Last month we featured Olivier Jacque's winning YZR250, this month it is the Yamaha's rival, Honda's 2000 NSR250. AC rides the Daijiro Kato machine... Photos: Koichi Ohtani, Kel Edge

Last month Sir Al brought us his 2000 YZR250 test. The same year, he rode the Honda that Yamaha beat. Improbable though seems, Honda went three seasons without winning GP racing’s 250cc title with their twin-crank NSR250 introduced in 1998. Read on…

The 2000 NSR250 was 102hp, 96kg and had a top speed over 265km/h. They don’t make them like that anymore.

But at the start of the Y2K season, it seemed this would be rectified, with Japanese rising star and former National 250 champion the late great Daijiro Kato joining HRC’s longtime 250GP contender Tohru Ukawa in an onslaught on the World title which, in the wake of Aprilia’s relegation to the also-rans after Valentino Rossi’s step up to the 500cc class, they were widely expected to win.

Read Sir Al’s previous racer tests including the 2000 Yamaha YZR250 here…

It didn’t turn out that way, though, for Honda had reckoned without Yamaha’s feat in transforming their YZR250 into the finest all-round quarter-litre GP racer of its generation, with two top riders in future World champion Olivier Jacque and runner-up Shinya Nakano targeted on the 2000 title from the very first round. Kato put up a vivid struggle, though, scoring points in all sixteen races and winning four of them (Ukawa won just two), finishing off the rostrum only six times all season en route to third place in the championship on his Italian-run Team Gresini bike.

Daijiro-san even had a mathematical chance of winning the championship going into the last race at Phillip Island but only if his two Yamaha rivals took each other out vying for the title. As we now know, that didn’t happen – just! So Honda would have to wait another year to prove the worth of the new technical direction in which they’d taken NSR250 development three years earlier in 1998.

“At one stage the NSR was delivering less power than Honda’s privateer RS250 kit bikes”…

That year had marked the debut of the all-new twin-crank works Honda NSR250, which gained just a solitary GP win in its maiden season, and at one stage the NSR was delivering less power than Honda’s privateer RS250 kit bikes! HRC engineers worked flat out to correct that situation for 1999, and succeeded so well that lead Honda rider Ukawa made a serious bid for the World title, only surrendering the points lead to the Rossifumi Roadshow two-thirds of the way through the season.

New cylinder heads, vertically-split crankcases, crankshaft, pistons, cylinder porting and exhaust pipes, as well as modifications to the twin 39mm Keihin flatslides with electronic powervalve for 2000.

But Ukawa still finished a fine second in the championship, repaying the hard work that HRC engineers had invested to bring the troubled new bike up to speed. At that stage, you had to feel sorry for Olivier Jacque, who’d switched teams from Honda to Yamaha, against the current tide of competitivity. Turned out to be a smart move in the end, though!

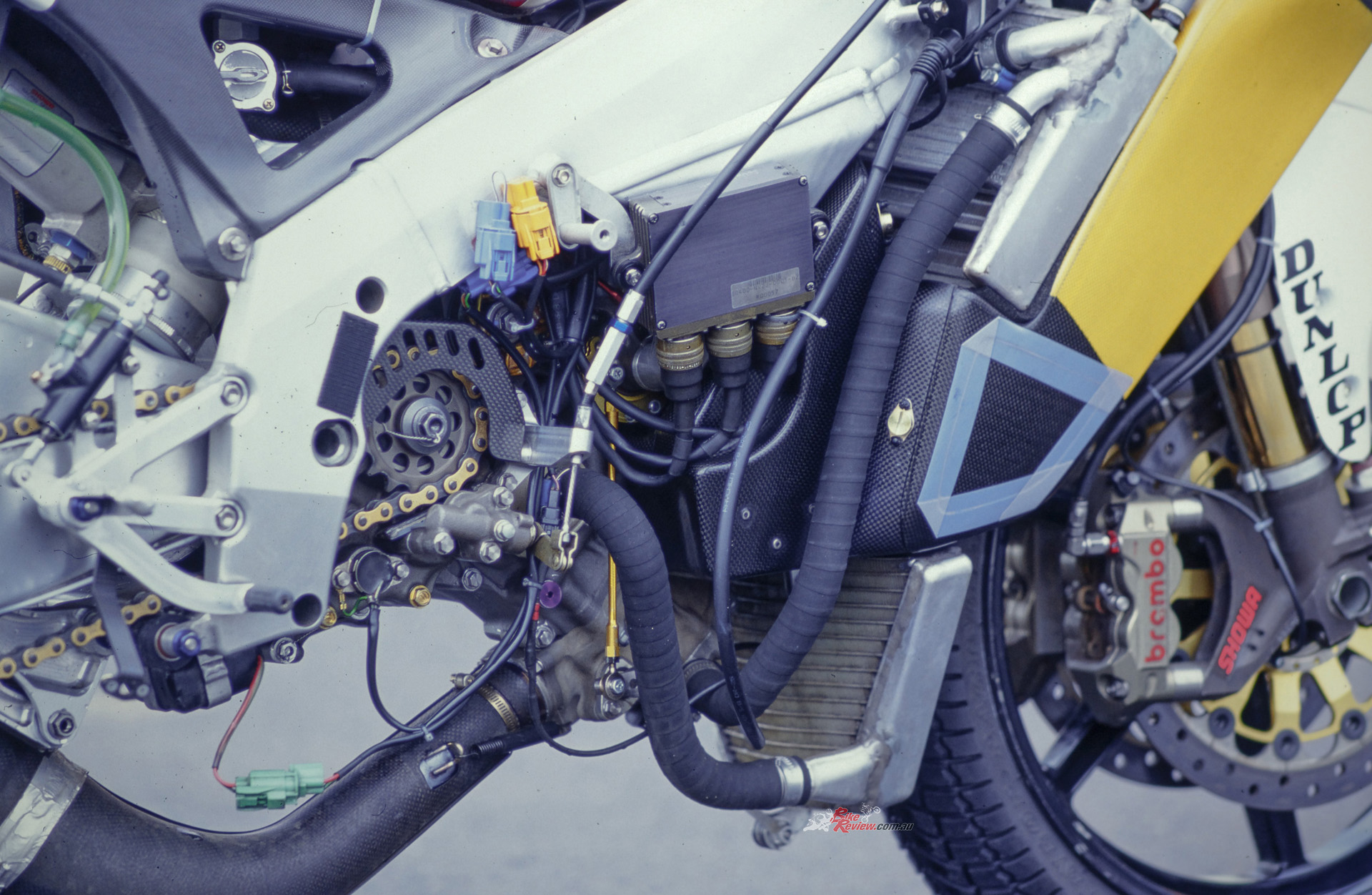

For despite completely revamping the NSR250 for 2000, Honda had to play second best once again in 2000, this time to their sternest Japanese rivals. In doing this, they didn’t exactly throw away the ’99-series NSR motor, but they did change almost every detail on the twin-crank 100° V-twin crankcase reed-valve engine in order to raise the ante in performance terms – new cylinder heads, vertically-split crankcases, crankshaft, pistons, cylinder porting and exhaust pipes, as well as modifications to the twin 39mm Keihin flatslides with electronic powervalves, one of which was fitted with a throttle position indicator governing ignition and RC-valve operation, both of which had a different curve than before.

HRC had to change almost every detail on the twin-crank 100° V-twin crankcase reed-valve engine in order to raise the ante in performance terms for the 2000 season.

The design of the carbon airbox had been altered, and so too was the reed-valve box in the crankcases, though reed design itself was unchanged. The result was a 3 per cent hike in peak power, which was now back over 100 bhp for the first time since the introduction of unleaded fuel, thus now overtaking the Aprilia in top speed, while also delivering an increase in midrange torque, with a smoother transition into the peak power band between 10,000 and 11,000 rpm.

This especially helped Daijiro Kato, who in contrast to Tohru Ukawa’s classical 250GP riding style utilising a high turn speed, had a point-’n’-turn style more like a 500GP rider, so tended to employ more midrange and lowdown power than his fellow Honda rival (no, never teammates!), with a consequent emphasis on acceleration.

“A 3 per cent hike in peak power, which was now back over 100 bhp for the first time since the introduction of unleaded fuel”…

THE RIDE

Riding Kato’s 2000 bike on a damp, dark but drying Motegi track underlined the improvement in power that Honda engineers had extracted from their NSR250 motor that season, compared to when I’d tested Ukawa’s 1999 motorcycle twelve months earlier at the same circuit. In comparison with this, and with OJ’s World title-winning Yamaha I was to sample just two weeks later in Jerez, the Kato NSR250 definitely had a more vivid burst of acceleration above 9,000 rpm, and got really strong once you raised the needle on the analogue tacho above 11,000 revs.

Once I’d straightened up and started flying right on the grippy Michelin soft-compound rain tyres, the little 250 Honda would pull a determined second-gear wheelie every lap out of the last turn at Motegi. While rev-hound Ukawa never allowed the motor to run below the five-figure mark, Kato rode the torque curve of the little bike more than his fellow-Honda rider, taking full advantage of the increased midrange punch.

Once I’d straightened up and started flying right on the grippy Michelin soft-compound rain tyres, the little 250 Honda would pull a determined second-gear wheelie every lap out of the last turn at Motegi. While rev-hound Ukawa never allowed the motor to run below the five-figure mark, Kato rode the torque curve of the little bike more than his fellow-Honda rider, taking full advantage of the increased midrange punch.

So the Honda would now pull hard and clean from as low as 8,000rpm out of a tight turn like Motegi’s top hairpin, building power very fast all the way to the 13,300rpm peak, where 102 bhp was now on tap – actually, a little more than the old single-crank NSR250 ever gave when running on leaded race gas. By now, the red shifter light on the dash had flashed brightly at you at 13,000rpm, telling you to tap the wide-open powershifter gearshift to send the tacho needle back down to 11,000 rpm.

There was a healthy 1,200rpm of overrev if you needed it, though, allowing you to run the 54 x 54.5 mm engine as high as 14,500rpm before the power fell off, to save a couple of gearchanges – like in the short straight between the last two turns leading onto Motegi’s main straight – or to gain track position. There wasn’t such a narrow power band as I’d expected from a hundred-horsepower 250, so not as much need to use the sweet-action gearbox very hard to make sure the engine’s always revving up high.

There was a healthy 1,200rpm of overrev if you needed it, though, allowing you to run the 54 x 54.5 mm engine as high as 14,500rpm before the power fell off, to save a couple of gearchanges – like in the short straight between the last two turns leading onto Motegi’s main straight – or to gain track position. There wasn’t such a narrow power band as I’d expected from a hundred-horsepower 250, so not as much need to use the sweet-action gearbox very hard to make sure the engine’s always revving up high.

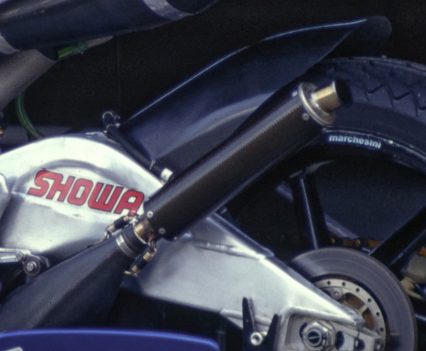

Honda paid equal attention to revamping the twin-spar aluminium NSR250 chassis for the Y2K season, while retaining the more traditional format introduced the previous year after the failure of 1998’s so-called ‘pivotless’ design – but still with the all-new, heavily braced swingarm mounted in the engine crankcases. However, the design of the side spars as well as the method of construction were both altered, in pursuit of HRC’s policy of controlled flex.

This was aimed at, according to HRC engineers, delivering an easier turn-in thanks to more feedback from the frame, and better drive because of a more forgiving chassis response. However, admittedly on a damp track, the result didn’t seem to have the balanced feel of the Jacque Yamaha, which combined nimbleness with stability, and felt both agile and planted at the same time.

This was aimed at, according to HRC engineers, delivering an easier turn-in thanks to more feedback from the frame, and better drive because of a more forgiving chassis response. However, admittedly on a damp track, the result didn’t seem to have the balanced feel of the Jacque Yamaha, which combined nimbleness with stability, and felt both agile and planted at the same time.

By contrast, the Honda felt quite a bit more nervous, and less confidence-inspiring in terms of feedback from the suspension – all the more vital when you’re trying to get the tyres to talk to you when running on a slippery surface. That wasn’t helped by the Honda’s build – as in the past, it felt considerably smaller overall than the Yamaha, despite the redesigned and more aerodynamic bodywork for 2000, and was almost as toy-like as a 125 by comparison.

That was despite the broader flanks to the front of the fairing and screen, which was very low and didn’t seem to give as much protection as the Yamaha’s distinctive streamlining – certainly not to my un-250 like stature. The result was a bike built for a much smaller rider, which only he would feel comfortable in. Fine – but in the search for the fast handling that a smaller, quick-steering bike delivers, I wonder if Honda hadn’t gone too far, and sacrificed that sense of security round the faster turns on which the undeniable performance of the NSR250’s wide-angle V-twin engine laid such strong emphasis.

That was despite the broader flanks to the front of the fairing and screen, which was very low and didn’t seem to give as much protection as the Yamaha’s distinctive streamlining – certainly not to my un-250 like stature. The result was a bike built for a much smaller rider, which only he would feel comfortable in. Fine – but in the search for the fast handling that a smaller, quick-steering bike delivers, I wonder if Honda hadn’t gone too far, and sacrificed that sense of security round the faster turns on which the undeniable performance of the NSR250’s wide-angle V-twin engine laid such strong emphasis.

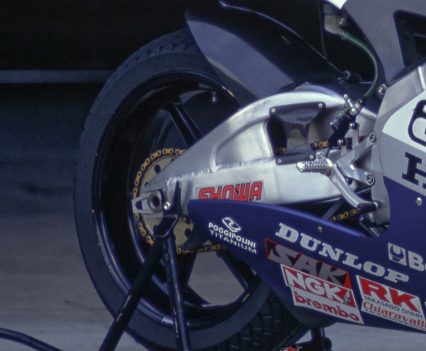

The damp track meant that the bigger 290mm Mitsubishi carbon discs which Kato preferred using (compared to Ukawa’s option for the smaller 255mm black rotors – another illustration of the different hardware their contrasting riding styles require) were substituted for my ride by Brembo metal discs – but even in the damp there was quite a lot of front end dive under hard braking into a slower turn, like Turn 2 at Motegi.

Kato used softer settings on the 43mm SHOWA forks than Ukawa, not only since he was lighter than him, but also because he preferred a smoother, more compliant response – and perhaps for that reason I noticed the Honda still understeered a little exiting a faster turn under power, just like last year’s bike: possibly the rear end was set too soft for my extra weight, kicking the forks out slightly. Easily fixed, especially at my sort of lap speeds in the damp, by pulling it back on line – but I wonder just how good an overall handling package the Honda was in 2000, compared to that brilliantly evolved Yamaha?

That seemed to deliver the best of both worlds, by combining more than adequate engine performance – not as potent as the class-leading Honda, but quite good enough to win races convincingly – with superlative handling. For Honda, the 2000 250GP season was a case of – close, but no cigar….

That seemed to deliver the best of both worlds, by combining more than adequate engine performance – not as potent as the class-leading Honda, but quite good enough to win races convincingly – with superlative handling. For Honda, the 2000 250GP season was a case of – close, but no cigar….

2001 didn’t answer that question, for with Yamaha’s factory 250GP effort sidelined in favour of an emphasis on four-stroke GP1 [aka MotoGP] development, and the Y2K title-winning bikes entrusted to a Malaysian privateer team, there were only two manufacturers represented in the class, Aprilia and Honda. But with Ukawa moving up to the 500GP class, it would be Kato who’d shoulder the burden of spearheading Honda’s attempt to finally win back that elusive 250GP World title in 2001, with an updated version of his Y2K NSR250. History tells us he did just that, winning 11 of the 16 races on that bike, ahead of a phalanx of five Aprilias with various degrees of factory support. The reworked NSR250 Honda’s time had finally come….

2000 Honda Factory NSR250 GP Specifications

Engine: Liquid-cooled 100º V-twin crankcase reed-valve two-stroke with vertically split cases, two contrarotating crankshafts, electronic RC-exhaust valve, 54 x 54.5mm bore x stroke, 12.2:1 compression, digital CDI ignition, six-speed cassette gearbox, multi-plate dry clutch, twin 39mm Keihin flatslide carburettors with electronic powervalve and one carb fitted with a throttle position sensor governing ignition curve and RC-valve operation.

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar frame, fabricated aluminium swingarm, 1345mm wheelbase, variable head angle, fully adjustable 43mm SHOWA extruded aluminium forks, proling rising rate SHOWA rear suspension, dual 290mm Mitsubishi carbon rotors with four-piston Brembo calipers (f), 196mm HRC steel rotor with two-piston HRC caliper (r), Marchesini cast magnesium wheels – 3.50 x 17in, 5.50 x 17in, Dunlop KR106 120/60 – 17 front, KR108 170/55 – 17 rear tyres.

Performance: 102hp@13,300rpm at crank, 96kg with oil/water no fuel, top speed over 265km/h.

Owner: Honda Racing Corporation, Saitama, Japan