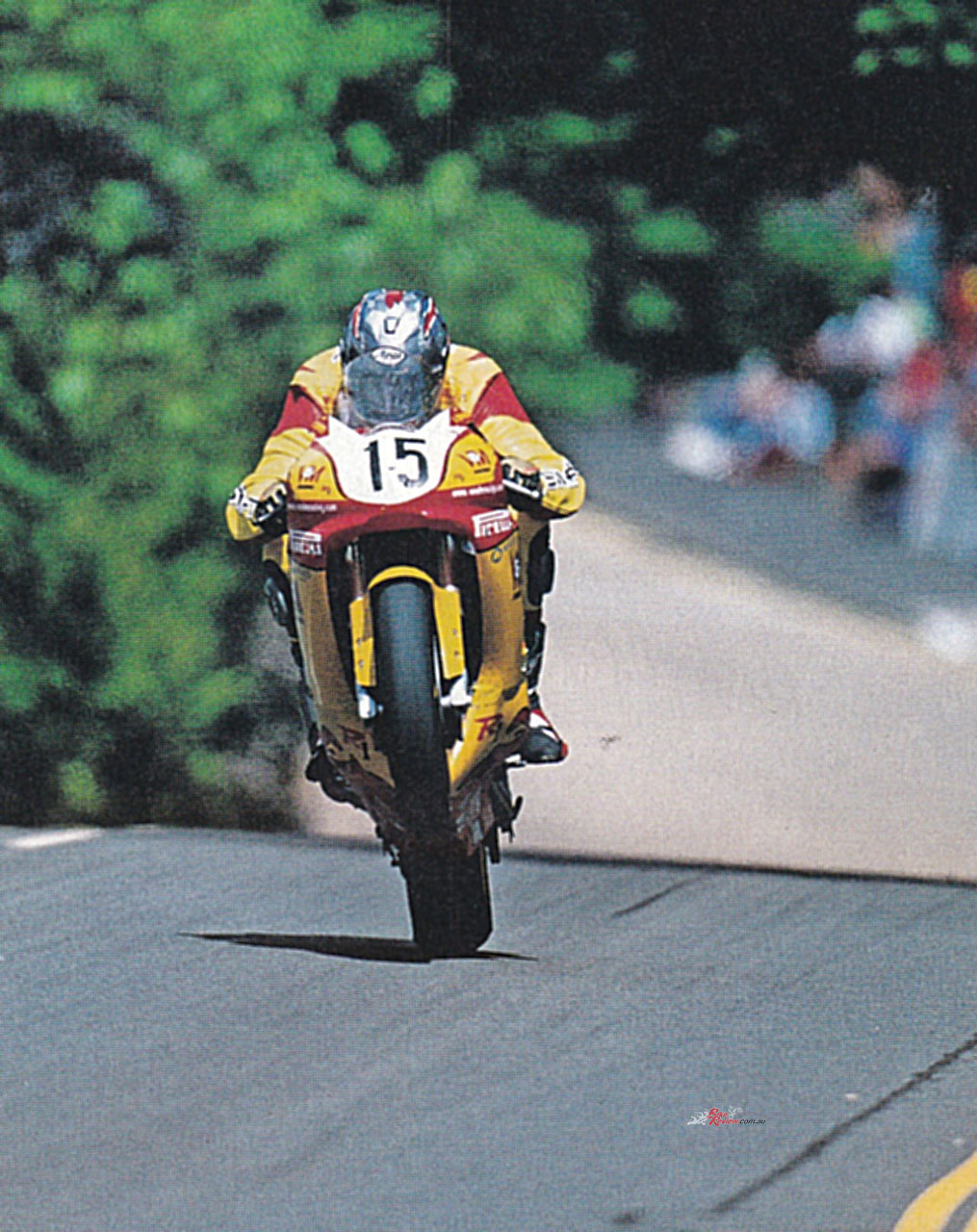

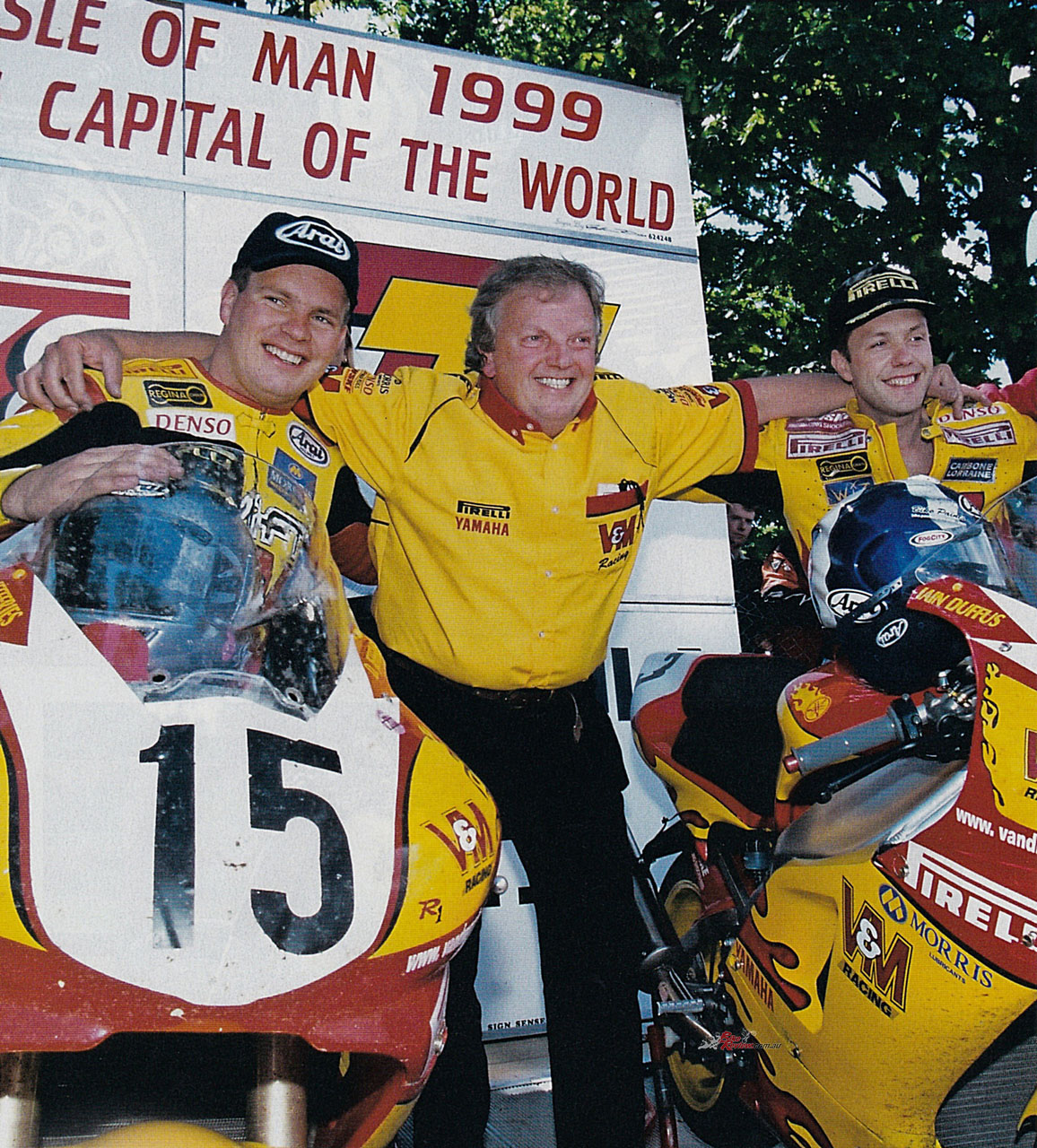

25-years ago David Jefferies and this bright yellow and red V&M Racing YZF-R1 became global racing superstars. Sir Al had the pleasure of test riding the bike. Photos: Kel Edge/AC Archives

The October 1997 debut of Yamaha’s YZF-R1 put the Japanese company at the leading edge of sportbike design – a position for which it’s been in contention ever since reinventing the modern four-cylinder Superbike with the advent of the original R1 for the 1998 model year.

With the architecture of its trademark five-valves-per-cylinder in-line four-cylinder 998cc motor completely redesigned to compact its mass by stacking the gearbox shafts one above the other, the consequent much shorter engine package allowed the wheelbase to be shortened significantly and a much longer swingarm fitted, resulting in improved traction, quicker handling and an enhanced forward weight bias, plus an optimised cee of gee.

Read Alan’s other Throwback Thursday articles here…

Yet Yamaha was initially unable to demonstrate the worth of its new technical format on the racetrack for the simple reason that, back then, Superbike racing had a 750cc top limit for four-cylinder bikes – meaning that there was originally only one place for a one-litre ultrabike like the new R1 to demonstrate its worth in competition – and that was on the roads.

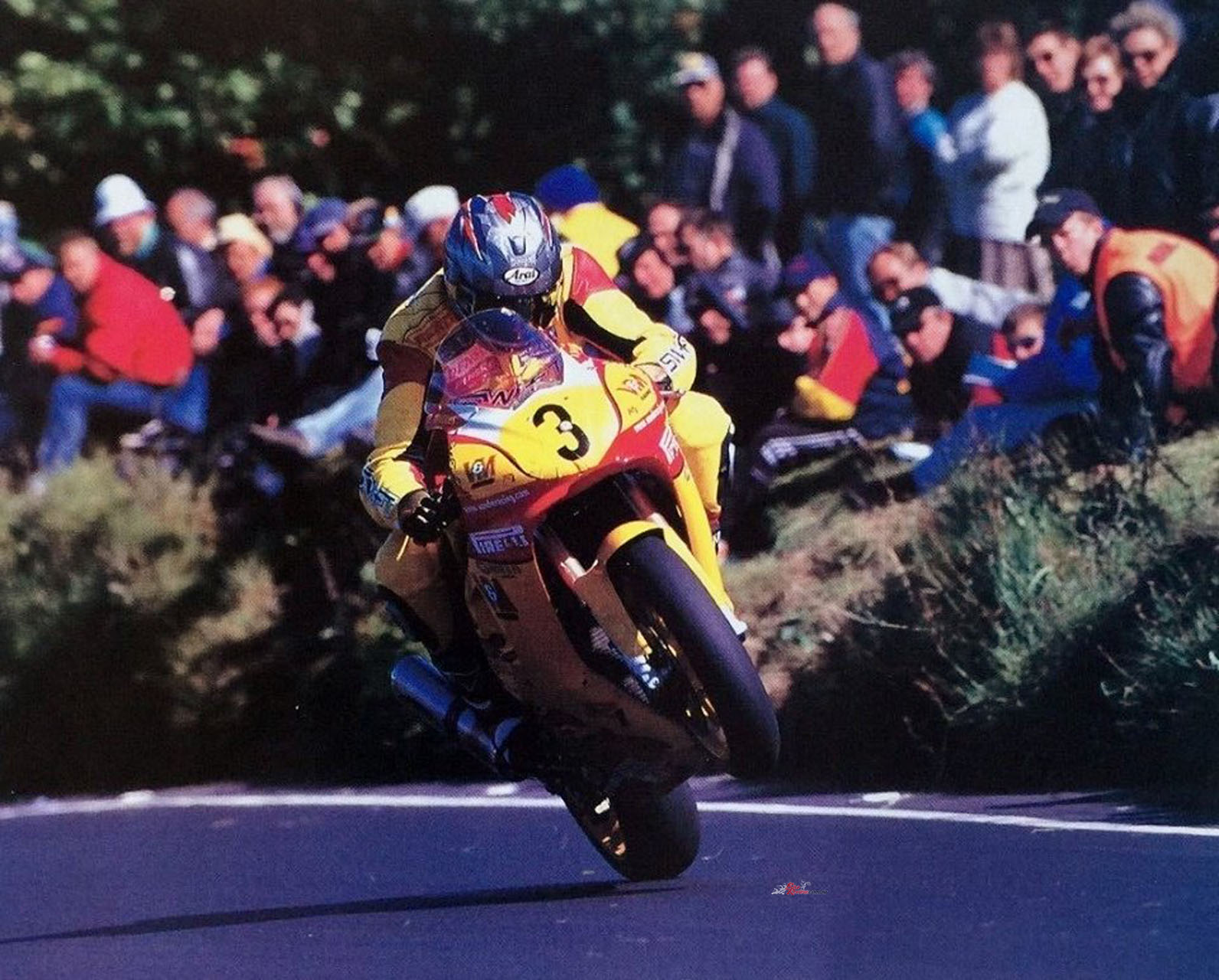

There, any remaining doubts that Yamaha’s R1 represented the new benchmark in ultrasports motorcycling were dispelled by the 1999-season performances of Yorkshire’s late, great David Jefferies, on the modified R1 streetbike honed by Britain’s top tuning house V&M Racing into the undisputed King of the Roads. For in the final race season of the 20th century, the 26-year old son of a famous father – DJ’s dad was factory Triumph rider Tony Jefferies, himself a TT winner in his own right – completed an unprecedented clean sweep of all the world’s greatest and fastest public roads races aboard the V&M Yamaha, first winning the North West 200 – Ireland’s best attended sporting event of any kind, attracting over 100,000 spectators.

David then won both the Formula 1 and Senior TT races in the Isle of Man, the Ulster GP at Dundrod, and finally the last Macau GP to be run on the shores of the South China Sea, before the Portuguese colony reverted to China at the end of that year. In practice for the Ulster Grand Prix, David Jeffries put the V&M R1 on pole position wearing an orange Newcomer’s bib – ahead of local legend Joey Dunlop on a full works Honda RC45, whom he then defeated to win the first Superbike race held that year on the Dundrod circuit.

In many of these races, David was followed home by his Scots team-mate Iain Duffus on a second V&M R1, while in both Irish events he set a new outright lap record. In the case of the Dundrod track’s 126.86 mph mark, this was then the world’s fastest closed-circuit lap record for a track in current use – by a newcomer, on a course he’d never seen before! Finally, in each of these races Jefferies defeated not only a stern challenge from current 500GP two-strokes, but also the might of the works Honda team aboard their hyper-expensive tricked-out factory-built RC45 Superbike racers from a company which had dominated racing on the public roads for the best part of two decades.

“This was then the world’s fastest closed-circuit lap record for a track in current use – by a newcomer, on a course he’d never seen before!“

In the IoM TT, for example, Honda had won the Formula 1 race for an unprecedented 17 straight years, until the advent of the V&M Yamaha R1 brought that to an end, relegating TT-meister Joey Dunlop to second place on his works RC45. And all this with a modified streetbike which, eight weeks before its first race, was wearing a licence plate and tax disc. Impressive, no?!

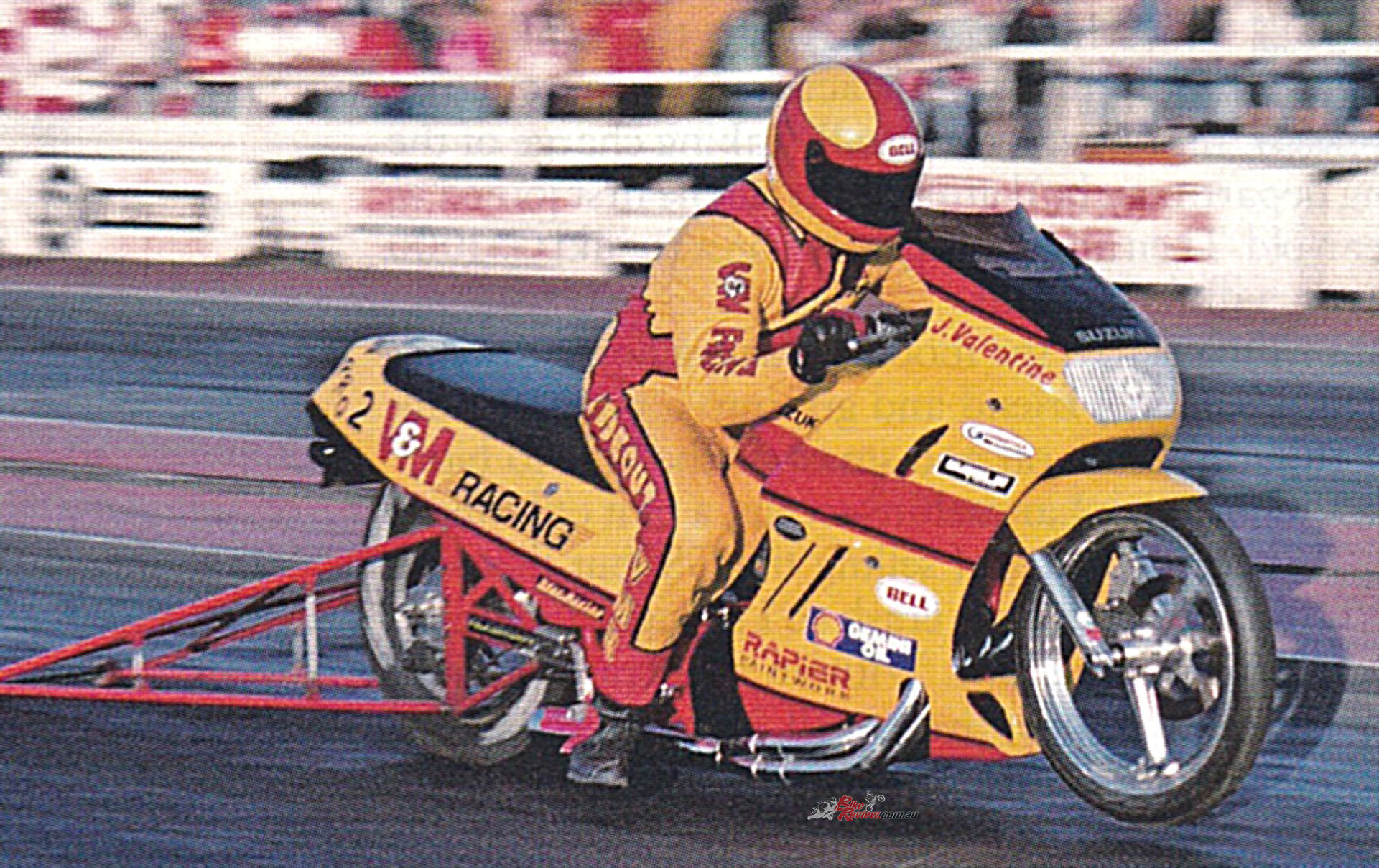

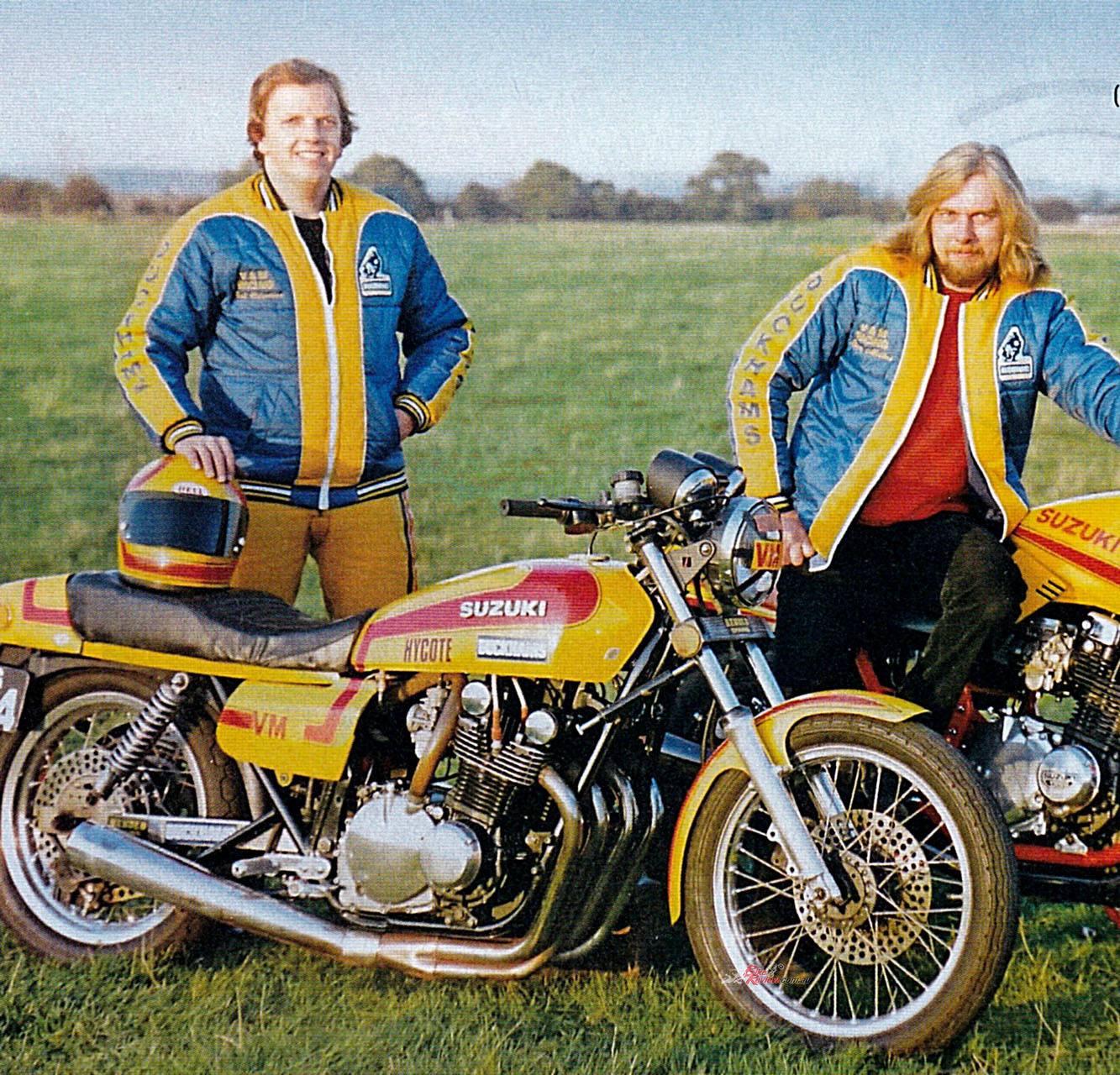

Manchester-based V&M Racing’s proprietors Jack Valentine and the late Steve Mellor were the exact British counterparts of America’s famed Vance & Hines tuning duo – and not just because V&M were by no coincidence V&H’s British distributors. Like Byron Hines, Mellor was an engine wizard adept at extracting unlikely amounts of horsepower from normally aspirated (non-turbo, unsupercharged) four-stroke engines – a skill which found due reward with the three European drag racing titles and several British crowns his partner Valentine won riding V&M bikes during numerous years in the Euro drag leagues, just as V&H rider Terry Vance was doing Stateside.

After founding V&M back in 1983, the two partners carved an enviable reputation as Britain’s top performance shop, tuning streetbikes for Joe Public as well as road racing motors for the likes of the UK Kawasaki and Yamaha importer teams, before going road racing themselves. They duly linked with Honda to win countless Isle of Man TT races and a quartet of British Supersport crowns during the 1990s, before a disagreement with Honda Britain midway through the 1998 season put an end to that.

After founding V&M back in 1983, the two partners carved an enviable reputation as Britain’s top performance shop…

But even by their already illustrious standards, nothing the two partners had raced before ever earned the ‘V&M for Victory’ tag quite as emphatically as the Yamaha R1 which David Jefferies won so many races aboard in 1999, heading for Victory Lane straight off the showroom floor via a vital pitstop in Steve Mellor’s workshop, to be transformed into a dominant racebike.

“Nothing the two partners had raced before ever earned the ‘V&M for Victory’ tag quite as emphatically as the R1″…

It was an added irony that, when Valentine and Mellor decided to hit the roads in ‘99 with the new Yamaha maxibike, David Jefferies was very much second on their shopping list of riders, behind proven TT expert Iain Duffus. “But we knew we wanted to have a two-man team, and David was the obvious choice,” recalls Valentine, whose 30 years in team management saw him also running factory supported teams in BSB and/or World Superbike for Triumph, MV Agusta, Suzuki, Honda Kawasaki and Foggy Petronas.

“He’d only ridden in the Island for two years, but was already a top-six finisher and had lapped at nearly 120 mph in a Proddie bike, which showed he knew how to ride big bikes hard. He’d lost his way in racing a bit, considering that at age 19 he was scoring points in World Superbike races – but we reckoned that with the right bike and good support from the team, he’d come good. I would say he did that – wouldn’t you?!”

Too right – although as my chance to ride the V&M R1 at Donington Park, fresh from DJ’s world’s fastest lap record-breaking victory sortie in the Ulster GP, confirmed, he did have a bit of help from his equipment. For even to someone used to track testing each successive season’s complete menu of factory World Superbike entries, let alone the first-ever R1 Superbike, the Mihara R1 Yamaha that by then was a points-scoring contender in the Japanese Superbike Championship against all the factory team bikes, Jack ‘n’ Steve’s once-a-streetbike road racer was an incredibly impressive piece of kit – as well as a devil in disguise.

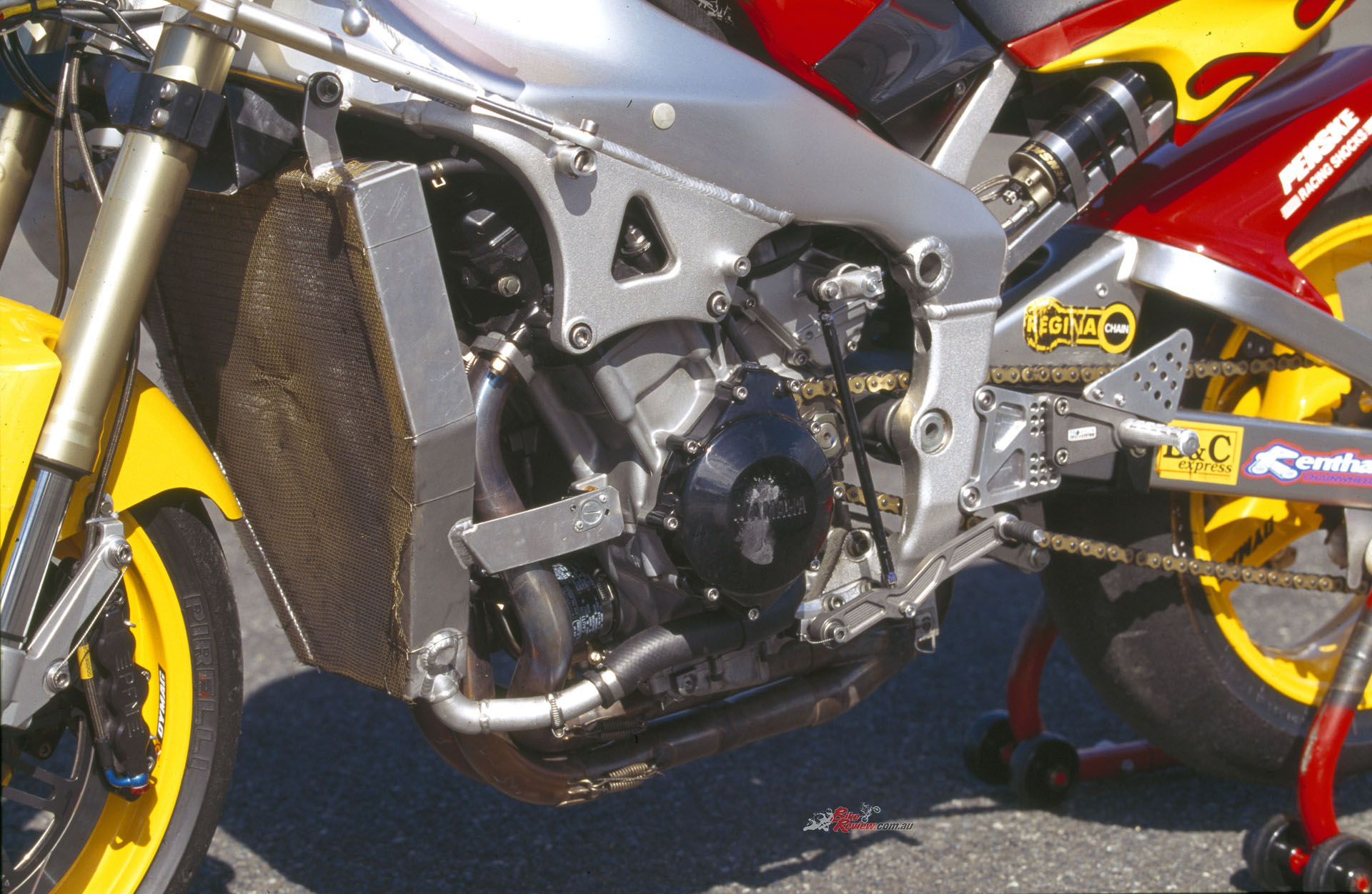

I mean, try and ignore the strident red and yellow paint scheme (difficult: best wear sunglasses to look at it in daylight!) – and the bike I was about to sling a leg over just looked so, well, normal. That’s because it was: chassis, front suspension, bodywork and swingarm were all streetstock items, with only the domed screen which gave the kind of wind and bug protection street R1 riders could only dream of, providing a clue to what this bike represented. Oh, that and the slightly taller fuel tank, whose extra capacity had been cleverly grafted on top without disturbing the shape overmuch. It did make you feel more ensconced within the bike than a stock R1, though – not so much perched on top, with precious little aerodynamic protection from the streetbike’s vestigial screen, as on the street R1s that I’d by then become used to riding.

It was still a pretty close-coupled package, though – more maxi-GP racer than one-litre streetbike, albeit with lots of space to tuck behind the screen in a straight line. Well, so long as you weren’t standing on the footrests trying to heave your body weight forward to try to persuade the front Pirelli tyre to resume contact with mother earth, without your backing off the throttle. In fourth gear!! More than any World Superbike I’d yet ridden, the V&M R1 was a motorcycle on which you absolutely, emphatically, had to make sure you sat as far forward on the seat as you possibly could when dialling up power out of a turn, else you’d make a fair stab at doing a Mamola and looping the loop just like Randy did that time at Assen on the works 500GP Cagiva – except he was showboating and it all went wrong, and you’d be trying to ride the Yamaha right, and get it wronger still.

“More than any World Superbike I’d yet ridden, the V&M R1 was a motorcycle on which you absolutely, emphatically, had to make sure you sat as far forward on the seat as you possibly could!”

The cause of all this was down to the Mellor magic in tuning the 20-valve slantblock Yamaha streetbike motor [see Technical sidebar] to deliver a level of performance that some 750cc factory Superbikes could only dream of back then – yet without sacrificing rideability on an engine which pulled from way low, just like a streetbike, only much, MUCH stronger. Quite the contrary: you had to shortshift accelerating through the gears and ride the meaty torque curve rather than rev it right out looking for maximum power, simply in order to be able to point the bike where you wanted it to go in those pre-electronic days with no traction control, and especially no anti-wheelie control.

“so much power all the way through the rev range – and especially when you got it revving above 8,000rpm”…

Don’t think I’m exaggerating: once you got the V&M R1 motor pulling any higher than the 4,000rpm mark at which meaningful power began, the fastest way from A to B was not by screaming the engine in the gears, and making the muted but musical Akrapovič exhaust utter its haunting, high-pitched message at peak revs – but by riding the torque curve, and revelling in the R1 motor’s muscular magic. That’s because there was so much power all the way through the rev range – and especially when you got it revving above 8,000 rpm, where there was an extra dose of punch – that you could even get lazy, and cut down on gearshifting.

This was especially so with the tall Ulster gearing fitted for my test, which meant I grabbed a genuine fifth gear for just a nano-second going over the wheelie launch pad under Donington’s Dunlop bridge, before braking hard for the Foggy Chicane and kicking it down a few gears, having deliberately shortshifted to try and tame the monster 120 mph wheelie it pulled there every lap – sixth gear was out of the question at Donington Park, on a bike geared for 190 mph in top!

In fact, I tried riding Donington both ways, revving it to the 12,000 rpm power peak in every gear, indicated by the green/amber/red trio of shifter lights on the very clear-reading Spa Design tacho (the revlimiter came in at 12,500 rpm, but there was no point in hitting it, with so much punch lower down), and then cutting a handful of even quicker laps by riding the torque curve and not downshifting for turns, except at the last trio of slow bends where the engine pulled cleanly and controllably away in second gear – accompanied by what had now become the usual spate of wheelies.

There were three reasons why lazy was best – leastways, at Donington. Firstly, the gearchange on the V&M R1 felt just as harsh and mechanical as on the stock first-series R1 streetbike – not only going through neutral between first and second (another reason to ride the torque curve), but in the higher gears as well. Though the later 2000-model R1 had a much improved action, on this older one you didn’t want to use the gearbox unless you had to – especially on a short circuit, and with no wide-open powershifter fitted. Second, the Pirelli slicks ridden by DJ to his succession of victories were great for road circuits, where you wanted a tyre that would last two laps of the TT Course, as the Pirellis did, or 40-odd minutes of flat-out motoring, without giving up the ghost.

“The front tyre felt fine, within the limits of the corner speed I was brave enough to keep up – that’s when it was actually touching the ground, of course”…

This isn’t a course where you want to gamble on tyre choice, and in that pre-TC era risk losing grip in the middle of a fourth-gear 120 mph turn with a stone wall or mountain precipice on the outside. In those days before they became the World Superbike control tyre, the Pirellis were fine for this – but not so good using lots of repeated angle hard on the gas on a GP short circuit. So as I speeded up as I began getting the hang of riding the bike, I felt the rear tyre repeatedly start to walk on me at places like McLeans and Coppice, let alone Redgate. The front tyre felt fine, within the limits of the corner speed I was brave enough to keep up – that’s when it was actually touching the ground, of course – but all that horsepower needed more suitable rubber for short circuit delivery. It would be another four years before Pirelli developed such a tyre for World Superbike competition…..

But the final reason was one of physique – because one reason David Jefferies was able to tame the V&M R1 so effectively is because he was a pretty burly guy, who used his build to best advantage in forcing the wheel down and the bike pointing straight ahead under hard acceleration. It still didn’t stop him being photographed pulling fifth gear wheelies at 140 mph through Kirkmichael village, mind – but at least he was able to show the bike who’s boss.

Kevin Curtain (#1) won many Australian Superbike Titles on the Yamaha YZF-R1, as Australian embraced 1000cc rules from 1999 onwards.

Mind you, it did mean the team had to stiffen up the suspension and dial in some extra ride height on his bike, to stop the bellypan skating him into the haybales when it bottomed out at jumps like at Ballaugh Bridge or Ballacrye, with his extra kilos. Though David showed he wasn’t just a big bike rider by his series of wins and rostrum finishes on the V&M R6 Supersport 600, it did help being beefy to get the best out of the R1 racer. Pass the pasta, pet – I need second helpings to try to get up to fighting weight for the arm-wrestling close combat that trying to master the King of the Roads entails…!

Another reason to chase added kilos, or at least extra beef, was to muscle the Yamaha round a tight section of track like most of Donington, where you’re constantly changing direction from side to side, just as in the slow city section up through the residential hills of Macau. It wasn’t unduly heavy-steering – but nor was it a Superbike, either, thanks to V&M’s deliberate choice to dial in extra trail for added stability. The R1 didn’t understeer on the power as much as I expected it would as a result of that, but it did need quite some effort to lift it up and over from side to side, like sweeping down Donington’s Craner Curves, and it tended to fall on its side a little in a typically slow short circuit turn, like the chicane. But this would be a small penalty to pay for the extra high speed stability V&M had dialled in with their altered steering geometry.

“Rather surprisingly the PFM cast iron brakes felt a bit dead, needing a good hard squeeze to stop the Yamaha for the chicane, or Melbourne Loop.”

Rather surprisingly the PFM cast iron brakes felt a bit dead, needing a good hard squeeze to stop the Yamaha for the chicane, or Melbourne Loop. Probably that’s because of using harder-compound pads which must last a two-hour race at 120 mph average speeds – because when I raced the Saxon Triumph in 1995-96 fitted with the same PFM cast-iron brake package, these had magical bite and added sensitivity to stopping power, as well as working great in the rain. Coupled with the SaxTrak front end, it wasn’t often I got outbraked into a turn in a Thunderbike race on that bike, and I bet one reason DJ liked the British six-pot stoppers was because they were always bound to work as well as the end of a race as they did at the start.

Thanks to Jack Valentine and Steve Mellor, I had my perception of what Superbike racing is really all about irrevocably changed by riding DJ’s R1. The V&M Yamaha was the modern-day equivalent of those Yoshimura Z1 Kawasakis of the mid-’70s, volume-production streetbikes which Pops tuned to blazes, made halfway decent handling within the limits of the stock frame, then went looking for riders brave and skilled enough to wrestle them to victory in spectacular, crowd-pleasing style.

With campaigning already well under way for a one-litre Superbike limit across the board, the V&M R1 provided a window on the future World Superbike world – even though it took exactly ten more years for Ben Spies to finally give Yamaha their first World Superbike crown in 2009, breaking their duck as the only Japanese factory never to have won the title – albeit with a very different kind of R1 Superbike than this V&M Yamaha of a decade earlier. For with today’s 1000cc Superbike four-cylinder format, remember where it all started out, and which hypertuned streetbike was the first to lick Honda’s four-stroke 750cc GP-racers-aka-Superbikes, landing a telling and repeated blow for the small, specialist tuning house against the might of a Japanese factory race team.

But sadly, David Jefferies never got to see that happen. Instead, in 2000 he returned to win three more races on V&M Yamahas – but this time on the so-called R71, a brand new bike concocted by the team shoehorning a tuned R1 moor into a modified R7 frame – and with no races in a 2001 season blighted by foot-and-mouth disease, it was only in 2002 that DJ returned to the Island, now riding for the TAS Suzuki team, to make it a hat-trick of TT hat-tricks by winning three TT races again, for the third year in succession, in the process setting a new absolute TT lap record of 127.30mph. But tragically, the following year, on May 29, 2003, David Jefferies was killed instantly at Crosby, when his Suzuki GSX-R1000 hit someone else’s oil patch at high speed, and he was catapulted into a stone wall. DJ was just 30 years old, and he’ll always be remembered for his exploits on the V&M Yamaha R1 – the first Superbike of the current era.

V&M YAMAHA R1 TECHNICAL: Stripped-Out Streetbike Turned TT Titan

V&M’s decision to return to the Isle of Man in 1999 after a one-year absence with a stripped-out streetbike that would humble mighty Honda, came very late and almost by default, recalls Jack Valentine. “After we and Honda went our separate ways, we didn’t have the budget to do the British Superbike Championship, which was our first choice,” he says. “So we decided instead to concentrate on the public roads events like the TT and Ulster GP. That meant looking around to see what bikes we thought would be winners, and with the Isle of Man having gone back to the old 1000cc limit for the Formula 1 and Senior TTs, there was only one choice, the Yamaha R1. It had already done quick laps in Production guise, so my partner Steve [Mellor] knew he could build a very competitive racer.”

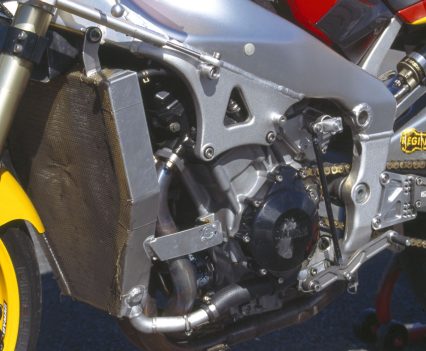

Getting hold of a pair of bikes to do that with was another matter, though, owing to stiff customer demand for the R1. But with just a little help from Yamaha they eventually sourced a couple just eight weeks before the team’s debut race in Ireland at the North West 200 in May – itself only a fortnight before the start of TT practice! Steve Mellor then set to work in V&M’s workshop just outside Manchester. Taking each in turn of the two standard R1 streetbikes, he stripped the engine and fitted a lightened, rebalanced stock crank with knife-edged webs polished to reduce oil drag.

This was the work of Falicon Engineering in Florida, a drag racing specialist V&M knew from their straight-line days, who also fitted their own trick oval-section chrome-moly steel conrods. “Steel rods are OK, because you’re not using too many revs, so you don’t need titanium,” said Steve, who retained the standard R1 forged pistons, with the valve pockets slightly relieved for added clearance.

“But with just a little help from Yamaha they eventually sourced a couple just eight weeks before the team’s debut race in Ireland at the North West 200 in May”…

Most work inevitably went into the cylinder-head, which Mellor ported, flowed and polished himself, raising compression to 13:1 and reshaping the valve seats. He retained the stock valves, rather than fitting special one-piece stainless steel ones, owing to lack of time, albeit with special springs to cope with a 1,000 rpm higher rev limit of 12,500 rpm, compared to the streetbike. “The five-valve head isn’t the easiest to get top end horsepower out of,” said Steve, “though it’s better with a 1,000cc engine than the 750, because there’s more room to get a better combustion chamber shape.” V&M’s own design of billet camshafts were fitted, with just 0.5mm more lift on the three 23mm inlet valves and 1mm more on the pair of 24.5mm exhausts, but a lot more duration as well as steeper ramps, to open and close the valves more quickly. The ram air induction missing from the original street R1 was adopted, using a large 15-litre QB Carbon airbox force fed through a central duct leading from under the nose of the carbon fibre replica fairing, over the top of the huge radiator made by F1 car specialists Docking at Silverstone, offering twice as much cooling area as the stock R1 rad, into the 100% sealed, pressurised airbox.

But before fitting the flatslide carbs he’d expected to use, Mellor decided to see how the stock 40mm BDSR Mikuni CVs worked in terms of power, knowing that these would make the bike more rideable – and when the V&M dyno showed 174 bhp at the back wheel at 11,750 rpm with these fitted, he knew he had what Rolls-Royce term ‘sufficient power for the job in hand’ – especially since that was a static dyno figure, with at least 5-10 bhp more to come at high speed due to the ram air effect. Interestingly, that same dyno had recorded an output of 132 bhp at 10,500 rpm for a stock R1 straight out of the crate – and 158 bhp for the HRC-built RC45 Honda engine the team had previously raced on behalf of Honda Britain since 1995, until falling out with Big H midway through the ‘98 season. “The V4 Honda engine suits the Isle of Man,” said Steve Mellor, “and you’re not going to beat it with a World Superbike-spec 750 in-line four – it’s too revvy, and it makes the wrong kind of power. But a bigger 1000cc motor – that’s different, though to be honest it surprised even me how good it was straight out of the box.”

“the V&M dyno showed 174 bhp at the back wheel at 11,750 rpm with these fitted, he knew he had what Rolls-Royce term ‘sufficient power for the job in hand’”…

Just how good that is was underlined by the christening of the David Jefferies bike in Ireland. At that stage, Iain Duffus was thought of as the team’s lead rider, so his bike was the one used for V&M’s R&D, leaving David Jefferies’ R1 racer to be finished off in the NW200 paddock without the engine even having been run on the dyno, due to shortage of time. With Tuesday night’s practice too wet to take part in, it was left to DJ to run the bike in on the street the next day, covering 50 miles in everyday traffic, fitted with street tyres and a trade plate.

It was left to DJ to run the bike in on the street the next day, covering 50 miles in everyday traffic, fitted with street tyres and a trade plate…

That got it ready for Thursday practice – in which he showed the worth of V&M’s preparation as well as the Yamaha R1 package by scorching the brand new bike to pole position ahead of the fleet of Hondas – and his own teammate! Come race day, the young Yorkshireman underlined his own worth by winning both races and setting a new outright lap record at 122.26 mph on a bike which hadn’t existed until five days earlier, clocking 189 mph through the speed traps on a motorcycle which Steve Mellor admitted was “not very aerodynamic” – especially with an, er, well-built rider like DJ aboard. Pretty impressive…

V&M retained the stock Yamaha CDI but used a remapped igniter box with a different curve and higher revlimiter, and fitted a special Akrapovič exhaust with no EXUP power valve and balanced headers, which Mellor modified to give 8 bhp more midrange power. According to him the stock gearbox ratios were perfect for road courses, but the clutch was beefed up to handle the extra power, with a billet aluminium basket to hold the standard plates. 88ft-lb/119Nm of torque was delivered at 9,500 rpm, compared to the streetbike’s 62ft-lb/84Nm at 6,200 revs – but, said Mellor, there was at least 75ft-lb/101Nm available on the racer all the way from 4,000 to 12,000 rpm, the main reason why V&M riders could shortshift everywhere, relying on the Yamaha engine’s bags of grunt to go places fast.

Unlike teams like Mihara Project which had already raced the then-new R1 in the Superbike class in Japan, V&M paid no attention to stiffening the Yamaha’s chassis, which was almost completely standard. Admittedly, this was originally due to lack of time before the NW200, but the bikes handled so well there, said Jack Valentine, that they remained in basically stock guise after that. Proof of how effective a package the street R1 inherently was came in the Senior TT, when Iain Duffus discovered on the startline that his steering damper had broken, leaving him to ride the whole six-lap race into second place behind his teammate without a damper, including breaking Carl Fogarty’s previous outright lap record for the bumpy, demanding TT Course on his final lap! Awesome.

So the stock twin-spar aluminium frame was completely unbraced, and the street swingarm also retained, but fitted with a Penske race shock such as V&M had used for many years, so knew well. Although the stock R1’s 41mm Showa upside-down fork deflected too much under heavy braking for short circuit use, it worked fine on road courses, said Valentine, though it was revalved to offer more adjustment, and fitted with stiffer springs. Plus, to increase stability while at the same time speeding up the steering, V&M dropped the fork 10mm in the triple-clamps for quicker steering, but reduced the fork offset from 35mm to 31mm via a set of ProMach adjustable yokes, in turn dialling up more trail.

Improved brake performance even over the R1’s benchmark Sumitomo street stoppers came via a set of PFM’s 320mm cast-iron discs, which used a single huge circlip to attach the floating discs to the carrier, and were gripped by the British company’s own six-piston calipers. Rear brake was an R6 disc with Brembo four-pot caliper – made necessary by the fact that Jefferies actually used the rear stopper very hard to slow down, a trait underlined by the two warped rear discs he managed to suffer from that year! Dymag wheels shod with Pirelli slicks completed the package, which weighed in at a creditable 167kg half-dry, with no titanium fasteners but an empty stock steel fuel tank which had been expanded in capacity from 18 litres to 22.5 litres, to enable the bike to run two laps of the TT Course between fuel stops – this was marginal, otherwise, with the standard R1 tank.

But perhaps the most impressive statistic about the stripped-out streetbike that became a TT titan, making a clean sweep of the world’s major road races in 1999 by winning the North West 200, both Formula 1 and Senior Isle of Man TT races, the Ulster GP, and Macau GP, was its price. According to Jack Valentine, the total cost of building each V&M R1 racer was the princely sum of £26,000 ($53,000 AUD) and change – and V&M were ready to duplicate the bike for any customer for that price, including a signed dyno chart attesting to the power your money had bought you. But wasn’t that what the Superbike class was always supposed to be all about, taking the best-selling sportbikes in the marketplace, tuning them up on an affordable basis, then going head-to-head on the racetrack to determine who’s best, in crowd-pleasing, spectacular style? Or would you prefer a vastly more costly MotoGP racer-with-lights, produced in very small numbers and thus available only to a lucky few? Answers on a postcard to Dorna in Barcelona, please….

Thirty grand Australian could buy customers a hot road going limited edition YZF-R1 from V&M back in 1999. Where are they now? Let us know if you have one…

V&M YAMAHA RF1-SP: King Of The Streets

In 2000 V&M proprietors Jack Valentine and Phil Mellor put the seal on their crushing clean sweep of road circuit results with their R1 racer by building a limited-edition customer street version of the Jefferies bike, which was sold through Yamaha UK dealers, or direct from V&M for customers outside Britain. For a cost of £14,500 ($30,000 AUD), including a one-year warranty, Stevie Streetracer could get his hands on a bike that threatened to go Hayabusa-hunting in a straight line – yet would comfortably out-handle Suzuki’s porky speed king in turns.

The V&M King of the Streets was also available in a maxed-out RF1-SP version costing £18,500 ($38,000 AUD), which was the closest thing possible to DJ’s racer fitted with lights, complete with all the fancy hardware that made the TT-winning bike the ultimate R1. Each of the fifty RF1s was individually numbered and personally autographed by David Jefferies on the nose of the carbon fairing, making them a valuable commodity today, as well as still heaps of fun to ride.

“It had a stock bottom end, pistons and conrods, but a ported, gas-flowed cylinder head fitted with V&M’s own performance camshafts”…

The base-model RF1 was tuned by V&M’s Steve Mellor to deliver 155 bhp at the rear wheel at 10,800 rpm, on the same dyno on which a stock R1 fresh out of the crate put out 133 bhp, and the team’s TT-winning race bikes produced 174 bhp. It had a stock bottom end, pistons and conrods, but a ported, gas-flowed cylinder head fitted with V&M’s own performance camshafts, the same ram-air induction system as the racer, including its large 15-litre QB Carbon pressurised airbox, with carburation on the standard 40mm Mikuni CVs modified to suit, but the stock exhaust headers, complete with EXUP system, fitted with a Vance & Hines titanium silencer. The ignition curve had also been reprogrammed.

Revalved stock forks, a fully adjustable Penske shock, stock frame and swingarm, LSL steering damper and rearsets…

Chassis-wise, much of Yamaha’s stock R1 kit was retained, just as on the racer, but with a fully-adjustable Penske race shock offering 25mm extra ride height at the rear, to make the bike steer a little quicker, while the 41mm upside-down Showa forks fitted to the stock R1 had been revalved and fitted with stiffer springs, while also dropped 10mm through the triple clamps to effectively reduce the head angle and sharpen the steering. A German-made LSL steering damper and rear sets, Goodridge braided steel brake lines (but still the standard R1 brakes), a rear seat cowl and special-edition paint job closely based on the Jefferies bike’s race livery, completed the base-level RF1 package.

But for an extra £4,000 in total, you could add the works and go for broke in terms of hardware and performance, with the RF1-SP. This had the same lightweight Dymag wheels as the R1 racer, shod with Pirelli Dragon Evo Corsa rubber and fitted with the same light but effective 320mm PFM cast-iron brakes as the Jefferies bike – three-piece stoppers with the narrow floating discs attached to the lightweight carriers with a single huge circlip, and gripped by the British company’s own six-piston calipers, with a Brembo master cylinder. Mind you, since the finished bike now weighed just 169kg half-dry complete with lights and a licence plate, there was that much less to stop.

And the stock fork was now clamped by the racer’s adjustable ProMach triple clamps which, as delivered by V&M, offered 4mm less offset than stock at 31mm rather than 35mm, in order to increase trail and provide extra stability, just as on the racebike. Engine-wise, the same level of tuning was maintained, but with an Akrapovič full-race exhaust system which did away with the EXUP and delivered an extra 5 bhp at the top end – making for an output of 160 bhp, only 14 bhp less than the racer, with 84ft-b/114Nm of torque at 8,600 rpm. Seriously pukka, and a true racer with lights.

And the stock fork was now clamped by the racer’s adjustable ProMach triple clamps which, as delivered by V&M, offered 4mm less offset than stock at 31mm rather than 35mm, in order to increase trail and provide extra stability, just as on the racebike. Engine-wise, the same level of tuning was maintained, but with an Akrapovič full-race exhaust system which did away with the EXUP and delivered an extra 5 bhp at the top end – making for an output of 160 bhp, only 14 bhp less than the racer, with 84ft-b/114Nm of torque at 8,600 rpm. Seriously pukka, and a true racer with lights.

1999 V&M Yamaha YZF-R1 Racer Specifications

Engine Liquid-cooled DOHC inline four-cylinder four-stroke, 20-valve, offset camchain, 74 x 58mm bore x stroke, 998cc, 13:1 compression ratio, 4 x 40mm Mikuni BDSR V&M carburettors, Yamaha CDI, V&M igniter box, six-speed gearbox, billet alloy clutch basket, wet multi-plate clutch, Akrapovic exhaust

Chassis Yamaha Deltabox frame, alloy twin-spar, extruded alloy swingarm with rising rate linkage, 41mm SHOWA inverted forks, Penske shock, 24º rake, 96mm trail, 1390mm wheelbase, 54/46% weight distribution, 2 x 320mm PFM cast iron rotors with six-piston PFM calipers (f), 220mm Yamaha rotor with Brembo four-piston caliper (r), Dymag 3.50 and 6.00in x 17in cast alloy wheels, 120/70 and 180/55 – 17in Pirelli slick tyres.

Performance Top speed 304km/h (North West 200 1999), 174RWHP@11,750rpm, 167kg wet.

Owner V&M Racing, Manchester, UK.