In case you missed it! John Britten was the most unique motorcycle engineer to come out of NZ. AC rides his lesser known bike, the Aero-D-One... Photos: John Cosgrove/Don Tustin, with the help of Terry Stevenson.

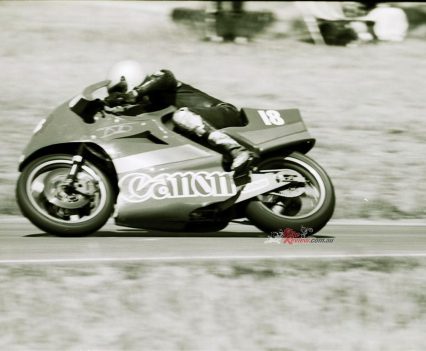

John Britten was best known for his V1000 creation, which to this day is still one of the wildest motorcycles to grace the international road racing stages. Proving he was far ahead of his time was the self-built Aero-D-One, sporting fairing that would almost be normal in MotoGP now…

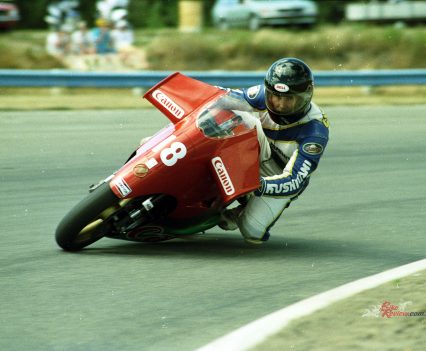

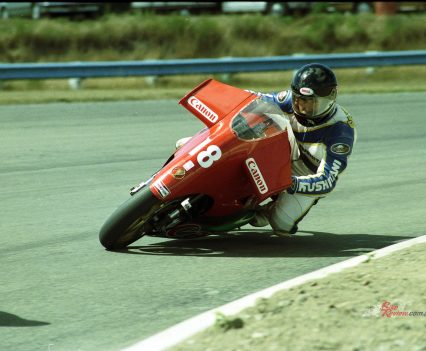

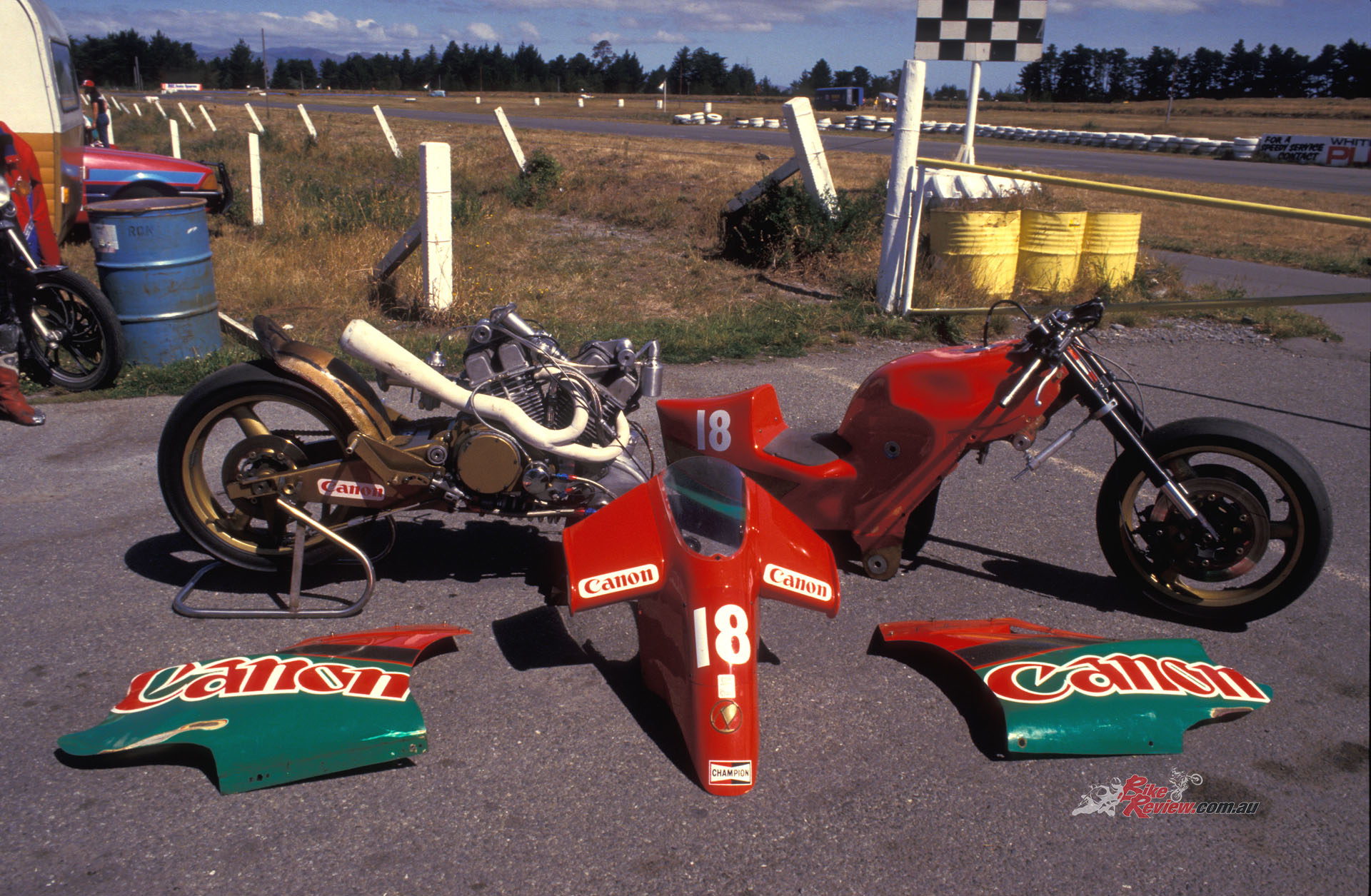

John Britten teamed up with Bob Denson to create one of the most interesting looking road-racers of the period. The Aero-D-One V1000… it was more widely known in NZ racing circles as the ‘Winged Wonder’.

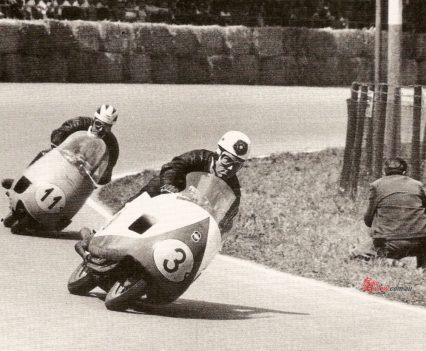

The current emphasis on aerodynamics in MotoGP and even in World Superbike, is a technology that’s been sitting around waiting to be revived for the past six decades. Ever since the FIM’s ban for the 1958 season of the so-called ‘dustbin’ fairings of the era, with their wind-cheating full-enclosure design aimed at maximizing top speed down the straights of the fast, open GP circuits of the day like Spa, Monza and the Isle of Man TT Course, motorcycle bodywork has remained stuck in a groove.

Check out our feature on John Britten here…

For sixty years the same essential format was followed, aimed at combining optimum straight-line performance with acceptable handling, while meeting the FIM’s requirement that the front wheel should be fully visible from the side, to avoid the problems with stability caused by side winds which the dustbin fairings created. But in just the past couple of years the factories in Europe and to a lesser extent Japan contesting top level road racing have begun to focus ever more on using aerodynamics to maximize tyre grip, as well as straight line performance.

But almost inevitably the late, great John Britten had already been there, done that, with his self-designed, self-constructed motorcycles which he built in New Zealand 35 years ago with the help of a bunch of dedicated mates, well before the advent of today’s wind tunnel-born aerodynamic GP racers. He did it first with a couple of bikes seeking to adapt Formula 1’s four-wheeled aerodynamics to a motorcycle application, and the second of these, the Aero-D-One aka ‘Winged Wonder’ was the first small step towards the makeup of the bikes filling MotoGP grids today.

Proving Britten was far ahead of his time is the Aero-D-One, with fairing that would almost be normal in MotoGP now…

I first met John Britten in December 1987 on a grass bank overlooking Manfeild [sic] race circuit in New Zealand’s North Island, during the European winter I spent racing in the NZ National BEARS Championship. We were both in our racing leathers, having strolled out from the paddock to watch practice and check on track conditions.

John had become one of New Zealand’s demon Vintage bike racers aboard a pre-WW2 Triumph Tiger he’d built and tuned himself – but his interests weren’t restricted to vintage bikes, and he was already collaborating with another local engineer as well as a coterie of friends in building a bike with aerofoil bodywork which tested John’s theories about two-wheeled downforce. These had been acquired during the building of his own 24-foot wingspan glider a decade previously – a design so efficient it needed only a 10mph wind to carry him aloft, and which worked so well that it once took off all by itself when not pegged down, while its creator was having a cup of tea!

Check out our other Throwback Thursday’s here…

The ambition to design, construct and actually race your own motorcycle from the ground up is held by many, but achieved by few. The fact that everything on all the Brittens starting in 1987 with the Denco-engined first Britten racer was made in New Zealand, apart from the wheels, tyres, suspension, brakes and gearbox only adds to our appreciation of John Britten’s feat in building them. One of Britten’s several helpers on the Denco-engined racing project was the chief engineer for Kenny Roberts’ factory Yamaha 500GP Lucky Strike team, Mike Sinclair, whom I knew well from covering and testing his team’s Grand Prix bikes. This gives you an idea of the calibre of people John’s enthusiasm attracted.

Allan Wylie sitting on the Britten Aero-D-One with Mike Sinclair, chief engineer for Kenny Roberts, sitting in the ute.

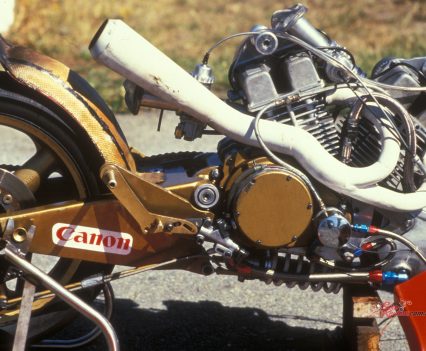

As a man constantly attuned to doing things differently by stepping outside the box in terms of motorcycle design, in 1985 John Britten had put into practice his esoteric ideas about chassis design and aerodynamics. First, a Ducati-based prototype named the Aero-D-Zero was built using the 900cc desmo V-twin engine of his mate Mike Brosnan’s Ducati Darmah, which permitted some successful experimentation, but it wasn’t till he hooked up with machinist Rob Selby and Bob Denson, boss of Denco Engineering in Britten’s home town of Christchurch, that the Aero-D-One V-twin racer project was born that same year.

Denco was a local manufacturer of hand-made 500cc Speedway engines, as well as a one-litre V-twin variant for use in the hair-raising world of Sidecar Speedway, obtained by mounting two of the solo singles at 60° to each other on a common crankcase. The fact that methanol was allowed in NZ road racing made the use of this engine to power John Britten’s project racer feasible, and in March 1987 he debuted the completed bike in the big BEARS meeting (standing for British, European, American Racers) at his local Ruapuna track outside Christchurch – having already dropped it on its side for the first time in trying to make a U-twin while testing it in the street outside his workshop in Christchurch!

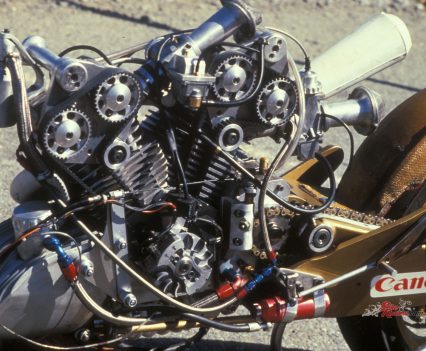

The Denco motor had genuinely awesome powers of acceleration and unlimited bottom end torque, but quickly ran out of breath when asked to rev – not surprising, really, given that Sidecar Speedway is mostly about who can outdrag the opposition to the first turn 40 metres away, and is then brave enough to shut the door on them, using the passenger as a sort of human fence. The engine’s 87 x 84mm dimensions and resultant cylinder-head design were fine for 600-metre cinder tracks, but not so good for the tarmac. Time for a rethink, spurred on by the help of Californian tuning wiz Jerry Branch, to whom John Britten sent a couple of the Denco heads for him to examine.

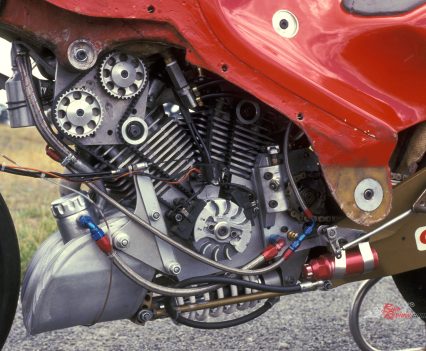

The fast but fragile Denco engine’s unreliability forced John to design and build his own engine, the first liquid-cooled 60° V-twin DOHC eight-valve Britten, which debuted at Daytona in 1989.

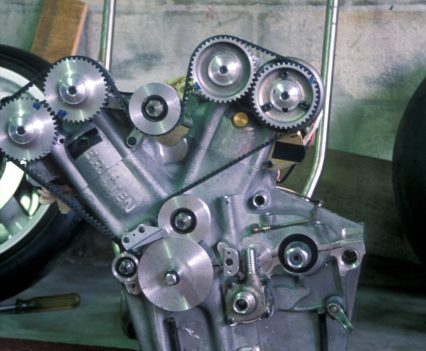

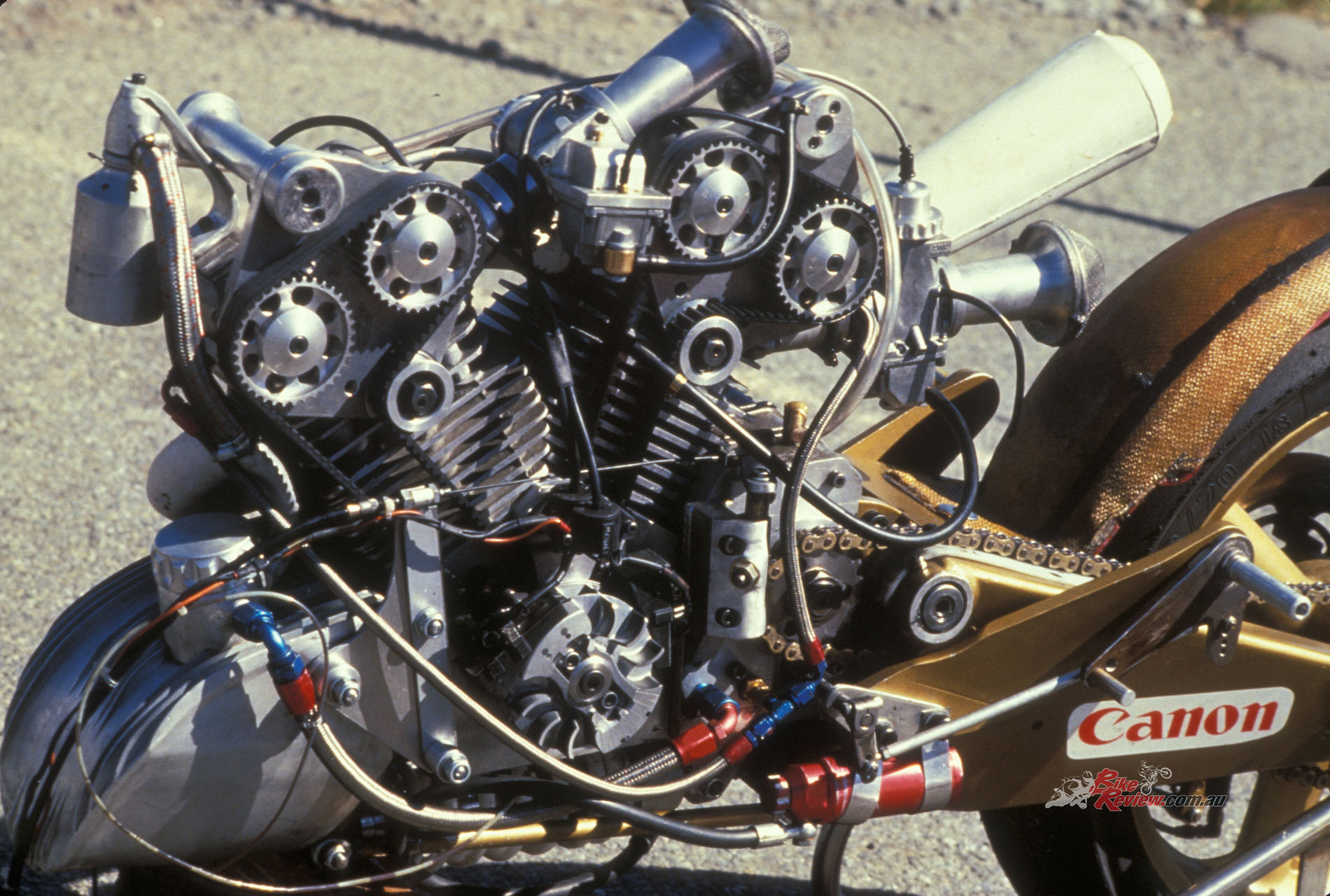

So during the Antipodean winter in mid-1987, the Denco engine was completely revamped into an ultra-short-stroke 999cc unit measuring 94 x 72mm. The four-valve cylinder-heads with belt-driven double overhead camshafts were re-ported and flowed by Jerry Branch, and fitted with larger austenitic steel valves to increase flow – 31mm inlets and 25mm exhausts, set at a flat-for-those-days included angle of 40° to each other. Likewise, the Denco cams were ground to Cosworth F1 profiles, and fitted with vernier adjustment to vary the valve timing.

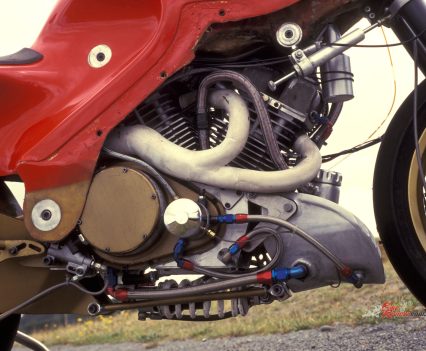

A 40mm Amal Mk.2 smoothbore carb was fitted to each cylinder, with a 2-into-l exhaust system and long open megaphone pointing at a hole in the back of the seat. Oil for the dry sump engine was carried in a beautifully-made alloy tank positioned in front of the narrow and therefore stiff crankcase, which was machined from solid rather than cast, as the cylinder-heads had been.

The use of the Speedway engine with total loss lubrication also dictated a revised oil system incorporating a return delivery, plus uprated oil feed to the crank. 120hp@9000 rpm at the rear wheel was claimed for the motor – potent for the time, when Marco Lucchinelli’s factory Ducati shortly to win the first-ever World Superbike round at Donington in April 1988, yielded 125hp. Running on a 13.5:1 compression and, of course, methanol – hence the minimal finning on the alloy cylinders – the whole engine scaled in at just 55kg, with ignition provided by a US-made Phelan flywheel magneto (originally designed for chain-saw use) mounted on the left end of the crankshaft, outboard of the bottom pulley for the twin cambelts.

The chassis consisted of a Kevlar/carbon-fibre monocoque, with the fuel contained therein via a F1 type rubber cell.

The chassis consisted of a Kevlar and carbon-fibre composite monocoque, with the fuel contained therein via a Formula 1 car-type rubber cell. “I got prompted to build a bike chassis from carbon/Kevlar composite after the success of the Kiwi boat KZ7 with a similar hull in the Perth America’s Cup challenge,” John Britten told me. “The two engineers involved with designing the NZ yacht took a hard look at my original drawings showing the detail of the layout and the moulding concept. They were very supportive, and confirmed that the structure stiffness would be three or four times greater than the same spar layout in one-inch diameter Reynolds 531 chrome-moly steel tube.”

The V-1000 Britten came close to achieving John’s ambition of defeating the Ducatis to win the Daytona BoTT/Battle of the Twins race, with Aussie Paul Lewis finishing second on his Britten to Doug Polen’s factory Ducati.

But without detracting from John Britten’s achievement, his motorcycle chassis concept was also strongly reminiscent of fellow NZ designer Steve Roberts’ successful 1983 Suzuki GS1000-powered ‘Plastic Fantastic’ TT Formula 1 fibreglass monocoque design, an NZ title-winning bike that was also raced by Dave Hiscock in Europe, before achieving great success in the hands of the late Robert Holden in NZ and Australia.

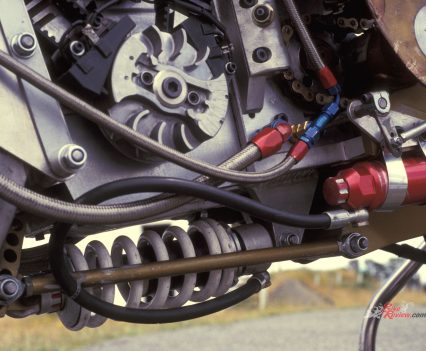

This had a similar rear suspension layout to the later Britten, with the WP monoshock located horizontally beneath the engine, and working in compression via a system of rods – a system also later copied by Erik Buell on his bikes. John Britten also received input from British immigrant Colin Lyster, whose fertile imagination had enlivened the ‘60s racing scene in Britain, where he’d designed his own Lynton parallel-twin 500GP racer, as well as a frame for Mike Hailwood to try to harness the fearsome performance of the works Honda RC181 500GP four-cylinder motor – and a Honda CB450-powered special complete with twin aerofoils.

The Aero-D-One monocoque frame consisted of 26 separate sections bonded together and weighing at 12kg in total, employing the engine as a semi-stressed member and attached to it via inserts, with pickups on each of the cylinder-heads, as well as on the swingarm pivot. This was incorporated in the rear of the gearbox casing, and was positioned as close to the drive sprocket as possible to give near-constant chain tension. Britten began construction of the monocoque chassis by hand-carving a master from a solid block of polystyrene, shaping it so as to be comfortable for himself as a rider.

Eventually he arrived at a form which enabled him to begin the moulding process, using a mixture of uni-directional carbon-fibre, Kevlar mat, high-density closed-cell foam, and his own preparation of vibration-resistant keying compound. The result incorporated internal ducting both to deliver cool air to the fully-enclosed engine – which was not liquid-cooled, remember – as well as to extract heat, while the curiously-shaped swingarm was a steel fabrication aimed at sacrificing weight-saving for stiffness.

Wheelbase was acceptably compact for a 1000cc V-twin at 1425mm, and the 25.5° head angle of the 54mm WP inverted fork could be varied by altering the rear ride height, ditto the trail by over a 24mm range either way thanks to eccentric bushes in the massive steering head. 18-inch cast alloy Marvic wheels and AP-Lockheed brakes were fitted front and rear.

Britten began construction of the monocoque chassis by hand-carving a master from a solid block of polystyrene, shaping it so as to be comfortable for himself as a rider. He fully encased the 1000cc v-twin in its fairing…

If all this wasn’t sufficiently innovative and wonderful, the weird part’s still to come – that Winged Wonder bodywork. “The winglets are my own solution to achieve a desirable increase in the frictional loading of the front tyre while cornering,” stated John Britten. “The principle relies on the fact that the efficiency of the inside wing is drastically reduced by the breakdown of lamina flow because of the near proximity of the rider’s body and shoulders to this wing. Conversely, the outer winglet’s efficiency is increased due to the absence of obstruction by the rider.”

“The winglets are my own solution to achieve a desirable increase in the frictional loading of the front tyre while cornering,” stated John Britten.

So, it was in theory like an upside-down aircraft wing, which became effective when the bike was banked over in a turn, with the rider hanging off in the opposite direction. OK – but what happens when you hit a spot of turbulence – like the slipstream of a rider in front of you, or worse still, a whole bunch of them? Well, that was the point of going racing, precisely to discover the bike’s response to such situations, and to develop a counter to them…..

That was the point of going racing, to discover the bike’s response to adverse situations, and to develop a counter.

Actually, the biggest problem I had when I first ventured aboard the Denco-Britten at Ruapuna in January 1988 during a practice day before the final round in the 1987-88 NZ National Championship series that weekend, was nothing to do with the bike’s specification as such. It was just that its creator wasn’t there, for the very good reason that it had spat him off earlier that week under braking at the end of the long drag-strip main straight, and then added injury to insult by jumping on top of him and playing skateboard for several dozen metres, by which time a good part of John Britten’s skin and even some bone had been worn away. But from his hospital bed, John dictated that the show must go on, which is how come Mike Sinclair and another of the Britten boys, the bearded Allan Brodie, turned up at Ruapuna with the rebuilt Denco-Britten in the back of a rather ancient, unrestored Model A Ford ute!

Having been moulded to suit the slightly shorter John Britten, the monocoque’s riding position felt a little cramped and awkward to me, though I expect it suited him just fine. The seat was quite high-set, forcing a fair bit of weight on to your arms and wrists, but the main problem was that it was hard to move around on the bike, as the designer intended you should if his theories about the winglets were to be justified. The cockpit felt strange, even at rest, with that tiny aero screen and the bat-like wings shrouding the handlebars, which on track gave a curiously remote feel to the steering, rather like riding a bike fitted with 1950s-style full-enclosure ‘dustbin’ streamlining.

“The cockpit felt strange with that tiny aero screen and the bat-like wings shrouding the handlebars, which on track gave a curiously remote feel to the steering, rather like riding a bike fitted with 1950s-style full-enclosure ‘dustbin’.”

Still, let’s forget about that for the time being, and concentrate on lighting ‘er up. Hook up the back wheel on the rollers, straddle the bike, listen for the valves to float on the Model A Ford ute’s motor as Sinclair floors the throttle – then dump the Denco motor’s clutch. Brrrrrrraaah! A glorious wall of sound enveloped the paddock as the V-twin engine burst into song – really, this was a great-sounding engine, and surprisingly smooth and vibration-free, too, especially for a 60° V-twin with no balance shaft or offset crankpins to smooth things out. It revved quickly and freely, but with a fair bit of flywheel effect, although torque was relatively slight and even without a tacho (which had been broken in John Britten’s crash), I could feel it liked plenty of revs, with a noticeable step in the power band from what I guessed would be around 6000rpm.

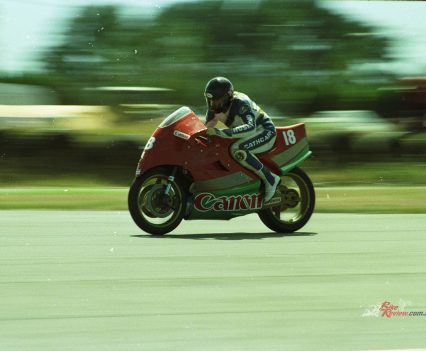

Out on the track, this showed up the flaws in the XJ900 Yamaha 5-speed gearbox’s spaced-out ratios, which were far from ideal for a peaky power delivery like the Denco’s. There was too big a gap especially between the very low bottom gear and second, giving you a choice in the Ruapuna infield between chattering the back wheel in bottom gear thanks to the high overall gearing needed for the long dragstrip straight, or lugging in second – which in turn meant slipping the clutch for decent drive out of the hairpin at the end of the straight. A six-speed gearbox would have been a big advantage with such a peaky engine, because it was only in the middle of the straight once the Denco had gathered up momentum and got going, that its real performance became apparent. It was F-A-S-T!!

“It had hardly any degree of sensitivity, making it difficult to accelerate cleanly and smoothly out of a tight infield turn.”

Thanks to the heavy springs needed to overcome the strong suction effect of that deep-breathing engine, the Amal carbs’ throttle was way too stiff and harsh, so it was not only difficult to work the twistgrip with any precision in slow corners, but this also made the bike quite tiring to ride, and meant blipping the throttle changing down under braking was very hard work. It had hardly any degree of sensitivity, making it difficult to accelerate cleanly and smoothly out of a tight infield turn. But the performance of the twincam eight-valve engine was truly impressive – I had a drag race down the straight with Robert Holden on the Honda Australia RS500 GP racer-beating ex-Kevin Magee 851cc Bob Brown Ducati I would later come to own and race, and the Britten just walked away from him – it was truly impressive, a very muscular motorcycle.

I couldn’t say the same about the Britten chassis, in the form I first rode it seemed to need a lot of development to get dialled in right. The main problem: it was physically gruelling to ride hard at anything like racing speed, with heavy steering thanks partly to the quite conservative geometry with that raked-out head angle. Yet, there was a real feeling of instability in turns, almost as if the chassis was flexing. The composite monocoque was an ultra-rigid structure, so no chance of it twisting or deforming, even if the fact that this first Britten was built in a modular fashion, with the forks attached to the monocoque, and the rear swingarm pivoting in the back of the gearbox, placed critical emphasis on the inherent strength of the three mounting points at which the engine was attached to the monocoque.

“In the form I first rode the Britten chassis, it seemed to need a lot of development to get dialled in right.”

John later discovered that his colleagues, unfamiliar with the bike’s settings in his enforced absence in hospital, had adjusted the rear suspension links incorrectly, raising the rear ride height so that the effective steering head angle was more like 22° than 25.5°, hence one reason for the sense of instability! But the problem was worsened by the soggy setup of the WP fork, which felt undersprung and overdamped, leading the Britten’s front Michelin slick to chatter badly at times in the infield. This showed up too under braking, especially at the end of the long main straight, where the highly effective AP-Lockheed brakes made the front end bounce up and down, the back end hopping in unison in the bottom two gears, thanks to the lack of a slipper clutch back in those far-off days to counter the heavy inertia of those big pistons under engine braking from high revs.

But what about the Winged Wonder’s aerofoils, you ask? Well – sorry, but I didn’t think they worked, or if they did indeed enhance front tyre grip by creating added downforce – and I have to say the Britten-Denco felt truly planted and ultra-stable in fast sweepers like the long final left-hand turn at Ruapuna – it was at the expense of practicality. I could feel the bike bobble around even more than usual when I came up behind another slower rider, and it was a definite handful to control the Britten in the stiff crosswind blowing across the straight at the time of my test. I could feel the wind getting under the upper winglet entering the straight, tipping the bike further over on its side which only added to the sense of physicality in having to wrestle it upwards again to stay on line, and avoid washing out the front wheel. Plus I had to lean the Britten sideways in a straight line to counter the wind, and avoid being blown off course. Not an easy bike to ride

“Still, after 20 laps of Ruapuna I thought I had the measure of the Winged Wonder, faults and all – and it was indeed extremely fast in a straight line, plus with a 1:1 kg/bhp power to weight ratio, it accelerated like a startled kiwi, too.”

After 20 laps of Ruapuna I thought I had the measure of the Winged Wonder, faults and all – and it was indeed extremely fast in a straight line, plus with a 1:1kg/bhp power to weight ratio, it accelerated like a startled kiwi, too. So when the engine of the Ducati broke later that practice day on which I was leading NZ’s hotly-contested 1987/88 BEARS National series, I jumped at John Britten’s generous offer from his hospital bed to try to clinch the title in the final round of the series by racing his Denco-powered device that weekend at Ruapuna. A fairytale result seemed on the cards when the motor’s 120hp took me from fourth to first place in one go down the main straight ending lap 1 – but when seemingly set for victory five laps from the flag, first became second, then second became third place, as the engine began intermittently cutting out on one cylinder. But so long as I finished ahead of the Bimota DB2 which was my closest championship rival, the NZ title would be mine – and he hadn’t passed me yet.

But you can maybe guess the rest: on the last corner of the final lap it cut out again while I was cranked hard over round the long, fast left-hand sweeper leading on to the Ruapuna finishing straight, just a few hundred metres from the chequered flag and that prized NZ title – but then it chimed in again hard while I was still leaned over, sending me climbing the staircase to highside heaven and off to hospital with a broken arm to join John Britten there! What might have been, if only….

John Britten had every right to be proud of his first 100 per cent New Zealand-built racer, which went a long way towards proving that Kiwis can indeed fly.

John Britten had every right to be proud of his first 100 per cent New Zealand-built racer, which went a long way towards proving that Kiwis can indeed fly – on two wheels, at least. Individual and innovative, fast but fragile, it was a fantastic feat to have created such an avant-garde bike entirely from his own resources – but at the time I couldn’t help but feel that he’d fallen into the classic trap of trying to do too much all at once. Time would prove that this was a challenge John was more than able to meet, in building the bike that even today, more than 30 years after it was created, is still widely acclaimed as one of the most ingenious, innovative and downright beautiful motorcycles ever made, the Britten V-1000. But that’s another story…….

1987 Britten-Denco Aero-D-One Specifications

ENGINE: Air-cooled 60° V-twin four-stroke with belt-driven DOHC and four valves per cylinder, 999cc, 13.5:1 Compression Ratio, 2 x 40mm Amal Mk. 2 smoothbore ,Phelan magneto Ignition, 94 x 72mm bore x stroke, 5-speed Yamaha close-ratio, Multiplate oil-bath clutch.

CHASSIS: Kevlar/carbon fibre monocoque, Front: Fully adjustable 54mm WP inverted telescopic fork Rear: Fabricated steel swingarm with fully adjustable WP monoshock Front: 1111/64-18 Michelin on 3.50 in. Marvic cast aluminium wheel Rear: 16/70-18 Michelin on 5.00 in. Marvic cast aluminium wheel, Front: 2 x 310mm AP-Lockheed discs with four-piston calipers Rear: 1 x 240mm AP-Lockheed disc with two-piston caliper

PERFORMANCE: 120hp@900 rpm (on methanol at wheel), 120kg dry, 265km/h top speed (Ruapuna 1988).

OWNER: John Britten, Christchurch, New Zealand.

1987 Britten-Denco Aero-D-One Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.