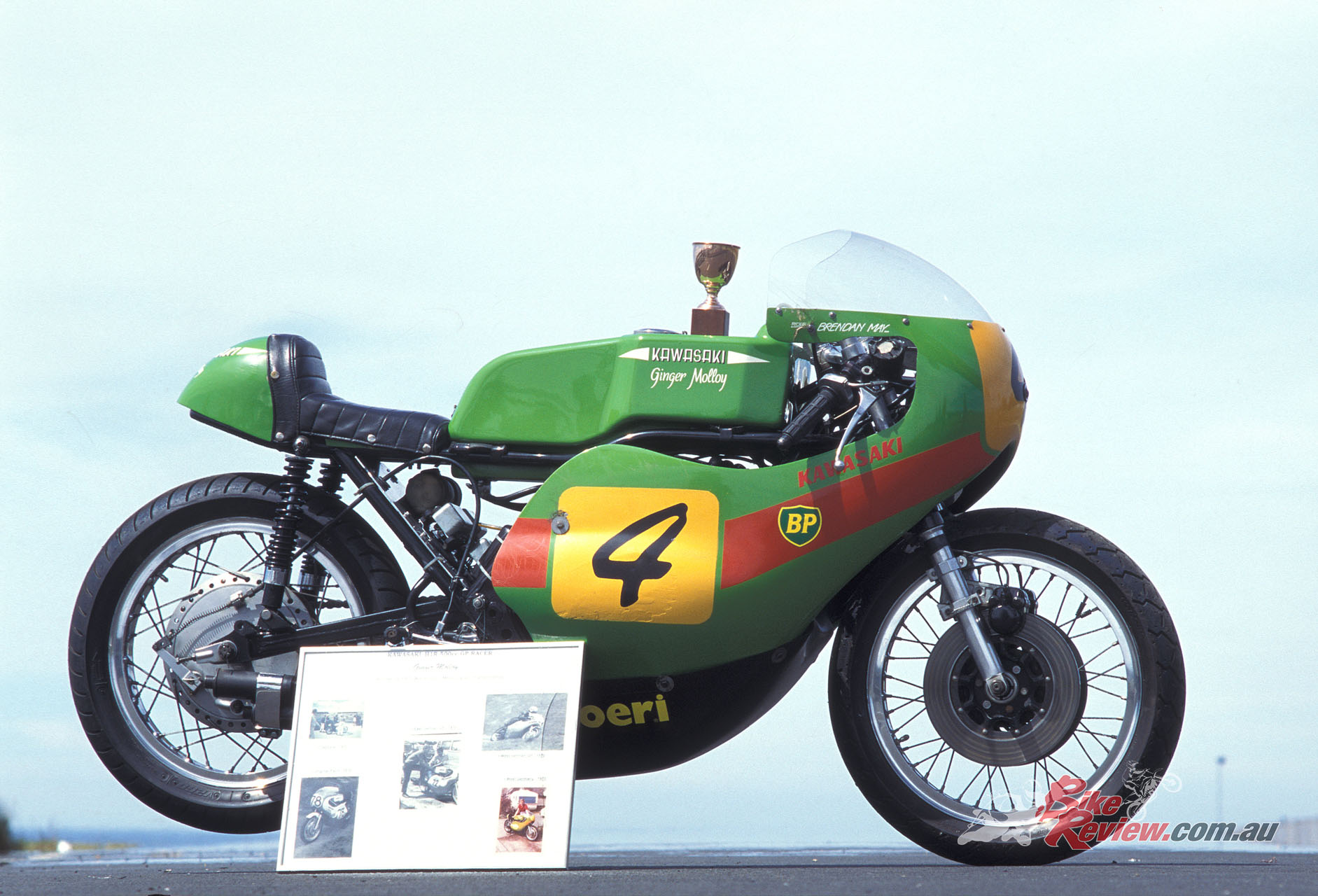

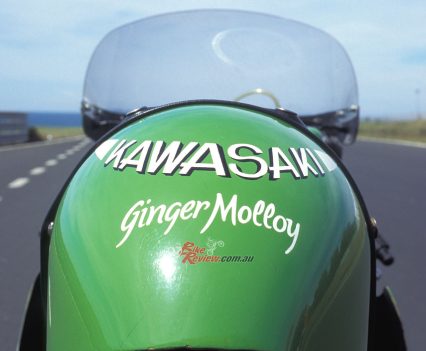

Ginger Molloy made Agostini sweat on his Kawasaki H1R before the Japanese brand pulled the plug on two-strokes. Cathcart gives us the complete history of this amazing bike...

Ironic, really. Despite creating the iconic H1R, alone out of the four Japanese manufacturers, Kawasaki firmly turned its back away from two-stroke GP racing at the end of 1982, in favour of exclusively concentrating its race efforts on the four-strokes it sold for the street.

It was the manufacturer of the Green Meanies which was responsible for building what is arguably the most significant motorcycle in the history of the 500GP class… the Kawasaki H1R.

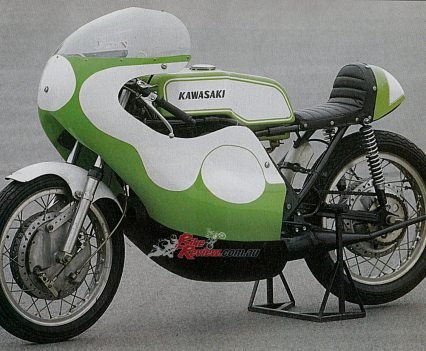

It was the manufacturer of the Green Meanies which was responsible for building what is arguably the most significant motorcycle in the history of the 500GP class, since it ushered in the modern era of competition technology when it made its debut on the World stage exactly 50 years ago in 1970 – the three-cylinder 500cc two-stroke Kawasaki H1R.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

Honda’s withdrawal from GP racing at the end of 1967 had left the 50cc and 125cc GP classes firmly under the control of its two-stroke rivals, while the FIM’s short-sighted ban on more than two cylinders would shortly do the same for the 250s, after Benelli’s swansong World title in 1969 courtesy of Kel Carruthers. The 350cc class was already awash with Yamaha two-strokes as the favoured mount of all but riders of the Italian multi-cylinder works racers, leaving just the blue riband 500cc category as the final fortress of four-stroke supremacy. But only because the Japanese hadn’t got round to developing a bike for it yet. But in 1970, they did.

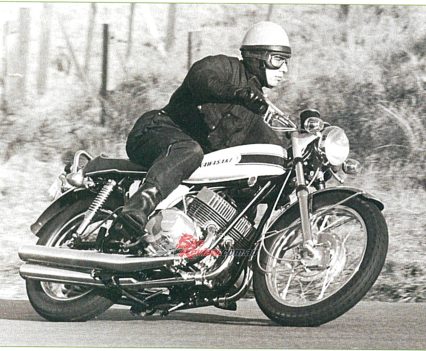

Kawasaki had already stunned the world in 1969 by launching the first large-capacity two-stroke streetbike of the modern era, and the 500cc H1 Mach III was Just Amazing – a true hooligan bike, the first headbanger’s hotrod. Inevitably, it swiftly ended up on the race tracks of the world, where it gained further street cred by being immediately competitive and surprisingly reliable, as well as numbingly fast by the four-stroke standards by the day – enough so, for example, to spring an upset victory in the 1969 Le Mans 1000km Endurance race, and to come within an ace of winning the Bol D’Or 24-hour marathon, finishing second, third and fourth after yielding the lead to the winning 750 Honda only in the final hours.

Read about our resto on a 1974 Kawasaki H1 here…

For a company whose greatest success on the track until then had been to win the World 125GP title with Dave Simmons riding its rotary-valve parallel-twin that same year, it was a short but inevitable step to develop the full-on 500GP production racer that the Mach III seemed destined to spawn. In doing so, Kawasaki altered the face of Grand Prix racing forever.

With the commercial success, was a short but inevitable step to develop the full-on 500GP production racer that the Mach III seemed destined to spawn. In doing so, Kawasaki altered the face of Grand Prix racing forever.

Unless your name was Giacomo Agostini, and you could parade to a series of unchallenged GP victories and World titles aboard Count Agusta’s MV four-stroke triples, if you raced in the 500cc GP class up until the end of 1969, you had to be satisfied with riding a Matchless G50 or Manx Norton based British single that was at least 40mph/60km/h slower than the MV. These bikes did have the benefit of being cheaper to run and easier to maintain than the Italian Paton and Linto twins, which were the privateer’s only other option.

Read Cathcart’s racer test here…

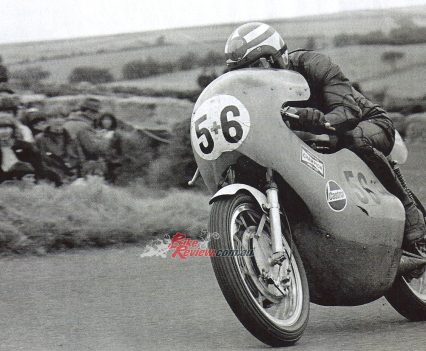

You did have a choice of racing a nominally bored 350 stroker, so the first time a two-stroke ever finished on the rostrum of a 500GP race was when New Zealander Ginger Molloy took his 360 Bultaco single to third place in the 1969 Spanish GP at Jarama – out of just seven finishers! Two-strokes weren’t an option – yet.

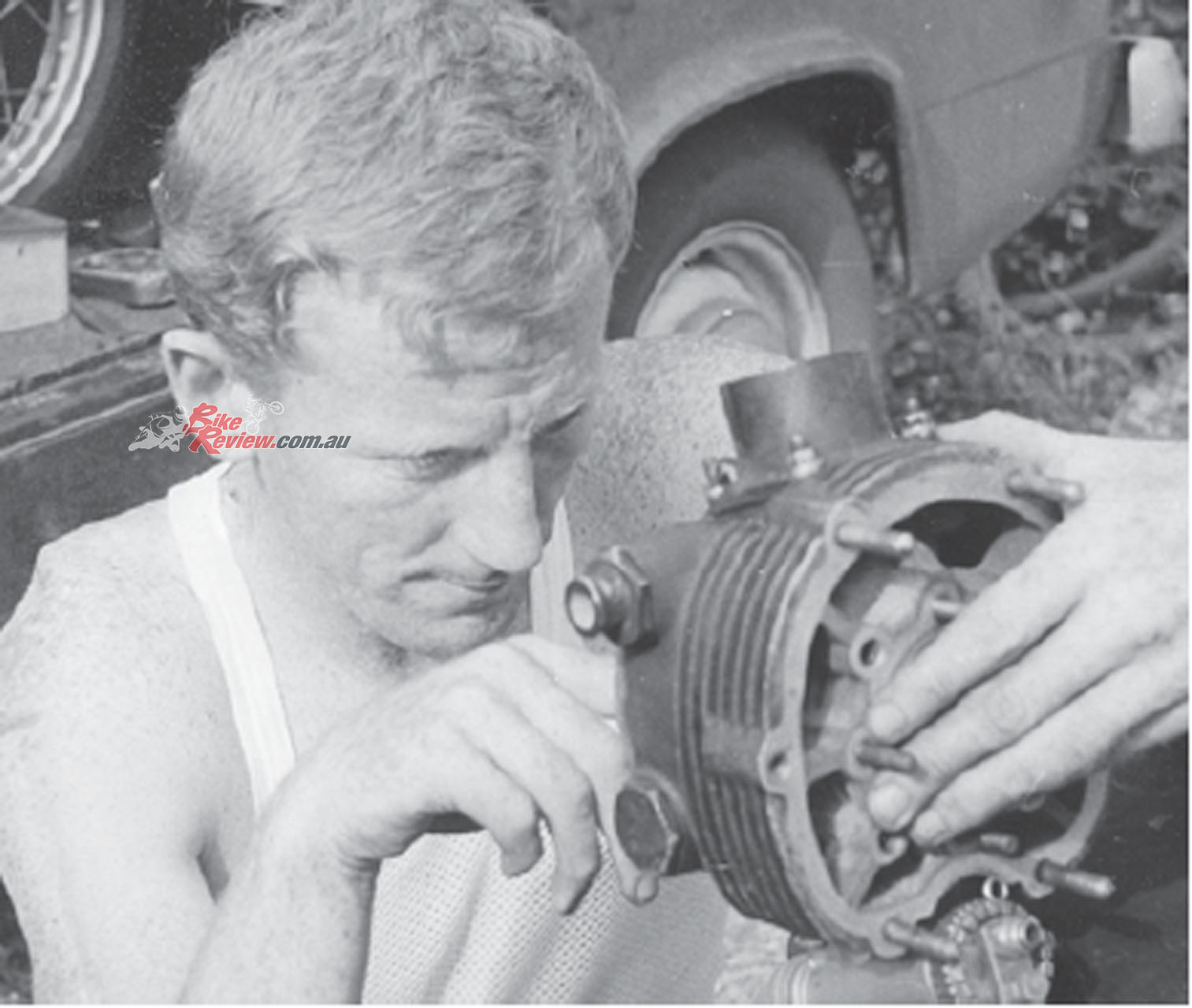

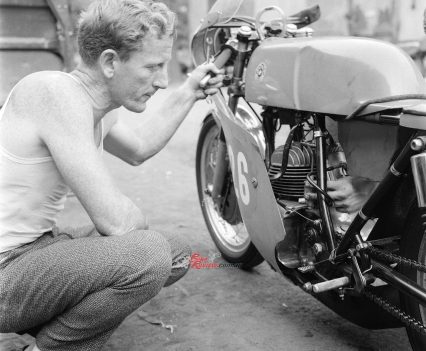

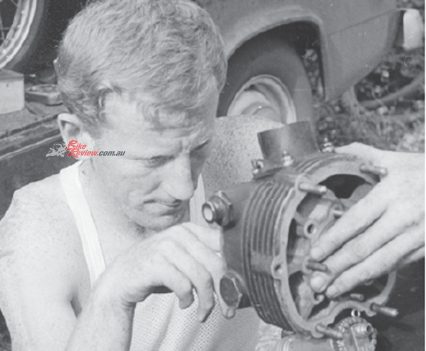

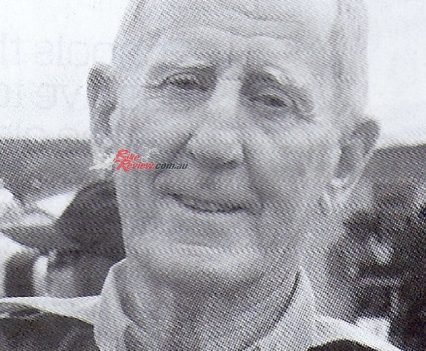

Ginger Molloy working on his Bultaco TSS cylinder. Back when you didn’t need to show up to a race weekend with a team transporter.

But a year later they were – and Molloy, who was his own mechanic and knew better than most how to prepare a fickle, seizure-prone two-stroke racer of the era, and to make it reliable as well as ride it properly, was the man who proved it. He did so by finishing runner-up to Ago’s MV Agusta in the 1970 500cc World Championship, in the debut season of Kawasaki’s H1R customer racer, the bike that in doing so changed the GP world forever.

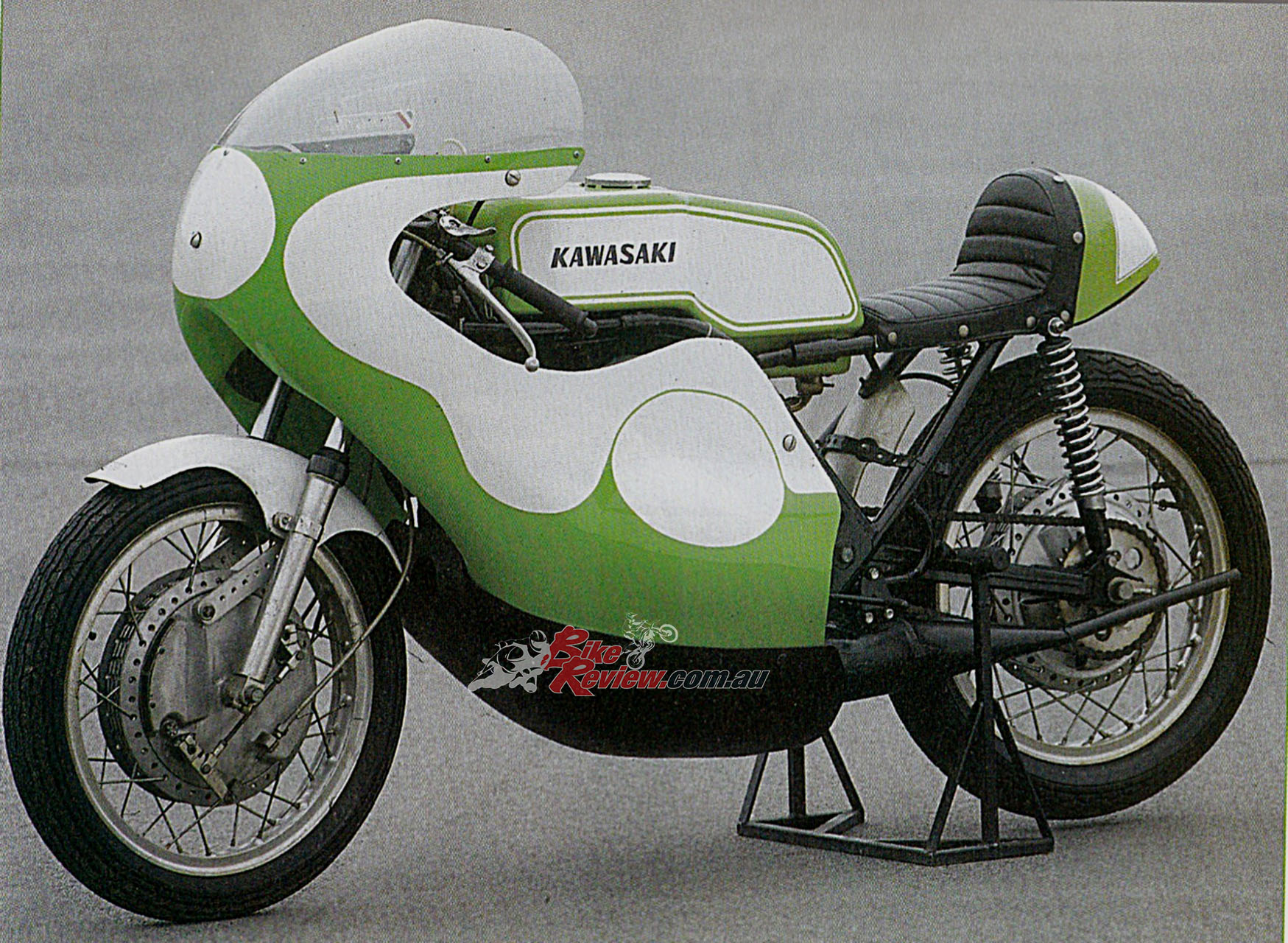

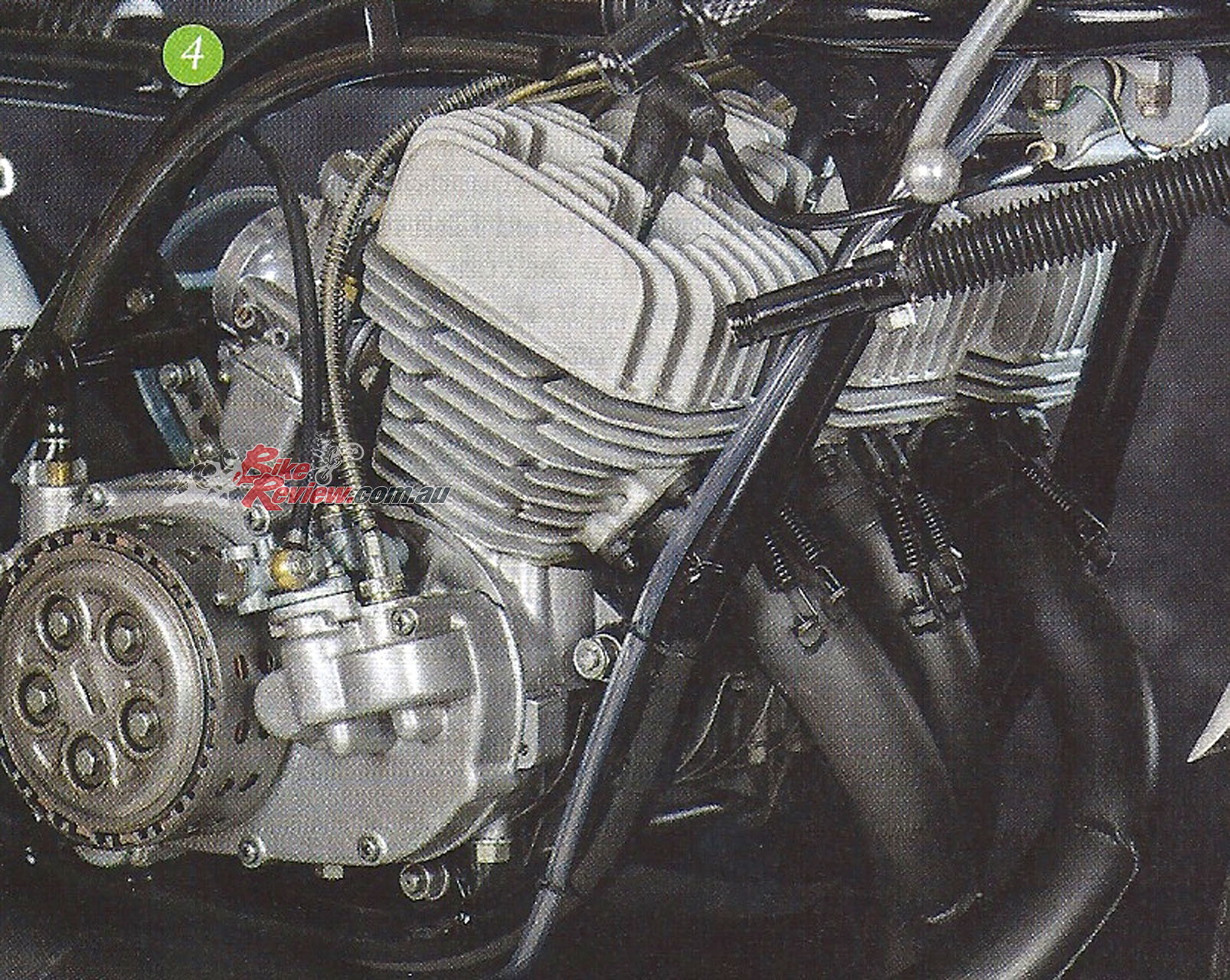

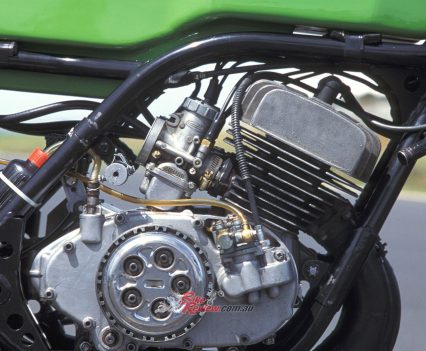

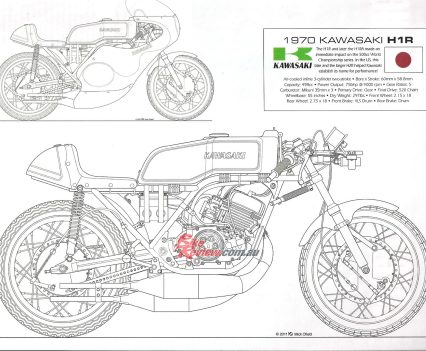

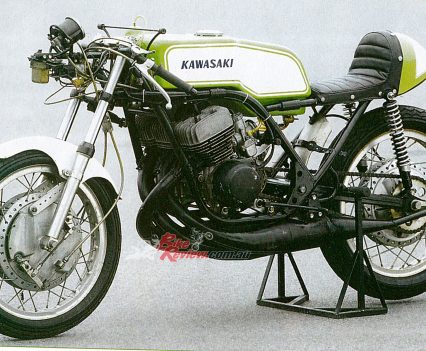

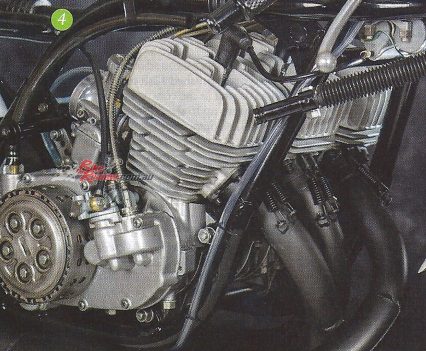

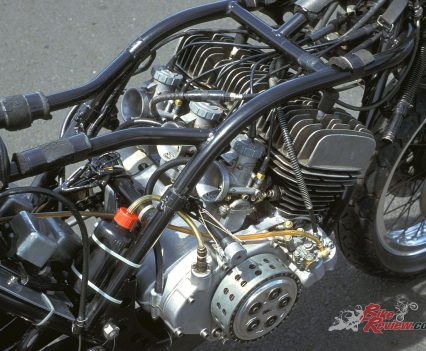

Closely based on the H1 Mach III roadster, the 40 air-cooled H1R road racers that Kawasaki built in total employed the same crankcase, cylinder and detachable cylinder head castings as the H1. The 498cc piston-port engine’s architecture featured three separately-cast air-cooled cylinders, each with a large single intake and exhaust port and five transfers, mounted transversely in line on the crankcase, and fed by a trio of specially-developed Mikuni VM35SC carbs, which most owners took out to 36mm.

Lubrication was provided via Kawasaki’s trademark injector system supplied from an oil tank in the seat, and mounted on the right end of the 120° crankshaft. This fed the main bearings, big ends and, via the oilways drilled in the special H1R rods, the needle roller small end bearings, although some owners mistrustful of it dispensed with this system in favour of around 5 per cent premix fuel. But once those educated on four-stroke singles had mastered the critical skills of setting the carb jetting on a two-stroke correctly, the H1R gained a reputation for reliability – only broken cylinder studs were a perennial problem.

Forged two-ring pistons 20 grams lighter than the Mach III equivalents, with offset wristpins to reduce slap at either end of the piston stroke, were fitted to the 60 x 58.8mm engine. The five-speed close-ratio gearbox was matched to a dry clutch mounted behind the oil injectors, while the Mach III’s electronic ignition was replaced by a battery and three coils for the racer, complete with alternator – apparently Kawasaki technicians thought the CDI was too complicated for racers to understand!

The Mach III’s electronic ignition was replaced by a battery and three coils for the racer, complete with alternator – apparently Kawasaki technicians thought the CDI was too complicated for racers to understand!

However, most owners like Molloy fitted a Kröber transistorised system, which saved lots of weight by letting them junk the battery, alternator etc., as well as preventing misfires caused by any slight movement in the crank bearings upsetting the points timing.

Delivering a claimed 75bhp@9,000rpm in stock form, over one-third more than a Manx Norton or Seeley G50 which actually weighed more dry than the 135kg Kawasaki, the H1R¹s big handicap was its very high fuel consumption, around 18L/100km. However, scare stories about 23L/100km thirst which arose when the bike made its debut at Daytona in March 1970, only came about through confusing Imperial and American gallons!

Even so, the fuel load needed to satisfy this thirst in the days when FIM rules stipulated GP races must be at least one hour in length, was a real penalty. This was true not only in terms of weight and lost time making pit stops to refuel (as all H1R riders who didn’t use premix had to do as a matter of course in GP races, even once the oil tank in the seat had been converted to a secondary fuel tank, and a new oil container mounted above the gearbox where the battery used to be) but also because a bike already featuring some compromises in its chassis design didn’t handle any better carrying 30L of fuel!

The width of the three-cylinder engine meant it had to be mounted very high in the duplex frame (essentially a lightweight copy of a Norton Featherbed chassis) in order to gain acceptable ground clearance. The crankshaft was located no less than three inches (75 mm) above the centreline drawn between the wheel axles.

Sticking 22 litres of premix in the standard fuel tank, then adding another 8.5 litres in the tail, must have made the Kawasaki a real handful in the early laps of a GP race – or after a fuel stop! Stopping the bike must also have posed a real problem, which the 280mm four leading-shoe drum front brake, proved ill-equipped to do. Most owners fitted a lighter, more effective 250mm Fontana 4LS brake during 1970, and in 1971 disc brakes (usually sourced from the Honda CB500/750 parts bin) were commonplace, as fitted by Molloy for his 1971 season racing his 500 Kawasaki in the USA. Molloy used Konis on the twin-shock rear suspension, retaining the 35mm Kawasaki forks which had their sliders machined from solid billet.

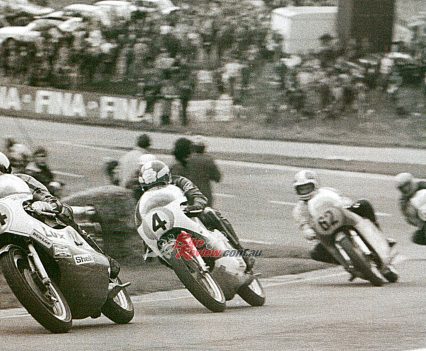

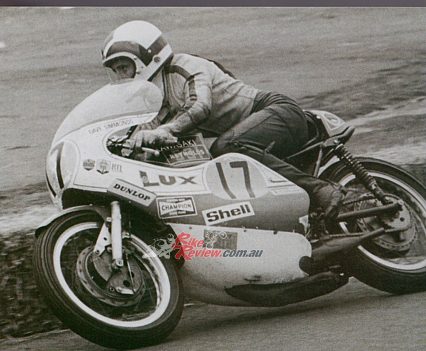

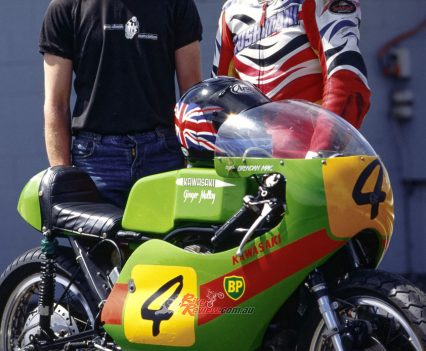

Molloy racing in Australian during the 1972 season, now with twin front discs rather than that horrid drum…

The H1R made a winning debut at Daytona in March 1970, when the first customers took delivery of their bikes and Texan Rusty Bradley won the 100-mile Junior race on the Boston Cycles machine. In the Daytona 200 – for which the H1R was eligible under the new F750 rules, thanks to its Mach III roadster ancestry – Ginger Molloy finished 7th on his new 500 against all the 750s, behind Dick Mann’s victorious Honda CR750. The Kiwi was best private owner and best non-American with a completely standard bike, which had been uncrated and assembled only days before, but which was still trapped at 159.83mph on the bankings.

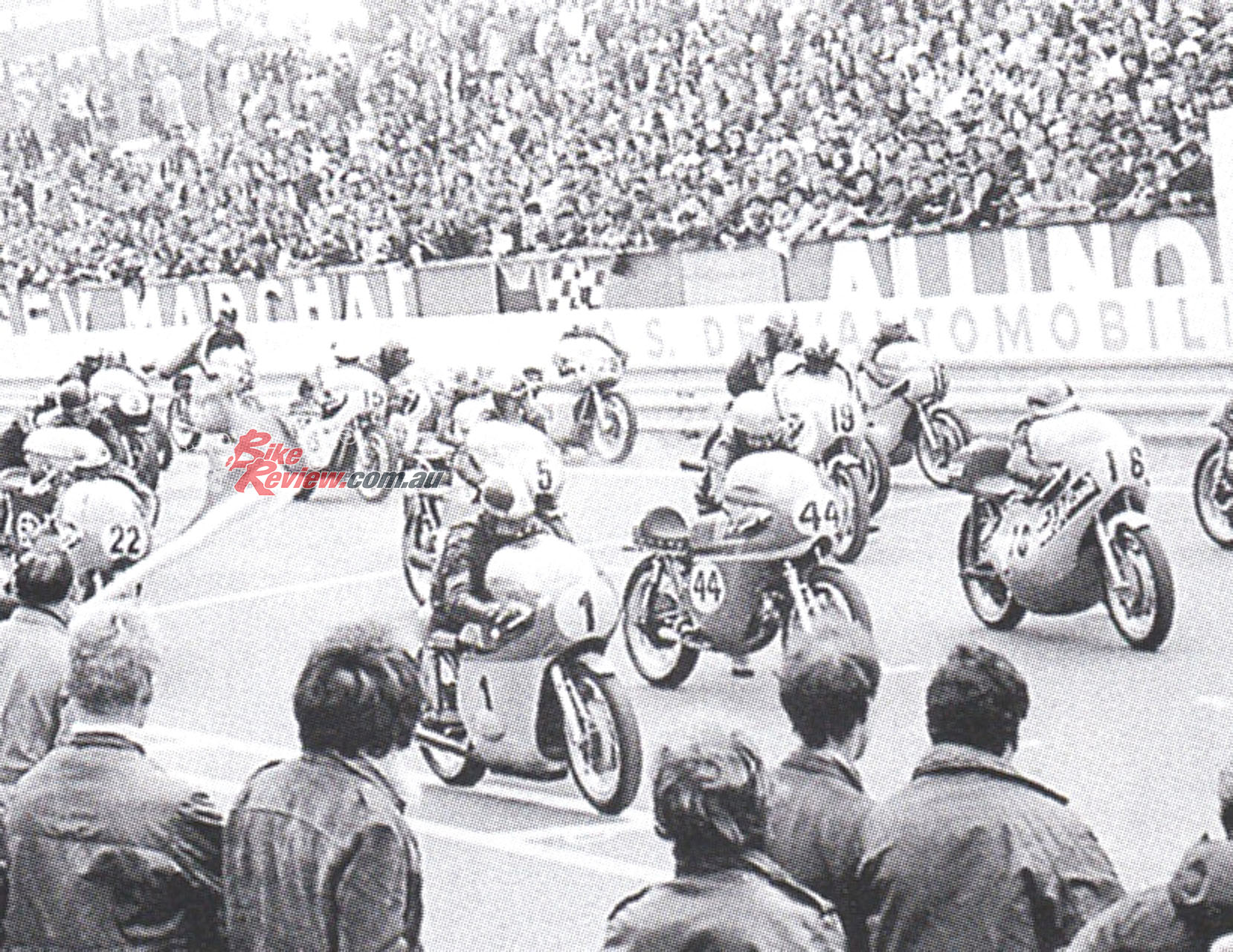

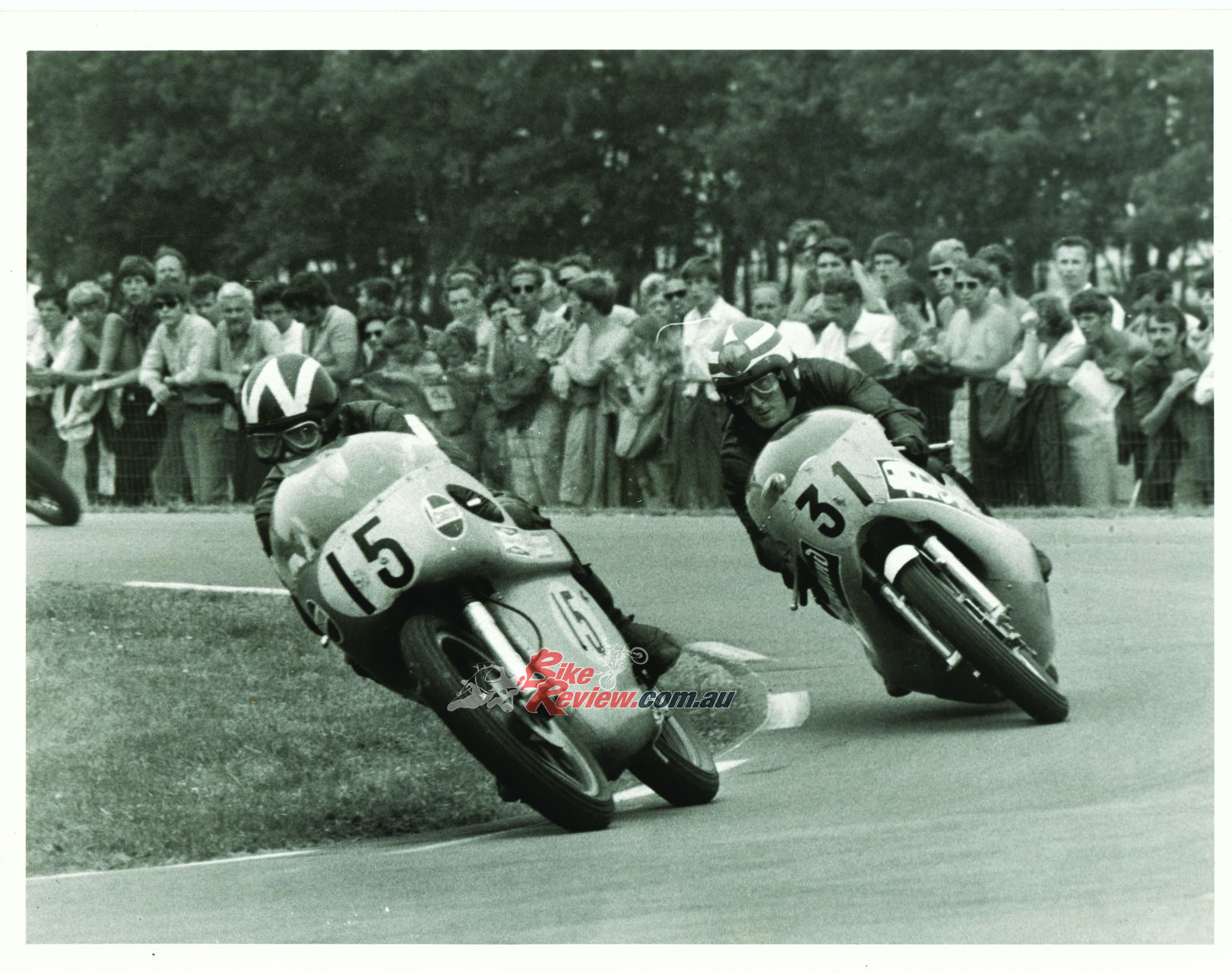

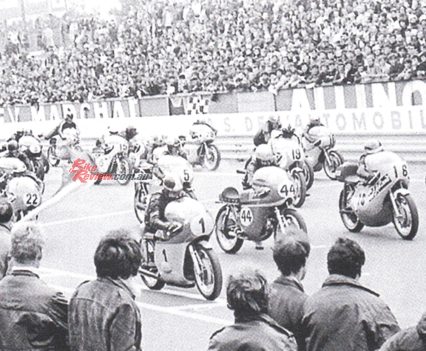

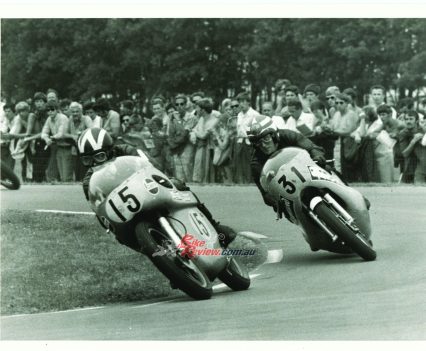

Once in Europe, Molloy’s H1R began to pay its way at the non-championship internationals which were vital to a privateer’s race budget, with third at Cervia in Italy, and fifth amid the snow and ice of Austria’s Salzburgring. Similar weather was in store for the first GP of the season at the Nűrburgring, in which Ginger played safe and rode his 360 Bultaco to fifth place, but in the French GP at Le Mans two weeks later, he gave Kawasaki its first-ever 500GP rostrum finish with a superb second place behind Agostini’s MV, after being last away at the push start.

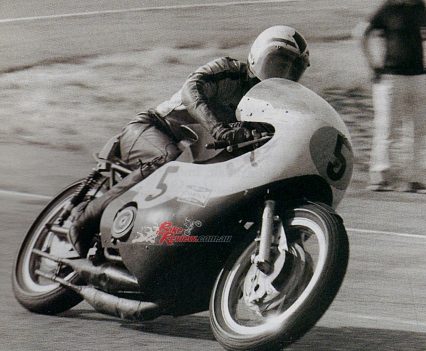

Ago looking back at Molloy on the H1R at the 1970 Ulster GP. Imagine Ulster on a 500cc two-stroke… mental!

It was a GP debut which served notice that the H1R was only fractionally slower than the MV on both acceleration and top speed, yet far from being a billion-lire factory team’s racer, could be bought for just $1,500 plus tax and shipping costs through your friendly local Kawasaki dealer.

$1500 went a long way back in the 70s. Imagine turning up to race a MotoGP season with a bike you bought off the showroom floor…

Two obligatory pit stops necessitated by the Kawa’s thirst, as well as a slight but annoying misfire, had let Ago off the hook at Le Mans, but for the next GP on the Opatija street circuit in Yugoslavia, Ginger converted the seat tank to fuel and mounted a small cylindrical oil tank in front of the rear mudguard. But the adverse effect on braking of this extra load was underlined when he rammed Pagani’s works Linto at a hairpin, then got blinded by fuel spraying into his open face helmet from the breather pipe, so seventh under the circumstances was a bonus.

Opting to miss the TT, he raced instead at the non-title Yugo race at Skopja-loka, and scored the Kawasaki’s first race victory, setting a new lap record in the process. Fitting a wider WM3 rear rim – the H1R was definitely under-tyred in stock form, with 3.00 and 3.25 front and rear tyres both on WM2 x 18 inch wheels – he headed for the Dutch TT at Assen hoping to give the MV a close run for victory, on a circuit where he had twice finished second in the Dutch GP, on the same day.

But it was not to be: the Kawasaki wouldn’t rev properly at Assen, pulling only 8,000rpm instead of its peak 8,800 revs (and 9,500rpm redline), and the misfire was still there. Ginger still finished fourth, but the next two GPs in Belgium and the DDR were a disaster, with retirements in both races: the crankshaft needed attention. Unable to obtain original parts, he fitted a reconditioned crank with home-made crankpins and German Dürkop cages, which lasted longer than the Japanese rollers in the six-bearing crank. Together with the Kröber ignition now fitted, this transformed the Kawasaki into a fast and reliable machine, which actually allowed him to lead the Finnish GP at Imatra at half-distance, before Agostini inevitably overtook him.

Second place there was followed by another in the Ulster GP, when again the Kiwi Kawa privateer led the works MV, only to have to stop for fuel, allowing Ago to win by just under two minutes. Sixth at Monza in the Italian GP was a disappointment – even if no less than seven Kawasakis finished in the first ten, behind the inevitable pair of MVs. This came thanks to a power loss caused by overheating from the alloy casing round the generator, which Ginger ventilated, as well as taking a file to the ports.

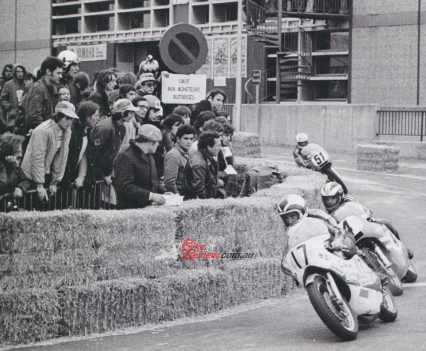

The 1970 Monza round was a disappointment for the H1R, battling with mechanical issues it still came home for an impressive sixth place.

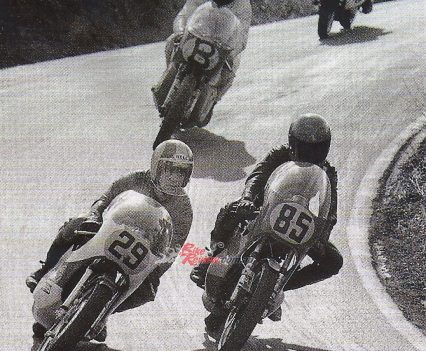

His handiwork paid off, with third place in the non-title race at Imola the next weekend, then victories in similar races in Austria and Yugoslavia. The H1R was paying for itself! To round off a highly successful debut season, Molloy rode the Kawasaki to another second place, his fourth of the World championship season on it, in the Spanish GP in Barcelona. This must have given him extra satisfaction because of his long connection with the Catalan capital as a semi-works Bultaco rider, as much as for the second place in the 500cc World Championship that it clinched for him, after scoring points in eight of the eleven rounds. It was the first time a two-stroke finished in the top three of the 500GP World title chase.

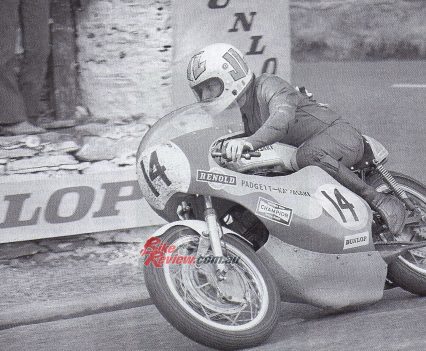

Molloy took the Kawasaki to America for the 1971 season, but Kawasaki’s ex-125cc World champion Dave Simmonds wound up fourth in the 500GP World series that year, after four rostrum finishes on his Reynolds-framed H1R. This included scoring the model’s only Grand Prix victory in the end-of-season Spanish GP at Barcelona, with Agostini non-starting as he’d already clinched the title. Simmonds had attempted to resolve the H1R’s uncertain handling on full tanks with a Ken Sprayson-built frame which distributed the weight better, and France’s Eric Offenstadt was another to attempt to do so on his self-built machine – the first-ever monocoque-framed 500GP racer.

The Offenstadt machine carried no less than 37 litres of fuel, ensuring Eric never needed to stop to refuel in a race, yet had a dry weight 8kg lighter than the stock Kawasaki. He finished sixth in the points table with three rostrums – but in general the three-cylinder Kawasaki was now yesterday’s papers, the lighter, less thirsty Suzuki 500 twins now having the upper hand as a privateer tool.

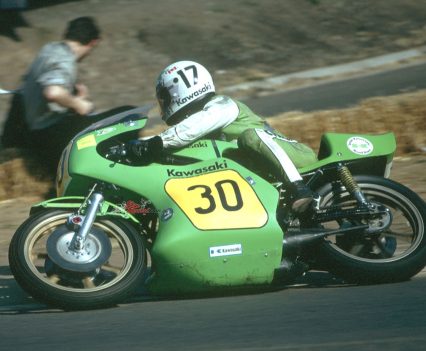

A water-cooled version of the 500cc Kawasaki appeared in 1975, the H1R-W. Only three were built and were raced by Mick Grant, Barry Ditchburn and Yvon DuHamel, with Grant’s 1975 Isle of Man Senior TT and North-West 200 victories their only real success. Delivering 88hp@9,500rpm they were raced in several GPs that year, proving a little underpowered and suffered from poor reliability.

The Grant and Ditchburn bikes were upgraded with a KR750-style front end for 1977, with the third bike used for spares. In 1980 Kawasaki would return to 500GP racing, this time with an official factory team headed by Kork Ballington racing a liquid-cooled monocoque-framed rotary-valve square-four. But that’s another story….

Ginger Molloy Kawasaki H1R History Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.

September 4, 2025

I realise this is an old article but a couple of things strike me: firstly the frame is described as basically a lightened featherbed copy but from the pictures above, it looks to my rather inexperienced eye, more like a BSA. Secondly, whilst Ginger missed the TT, there was a Kawasaki on the 1970 podium, behind Ago and PW, ridden by Bill Smith. Little seems to have been recorded about this but I wonder if this was an H1R? Thanks, Nick