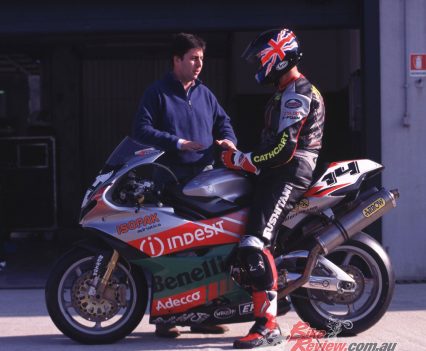

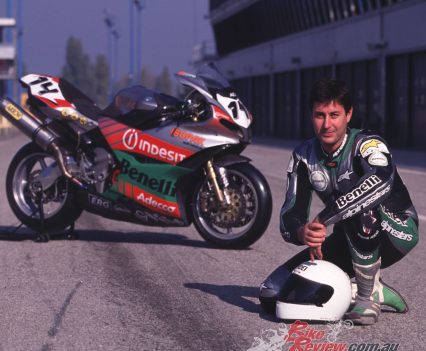

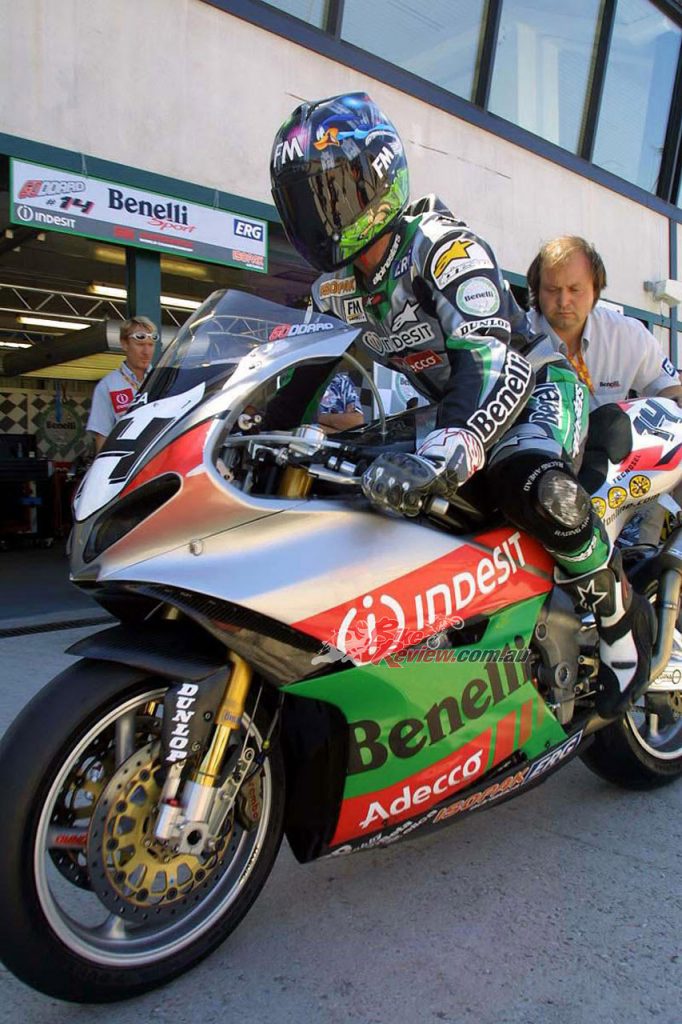

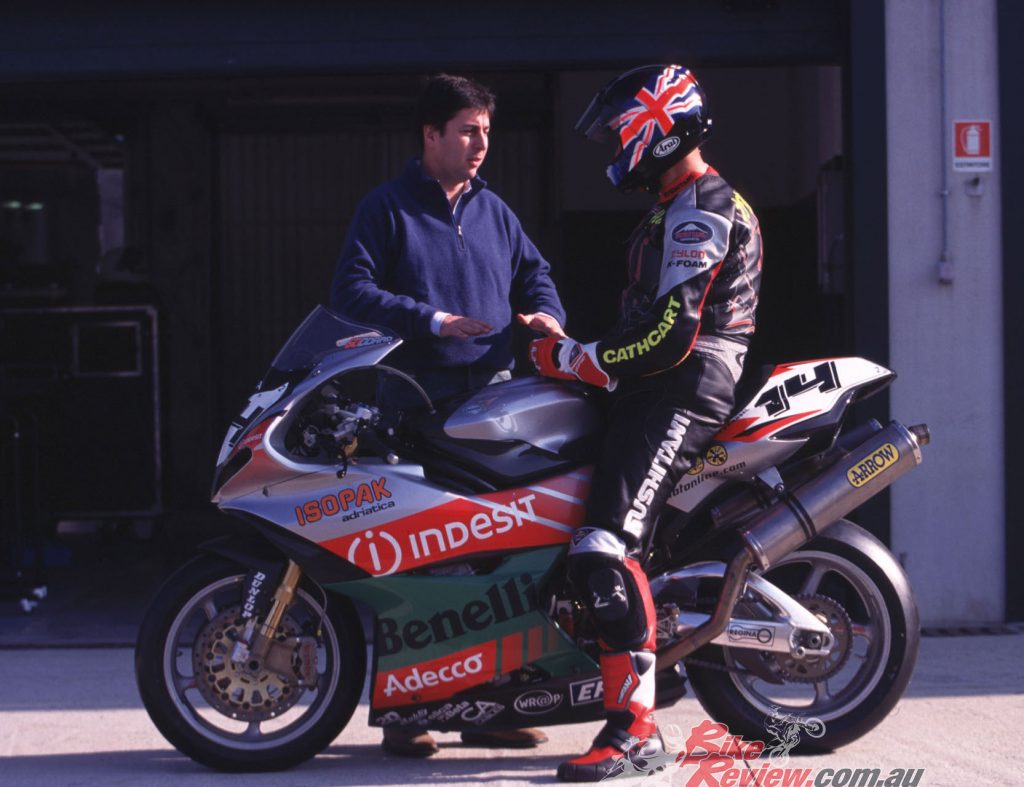

Exactly 20-years ago the late Andrea Merloni had Benelli back on the SBK grid with our very own Peter Goddard at the 'bars. The bike had potential but never got there. AC rode it at Misano that year... Test: Alan Cathcart Photography: Kel Edge

This Benelli was the first motorcycle to take advantage of WSBK’s three-cylinder 900cc capacity class, joined in 2003 by Foggy Petronas. In June 2001 the 60,000 fans lining Misano racetrack on Italy’s Adriatic Coast witnessed the debut of the Benelli Tornado.

The Benelli Tornado was one of the wildest and unique entires into the 2001 WSBK season, but it was short lived.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

It had been built just 20km down the coast at Pesaro. Sadly, Goddard DNF’d in both races there after qualifying 27th on the grid out of 34 starters, albeit just a tenth of a second behind Chambon’s factory Suzuki – but he made three excellent starts, each time passing 6-8 riders into the first turn. Two weeks later at Laguna Seca, another milestone in Benelli’s comeback trail was reached, with Goddard scoring Benelli’s debut WSBK point with 15th place in Race Two, after qualifying 21st – ahead of both semi-works NCR Ducatis. Then at the next round at Brands Hatch, Benelli began playing with the big boys, when Goddard won a no-holds battle with Okada’s factory Honda SP-2 to finish 13th.

Benelli lost momentum after that, though, with mechanical issues denying any points in the next two rounds, before the Tornado’s debut half-season of competition ended with another 13th place finish in the final round at Imola. This marked the absence of the bike’s creator Riccardo Rosa, who’d left Benelli to be replaced by former Bimota chief engineer and Aprilia R&D leader, Pierluigi Marconi, who today heads up the now Kawasaki-owned Bimota. But the Tornado 900 had now become a genuine points contender on the SBK grid, and in doing so confounded the critics who stamped the entire Benelli revival project as a rich man’s toy, of no substance.

VIDEO: BENELLI TORNADO SBK BEHIND THE SCENES

Goddard had started a total of 12 races that first half-year of WSBK competition, with those two 13th places at Brands Hatch and Imola being his best results. In 2002 the team raced only part of the season once more, again with a single bike, starting in just 17 of the 26 races, without the two-time WSBK race-winner, former Japanese 500GP and Australian Superbike champion ever quite managing to break into the top ten – 11th and 12th in the penultimate round at Assen were the best of his nine points-scoring finishes. At the end of the season Merloni withdrew Benelli from racing, in order to focus on getting the street version into production.

“Goddard had started a total of 12 races that first half-year of WSBK competition, with those two 13th places in Brands Hatch and Imola his best results”. At the end of the season Merloni withdrew Benelli from racing, in order to focus on getting the street version into production.

The Benelli Tornado 900’s distinctive exhaust note – revvier than a twin, deeper and more muscular-sounding than a four – was a sound that hadn’t been heard in world-class competition for 28 years. The last they were heard was on the MV Agusta triples which won 14 World titles between 1966 and 1973. The Tornado Superbike’s debut marked the return to racing after a comparable period of Italy’s historic Benelli marque, winner of two 250cc World Championships. It had last gridded for a World Championship event 28 years earlier, at the tragic Italian 250GP at Monza in May 1973 that cost the lives of Jarno Saarinen and Renzo Pasolini, both ironically former Benelli riders.

“We made a very careful analysis of the various options before committing to such a major investment,” said Andrea Merloni about the choice of a triple.

“For several reasons the triple stood out. You can make a small, compact engine with good aerodynamics, plus it sounds great – and nobody else makes one for Superbike racing, at least not yet! And Ing. Rosa convinced us that, compared to a 750 four or a 1000cc twin, the triple was also the most effective choice for World Superbike – the best of both worlds.”

The bike was developed with racing in mind. With the set back being that they had to make a road going homologation model in order to meet WSBK rules.

After its debut appearance in public at the 2000 Isle of Man TT, the prototype Tornado’s 898cc 12-valve three-cylinder engine with its one-piece cylinder block canted forward slightly at 15° from vertical, was revamped internally to deliver more power at higher revs. This resulted in even more radical ultra short-stroke dimensions of 88×49.2 mm, compared to the original version’s 85.3×52.4 mm format. The 120° crankshaft throw was retained, but instead of the big-bang TT bike, a 240° 1-3-2 firing order was adopted, with two-ring forged Asso pistons delivering 13:1 compression mounted on Pankl titanium conrods, and a gear-driven counterbalancer mounted at the front of the crankcase.

Valves were now larger, with dual springs on the twin 36mm inlets (up from 32mm) and 30mm exhausts (was 29mm) for each cylinder, set at a 28° included angle, but with a steep angle of downdraught, breathing from an 18-litre sealed carbon-fibre airbox (almost 50% bigger in capacity than on the IoM prototype) fed by the twin ‘nostril’ airducts which had been redesigned in shape, and increased in diameter. The Tornado Superbike racer was consequently 8mm wider than the initial prototype, thanks to the revised ducting and wider cylinder bores, though still only 23mm wider than Bayliss’s World champion Ducati 996R V-twin.

“Gear drive to the Tornado Superbike’s new-profile higher-lift twin overhead camshafts now replaced the street prototype’s chain-driven DOHC.”

A trio of 55mm Dell’Orto sandcast throttle bodies was fitted under SBK kit rules, to replace the diecast 53mm units which the street Tornado wore. Similarly, that streetbike used a British-made Sagem fuel injection ECU, but Goddard’s Superbike racer employed one produced by EFI in Bologna, founded by a team of ex-Marelli engineers. A single external top-spray injector – rather than the two either side of the butterfly on the Sagem EFI – was mounted above the throttle body intake trumpet for each cylinder, with the central one of these 20mm longer than the other two, to enhance midrange performance.

The maximum power in the form the Benelli debuted at Misano claiming 171hp@13,000rpm, with the revlimiter set at 13,200rpm. By contrast, Bayliss’s 2001 World title-winning Ducati produced a claimed 176hp@12,000rpm, with 181hp from Colin Edwards’ 2000 World champion Honda SP-1W, at the same revs – both figures at the crankshaft, whereas the Benelli’s was at the gearbox.

Maximum power in the form the Benelli debuted at Misano claiming 171hp@13,000rpm, an absolute rocketship.

The Benelli Superbike featured a side-loading, extractable, 6-speed cassette-type gearbox, which in combination with the dry slipper clutch allowed the team to change internal gear ratios in just 20 minutes, all without having to strip the engine or even remove it from the frame. The shifter mechanism was attached to the gear cluster, so it was very accessible. Even more unusual was the cooling system, which followed the Britten V-1000 and Saxon Triumph-3 layouts which Rosa volunteered had inspired his design, in featuring a rear-mounted radiator behind the engine, beneath the seat, with dedicated internal ducting to supply cool air to it from either side of the front wheel.

The prototype street Tornado’s pair of electric extraction fans to blow hot air out the back of the seat were missing from the racer, which however had a 20mm wider water radiator than originally, plus a separate oil radiator. The rear-mounted radiator allowed the engine to be placed further forward in the frame than would otherwise be the case, in turn loading up the front wheel weight-wise for added grip, as well as delivering a short 1395mm wheelbase. Weight distribution was 53/47% frontwards, but excess kilos were always the bike’s main handicap, despite the complete engine scaling just 68kg. The Benelli weighed 172kg half-dry, 10kg over the SBK minimum weight limit for all bikes.

The rear mounted radiator allowed for an almost even weight distribution on the racebike, creating a very well balanced and predictable set-up.

The Tornado’s chassis was a modular one, with twin tubular steel frame spars pegged and glued with aircraft epoxy into a cast-aluminium rear frame section, in which the aluminium swingarm pivoted. Because of the very compact engine, the 570mm long swingarm was the longest on any Superbike, even more so than the then-current Yamaha R7’s, but delivering the same advantages in terms of traction and grip as on the Yamaha factory Superbike. The head angle was adjustable over a two-degree range from 22.5-24.5° via eccentrics, and was usually run at 23.5° with 98mm of trail for the 43mm Ohlins TIN-covered inverted fork – while the swingarm pivot was also adjustable for height over a 4mm range.

VIDEO: BENELLI TORNADO 900 SBK WARM UP!

Öhlins suspension and Brembo radial brakes completed the list of top-level hardware fitted to a bike whose narrow motor delivered a build as slim as a V-twin’s, with your arms tucked in close to the sculptured green ‘fuel tank’, which was actually the airbox shroud – the real fuel tank was behind and beneath it, using the free space rearwards of the forward-mounted motor. Seat height was very high at 840mm to allow the rear suspension to work at its best, but on street Tornados this was quite a bit lower at 810mm, with less of the rider’s weight on the bars – and his forearms.

However, this wasn’t the problem that most concerned Peter Goddard, when he gesticulated urgently to Riccardo Rosa as he gridded up for Race One at Misano, after the sighting lap: “There’s a problem with the fork preload,” he shouted. “Relax, Peter,” said Rosa reassuringly. “There’s 24 litres of fuel in the bike, and it’s the first time you’ve ridden it with a full tank…!”

THE RIDE

My chance to be the first person outside the Benelli factory to ride the Tornado Superbike even with less fuel aboard came at the team’s sun-blessed local Misano test track, then still a counter-clockwise course in those pre-MotoGP days.

Alan was lucky to ride the WSBK bike and speak with its creator during such an important time for Benelli.

The first thing you noticed when you came to throw a leg over the Tornado was how high you needed to lift it – this was a bike with a seriously tall seat, even more so than a Ducati with its exhausts tucked under your bum. At first I thought this was all Peter Goddard’s fault, a setup choice representing the heritage of his days as a top 500GP privateer and former Japanese champion. But the culprit was the rear-mounted radiator, which even with its carefully-integrated ripple effect to give space for the rear wheel on full compression, took up a lot of space right under the seat – not to mention the twin extraction fans mounted on the street Tornado, but absent from the racer.

“The first thing you noticed when you came to throw a leg over the Tornado was how high you needed to lift it.”

However, once aboard you noticed how, strangely enough, you seemingly weren’t perched as much on top of the Benelli as you certainly were on a Desmoquattro 996 Ducati, and the triple didn’t feel any wider than any factory V-twin Superbike – in fact, it seemed smaller and less bulky than Troy Corser’s works Aprilia. Even with the quite adequate protection from the Benelli’s pointy-screen fairing down the Misano main straight. The airbox shroud, which only partly masqueraded as a fuel tank didn’t intrude, and it was easy to wrap your arms around it without feeling you were trying to hug an oak tree. The Tornado felt quite compact for a 900cc Superbike, and though there was the usual amount of weight on your forearms for a racer, it wasn’t excessive.

Riding something as unique and priceless as this bike would’ve been a scary feeling, but Alan couldn’t resist giving it a thrashing, but fuel mapping and other issues did make it less than ideal.

That impression of slimness was reinforced out on the racetrack, where the Benelli flicked into a turn very easily, and changed direction well – though it was a pity that oil spread from a blown racecar engine the day before meant I couldn’t use the full Misano GP circuit, so couldn’t try the Benelli out through the pair of chicanes on the longer track. I believe the bike’s tall stature would actually help it get through these pretty well. But the steering geometry of the Tornado’s composite chassis and the forward weight bias let you max out the excellent grip from the front 16.5-inch Dunlop, in turn letting you use heaps of turn speed to overcome the single biggest handicap of the Benelli engine, its lack of acceleration.

That’s not to say it was a slug out of turns, exactly – but after watching as the Benelli mechanics fire up the motor on the stand and noting the glorious-sounding engine’s high 3,500 rpm idle speed – surely chosen to try to counter any problems with the slipper clutch over race distance, for the same reason as Frankie Chili had his Alstare Suzuki running just as high on idle – I discovered on track that the Benelli had a downright peculiar power delivery. It pulled strongly initially from low down, say from 7,500 rpm onwards out of the tight final turn on the Misano short circuit – well enough to get a pretty impressive wheelie past the Pits if you short-shifted through the bottom three gears. But when the digital readout on the MoTeC dash showed anything much over 10,500 rpm, the engine seemed to slacken off, and stopped pulling so hard – as if it just fell off the torque curve, such as it was.

At first I thought this was a massive hole in the power band, but in my second, longer session I studied the effects closely, and didn’t think the power actually reduced, more that the three-cylinder engine simply stopped accelerating as hard as it had up till that point, as if there were a problem with the fuel mapping, the exhaust design or the cam profiles – or maybe all three! The result was the same – the engine just stopped building revs and seemingly went for a nap for 1,000 revs as you wound on the throttle in desperate search of more grunt to keep up with that privateer NCR Ducati in front of you, as Peter Goddard seemed to find himself doing in most races that season!

But then, just when you’d decided you better short-shift and access that meaty bottom-end power again, the triple motor would take off again, from just over 11,000rpm the short way to the seemingly rather low 12,600 rpm revlimiter imposed not only for my test, but also for Peter Goddard to race with – and it was a fierce-action, no-nonsense power switch, so you had to shift gear before you got there. Strangely, despite that, Pete didn’t use a shifter light to remind him when it was time to grab another gear. Benelli did have the wide-open KLS powershifter working well, though with an equally sensitive setting as on Foggy’s Ducati, I found myself quite often fluttering the engine as I moved from side to side about the Benelli, and grazed the one-up race-pattern lever with my boot.

The Benelli suffered from a lack of acceleration, so getting good cornering speed was a must for the triple cylinder.

Elsewhere, the Benelli gearbox felt good, with a crisp action that for a while I tried using a lot, in order to try to keep the revs up above the 10,500 rpm mark everywhere: pity it wouldn’t rev any higher, because for sure the engine was still pulling hard when it hit the revlimiter. But a 900cc three-cylinder four-stroke really doesn’t respond to being ridden like a 125GP bike, and on any circuit with a handful of tight turns, this would always pose a problem.

What I did appreciate, though, was the capability of the Benelli chassis to make light of my efforts to make the most of the flawed power delivery. I didn’t ride it for race distance, and maybe didn’t get as hard on the gas as Peter Goddard – but it seemed as if the Benelli came out of a turn pretty well. With that gruff-sounding engine initially driving well out of the Tramonto horseshoe second-gear left-hander at the end of the Misano back straight, before tailing off as the engine lost momentum. The high-up riding stance meant there was lots of weight transfer onto the back wheel when I opened the throttle, but the anti-squat setting on the Benelli’s Öhlins rear shock handled that well, and it steered brilliantly hard on the gas, with no power understeer that might push the front wheel.

While there were some quirks about the power delivery, the bike was very predictable, going where you pointed it.

The Benelli just went where you pointed it, and the same was true if you tried to keep up turn speed to maintain hard-won momentum, like in the banked Quercia third-gear right-hander opposite the Pits. The Benelli’s architecture meant you could trust that grippy front Dunlop to stick well thanks to the forward weight bias, and so the bike felt so planted I surprise myself how fast I could take the turn. Only downside was that, when you got back on the power again, it’d be just at the power threshold after the hiccup in delivery, so when you got a sudden rush of revs again, if you weren’t ready for it you’d get the rear 16.5-inch Dunlop spinning while still partly cranked over.

While I wouldn’t have cared to ride the Benelli on less forgiving Michelin tyres, on Dunlops you learnt to cope with the way the rear wheel spun up controllably under power if you crossed that threshold at the wrong moment – but much less pleasant was the snatchy pickup of the EFI/Dell’Orto fuel injection package from a closed throttle. Worthy of the originally similarly flawed R7 Yamaha, this had a really fierce, abrupt response when you got back on the gas again mid-turn, even with the high idle speed. This was probably a function of having a single external top-spray injector, rather than a differential operation with a second one south of the butterfly.

The way the bikes weight distribution was set-up was what made the bike much more predictable to ride.

The Tornado’s excellent chassis was stable around fast sweepers, like the Curvone left-hander onto the back straight – though here I found I sometimes needed to weight up the footrests to stop the handlebars flapping in my hands. That only happened if I tried going through there in fifth gear, still driving hard and thus loading up the rear tyre – but doing that gave me more revs at the end of the straight before braking for Tramonto than if I did it in sixth. The Benelli was adequately balanced under heavy braking from the radial calipers gripping the smaller 305mm Brembo discs Goddard opted for – perhaps one reason why the Tornado flicked into turns and from side to side so easily.

Slightly improbably, these smaller discs stopped the Benelli really well, aided by what extra help from engine braking still remained from the three pistons’ 12.8:1 compression via the setting of the slipper clutch. There was good stability as I downshifted through the gears, even if thanks to the frontal weight bias delivered by the forward engine location owing to having the radiator in the tail, I could repeatedly feel the rear wheel lifting beneath me when stopping hard. It never got out of hand, though.

Due to its extremely high compression, the engine braking assisted in bringing the Benelli to a reasonable speed into the corners combined with the small 305mm rotors.

More than a decade after De Tomaso had finally ceased production of motorcycles bearing the historic Benelli name, another of the lost legends of Italian motorcycling had joined its former racetrack rival, MV Agusta, in hitting the comeback trail – and moreover Benelli had beaten MV to the World Superbike grid. In creating the new Benelli Superbike, Andrea Merloni had also achieved a personal milestone, as he admitted to me at our test. “Everyone has a dream they long to make come true,” he said, “but only a few are fortunate enough to see it achieve reality. I’m one such person, who dreamed of bringing Benelli back to existence, with a model incorporating distinctive design, and leading edge engineering. Thanks to Riccardo Rosa and his team, the dream came true. Now our next step is to share it with our customers, alongside going after World Superbike success.”

The late Andrea Merloni on the Tornado Superbike at Misano in 2001. Injury ended his own superbike career…

ANDREA MERLONI THE SAVIOR OF BENELLI

Benelli’s resurgence under Chinese ownership – it’s Italy’s oldest surviving motorcycle brand, founded exactly 110 years ago in 1911, owned since 2005 by Chinese manufacturer Qianjiang/QJ – is essentially thanks to its former owner, the late Andrea Merloni…

The team at Benelli were more than happy to show off all their hard development work to the journalists.

Merloni sadly passed away on November 11th 2020, aged just 53. The multi-millionaire former Superbike and Motocross racer had died in his sleep in his Milan apartment, apparently from a heart attack, before his body was discovered by a maid the next morning.

Son of Vittorio Merloni, one of Italy’s wealthiest entrepreneurs who founded the Indesit domestic appliance empire during Italy’s post-WW2 boom, Andrea Merloni had the passion and drive, as well as Money. His plan was to raise Benelli from the dead in 1995, when he acquired the defunct Pesaro-based brand’s trademark from Giancarlo Selci. Merloni was intent on developing a brand-new line of Benelli models, and going racing with a range-topping sportbike. He completely relaunched the brand, and since the old Benelli motorcycle works in Pesaro had been demolished, Merloni constructed a brand new 7,000m² plant on the outskirts of the city which began producing Benelli scooters in 1997.

Pure Italian motorcycle heaven, as many of the now unobtainable Tornados sat waiting for their new owners.

But the Benelli badge also adorned an innovative new motorcycle, the Tornado 900 unveiled in July 1999 at a glitzy, high society presentation in Pesaro. The ultra-striking Tornado Superbike painted in Benelli’s traditional silver and green colours, with a radiator under the seat cooled by twin extractor fans in the tail, was powered by an all-new fuel-injected three-cylinder engine designed by Riccardo Rosa, the former Alfa Romeo and Ferrari F1 race engineer. Rosa headed up R&D for two years on the prototype MV Agusta F4’s radial-valve four-cylinder engine, before joining Benelli in January 1997. In the next four years after starting work on the Tornado 900 engine in July that year, Rosa and his 20-man development team produced one of the most innovative Superbikes.

The Tornado 900 featured radical styling by Italian-based British designer Adrian Morton, resulting in an alluring motorcycle which first ran in public in a special Isle of Man TT Parade in June 2000, ridden by Andrea Merloni himself. The following year, Merloni duly satisfied his passion for competition by joining the 2001 World Superbike series mid-season, with a tuned-up Tornado ridden by Aussie former World Endurance champion Peter Goddard. No matter that only a dozen complete Tornados existed at that point – the Flamminis who controlled WSBK back then were eager to grant a place on the grid for another brand, especially one as historic as Benelli.

The huge factory housed some of the best motorcycle engineering minds at the time, all with the plan to create something unique and amazing.

But the start of streetbike production lagged, and when customer Benelli Tornados eventually became available in 2002, they were far from trouble-free. After several attempts to resolve these problems, and the arrival of the acclaimed TnT 1130 Streetfighter version also designed by Morton, Benelli production ceased in June 2005. But in October that year the firm was sold by Merloni’s Fineldo holding company to Qianjiang/QJ for a €7 million purchase price, and the assumption of Benelli’s entire accumulated debt totalling €52.7 million. QJ in fact restarted production at Benelli’s factory in January 2006, having agreed to maintain the then 48-strong workforce in full.

A total of 1,947 Tornado 900s ended up being built in the model’s nine years of production.

After disposing of Benelli, Andrea Merloni later became President of Indesit, his ailing father’s choice to succeed him at the reins of the family empire. But, he was powerless to prevent a rival family faction headed by his twin brother Aristide from forcing through the sale of Indesit in 2014 against his wishes to American giant Whirlpool, for just over $1 billion. Not such a happy family – but a rich one…..

SPECIFICATIONS – 2001 Benelli Tornado WSBK

Engine: Watercooled DOHC 12-valve transverse in-line three-cylinder four-stroke with 120° crankshaft, offset gear camshaft drive and single gear-driven balance shaft, Bore and stroke: 88×49.2mm, Compression Ratio: 12.8:1, Displacement: 898cc, Fuel delivery: EFI with 3x55mm Dell’Orto throttle bodies, Gearbox: 6-speed cassette-type extractable with KLS powershifter, Clutch: Dry, multi-plate slipper clutch.

Chassis: Composite frame with twin tubular steel frame spars pegged and glued into aluminium steering head and swingarm pivot castings, Wheelbase: 1395mm, Head angle/trail: 24.5 degrees/98 mm, Front suspension: 43mm Öhlins fully adjustable inverted telescopic fork, Rear suspension: Fabricated/extruded aluminium swingarm with fully adjustable Öhlins shock and progressive rate link, Front brakes: 2 x 305mm Brembo steel discs with four-piston Brembo radially-mounted calipers, Rear brake: Single 220mm Brembo steel disc with two-piston Brembo caliper

Front wheel: 120/70R420 (16.5 in) Dunlop KR106 on 3.50in Marchesini cast magnesium wheel

Rear wheel: 195/55R420 (16.5 in) Dunlop KR133 on 6.00in Marchesini cast magnesium wheel

Performance: 171hp@13,000rpm, Dry weight: 172kg