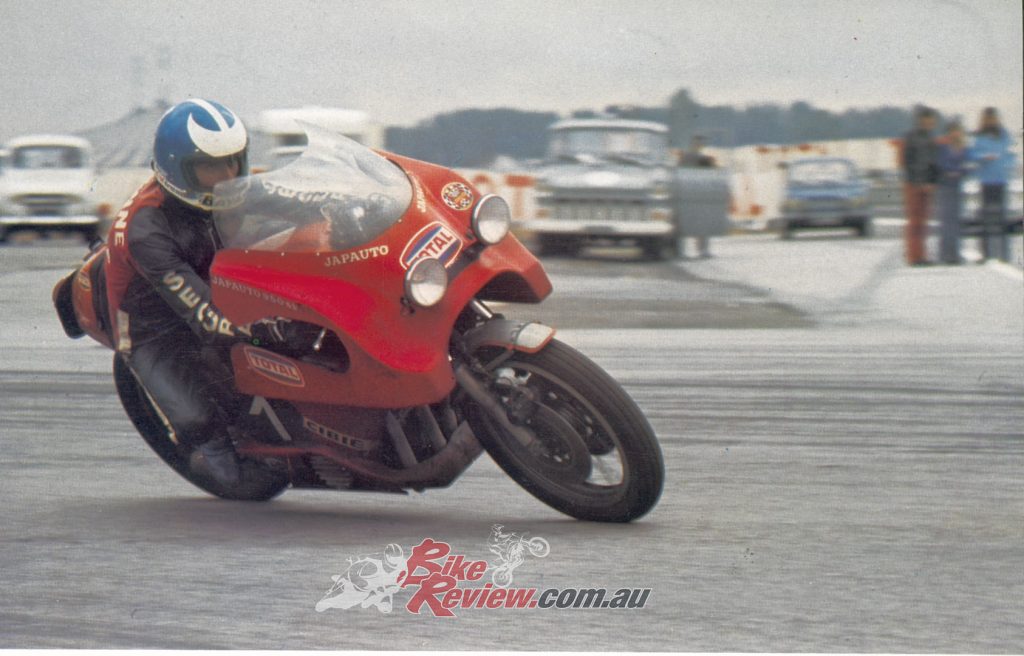

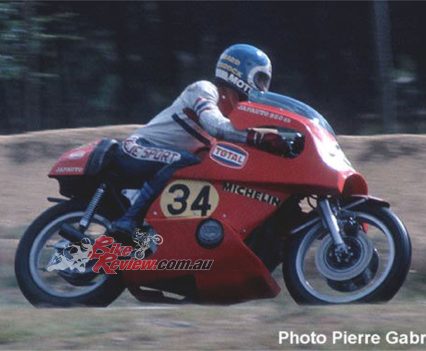

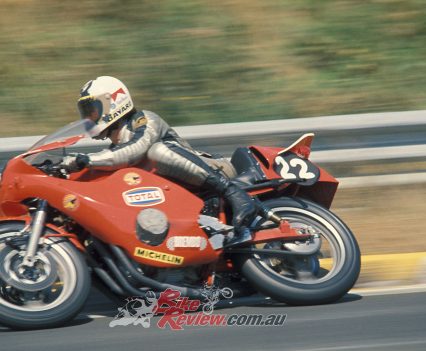

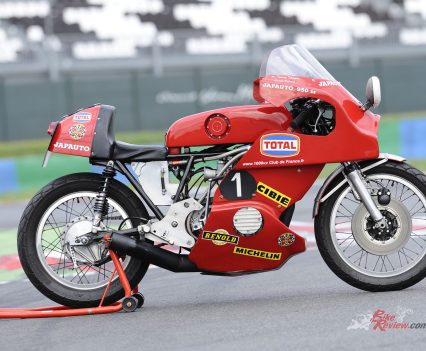

Alan Cathcart rides this amazing 1973 Japauto 950SS replica of the bike that won multiple Bol d'Or 24hr races for then Europe's largest Honda dealership. The test is a special one, with a huge history piece included... Photography: AC Archives, Fabrice Berry

Japauto went from zero to hero with essentially overnight as the Honda CB750 broke cover in France back in the 60s. Avid racing fan and excellent business man Christian Vilaséca had the 950SS built and ended up with taking home the prestigious Bol d’Or multiple times…

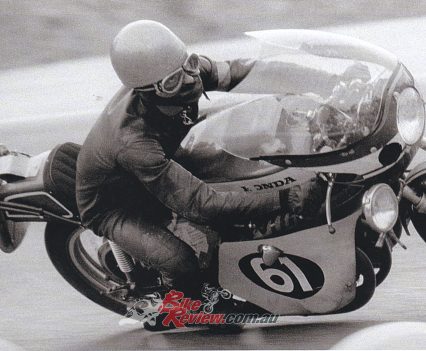

The CB750 marked the turning point for Honda on the world stage. Alan rode a replica of the amazing multiple Bol d’Or winning Japauto 950SS.

Head here to read the full history of Japauto…

We all have landmark moments in our lifetimes, whether tragic – like recalling where you were when you heard about 9/11, or Elvis Presley’s death – or simply memorable, like watching Mike Hailwood win his comeback race in the Isle of Man TT, or Colin Edwards fending off the two works Ducatis of Troy Bayliss and Rubén Xaus on his Honda V-twin, to clinch the World Superbike title at Imola in what many agree was the most exciting road race ever held.

We all have landmark moments in our lifetimes, whether tragic – like recalling where you were when you heard about 9/11, or Elvis Presley’s death… In my own case, right up there with either of those was the day I saw a Honda CB750 for the first time.

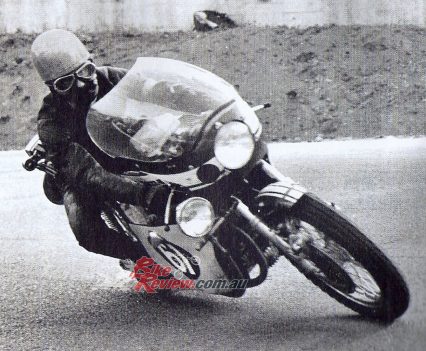

In my own case, right up there with either of those was the day I saw a Honda CB750 for the first time in the metal, in the summer of 1969. I was living in Paris, working in an office on one of the avenues leading off the Place de l’Etoile, a spoke in the hub housing the Arc de Triomphe. I’d often make a dogleg walking home from work to drop in on the largest Honda dealer in Paris – in the whole of Europe, I learnt later – in the adjacent Avenue de la Grande Armée, and I remember only too well seeing the future of motorcycling for the first time that summer sitting there on a plinth, a red and gold symphony in metal with four – count them! – chromed exhaust pipes, and the first disc brake I ever saw on a bike. The world had changed.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

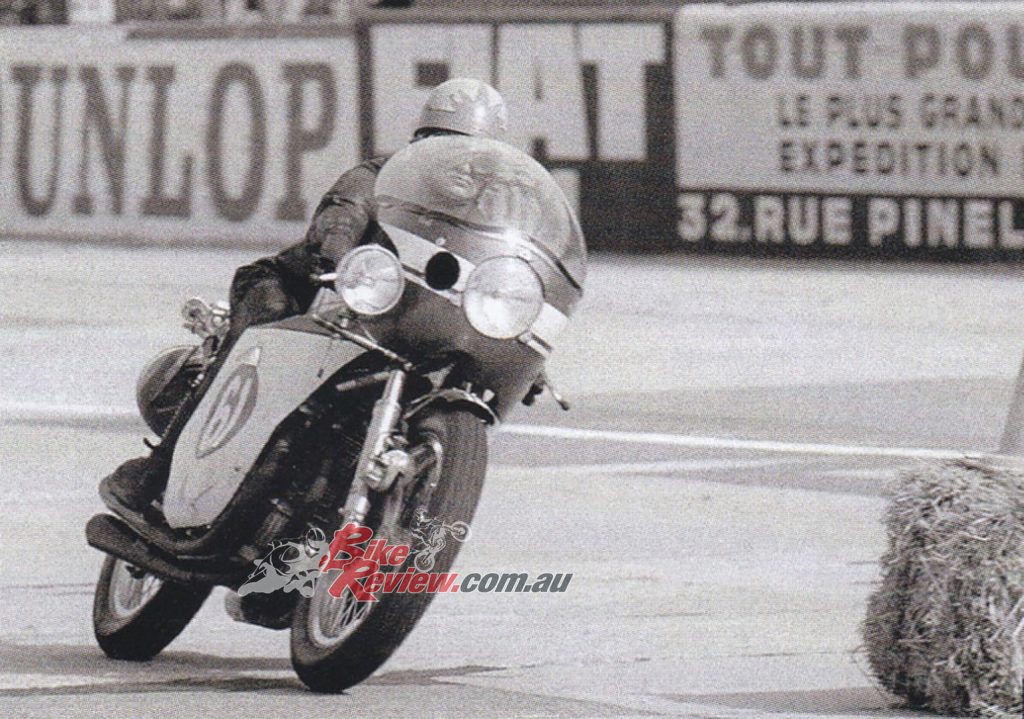

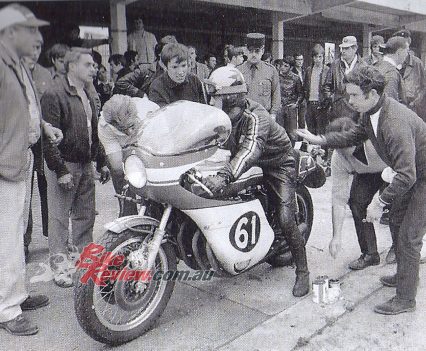

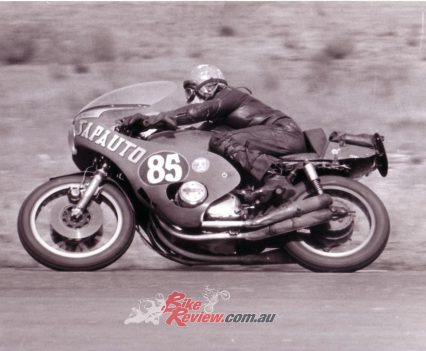

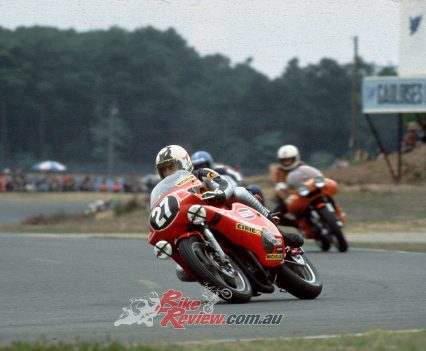

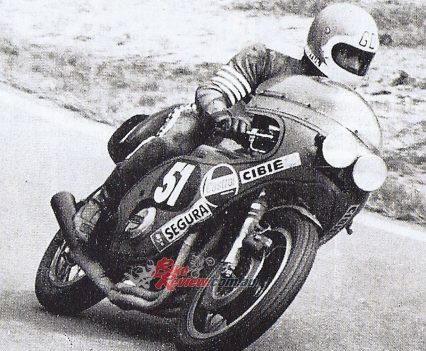

That dealer was named Japauto, and I remember that later on one of my increasingly more frequent visits to ogle the new Honda – yes, they eventually let me sit on it! – I found a begrimed CB750 road racer with twin front discs (count them, too!) and red-and-white fairing taking its turn on the plinth, complete with a large trophy next to it and an advertising banner announcing that this Japauto Honda had won the Bol d’Or 24 Hour race at Montlhéry the weekend before.

I was mortified I hadn’t known the race was taking place – I obviously wasn’t reading the right magazines, since it was thanks to Moto Revue it had been revived after an eight-year intermission! – but the bike’s victory removed any last concern that this four-cylinder Japanese engineering jewel might lack reliability, let alone performance. Which, of course, was exactly why Sonauto patron Christian Vilaséca went racing in the first place….

I’d started saving up to buy my own CB750 from Japauto, but then I left France that winter to go to work in South Africa, so that never happened. But I had the sense to subscribe to Moto Revue (I still have the copies in my library!), which is how I kept track of the Japauto story, including the development of the 950SS the firm scored two more Bol d’Or victories with, and then the creation of the VX1000 streetbike, complete with bright red wacky-racer bodywork which stood out a mile away – nothing else looked like a Japauto back then, and that’s still the case today.

So the chance to finally get to ride one of these iconic French motorcycles at Magny-Cours as a post-race digestif to the annual Bol d’Or Classic was not only very appropriate, but also represented mission accomplished for me personally. For forty years I’ve been wondering what a Japauto was like to ride, and now thanks to Patrick Massé, whose first bike at the age of 20 was a Japauto-supplied CB750.

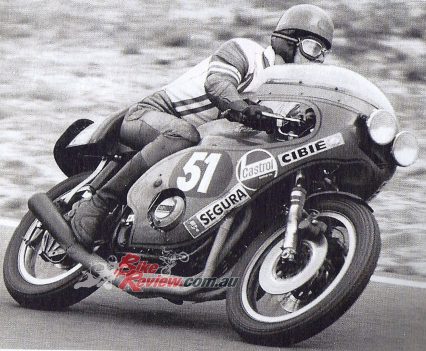

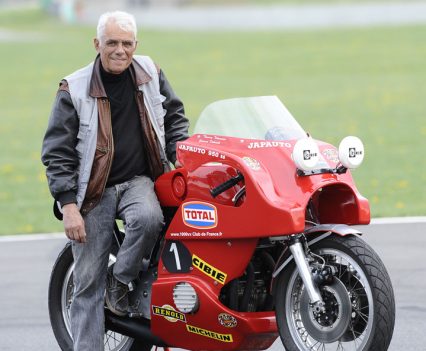

Patrick and his wife Véronique are the founders of the 1000VX Club de France, the Japauto owners/enthusiasts club (check it out here, you’ll need to know French), and as passionate supporters of the Parisian marque they each ride an original example of one of its models, amongst the various bikes consisting of aftermarket frames wrapped around the CB750 motor that’s the theme of the Massé collection. Egli, Dresda, Seeley, Rickman, Moto Martin, Segoni, Japauto, PEM, they’re all there – except a German Eckert and a Bimota HB1, if you know of any for sale!

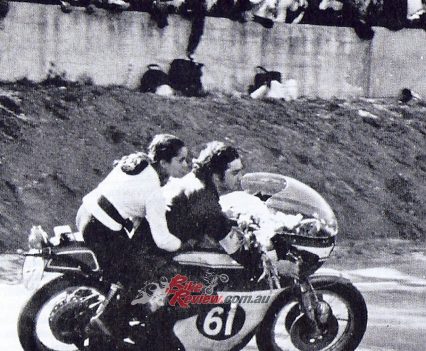

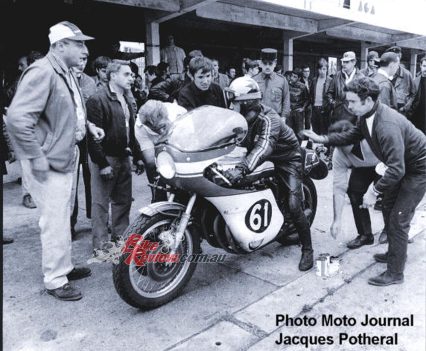

Patrick Massé, seen here with Thierry Tchrnine, and his wife Véronique are the founders of the 1000VX Club de France, the Japauto owners/enthusiasts club.

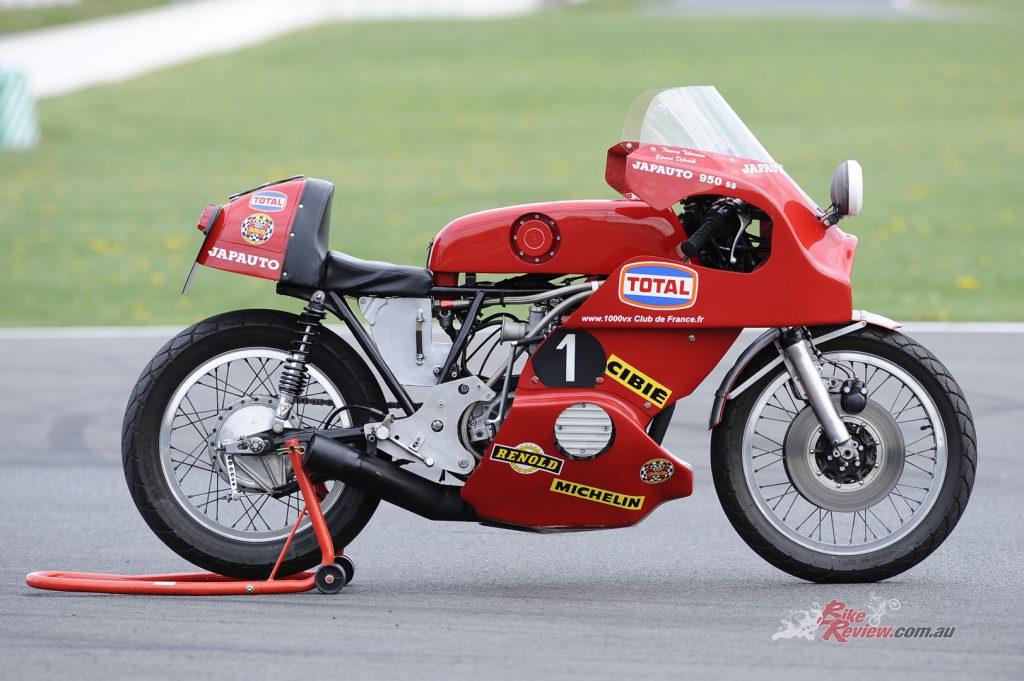

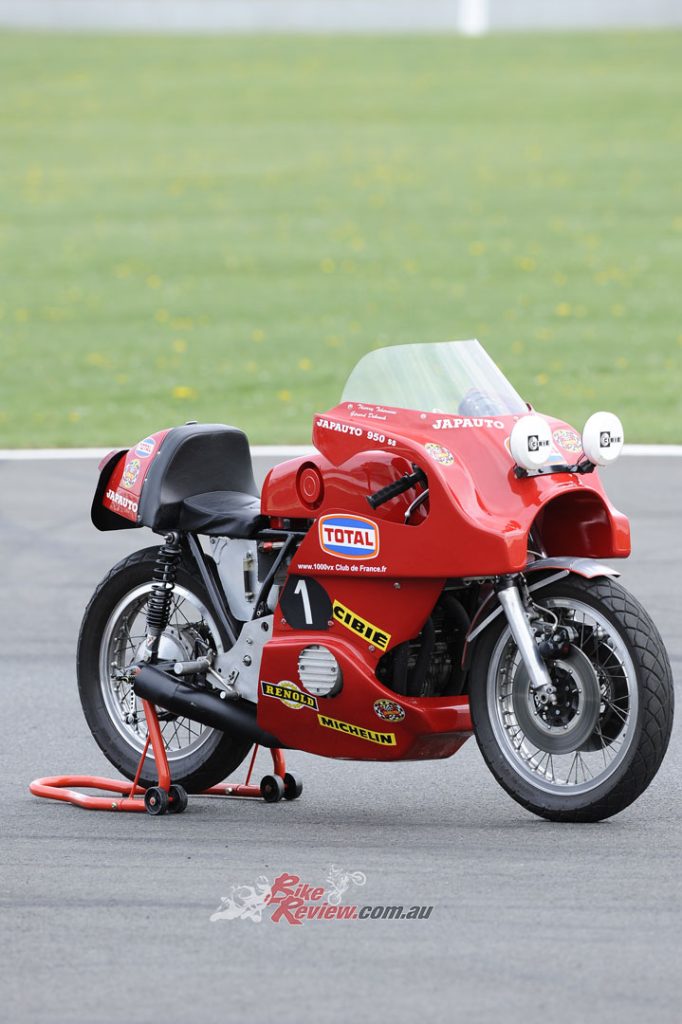

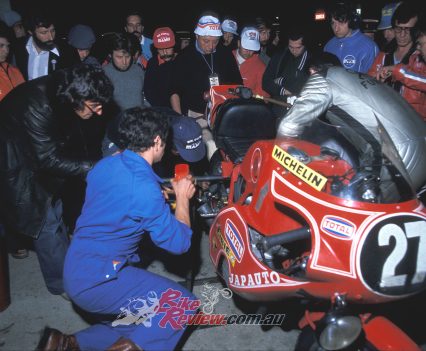

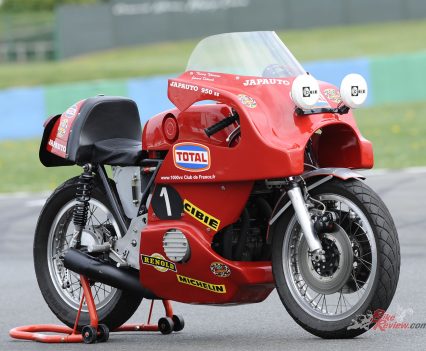

But Japauto is the one the Massés have a soft spot for, and they’ve also built up a stock of original Japauto parts – so when it came to constructing a replica of the victorious 1973 Bol d’Or-winning bike in 1999 for riders Gérard Debrock and Thierry Tchernine to demonstrate at the Coupes Moto Legende to mark the 30th anniversary of the revival of that race, Patrick was able to delve into his storeroom and come up with all the key original Japauto parts to turn a stock ’74 CB750K2 into a lookalike ‘73 Bol d’Or winner in the space of just two months, with the help of his friend Gunther. But, where’s the original race-winning bike?

“If it existed today, I wouldn’t have done this – but very few of the Japauto team bikes have survived, and those that have are mostly incomplete,” says Patrick with a grimace. “It’s strange, for someone who understood the value of racing as a publicity tool, but Christian Vilaséca never kept any one year’s Endurance racer complete, not even the race-winning bikes. They’d get stripped down for parts for next year’s racers, or else be modified to improve performance. He wasn’t interested in the past, only the future.” How very Japanese.

As the 950SS was a marketing tool, it was strange that Christian didn’t keep any around. But as Patrick said, he was only interested in the future not the past.

So the bike waiting for me in the pit lane at Magny-Cours as the prizegiving for the 2009 Bol d’Or Classic came to an end, was a faithful replica of the 1973 race-winner, as no less a person than the late Thierry Tchernine confirmed as he gave me some tips on how to ride the bike, Thierry, who sadly passed away the following year, had ridden the replica on a couple of occasions, and confirmed its authenticity.

“Riding this bike peeled back the years for me,” he enthused. ”It’s hard to believe it’s not the same one we raced back then – especially the engine, which is so flexible and forgiving, just like that one was. You’d never use bottom gear on the track, even in a tight hairpin, because the big engine had so much torque you could pull out of there in second. It was an ideal Endurance racer – it wasn’t demanding to ride hard, so even when you were tired, you could still go fast on it.”

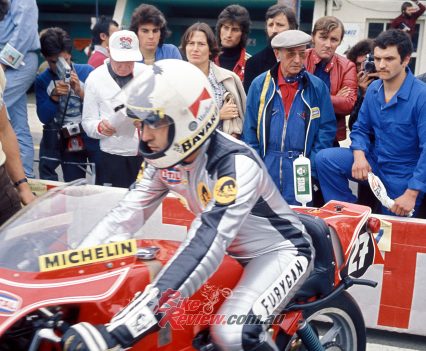

“You have to stand on tiptoes to throw a leg over the Japauto, on account of the tall seat back containing the battery.”

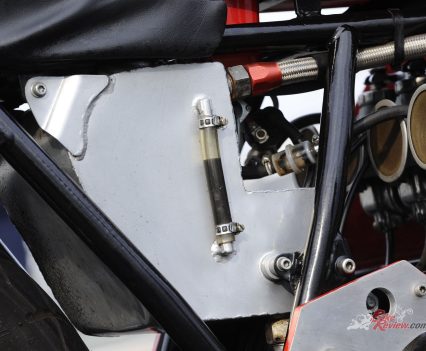

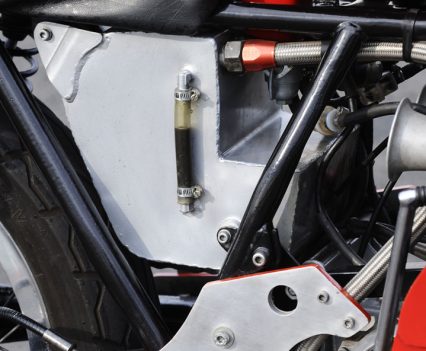

You have to stand on tiptoe to throw a leg over the Japauto, on account of the very tall seat back containing the battery, that’s accessible via a trap door on the right, secured by rubber bands. But once aboard you realise that at 805mm the seat itself isn’t too high, and that thanks to the indented rear squab you park your butt in, once aboard you’re wedged in place until your next pitstop – moving around in the seat is pretty difficult, and hanging off in turns strictly interdit.

When you’re spending hours at a time on an endurance racer. You need the riding position to be comfortable and natural, Alan reported that the 950SS is just that.

But the result is a relaxed, rational riding position that you get the impression would surely be good for the long haul, an untiring semi-upright stance that doesn’t place too much body weight on your arms and wrists as you reach forward over the capacious but not excessively bulky fuel tank to the pulled-back Bottelin-Dumoulin clipons, which are also quite steeply dropped.

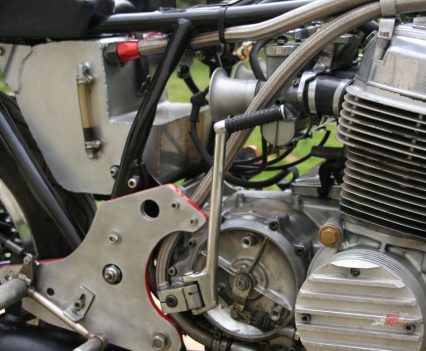

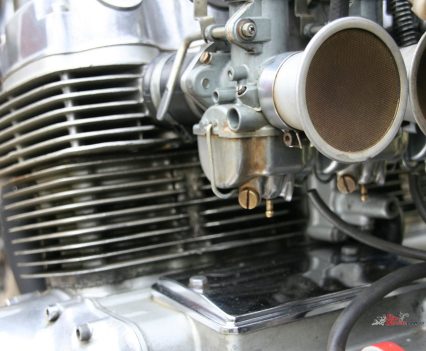

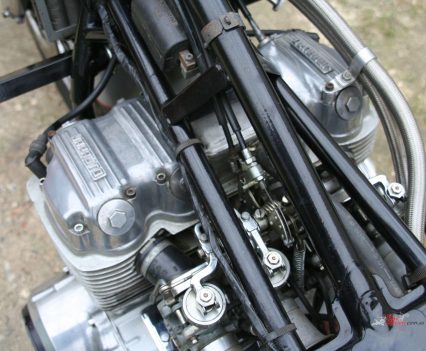

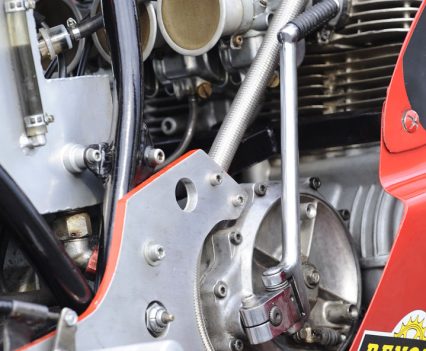

In spite of having an oil radiator to keep the six litres of lubricant cool, with a clear external tube on the right of the dry sump engine’s separate oil tank installed beneath the seat to monitor the level at pitstops, the only instrument you have to look at on this air-cooled in-line four is the tacho. This is redlined at 10,500rpm, which is a little too high for this big-bore 970cc engine fitted with the full Japauto customer engine kit to rev to safely – 1,000 revs less is better, says Patrick, with peak power of 85bhp delivered by this lightly tuned motor at 8,500rpm, with torque peaking at 7,200rpm.

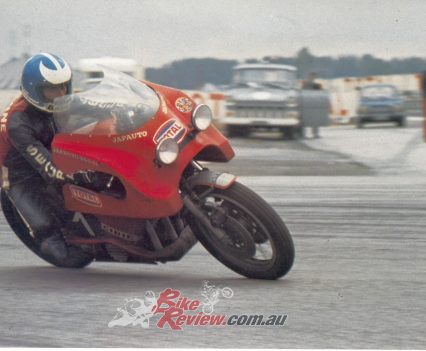

But thanks to the acres of grunt from this meaty motor, surfing the torque curve from 3,000rpm upwards and changing gear at 8,000rpm is the way to go, giving quite good acceleration by the standards of the era, if not quite as sharp as the Godier/Genoud Kawasaki 1975 Bol d’Or winner I’d ridden a couple of years earlier. But that had an extra two years of development on this Japauto, although as against that its twincam engine wasn’t so super-flexible and forgiving as the big single-cam Honda motor. I can see how this would have been a better ride in those awful conditions delivered by the torrential 15 hours of rain that Debrock/Tchernine had to endure in riding the original of this bike to victory in 1973 – it’s not exactly a pipe-and-slippers racer, but it’s the next best thing….

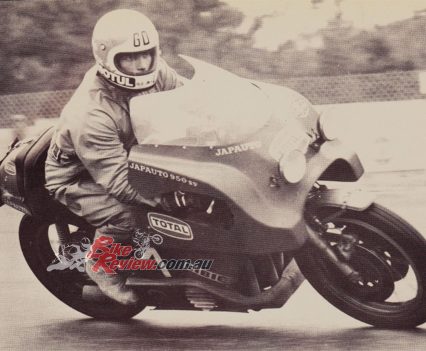

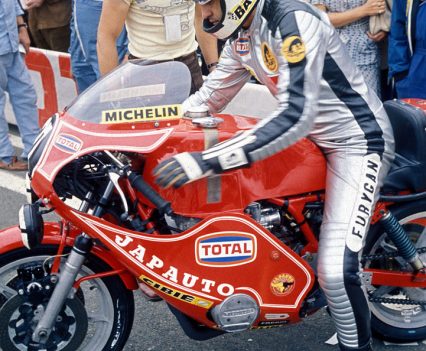

Funnily enough, the bike actually went faster without the fairing on. But the added protection aided riders in the rain.

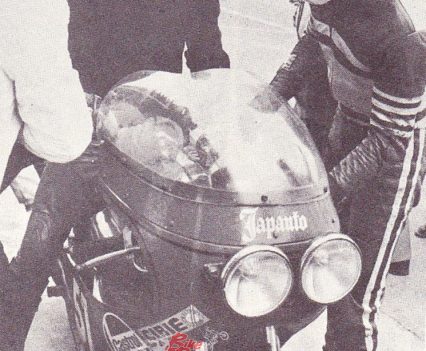

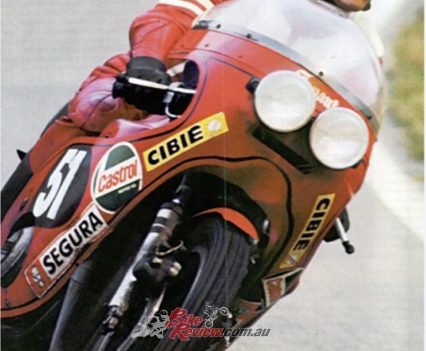

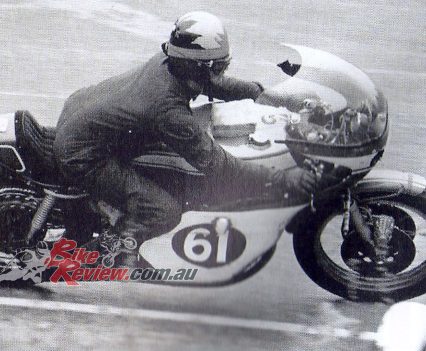

That strange-looking but effective Japauto bodywork would definitely have been an added bonus in the rain, as Debrock confirmed after the ‘73 race. It’s as avantgarde in effectiveness as it is in design, because at a time when its Endurance rivals either had a slim, wind-cheating, GP-style fairing or else none at all, the Japauto stood out by the protection it delivered to the rider. However, the penalty for this is often a sense of other-worldliness in riding the bike, a feeling of detachment thanks to the all-encompassing bodywork, which makes it hard to place the bike accurately in turns.

I suffered from this problem for many years when racing my XR750 Harley-Davidson, fitted with the voluminous Wixom fairing designed for the Daytona bankings, until I managed to source a set of the skinnier short circuit bodywork, and found the bike much easier to ride with that fitted. I’d expected the Japauto to deliver the same set of problems – but it doesn’t. I think perhaps the reason for this is the relatively low straight-cut screen, which acts as a wind deflector rather than a shield, so you end up looking over it rather than through it, as on the Harley.

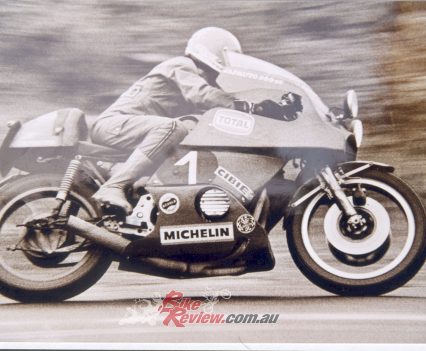

Another surprise was that the rangy 1500mm wheelbase of the 950SS, and its kicked-out 28º head angle for the stock 35mm Showa forks, didn’t make it unduly slow-steering. OK, it’s not exactly a 250GP racer, and with the 19-inch front wheel the steering is a bit heavy even by the standards of 40 years ago – a Norton or Triumph twin is definitely quite a lot more agile, but I didn’t expect the Honda chassis to be so relatively easy to change direction with in the trio of Magny-Cours chicanes.

I didn’t expect the Honda chassis to be so relatively easy to change direction with in the trio of Magny-Cours chicanes.

It was super stable round the French track’s long fast sweepers, where it felt solid and dependable as well as reassuring, and you could almost flick it from side to side in a chicane – it’s not too physical a bike to ride, which was a surprise, with that geometry. However, the suspension was a long way from being confidence-inspiring, chattering both wheels quite badly over the car-induced ripples in the Turn 2 right-hander leading on to the main straight, and although I never let it get out of hand, it certainly affected the drive onto the fastest part of the circuit.

“The suspension was a long way from being confidence-inspiring, chattering both wheels quite badly over the car-induced ripple.”

Equally disappointing, even by the standards of the era, were the brakes, twin 296mm stainless steel Honda discs here gripped by single-piston Tokico calipers off the CB500. Their design apparently made it easier to change brake pads more quickly during a pit-stop than CB750 ones, though Debrock/Tchernine didn’t need to do so during their ride to victory in 1973, probably on account of the wet conditions not posing too great an issue in stopping the bike.

But compared to the AP-Lockheed cast iron discs on the Ducati 750SS I took delivery of the following year after their victory, which had great initial bite and didn’t ever fade, the Japauto’s brakes were pretty ineffective. You must squeeze the lever very hard indeed while also standing on the pedal operating the rear drum brake, to get any sort of stopping power. “I don’t remember the brakes being so bad, and I certainly didn’t use the back brake very hard,” recalled Thierry Tchernine when I mentioned it to him. “But then I rode most of the race with a wet track, so you didn’t exaggerate the braking in those conditions.” Just as well, mon ami….

You must also be very emphatic in changing gear on the left-foot one-down shift lever, which dictates being very positive, especially changing up – the Japauto twice jumped out of gear some seconds after I’d hit a higher gear, presumably because I’d been too quick to assume it had actually gone in, when it hadn’t. The change is pretty slow at the best of times, although with that torquey motor and wide spread of power, that’s not such an issue. But the engine has a lovely linear build of power that’s also strong and determined – just that it’s measured rather than sprightly, and it won’t pick up revs very fast.

However, when you have a 970cc four-cylinder motor in the pre-Z1 Kawasaki days, and everyone else is on an 850 twin at best, that’s not so much of an issue. Clutchless upshifts worked just fine – although Thierry Tchernine admitted to me he never used the clutch at all when changing gear in either direction! Troy Bayliss never did either – but he had a slipper clutch and electronics to smooth out the gearshock on his Ducatis – is that why so many Japauto riders suffered from gearbox troubles??

The throttle action was also surprisingly slow, given that Japauto sold a quarter-turn throttle as part of their big bore kit, and I could see the magic name stamped on the test bike’s twistgrip. But it turns out that Patrick Massé had fitted a Japauto street-action throttle to the bike, with a much slower half-turn response which he thought would make riding it easier. Well, it might have done – except I had to pit three times in my 18-lap stint to get him to tighten the twistgrip rubber, which kept sliding off! Finally wired up right, I found the throttle action was way too slow, as well as heavy, making it hard to blip the throttle even on downshifts.

“Where the Japauto replica really scored was in the overall feeling of confidence it delivers – it feels very tight, well-built and together, and due credit goes to Patrick Massé for making it that way.”

But where the Japauto replica really scored was in the overall feeling of confidence it delivers – it feels very tight, well-built and together, and due credit goes to Patrick Massé for making it that way. Very much a child of the 1970s, the Japauto is nevertheless a forward-looking motorcycle that was as effective in its design as it was individual in its looks. They don’t make ‘em like that any more!

1999 Replica Of 1973 Japauto Honda 950SS Specifications

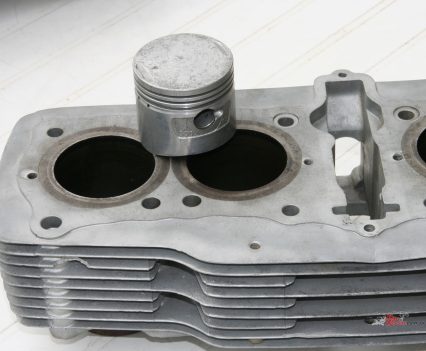

ENGINE: Air-cooled sohc transverse in-line dry sump four-cylinder four-stroke, with two valves per cylinder, and central chain camshaft drive, 969.80cc, 70mm x 63mm bore & stroke, 9:1 compression ratio, Nippondenso coil ignition + 12v battery, 4 x 28mm Keihin PW, 5-speed close ratio gearbox with duplex chain primary drive and electric start, multiplate oil-bath clutch with heavy-duty springs.

CHASSIS: Tubular steel double cradle frame, 35mm Showa telescopic forks (f) Two-piece welded stamped steel swingarm with 2 x Koni Shocks (r) 2 x 296mm Stainless steel discs with single-piston Tokico CB500 calipers (f) Single leading-shoe 180mm Honda drum brake. (R) 100/90-19 Bridgestone BT17 Battlax (F) 120/90-18 Bridgestone BT17 Battlax (R) Akront wire-wheels. 28 degree head angle. 1500mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 85hp@8,500rpm (at rear wheel), top speed 235km/h, 49/51 weight distribution, 208kg with oil/no fuel, including electric starter, twin headlamps, rear light and alternator

Owner: Patrick and Véronique Massé, Wy-dit-Joli-Village, France

Japauto Honda 950SS Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.

January 10, 2024

I liked the look of the side-headlamp version better – wonder which worked better on track?