... Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura.

The Ducati Monster opened up a whole new world for the Italian brand. Pulling them out of a financial slump to become one of the most popular machines the brand has ever seen. I was one of the first people outside of the factory to ride it back in 1993…

The Ducati Monster opened up a whole new world for the Italian brand. Pulling them out of a financial slump to become one of the most popular machines the brand has ever seen.

Originality of design is at least as much a gift as a science, especially when it comes to concocting a new kind of motorcycle that nobody else did before. But the problem is that you never really know till you’ve translated your ideas into metal if it’s all going to work out right, for one man’s flight of fancy can be another’s passport to oblivion – weird, rather than wonderful. Even then, the ultimate accolade awaits: the verdict of the buying public in the Showroom GP.

Read up on the history of the Ducati Monster here…

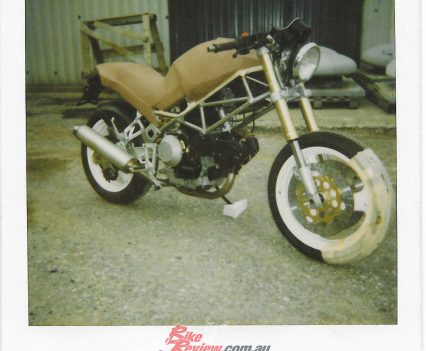

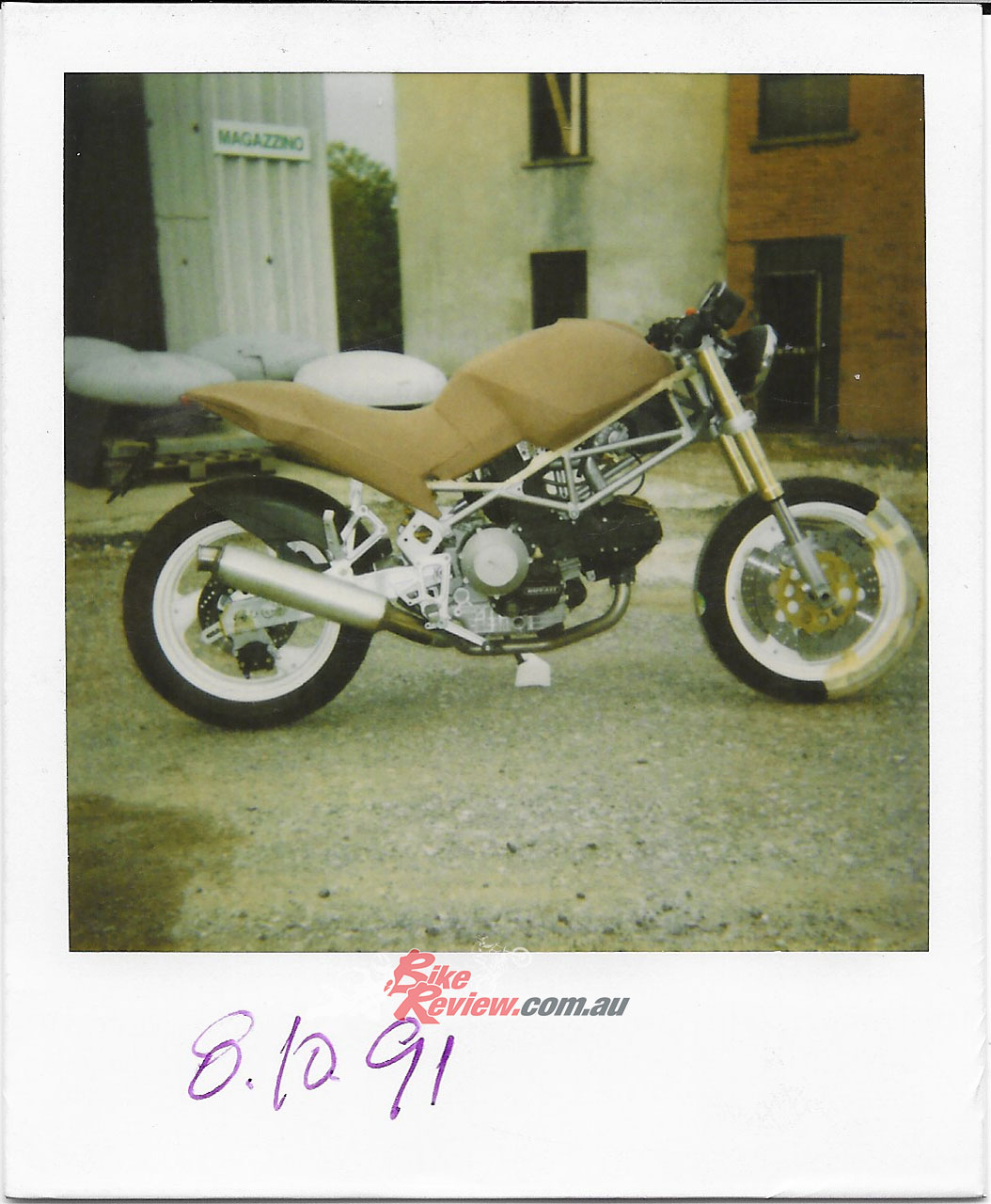

On that basis, exactly 30 years ago Italo-Argentine progettista Miguel Angel Galluzzi must have been a mighty relieved man after the acclaim accorded to his Ducati Monster, as it began to reach dealer showrooms around the world early in 1993. This came after he was finally able to build the bike for which he’d had the sketches in his mental briefcase for ages, ever since he’d left Honda’s Italian design studio three years earlier to join the Cagiva Group. Selling it to their Ducati subsidiary’s commercial department had been tough – for this was a motorcycle powered by a desmo V-twin engine that was radically different than anything Ducati had ever built before. As in – Not a Sportbike. But eventually Galluzzi got the go-ahead – and the Ducati M900, aka the Monster, was born.

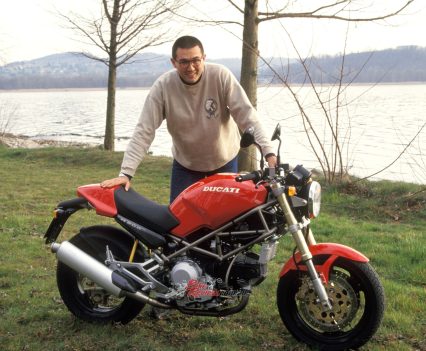

Even then, there were those at Ducati unconvinced of the bike’s sales potential – a fact reflected in the tentative production figure originally projected for the new bike for its debut model year in 1993 – a measly 1,000 bikes. That was scaled up almost hourly when the M900 was launched at the Cologne Show in October 1992 to a rapturous reception from press and public alike, but the final ceiling of 3,000 machines that was all Ducati ended up producing the following year left many distributors and dealers round the world crying in their Chianti glasses.

This motorcycle is not only the best-selling Ducati model ever, it’s also the one which saved the Italian manufacturer from going bust in the 1990s.

They sold over 1,500 Monsters in Italy alone in 1993, while in the UK the original order for just 400 bikes, instead of being doubled, had to be scaled down to half that, all of which were spoken for by eager customers long before a firm price had even been announced. It was a similar tale around the world – Australia, always a key export market for Ducati V-twins, received a mere 40 first-year Monsters. The marketplace verdict on Miguel’s deviant desmo was a decisive thumbs-up.

The chance to be the first outsider to ride the bike came about six weeks later than originally intended, in February 1993, as suppliers scrambled to come up with the components needed to build the bike much sooner and in greater numbers than originally foreseen. But the chance to spend a day with Monster no.000001, shipped fresh off the Bologna assembly line to the Cagiva factory beside Lake Varese where it had been concocted by Galluzzi in the space of a few months with the aid of a single helper, supplied an answer to the final question still remaining in the M900 equation: did the go match the show?

“The chance to be the first outsider to ride the bike came about six weeks later than originally intended, in February 1993, as suppliers scrambled to come up with the components needed to build the bike much sooner.”

Well, as the past 30 years have repeatedly confirmed, anyone who didn’t find riding the M900 both a hugely enjoyable and also an addictive experience, would be better off driving a car. I hadn’t ridden another streetbike for a very long time which succinctly encapsulated the fun factor in motorcycling, magnified by the fact that this was such a practical, versatile bike – what the Italians call polivalente.

Well, as the past 30 years have repeatedly confirmed, anyone who didn’t find riding the M900 both a hugely enjoyable and also an addictive experience, would be better off driving a car…”

OK, you wouldn’t want to ride from Bologna to Amsterdam on it in winter – but for sure it was a bike you knew you’d look forward to throwing a leg over for a quick blast to the pub or the shops, or a longer spin in town or country, with or without your best girl on the back. Sexist? Sure: this was a red-blooded, Latin street rod par excellence – but one that the prescient Claudio Castiglioni was targeting at female riders via the low seat.

“OK, you wouldn’t want to ride from Bologna to Amsterdam on it in winter – but for sure it was a bike you knew you’d look forward to throwing a leg over for a quick blast to the pub or the shops.”

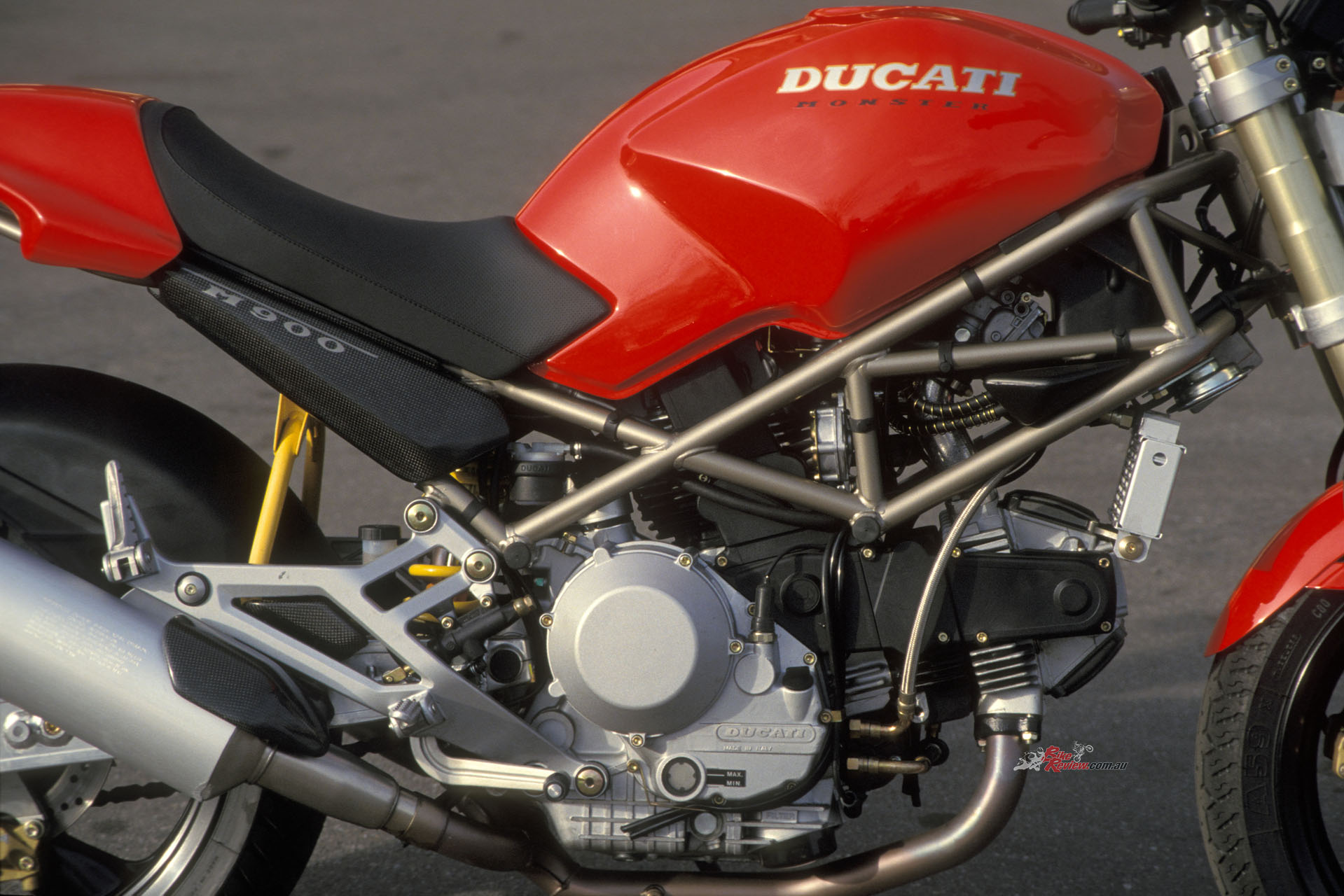

To concoct his V-twin variant, Galluzzi had taken the 900SS’s air-cooled desmodue motor and fitted it in a chassis comprising the front half of a 750/900SS frame, mated to an all-new rear end derived from the 888 Superbike’s, to achieve the rakish look and muscular mien his desmo dreambike was intended to have, with a fully-adjustable monoshock controlling a relatively skinny 170/60-17 Michelin radial fitted to a 5.50in three-spoke cast wheel rather surprisingly made by Brembo.

They also equipped the Monster with a set of their floating 320mm discs and four-pot calipers up front (with a 245mm fixed steel disc on the rear), matched to a 3.50in front wheel wearing a 120/70-17 Michelin, and a 41mm upside-down Showa fork that somehow looked streets more butch and hunky fitted to the Monster than it ever did on the 750/900SS models it was developed to adorn. Powering this parts-bin plot was an unmodified 92 x 68mm 904cc two-valve oil/air-cooled desmodue motor, exactly as fitted to the 900SS, in which guise it developed 73hp@7000rpm at the wheel, running on 9.2:1 compression and safe to nine grand if you really insisted.

Powering this parts-bin plot was an unmodified 92 x 68 mm 904cc two-valve oil/air-cooled desmodue motor.

However, that’s where the smart stuff started, because by cleverly adorning this kit of parts sourced from existing Ducati models with his minimalist street rod styling, Galluzzi had created a bike that was not only unlike any other Ducati ever made, it also then had no competition from anything else in the marketplace. As a sportbike with bodywork deleted, it was simply unique.

OK, you could distantly relate the new Monster to the Yamaha V-Max born back in 1985 and still selling well, the Italian bike was a) a twin, not a four, b) handled properly in turns, and c) had that uniquely Italian touch of class that the brash, flash megaMax had no pretence to claim. The Monster was no mammoth, in spite of its chunky appearance, but instead yet another demonstration of the flair of Italian designers for proportion, coupled with originality, and there was no greater moment of awareness of this art than when you threw a leg over the M900 for the very first time, and got the shock of your life. It was tiny!

Galluzi somehow managed to make the Monster look like this big, mean machine while parked. But, accessible to a range of people to ride…

What looked in photos or even in metal to be a meaty, muscular motorcycle turned out to be reet petite from the rider’s seat, almost delicate in its stature, clothed in a lean-looking leotard Designed by Galluzzi that showed all the good stuff while preserving modesty, a bit like seeing Schwarzenegger dressed up in drag.

Sitting there with the short, flat bars in front of you and your knees tucked neatly into the tank recesses, with the footrests a bit further back than I’d expected, it seemed the Monster was so short, it ended two inches in front of your nose – just where the round, shallow, classic-looking headlamp met the compact dash comprising just a speedo and a block of (highly legible) warning lights.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

Classic-looking, did we say that headlight was? Not just the look, for Galluzzi admits he sourced it from a 1973 Laverda SF750, and Ducati just happened to have a stock itself left over from the 900 Darmah bevel-drive model which also used to wear it. The tricky bit was persuading CEV to dig out the patterns and make it again in bulk – which they did.

But there was nothing historic about the way the Monster performed. The secret was in the riding stance and the dynamic qualities of the bike, because besides lowering the overall gearing a couple of teeth on the rear wheel, Ducati had made no mechanical modifications versus the 900SS, with which the Monster shared the same six-speed gearbox.

“There was nothing historic about the way the Monster performed. The secret was in the riding stance and the dynamic qualities of the bike.”

Rather surprisingly, the 185kg declared dry weight for the unfaired M900 was actually a couple of kilos more than the faired 900SS’ 183kg in stock form, which if true may have canceled out some of the improved acceleration gained by the lower gearing. But the Monster felt infinitely wieldier than the SS, in spite of the slightly longer 1430mm wheelbase which didn’t do much to help keep the front wheel on the ground if you give it a big dose of gas off the mark. This bike was a wheelie-hound!

Rather surprisingly, the 185kg declared dry weight for the unfaired M900 was actually a couple of kilos more than the faired 900SS’.

But the steeper 24° head angle and reduced 98mm trail make it noticeably faster-steering than any Ducati built since Barry Sheene stopped racing – as it happens, not as much of an irrelevance as you might think, since our Bazza indeed received one of the first Monster to arrive Down Under. If it was good old 000001, let’s hope they replaced the silencers which I nerfed either side in only mildly spirited cornering, even with the preload jacked up to gain max ride height. Though the final 1993 production version of the cans was more oval than those on the Cologne Show bike, so as to gain ground clearance with a slimmer design, it wasn’t enough. It wasn’t till Ducati chamfered the silencers on the 1995 model that you could take full advantage of the bike’s excellent handling in turns, mated to the sticky grip of the 59X Michelins.

For the Monster was always much more than just the straightline muscle-twin its appearance may have deluded you into thinking it to be. Taut and together-feeling at all speeds, it responded with paradoxical delicacy to rider input at low speeds, yet was stable and reassuring going fast. The steering was always quick and direct, making it an ideal city bike – same as now. But for sure that first version was geared too high, probably because Ducati’s R&D mob still figured it to be a sportbike sans bodywork. Which it was – but one that also had to live in towns, where another two teeth on the rear sprocket would have reduced the unwelcome amount of transmission snatch.

But that wasn’t the main drawback of riding the Monster in traffic – working the stiff and unprogressive clutch lever hard would gradually seize up your left hand. Actually, a five-speed gearbox would have been better suited to the Monster’s nature, especially as the torquey V-twin motor pulled from way low, and packed the same meaty midrange punch as all other desmodue models did back then. Even though it cruised quite happily at 150 km/h-plus on the autostrada – where thanks to the slightly reclined riding position, you didn’t have to hang on to the ‘bars too hard – the Monster was actually quite comfortable at those speeds. This was really a town and country bike for short hops, rather than long ones where sixth gear might come in handy.

No criticisms about the suspension, though – it felt superb, with the progressive action of the rear Boge monoshock soaking up bumps and ridges with surprising ease in spite of the short 110mm of wheel travel, to give a comfy ride that exceeded expectations for a bike that looked as muscular and angry as this one. The Showa fork was softly damped, with a 120mm excursion, but even hitting a bump just after the apex of a downhill turn with the suspension fully compressed didn’t upset the handling at all. This was a confident, capable motorcycle to ride hard on, especially with the excellent brakes which were both sensitive and totally effective, making the Monster a point and squirt bike supreme. It wasn’t a good idea to use the rear brake too eagerly, though – else you’d send the back wheel chattering into turns as the V-twin engine’s inertia reminded you what you were riding.

Though you might have cared to stand on the pegs and stretch your legs a couple of times an hour if you were relatively tall, the riding position and seat were pretty comfortable even for a taller rider – though the longer-legged brigade might have trouble slotting their knees into the tank recesses. But this isn’t a tourer, after all, and on the short runs the Monster was mostly likely to be used for, the close-coupled riding position delivered a great sense of control.

“The Monster felt toy-like to ride, the narrow, flat bars giving instant steering response, coupled to the well-chosen steering geometry that allowed you to choose your line with precision.”

The Monster felt almost toy-like to ride, the narrow, flat bars giving instant steering response, coupled to the well-chosen steering geometry that allowed you to choose your line with precision, then depend on that surefooted suspension to ensure the bike stayed there. This was a hot rod that steered, stopped and handled like a racer, while that meaty desmo motor pumped out torquey power you could call on instantly, thanks to the smooth response of the Mikuni carbs which had so totally transformed the two-valve Ducati motors’ character since the dark days of the wobbly Webers just a few years earlier. And, though the stiff clutch wasn’t as progressive as a bike used mainly in town demanded it to be, the gearshift was slick and quick, with ratios that were well-matched, if one too many.

“This was a hot rod that steered, stopped and handled like a racer, while that meaty desmo motor pumped out torquey power you could call on instantly…”

Massimo Bordi modestly refused to be photographed with Miguel Angel Galluzzi alongside their joint creation after coming out into the grey February day to ask my opinion of it on my return to the factory: “It was all his idea, his work and his perseverance that produced this bike, not mine,” said the Cagiva Group technical boss and Ducati chief engineer, “so please give him all the credit.” Except, when I did, I got told off by Cagiva’s PR department for giving Miguel a name check on the grounds that “It’s not our policy to identify the name of any of our designers in connection with a specific model. Please in future only say that it is the work of our Cagiva design team.” Honestly….!

For in giving birth to the Ducati Monster, Galluzzi not only added an extra dimension to the Ducati range which allowed customers enjoy the fun and brio of desmo V-twin motorcycling without feeling obliged to pretend they were Ducati’s World Superbike champion Doug Polen each time they twisted the wrist. He also created a new style of performance motorcycle, one that already back then you could see would become as vital an aspect of urban chic as Raybans and Timberlands – or Harley-Davidson.

The designer desmo that the Monster represented was a Euro-style boulevard cruiser for the ’90s – an alternative rather than a challenge to the Harley lifestyle image…

The designer desmo that the Monster represented was a Euro-style boulevard cruiser for the ’90s – an alternative rather than a challenge to the Harley lifestyle image. You already knew after riding it that every manufacturer in the world would end up copying it – but while imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, the original is almost always the best. And the Monster was – and still is – exactly that. Complimenti, Miguel Angel!

1993 Ducati Monster M900 Specifications

ENGINE: Air and Oil-cooled, 4-stroke, Twin-cylinder, 90° L-type, Belt driven desmodromic single-cam, 2 valves per cylinder, 904cc, 9.2:1 compression ratio, 92 x 68mm bore x stroke, 2x Mikuni BDST38 carbs, 6-speed gearbox, Dry, multi-plate, hydraulic operated clutch.

CHASSIS:Tubular steel space frame, 41mm inverted telescopic fork Showa (F) Swingarm with mono-shock (R), Double disc brakes, 320 mm, 4-piston calipers (F) Single disc, 245 mm, 2-piston caliper (R), Brembo wheels 120/70-ZR17(F) 170/60-ZR17 (R), 1430mm wheelbase

PERFORMANCE: 55 kW@8250rpm, top speed 215km/h (Monster I.E.) 184KG dry.

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.