John Britten is the most famous name to come out of NZ in terms of two-wheels. A leader of innovation, AC gives us a rundown of his spectacular life... Pics: John Cosgrove/Don Tustin with help from Terry Stevenson

The words ‘genius’ and tragedy’ are often overstated, but it is beyond question that John Britten was an engineering genius, and that his death from skin cancer in September 1995, aged 45, was a tragedy of significant proportions for the world of motorcycling.

Proving Britten was far ahead of his time is the Aero-D-One, with fairing that would almost be normal in MotoGP now…

Check out our Britten Aero-D-One racer test here...

Though a crowded existence meant he had to combine two full-time careers as commercial property developer and hands-on two-wheeled visionary, with family life, John Britten’s achievements have received just acclaim the world over. The motorcycles he developed, by their technological excellence and avant-garde engineering, would have been sufficient by their very creation to ensure John’s name was remembered. The fact that they also won races around the world by defeating the products of established manufacturers with far greater resources, only adds to the calibre of his achievement.

The fact that the initially weird, later wonderful, Britten motorcycles were built and developed in Christchurch, New Zealand, which is the most faraway city on planet Earth from the mainstream of motorcycle evolution, only added to the mystique of John’s creations. But the extra dose of self-reliance that Kiwis get by being so remote from the two-wheeled world stage, added to John’s own spark of dedicated enthusiasm and innovative thought, resulted in a series of bikes that almost certainly could never have been built anywhere else.

The fact that Britten motorcycles were built and developed in Christchurch, New Zealand, which is the most faraway city on planet Earth from the mainstream of motorcycle evolution, only added to the mystique of John’s creations.

Yet John Britten was an unlikely candidate to display such technical expertise, for a reading disability bordering on dyslexia always made the acquisition of knowledge from books a laborious process. Perhaps that’s why he displayed such creative innovation throughout his life: John did what he thought was right and would work best, not what the books told him was correct.

Due to his reading disability bordering on dyslexia, John did what he thought was right and would work best, not what the books told him was correct.

So he developed an innovative method of working with avant-garde materials, like his wet-lay carbon fibre process; he used his own design of girder forks, not telescopics; he used the engine as a fully-stressed chassis member; he put the rear shock just behind the front wheel; he put the radiator under the seat; and he employed EFl when Bimota/Ducati’s Magneti Marelli fuel-injection was still in its infancy. John Britten was an innovator, and throughout the 10 years we knew each other, I stood with him many times as he examined another constructor’s handiwork.

John was obviously one of the early innovators of things like carbon-fibre and unconventional suspension setups.

The ones John admired most were those displaying similar mould-breaking design features. He had the eye of a critical observer, who at the same time was on a constant quest for knowledge to fuel his flow of radical ideas. Knowing him was a stimulating experience, talking to him about bikes or houses or flying or wine, or any of his other interests, was rewarding because of the way you were forced to re-examine your own accepted beliefs.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

The son of a bicycle shop owner who later became one of New Zealand’s leading property developers, John Britten’s first motorcycle was a derelict Indian he found dumped beside a country road. At the age of 14, he lugged it home on the train, and restored it to working order. After a bearded existence as a hippy drop-out in his early 20s, John bought a derelict stable in a suburb of Christchurch and started selling glass lamps and furniture he himself made there, while restoring the place as a dwelling.

John Britten teamed up with Bob Denson to create one of the most interesting looking road-racers of the period. The Aero-D-One V1000… it was more widely known in NZ racing circles as the Winged Wonder’

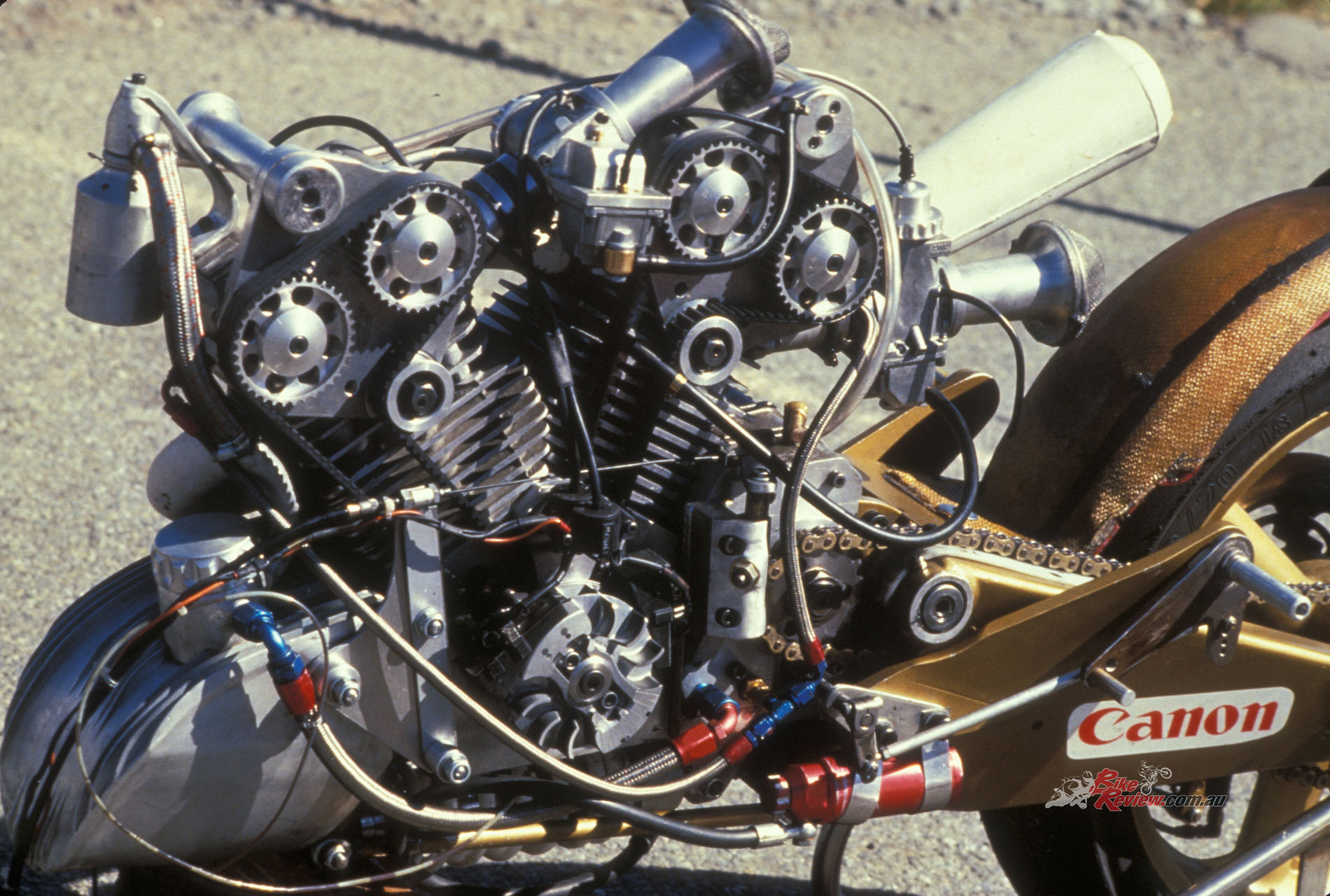

He later joined his father Bruce in his property company, while satisfying his love of motorcycles by building a Triumph Tiger vintage racer on which he became one of New Zealand’s most successful old-bike competitors. But John’s interests weren’t pigeonholed, and he teamed with a local engineer Bob Denson to produce a fearsome air-cooled 1000cc V-twin speedway engine used for Sidecar Speedway racing, which became the basis of the first carbon/Kevlar monocoque-framed Britten road racer, the Denco-powered Britten Aero-D-One. However, it was more widely known in NZ racing circles as the ‘Winged Wonder’, with its distinctive aerofoil bodywork which predated the modern generation of MotoGP and even Superbike racers bedecked with various aerodynamic embellishments.

The fast but fragile Denco engine’s unreliability forced John to design and build his own engine, the first liquid-cooled 60° V-twin DOHC eight-valve Britten, which debuted at Daytona in 1989.

The fast but fragile Denco engine’s unreliability forced John to design and build his own engine, the first liquid-cooled 60° V-twin DOHC eight-valve Britten, which debuted at Daytona in 1989. Its fully-stressed engine design allowed the chassis to be reduced to the minimum, with the full monocoque frame again made from carbon fibre, but still retaining conventional upside-down tele forks. The V-1000 Britten came close to achieving John’s ambition of defeating the Ducatis to win the Daytona BoTT/Battle of the Twins race, with Aussie Paul Lewis finishing second on his Britten to Doug Polen’s factory Ducati in the 1991 event.

The V-1000 Britten came close to achieving John’s ambition of defeating the Ducatis to win the Daytona BoTT/Battle of the Twins race, with Aussie Paul Lewis finishing second on his Britten to Doug Polen’s factory Ducati.

But Polen had made John angry by pulling wheelies en route to victory, so John went back to NZ determined to come up with a Ducati-beater, returning in ’92 with the definitive carbon-fibre girder-forked Britten motorcycle, whose distinctive blue and mauve livery underlined his talents as a stylist, as well as an engineer. A flat battery deprived Andrew Stroud of a seemingly sure win at Daytona with the new bike, but the Kiwi V-twin and its Kiwi rider scored the Britten’s first International race win at Assen later that year, before returning to Daytona in 1994 for a BoTT victory on the Florida Speedway.

The debut BEARS World Series in 1995 at last provided an arena for the Britten to demonstrate its excellence at World level, with Stroud a decisive champion after victories in Daytona, Thruxton, Zeltweg, Brands Hatch and Assen, with fellow-Kiwi Stephen Briggs on the second Britten runner-up in the series. It was a matter of satisfaction for all concerned, even including the Britten team’s rivals, that John Britten survived just long enough in the face of his dreadful illness to learn of his bike’s World Series success – a fitting memorial to one of the most innovative engineers and the nicest men that the world of motorcycles has ever produced.

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.