The ELFe is one of the most obscure line-up of motorcycles to ever grace the racing world. Alan Cathcart gives us the racer test and comprehensive history of the machine. Photo credit: Kel Edge

ELF, a French oil giant, became one of the biggest names in endurance racing and motorcycle innovation of the ’80s. At the head of this strange collaboration was one of the most interesting motorcycles the endurance racing scene has ever seen, the ELFe…

ELF, a French oil giant, became one of the biggest names in endurance racing and motorcycle innovation of the ’80s.

40 years ago in the 1980s there was a proliferation of radical approaches to motorcycle design. Chassis development had been increasingly unable to cope with the fruits of the horsepower race among the Japanese manufacturers. Hence the controversial move to reduce the capacity limit of TT Formula 1 racing from 1000cc to 750cc for 1984, and the decision of the FIM, prompted by Japanese manufacturers, to explore reducing the 500GP limit to 400cc as a way of reducing power, and thus speeds. But several viewed this as stop-gap thinking: inevitably, a couple of years on those downsized 750s would be producing the same sort of power as one-litre bikes today.

Read our other Throwback Thursdays here…

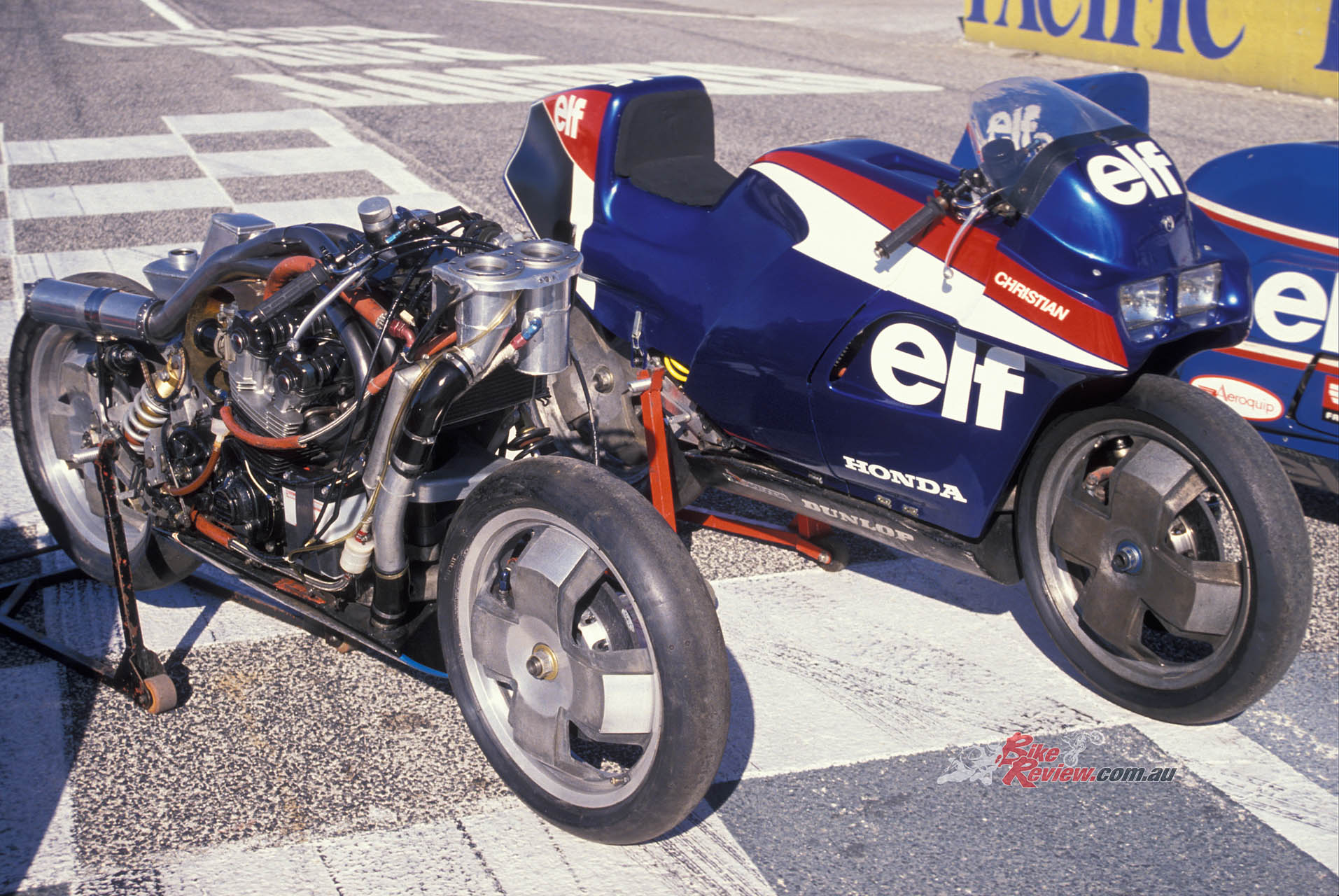

Time for a long overdue fresh look at basic motorcycle design. Followers of the Endurance racing scene knew that long, hard look had already been taken by French oil giant ELF. In 1982-83 the radical ELFe (for Experimental) Honda-powered racer had been one of the front runners in the long distance classics, albeit without ever winning one despite coming close in a couple of races.

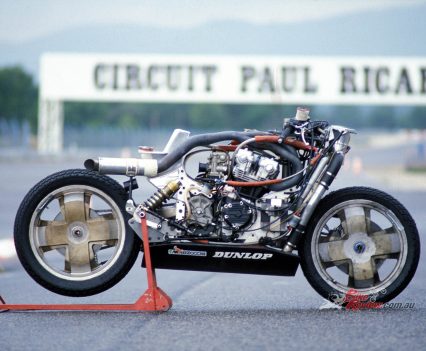

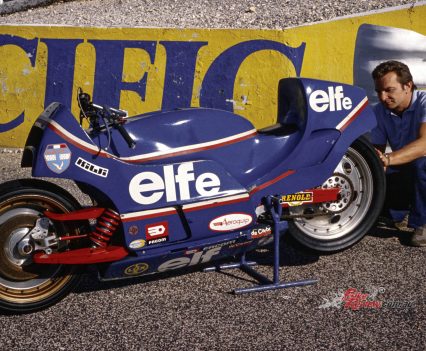

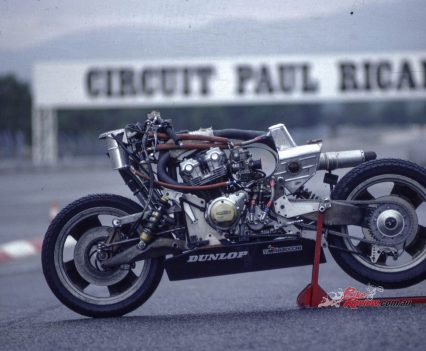

At the end of 1983 ElF’s Marketing and Competitions chief, François Guiter – the man responsible for conceiving and funding the succession of radically avantgarde ELFe racers – invited me to Paul Ricard to try out the complete range of four all-but identical ELFe bikes which the team had constructed and raced in 1982-83. With the 1984 advent of the 750cc TT F1 rules these 999cc devices were now ineligible for competition, and thus due for retirement to life in the ELF corporate museum. But not before I’d ridden them!

At the end of 1983 ElF’s Marketing and Competitions chief, François Guiter, invited Alan to Paul Ricard to try out the complete range of four all-but identical ELFe bikes.

The ELFe’s roots lay deep in the heart of automobile technology, even though its concept was mirrored in a classic case of parallel development by the British Difazio/Tomkinson endurance racer – later to be known to one and all as ‘Nessie’ – which first appeared in Laverda-engined form a year before the first ELF X two-stroke Formula 750 prototype was unveiled in 1978.

Read Cathcart’s test on the Swissauto ELF 500 here…

There’s no suggestion that one design copied the other – simply that two different people in two separate countries each decided at about the same time to work along the same lines to eradicate some of the more ingrained faults of motorcycle design.

The ELF’s creator was André de Cortanze, then 42, one of the original minds behind the Renault Formula 1 Turbo racing car, and before that designer of the first-ever turbocharged Endurance 4-wheeled racer, the Alpine A442. He still worked for Renault as a development engineer, but in an example of the sort of inter-company collaboration whose spirit helped explain France’s resurgence as a competitive force on two and four wheels in that period, was given leave to work on the ELF bike project by them.

In 1977 ElF’s François Guiter gave de Cortanze the money to produce such a bike, and the TZ750-engined ELF X which appeared in 1978 was the result.

A former successful Enduro rider till he’d broken his leg badly a few years earlier, de Cortanze’s first brush with the motorcycle Endurance world came when he helped design the oddly-shaped but effective bodywork for the Japauto Hondas in the mid-‘70s.

Read our feature on the Japauto Honda here…

But it was the ELF-sponsored Renault connection, rather than rival oil company Total’s Japauto, which led to the chance to design and build a racing motorcycle incorporating many of the new ideas for chassis design which he had. In 1977 ElF’s François Guiter gave de Cortanze the money to produce such a bike, and the TZ750-engined ELF X which appeared in 1978 was the result. Although it only raced once, Guiter was sufficiently impressed to offer de Cortanze a much bigger budget to build and develop an Endurance racer: Ecurie ELFe was born.

Although it only raced once, Guiter was sufficiently impressed to offer de Cortanze a much bigger budget to build and develop an Endurance racer: Ecurie ELF was born. Then came the rest of them… stunning.

“From the very beginning I tried to rid myself of every preconceived notion of what a motorcycle should look like,” de Cortanze told me when I visited his atelier [design studio] in Paris in 1983. “I concentrated instead on how it really ought to be. I had four principal aims: to lower the centre of gravity, incorporate ‘natural’ anti-dive and anti-squat suspension, reduce weight and eliminate the chassis completely. There were various secondary objectives too, like achieving a 50/50 weight distribution, reducing the frontal aspect and lowering the drag factor, improving the braking, be able to change the wheels quickly in Endurance racing, and so on. I would say that I’ve achieved everything I wanted to with the current machine – for me, it’s obsolete, and so I don’t really mind that the change in capacity limits will rule us out of racing with it next season. For me the next step is to increase the tyres’ contact patch with the ground in all modes, which in turn requires much work to be done on the suspension, and so a completely new bike is in order.”

In 1982-83 the radical ELFe (for Experimental) Honda-powered racer had been one of the front runners in the long distance classics. Seen here at the Bol d’Or, Walter Villa onboard.

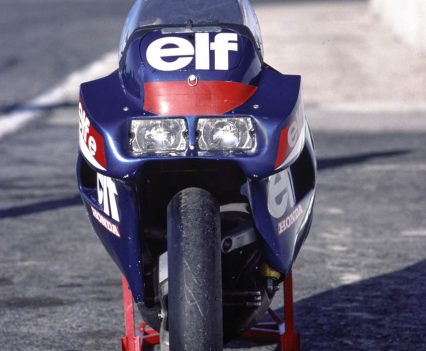

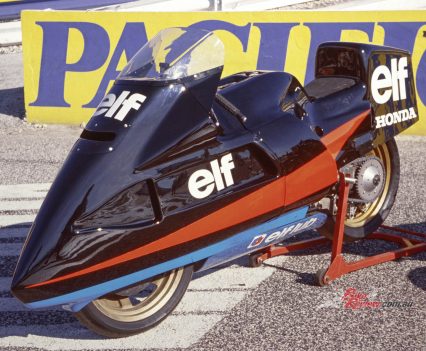

When the ELFe first appeared at the Bol d’0r in 1981, powered by 999cc RSC Honda engines which the Japanese factory had agreed to supply the team with after one of their testers rode the TZ750 version at Le Mans the year before, and was reportedly highly impressed by it, onlookers were dazzled by its design and execution.

When the new bike, ridden by development riders Christian Leliard and four-time World champion Walter Villa, led the first two laps of the race and stayed in the leading group till the rear axle broke after 8 hours, a breakthrough in motorcycle engineering seemed on the cards. While the ELFe’s subsequent results didn’t live up to either the hopes of the team or the expectations of outsiders, the responsibility for this must equally fairly be laid at the door of the then year-old Honda engines, rather than at de Cortanze’s design.

Time and again the bikes were sidelined with one engine malady or another while well placed. However, although both entries retired from the 1983 Bol d’Or, Ecurie ELF’s endurance effort signed out with a flourish a week later when 250GP stars Didier de Radiguès/Herve Guilleux finished third in the final round of the World Endurance Championship at Mugello, behind two works Kawasakis but ahead of the title-winning Suzuki team, while Villa/Leliard came ninth. The two bikes, plus one lightweight ‘qualifier’ and an 1123cc version for use in the prototype class in non-Championship events, were waiting for me to try at Paul Ricard at the end of November.

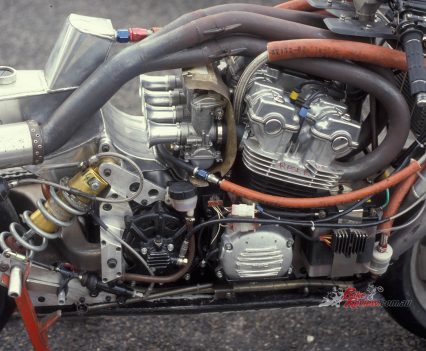

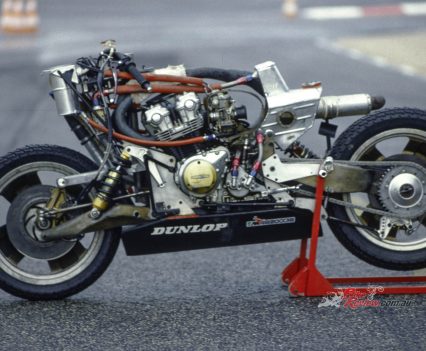

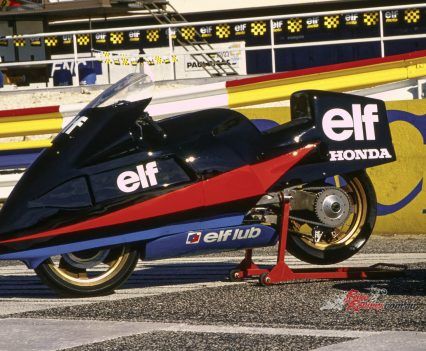

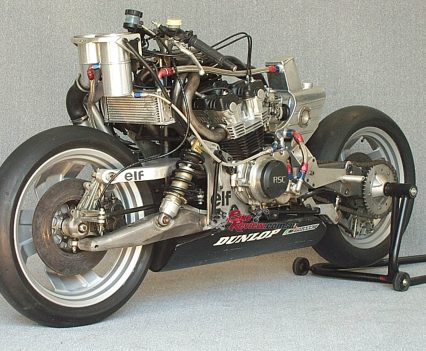

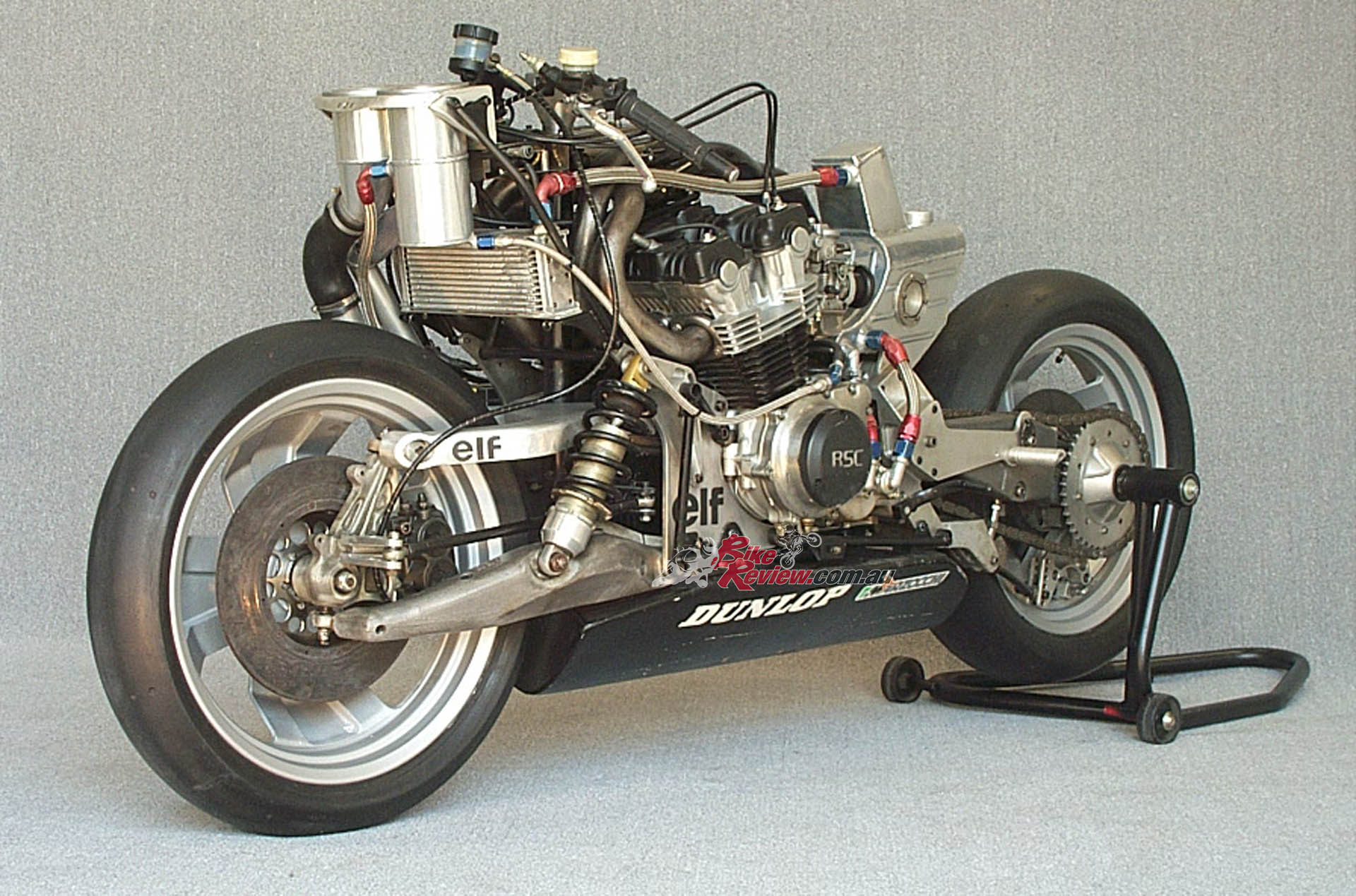

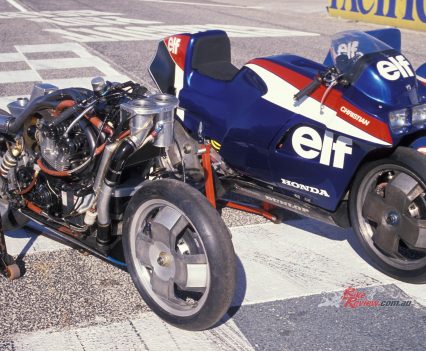

The ELF’s design was centered around de Cortanze’s contention that telescopic forks were an engineering abomination, ready to flex or twist under heavy braking or cornering, especially with the modern generation of slick tyres. If you do away with tele forks, continued the de Cortanze philosophy, then there’s no need for a chassis, which is simply a means of supporting a steering head from which to suspend the fork. So the Honda in-line four-cylinder engine acted as a fully-stressed member, F1 car-style, to which the single-sided front and rear suspension and ancillary components were attached via aluminium plates.

“The ELF’s design was centered around de Cortanze’s contention that telescopic forks were an engineering abomination, ready to flex or twist under heavy braking or cornering.”

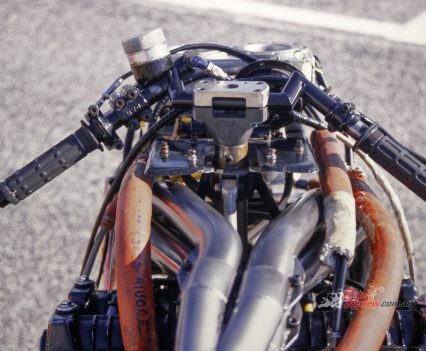

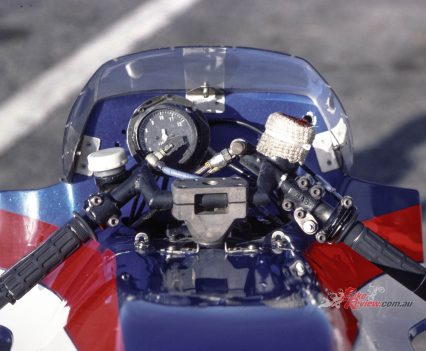

Up front, hub-centre steering was employed with twin parallel swingarms, with suspension via a fully-adjustable Marzocchi monoshock with remote gas reservoir. The handlebar was bolted to a block at the top of the steering column, which rotated in two ball races top and bottom, and transmitted the rider’s intentions via a pair of steering arms connected by an adjustable tie rod. Two larger spherical rod-end bearings, aka rose-joints, acted as the pivots for the hub-carrier steering arm, which thus neatly did away with the need for a pivot within the hub, and had the important side-benefit of enabling quickly-detachable wheels to be fitted.

The wheels were specially-made ELIA cast magnesium items weighing a scant 3.2kg each, with single-bolt attachment front and rear that enabled a full wheel change to be carried out in 18 seconds thanks to the single-sided rear swingarm which allowed the wheel to be removed without disturbing the sprocket or chain. The front wheel only could be changed in the time it took to add 23 litres of fuel and change riders – an astounding 11 secs. “A little slow, but we lose two seconds having to open the flap in the nose which covers the filler!” explained head mechanic Alain Chaligne, de Cortanze’s right-hand man throughout the ELF project. So 11 seconds to change the front wheel, add five gallons of four star and swap riders is slow??

The wheels were specially-made ELIA cast magnesium items weighing a scant 3.2kg each, with single-bolt attachment front and rear that enabled a full wheel change to be carried out in 18sec.

To assist in lowering the centre of gravity, de Cortanze had placed the fuel tank beneath the engine, in contrast to the exhausts which now ran up and over the top of the motor – a format which was imitated by Honda on its first-generation NSR500 in 1984. Fortunately the wind-tunnel tested all-enveloping aerodynamic bodywork was thick enough to prevent the rider becoming overheated. “Empty exhausts weigh less than a full fuel tank,” said de Cortanze!

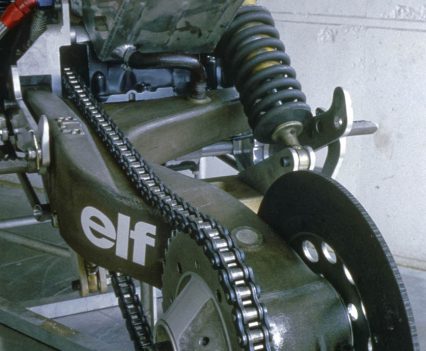

The team only once ever had to change a chain even in the course of a 24-hour race, which was a great advert for the ELF’s rear suspension design, which ensured constant chain tension by placing the pivot of the cast magnesium swingarm coaxially with the gearbox sprocket. Another special Marzocchi shock sat inboard of the rider’s right foot, working off the swingarm via a set of aluminium rocker arms, the whole attached to the rear of the gearbox via more dural plates.

Because of the QD wheels only a single brake disc could be fitted, but here again the team broke new ground, having been the first in motorcycle racing to use carbon discs which weighed next to nothing, and were made by the same French SEP concern that manufactured the brakes for Concorde aircraft. A four-piston Lockheed F2 car caliper was used up front, with a Brembo Serie Oro two-piston rear.

“A problem associated with carbon discs is that they hardly work at all when cold, a fact I almost discovered the hard way when I gripped the brake at the end of the Mistrale straight on my first lap.” said Alan.

A problem associated with carbon discs is that they hardly work at all when cold, a fact I almost discovered the hard way when I gripped the brake at the end of the Mistrale straight on my first lap on the bike – and nothing happened! Back in the pits Walter Villa offered sympathy: “The first time I rode it the same thing happened to me! What you must do is ride along for the first 200 metres holding the brakes on – that warms them up!”

Brake disc wear in 24-hour races was also a problem, as was wet running when the discs obviously stay cool, but overall de Cortanze was happy he persevered with them: “We and SEP have both learnt a lot, and while the reduction in unsprung weight is useful, the main point of using them is that they offer a reduction in gyroscopic effect, which improves the steering,” he said. But furthermore, thanks to these and other weight-saving touches the ELF scaled in at a competitive 173kg ready to race, with oil but no fuel in 24-hour form – i.e. with lights: the ‘qualifier’ Sprint bike was a mere 168kg.

This was not of itself remarkable – the 1982 Endurance title-winning KZ1000Performance Kawasakis weighed the same – but where the ELFe did have an edge was on top speed and fuel consumption, thanks to the distinctive tricouleur-painted streamlining which de Cortanze developed in the course of several laborious hours spent in the Renault wind tunnel. Best-ever trap time for the bike on the Mistrale was 287km/h in 1000cc TT1 form (293km/h for the 1123cc bike, which I sadly didn’t get to ride as it had a camera fitted for movie-making), considerably faster than the competition.

“Best-ever trap time for the bike on the Mistrale was 287km/h in 1000cc TT1 form, considerably faster than the competition…”

Its very low drag factor also resulted in better fuel consumption, an important factor in Endurance racing, and at the same time de Cortanze was able to design the bodywork so as to achieve his targeted 50/50 weight distribution with the rider in place.

The funny little flyscreen didn’t seem very aerodynamic, though: zapping along the Mistrale it felt more like riding a ten-times faster version of an unfaired Manx Norton than a modern racebike, with no bubble to tuck your head under, “Actually, it’s only there for cosmetic purposes,” confided Walter Villa. “Provided you mould yourself to the bike, it makes absolutely no difference to the top speed. The coefficient of penetration is so good that if you tuck in behind another bike to slipstrearn it, you don’t go any faster as you might expect to do.”

Coming up behind a slower rider on one of the other bikes I tried to put this to the test, but discovered something else: the ELF was so slippery that it left a very small pocket of air behind it compared to a conventional bike, so it was difficult for riders of slower machines to get a tow off the ELF themselves.

Alan actually got two chances to ride the ELFe. Seen here in 1988 after the termination of the project, the only difference was the paint…

OK, so now you know what this revolutionary motorcycle is composed of: but now the big question – what’s it like to ride? In analysing my reactions I could do no better than quote Mr. Villa again: “First time you ride it, you think – hmm, not bad, but not quite what I expected! Then the second time – well now, this is really something. And then the third time – you fall hopelessly in love! Any other bike seems inferior, because it won’t do what the ELFe does.” Christian Leliard agreed: “In the three years I’ve been riding this bike, I’ve yet to discover its cornering limits. Provided you’re prepared to accept that two-wheel drifts aren’t just necessary but even desirable, there seems no limit to the speed you can enter a corner at, and still get round.”

“First time you ride it, you think – not bad, not quite what I expected! Then the second time – well now, this is really something. And then the third time – you fall hopelessly in love!” Said Villa.

Well, I can’t truthfully say I became a two-wheel drifter, but in the course of the two days I spent riding the ELFe I gradually wound myself up to riding it about as hard as I’d by then – nine years into my racing career – ridden any racebike, despite a fearsome Mistrale wind that threatened to blow the front wheel away at a couple of points on the track. The result was literally amazing: there seemed to be no limit to the bike’s capabilities, only to my own trust in them – and in mine too. In other words, the only barrier to going ever faster with the ELF into and around corners was a psychological one: what seemed to be on the limit by the standards of other machines was in fact perfectly well within those of the ELFe.

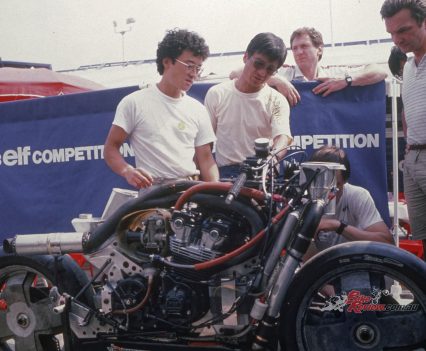

The ELFe with Christian Leliard and Japanese journalists. Ready to take the wild machine for a test.

How so? Well, take braking, for example. On a conventional racebike the ideal is to do all your heavy braking in a straight line while relatively upright, then flip it over and gradually apply the throttle to suit your cornering mode, and speed. Not so with the ELFe. Over the two days I found I could leave my braking seemingly suicidally later and later, then squeeze the front brake lever for all it was worth, as well as stamp hard on the back stopper, which normally I hardly used at all. The front end dipped ever so slightly, just enough to retain some feel to the suspension, and the bike stopped dead level and flat – no dive from the front end.

“Over the two days I found I could leave my braking seemingly suicidally later and later, then squeeze the front brake lever for all it was worth.”

That wasn’t so remarkable back then, except that it was achieved solely through suspension design, rather than an artificial anti-dive system of hydraulic valving or mechanical rods then used by most manufacturers’ race teams. But what was truly innovative back then was that you could bank the ELFe over as hard as you could while still braking hard, rushing deep into the turn way beyond where you’d have eased off the front brakes on another bike.

Welcome to the world of trail braking into a turn – something that’s taken for granted nowadays on tele-forked bikes with properly dialed in upside-down forks, but which back then would have been an invitation for the front suspension to freeze, resulting in a locked front wheel, and a trip to the kitty litter. That in turn meant you could brake yards later than the opposition: Leliard for example was braking at the 90-metre mark in practice for the Bol that year at the end of the Mistrale Straight – that’s from a terminal speed of over 280km/h!

“The ELFe’s riding position was slightly unusual because the bars were close together to achieve a wind-cheating posture and you were leaning downwards a bit, too.”

To be honest I found out how good the ELF’s brakes were quite accidentally: one lap in my second session a sudden enormous gust of wind caught me completely unprepared, and blew me past my normal barking point. Heavens, I’m the only Rosbif (French slang for a Brit!) yet to ride this bike, and here I am about to drop it in front of all the Froggies – maybe if I just sqeeeeeeze tight and pray, I can still get round. Five laps later I was braking ten yards further on still. Incredible.

The ELFe’s riding position was slightly unusual because the bars were close together to achieve a wind-cheating posture and you were leaning downwards a bit, too. However, it was perfectly comfortable for me and for its regular riders on the long haul, said Walter Villa, though low-speed manoeuvrability was poor, because it was impossible to exert much leverage on the bars, being so narrowly spaced. In fact, though, you’re not supposed to – and again, I found out the hard way. Coming out of the last turn before the Pits ending lap 1 of my first totally dry session, I cracked the throttle open hard, drifting up onto the kerb as I and most other riders did at that particular spot at Ricard. As the 125 bhp of the Honda engine chimed in all at once I was rewarded with a gigantic shake of the front end – if the tank was in the ‘proper’ place you’d have called it a tank-slapper!

“Low-speed manoeuvrability was poor, because it was impossible to exert much leverage on the bars, being so narrowly spaced.” said Cathcart.

Having sorted things out, I decided that maybe it was because I was riding the kerb, so in subsequent laps I took a tighter line and everything was OK. Back in the pits Leliard and de Cortanze came straight up to me: “I saw that!” said André. “Do you know why it happened?” You guessed it – nothing to do with the kerb. “You were trying to fight the front end – but the bike can react far quicker than the human mind. Next lap you were being much more careful, because you didn’t know why it had happened, but really you were being much more delicate, and that’s the way to ride the bike.” Didier de Radiguès agreed: “You mustn’t grip the bars as tightly as with a normal bike – it’s much more delicate to ride than people think. Each command seems to be carried out just as you think it, rather than as a conscious action. You must just sit there and pretend you’re driving a car with power steering – doucement!”

“Each command seems to be carried out just as you think it, rather than as a conscious action. You must just sit there and pretend you’re driving a car with power steering – doucement!” Said André de Cortanze about the ELFe

Compared to a conventional bike, the ELFe’s steering had a slightly remote feeling to it: you got the feeling that somewhere down there the wheel was turning in the direction you’d chosen, but you obviously didn’t get the same direct sense as with clipons bolted to the front forks. It did take a while to get used to, but after that you began to appreciate why skilled riders from such completely different backgrounds as Villa, Leliard and de Radiguès all raved about the ELFe.

By the standards of the day it was so positive and neutral to steer: it went where you pointed it with precision and immediacy, and that somewhere was much deeper into a turn than you could ever have dreamt of being able to go on two wheels while still braking hard. Part of the reason for this were the Dunlop tyres, especially developed in collaboration with de Cortanze for the ELFe by the British company – Michelin weren’t interested, strangely!

“The front in particular was unusual because it was much wider than usually fitted to other bikes, to be able to accept the extra cornering and braking forces.”

The front in particular was unusual because it was much wider than usually fitted to other bikes, to be able to accept the extra cornering and braking forces. The other main reason for the standout steering was de Cortanze’s unconventional steering geometry. On a bike with a 1435mm wheelbase, his steering head angle was a most unusual 29°, and the trail even more remarkable: “I always tell people that it’s a secret, but I will tell you that it’s much, much less than other bikes. In fact, it’s very, very close to zero!” And wheel travel was a rangy 140mm front and rear!

Streets faster than the opposition in a straight line thanks to careful attention to aerodynamics, the ELFe’s bodywork had also been designed to assist it in going round corners. The little handlebar fairings used to be adjustable for downforce till de Cortanze found the ideal position in the wind tunnel to impose maximum downforce on the front wheel, and moulded them into the two-piece streamlining. The rider was also supposed to help by sticking his knee out – seriously! “I used to ride in the classical style – knees in, bum on the seat,” Walter Villa told me. “Then I came to ride the ELF. André found in the wind tunnel that if you sit off the bike and stick your knee out, it not only has a positive effect on weight distribution, but also means the knee acts as a wind flap – it helps you spin the bike round the corner! Now I do it all the time!”

“Streets faster than the opposition in a straight line thanks to careful attention to aerodynamics, the ELFe’s bodywork had also been designed to assist it in going round corners.”

After my two days riding this avantgarde motorcycle in all kinds of conditions, wet and dry, still and windy, it was hard to escape the conclusion that this was indeed the way ahead for motorcycle design. All the riders were unanimous in believing this.

Leliard: “Dunlop’s participation will pay off for them tenfold, because in five years’ time all racing bikes will be like this. They have to be: the engines are now producing far more power than the present relatively primitive frames can handle, so the only possible way ahead is to concentrate on developing completely new concepts in motorcycle chassis design. We already have such a bike in the ELFe.” But Walter Villa went further: “It’ll be more than that. In 15 years from now all high-performance street motorcycles will have the same configuration as the ELF – it’s as day follows night. This is the way of the future – the ELF really is tomorrow’s motorcycle today.” Time would tell that wasn’t to be the case….

ELF MOTORCYCLE HISTORY: Doing It By Numbers

Under the direction of its Marketing boss François Guiter, for a decade back in the 1980s French oil giant ELF pushed back the frontiers of two-wheeled chassis design, using engines supplied by Honda to power a series of radical racebikes. Here’s a walk down ELF’s memory lane:

1978: ELF commissions French car designer André de Cortanze, an enthusiastic biker, to build a radical hub-centre racer powered by a Yamaha TZ750 two-stroke motor, known as the ELF X. It’s only raced once, but the enthusiastic public response dictates a follow-up.

1981-83: ELF links with Honda to produce the ELFe endurance racer, also designed by de Cortanze but this time around a Honda RSC1000 four-stroke engine. It’s raced by top riders like Dave Aldana, Didier de Radiguès, Walter Villa and Christian Leliard to a series of impressive results. Among the ground-breaking features of this hub-centre design are the first use of carbon brakes in motorcycle racing, and the single-sided rear swingarm design later christened the Pro-Arm, and used on the RC30 and its many successors under a licence purchased from ELF which had patented the design.

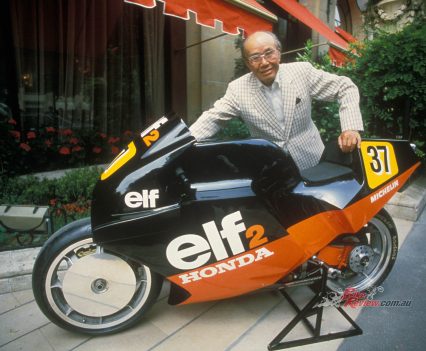

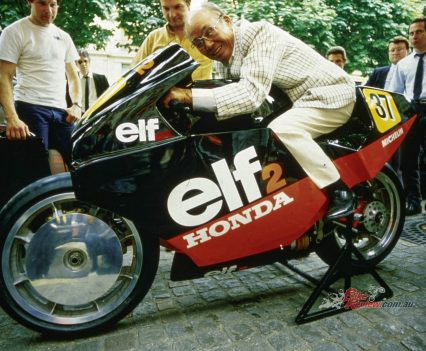

1984: ELF switches to 500cc GP racing with another hub-centre de Cortanze design, the ELF2, powered by Honda’s NS500 two-stroke triple. Soichiro Honda is sitting on the bike!

1984: ELF switches to 500cc GP racing with another hub-centre de Cortanze design, the ELF2, powered by Honda’s NS500 two-stroke triple and equipped with a unique push-pull steering design. But this is hard to become accustomed to, and the bike is not a success.

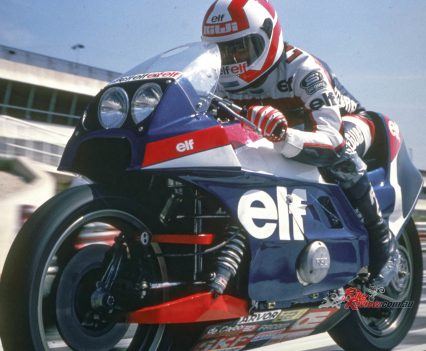

1985: De Cortanze produces the ELF2A, with which Leliard makes ELF’s 500cc GP debut, using an ever greater number of car-derived design features. Not a success, either: André returns to the car world, later to become the chief engineer of the Ligier Formula 1 team,

1986: ELF gets pragmatic, without sacrificing original thought, and hires Serge Rosset to run their GP team, with de Cortanze’s former right-hand man Daniel Trema designing the ELF3.

1986: ELF gets pragmatic, without sacrificing original thought, and hires Serge Rosset to run their GP team, with de Cortanze’s former right-hand man Daniel Trema designing the ELF3, equipped with a special front end design called the VGC system. Ron Haslam takes it to 9th place in the 500cc World Championship, still powered by Honda’s now outdated three-cylinder engine. The politically adept Trema later become le grand fromage of ELF sponsorship, in charge of the company’s entire Motorsports activity.

1988 and the ELF 5 saw the retirement of ELF from direct involvement in racing at the end of the season…..

1987: Honda agrees to supply ELF with its NSR500 four-cylinder engine, but this doesn’t turn up until after the start of the season, so the Trema-designed ELF4, broadly based on the ELF3, arrives late and is never properly developed.

1988: The NSR500-engined ELF5 takes Haslam to 11th in the World Championship, and proves the fundamental worth of the Trema/Rosset design module. ELF retires from direct involvement in racing at the end of the season…..

1982 ELFe Endurance Racer Specifiations

ENGINE: Air-cooled DOHC transverse in-line dry sump four-cylinder four-stroke, with four valves per cylinder and central chain camshaft drive, 999cc, 71.6mm x 62mm bore & stroke, 10.5:1 compression ratio, Kokkusan-Denki CDI, 4 x 33mm Keihin CR smoothbore, 5-speed close ratio gearbox with 15-plate all-metal dry clutch

CHASSIS: Engine used as fully-stressed structural member, with front and rear suspension attached via duraluminium plates, Centre-hub steering with remote pivots and twin suspension arms, with single fully-adjustable Marzocchi gas shock (f) Single-sided swingarm with fully adjustable Marzocchi gas shock (r) 1 x 300mm SEP carbon disc with AP-Lockheed four-piston caliper (f) 1 x 260mm SEP carbon disc with Brembo Serie Oro two-piston caliper. (R) 4.50-18 Dunlop slick on 3.50in ELIA cast magnesium wheel (F) 13.75/6.50-18 Dunlop KR133 on 5.50in ELIA cast magnesium wheel. 1435mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 128hp@8,000rpm (at rear wheel), 287km/h (Paul Ricard – Bol d’Or 1983), 50/50 with 75kg rider, 173 kg with oil/no fuel, including twin headlamps, rear light and alternator

Owner: Société ELF, Paris, France

ELFe Endurance Racer Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.