With a Vincent Black Lightning going under the hammer at Bonhams Auctions on April 20-21, we thought it a great time to hear from Sir Al about the experience of riding such a mythical machine... Photos: Kel Edge & Bonham’s

More than 70 years ago the Vincent Black Shadow delivered the most performance from a street legal series production vehicle that money could buy – on two wheels, or four. Officially timed at 122mph, it outsped by 2mph the Jaguar XK120 sports two-seater…

The XK120 was then the world’s fastest production motor car (hence the model’s name), making the Shadow the first true Superbike of the modern era. Vincent’s countless road racing and speed record successes testified to the inherent performance wrapped up in the British firm’s 50° V-twin engine – so much so that attempts to run a 1000cc Clubmans TT in the Isle of Man foundered after just three races, all won by Vincents with the rest nowhere.

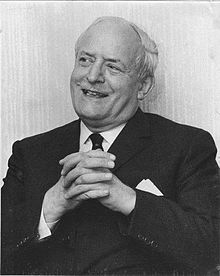

Indeed, in the final 1950 edition, only Vincents took part. Nothing else on two wheels could compete with the vivid performance and exceptional handling by 1950s standards delivered by the 998cc motorcycle created by legendary Australian engineer Phil Irving. The same man would later produce the Repco V8 engine which powered Jack Brabham and Denny Hulme to a pair of Formula One world titles in 1966/67, a decade after the sad demise of the Vincent marque.

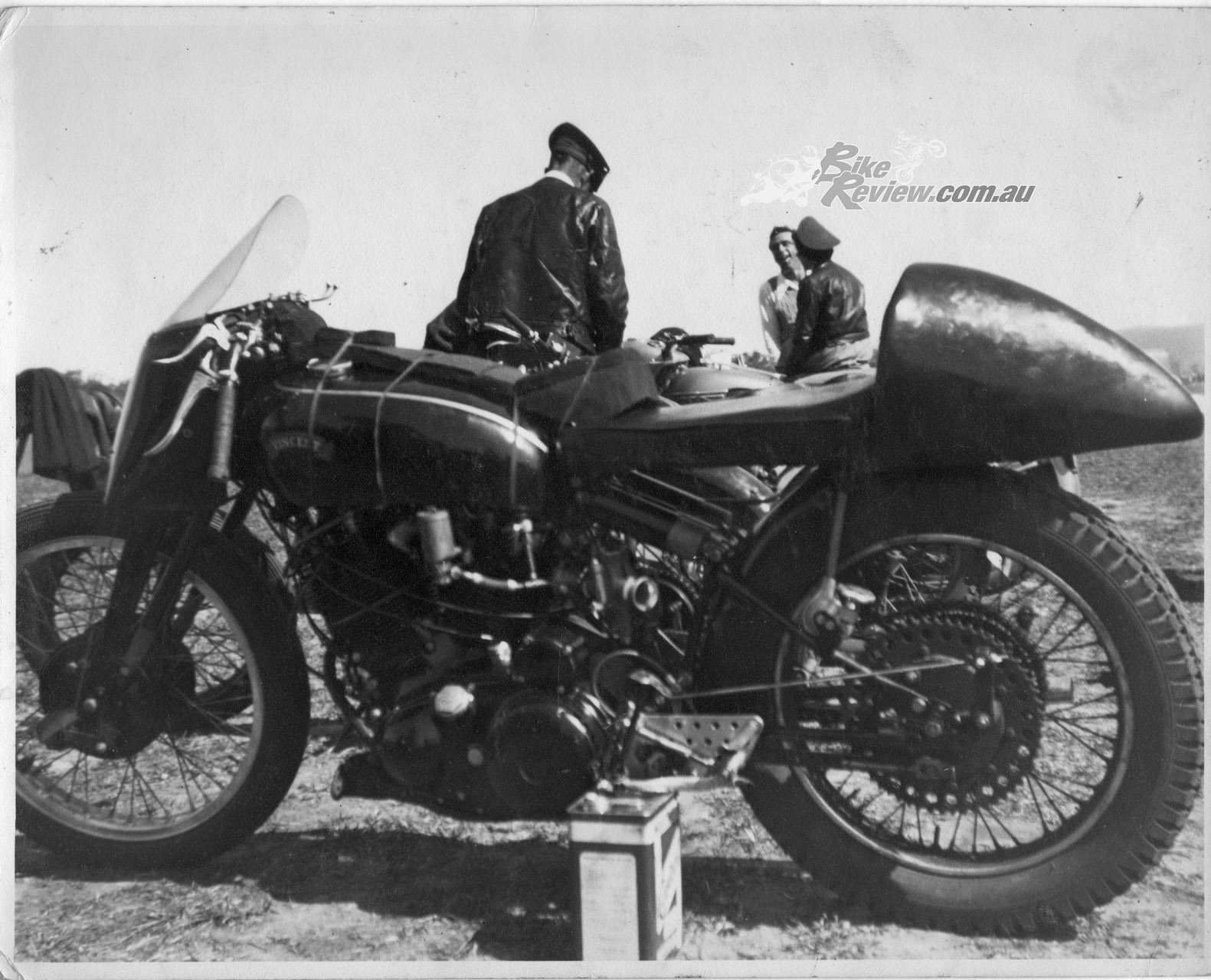

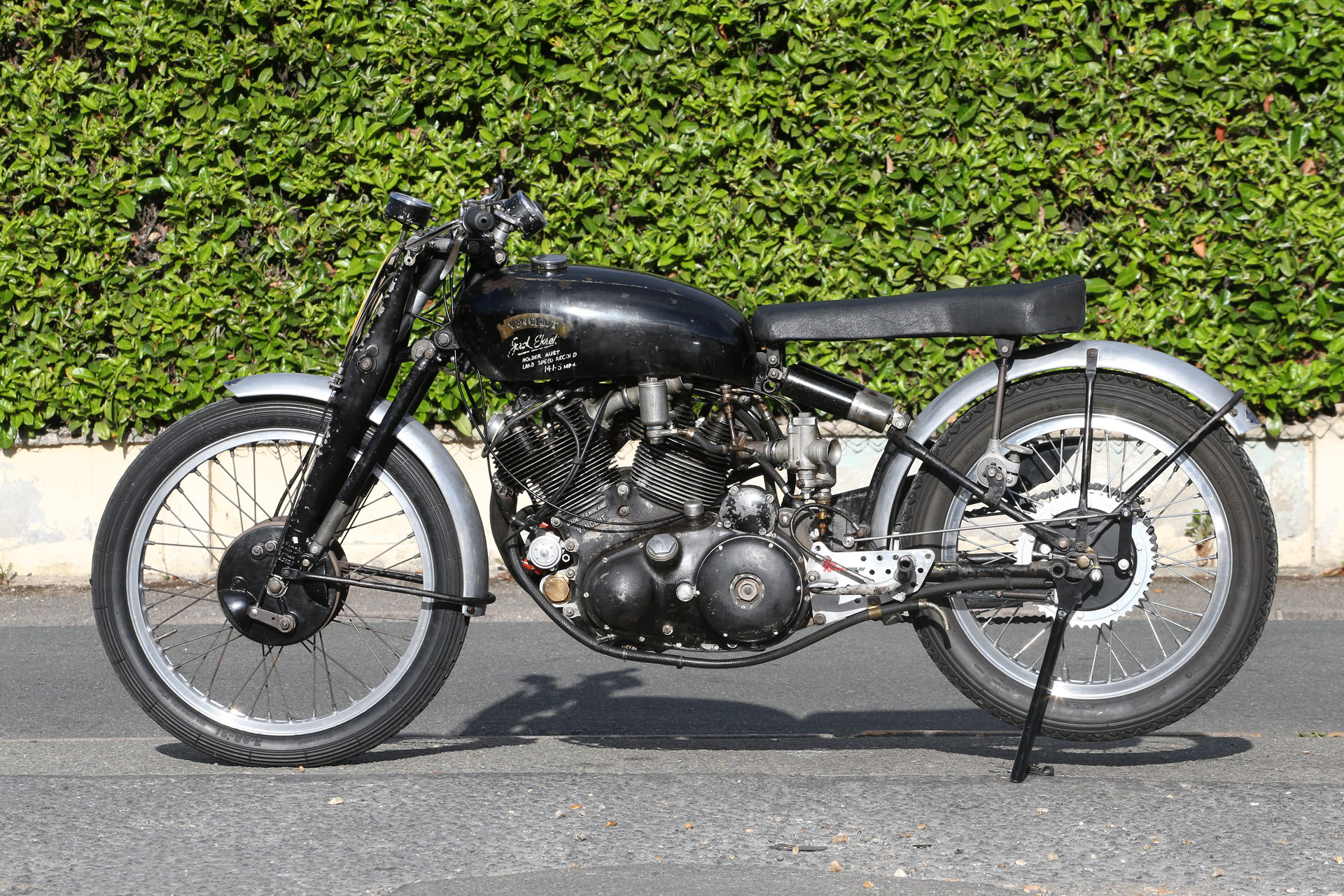

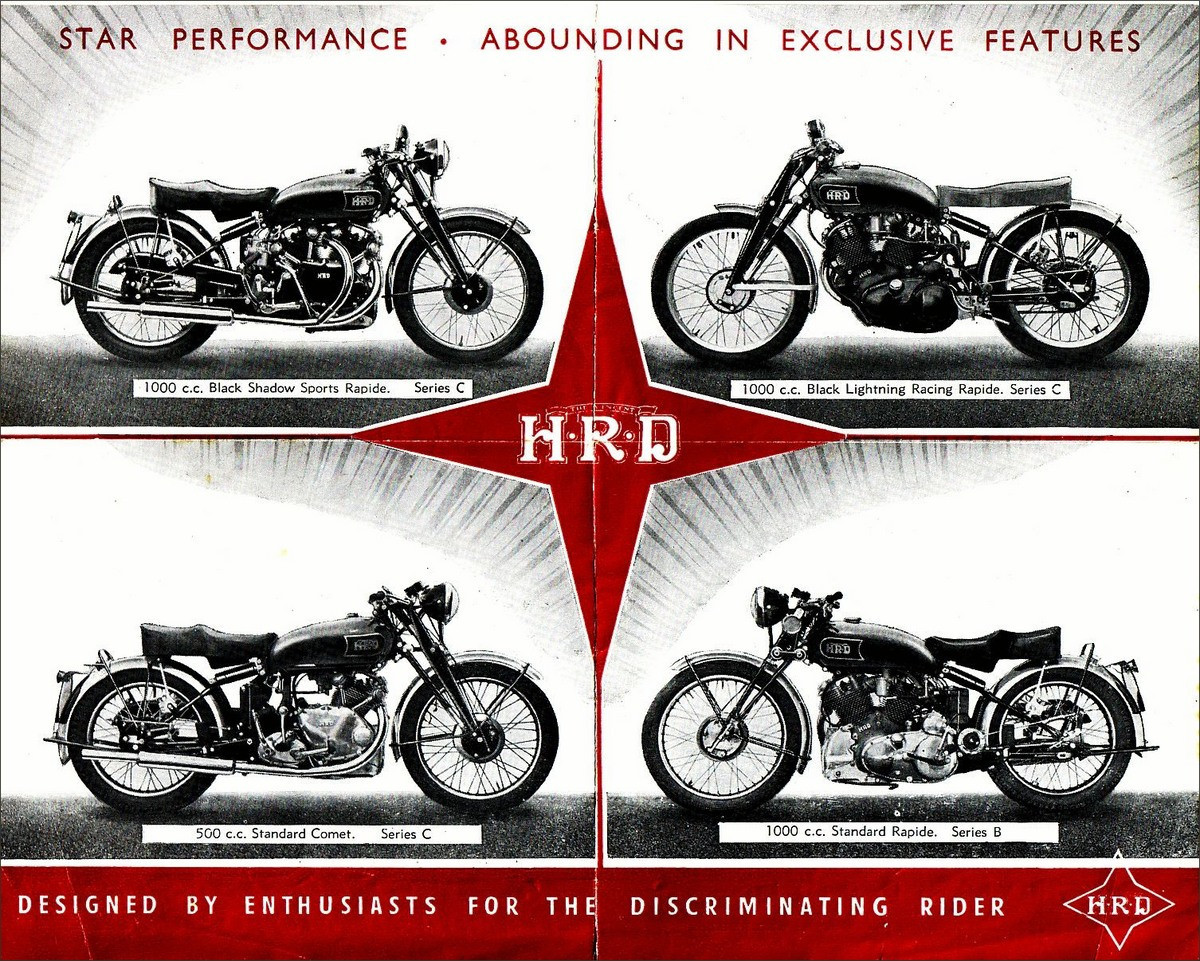

The ultimate Vincent was the Series C Black Lightning, a customer version of the bike on which Rollie Free had broken the AMA’s Land Speed Record in 1948 on the Bonneville Salt Flats, with a similar engine specification. First exhibited at that year’s Earls Court Show in London, and available only to special order, the standard Black Lightning was supplied in racing trim, with rev counter, Elektron magnesium alloy brake plates, special racing tyres on aluminium wheel rims, rearset footrests and controls, a solo seat and aluminium mudguards.

The ultimate Vincent was the Series C Black Lightning, a customer version of the bike on which Rollie Free had broken the AMA’s Land Speed Record…

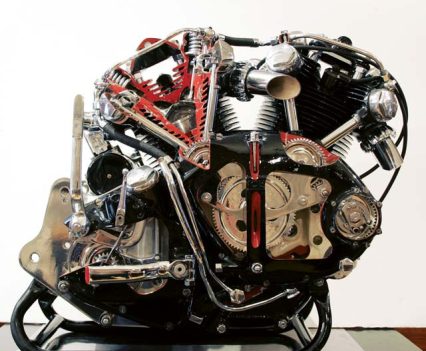

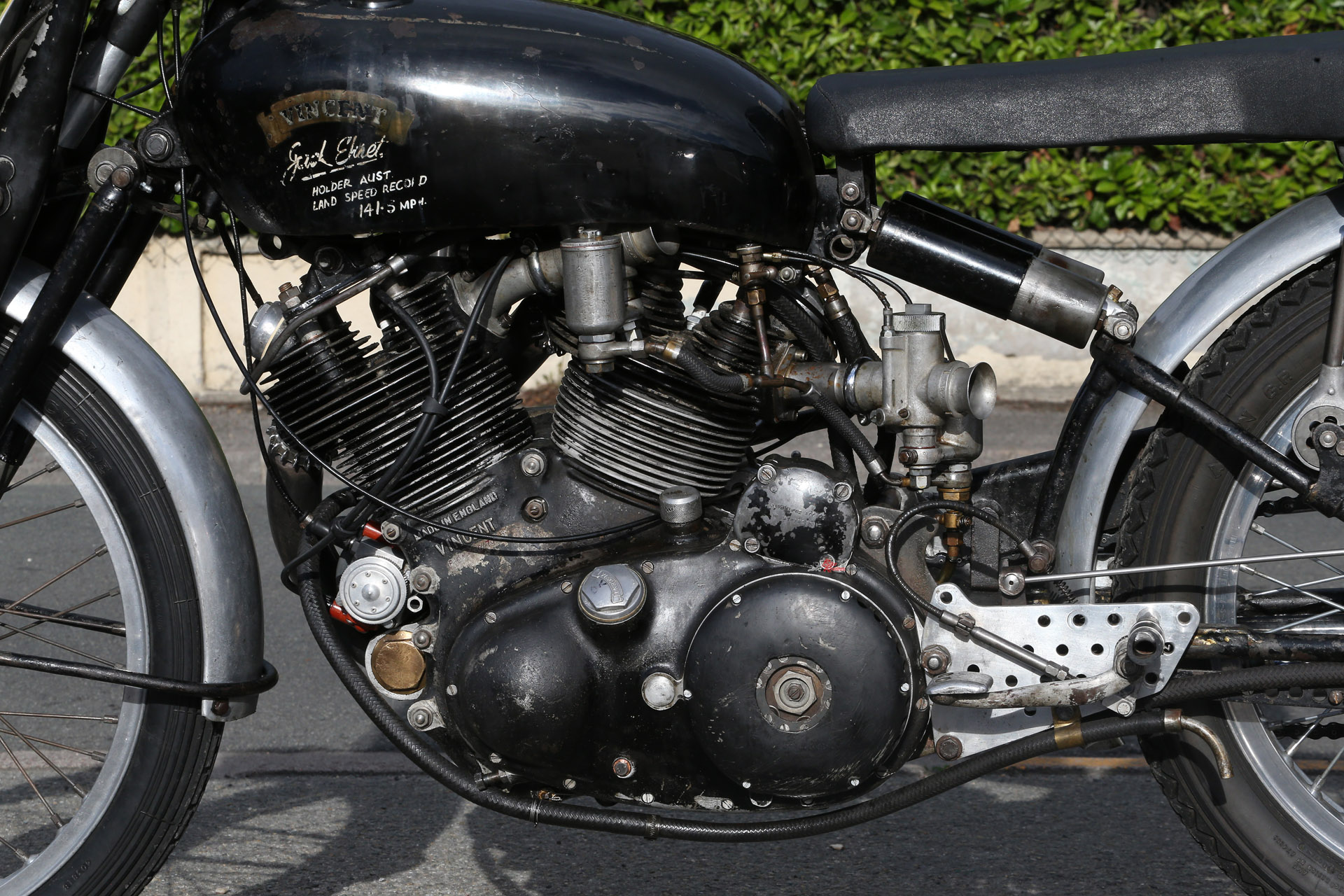

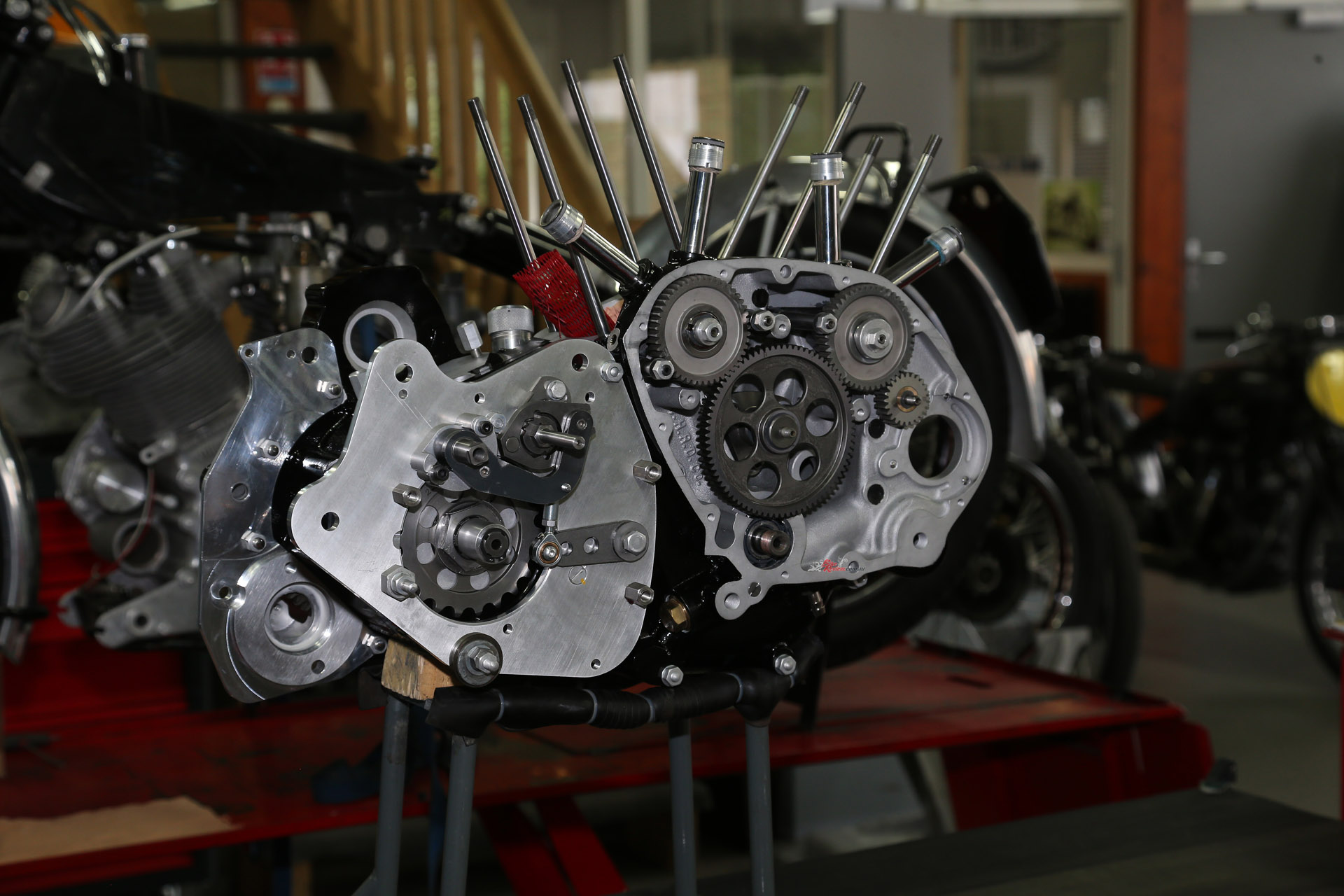

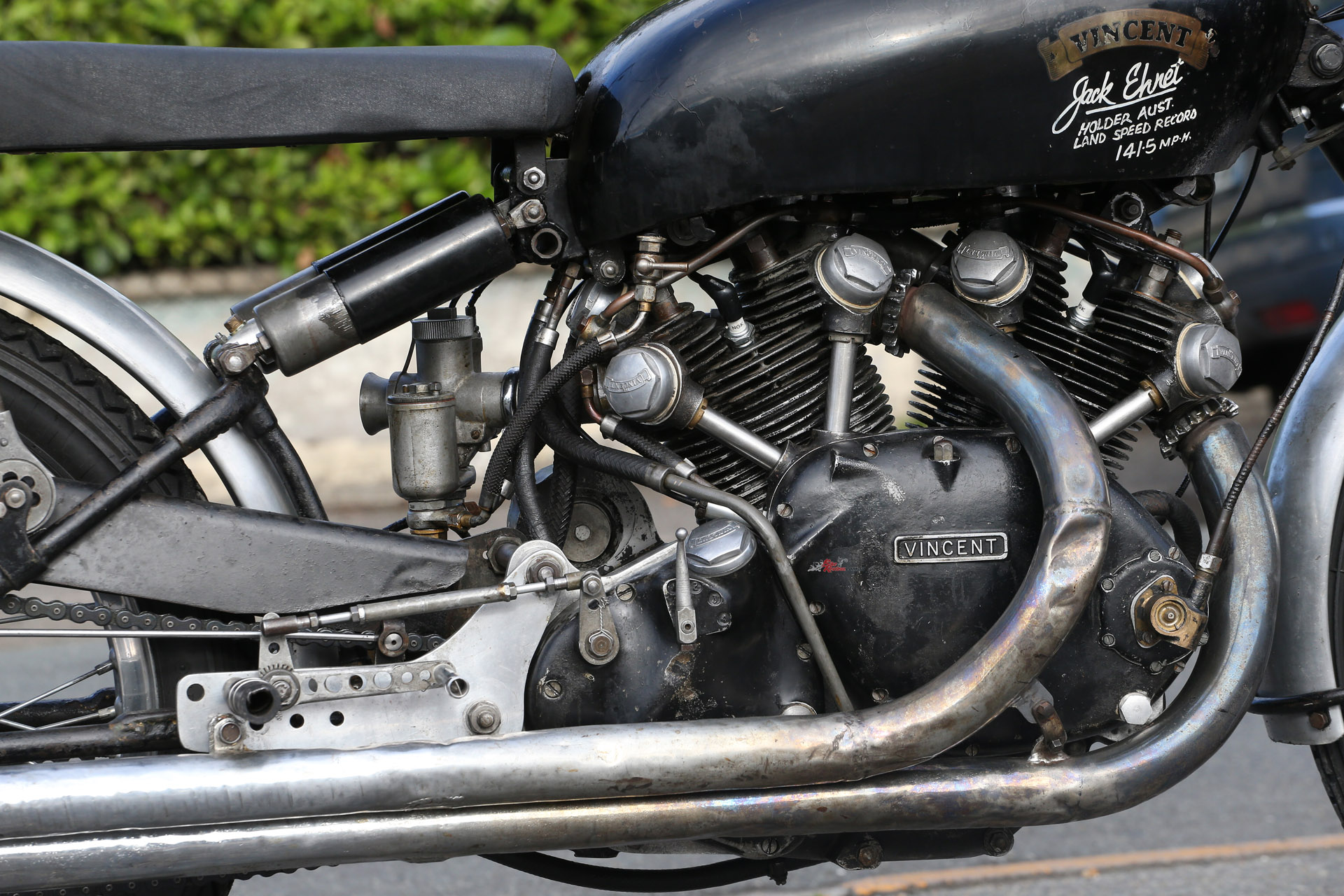

This reduced the stripped-out Black Lightning’s dry weight to 360lb/172kg against the road-going Black Shadow’s 458lb/208kg, complete with lights and a horn. Its 998cc air-cooled high-camshaft dry sump OHV 50° V-twin engine measuring 84 x 90mm and fitted with two valves per cylinder was upgraded with higher-performance racing components, including Mark II Vincent cams with a higher lift and more overlap, stronger highly polished 85-ton Vibrac conrods with a large-diameter caged roller-bearing big end, polished flywheels, and Specialoid pistons delivering a high 13:1 compression for methanol fuel.

“The Black Lightning engine’s spherical combustion chambers were both polished, as were the valve rockers and streamlined larger inlet ports blended to special adapters… and fed by twin 1¼ in/32mm Amal 10TT9 carbs.”

The Black Lightning engine’s spherical combustion chambers were both polished, as were the valve rockers and streamlined larger inlet ports blended to special adapters, and fed by twin 1¼ in/32mm Amal 10TT9 carbs. A manual-advance magnesium-bodied Lucas KVF-TT magneto ran 34º advance as standard ignition timing, with two inch-diameter [51mm] straight-through thin-gauge exhaust pipes. The Ferodo single-plate clutch’s cover featured centre and rear cooling holes, while the four-speed gearbox was beefed-up to transmit the extra power, amounting to at least 70bhp at 5,600rpm (compared to a road-going Black Shadow’s 55bhp at the same revs), and a proven top speed in competition guise of 150 mph, and upwards.

The Black Lightning’s genesis is the stuff of legend for Vincent enthusiasts, which essentially began with London Vincent dealer Jack Surtees, the father of future World champion and Vincent factory apprentice, John. He’d been racing a Norton sidecar outfit with some success, and in 1947 ordered a Rapide from Vincent’s Stevenage factory fitted with some special tuning parts. This engine was built alongside a second such motor, which was then loaned to the firm’s Experimental Tester since 1934, George Brown, who gave the ensuing bike its competition debut at Cadwell Park in Easter 1947. For the Unlimited capacity Hutchinson 100 race at Dunholme later that year, Brown’s special Rapide was further improved, allowing him to finish second in the race to Ted Frend’s works 500cc AJS Porcupine – a bike that would win the inaugural 500GP World Championship in 1949.

However, unlike the AJS, the Vincent could be fitted with silencers for Brown to ride it the 120 miles back to the factory after the race! In this guise, it was tested soon after by journalist Charlie Markham of Motor Cycling magazine, who was ecstatic in his praise for the special Vincent, pinching the title of Rudyard Kipling’s poem Gunga Din to describe it. In this a British Army officer’s life is saved by a lowly Indian water bearer, prompting him to remark, “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din”. Markham’s inference was that the Vincent’s capabilities far exceeded his own, and the nickname stuck, so that Brown’s increasingly successful bike henceforth became known as Gunga Din. Strange, but true…

Read our previous Throwback Thursday articles by Alan Cathcart here…

Gunga Din’s specification was largely adopted on Vincent’s new production Black Shadow – the uprated version of the Rapide that famously needed a special 150mph Smith’s speedo instead of the standard 120mph item. The engine of the new model, at first produced in very limited numbers, was stove-enamelled black, and to assist with publicity, Gunga Din likewise had its motor painted black, with Brown continuing to race the machine to successive British hillclimb, sprint and short circuit victories, including a 1949 win in the Unlimited capacity class at the first motorcycle race meeting to be held on the new Silverstone circuit.

Phillip Vincent then agreed to sell a specially-prepared Black Shadow to wealthy Californian enthusiast John Edgar – the machine to be ridden by Rollie Free at Bonneville Salt Flats in an attempt on the AMA’s Open class Unstreamlined Speed Record, then held by Harley-Davidson. To meet the September 1948 date for the attempt, much midnight oil was burnt at the factory to produce the necessary go-faster bits, and Edgar’s engine was run-in on the test-bed before being installed in a Black Shadow chassis and tested at Gransden airfield. With Brown aboard, it ran easily to 143mph and would have gone faster had the runway been long enough. In Utah, Free, famously clothed in just a pair of swimming trunks and with his legs stuck out behind him, smashed the AMA record on the Vincent, leaving it at 150.313mph (241.905km/h) over the flying mile.

Free, famously clothed in just a pair of swimming trunks and with his legs stuck out behind him, smashed the AMA record on the Vincent, leaving it at 150.313mph (241.905km/h) over the flying mile.

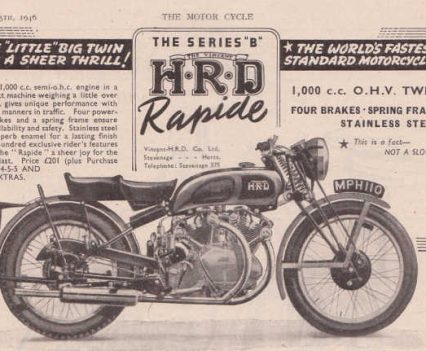

The idea of producing a special racing model based on Free’s record-breaker was a logical progression in what was to be a very big 12 months for the Vincent HRD company. London’s Earls Court Show, which had not been held since 1938 owing to the outbreak of war, was revived in November 1948, to tremendous support from British manufacturers. There, Vincent launched its new Series C V-twin models now fitted with the company’s own Girdraulic fork and hydraulic rear damper, alongside the new, more affordable single-cylinder Comet, and the thrilling Black Lightning production racer, details of which were kept secret until just before the Show – mainly because it was still being built right up to the opening day!

“The completed Black Lightning caused a sensation at Earls Court, despite its enormous £400 price tag (plus a hefty £108 purchase tax) – then sufficient to purchase a nice three-bedroom family house in London.”

The completed Black Lightning caused a sensation at Earls Court, despite its enormous £400 price tag (plus a hefty £108 purchase tax) – then sufficient to purchase a nice three-bedroom family house in London. It’s widely accepted that only 30 complete customer versions – all Series C except for one Series D model – in addition to Rollie Free’s first 1948 Series B prototype were ever built (together with anything up to 13 engines for installation in racing cars, usually with a Cooper chassis), before production ended in 1952 because of Vincent’s financial problems. Deliveries had begun early in 1949, with 15 bikes made that year, followed by seven more in 1950, a further six in 1951, and two more in 1952, the final year of production.

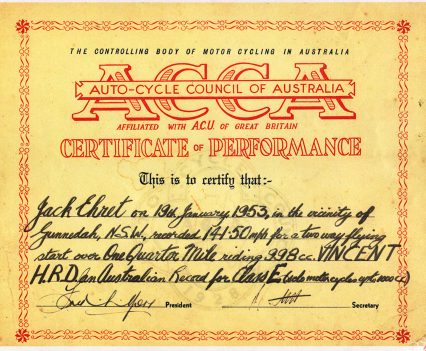

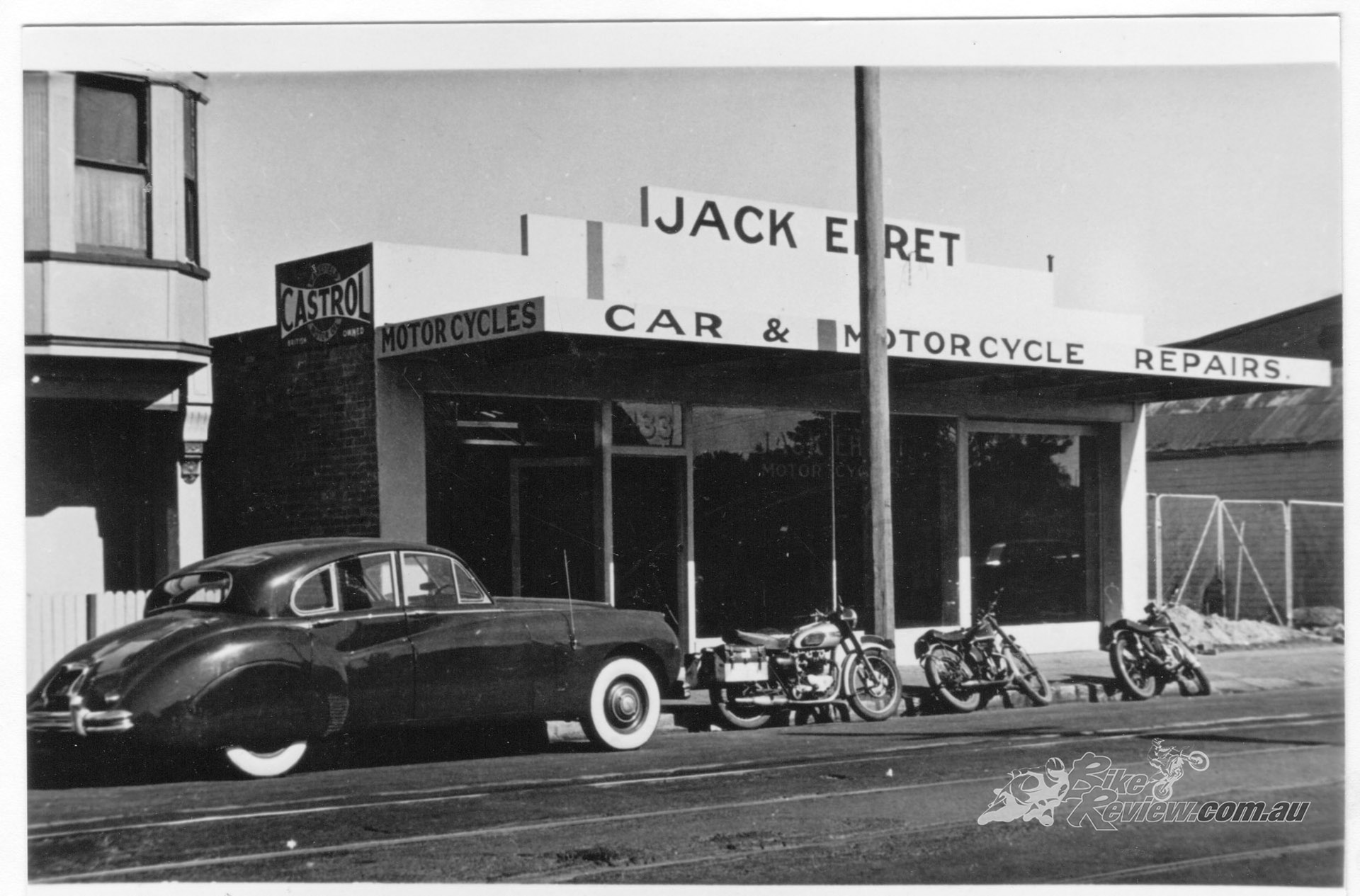

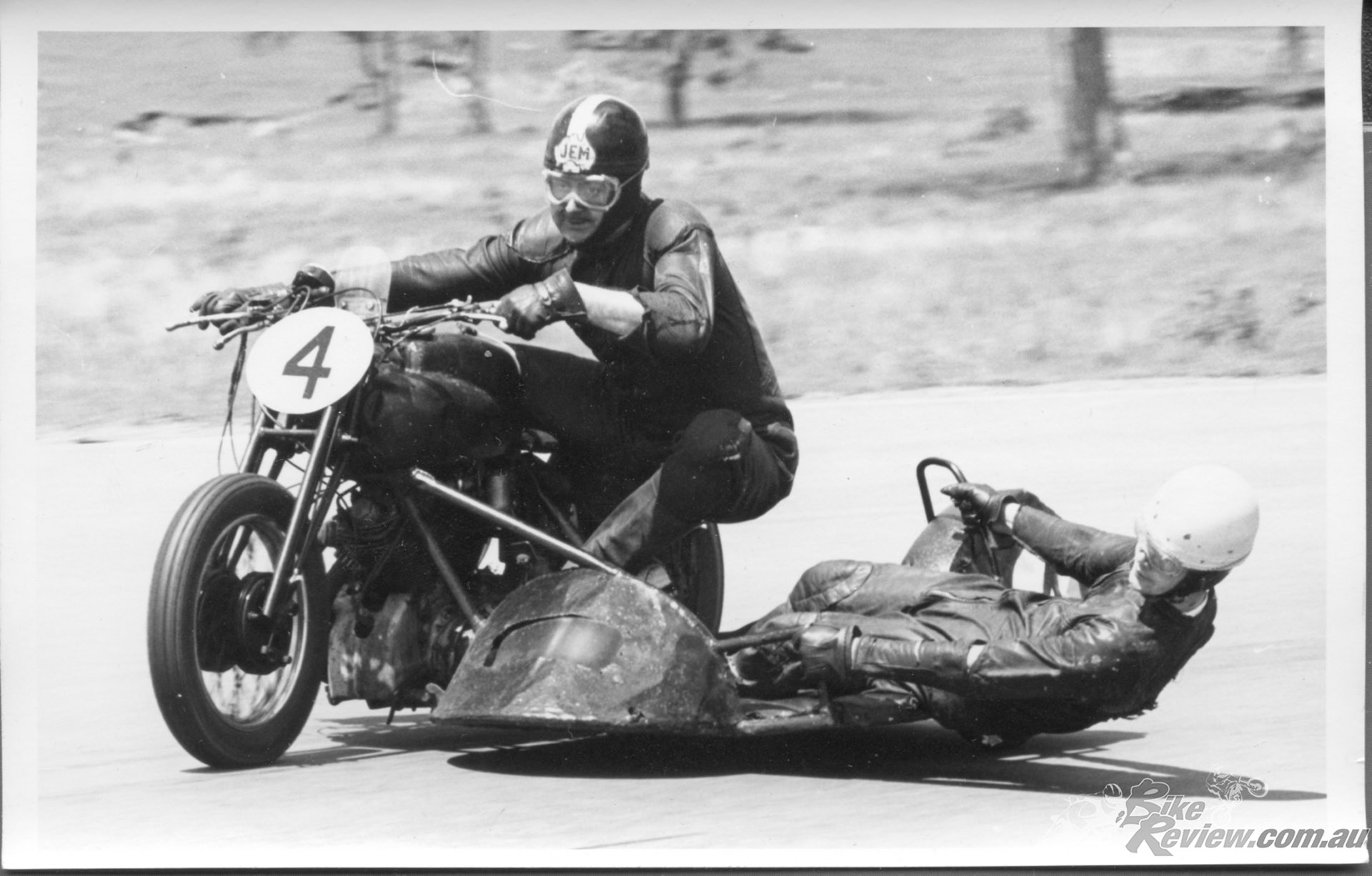

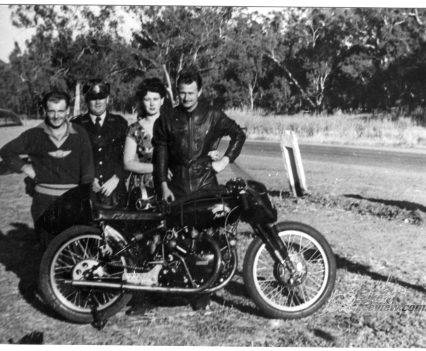

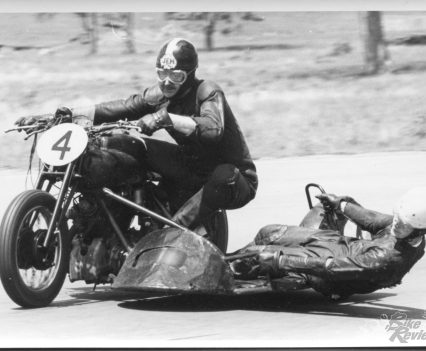

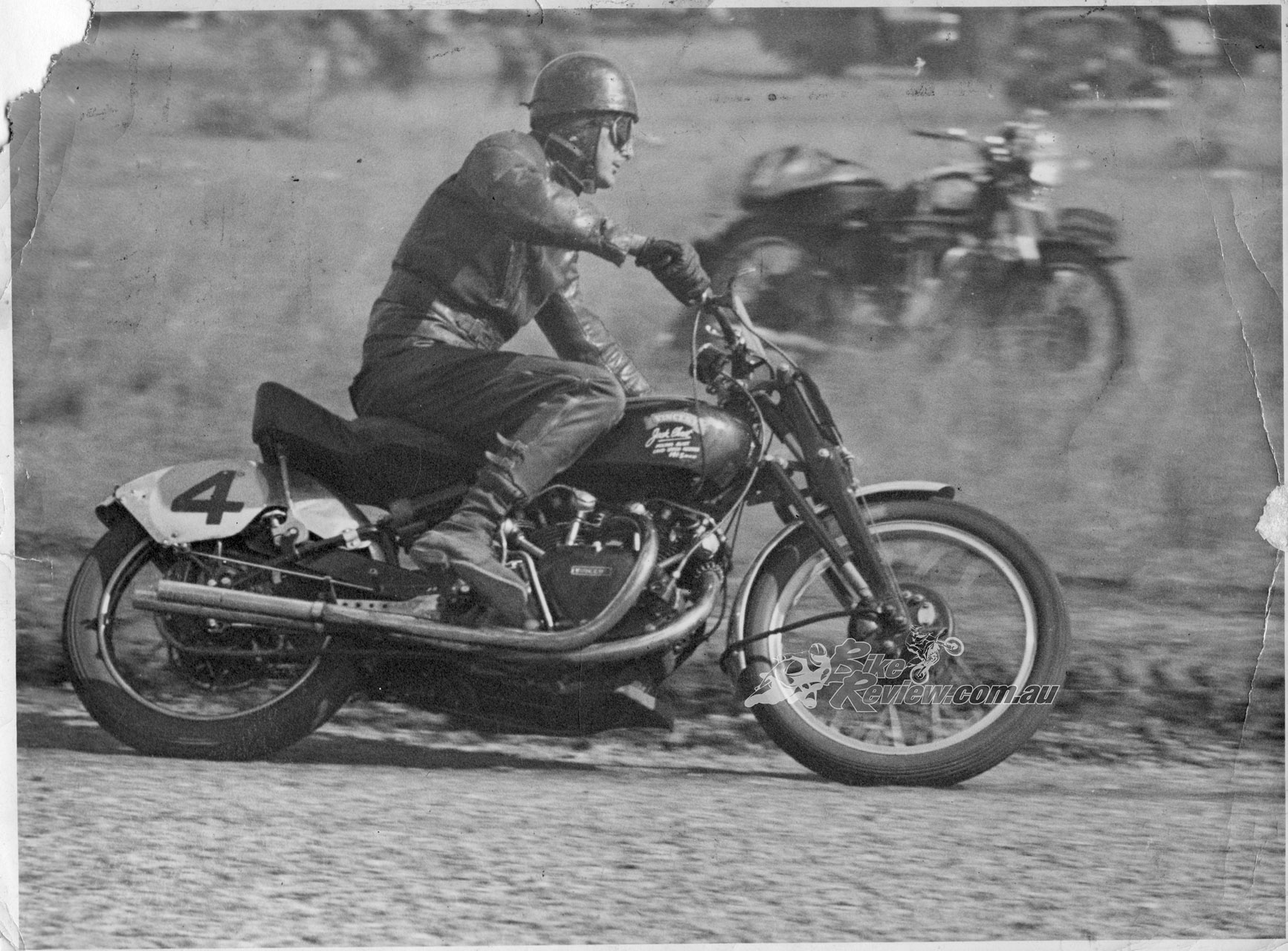

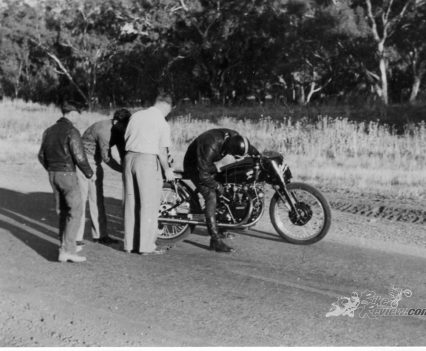

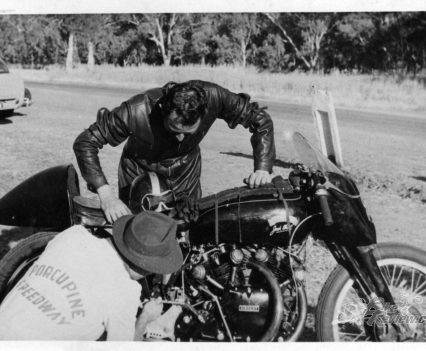

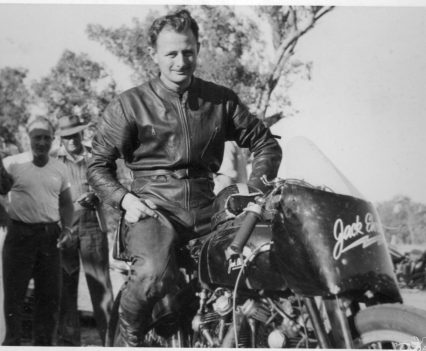

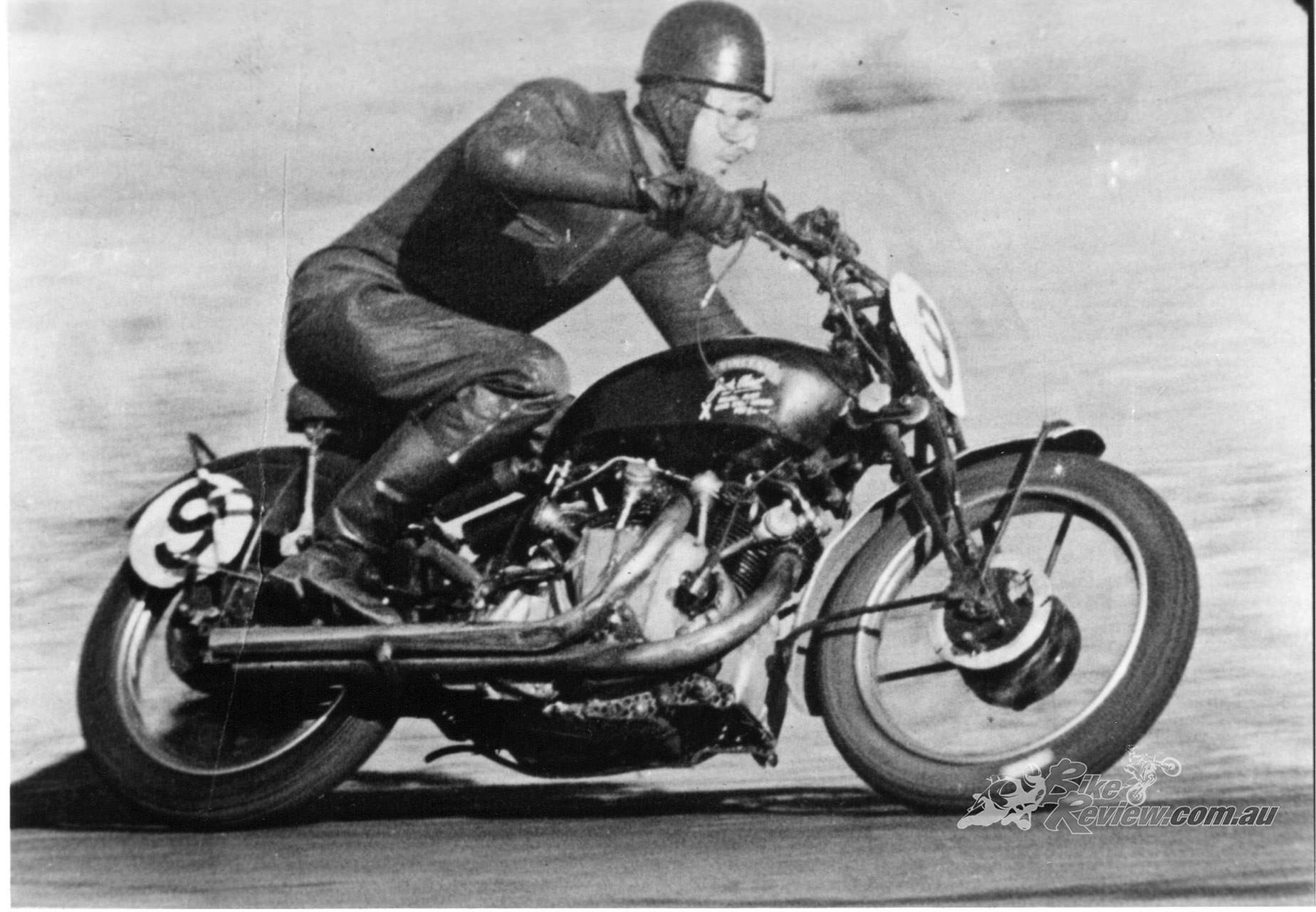

Today, nineteen of these bikes built are believed to still exist, so the astronomical values achieved at auction on the rare occasions when one comes up for sale make the Vincent Black Lightning the most coveted production motorcycle ever made. That status was confirmed by the January 2018 sale at the Bonhams Auction in Las Vegas of the completely original/unrestored ex-Jack Ehret Australian land speed record breaking Black Lightning, which was only retired from competitive racing in 1993, having also won the Australian TT at Bathurst, as well as numerous other races Down Under in its 40-year track career. This bike went under the hammer for USD $929,000 incl. buyer’s premium ($1,429,835 AUD), making it still today the most valuable motorcycle ever sold at a public auction.

This bike went under the hammer for USD $929,000 incl. buyer’s premium ($1,429,835 AUD), making it still today the most valuable motorcycle ever sold at a public auction…

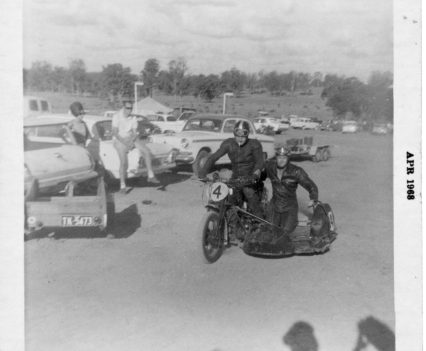

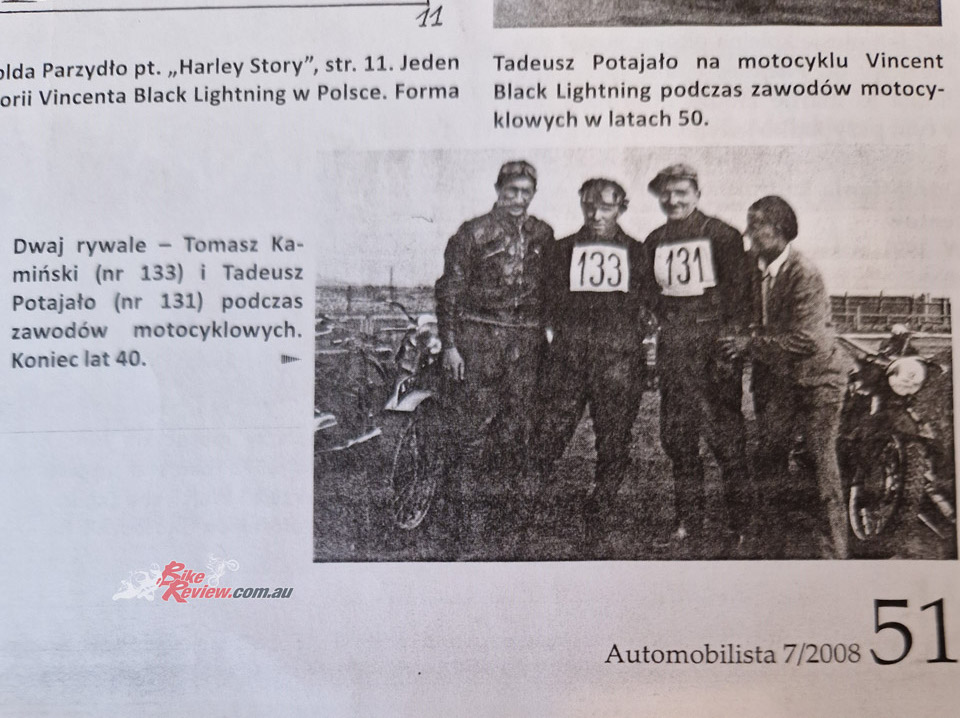

This makes the forthcoming appearance in the Bonhams sale (check out the bike and auction details here) to be staged at the UK’s 2024 Classic MotorCycle Show at Stafford on April 20-21, of one of the so-called ‘Polish Black Lightnings’ particularly significant, albeit as essentially a barn find that has remained in a fortunately dry garden shed ever since 2000, when it was restored for its late owner – who then never rode it, and seemingly rarely even looked at it! This bike carrying engine no. F10AB/1C/3230 in frame no. RC5130C was the 14th Black Lightning to be constructed after the model’s debut in November 1948, and is one of a pair of such bikes despatched to Poland one year later. Factory records show its companion machine was delivered on November 15, 1949, and this its sister bike followed exactly two weeks later, on November 30. Both motorcycles were specifically ordered as being intended for Sidecar racing.

This bike carrying engine no. F10AB/1C/3230 in frame no. RC5130C was the 14th Black Lightning to be constructed after the model’s debut in November 1948…

This was at a time when Poland had sadly once again lost its independence in the aftermath of WW2, becoming a Communist satellite state in the USSR-controlled Eastern Bloc. In such Marxist societies the ruling authorities controlled almost every aspect of their population’s daily life, and as such private citizens were not allowed to import any goods at all from outside the Eastern Bloc for their own consumption – much less complete motorcycles, and especially not such a costly device as a Vincent Black Lightning! Accordingly, the two Vincents were ordered directly from the British factory by a Polish government agency, the CHPM/Centrala Handlowa Przemyslu Motoryzacyjnego Motozbyt (aka Commercial Headquarters of the Automotive Industry’s Motorcycle Division). This meant that both the 13th and this the 14th production Black Lightnings constructed were evidently destined for influential Communist Party insiders who knew how to pull the necessary strings.

The Vincent Works Order Form shows that this machine was delivered without lights or a horn, and besides the standard Lightning spec carried a 280km/h speedometer, straight-through exhausts, racing alloy mudguards, larger 52T and 56T rear sprockets suitable for sidecar use, steel rims, touring footrests, wide ‘bars and sidecar mounting brackets and suspension springs. But both bikes were supplied in solo form, so the sidecars themselves would have been added on in Poland. Vincent factory records show that, upon completion, this Black Lightning was tested by ‘CJW’, believed to be its Works Manager Jack Williams, later to be the creator of the Matchless G50, and father of Peter of Arter Matchless and John Player Norton fame.

“This Black Lightning was tested by ‘CJW’, believed to be its Works Manager Jack Williams, later to be the creator of the Matchless G50”

Without a functioning local motorcycle press back then, and indeed with records of any kind of racing activity in 1950s Poland almost non-existent, it’s only by hearsay that this Black Lightning is supposed to have been raced with considerable success in that country as a Sidecar outfit by one Tomasz Kamiński between 1950 and 1954, when it was taken over by someone named Branecki. It was later acquired and raced by another person called Nowacki, then passed on to someone by the name of Trzcinski, before ending up by 1972 in the hands of a man called Ankiewicz.

Tomasz Kaminski raced this VIncent Black Lightning in Poland with success, it was later raced by other riders.

The other Black Lightning was also apparently raced with a sidecar attached, but neither outfit had any viable competition, so success for their slower competitors was measured by how many times the Vincents lapped them! Eventually, in 1960 the motor from one of the Lightnings was removed and installed in a locally-built streamlined single-seat racing car, the Krab 75. Driven by Longin Bielak and Grzegorz Timoszek, this was speed trapped in a race at Kraków at 196km/h, but after a couple of seasons of car racing the Vincent engine was returned to its parent motorcycle frame.

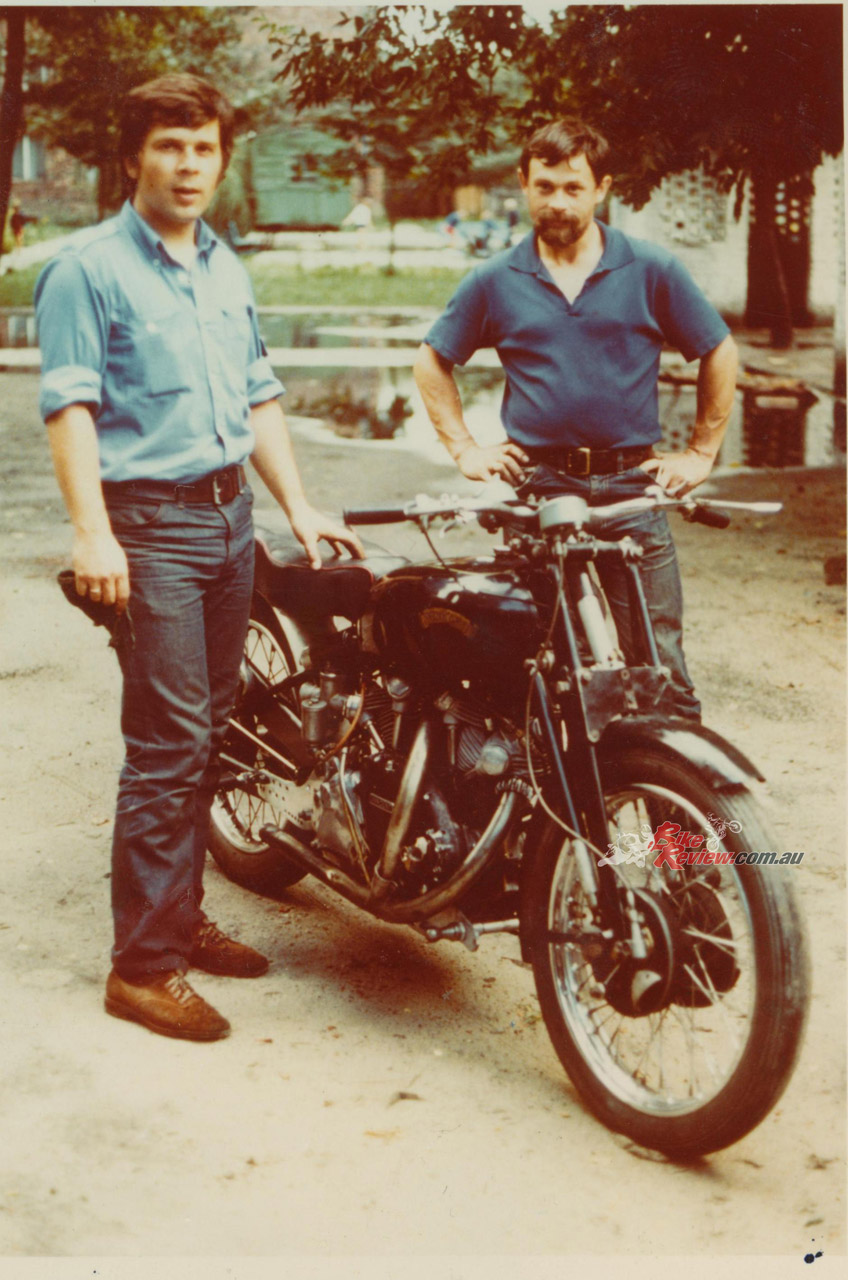

A decade later in 1971, with Poland still very much under Communist rule, British Vincent Owners’ Club member Ian Harper decided to visit the country on his ‘Green Meanie’ Vincent Rapide special. While in Warsaw, Ian met up with two Harley-Davidson riding brothers, Andrzej and Woyciech Echilczuk, who told him that they knew of a Vincent somewhere in the city. This turned out to be one of the two mythical ‘Polish Lightnings’ that Vincent aficionados knew to have ended up the other side of the Iron Curtain, but had given up for lost.

Just over a year later the brothers had tracked down the second such bike, both of which Harper managed to extract from Poland on two separate trips to bring the Black Lightnings back to the UK. Each was dismantled in order to be transported in Harper’s three-cylinder two-stroke DDR/East German-made Wartburg Estate, a choice of car which maybe helped him bring off such a risky enterprise.

Indeed, this bike was classed as ‘scrap’ by the state engineer charged with issuing the needed export paperwork! No.13, the second bike to leave Poland (but the first of the two to be shipped there in 1949) is now in the UK’s National Motorcycle Museum/NMM – but this other version, no.14, has lain undiscovered for the past quarter-century.

For, once back in the UK, Ian Harper did little to the two Polish Lightnings before selling both of them on in 1973 to George Brown’s successor as the Vincent factory’s tester/racer Ted Davis, later its Chief Development Engineer. This motorcycle’s late owner – who must remain anonymous under auction sale protocols – duly acquired this Black Lightning from Ted Davis in 1976, and eventually commissioned marque specialist Bob Culver to restore it, a task completed in 2000. But thereafter, instead of being used or displayed, the Black Lightning was placed under a pile of blankets in a fortunately dry garden shed, where it has remained for the last 24 years. Presented in what Bonhams describes as ‘barn find’ condition, the fully restored time warp machine will require at the very least recommissioning, before returning to the road.

“The Black Lightning was placed under a pile of blankets in a fortunately dry garden shed, where it has remained for the last 24 years… Presented in what Bonhams describes as ‘barn find’ condition, the fully restored time warp machine will require at the very least recommissioning, before returning to the road…”

THE RIDE

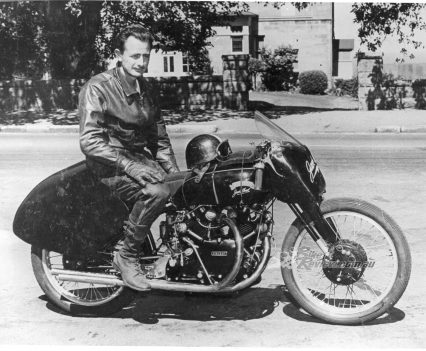

If and when that happens, I’m fortunate to be one of the very few people on Earth to know what the lucky future owner has in store, because back in 2016 I was honoured to be given the chance by its French then owner Nicolas Dourassoff to track test the ex-Jack Ehret 1951 Vincent Black Lightning for two dozen laps of the Carole race circuit on the outskirts of Paris.

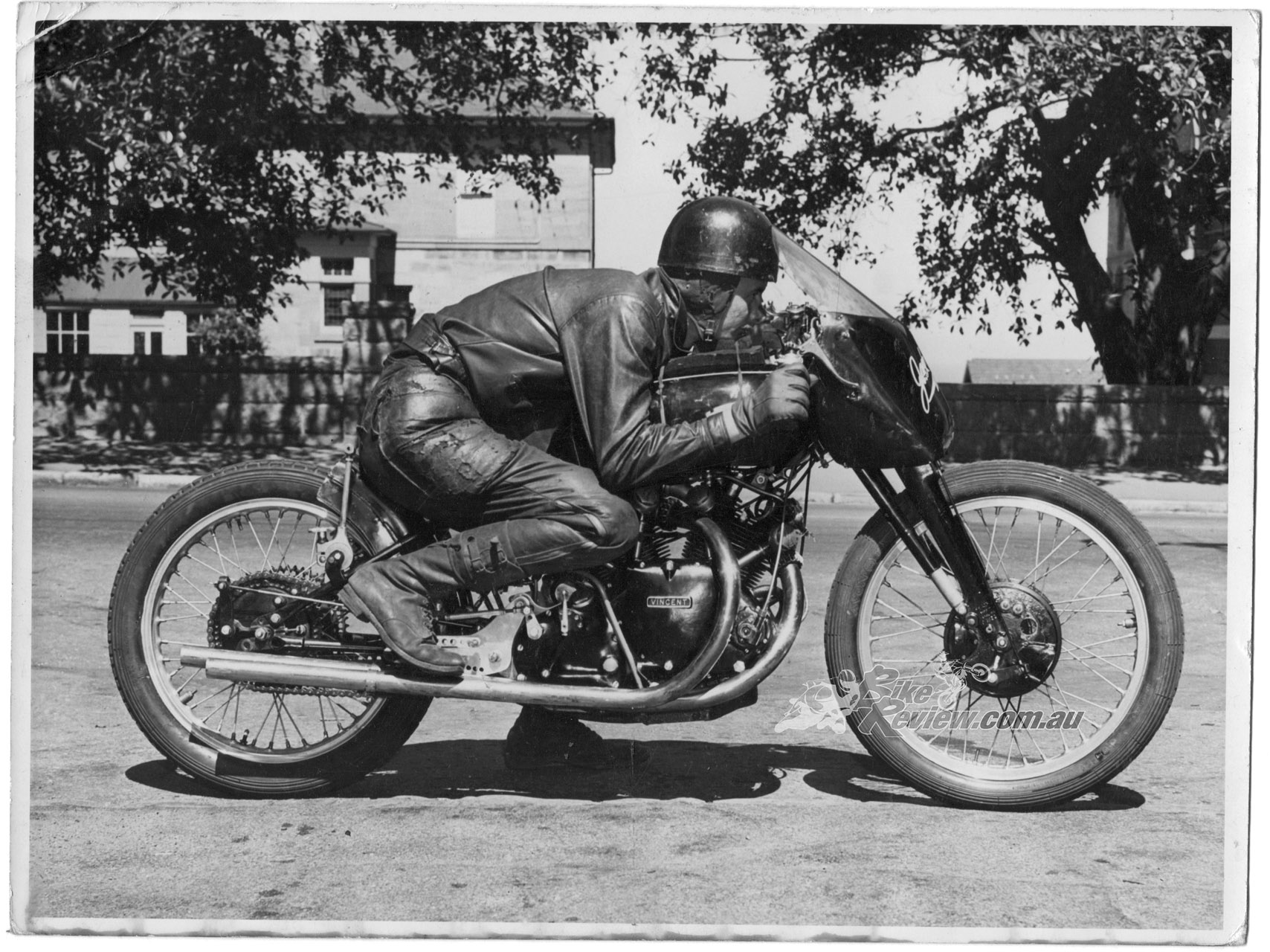

This motorcycle was living history on two wheels, with just 8,682 kilometres from new on its 300km/h Smiths clock, almost every one of them in anger. But the battle-scarred warrior had been recommissioned by the late French Vincent expert Patrick Godet for me to ride on a sunny afternoon Parisian track day.

This motorcycle was living history on two wheels, with just 8,682 kilometres from new on its 300km/h Smiths clock, almost every one of them in anger. But the battle-scarred warrior had been recommissioned by the late French Vincent expert Patrick Godet for me to ride on a sunny afternoon Parisian track day.

However, so that I could properly sample how a Black Lightning should perform without paying due deference to the bike’s age, Godet also brought along a recently built 100 per cent authentic Black Lightning Replica which he’d created for another of his customers, Englishman Peter Fox. Peter had already covered 1200 street miles on it, pronouncing it “huge fun, and incredibly impressive once you get it revving, when it feels like you’re being pulled along by a huge bungee cord!”

Thanks, Peter – I couldn’t put it better myself, for that was indeed the impression I got on the Ehret Vincent once I saw its Smiths Chronometric rev-counter’s needle track its way with traditionally jerkiness to the 3,800rpm mark, whereupon the bungee cord released and I was swept to what must have been unthought-of speed by mid-20th century standards. Nothing much happened below those revs, though, so I had to coax the engine into meaningful action with a dab on the Ferodo clutch’s light-action lever. But from that access point to its inbuilt grunt onwards, the paragon of performance that all this Black Lightning’s records and race victories proclaimed it to be, made itself apparent.

“The paragon of performance that all this Black Lightning’s records and race victories proclaimed it to be, made itself apparent”…

In no time at all the revcounter was showing the 6,000rpm mark, at which point I stabbed the extended gearlever downwards with my right foot to hit a higher ratio of the four available. There were such massive amounts of torque even by today’s standards that the Vincent just lunged forward in the next higher gear when I got back on the throttle again, noting as I did so that its action seemed unaccountably smooth, considering how worn the self-evidently ancient cables sprouting from the right handlebar and leading to the twin Amal 10TT9 carbs, appear to be.

“There were such massive amounts of torque even by today’s standards that the Vincent just lunged forward in the next higher gear”…

That’s because, in recommissioning this retro-racer for track action in accordance with Nicolas Dourassoff’s belief that historic bikes should be seen and heard in action, not stuck in a garage on permanent static display, Patrick Godet had been at pans not to destroy the truth of time. “Once Nicolas decided to preserve the bike in its current state, and not ask me to restore it – which was 1,000 per cent the right decision.

I wanted to make sure that all the new parts I fitted were as least obvious as possible,” he said. “So we stripped the bike totally, and rebuilt it using the original spec parts we’ve manufactured using Vincent’s original Black Lightning drawings that we’ve obtained. We’ve also converted it to running on petrol rather than methanol, since of course we now have much better fuel available today”…

The same thing applied for the original 20-inch rear wheel which had been replaced by a 19-incher, on the grounds that 20-inch racing tyres are no longer available. Now shod with rear Avon GP rubber matched to a front 21-inch ribbed Avon Racing cover, the Ehret Vincent tracked well through Carole’s mickey-mouse infield section, with good grip delivered exiting either of its pair of hairpin bends, which on most racebikes ask for bottom gear.

Not on the Black Lightnings, though, thanks to their huge reserves of torque and the way they broke into a gallop very quickly in second gear once I’d straightened up. I just had to finger the clutch lever lightly to send the surprisingly responsive engine’s revs soaring to the sound of thunder from the straight exhausts, whose stirring hard-edged note denoted heaps of valve overlap.

When that happened I found myself thundering past the R6 Yamahas and 600 Hondas that had out-manoeuvred me in the infield section, only to let them fly past me once again when I anchored up miles earlier for the next hairpin – just as they were probably about to hit top gear! The brakes on the Vincent were easily the worst thing about riding it, and I needed heaps of respect for my braking markers, because basically there was absolutely nothing held in reserve – instead, what never worked very well to begin with got progressively worse, as the pair of tiny seven-inch/178mm single leading-shoe drum brakes fitted at each end (the extra one at the rear for Ehret’s sidecar use) faded massively, and began howling in protest!

Probably no single aspect of two-wheeled engineering has improved so much in the past 75 years as brakes, and for a 150mph motorcycle the Vincent’s stoppers were definitely on the weak side. Plan ahead! The fact that the Black Lightning didn’t stop very well was probably not conceived by the factory as being an issue, inasmuch as this was a motorcycle primarily designed to go fast in a straight line. Still, the Lightning won three Isle of Man TT races, as well as many short circuit events around the world, where presumably its massive engine performance coupled with rear suspension that was streets better than anything else on two wheels back then, more than made up for the braking deficiencies.

Its focus on straight-line performance was also perhaps one reason that the Black Lightning’s gearchange was so awkward, so that thanks to the straight exhausts running under the right footrest, it was very hard to get my foot under the lever for downshifts approaching a turn. Patrick Godet had fitted a sort of extension sleeve to the hollow foot lever which helped a little, but it meant you had to take your foot off the rest to grope around under the lever to hoick it upwards in order to downshift under braking – a necessary assistance to those poor quality stoppers. The problem was probably caused by my modern riding boots being much more robust and protective than the soft, thin ones used Back Then, making the space left by Vincent between the pipes and the footpeg insufficient today.

“Still, I was genuinely impressed how light and precise the steering was, and how much turn speed I could keep up even with the skinny 21-inch front tyre fitted.”

Still, I was genuinely impressed how light and precise the steering was, and how much turn speed I could keep up even with the skinny 21-inch front tyre fitted. “The Lightning is not a bike designed for racetrack use,” said Patrick Godet. “If you want to do road racing you must make an exhaust which goes underneath the engine so you can have a proper gear lever, because with the two straight pipes it is not nice for the rider. If you look at pictures of Black Lightnings being road raced they always had the gear lever raised higher, which was just as bad and is why we extended the lever. I never understood why they did that, since it has so much more performance that you don’t need to change gear very often – it goes in every gear!”

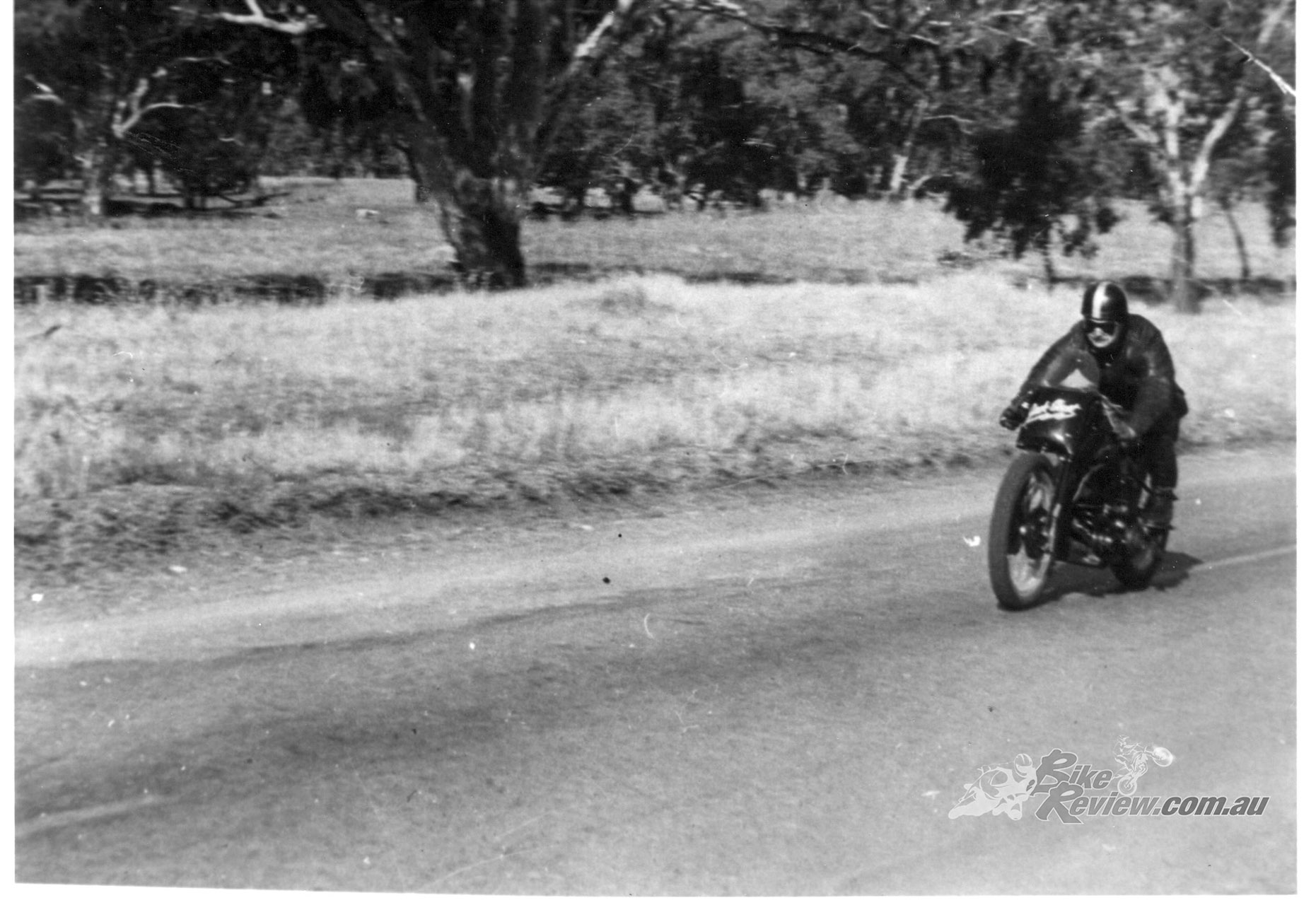

Top: Ehret racing the bike at Bathurst in 1953 and Above: Sir Al on the bike 63-years later in France. Amazing.

I’ll say. Throw a leg over the seat, and you’ll discover at once how low and narrow the Vincent is beneath you – it felt much smaller than a 150mph bike of the Fab Fifties had any right to. The one-piece handlebar was quite narrow and flat, but with upturned ends which delivered a comfortable leaned-forward mile-eating stance, while still giving good leverage in the tight turns that proliferated at Carole. The Vincent’s low-speed handling was rather ponderous, though, with the distinctive Girdraulic wishbone forks’ pressed-aluminium girder blades describing a lazy arc as you leant into a turn, feeling all the while they were about to fold in on themselves.

“The one-piece handlebar was quite narrow and flat, but with upturned ends which delivered a comfortable leaned-forward mile-eating stance”

But this never happened, of course, and instead the handling became more assured as I upped the pace, with greater precision in steering than the relatively primitive telescopic forks of the day. No wonder John Britten and Claude Fior, two farsighted modern day technical gurus who are both sadly no longer with us, developed alternative versions of the Vincent blade forks three decades later for their exercises in alternative two-wheeled thought. By the standards of the day the Vincent’s ride quality was excellent, too, the cantilever rear suspension with a single hydraulic damper and twin spring boxes under the saddle eating up the few bumps on the Carole circuit.

But it’s that torquey, great-sounding 70bhp V-twin engine that’s the real star of the show in the Black Lightning. It made every one of those horses count in delivering a level of performance that, while more than satisfactory today, must have been truly mind-blowing by the standards of Back Then. Acceleration was forceful above the 3,800rpm power threshold, and with the crack of the straight-through exhausts echoing in your ear, it was a real thrill to wind open the light-action throttle and feel the wind on your helmet intensify as the needle cranked round that speedo parked in front of the revcounter. 75 years ago Phil Irving’s masterpiece motor delivered a level of performance nothing else could live with.

This Vincent Black Lightning was not just an ultra-desirable collector’s item, but provided an entirely faithful window on the refined but still raw-edged level of performance which Philip Vincent’s motorcycles delivered over seven decades ago. To be invited to ride such a historic and unrestored such bike, which was almost certainly the last 100 per cent original example of the most desirable series production model ever made, by any manufacturer, was an act of generosity on the part of its then curator (as he described himself) Nicolas Dourassoff. Let’s hope that the ‘Polish Lightning’s’ new owner will ride and enjoy it, too – as sadly its late owner never did – rather than locking it up indoors as the mechanical objet d’art it undoubtedly is.

THE ORIGINAL SUPERBIKE

Founded in 1928 by ex-Harrow public schoolboy and Cambridge University graduate Philip Vincent, when he purchased the defunct HRD company with the financial aid of his father, an Argentinian cattle rancher, the Vincent marque lays valid claim to having produced the first true Superbike in motorcycling history. The series of 998cc V-twins produced over the two decades from 1936 (with a five-year gap during WW2, when Vincent HRD production was devoted to non-biking war materials) set new standards for two-wheeled performance and engineering excellence, which no other motorcycle manufacturer in the world could match.

This was reflected in the endless succession of race victories and speed records obtained by Vincent riders between 1946 and December 1955, when production ceased. These included Rollie Free’s 1948 World Land Speed Record for unsupercharged motorcycles at 150.313 mph, beating Harley-Davidson’s record at Bonneville wearing only a pair of swimming trunks and lying prone on his stomach aboard his Vincent with his legs stuck out the back, all to reduce drag. Ironically, Free’s success also helped to seal the fate of the old HRD brand name. To avoid confusion with Harley-Davidson, which was usually abbreviated to H-D, in the USA – soon to become Vincent’s largest export market with 1,072 bikes sold there, some way ahead of second largest Australia with exactly 600 – the motorcycles became known just as Vincents, although for some time HRD was still displayed on the crankcases due to the stockpile of parts.

Created in 1936 by the brilliant Australian engineer Phil Irving, only 78 versions of the first Vincent HRD Series A high-cam 47° V-twin were in fact manufactured before the outbreak of war but, redesigned by Irving for the postwar era, its revamped 50° V-twin successor the Series B Vincent was released in standard Rapide form in 1946, comfortably living up to its claim to be the fastest and safest production motorcycle in the world. In high-performance Black Shadow form, and especially in competition Black Lightning guise, the Vincent earned an enviable global reputation as the leading-edge benchmark of motorcycling excellence.

Progressively improved in Series C form from 1949, and Series D (1954), a total of 6,852 examples of the Vincent V-twin were produced after 1946 – some in fully-enclosed Black Prince and Black Knight sports touring guise – before the company shut down in 1955 after manufacturing just 11,036 customer motorcycles in total, including 4,184 versions of the Comet single. Despite introducing a host of avantgarde technical features still found on today’s motorcycles – such as cantilever rear suspension, aluminium blade forks with hydraulic suspension, and monocoque frame construction using the high-cam unit construction engine as a fully-stressed member, suspended from a central oil tank – Vincent’s insistence on an uncompromising quality of manufacture and engineering was sadly incompatible with also making a profit. But the calibre of his company’s products was underlined by the success they continued to enjoy in open-class competition well into the 1970s, and their prized status as collectable – and usable – period pieces today. Over seventy years ago the Vincent set standards for others to aim at. Truly, it was the world’s first Superbike.

VINCENT SERIES C 1951 BLACK LIGHTNING SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: Air-cooled dry sump OHV 50-degree high-cam V-twin four-stroke with two valves per cylinder, 84 x 90mm bore x stroke, 998cc, 70hp@5600rpm, 13:1 compression ratio, 2 x 32mm Amal 10TT9 carburettors with remote float chambers, Lucas KVF-TT magnesium body magneto ignition with 34º advance, four-speed gearbox with chain primary drive, Ferodo single plate dry clutch.

Chassis: Fabricated steel monocoque chassis incorporating the oil tank, with engine as fully stressed member, Vincent Girdraulic tapered oval-section forged-aluminium girder fork (F) with Vincent hydraulic shock, Cantilever steel swingarm with single Vincent hydraulic shock and twin separate springs (r). Single leading shoe drum brake (178mm) front and rear, 3.00 x 21in wire laced Dunlop alloy rim with Avon Racing tyre (f), 3.50 x 19in as tested Morad alloy rim with Avon Racing tyre (r).

Performance: Top speed 142mph (228km/h)