Exactly 40-years after it was unveiled to the world, the GSX-R750F remains a hero. Sir Al tests the first ever Superstock Championship winning machine, twice! Photos: Jay Groat

It’s hard to think of any new model as immediately dominant straight out of the box as the Suzuki GSX-R750F was in its debut 1985 racing season. Nothing demonstrated this better than its supremacy in that year’s inaugural MCN Superstock British Championship…

The new GSX-R750F dominated the first ever series run anywhere in the world to carry the Superstock name, winning nine of the eleven races. Veteran star Mick Grant, then 41, won the first four rounds in succession, proving he didn’t need to apply for the pension book just yet by convincingly wrapping up the title with five victories in the end on the bike entered by UK importers Heron Suzuki, and sponsored by adult magazine Men Only.

Read Alan’s story about the history and development of the GSX-R750F here…

Every race in the series offered nail-bitingly close racing between topline riders on evenly-matched machinery which the average spectator could readily identify with – the whole rationale of the Superstock category, and today’s Superbikes. Dipping in and out of each other’s slipstreams, sitting it out three abreast under braking for chicanes or hairpins, swapping the lead half a dozen times a lap, these Super-headbangers on their Superstockers revitalised a UK racing scene that was then flagging because of the economic downturn.

“Veteran star Mick Grant, then 41, won the first four rounds in succession”… He also won the Isle of Man Production TT on a box-stock version ahead of three other Suzukis. Mick Grant is pictured here on the aluminium-framed XR69 at the IoM TT in 1983.

The key ingredient of a series enthusiastically supported by three out of the four Japanese manufacturers, was that it pitched sporting streetbikes like those lined up in the spectator bike parks against each other with a minimum of tuning. As such, it represented the British counterpart of the AMA Superbike category, which was christened as such by the man who invented that streetbike-derived category in the USA in 1973, British expat Bruce Cox.

Check out our Old V New GSX-R750 test here…

He’d returned home to the UK in 1982 to run the no-holds Yamaha RD350LC ProAm series, then dreamt up and promoted the Superstock category. “I wanted to bring our Superbike concept to Britain, but without the expense of tuning the engine, which by then had started to fragment the AMA field between the importer-backed teams and the true privateers,” says Cox. “The bikes needed to be proper racers, which is why we let them run slick tyres and gave them complete freedom for brakes and suspension, including the swingarm.

Standard carburettors were part of the Superstock rules. Fortunately the GSX-R750F already had race carb’s…

“But it was important we retained the silhouette of the stock model, so they had to run standard bodywork, and you weren’t allowed to alter the main frame loop – no cut ‘n’ shut on the steering head, for example. But the most important thing was the engine had to be 100% stock, and that included the carbs – we caught Yamaha machining theirs and turning them into smoothbores, for example, which meant Steve Parrish got kicked out of the results at Snetterton!

“The result was that impecunious privateers like Terry Rymer, whose dad prepared their bike in the garage behind their home, could compete with the better funded importer entries, and win races. That’s why I called it Superstock – Superbike chassis mods, but stock engines. Seems like the name caught on, as well as the concept. I should have registered it!” Indeed so….

“It was important we retained the silhouette of the stock model, so they had to run standard bodywork, and you weren’t allowed to alter the main frame loop – no cut ‘n’ shut on the steering head”…

However, there was still one way that an importer team had an edge over its customer rivals, and that was when it came to getting hold of any new model in time to do meaningful development on it before the start of the season. Easter came early in 1985, with the MCN Superstock series kicking off on April 5 at the Brands Hatch Good Friday meeting as a support class to the Transatlantic Trophy USA/UK series, which Cox also promoted.

But the first GSX-R750F shipment from Japan had barely docked, meaning that even if they were lucky enough to get hold of a bike, customer teams had no time to do much more than stick race numbers on a stocker and tape up the headlamp – whereas the Heron Suzuki team had taken the precaution of flying the first of the new bikes straight from Japan to the UK early in the New Year, giving plenty of time for their mechanics Paul Boulton and Nigel Everett to prep it up, and Mick Grant to go testing on the first production GSX-R750F in Europe at Donington Park, before the start of the season.

The GSX-R750F did not arrive in the UK until just before the first round… This is our Editor Jeff’s bike that he restored.

Time was vital in making the new Suzuki Superstocker at all competitive, let alone a winner, recalls Paul Boulton. “We’d read all the factory literature quoting 100bhp, so when we got just 73bhp at the gearbox after running it in, you can imagine the reaction!” he says. “So we double-checked it on another dyno – same reading.

“We’d read all the factory literature quoting 100bhp, so when we got just 73bhp at the gearbox after running it in, you can imagine the reaction!”

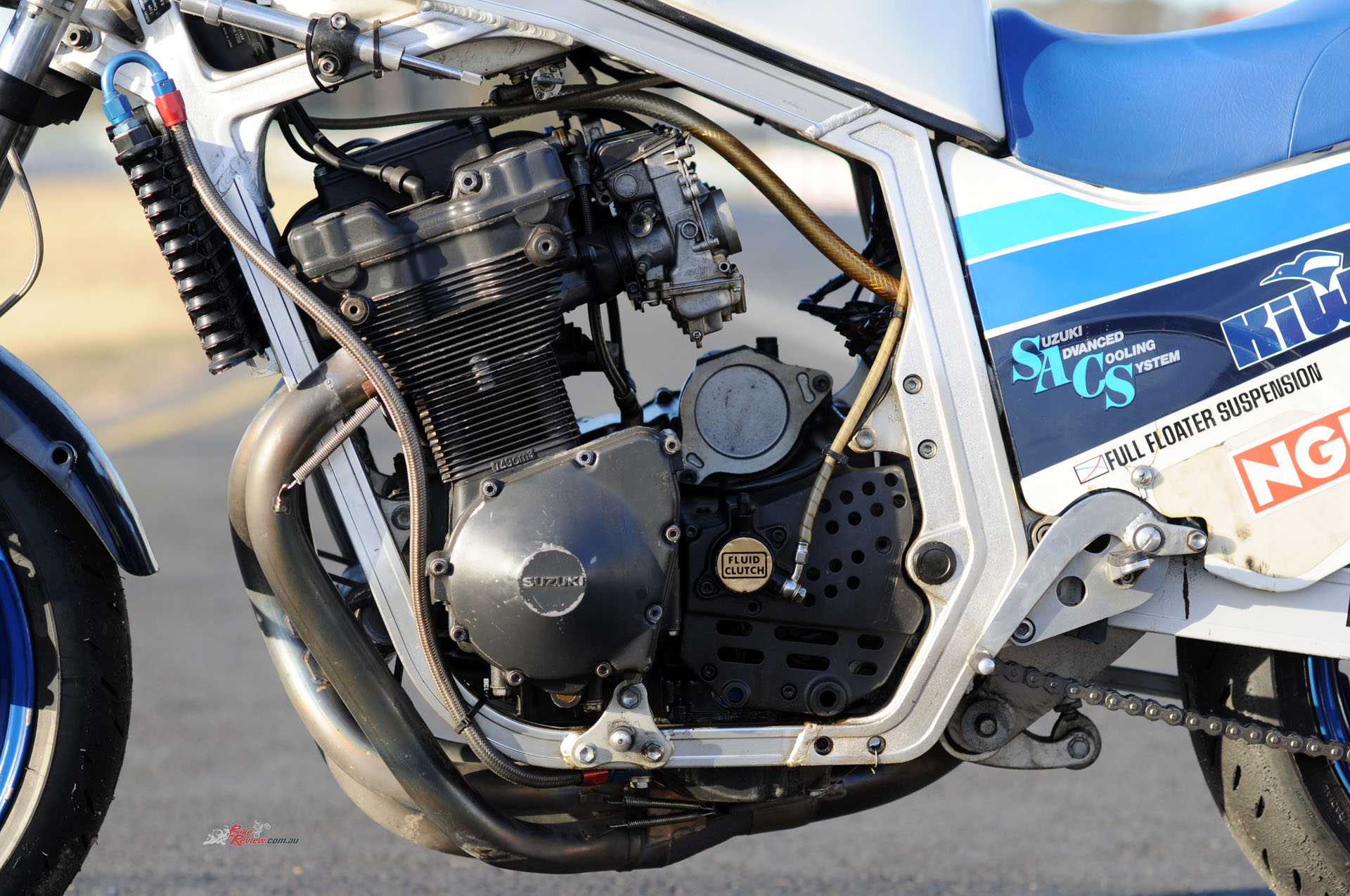

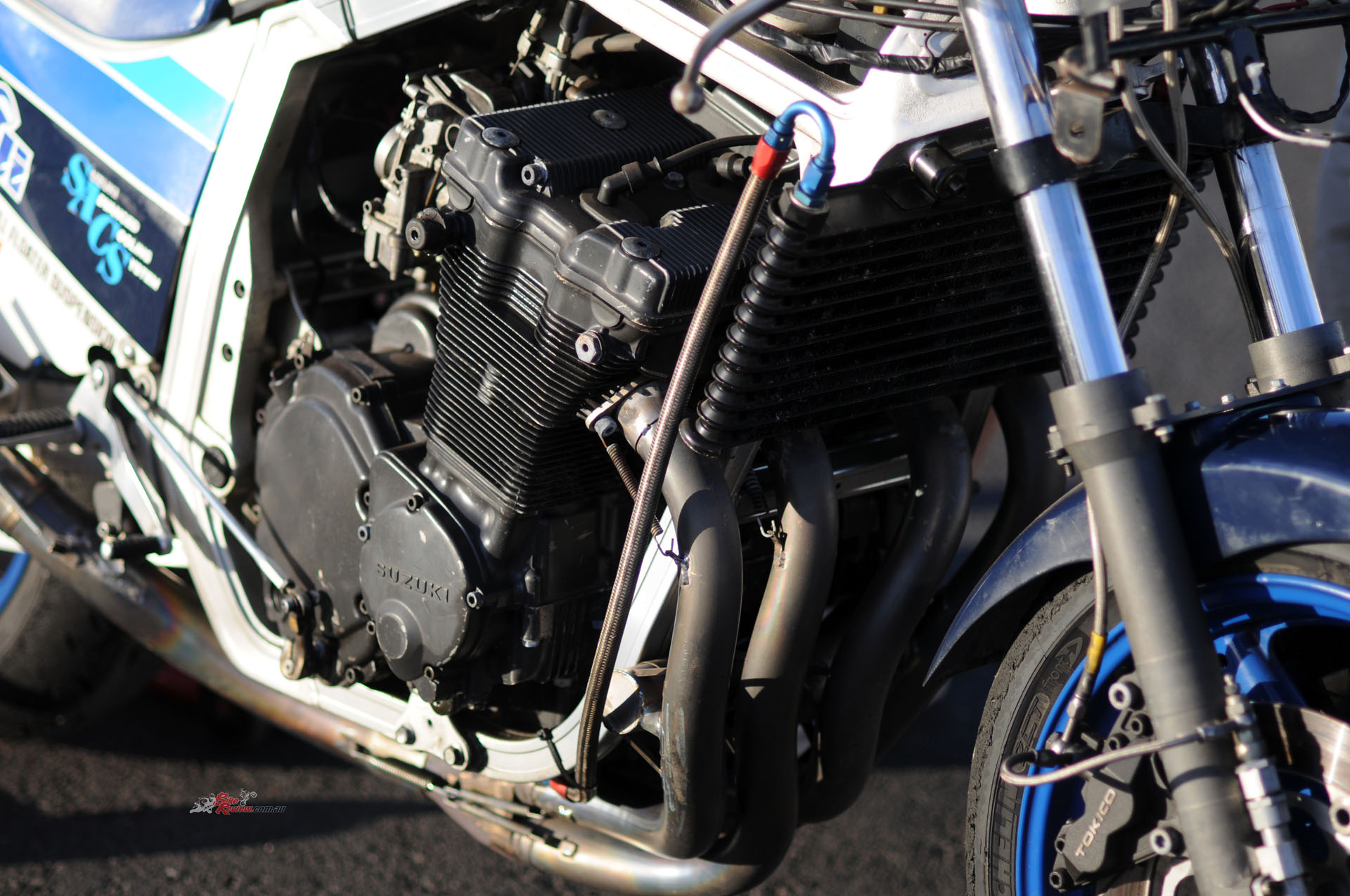

“However, blueprinting the engine and progressively modifying it within the rules brought it up to scratch – we fitted a factory titanium race exhaust off the TT1 bikes, removed the airbox, increased main jet sizes from 97.5 to 130 on the stock carbs, cleaned up the cylinder head, raised compression from the stock 9.8:1 to 10.7:1, removed the generator and ran a total loss battery – and got a genuine 96 bhp at 10,500 rpm, which was a bit better!”

“We’d read all the factory literature quoting 100bhp, so when we got just 73bhp at the gearbox after running it in, you can imagine the reaction!”

Mick Grant takes up the story. “I’d been riding full time for Suzuki since 1982, and I really enjoyed racing the RG500 two-stroke GP bike, with the TT Formula 1 as my only four-stroke ride. But for 1985 Denys Rohan [then the boss of Heron Suzuki – AC] wanted to promote the new GSX-R750F by getting me to ride it in this new Superstock class, which I absolutely did not want to do – I could see that with stock motors there’d be lots of young nutters out there trying to make a name for themselves by beating Mick Grant with a bike they could put on the grid for 5,000 quid.

“Well, in the end we did a deal, and I agreed to do the series against my better judgement – but then we got the bike early, set it up, and I won the first four races on the trot with it, after which it all seemed a bloody good idea! It was a lovely thing to ride, and extremely reliable, built like a Swiss watch. I also won the Isle of Man Production TT on a box-stock version ahead of three other Suzukis, and it was rock solid everywhere and rode bumps well – but only after I’d changed the tyres.

“I was contracted to Michelin, but all through practice the Suzuki was very unstable on them, so I tried to buy some Pirellis to see how they’d go. I wanted to pay for them myself, so they couldn’t use my results in adverts, but Pirelli gave me the tyres for free, and promised there’d be no advertising. They worked beautifully, so I won the race – but the following week Pirelli were using my picture in their adverts proclaiming that fact, which as you can imagine went down like a lead balloon with Michelin!”

“The only time I fell off the Superstocker was after just four laps in the very first pre-season Donington practice, and I remember thinking as it flicked me in the air – what am I doing riding this piece of c**p?! It turned out Suzuki had used too coarse a thread on the oil filter, which had come unscrewed – we had to wrap a jubilee clip around it to stop that happening, and the first batch of customer streetbikes all over the world had to be rectified like that, until they produced new cases with a finer thread to stop that happening.”

“By the time I’d won my fourth race, rumours were flying about that the engine wasn’t standard,” continues Mick.

“By the time I’d won my fourth race, rumours were flying about that the engine wasn’t standard,” continues Mick. “But it truthfully was, except for the ignition box we fitted which allowed another 500 revs before the limiter kicked in, just to hold a gear between turns and save a pair of gearchanges, like at Snetterton between the Esses and Bomb Hole. So at Donington I asked Rod Scyvyer, the chief ACU scrutineer, to let us strip the engine down in front of everyone after the race, and get him to check it – which he did, and of course it was OK. That stopped the muttering, and after that it was just fine – a very faithful friend of a bike that’s still fun to ride today.”

Indeed so, because after retiring from racing at the end of 1985 – his October ride to a title-clinching 7th place on the Gixxer in the final Superstock round at Brands Hatch was Mick’s final UK race, followed by his victorious last-ever outing in the Macau GP a month later on the RG500 – Grant obtained his title-winning GSX-R750F from Heron at the end of the following season, in which Kiwi Glenn Williams raced it for the UK importers, without notable success.

GSX-R750F frame no. GR71-00719 carrying engine no. R705.104962 still has the scrape on the fuel tank and the dented frame…

But mechanic Nigel Everett had taken the precaution of removing and storing all the Grant hardware in order to put it back to exactly how it was when Mick crossed the line in that final Brands round – which explains why, 40 years on, GSX-R750F frame no. GR71-00719 carrying engine no. R705.104962 still has the scrape on the fuel tank and the dented frame sustained in that pre-season Donington crash, as well as the trademark Grant No.10 plates (a number chosen because simply he was born on the 10th of July, insists Mick!). It’s history on wheels – and one I was twice able to sample from the hotseat…..

Alan’s 1985 Test

For the Thursday after Mick’s title-clinching Brands Hatch outing in 1985, Heron Suzuki team manager Rex White arranged for me to ride the championship-winning Superstocker at Snetterton, as well as to sample the team’s factory GSX-R750TT1 bike with a more highly tuned Yoshimura engine in a full-race chassis, on which Grant had finished second to the V4 Hondas in both the World and British TT F1 Championships. The Suzuki had proved no match at World level for the ’85 RVF750 V4 of Joey Dunlop nor, indeed, in the British title race for the ’84 RS750R V4 of Roger Marshall. Paul Boulton was there with Nigel Everett to look after the bikes, and the first question he had to answer for me was – how come the Superstocker had the same suspension as the TT1 racer?

“First question he had to answer for me was – how come the Superstocker had the same suspension as the TT1 racer?”

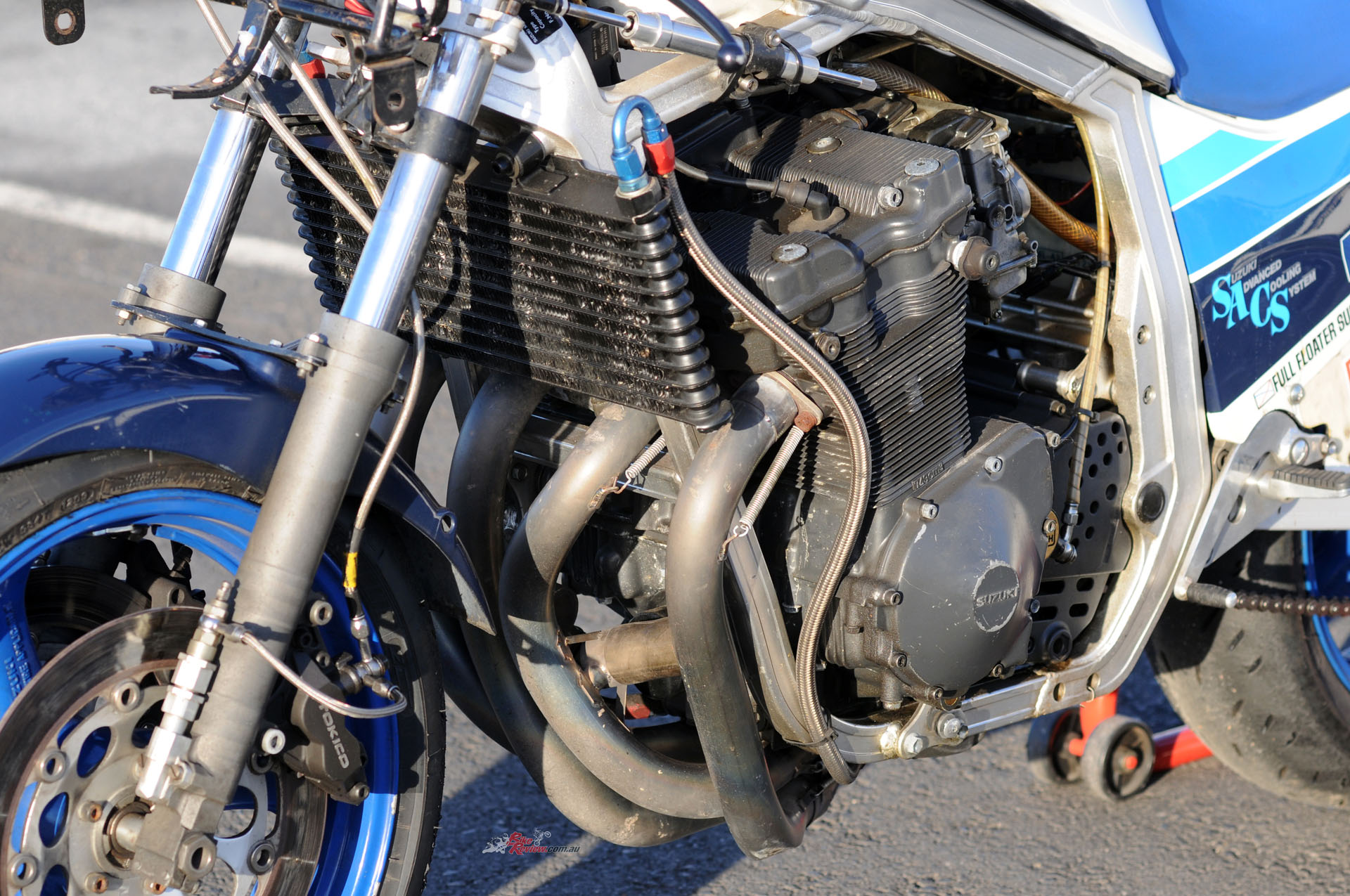

“Mick reckoned the offset on the standard yokes was too flat, combined with a pretty steep 23° head angle for a road bike and the 18in front wheel,” explained Paul. “Anyway, we wanted to fit 16in wheels so as to use the same Michelin tyres as the other bikes we’ve been running, and because he knows the range of compounds better. So after checking we had complete freedom under the Superstock rules with suspension, wheels and brakes, we took the whole front end off one of the air-cooled XR69 TT F1 bikes, which is basically the same as Randy Mamola’s XR45 GP bike, with 40mm Kayaba forks and hydraulic anti-dive, and 310mm Brembo brakes with four-piston Tokico calipers, and bolted it right on. The 16in rear wheel went straight in, we fitted a White Power rear unit with standard linkage giving four inches [101mm] of travel, and won the first four races in a row.

“People thought we’d done something to the engine, but it wasn’t that – Mick just rode bloody well, and after his early season dominance he could afford just to pick up places from then on, and still win the title.” So he did, with 128 points to 98 for closest rival Roger Marshall’s Honda VF750F – matching the achievements that year of other GSX-R750F riders like Juan Garriga in Spain, who dominated both TT F1 Silhouette and Prototype racing there on his Suzuki, or Rob Phillis in Australia, beating GPz900s and VF1000s with his ‘little’ 750 in the Production class. The Suzuki GSX-R750 delivered on its promises – it was a grid gracer as well as a street racer.

Jumping Back On in 2015

One that I made my re-acquaintance with three decades later at the South African TT Revival series run by Mick Grant each year as a series of three race meetings essentially run as glorified track days. You guessed it – Ol’ No.10 was one of the two dozen ‘interesting’ bikes shipped out to EssAy for the series from the UK, by then owned by tyre specialist and former road racer Tony Salt, who’d pestered Mick long enough to sell it to him that he finally did so eight years earlier. “I still get to ride it whenever I like, so I suppose it’s the best of all worlds!”, says Grant with a smile – and thanks to Salt’s generosity I got to cover 20 laps of Cape Town’s Killarney GP circuit on the Gixxer, while he relaxed on pit wall with a tall glass of fruit punch brimming with ice cubes, which he thoughtfully displayed to me each lap instead of a pit board, as I screamed the Suzuki past him in the sweltering South African heat. So thoughtful….

“Clambering aboard the GSX-R delivered a real surprise – I’d forgotten how low the seat was, especially compared to later 750 Superbikes”.

This trip down memory lane was made complete by having ex-Heron Suzuki 500GP mechanic, now leading historic race engine restorer, Paul Boulton on hand three decades on to look after the bike once more, and to remind me of some reference points from both our yesterdays as he warmed it up for my first outing at Cape Town. With more than five litres of oil in the wet-sump engine, this was doubly important on the oil-cooled Gixxer, making it curious that its minimalist dash consisting of an ignition key which must also unlock the seat (an arcane requirement of the Superstock class, presumably as lip service to the fact this was once a streetbike) and a stock white-faced tacho, no longer featured the oil temperature gauge that was on the bike when I first rode it back then. (Strangely, there never was one monitoring the oil pressure as well, which you’d think was rather important on this bike). With the aid of the large oil cooler mounted in front of the cylinder head, normal running temperature was actually 100-110°C, and Heron Suzuki dyno tests showed the hotter the engine ran the more power it produced – presumably as tolerances were taken up.

“Tony Salt had installed 17-inch wheels off a current GSX-R750F to be able to fit modern Michelin Pilot One rubber”…

Clambering aboard the GSX-R delivered a real surprise – I’d forgotten how low the seat was, especially compared to later 750 Superbikes, though even the contemporary FZ750/VF750 had you sitting higher up, and also how cramped the riding position was once you’d inserted yourself into the thickly padded seat which seemed improbably plush for a racer, practically like an armchair. You were effectively wedged in place, and it took some manoeuvring to hang off the side in turns, making Mick Grant’s trademark economical style of sitting in place while using the good grip of the modern Michelin Pilot One street tyres to crank it on its side, the hot tip for riding this first-series Gixxer.

“The right-foot one-up gearshift conversion was done back then by Heron themselves to accommodate Mick Grant’s tastes”…

No wonder it was such a fantastic bike for endurance racing. Tony Salt had installed 17-inch wheels off a current GSX-R750 to be able to fit modern Michelin Pilot One rubber, rather than the 18-inchers it came with as stock, or the 16-inchers Grant raced with, for which tyres were by then unobtainium. He’d also mounted a plate above the exhaust on which to position your right heel instead of barbecuing it on the pipe, but the right-foot one-up gearshift conversion was done back then by Heron themselves to accommodate Mick Grant’s tastes – well, if you learn to go racing on a Velocette, old habits die hard.

“A genuine 159kg with oil but no fuel, a significant saving on what was already a light bike for the class.”

Lowering the ride height by fitting 16in. wheels didn’t cause any ground clearance problems when I rode the bike on grippy Michelin slicks 40 years ago, but it did accentuate the feeling of sitting low down within rather than on top of the Suzuki that was already noticeable with the standard road bike. Yet stripping the GSX-R out for racing as you did for Superstock racing removed most of the sensation of riding a streetbike. Gone were the twin headlights, speedo, rear light and indicators, which together with removing the starter motor and generator brought the weight down from that perhaps optimistic claimed 176kg dry in street trim to a genuine 159kg with oil but no fuel, a significant saving on what was already a light bike for the class.

Leaving the Killarney pits brought another surprise – the stock flatslide Mikuni carbs had a very stiff throttle action, brought about because of the heavier return springs fitted to counter the suction effect which apparently led to them occasionally sticking open in Grant’s hands, until these were installed. Coupled with the sudden pickup of the flatslides compared to a conventional CV carb, this made it easy to spin the back wheel until the triple-compound Michelin had warmed up, and I had to learn how to preload the throttle slightly exiting a turn, before cracking it wide open for maximum drive. The stiff action also made it hard to blip the throttle for downshifts under heavy braking.

“I had to learn how to preload the throttle slightly exiting a turn, before cracking it wide open for maximum drive.”

Accelerating down to the first left-hander brought the next surprise – the brakes didn’t work! To be fair, Tony Salt had warned me about that, so I was ready for having to squeeze very hard to make them work not very well when cold. Taking a leaf from the carbon brake operation manual, I held the lever on lightly as I completed the first lap, after which they worked well enough to stop the Suzuki at the end of the 800 metre-long back straight doubling as a drag strip, but even after they’d warmed up they seemed rather wooden – something I also complained of back in my 1985 test of the bike, so this wasn’t a case of modern expectations of 40 year-old hardware. The Suzuki just didn’t stop as well as I’d expected with those 10mm bigger Brembo discs than standard, and it also required a pretty high lever effort. Thinking back I remember this was an issue when Brembo swapped not long before the Suzuki raced from cast iron to stainless steel material for their discs, so maybe that was the reason. At least the Superstock GSX-R stayed on line and didn’t sit up under braking when cranked over, as I remember from my Snetterton test its unruly-handling race-framed TT1 counterpart had done.

The GSX-R Superstock motor had a high idle speed of 2,500rpm, a favourite trick of Suzuki in particular back then in those pre-slipper clutch days aimed at preventing engine braking upsetting the handling – that’s why Frankie Chili’s Alstare Corona GSX-R750F Superbike had the same high idle speed 35 years later. This meant I didn’t have to worry about chattering the rear wheel anchoring up from high speed for Killarney’s second-gear hairpins – first gear on the Gixxer was just for getting off the line – and it also helped overcome that fierce pickup from a closed throttle via the flatslides and heavy springs. 40 years on, the great-sounding Superstock motor was still a lovely engine to ride, pulling smoothly from low down with no flat spot caused by the race pipe that was probably developed by Yoshimura, having been lifted off by the Heron Suzuki team off a factory-built TT1 racer.

The untuned engine had good midrange torque, although the effect of the open pipe and carburation changes had been to make the power delivery quite a bit peakier – there was usable poke only from 5,000 rpm onwards, but the real kick didn’t come until 7,000 revs, giving a relatively narrow usable powerband for a four-stroke 750cc roadster, before the 10,500 rpm revlimiter kicked in on the stock igniter box that Tony Salt had by now fitted, instead of the higher-revving ringer used by Grant. But the ratios on the standard six-speed gearbox were so well matched it was easy to keep the engine driving, though I found it difficult to change up smoothly every time without using the clutch. Although the race-pattern right-foot gearchange felt reasonably precise and clean, there was a fair bit of crankshaft inertia despite the much lighter crank than the old air-cooled GSX750, so fanning the clutch lever to get smoother upward changes didn’t result in any dramatic loss of revs.

“The ratios on the standard six-speed gearbox were so well matched it was easy to keep the engine driving”…

When it was first launched the GSX-R750F acquired a reputation as a rewarding if demanding streetbike, what the French call a ‘nervous’ motorcycle that would occasionally flap the front end unpredictably, or at worst if not set up right the possessor of twitchy, skittish handling and on some tyres as Mick Grant found at the TT, an insidious high-speed weave. We’ve since come to take some of this for granted as the entry ticket to race-quality handling, where if you get it wrong you must work at dialling out your setup mistakes, but back then when men were men and bikes were expected to be solid and planted in their steering, if you didn’t have to raise a sweat slinging it from side to side through a series of turns, then it was ‘nervous’.

The Suzuki was the gateway to the modern world, and the combination of its lightweight chassis and the racing suspension on the Superstocker, resulted in a surprisingly modern-seeming bike you could chuck around and enjoy, rather than have to tame. Though Mick Grant recalled it did occasionally set up a high-speed weave on him, I’m glad to say that never happened to me either at Snetterton 40 years ago or Cape Town today, and though I was rather cautious with it to begin with after the tales I’d heard of sudden misbehaviour, I soon realised this was a nearly vice-free bike.

The steering was neutral, there was no sign of tuck-in when leaned hard over, even on the brakes, and the suspension coped ideally with the many bumps on the Killarney circuit, where other more recent bikes got badly unsettled, especially with the power on. If ever the Suzuki was going to twitch, it’d be there – and it didn’t. The front end tended to wash out a bit round the fast left-hand sweeper on to the Killarney main straight, but that’s where a bit of muscle came in useful to pull it back on line, and I was impressed how well it rode the circuit’s many bumps, especially leaned over in a fast turn, where the low cee of gee with rider installed would have been a positive factor. It leapt around a little at speed down the long main straight, but the front wheel didn’t flap and it stayed going where it was pointed. Not bad for 40 year-old suspension at something approaching 240kph.

The Gen 1 893cc Honda Fireblade CBR900RR is always quoted as the first sportbike of the modern era – but eight years before it appeared, Suzuki got there first with the GSX-R750F, beating Honda to the punch by creating a 750 with the performance of a 1000, but the handling of a 600. In the context of the mid-1980s this was a truly revolutionary motorcycle, and the fact it’s worn so well that 40 years on down the line, Mick Grant’s title-winning Superstock version is still such a satisfying bike to ride, is a due mark of its significance.

1985 Suzuki GSX-R750F British Superstock Specifications

Engine: Oil-cooled DOHC 16-valve transverse in-line four-cylinder four-stroke, chain camshaft drive, 70 x 48.7mm bore x stroke, 749cc, 10.7:1 compression ratio, 29mm Mikuni VM29SS flatslides, Kokkusan-Denko CDI, wet multi-plate clutch, six-speed gearbox, four-into-one exhaust.

Chassis: Square-section tubular alloy double cradle frame, braced alloy swingarm, 40mm KAYABA forks with hydraulic anti-dive, White Power monoshock with Full Floater linkage, 1440mm wheelbase, dual 310mm Brembo floating steel discs, Tokico four-piston calipers, 220mm rear disc, twin piston Tokico caliper, 120/70 – 17in and 180/55 – 17in Michelin tyres, Suzuki cast alloy wheels, analogue tacho.

Performance: 159kg oil/no fuel, 240km/h top speed, 96hp@10,500rpm at gearbox. Owner: Tony Salt/TST Tyres, Warrington, Cheshire, Great Britain.