Last week we ran Sir Al's test of the JJ-Cobas TB5, a bike that took on the big guns and won the world title in 1989. This week we take a delve into the back story... Photos: Emilio Jimenez

Alex Criville’s story to becoming a MotoGP icon is a brilliant one. As a bike mad teenager, he basically made it all happen himself and with raw talent, sheer guts and a bit of smart thinking he became the legend he is today. The JJ-Cobas TB5 played a crucial role.

Scene One: In 1984, a 14-year old bike-crazy kid from Barcelona, Spain, fakes his older brother’s signature on a form so he can go racing aboard his 80cc moped, stripped and prepped for competition.

Scene Two: cut to two years later, when the very same kid wins the 1986 Spanish road racing championship for such bikes, admits to his true age, and is promptly signed up by the all-powerful Derbi team to go racing for them in 1987, mainly in the 80cc European Championship, but with the odd Grand Prix race thrown in. He finishes second in his first GP, his home race at Jerez, but pressures of life as the low man on the totem pole in a four-rider Derbi squad are already starting to be apparent.

Read Alan’s test of the JJ-Cobas TB5 125cc GP racer here…

After some inevitable friction when he almost loses his teammate Julian Miralles the 80cc Euro-crown by having the audacity to beat him in a key race, it appears he may get his marching orders. But instead, it’s Miralles who leaves, and The Kid stays with Derbi for 1988, finishing second in the 80cc World Championship to teammate and three-time World champion, Jorge Martinez ‘Aspar’, winner of six of the seven rounds.

But in doing so he’s irredeemably antagonised Derbi’s star rider by failing to observe team orders on a couple of occasions, and this time he does get the boot – though maybe Aspar already had a pretty good idea of The Kid’s talent, and wanted him out as a potential threat to his supremacy in Derbi.

The Kid crosses the street and signs for Derbi’s bitter fellow-Barcelona rivals JJ-Cobas…

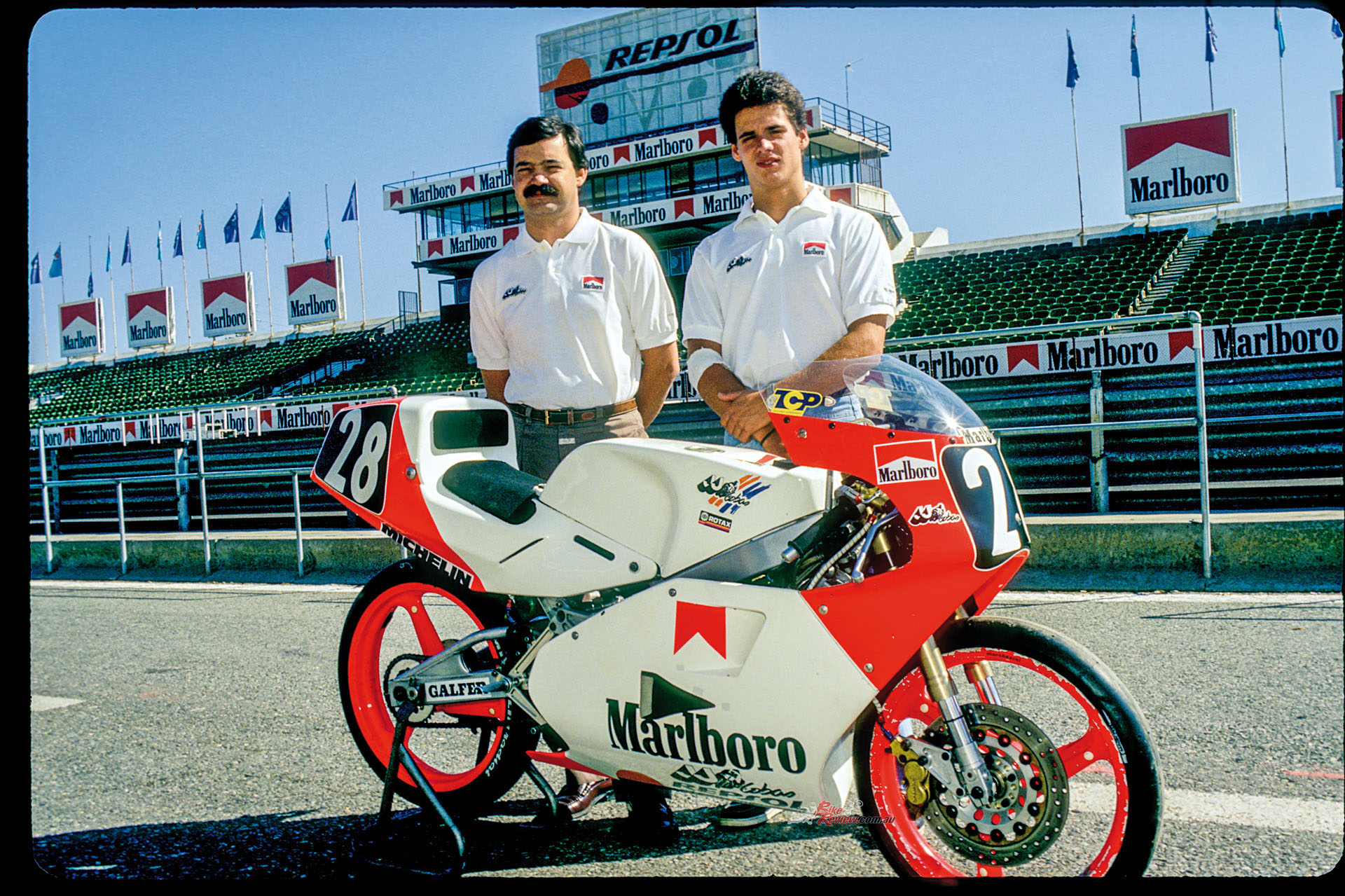

Scene Three: 24 hours later, The Kid crosses the street and signs for Derbi’s bitter fellow-Barcelona rivals JJ-Cobas, to contest the 1989 125cc World series with sponsorship from Marlboro, and in direct opposition to defending champions Aspar, Derbi, and sponsor Ducados, a rival Spanish tobacco brand.

Scene Four: The Kid beats Aspar and Derbi in their first confrontation in a Spanish title round at Jerez the month before the GP season begins, setting a new lap record. Scene Five: disaster – The Kid crashes in practice for the first 125GP round of the season in Japan, breaks his collarbone and can’t start. Scene Six: two weeks later in Australia, with the injury scarcely healed, he stuns the GP world by winning his first 125GP race on the brand-new JJ-Cobas – the brand’s debut class GP victory. Scene Seven: one month later, The Kid proves it’s no fluke by winning again, this time in his home GP at Jerez in front of 120,000 voluble Spanish fans – to the inevitable discomfiture of Derbi and Aspar.

It is amazing what Antonio Cobas, Alex Criville and the team achieved in such a short period of time.

Scene Eight: a fortnight later, he crashes out of the Italian GP at Misano, after attempting an impossible manoeuvre to take the lead in a bitter three-way duel for victory with factory-supported Honda riders Ezio Gianola and Hans Spaan. Well, say the paddock pundits, what do you expect – he’s just a kid! Scene Nine: The Kid wins again in the very next race in Germany – and now even the pundits are starting to take him seriously.

Scene Ten: one more GP win in Sweden and three further cannily-ridden second places later, cut to Czecho, scene of the final GP of a 12-race season. The Kid holds the title lead, and need only finish sixth or better to win the World crown. Instead, he scores a brilliant and emphatic victory at Brno, to become the then-youngest ever World champion in motorcycle road racing history, at the age of 19 years and five months. His name: future 500cc World champion Alex Crivillé. Cut – it’s a wrap….!

In emulating Johnny Cecotto’s feat in becoming World champion at the age of 19, with five GP victories to his credit, Alex Crivillé (pronounced Cree-vee-lay, not Criv-ill) did more than prove that life often imitates art, and that truth is equally exciting as fiction. In winning the first World title ever achieved by the rider of a Rotax-powered motorcycle, defeating not just the might of the well-funded Derbi squad but also the even more mighty factory Honda team run by HRC, Crivillé also brought a well-deserved reward at World championship level to arguably the most influential chassis designer in Grand Prix history, Antonio Cobas. He also rewarded the commitment of the most dedicated and enthusiastic sponsor anywhere in the two-wheeled world of the time – Jacinto Moriana, aka ‘JJ’, the bike-mad proprietor of a major Barcelona car dealership empire, JJ Automóviles. Oh, sorry – I almost forgot

Scene Eleven. Epilogue: cut to Jarama, just five days after Alex Crivillé clinched what proved to be his first but not his last World title at Brno on August 27, 1989 aboard the JJ-Cobas. With scarcely enough time after the long 2,000km drive home from Czecho to do more than change the tyres and gearing, the JJ-Cobas team have brought their title-winning 125 to Madrid for me to sample in an exclusive sole test at the Jarama GP circuit, with Alex and Antonio on hand as well to give me some added insight into how what was effectively a hand-made special built with a proprietary engine in a small workshop in Barcelona, managed to defeat the resources of such giants as Honda, Derbi and Aprilia to win a World title. How’s that for a happy ending?!

If Derbi’s success in wresting the inaugural 125cc single-cylinder World crown from Honda in 1988 was praiseworthy in terms of David defeating Goliath, the following year’s JJ-Cobas victory must be the ultimate achievement at World championship level of what the Italians call a moto artigianale – a bike built from proprietary parts by a single-rider privateer team using a self-built chassis. “Yes, and no,” said Antonio Cobas, as we waited for the mechanics to finish cleaning all the Czech flies off the bike before I ventured on track with it.

“Yes, we’re a much smaller team than Derbi, but in fact this bike that Alex has won the title on is a production JJ-Cobas TB5 that we developed during the season in the same way that any of our customers with similar resources could do. The bike is fundamentally no different from any of the 12 other TB5 production versions we sold this year, so rather than a triumph for the home special builder, our title represents a victory for Alex’s riding, and the engine development talents of Eduardo Giró.”

Indeed, because exactly 20 years after he amazed the GP world with the performance of his single-cylinder monocoque-framed Ossa 250 ridden to GP victory by the late, great Santiago Herrero, in 1989 one of the unsung wizards of two-stroke engine development also achieved his just reward of a World title. Eduardo Giró had been responsible not only for the remarkable reliability of the Rotax engine in the JJ-Cobas that season – the only mechanical breakdown, a piston that broke in the race at Spa, was due to what Giró discreetly termed ‘avoidable human error, not component failure’ (so, jetting?), but also for extracting Honda-beating horsepower from an over-the-counter motor.

How much? “Eduardo doesn’t deal in figures, so much as constant imp¬rovement,” said Cobas, “but we have a little over 40bhp at the gearbox at 12,800rpm, with maximum revs of 13,200rpm before the power falls off steeply. Sometimes we were fastest through the speed traps, sometimes the Hondas or the Derbi, but by the end of the season we were all very evenly matched on engine performance. What made the difference was the choice of gearing and carburation on race day – which is where Eduardo’s experience, and Alex’s increasing sensitivity, told in the end.”

The TB5 was the third in the series of 125cc JJ-Cobas designs, which began in 1987 with a version built to accommodate both the old parallel-twin MBA engine in the final year of the twin-cylinder 125 class, and the then new but as it turned out completely disastrous single-cylinder motor from the same Italian company. For 1988, Cobas turned to the new kart-derived Rotax engine – a logical move, really, given his close collaboration with the Austrian engine company throughout his GP career in the 250cc class, ever since building his first Cobas-framed Siroko-Rotax in 1980.

This led in 1981 to the ‘Kobas-with-a-K’ 250 which essentially invented the modern twin-spar aluminium chassis concept (Yamaha’s Deltabox design came a year later), and in 1983 Carlos Cardús won the 250cc European championship on a Kobas-Rotax. That year, Cobas teamed up with Jacinto Moriana to found a new company named JJ-Cobas, with the race team’s workshops fronted by a glamorous retail motorcycle dealership.

Future World champion Sito Pons duly gave the nascent JJ-Cobas brand its first Grand Prix victory with a win on home ground at Jarama in the 1984 Spanish GP, ending the season in fourth place in the championship. This established the Spanish company as the chassis manufacturer of choice for the 250GP privateer, always combined with Rotax engines, and even when Pons moved to race for Honda in the 250cc class in 1986, Antonio Cobas combined acting as his race engineer with continuing to develop and supervise the manufacture of customer racebikes, with Xavier Cardelús winning the 1987 European 250cc title on a Rotax-powered JJ-Cobas. So with Sito winning the 250GP World title in 1988 and 1989, with Cobas as his race engineer, Antonio was effectively slicing himself in half, competing against his 250GP customers with a factory Honda, while in 1989 building a better bike than the Japanese manufacturer’s to win the 125GP World title for his own company!

So for 1988, the first year of the new single-cylinder 125GP category, Cobas had built a series of 12 TB2 customer bikes with the new Austrian one-pot rotary-valve motor. But this originally suffered from the same problem as the MBA – considerable vibration, especially at the high engine speeds at which disc-valve engines like these makes their power. For 1989, Rotax resolved the issue by incorporating a gear-driven balance shaft in its new Type 128 engine, as well as fitting a new cylinder with revised porting offering improved midrange performance, a different cylinder head, and a 38mm flat-slide Dell’Orto carb. C

Cobas revamped the 1988 chassis slightly to accommodate the revised engine, while also altering the steering geometry and rear suspension link, as well as narrowing the bike by 30mm overall compared to its TB2 predecessor. Various other subtle changes were also made, including a slightly different seat and fairing both now made in carbon fibre, which cut the weight to just 66.5kg half-dry (versus the 65kg class weight limit), fitted in customer guise with a Forcella Italia fork, and a White Power rear shock.

Originally, the JJ-Cobas team had no intention of contesting the 1989 125GP World championship itself, since the TB5 had been designed as a customer racer, and as well as his work as Sito Pons’ race engineer, Antonio Cobas was advising the four-wheeled Minardi Formula 1 team on chassis design, in between developing a JJ-Cobas 250GP racer powered by the team’s own 250cc V-twin engine designed by Eduardo Giró, that was nearing completion after a three-year gestation. Busy man! But Crivillé’s sacking from the Derbi team changed all that, and when the decision was made to go GP racing that season, there were only three months before the first GP in Japan.

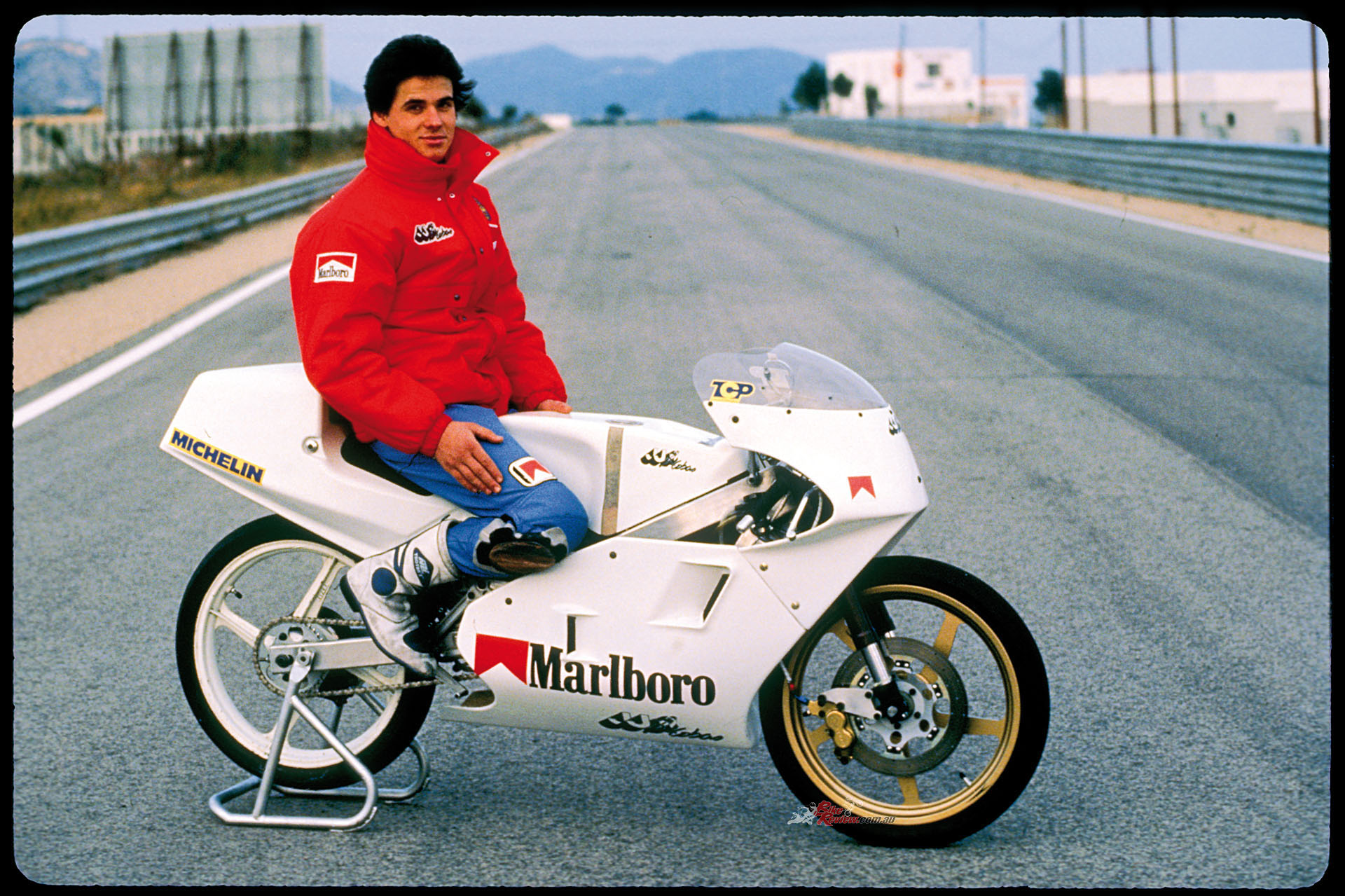

Accordingly, Crivillé’s bike was very close to standard for the first couple of races, even using 18-inch wheels and standard tyres to register its debut victory in Australia, before Michelin started supplying its special 17-inch rubber – a front crossply and radial rear – from the Spanish GP onwards. This required Antonio to alter the suspension and steering geometry to suit, but apart from that and the upside-down White Power fork that became available for that season, it was a stock TB5 chassis-wise, just a fraction heavier at 67kg half-dry.

Eduardo Giró’s work on the stock Rotax engine was only slightly more extensive, concentrating on expanding the usable power band, and improving overall performance. He retained the standard five transfer/three exhaust eight-port Rotax cylinder without modification, but bored the Dell’Orto flat-slide carb out to 39mm, and modified the crankcase to permit a larger inlet tract with altered rotary valve for different port timing. Long hours on the test bed produced a new exhaust pipe that the team ended up racing with all season long, even though Giró brought slightly different ones to almost every race for them to try.

But the stock Rotax pistons were replaced with special Mahle ones to give a higher compression, matched by new cylinder head inserts. A carbon fibre airbox was developed to optimise carburation, but a key modification was to replace the standard radiator with a much bigger one constructed out of a Renault 5 Turbo unit, to enable the Rotax engine to run as low as 45ºC, Giró’s ideal temperature reading. That’s real cool, man….

These modifications raised the standard Rotax engine’s 38.5bhp output at the gearbox to just over 40bhp, a figure marginally improved still further when, like most other Rotax teams, Giró tried the motor without the balance shaft fitted. The power expended in driving the shaft was thus restored, and in fact Crivillé won his first GP in Australia with the bike in this form. “But the power gain was so small as to be insignificant – less than 1 bhp,” said Cobas. “Refitting it not only made the bike much less tiring to ride, it also gave the chassis an easier time.

We didn’t run it like that again.” Considering that broken engine mounts had been a frequent problem on the 1988 JJ-Cobas TB2, as with other Rotax-powered bikes that season before the balance shaft was fitted, this was probably just as well, but the vibration also affected the carburation at high rpm as well, the consequent aeration making the decision an even more logical one. “Once we saw how competitive we were in Australia, our policy from then on was to take as few risks as possible mechanically,” explained Cobas. “We had to make sure the bike would finish each race, and that meant sacrificing possible performance gains if we weren’t completely certain of their reliability.”

To finish first, you must first finish, is an old racing axiom that Derbi, which suffered many engine failures on the mechanical front, and Honda’s lead rider Gianola, who crashed several times, seemed to have forgotten in 1989. It was this policy which prevented Crivillé from racing with the most significant engine modification that Rotax came up with during the course of the season at the first European GP, at Jerez in April. This was an electronic power-valve, controlled off the rev-counter by a pair of cables and a small Ni-Cad powered electric motor replacing the pneumatic power-valve traditionally used on the Austrian firm’s GP engines since the mid-‘80s.

This delivered more precise control over the operation of the valve, and slightly improved midrange performance as a result – but Cobas didn’t race with it till two rounds later in Germany (where Alex Crivillé also won, just as in Spain), by which time they’d tested its reliability to Giró’s satisfaction. Similarly, all season long the team employed the same standard Rotax digital ignition offering a choice of four different pre-programmed curves, rather than risk the more sophisticated but unproven computerised system specially developed for them in Spain by Motoplat, which presented an infinite choice of curves via a pre-¬programmable microchip. This had been found to offer superior power delivery in testing, but was never actually raced with. “We decided it would be nice to have something up our sleeves for 1990!” said Cobas.

“Getting dismissed by Derbi was the worst day of my life,” said Alex Crivillé as we bench-raced that evening as the sun went down behind the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains lining the horizon at Jarama. “I felt such a fool, as if I’d thrown away my one and only chance of becoming World champion. But the following day, when Jacinto and Antonio demonstrated their faith in me by establishing a team from the ground up simply to go Grand Prix racing with me – me! – as the only rider, it was like I’d been born again. I grew up into a man in those 24 hours, and stopped behaving like a child.

Then when I broke my collarbone in the very first race in Japan, I was disheartened, but not despondent. I knew the season was a long one, and that I could recover from that setback. I made sure from then on that I didn’t make any more mistakes, and except for. crashing in Italy, I don’t think I did. I’m so very grateful to JJ and Antonio for having such faith in me, and I’m glad I was able to repay them by winning the World championship for them. I just hope that it leads on to even better things in the future.”

Ten years on, in 1999 as a Honda 500GP factory rider, it indeed did….

1989 JJ-Cobas TB5 125 Specifications

Engine: Water-cooled, rotary-disc-valve single-cylinder pneumatic power-valve two-stroke, 54 x 54.5mm bore x stroke, 124cc, 39mm Dell’Orto flatslide carburettor, Rotax digital CDI, six-speed extractable gearbox, multiplate dry clutch (5 steel/4 fibre).

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar frame, WP 42mm inverted forks, box section alloy swingarm, WP shock, progressive rear link, 26º rake, 98mm trail (95-100mm), 1270mm wheelbase, 54/46% weight distribution without rider, single 280mm Zanzani steel disc with four-piston Brembo caliper, 180mm Zanzani alloy disc with two-piston Brembo caliper, Marchesini cast magnesium wheels 2.15 and 2.75in, 8/56 – 17in Michelin crossply front tyre, 10/59 – 17in Michelin radial rear tyre.

Performance: Weight 67kg with oil and water, no fuel! 232km/h top speed (Hockenheim)

Owner: Fundaciao Can Costa, Barcelona, Spain