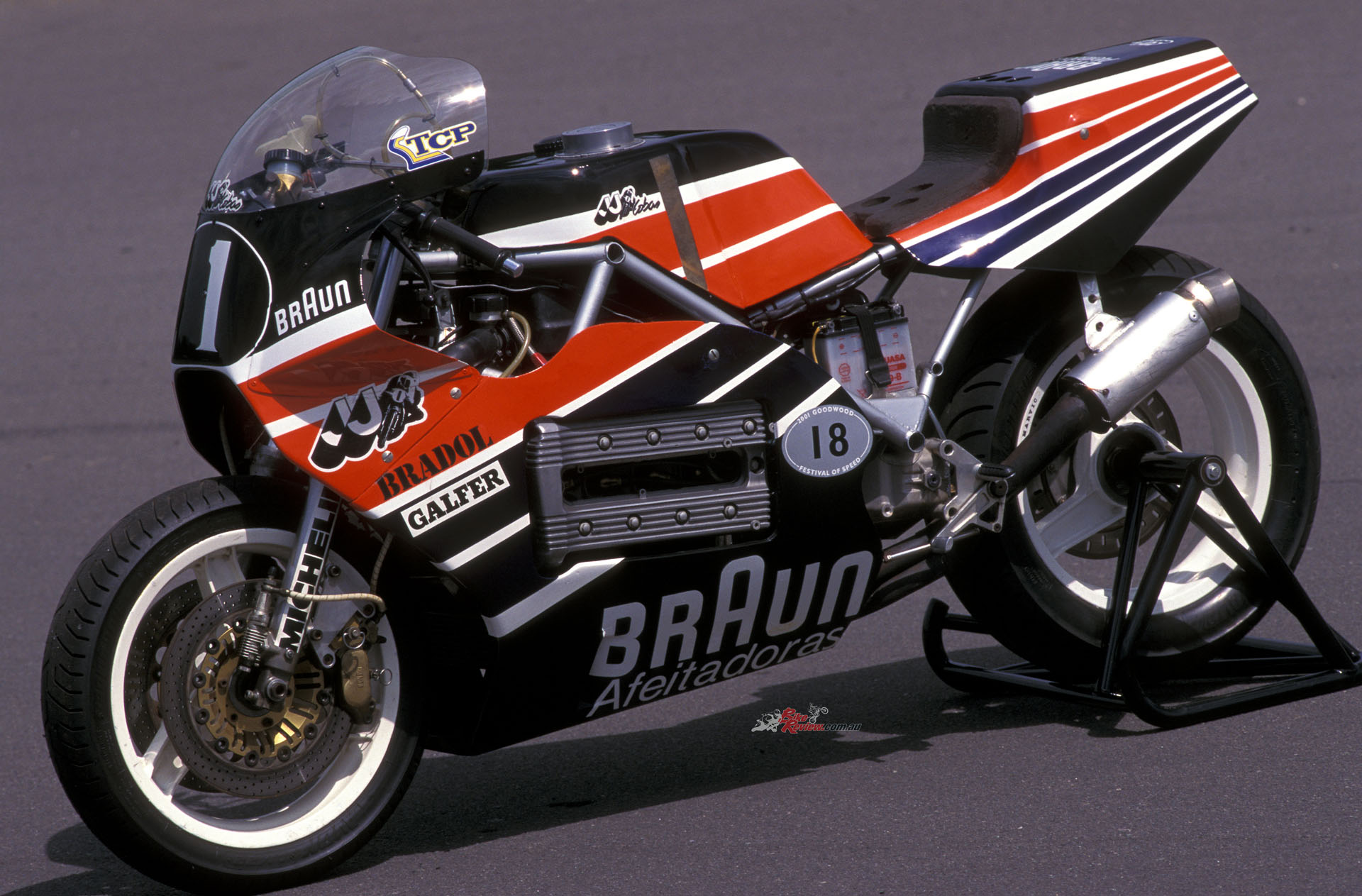

BMW have just become WorldSBK Champions! Amazingly, 40-years ago, a little known BMW Superbike defeated Yoshimura Suzuki, Bimota-Kawasaki, RSC Honda and Ducati to win the Spanish Superbike Championship... Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura

So you thought the WorldSBK title winning BMW M 1000 RR that Toprak Razgatlioglu just won on, 15 years after the debut of the S 1000 RR, was the German company’s first four-cylinder fuel-injected Superbike to win a major championship title, did you? Think again!

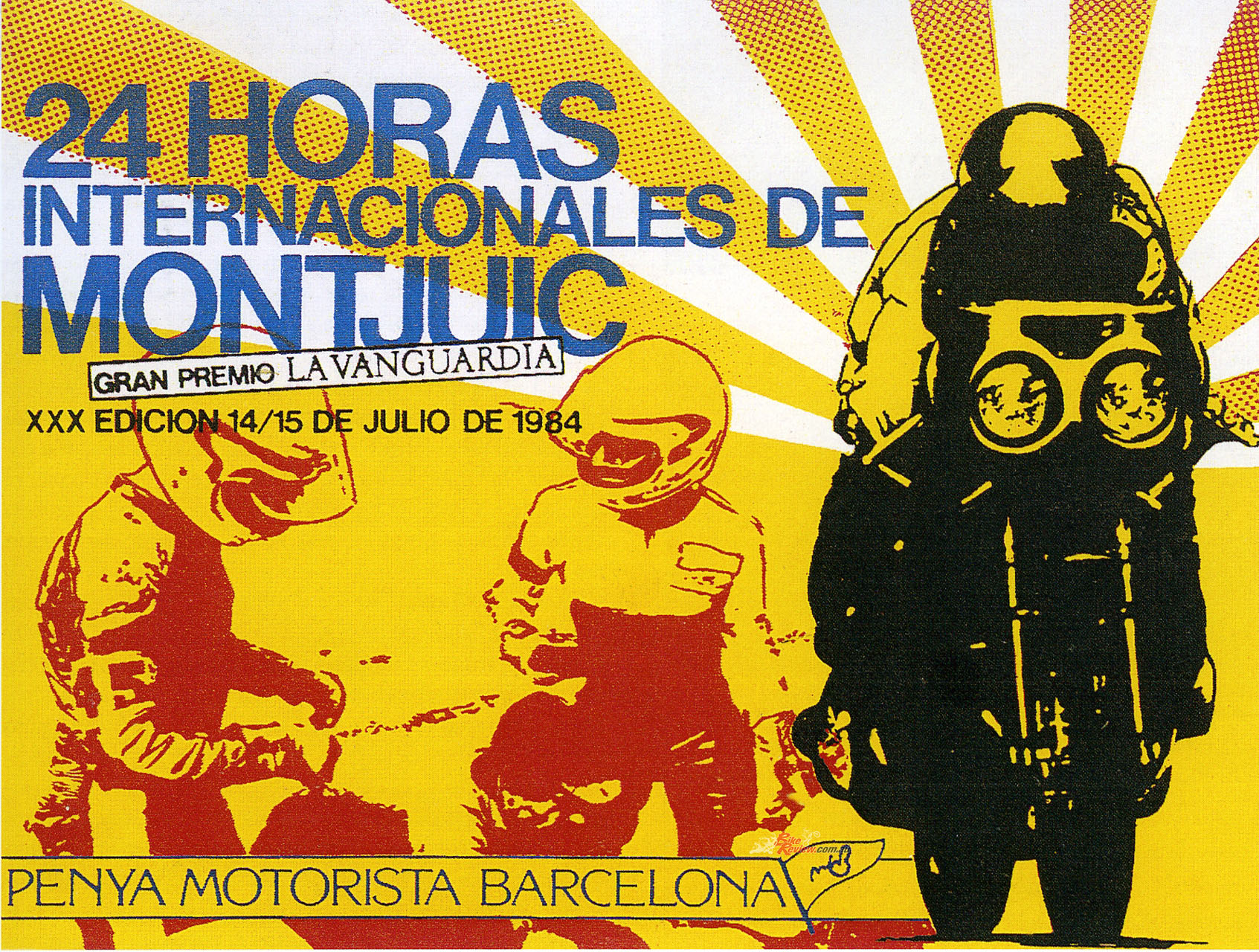

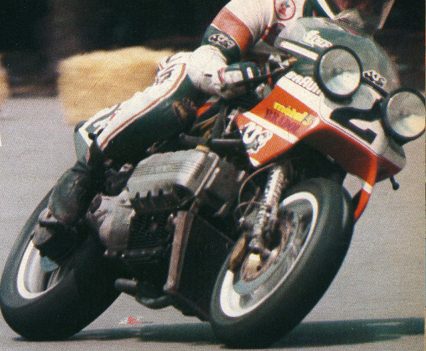

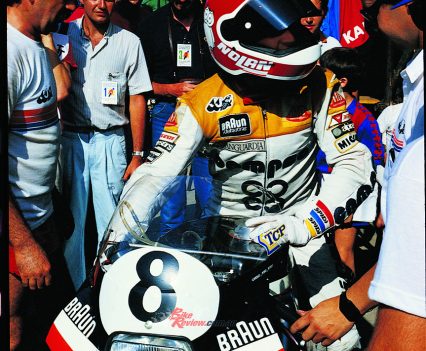

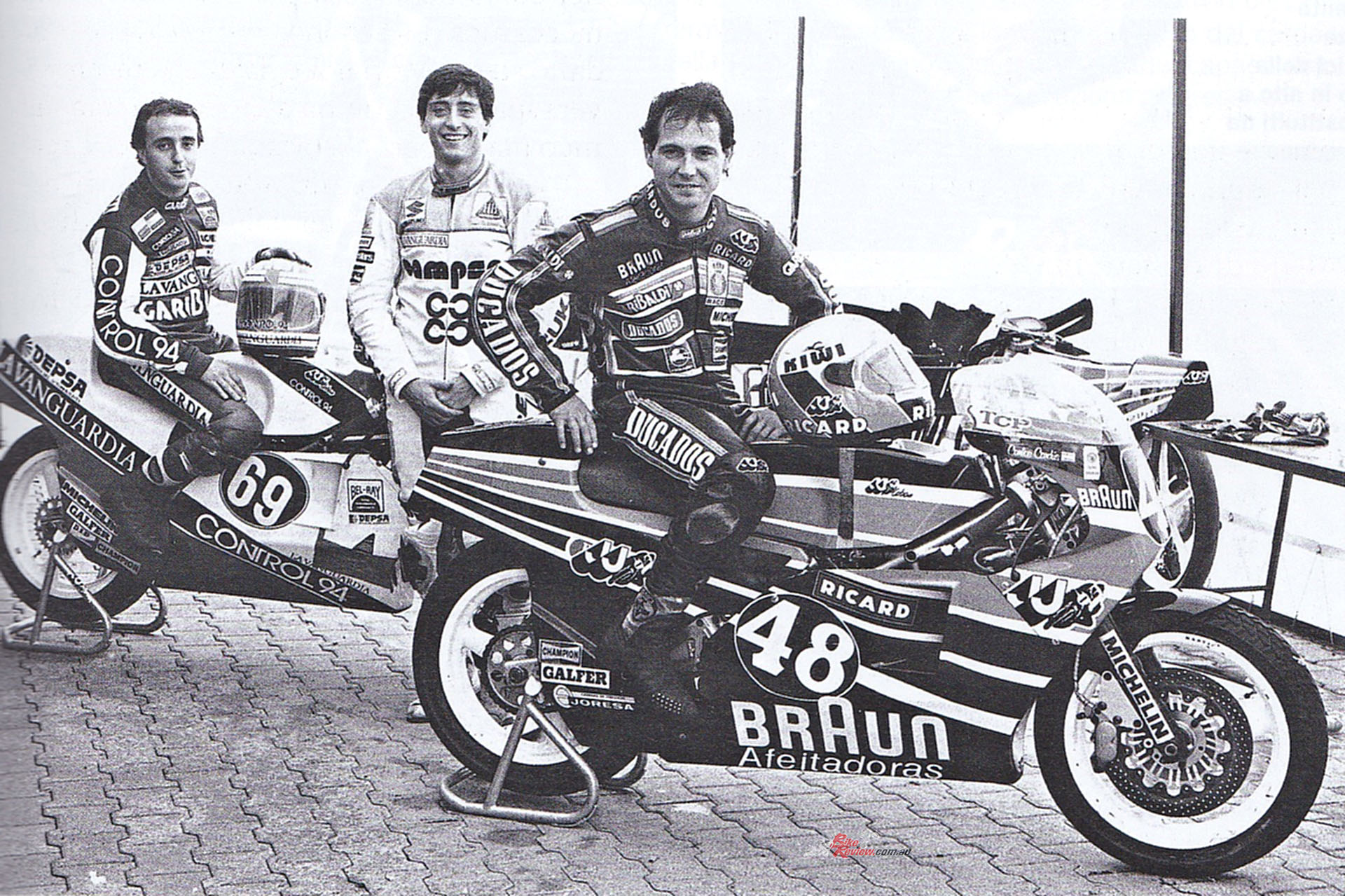

Because exactly 40 years ago, back in 1984, just such a bike defeated the Yoshimura Suzukis and Bimota-Kawasakis, not to mention the RSC-kitted Honda CB1000s and factory-supplied Ducati 950F1, to win the Spanish Superbike Championship in the hands of future Honda 250GP works rider, Carlos Cardús. And although its two highest-profile appearances on the international stage both ended in failure, when it attempted to defeat the dominant Ducatis to win the gruelling Montjuic 24 Horas endurance marathon, the 1000cc JJ-Cobas BMW four was literally decades ahead of its time.

The Flying Brick

Yet it’s hard to think of a more unlikely basis for a modern road racer than the four-cylinder BMW K100 ‘Flying Brick’ – or a more unlikely person to create such a bike than Spanish GP chassis guru Antonio Cobas, who sadly passed away from cancer in 2004 at the age of 52. But that’s exactly what happened 40 years ago, when Cobas and his patron Jacinto ‘JJ’ Moriana decided to construct a BMW endurance racer using the engine of the then newly-launched four-cylinder K100 model which had debuted in the marketplace in 1983. Their aim was to win what was then Spain’s most prestigious road race, the classic Montjuic 24 Horas run in the heat of July through the streets of the hillside park in the centre of Barcelona, which in 1992 would provide the site for the Catalan capital to host the Olympic Games.

But in 1984, Montjuic meant only one thing: the opportunity for 100,000-plus bike-mad Catalans to spend a hot summer day and all of the night partying it up while watching the world’s top Endurance racers racing round and round (and round and round, for an entire day) their city’s parkland circuit, formerly host for many years to the Formula 1 and motorcycle Spanish GP races, before safety issues and politics caused both to be moved to Jarama, outside Madrid.

Their aim was to win what was then Spain’s most prestigious road race, the classic Montjuic 24 Horas…

This exposure to such a huge public, as well as the heavy TV coverage and intense press interest, was what persuaded Moriana to commission Cobas to build the bike – for as Barcelona’s biggest BMW car dealer, and the German marque’s largest motorcycle sales outlet in the whole of Spain, ‘JJ’ knew that building a Superbrick racer to promote the new K100 range would be good for business. You didn’t need to win the race (though that would be nice) – just be competitive and make a good showing with some newsworthy star riders aboard the bike.

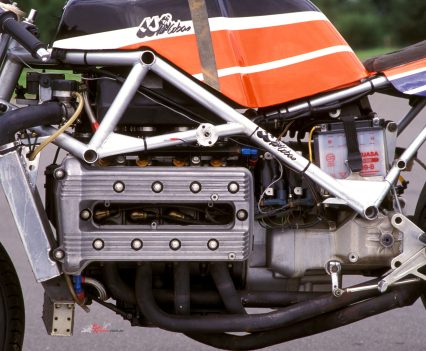

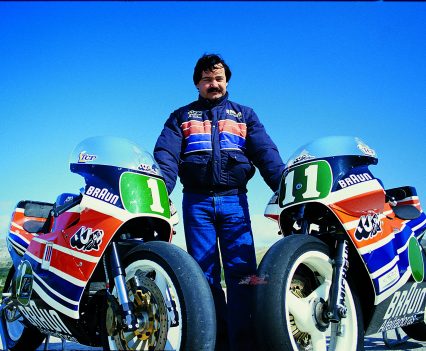

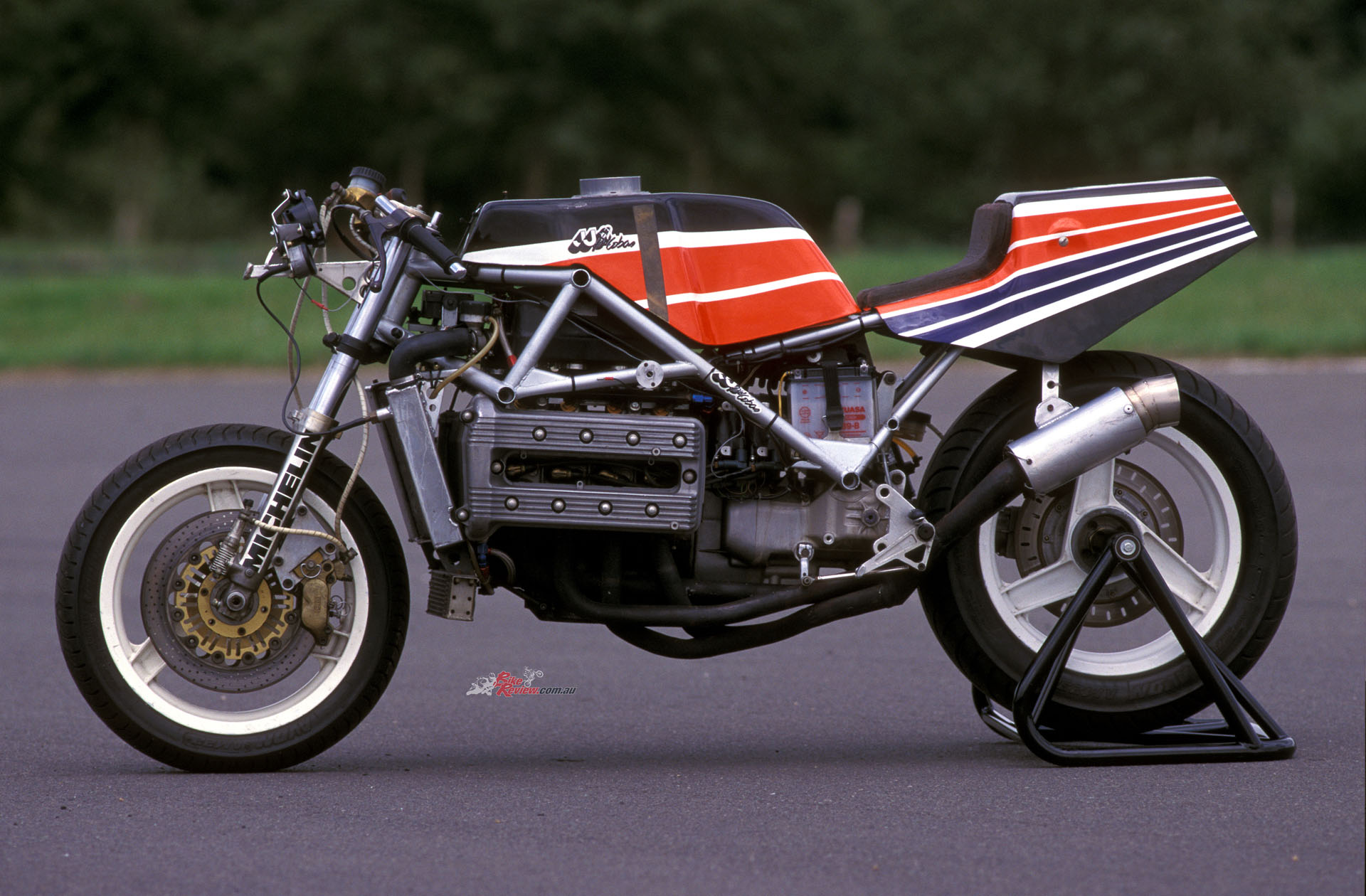

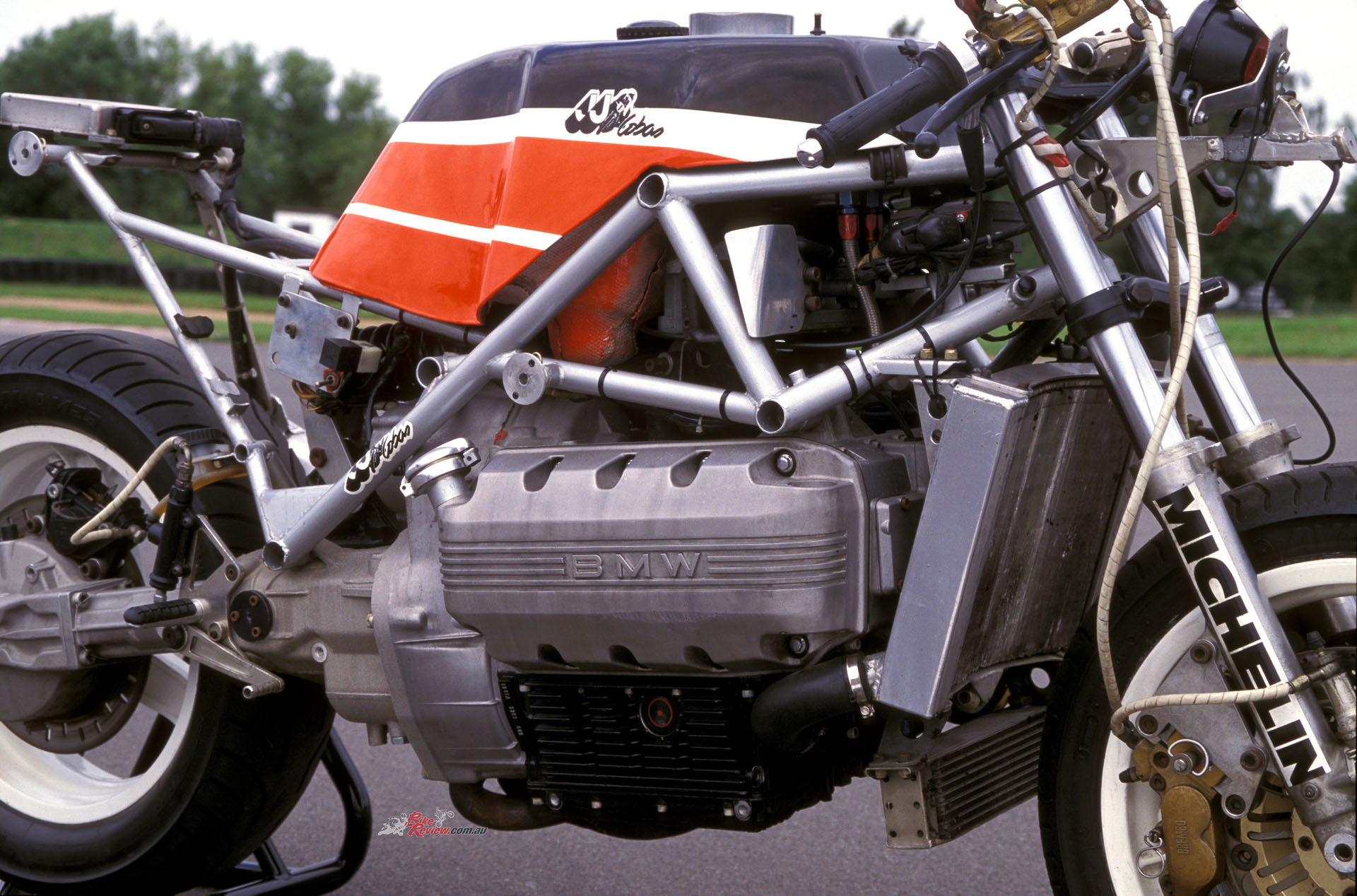

So that’s what happened. Moriana negotiated a deal with BMW Iberia for a pair of K100 engines, Braun Domestic Appliances was enlisted as an eager sponsor (bike racing was then second only to football in terms of sporting popularity in Spain), and Cobas set about the task of wrapping a frame round the hefty engine weighing a meaty 100kg complete with swingarm and drive shaft. For the man who three years previously with the first Kobas 250GP racer had invented the modern twin-spar aluminium GP chassis as we now know it, this was a challenge he relished.

But Antonio had good help in creating the SuperBrick, for in charge of engine development was Eduardo Giró, the man who in the late ’60s created the ground-breaking monocoque-framed works Ossa 250GP bike on which Santiago Herrero won four GP races and led the World Championship, before tragically losing his life in the Isle of Man TT.

Montjuic Marathon

But Giró was hamstrung in what he could do to the K100 by the BMW factory’s refusal to release the access codes for the Bosch fuel injection’s ECU – a fact which initially hindered development of the world’s first fuel-injected Superbike, because the EFI couldn’t be remapped to suit the tuned-up motor. Still, three months after the project kicked off, the first of the two JJ-Cobas BMWs to be built made its race debut in the hands of European 250GP Champion Carlos Cardús, finishing third in a round of the Spanish Superbike series at Jarama run to the same TT Formula 1 rules as the 24 Horas, permitting tuned streetbike engines in race chassis. A good start, but there was still lots to do before the Montjuic marathon just three weeks hence.

They ran out of time. The lead JJ-Cobas BMW, ridden by Cardús, future 250GP World champion Sito Pons, and former 24 Horas winner Quique de Juan, suffered continuous problems with the Bosch ECU, which the team had tried unsuccessfully to adapt to the tuned racing engine. After blowing all the spare boxes they had in the pits, the BMW was forced into ignominious retirement. The second bike, crewed by Moriana (himself a competent Endurance racer) and two friends didn’t suffer from the same problems, but was never well placed, and eventually crashed into retirement.

Two weeks later, in the aftermath of this well-reported debacle, two engineers from BMW Motorrad presented themselves at the doors of the JJ-Cobas team’s workshop, with their briefcases stacked with electronic hardware, and a brief to resolve the bike’s problems. Remember that the Cobas-BMW was the first racebike of the modern era, featuring an electronic engine management system which companies such as Bimota and Ducati would later adopt on their new-generation Superbikes, as is commonplace today. Two weeks hard work by the duo saw the problems corrected, and the longstroke 67 x 70mm 988cc engine now delivered 122 bhp reliably, at 9,400 rpm.

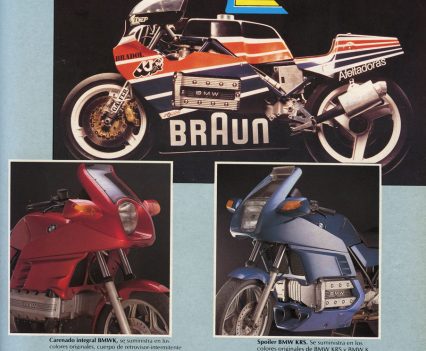

This was sufficient to allow the Cobas-BMW to dominate the balance of the 1984 Spanish Superbike Championship, with Cardús winning each of the six remaining rounds to convincingly win the Superbike crown, before the team invited me for an exclusive test ride on the bike at the tight, twisty Calafat track south of Barcelona, which places handling and braking at a premium. My test of the Superbrick helped create worldwide interest in it, so much so that BMW Motorrad management commissioned Bimota to work on developing a limited-edition street version. Although this project was sadly aborted – but its fruits resurfaced a decade later with the Bimota-developed K1000RS – the JJ-Cobas team’s success with the bike in sprint racing meant that they faced the 1985 Montjuic 24 Horas confident that, this time around, victory would be theirs.

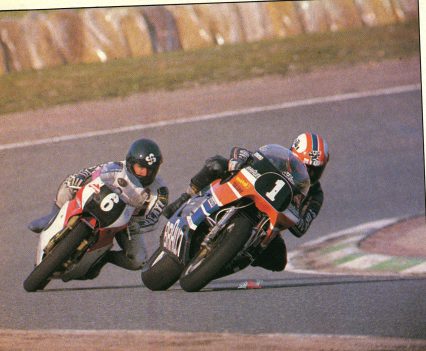

Sadly, such belief was ill-founded, with Cardús and Pons joined by another local GP ace, Luis Miguel Reyes, on a single bike which completed the first lap of the race in Cardús’ hands dead last in the 45-bike field, running very erratically. Incredibly, after qualifying in the top five, more electronic problems had surfaced, and while these were sorted well enough to let the BMW pull up to seventh place after six hours, Pons crashed the bike and the JJ-Cobas team lost half an hour making repairs in the pits. Cardús took over, but went too hard trying to make up time, crashing the BMW into retirement just three laps into his stint. End of story.

By now, JJ-Cobas had become top contenders for GP victory in the 250 and, later on, 125cc classes, so the BMW-powered Endurance racer was put away, while they concentrated on winning the 1989 World 125GP title with a young kid called Alex Crivillé riding their Rotax-powered JJ-Cobas single. But the sad early death of Jacinto Moriana not long after saw his superb collection of JJ-Cobas machines entrusted to Spain’s finest private motorcycle museum, the Colleciò Can Costa.

“They concentrated on winning the 1989 World 125GP title with a young kid called Alex Crivillé riding their Rotax-powered JJ-Cobas single”…

It was at the behest of its owner Joaquín Folch that I was asked to renew my hands-on acquaintance with the K100R Superbrick in the display of BMW bikes at the Goodwood Festival of Speed hillclimb – followed by a more intensive circuit test session at the Mallory Park track. If Goodwood was the hors d’oeuvres – Mallory was the main course!

Riding the K100 Racer

Riding the JJ-Cobas BMW again so many years later opened a window on a forgotten world of motorcycle development – the era of 16-inch wheels, when tyre companies and chassis designers hunted for more grip at both ends via wider rubber, coupled with tradeoff steering geometry featuring a wide fork angle and minimal trail, to try to get the result to steer reasonably quickly, while remaining relatively stable.

This was coupled with antidive front suspension to prevent said steering geometry altering unduly under heavy braking, and a forward weight bias to make sure that when you did brake hard, the front wheel stayed glued to the ground via the wider footprint of the 16-inch tyre. It all sounded plausible and to a certain extent it still works OK today – I certainly never rode any bike, even a smaller and more agile Supermono single, which flicked from side to side as improbably quickly through the tight Mallory chicane as the Cobas-BMW.

“I certainly never rode any bike, even a smaller and more agile Supermono single, which flicked from side to side as improbably quickly through the tight Mallory chicane as the Cobas-BMW”…

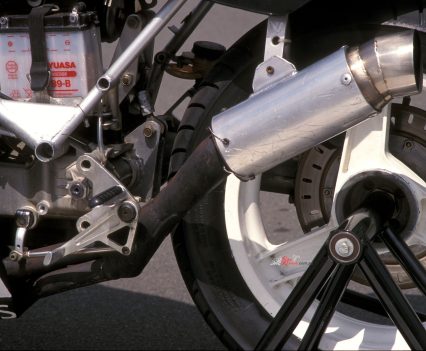

Relatively small and compact for a one-litre racer, the Cobas-BMW’s chrome-moly tubular steel spaceframe weighs only 6.0kg, with the DOHC in-line four-cylinder engine suspended horizontally from it, and acting as a fully-stressed chassis member. Cobas retained the stock BMW Monolever shaft final drive casing with its single-sided rear wheel – some years before Honda adopted the similar ELF-derived system on the RC30 – which offered added convenience for Endurance racing quickchanges, while designing his own progressive rate linkage for the single DeCarbon rear shock. Up front, the 40mm Kayaba fork with hydraulic anti-dive sourced from an RG500 Suzuki GP bike is fitted, with a 16-inch Marvic wheel and 300mm Brembo brakes.

The street K100’s stock rear brake is retained, while the 18-inch rear wheel originally used on the bike was replaced for Montjuic 1985 by a 16-incher. New rubber in this unusual period size is notoriously hard to come by nowadays, but Avon came up trumps for Goodwood with race-compound treaded tyres that probably have as much grip or better than slicks of back then. Wheelbase is 1445mm – acceptably short, in view of the lengthways 67 x 70 mm longstroke engine configuration – with 53/47% weight distribution, a forward weight bias which Cobas was one of the first to explore, but we nowadays take for granted. The complete JJ-Cobas BMW scaled 179kg ready to race in Superbike form, as it is today – 185kg with lights and a larger battery etc. ready for Montjuic.

“The complete JJ-Cobas BMW scaled 179kg ready to race in Superbike form”…

The riding position felt a bit strange to start with, because you sit quite far forward in order to load up the front wheel still further with your body weight, which in turn leaves a good part of this on your arms and shoulders. That’s not ideal for Endurance racing, but the bulky 24-litre fuel tank nestles nicely into your chest and takes a good deal of the strain off your upper body. Fire up the motor on the button, and it immediately settles into a lusty, lumpy throb, that’s exactly like the sound of a Formula 3 racing car.

“The riding position felt a bit strange to start with, because you sit quite far forward in order to load up the front wheel”…

Quite quick-steering and relatively agile for a bike with such an improbable engine architecture, the Cobas-BMW was easy to chuck through tight turns like the Mallory chicane or the Goodwood Stable complex, but it also held a line well in fast sweepers like Gerards or the Esses at Mallory, where I could feel the progressive rate response of the quite softly sprung DeCarbon rear shock‘s linkage ironing out the bumps in the track surface. Remember the Montjuic Park circuit was a heavily travelled public roads circuit, so came complete with the lumps and bumps of everyday use.

Though seemingly rather high in the frame, hence the excellent ground clearance which allows you to max out the grip from the 16-inch Avons, and use a lot of angle in maintaining corner speed, the engine’s location results in a bike that makes the transition from upright to full lean quickly but smoothly. The Cobas-BMW didn’t knife edge into the turn like some big four-strokes with heavy in-line motors do, and the longtitudinal crankshaft and shaft drive – though bereft of BMW’s later Paralever solution – didn’t seem to result in any strange handling quirks, either. The combination of the quite rangy wheelbase and raked-out 27.5 degree head angle made for a bike that’s pretty stable in faster turns, yet feels reasonably nimble in tighter ones.

Less satisfactory was the JJ-Cobas BMW’s behaviour under braking, where the smallish 300mm Brembo discs do a surprisingly good job of hauling the bike down from high speed, despite the fact that there’s little weight transfer, thanks to the Kayaba fork’s hydraulic antidive. This means the bike brakes very flat – a bit like a hub-centre Bimota Tesi of the same era – plus it takes all your strength pressing hard down on the opposite ‘bar to stop the BMW sitting up under braking, and heading for the hedges as it understeers off-line.

Several factors are to blame for this distinctive mid-‘80s handling quirk: the 16-inch front wheel, the rangy steering geometry, and the hydraulic anti-dive being probably set up much too hard. Moving the adjustable clipon handlebars out and down gave a bit more physical leverage, but it’s still a trait you have to watch out for – you can’t go trailbraking into a turn, else you risk missing the apex so that by the time you get it turned, you’ll be late on the gas for the drive out. Instead, you have to ride it like driving a car, and do all your stopping in a straight line, before chucking the JJ-Cobas into a bend on its side with your fingers off the brake lever and the throttle already primed, then feed in the power gradually as the turn opens up.

“You have to ride it like driving a car, and do all your stopping in a straight line, before chucking the JJ-Cobas into a bend on its side”…

The extremely linear power delivery from the smooth-action engine is your key to making this work OK – really, riding the Cobas-BMW 40 years ago was the ticket to the promised land of EFI which Ducati especially made us take for granted in later years. Back then, Eduardo Giró’s work on the engine concentrated on increasing power, without sacrificing flexibility. Varianti Colombo in Italy came up with a set of racing camshafts for the JJ-Cobas team, which raised power from the street K100’s 90 bhp up to 108 bhp in race guise – the rest came from the German BMW engineers’ reprogrammed EFI, combining with an 11:1 compression to produce 122 bhp at 9,400 rpm. No attempt was made to lighten the crank or otherwise modify the bottom end, but the standard pistons have been relieved on the crowns to give more clearance with the greater overlap delivered by the racing camshafts.

“No attempt was made to lighten the crank or otherwise modify the bottom end, but the standard pistons have been relieved on the crowns”…

Giró also extensively ported and flowed the cylinder head, retaining however the standard valves (just two per cylinder) and springs, resisting the temptation to fit carburettors, so retaining the Bosch Multipoint EFI and the greater management control it offers. Fine tuning of this is accomplished by adjusting the screw on the metering unit located atop the cylinder block, and changing the entire EFI black box for one with a greater or lesser resistance.

“Fine tuning of this is accomplished by adjusting the screw on the metering unit located atop the cylinder block”…

This in turn gives richer or weaker mixture – the detachable EPROM chips which had the same effect on Bimota and Ducati Superbikes a couple of years later hadn’t yet been invented. The JJ-Cobas team’s standard unit as fitted to the bike both times I rode it was a ‘minus 10’ (percent, from standard in terms of mixture strength), but they had also ‘minus 5 and 15 and ‘plus 5’ units donated to them after Montjuich, all with a different array of diodes giving alternative carburation.

“The Cobas-BMW starts to produce very usable horsepower just as the needle on the Scitsu tacho hits the 4,000 rpm mark”…

The effect of this back when I first came to test the bike at Calafat so long ago was literally a revelation: until then, I’d never ridden a racing bike which had a smoother power delivery from practically zero revs, or a crisper, more immediate throttle response and pickup. One lap at Calafat made me a believer in fuel injection – but it was only with Ducati’s arrival on the scene with their desmoquattro, that this became commonplace in racing. In fact, the Cobas-BMW starts to produce very usable horsepower just as the needle on the Scitsu tacho hits the 4,000 rpm mark, then keeps building progressively and quite quickly up to the 9,400 rpm power peak and beyond.

This is all without the slightest dip in that incredibly flat torque curve, nor a splutter from the Giró-designed exhaust – although there’s a noticeable increase in vibration at higher revs. However, even for a short circuit like Mallory Park, the BMW was undergeared, forcing me to back off the throttle of the longstroke motor at 10,000 rpm in top (fifth) gear down the pit straight. The JJ-Cobas team had a choice of six final drive cardan units offering alternative overall ratios, but the one fitted to the bike in its retirement from the racetrack must have been the one for Calafat – a VERY short circuit, indeed!

The single-plate diaphragm clutch is incredibly light – you can operate it with your little finger – but another surprise came when I tried changing gear upwards without using it. On other shaft-drive racers like Guzzis and BMW Boxers, that’s Not a Good Idea, and even less a one is to knock the power off in the middle of a corner, and feel the dreaded understeer take over as the rear end drops a couple of inches, bringing ground clearance problems in its wake. The K100-powered JJ-Cobas racer is almost completely free of these vices, though there was some noticeable torque reaction changing down from second to bottom for the Mallory hairpin, and a big thump from the transmission going in the other direction changing into second without the clutch – so you must use it.

All the more reason to relish the K100 engine’s flexibility, and avoid the use of bottom gear except off the line, because otherwise the bike was as well-mannered as any chain-driven two-wheeler – it didn’t even pull the old BMW trick of rising up and down on the suspension as you changed gear. Even so, I still needed to use bottom gear for the Mallory hairpin, and while the one-down street-pattern gearchange has a good action, hitting it under braking made the back wheel chatter under reverse engine loads. This bike really needs a slipper clutch, so without one it’s better to notch first gear just as you lean into the turn, then drive on out just as if you were leaving a traffic light.

To begin with, the JJ-Cobas team experimented with using the stock gear ratios, but by then Giró had only managed to extract 102 bhp from the engine, and moreover usable horsepower was only available from 6,000 rpm upwards – it was in this form that the bikes ran at Montjuich in 1984, when they must have been a bit revvy to ride hard for 24 hours. This exposed the gaps in the standard cluster, so Giró had a close-ratio set made with the racing bottom gear now higher that the streetbike second, but retaining the original top gear ratio. It’s a nice gearbox, even if bottom gear could still be even higher.

Though the success in the Montjuic 24 Horas that it was really built for was never achieved, Carlos Cardús’ victory in the Spanish Superbike race series proved the JJ-Cobas BMW had the Right Stuff. It’s a pity that BMW Motorrad never went ahead with its plans to put the bike into limited production in street form – but the untimely death at a youthful age of Stefan Pachernegg, the BMW Motorrad director who actively promoted this option, and had succeeded in getting it approved in principle by the rest of the BMW AG board, put an end to the idea. BMW Motorrad really should have made more of the JJ-Cobas K100 than it actually did – but the bike exists today in the Colecciò Can Costa to show us what might have been, as a milestone in motorcycle evolution.

“For this is in fact the first-ever racing motorcycle fitted with electronic fuel injection and a computerised engine management system”…

For this is in fact the first-ever racing motorcycle fitted with electronic fuel injection and a computerised engine management system, two years before the first such Ducati appeared in 1986. And that somewhat improbably makes the JJ-Cobas BMW not only the first step along the German manufacturer’s path to its first World Superbike crown courtesy of Toprak Razgatlioglu, but also the first four-stroke racebike of the modern era – Made in Spain 40 years ago this year, with a little help from Germany!

JJ-COBAS BMW K100R Superbike Specifications

Engine: Water-cooled, four-cylinder longitudinal (noth-south) eight-valve DOHC four-stroke with offset camchain, 67 x 70m bore x stroke, 987cc, 11:1 compression, EFI with Bosch EMS and ECU, single injector per cylinder, five-speed gearbox, single-plate clutch, shaft drive.

Chassis: Tubular steel spaceframe with engine as fully stressed member, 40mm KAYABA forks with hydraulic anti-dive, Monolever cast-aluminium single-sided swingarm with DeCarbon monoshock and rising rate linkage. 27.5º rake, 53/47º static weight bias, 1440mm wheelbase, dual 300mm Brembo cast iron rotors with four-piston four-pad Brembo calipers (f), single 280mm Brembo steel rotor with two-piston Brembo caliper (r), Brembo master-cylinder, cast alloy Marvic wheels, 3.50 and 5.00 x 16in, 120/70 – 16 and 180/60 – 16 Avon AM22/AM23 tyres.

Performance: 122hp@9400rpm at rear wheel, 179kg with oil/water no fuel, top speed 278km/h. Owner: Collecio Can Costa, Barcelona, Spain.