Sir Al farewells Canadian Michelle Duff, who transitioned from Mike in the '80s and recently passed away at her Nova Scotia home aged 85... Photos: Motorcycle Mojo and AC Archives

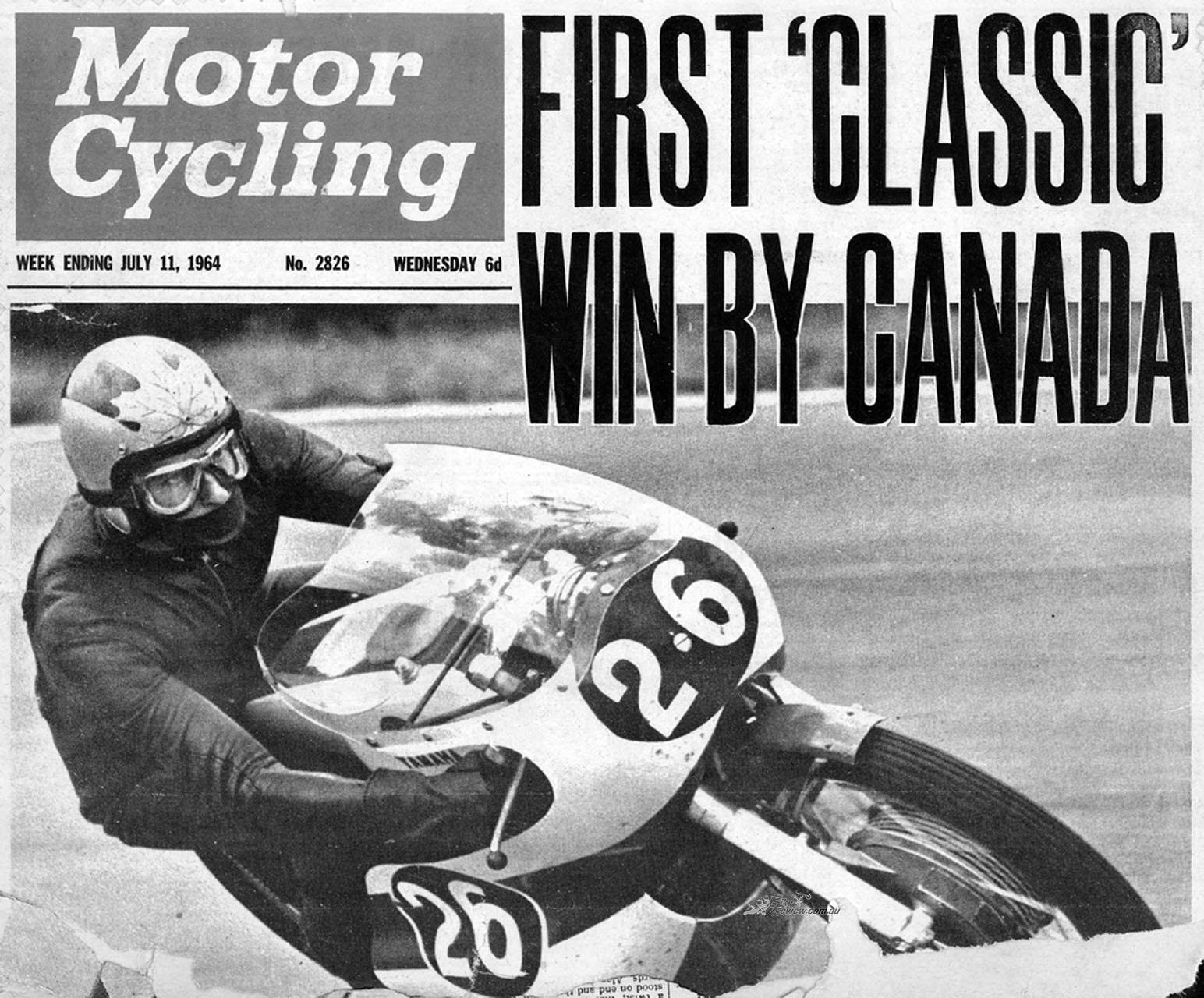

The first ever road racer from North America to win a World Championship GP race wasn’t Kenny Roberts, nor even Gary Nixon or Pat Hennen. It was the man perpetually typecast as ‘Canadian Mike Duff’, who scored the first of his three GP victories in the 1964 Belgian GP…

The win was at Spa on a Yamaha RD56, in just his second race aboard a factory entered motorcycle. Duff, who recently passed away on July 23, 2025, aged 85, after transitioning to Michelle in the mid-1980s, finished runner-up to teammate Phil Read in the 1965 250GP World Championship. Then, after bidding farewell to GP racing with a third place rostrum finish from the back of the grid in the one and only Canadian 500GP race held in 1967, Duff retired from racing in 1969 after finishing third in that year’s Daytona 200, and making a clean sweep of the 250cc, 500cc and 750cc Canadian Championships aboard self-tuned air-cooled production Yamaha TD2/TR2 twins supplied by his country’s Yamaha importer Fred Deeley. But his biggest challenge was yet to come.

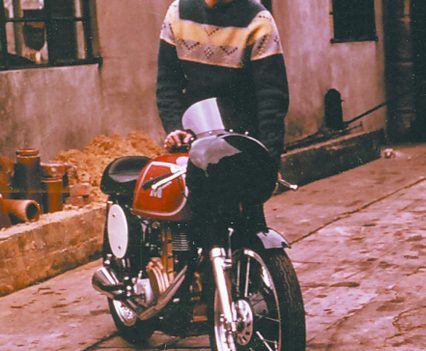

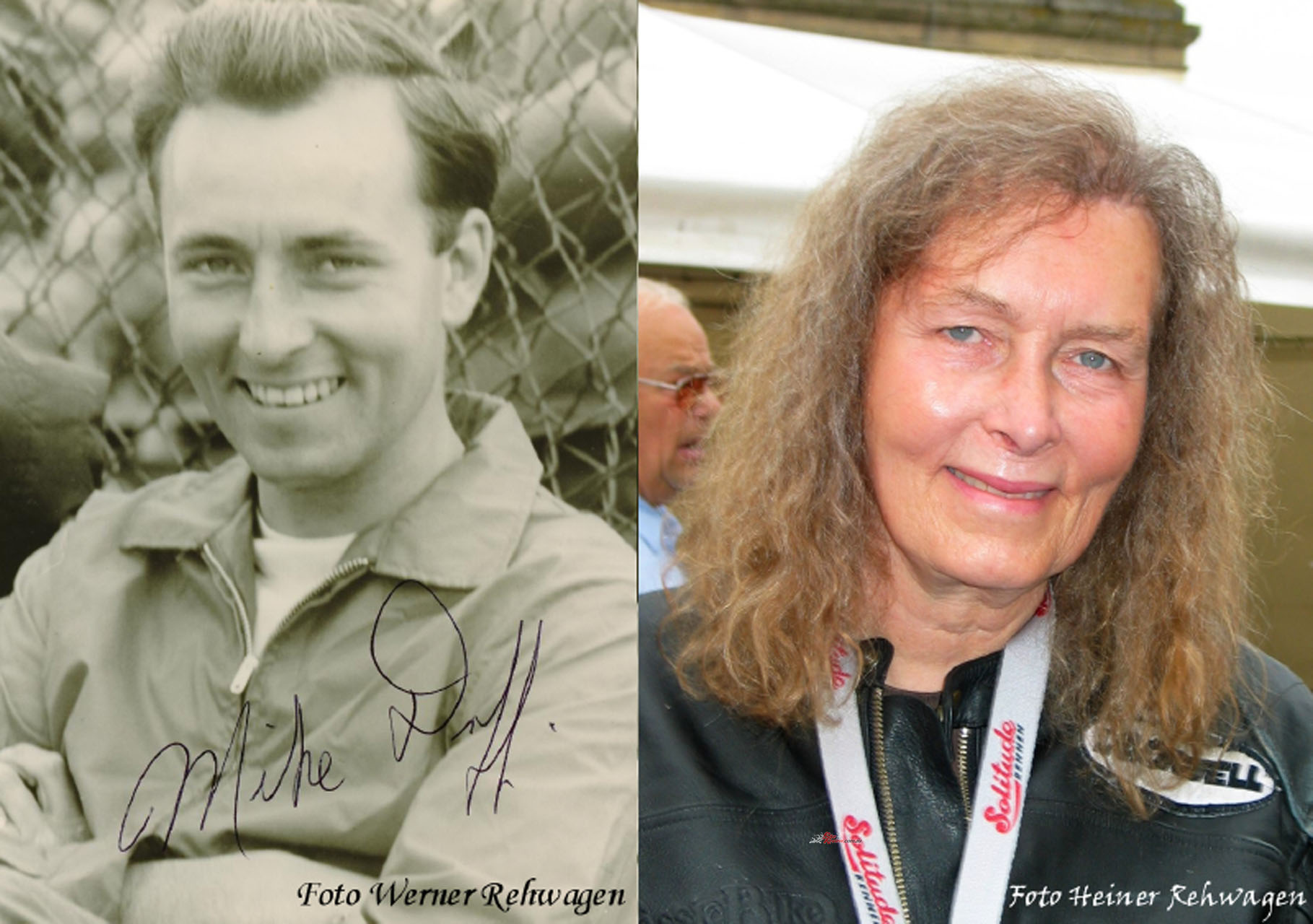

Canadian motorcycle legend Mike Duff and later in life, Michelle Duff. Michelle passed away earlier in the year…

Born Michael Alan Duff on December 13, 1939 in Toronto’s northern suburbs, Duff became fascinated by motorcycles and motorcycle racing at a very young age. “When my elder brother Stuart was in high school, one of his friends had an old Levis bike he often stopped by my parents’ house on, and it simply fascinated me,” she told me back in 2017 when I interviewed her about her life.

“When my elder brother Stuart was in high school, one of his friends had an old Levis bike he often stopped by my parents’ house on, and it simply fascinated me”…

“Then in 1952 when I was just 13, Stuart bought a 1949 250cc BSA, and we’d go for rides together, me sitting on the back mudguard. Watching him taught me how to start the bike, so after he moved on to a car and left the bike just sitting there, I began sneaking it out of the garage without permission, and taking it for rides. Handling the BSA came quite naturally to me, but when my parents caught me, they locked it away in the basement”…

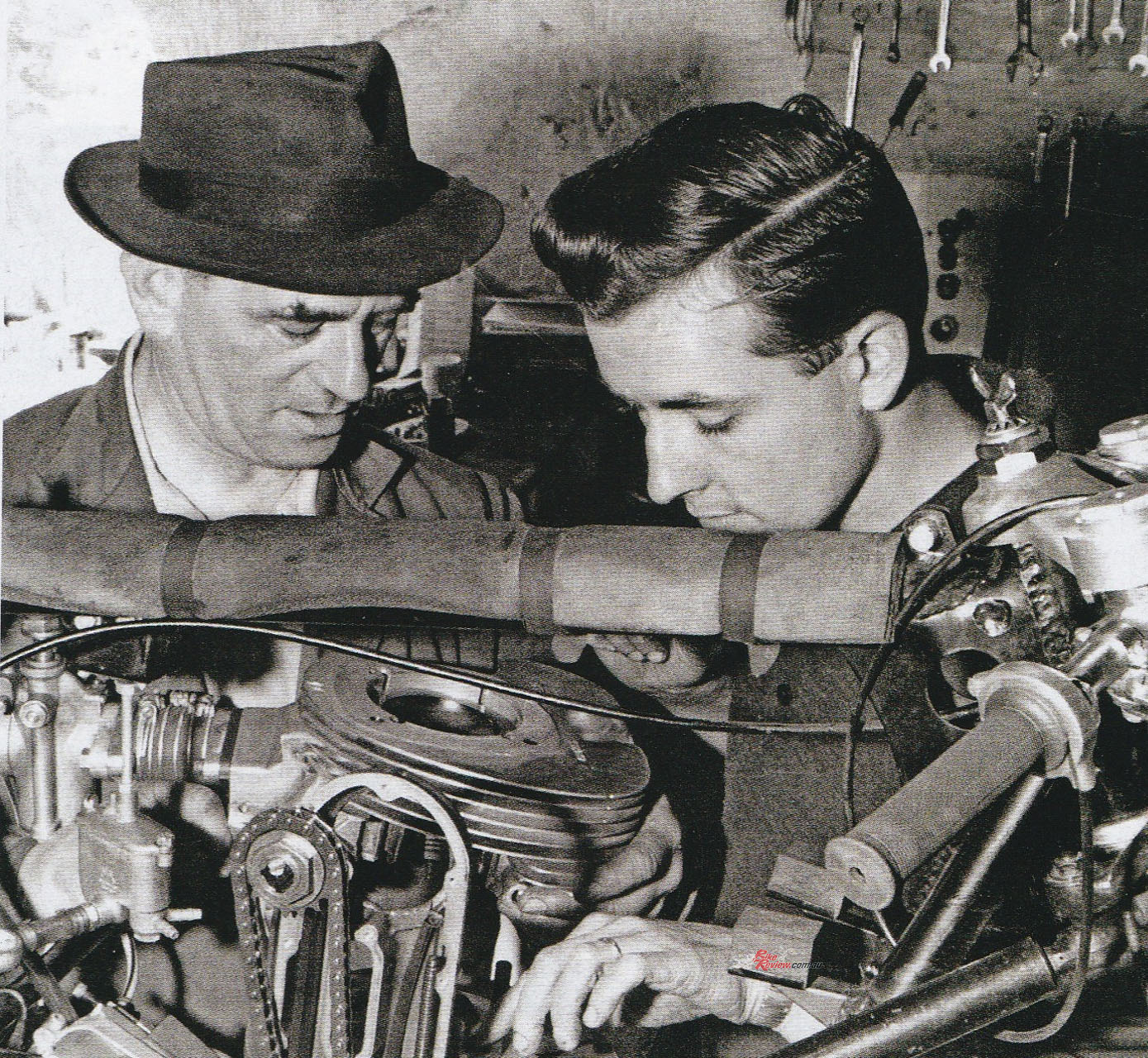

Mike Duff in 1954 on his brother’s 1949 BSA 250, he would sneak out for rides on it! Eventually he got caught out.

Duff was grounded for four weeks, and the BSA was to be sold in the spring. However, Mike talked his parents into letting him work on the bike over the winter – ostensibly to get it ready for sale. When spring arrived, they let him take short rides on the BSA – but he soon progressed to a faster, bigger model, purchasing a 1949 Triumph 500 Speed Twin with the proceeds of his Toronto Star newspaper round. The bike needed a complete overhaul, and his father Alex thought the rebuild would take at least six months. “My dad worked for Remington Rand, and he would design and invent things,” Duff said. “We had a decently-equipped workshop at home, and some of my mechanical dexterity was probably thanks to playing with Meccano when I was young.”

Instead of six months, the Triumph twin was on the road in four short weeks. On it, Mike began venturing further from home, and in 1954 rode 75mi/120km north to attend a road race near Barrie, Ont. The Duff-built Triumph ran flat out all the way there and back without missing a beat, and after watching the races Mike Duff had a new goal in mind. He wanted to go racing himself.

After watching the races Mike Duff had a new goal in mind. He wanted to go racing himself.

This led to the purchase the following winter of a 500cc Triumph Tiger racer which arrived in five separate boxes, complete with some go-faster goodies like higher-profile cams and a twin-carb conversion. Plus, while equipped with a rigid frame as standard, it had the optional Sprung Hub conversion which offered some measure of rear suspension. “My dad thought it would take me about a year to put it together, but I had it running in two months,” Duff said. “I was 15, and managed to convince my parents I should go racing with it, so they signed the release forms, and we went racing together.”

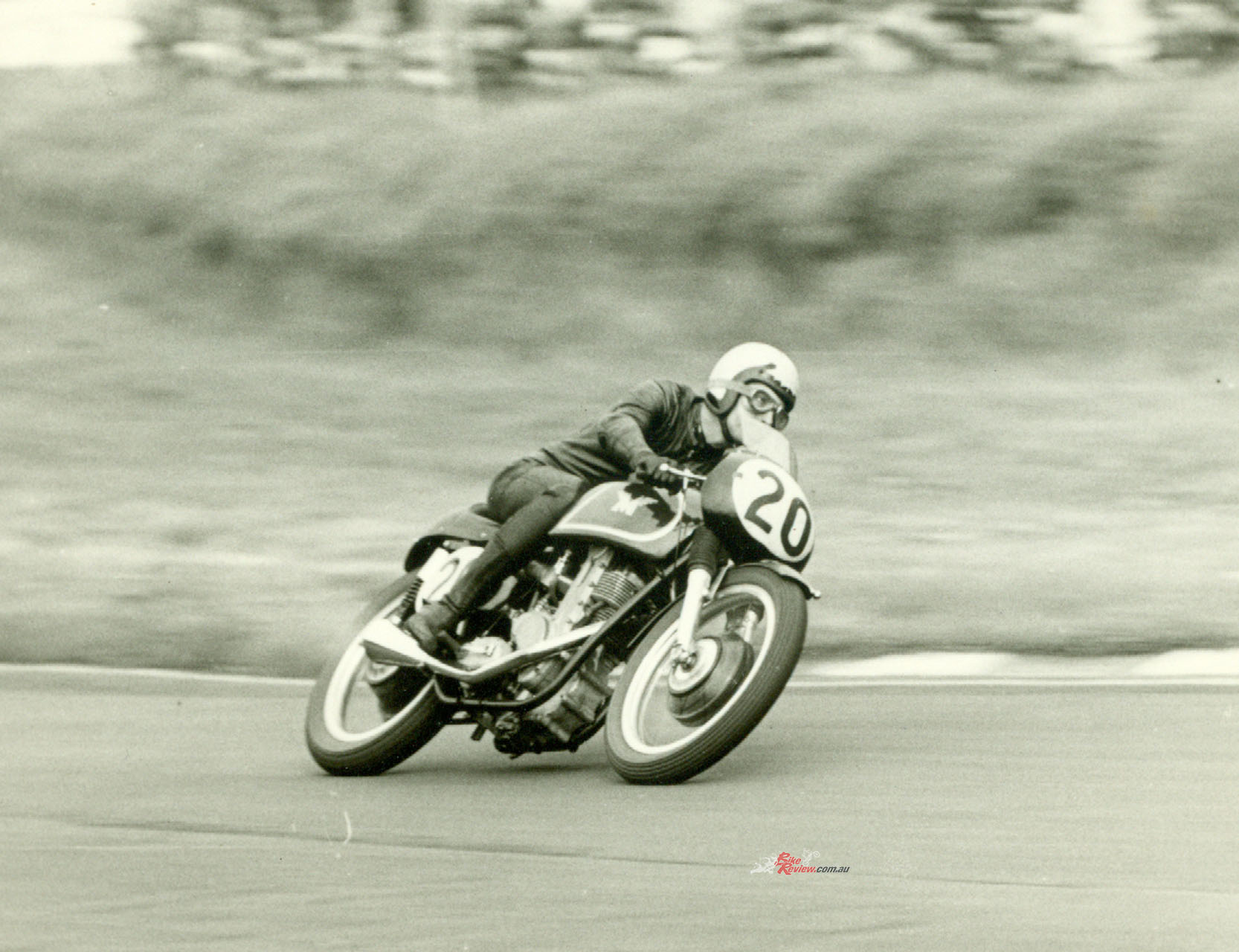

Mike on his new Manx Norton at Harewood Airfield in 1957. The bike took him to Expert level as a regular winner.

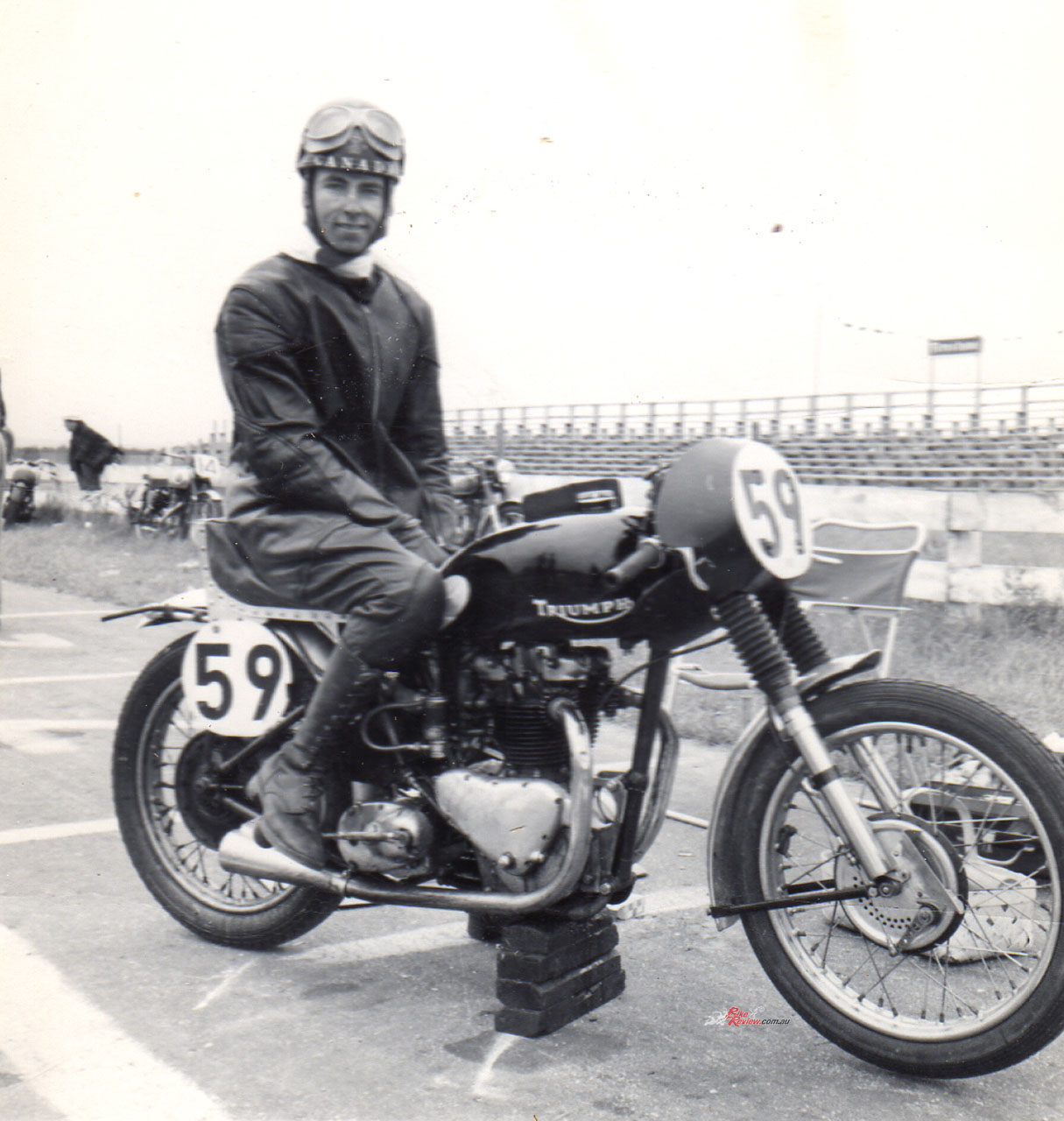

In 1955, Duff raced as a Junior rider on makeshift airfield racetracks, before progressing to Senior status in 1956. The following year, he bought a new 500cc Manx Norton racebike which took him to Expert level in 1958 as a regular race-winner. But his main intent was to pursue a road-racing career in Europe, so in in April 1960, aged just 20, he set sail for England from Montreal, having already shipped the Norton back to the British factory where it had been built.

“His main intent was to pursue a road-racing career in Europe, so in in April 1960, aged just 20, he set sail for England”…

After arriving in Liverpool he headed straight for the Norton factory in Birmingham to pick up his bike, duly fettled to 1960 spec by the factory race shop. Six weeks later he rode it in that year’s Isle of Man Senior TT, but DNF’d with a broken valve spring on lap 1. Duff then spent the rest of the year getting established as a rare Canadian among the plethora of Commonwealth riders from Australia, NZ and Southern Africa honing their skills in British short circuit racing in preparation for joining the Continental Circus, and trying to obtain entries in World Championship GPs.

One of those was Kiwi Hugh Anderson, a former coal miner who’d wound up riding for Kent-based tuner Tom Arter aboard his AJS and Matchless bikes, run with backdoor support from the AMC factory’s race department in nearby Plumstead. Hugh recommended Duff as his teammate aboard an Arter-run 650 twin, an AJS Model 31 CSR run prepared by the factory for the annual Thruxton 500-Miler for Production bikes.

This was the most important race in the calendar for most manufacturers, as a means of promoting the worth of their roadbike models. “Hugh and I did really well on the Ajay,” said Duff. “We were two laps in front of everyone else before suffering some magneto problems Tom quickly fixed, so we retook the lead. But about halfway through the race the front brake totally gave up – the cable fell out, we’d adjusted it so far. So we were just using the rear one, and that only lasted a few laps, so we literally had no brakes whatsoever for the last two hours, and finished well down in the end.” But his card had been marked, and when Hugh Anderson got a ride with the works Suzuki team for 1962, Mike Duff replaced him as Tom Arter’s rider.

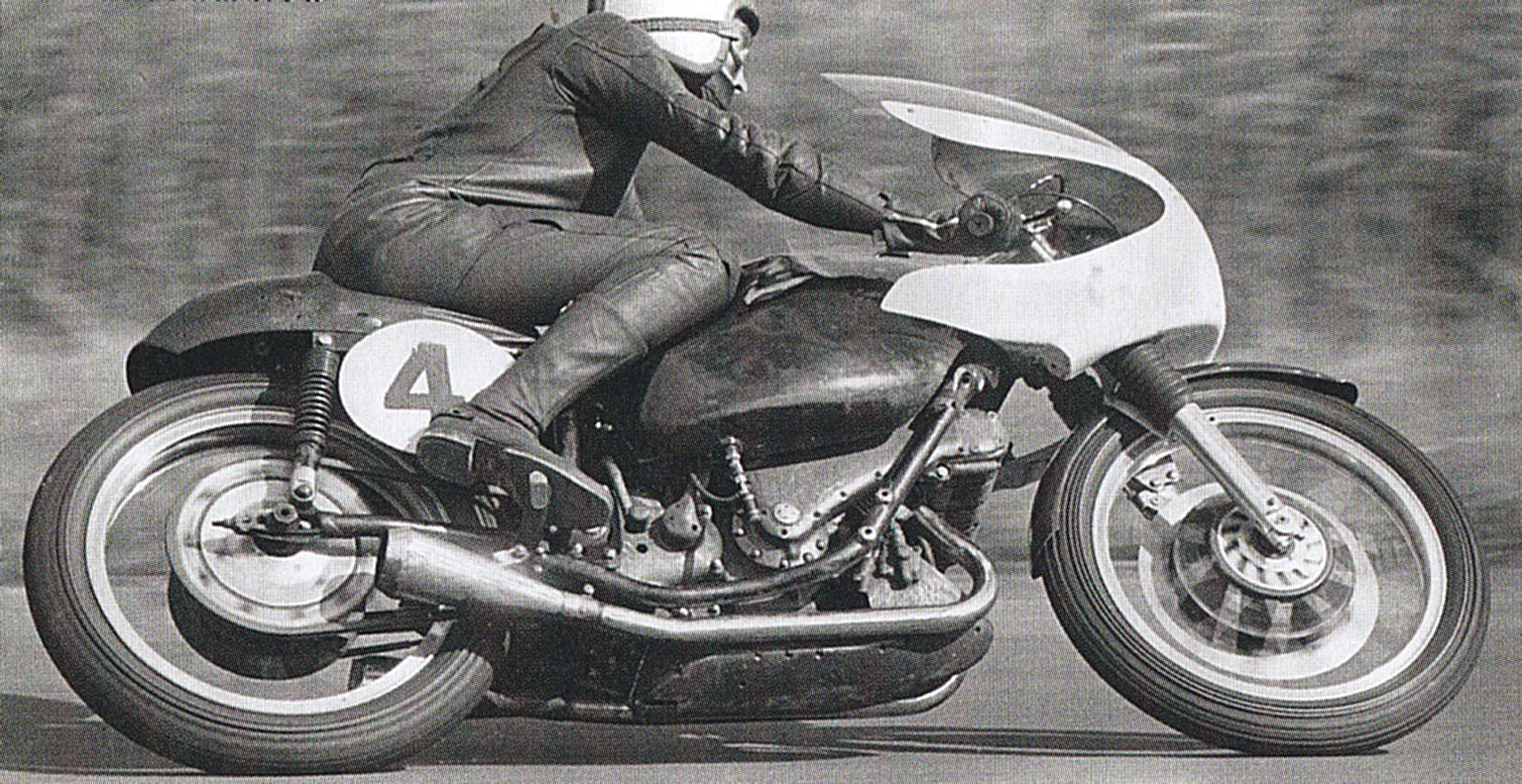

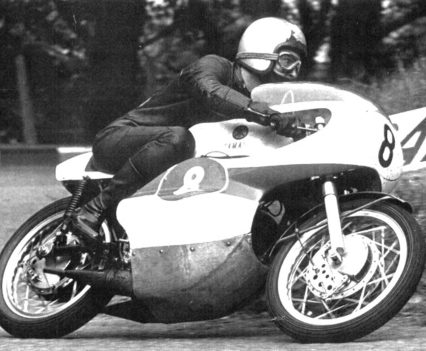

This was the Canadian’s ticket to the big time, as he became a regular contender for top honours both in the UK and Europe aboard Tom Arter’s fast, reliable 350cc AJS 7R and 500cc Matchless G50 machinery. This came after turning down Geoff Duke’s offer to ride the Gilera 500cc four-cylinder GP racer in 1963, out of respect for Arter – an example of Duff’s rare propriety among racers.

That year Mike finished 6th in the 500GP World Championship aboard the Arter G50, after earning his first GP rostrum with third in Finland, and fourth place in the Senior TT.

That year Mike finished 6th in the 500GP World Championship aboard the Arter G50, after earning his first GP rostrum with third in Finland, and fourth place in the Senior TT. In 1964 he went better still in the 350GP World series, winding up third in the final points table on the Arter-tuned Surtees 7R, a lightweight special concocted by John Surtees himself which he’d disposed of when he started car racing. He also finished fourth in the 500GP World Championship, with a pair of second places in the DDR and Finland.

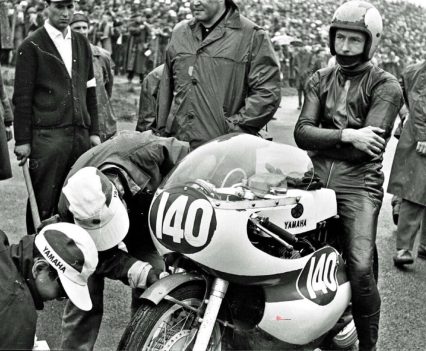

But this was also the year that the Canadian became the first rider from North America to win a Grand Prix, when he won the 250cc Belgian GP at Spa. This was only his second race for the factory Yamaha team, which had recruited him mid-season to support team leader Phil Read in his successful campaign to defeat the might of Honda in the 250GP class. Mike Duff was riding at the top of his form, regularly completing three gruelling hour-plus GP races in a single day on contrasting bikes – a pair of 350/500cc four-stroke singles, and a razor-edge rotary-valve 250 two-stroke twin which, with a top speed of 155mph, was the fastest of the three.

The first rider from North America to win a Grand Prix, when he won the 250cc Belgian GP at Spa…

He finished fourth in the final 250GP points table despite missing the first four rounds, but in 1965 he was second in the 250GP World series to teammate Phil Read, with nine podium finishes including another victory in Finland, and he also finished third in the Senior TT on the Arter Matchless.

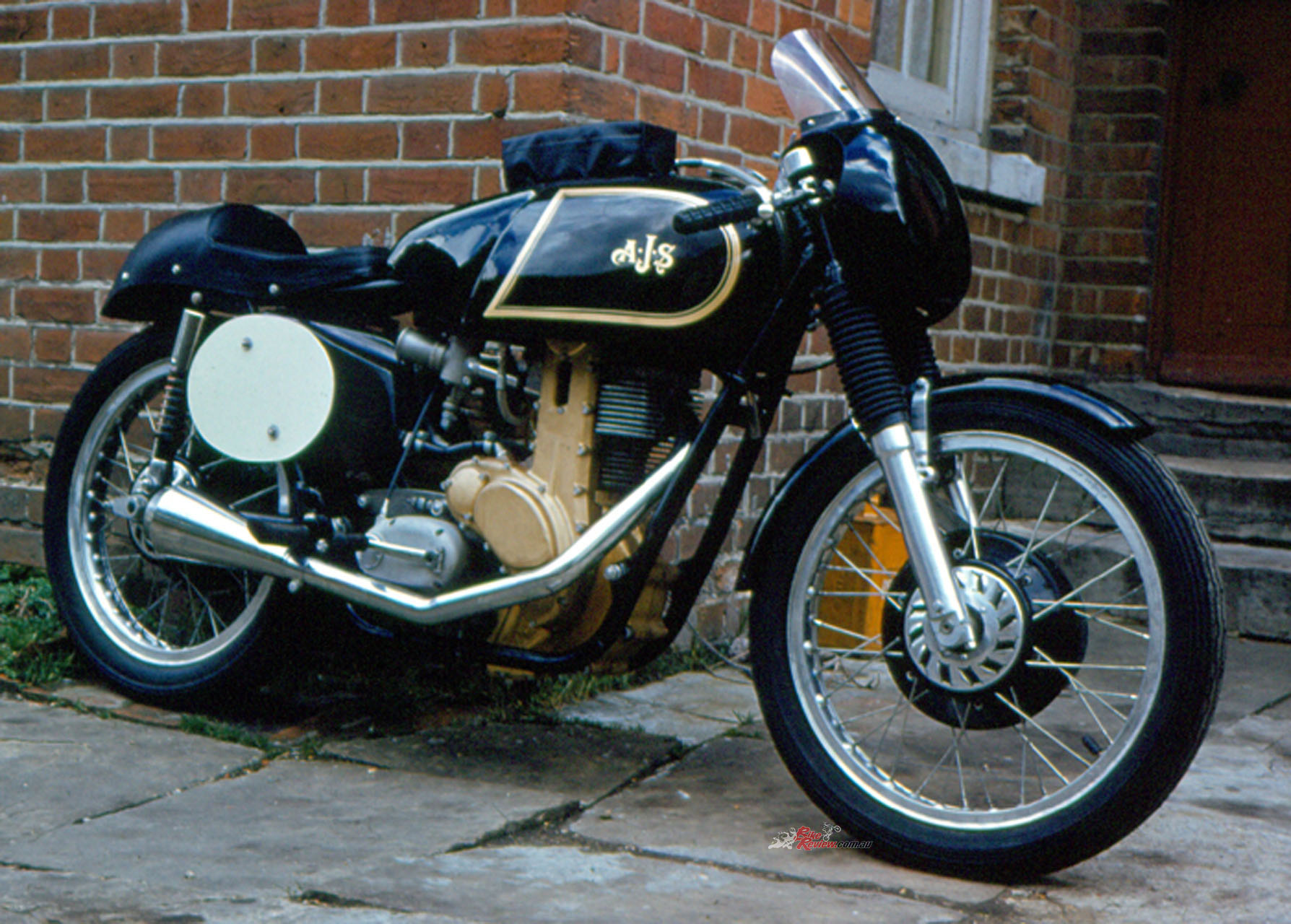

However, in 1963 the Duff/Arter duo had uncovered one of the ultra-rare AJS 500cc Porcupine parallel-twins built in the Plumstead factory, on the earlier E90 version of which Les Graham had won the first ever 500cc World Championship in 1949. Michelle Duff told me how this happened. “In 1964 I and my Dad took the crankshaft from my G50 to the AMC race shop to have a new crankpin put in. And as we walked up the little lane to the race shop, there was an AJS E95 Porcupine stood out uncovered in the rain, the later version with the pannier-tank layout. I thought, ‘A superb bike like this shouldn’t be left out here to get wet,’ so I went to see Jack Williams, the race manager for AMC, who was working on an engine on a test dyno.

“I said ‘Jack, can we take the Porcupine down to Tom’s, and put it on show?’ And he said, ‘What? What’d you say? Yes, go ahead, go for it.’ So we grabbed the Porcupine and threw it in the back of my van. We drove it to Tom Arter’s workshop, not to a showroom, and took the cylinder heads off to confirm that it was complete – and it was! We sent the magneto off to Lucas to see if it worked OK, and it came back just fine. So we put it all back together, and kind of guessed at ignition timing and valve timing – and it was a Tuesday night, starting to get dark.

“So we went up the road from Tom’s house, a dirt gravel road, and young Tommy, his son, was there with us. We put some petrol in the tank, and pulled it back on compression. I sat on the bike, and Tom and his son pushed it and took, I don’t know, four steps and I let the clutch out. And it fired instantly – it hadn’t run for ten years, and it fired up at once, and did it ever sound sweet, a big twin-cylinder engine like that. And I looked at Tom, and Tom looked at me, and we both said – ‘Brands Hatch tomorrow morning!”

“Every week, Wednesday morning was open practice for bikes at Brands, and we arrived right at the crack of dawn. I did just half a dozen laps on the Porc as soon as the track opened at 9am, then we put it back in the van and disappeared back to Arter’s. But next week in MCN there was a photograph of me riding round Brands Hatch on the Porcupine! And that same day before lunch, Tom got a phone call from the MD of AMC wanting to know what’s going on with their bike.

“So Tom put his suit and tie on, and brushed his hair – it wasn’t often that he did that! – and went up to Plumstead to see them. But he came back late that afternoon with a big grin on his face, and said, not to worry, it’s ours. He’d bought everything left in the race shop for a Porcupine. There was a complete spare engine, and a large pile of spare parts, though a lot of it was just raw castings that hadn’t been machined yet. And one engine had a built up crank, whereas the other had a solid crank, with split rods. I’m not sure if I should say this, but he bought the whole thing for £3,000!”

The saga of the Duff/Arter Porcupine Affair is a story in its own right, but suffice to say that after running a strong second in the Belgian GP at Spa, on a ten year-old bike, about two thirds of the way through it developed an engine vibration, and because it was so rare, Mike stopped at the pits, only to discover it was a trivial broken spark plug electrode. “The Porc was incredibly fast, about midway between the best Brit singles and Hailwood’s 500 MV-4,” said Duff. “It was a blast to ride, but we stopped because it was simply too valuable, and we had an obvious lack of replacement parts should anything break beyond repair.”

But Mike Duff’s racing career then took a downward turn in 1966. “I had a bad accident testing the new V4 prototype 250 Yamaha at the Suzuka Circuit in Japan at the end of the 1965 season, where I pushed my left leg three inches through my pelvis, and it took me a long while to get over that,” she said. A ten-week stay in hospital in Japan left him in danger of losing movement in his left leg. But after insisting he be repatriated to Canada, Duff had an early hip replacement procedure in Toronto, which after arduous physiotherapy resulted in his being able to walk again, and in due course, to ride a motorcycle.

He proved his ability to do so in public, by racing his old 1960-spec Manx Norton which his father had ‘bought’ from him in a Canadian National at Harewood, winning all three races he started. Nevertheless, Mike Duff’s injuries caused him major problems for the rest of his career, though his return to racing in 1966 was the subject of a National Film Board of Canada documentary produced by Robin Spry, entitled Ride For Your Life. The 11-minute movie was shown in cinemas across Canada, and in due course distributed in 16mm form to most Canadian schools. Check it out in full here, or watch the above YouTube video…

Two days after the Harewood race, Mike Duff returned to England. “Yamaha had promised that if I got back to racing form when I returned to Europe, I would be back on the team. So they lent me a little 125 twin to race at the Dutch TT in June, where I’d won the 125cc Dutch TT the year before, in ’65. But I was in really rough shape, physically and emotionally. I was making so many mistakes around the race course, rushing into corners too fast or braking too early, because I just wasn’t in the right temperament to be in Grand Prix racing.”

Despite that, in displaying huge bravery Duff finished sixth in his 125cc comeback race, so was restored to Yamaha’s 250GP team for next race in Spa, where he finished fifth – ahead of Bill Ivy, who was being touted as his replacement. He followed that up with a return to the rostrum in the DDR, third behind teammate Read, but ahead of Stuart Graham on a fast Honda six. Fourth at Brno seemed to indicate he was back on form – but it was at the cost of constant pain from his Suzuka injury.

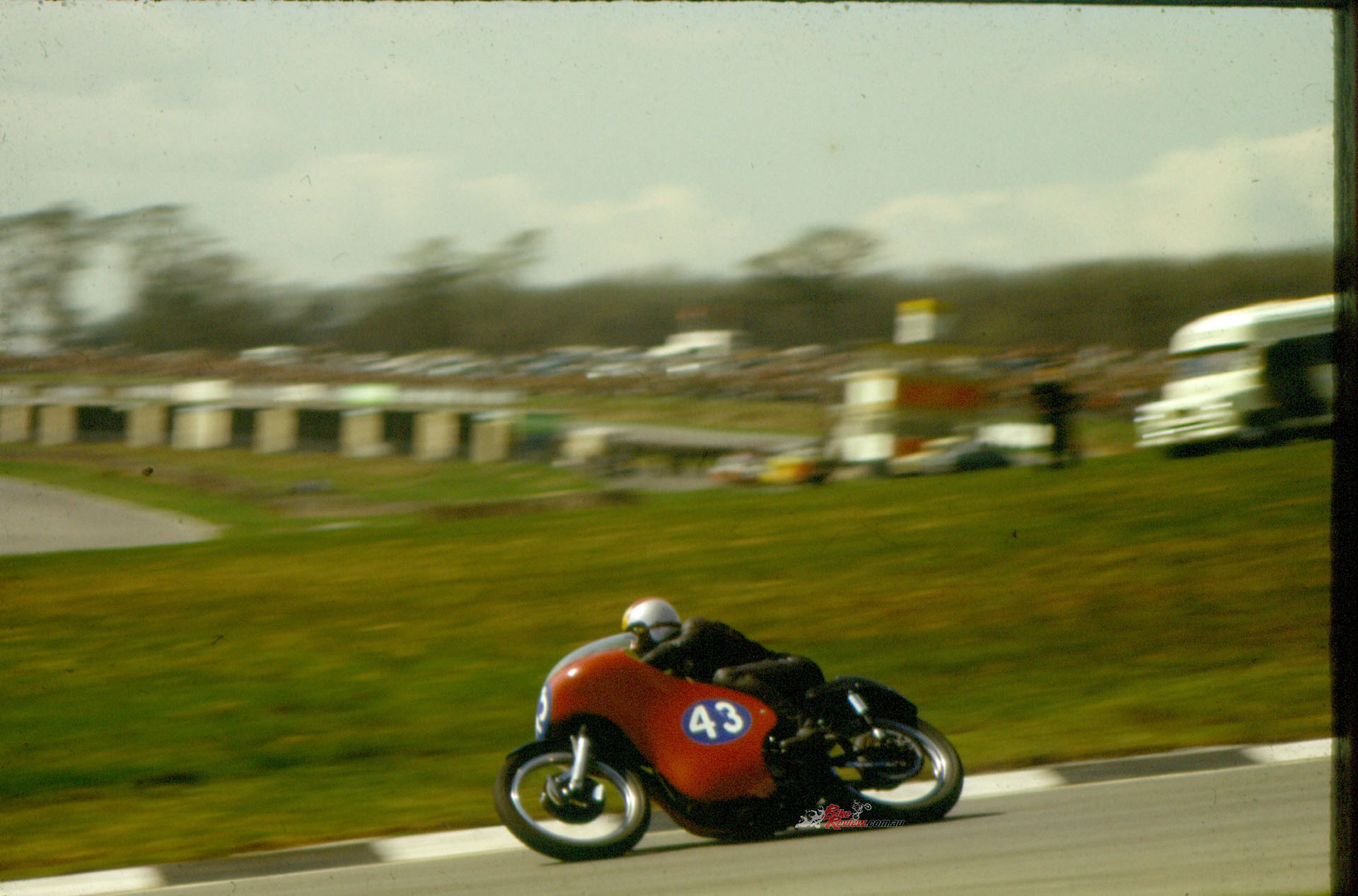

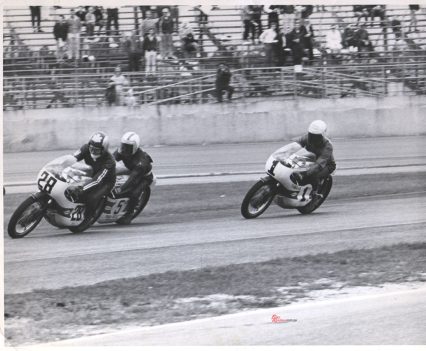

1966, Mallory Park, Mike Duff leads Bill Ivy over the finish line on identical RD56 Yamahas, finishing second to Hailwood’s Honda Six.

“I was racing on adrenaline, and I went back to racing just to get it out of my system,” Duff explained. “I could barely bump start a four-stroke single at the start of races, though a two-stroke was easier.” Proof that he was back to winning ways came with victory in the Hutchinson 100 Brands Hatch meeting in August, where he passed teammate Phil Read on the last lap to score a deeply satisfying win. He repeated the achievement at the Mallory Park Race of the Year, this time overtaking his replacement in the Yamaha GP team, Bill Ivy, on the final lap.

But it wasn’t enough to convince Yamaha they should keep him on board, so for 1967 Mike Duff returned to life as a privateer, racing bikes provided by the ever-faithful Tom Arter. But a foot injury sustained treading on broken glass in the Sachsenring paddock showers left him barely able to walk. At the end of a season to forget, he sold up his equipment and returned to Canada with his two children, separating from his Finnish wife Kriss whom he’d married in May 1962: he had a son with her the same year, and a daughter two years later.

Nevertheless, as Canada’s most illustrious GP rider he simply had to be on the grid for the one-off 500cc Canadian GP, held at Mosport in September 1967 to mark Canada’s 100th birthday as a nation. Tom Arter sent over one of his bikes for Duff to ride, but he had to start from the back row of the grid with a pusher because of the problems with his leg. “There were 45 starters, so I had to ride really hard to thread my way through the field, as well as taking care because it had started to drizzle. But I finally got into third place behind Hailwood and Agostini, and for me it was as good as a victory in a 40-lap, 73-minute race that seemed to go one for ever. It was my last GP rostrum – but maybe the one that gave me most satisfaction!”

Mike Duff’s final GP ride, third in the Canadian 500GP. As it turns out, Michelle said it was one of her most satisfying.

One in which he had an unexpected advantage. “For some reason, the Arter G50 was fitted with Goodyear tyres, and everybody else was running Dunlops, which back then weren’t very good in the wet – they’d let go without warning, whereas on the Goodyear tyres, you could lean them over and get them creeping a bit, lean a bit farther, they would skate some more and you would know, that’s enough. It was very fortuitous.”

That final podium finish on home ground in his last-ever GP race marked the end of Mike Duff’s international racing career, during which he’d started 58 GP races, with 24 rostrum finishes including three victories, and just ten DNFs. But he continued competing in the Canadian National championships, and finally retired from racing in 1969 after making a clean sweep of that year’s Canadian titles, and finishing third in the Daytona 200 and fifth in the 250cc support race on the Fred Deeley Yamaha twins.

58 GP races, with 24 rostrum finishes including three victories, and just ten DNFs... But it was tiring for me, and ‘Michelle’ was really asserting herself in my life strongly at that point.”

In 1972 Deeley set Duff up with a Yamaha dealership in Brampton, Ont. “But declining sales in the overall bike market led to a crash in the industry,” said Mike. “With that, I closed the doors of the store in 1978, moved the machine shop equipment into my basement at home, and continued with cylinder-boring and crankshaft rebuilding work. But it was tiring for me, and ‘Michelle’ was really asserting herself in my life strongly at that point.”

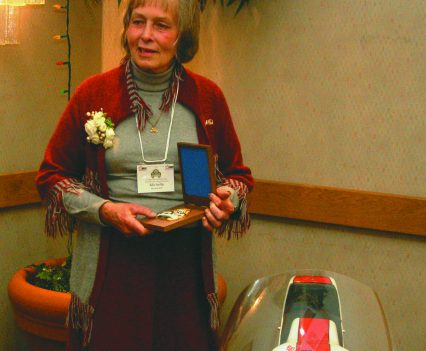

Michelle Duff at the Centennial TT in 2007. Mike Duff transitioned to Michelle in the mid-1980s. Michelle passed away on July 23, 2025, aged 85.

Indeed so. A quiet, polite and level-headed person who often seemed too thoughtful and kind to be a top level racer, after fathering three children from two marriages after years of self-doubt and frustration, Mike Duff later transitioned to Michelle in the mid-1980s. “I’d been born as a man, and I’d accepted I’d have to live my life as one.” Michelle told me.

“But ever since I’d reached the age of awareness I wanted to be female, all through puberty and adolescence, and all my adult life up to 1984. That’s when I finally decided to do something about it. I discussed it with my then wife {he’d remarried on his return to Canada, and fathered another son, Christopher] who was aware of my frustrations, and she agreed it was for the best – life wasn’t at all pleasant for her, and it had got really difficult living together under what amounted to a charade. So in 1984 I set up keeping house as a woman. Only one in four people born as men who do that are still following their chosen role a year later – but I did. I’ve never regretted it.”

She changed her name to Michelle Ann Duff, and in 1987 underwent gender reassignment surgery in Belgium. Michelle initially left her motorcycling life behind, and after retiring from her job as an Ontario civil servant, she left Toronto and moved to Nova Scotia, to live a quiet life with her beloved pets, augmenting her pension with work as a wildlife photographer. Michelle passed away on July 23, 2025, aged 85.

I’d known Mike Duff and his family in the early ‘80s, when they stayed in my house in London for a few days not long before he made his momentous change. We picked up our friendship again in 1998, when she returned to the motorcycle world by riding at the massive Centennial TT historic event at Assen. Nursing a broken leg myself, I lent her my Matchless G50 to ride in the 500GP class alongside the 250/350 Yamahas which event organiser Ferry Brouwer (once a mechanic in the works Yamaha GP team) had arranged for her. I thus witnessed firsthand how Michelle literally flowered as a person over the weekend. From shy and cautious at the very start, by Sunday evening her self-confidence had blossomed as she realised that most bike people were supremely indifferent to whatever path she chose to follow in terms of sexuality, or gender.

Mosport 50th Anniversary, Canadian Tire Motorsport Park. Michelle was reunited with her Canadian GP podium finishing Arter Matchless G50.

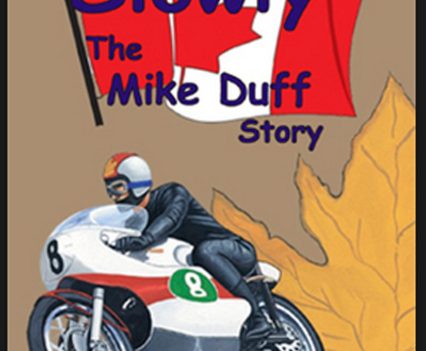

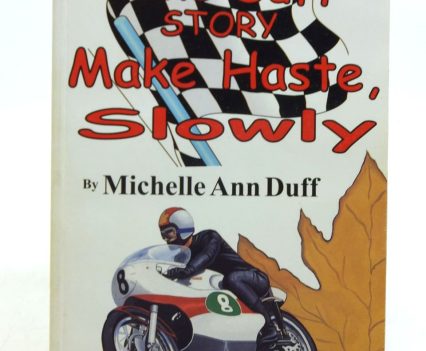

Indeed, it was that Assen experience which led Michelle Duff to write her self-published book Make Haste Slowly: The Mike Duff Story, her personal well-documented racing history. First published in 1999, a second edition was released in 2011, with over 5,000 copies sold in total, making it an official best-seller in Motorcycle publishing. She was inducted into the Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2007 in recognition of her years of racing at World Championship level, and was invited by Yamaha to ride a replica RA-05 250cc V4 at the 2007 Centenary TT Parade in the Isle of Man.

From time to time we’d meet up at various Historic bike events, most notably for the last time at the 2017 50th celebration of that unique Canadian GP at Mosport. There, for the live rides down memory lane Team Obsolete patron Robert Iannucci, who’s become the curator of all Tom Arter’s racing machinery, had assigned me the Surtees 7R special which Mike Duff had ridden to third place in the 1964 350GP World Championship alongside her 250GP-class Yamaha exploits, while Michelle was reunited with her Canadian GP podium finishing Arter Matchless G50.

But when she unexpectedly saw the Surtees Special there, her eyes moistened and she got rather emotional. So after a couple of token laps on the Arter G50, we swapped machines, and she spent the rest of the weekend on what she described as “my favourite bike – the best one I ever rode.” It was her swansong from on-track action – and a nice way to leave the racing stage for good.

Godspeed, Michelle.