Marco Simoncelli was one of those riders you knew could've done more if he had the time, Alan took his famous championship winning RSA250 for a spin... Photos: Marco Morittu.

It hardly seems possible that it’s 10 years since super-talented Italian MotoGP ace Marco Simoncelli so sadly died aged just 24 in the Malaysian GP in Sepang on October 23, 2011. He was well known for winning the 250GP championship on this RSA250…

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

In his second season of MotoGP racing for the late Fausto Gresini’s Honda team, Marco had already secured his first pole position in Catalunya, his first podium finish at Brno, and just the previous weekend before his tragic loss had finished second in the Australian GP at Phillip Island. Clearly, this was a future World champion in the making in GP racing’s premier class. But Marco had already been there, done that in the hard-fought 250GP category, where in 2008 on his way up the ladder he’d emphatically won that category’s World Championship with six race victories and 12 podium finishes in the 16 races, to finish 37 points ahead of Spain’s Alvaro Bautista.

Marco with Gilera’s 1950s legend and six-time World champion (three times each with Norton and Gilera) Geoff Duke in March 2008 in an occasion celebrating Gilera’s centenary year that year. It was Geoff’s final public appearance before he passed away in 2015, aged 92.

The bouffant-haired bravado of the swashbuckling SuperSic in so convincingly winning the 2008 World title had made him a firm fan favourite, not just in his native Italy, and not only with a Grand Prix audience, either. For as convincing proof he was a racer’s racer, in between trying [unsuccessfully] to retain his 250GP World title in 2009, after no-scoring in the first two races after breaking his wrist in pre-season dirtbike training, Marco took on the challenge of a wildcard World Superbike ride at Imola aboard Aprilia’s new RSV4 on a spare weekend off in September that year. Finishing third there, after muscling his way past teammate Max Biaggi at the Pit Chicane on the final lap, confirmed him as perfectly at home on such bigger, heavier bikes.

Marco was a huge personality. Sure, his wild riding style wasn’t always to everyone’s liking, but his carefree demeanour and exuberant sense of humour, allied with his peerless riding skills and undoubted bravery, had gained him so many followers around the world – to which, after riding alongside him at a Mugello test day, I firmly added myself. For my own personal memories of this incredibly nice, lean and lanky guy with his huge mane of hair and phenomenal track skills came from getting to know him when I track tested his World champion Gilera RSA250, sharing the Mugello track and pit boxes with SuperSic as he commenced his four-stroke learning curve aboard the Aprilia RSV4 factory Superbike in preparation for racing it next weekend at Imola, a track he’d never previously ridden on, despite it being just up the road from his Cattolica home.

Alan was one of the very lucky people to take his bike for a spin and gain some coaching on how to get the most out of the tiny 250cc bike…

However, 2009 will also go down as the year which saw the demise of the 250cc class, one of motorcycle GP racing’s core categories. For reasons which are as much political as anything else, the Valencia GP that November saw the running of the last-ever quarter-litre GP race – and with it, the final nail in the coffin of what had consistently proved to be the most thrilling and most hotly, as well as most openly, contested class of road racing. As such, it had been a fruitful proving ground for successive generations of new talent, ever since the running of the first 250cc World Championship 61 years earlier, in 1949.

Before making the jump onto an Aprilia RSV4 in the premier class, Marco was one of the last ever 250cc GP winners…

Even if thanks to Marco’s early-season injuries it didn’t manage to stop Aoyama’s Honda winning the class’s last-ever World title in 2009, Aprilia dominated 250GP racing in its final years, winning 10 out of the 15 Riders’ titles and nine Manufacturers’ crowns ever since a certain Max Biaggi won the first of his four World titles in the category in 1994. That includes the single 250cc World crown won in 2008 for Gilera, Aprilia’s sister brand in the Piaggio Group, on the eve of its 100th birthday in 2009 by Marco Simoncelli aboard the badge-engineered RSA250 – for this was identical to the other factory Aprilias on the grid, save for the name on the tank and the tricolore bodywork of Gilera’s sponsor Metis, a leading Italian employment agency.

The chance to join Marco and the Aprilia factory race team at Mugello as he dialled himself in aboard the RSV4 in the run-up to Imola, not only gave me the chance to test the Aprilia Superbike myself – but also to bid a fond farewell to the 250GP class by riding his reigning World champion Gilera RSA250. OK, it was an Aprilia under the skin, but it said Gilera on the wrapper – and as such this ride represented a personal milestone for me, too. For back in 1989 I’d been the rider appointed with the task of bringing the Gilera factory back to road racing officially for the first time since 1964 and the final days of its World title-winning 500 fours, when Gilera’s newly-appointed Direttore Tecnico, Federico Martini, decided to develop a tuned Supermono road racer out of the DOHC single-cylinder Saturno 500 café racer which Gilera was then producing, mainly for the Japanese market.

I was entrusted with the task of racing it, and fortunately succeeded in taking it to victory in its debut race on home ground at Monza, just a long stone’s throw from Gilera’s historic Arcore factory where the bike was built. It’s now on display in the Gilera section of the Piaggio Museum at Pontedera – so the chance to ride its World champion 250GP two-stroke successor at Mugello in Gilera’s 100th birthday year, had added personal significance.

Usually when I rode a 250GP bike I had to take a deep breath to squeeze myself onto it, and get busy with a metaphorical hacksaw to prise my limbs aboard. That’s why I always enjoyed riding the lanky Valentino Rossi’s two-stroke racers as he made his way up GP racing’s capacity scale – and SuperSic had a lot of the Rossi in him, not only his flamboyant personality, exuberant riding style and evident versatility, but also the same tall build, all 1.83m of him. So his Gilera felt perfectly tailored to my 1.80m stature, meaning I could move easily about the bike in the Mugello chicanes, and tuck myself well away behind the pointy screen and curvaceous fairing to take full advantage of the aerodynamics down the kilometre-long front straight.

Throwing a leg over the Gilera, you’d expect it to be tiny due to its low capacity. Alan had no trouble at all getting comfortable on it at 180cm versus SuperSic’s 183cm.

Everything was just in its place and felt just right, reflecting the years of careful refinement and evolution which had honed the multi-World champion Aprilia/Gilera machine into such a perfect tool so single-mindedly tailored for success. The handlebars were quite low-set – presumably to help Marco tuck away down the straights, yet there was a good sense of leverage and control, even if your arms were wrapped tightly around the Gilera’s curvaceous fuel tank, and the footrests positioned quite far back, presumably to give more room for Marco’s long legs – and mine! Just as well, really: I needed all the help I could get on a comparatively small but perfectly-formed bike like this….

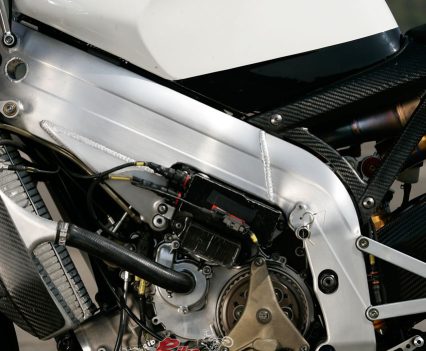

The analogue tacho and digital info display, same as on the RSV4 Superbike, comprised Aprilia’s traditional dash, back then the best and most instantly readable way of keeping on top of engine performance, while indicating just two pieces of extra data. One was the water temperature, held down to 55-60ºC on a warm 26ºC late summer day by the large carbon-shrouded radiator, and the other a simple ‘No.5’ reading, indicating the setting for the six-position traction control that Marco later told me he always used. “With setting six I spin the rear wheel sometimes, but with anything else it affects acceleration,” he said. “But this is a good system that really works – it made it easier for me to adjust to riding the Superbike!”

It had been six years since I’d last ridden an Aprilia 250, the 2003 RSW of that year’s World champion Manuel Poggiali – remember him? – and the biggest single surprise the SuperSic Gilera had in store for me was the significant extra torque and midrange performance extracted in the meantime from the twin-crank rotary-valve 90° V-twin motor by Gigi Dall’Igna – then Aprilia Corse’s technical guru, before his move to Ducati in 2014 – and his team of engineers at the company’s Noale R&D base.

“For the engine was a gem – purposeful yet forgiving in its power delivery, unbelievably eager-revving as well as finely honed.”

For the engine was a gem – purposeful yet forgiving in its power delivery, unbelievably eager-revving as well as finely honed. It carbureted well from low down, and transitioned well into the strong powerband, thanks to the dual-guillotine powervalve. It pulled well from 9,000rpm upwards, came on strong at 10,000 revs and held the power all the way to the 13,800rpm revlimiter, which thanks to the Gilera’s ride-by-wire throttle simply meant that the bike stopped accelerating – nothing as crude as an ignition or fuel cutout that might seize the engine on a two-stroke, just a giant electronic hand that reached out and told you that was IT in terms of engine speed.

This was some revs lower than where the Poggiali bike fell off the pipe at 14,500rpm six years earlier – but the extra torque Aprilia Corse engineers had uncovered in the meantime made it unnecessary to reduce crankshaft life by over-revving the engine, even to avoid a couple of time-wasting gearshifts between turns. You just geared the Gilera accordingly via the side-loading extractable cassette gearbox, so as to use that meaty midrange (well, by 250GP standards) from 9,000 revs upwards to surf that torque curve, and you’d go faster, with fewer revs.

Faultless, as well as fast – what a fantastic motor. Aprilia went the extra mile with a world class powerplant.

Acceleration was extremely impressive by 250-class standards, and this was the Gilera’s strong suit, rather than the extra top end power it certainly had also compared to its reed-valve rivals like Aoyama’s Honda and his previous KTM FRR250 ride I’d tested three years earlier – getting to your bike’s top speed quicker than your rivals is at least as important as being faster than them outright, once you’ve got there.

“Acceleration was extremely impressive by 250-class standards, and this was the Gilera’s strong suit, rather than the extra top end power it certainly had also compared to its reed-valve rivals like Aoyama’s Honda.”

A key ingredient in this was the way the Gilera engine picked up revs so fast in second, third and fourth gears on Marco’s Italian GP gearing I was running, working the wide-open race-pattern powershifter as soon as the green shifter lights across the top of the dash that started flashing from just 13,200 revs upwards, ended in a bigger, brighter red one at 13,400 – not much warning, but it was enough! There was quite a big gap to fifth, but then top was very close – typical fast-circuit two-stroke gearing to keep the show on the road, and the bike on the move up high.

“I like to keep the engine between 11,000 and 13,500, where there is best power and most acceleration,” said Marco, while trying to give an impression of a two-stroke teacher in pit lane. “But the engine is quite supple, I think. She pardons you if you make a mistake – and I make many!”

You could imagine the shock a non seasoned rider would get from pulling onto the straight and unleashing the power of a factory 250cc 2-stroke engine.

Not as many as me, mate, while trying to work out which gear to use where, and when, but eventually I got it right. I pulled 12,500rpm in top gear tucked in down the kilometre-long main straight – well, in my defence, I’m even more un-aerodynamic on such a little bike than Marco, who wasn’t even in the top ten for the published top speeds at Mugello that year, making him at least 9km/h slower than Bautista’s similar 292km/h Aprilia, and three k’s slower than his shorter, more streamlined teammate, Roberto Locatelli on the other Metis-sponsored Gilera.

“Marco blasted past me on the RSV4 Superbike at the end of the straight on his first flying lap on a Superbike!”

Force yourself to not even think about braking till the 150-metre board, then squeeze hard, hard, hard as you zip down through the gears in one go all the way to second gear, just before you tip into the San Donato curve and start climbing the hill out of there, noting as you do that you can powershift wide-open from first to second without any jerk from going through neutral, as on many other bikes. I had company there one lap, when Marco blasted past me on the RSV4 Superbike at the end of the straight on his first flying lap on a Superbike, only to out-brake himself and go way too deep into the turn, before squaring it off and cutting back in front of me.

“Those 250GP racers were the perfect track tool, with a level of performance j-u-s-t within the ability of an average rider to exploit to somewhere approaching its true potential”

No way I could emulate his late braking technique even when he got it right in subsequent laps, although I have to say the brilliant braking from the RSA250’s Brembo package, even with the smaller 255mm front discs, delivered so much confidence I ended up braking harder, later and deeper into turns each lap. Those 250GP racers were the perfect track tool, with a level of performance j-u-s-t within the ability of an average rider to exploit to somewhere approaching its true potential, which gave you so much fun trying to ride them hard.

It had been too long since I’d tested Poggiali’s Aprilia to make direct comparisons, but the revised RSA250 chassis package certainly seemed extremely agile in flicking from side to side in the four Mugello chicanes, yet was super stable powering round the fast fourth-gear sweepers at Savelli and Arabbiata. Above all it was predictable under braking and on turn-in and, even with my extra weight on board compared to Marco’s, didn’t push the front wheel unduly anywhere.

The RSA250 could certainly hold a line well, with exits being no issue once you got on the powerband.

The Gilera held a line well, even under acceleration from low down when with my extra kilos and the extra power compressing the rear Öhlins shock, I was frankly expecting it to understeer. Didn’t happen. It turned in well to the second-gear chicanes without any feeling of oversteer in putting the power on at the apex, and didn’t weave around when slowing hard thanks to those radial brakes, whose good bite allowed the use of smaller 255mm Brembo steel discs, which further reduced unsprung weight without sacrificing stopping power.

The Gilera had a 53/47 forward facing leaning bias. Meaning that when the rider was in place, it would balance to 50/50.

The Gilera felt pretty balanced, despite the 53/47per cent static frontal weight bias, so didn’t lift the back wheel more than just a couple of times at the end of the straight, thanks to its 50/50per cent weight balance with the rider in place – well, maybe more at the back to keep the wheel down, with yours truly aboard! Again, it felt forgiving – but this time, not just the power delivery but as far as the carefully-evolved chassis design is concerned, too.

Check out Jeff’s test of the Eugene Laverty RSW250 here…

The Öhlins suspension delivered so much feedback, coupled with the trustworthy, grippy Dunlop tyres, that you felt you could trust the Gilera’s track manners implicitly, and just focus on reducing your lap times. Despite its class-leading engine performance, it was a bike you felt secure enough aboard to start pushing your own personal boundaries with, knowing that the Gilera would allow you to deliver whatever you asked of yourself. That’s a perfect ride….

Indeed, this went to the heart of the appeal of any 250GP racer, why it was so seductively enticing to ride hard and fast in something approaching anger. Once you surpassed the threshold of at least reasonable racetrack experience and two-stroke technique, bikes like this were the ones that made you feel master of the universe. It was fast enough to thrill without being frightening, it handled and steered on autopilot, and it changed direction without requiring muscle or might, just skill and timing to do it just right. The more time I spent on the Gilera, the more addictive and engrossing it became, as I gradually polishing my technique, cleaned up my lines, worked on my braking markers, and took best advantage of that fabulous Aprilia Corse traction control to work on opening the light-action throttle sooner and harder exiting every turn, each lap.

“It was fast enough to thrill without being frightening, it handled and steered on autopilot, and it changed direction without requiring muscle or might, just skill and timing to do it just right.”

That’s because YOU feel completely in charge of bikes like the Gilera, not it of you, as is frankly the case even for experienced riders on bigger, more powerful MotoGP metal – and what’s more, the fabled connection between right hand and rear wheel was always present, and all correct. Provided you were careful to keep the engine running in the optimum power band and work the gearbox accordingly, I was as if you were at one with the bike – not sitting on it, but a part of it. Apart from an equally intuitive but slower Supermono four-stroke single, I know of no other motorcycle for average-sized riders as completely involving as a 250GP racer, and that certainly doesn’t apply to the much heavier Moto2 bikes which replaced it.

“I feel sad to have said farewell to motorcycle road racing’s most enjoyable, most fun and, yes, most enthralling kind of bike from a rider’s standpoint.”

I feel sad to have said farewell to motorcycle road racing’s most enjoyable, most fun and, yes, most enthralling kind of bike from a rider’s standpoint – but honoured and privileged to have paid GP racing’s quarter-litre class a fond farewell by riding the Simoncelli RSA250 Gilera in the company’s centenary year. If SuperSic hadn’t started the season with a broken wrist, for sure he’d have made it two in a row!

Very few people get a chance to throw a leg over a 250cc GP bike. Marco’s was Alan’s last ever time riding one…

But as I rode down the Mugello pit straight and into the Gilera pit box, I realised this was the end of an era – the last time I’d ever ride a current 250GP two-stroke. The bike I’d just spent 17 laps of Mugello aboard was history on wheels – pass a Kleenex, Marco.

TECH TALK – GILERA RSA250 WINNER

Up until the demise of the category in 2009, the 250GP Aprilia two-stroke had been a work in progress ever since 1989 – the year when what was then the small but ambitious family-owned Italian company jettisoned the customer tandem-twin Rotax engines which had earned it a debut 250GP victory at Misano in 1987 in the hands of Loris Reggiani, in favour of their own rotary-valve 90° V-twin motor, which went on to power a succession of World title-winning bikes. In the 20 years since then, the Aprilia Corse team of engineers and backroom staff, which at one time numbered as many as 89 people headed until his 2005 retirement by Dutch engineer Jan Witteveen, was responsible for Aprilia and its satellite Gilera and Derbi marques winning no less than 35 Riders and Manufacturers World titles in the 125cc and 250cc classes up to the end of 2008, as the direct European equivalent of Honda’s HRC.

Ing. Gigi Dall’Igna was the mastermind behind Aprilia’s GP success after he took over Witteveen’s position.

Ing. Gigi Dall’Igna was the man who succeeded Witteveen as Aprilia Corse’s Direttore Tecnico, having in any case been the R&D team’s main hands-on engineer in the years preceding his rise to the top job. With the demise of the company’s troublesome RS Cube MotoGP triple at the end of 2004, the enormous costs of which had contributed greatly to bringing Aprilia to its knees financially, leading to Piaggio acquiring it that same year, Dall’Igna was able to focus all the company’s attention on 250/125GP success, and the result was four years of Aprilia dominance in each category from 2006 onwards. However, as he revealed to me after my ride on the reigning World champion Gilera RSA250, development of the company’s two-stroke racebikes had been at a standstill since mid-2007, except as a vehicle for developing electronic systems for the RSV4 Superbike, which began to take firm shape just as it became clear than Dorna and the FIM had jointly decided to kill off the 250GP class.

“We produced the RSA250 mainly to resolve some handling issues we had with the previous RSW,” said Dall’Igna. “It was more a question of architecture than performance – we redesigned the engine in order to locate it differently in the frame, and repositioned the gearbox, all to try to improve the chassis setting. Bautista and Luthi raced with it first at Brno midway through the 2007 season, and it was a good improvement – Bautista won at Estoril on it after only two races. All five full factory-supported riders had this bike for 2008, but after that we stopped development on the 250, and just refined what was already a good package – so Simoncelli’s bike is mechanically unchanged from last year when he won the World title.”

After Piaggio decided to focus on WSBK rather than MotoGP, with the RSV4 project, the RSA250 acquired a different imperative, as an electronic testbed for the forthcoming Superbike.

“The RSV4 was still too green to perform this role, so we used the 250 as a dynamic prototype, especially to develop a traction control programme,” says Dall’Igna. “We’ve employed traction control on the RSA250 since the third race of 2008, and after three or four races we had it working very well. Then in September 2008 we transferred the entire package to the RSV4, and began adjusting it to the slightly different demands of the V4 four-stroke engine. We saved time and learnt a lot doing it this way, and it definitely improved performance of the 250, too, although it’s important to underline I didn’t force any rider to use it – they were free to choose, and at least one preferred not to do so. But one reason Simoncelli adapted so quickly to the Superbike was because he was already used to this!”

Aprilia’s traction control system, which was entirely developed in-house, had six different degrees of intervention, varying from Level Six (hardly any control) to Level One (lots of it), between which the rider could swap instantly via a switch on the left clipon, with the resultant setting shown on the digital dash. At each track the Aprilia Corse electronics engineer could fine-tune the system by modifying the parameters corner by corner via the GPS system incorporated in it. But were the TC requirements for a two-stroke engine the same as for a four-stroke?

“The way in which the control is delivered is exactly the same,” declared Dall’Igna, “but it’s much more difficult to achieve this on a two-stroke, because the most important element in doing so is altering the ignition advance. Since on a two-stroke the exhaust pipe is critical to the performance of the engine, and altering the ignition timing is a way of heating and cooling the pipe in order to optimise horsepower, and performance, the fact you must do this for another reason, to control grip at the rear tyre, makes mapping all this very difficult.

Check out our test of the WSBK Aprilia RSV4 here…

A four-stroke engine like the RSV4 runs around 40º of ignition advance most of the time, so it’s easy to vary the timing for traction control purposes. But on a two-stroke which goes from 30º at low revs to about 4º at peak rpm, if you alter the timing half a degree from 30º it doesn’t affect engine performance much – but do the same at 4º, and it’s a big difference! You’ll certainly lose performance, and it may even detonate, and hole a piston.”

So, very precise electronic control of the ignition timing and TC mapping is crucial on a two-stroke – although with the demise of the 250GP class, such skills were inevitably liable to be less sought after…

The 54 x 54.5 mm 90º V-twin Aprilia rotary-valve engine with twin contrarotating cranks in Simoncelli’s Gilera RSA250 delivered 107 bhp at the gearbox, at 13,750rpm. Thanks to the crank layout and the 90º angle of the special RSA cylinders, which had different stud spacing than on the customer RSW250LE engines, hence weren’t interchangeable, there was no need for a counterbalancer to eliminate vibration as there was on the 125GP single.

“The powervalve slides operated sequentially, in order to deliver two separate pulse waves to the exhaust gasses, with the lower one opening first at around 9,000rpm, followed by the upper one around 2,000 revs later!”

Each cylinder carried an electronic powervalve which contained sequentially-operated dual guillotine slides controlled via the firm’s own Aprilia Corse management system, whose ECU integrated with the dash incorporated various electronic engine management programmes controlling data recording, the ride-by-wire digital throttle, ignition timing, powershifter and powerjet, as well as traction control. The powervalve slides operated sequentially, in order to deliver two separate pulse waves to the exhaust gasses, with the lower one opening first at around 9,000rpm, followed by the upper one around 2,000 revs later. The result was more torque, and a fatter midrange, said Dall’Igna.

The Gilera’s carbon fibre fuel tank contained a fuel pump feeding 4per cent/25:1 mixture from it to the pair of 42mm Dell’Orto flatslide powerjet carbs housed in the complex carbon fibre moulding comprising the airbox on the right side of the engine, and the pump was also used to maintain a high ambient pressure inside the airbox, with the aim of improving the incoming charge. Surprisingly, Aprilia used the same design of exhaust pipe for every circuit: “We keep the exhaust constant, then work on different cylinder porting and ignition timing, and other items,” said Dall’Igna. “This reduces the variables, so we can concentrate on improvements.”

The cylinders had five transfer ports and three exhausts, with twin booster ports and carbon fibre rotary valves fed by the twin Dell’Orto carbs – and Dall’Igna insisted that, unlike Honda and Cagiva, Aprilia was never tempted to experiment with fuel injection on its two-strokes. “But I believe a KERS regenerative brake system could have been a big advantage for the two-stroke engine,” he says. “I asked the FIM in 2005 if we were free to use this, but they said the MSMA must decide, and then they told us it’s too costly and heavy, without ever really making any proper assessment – probably Honda didn’t like the idea, because they could see how it would benefit their hated two-strokes!”

For sure it would have been a big advantage, because of course with no engine braking you must use the brakes very hard, and this produces a lot of kinetic energy which you can use to tune the engine quite differently to produce more bottom end power. Doing so would remove top end performance, but you’d compensate for that with the KERS – and the advantage this would bring would more than make up for the extra weight of the KERS box. KTM actually built a bike that used it, and then were prevented from racing with it because they were told it was against the rules. Well, it wasn’t – and it would have given our two-stroke engines even more performance.”

The RSA250 aluminium twin-spar chassis incorporated a carbon fibre subframe comprising the seat, and delivered an extreme front end weight bias of 55/45per cent on a bike which weighed bang on the class 100kg minimum, thanks to all the carbon-fibre – although with the lanky and relatively heavy Simoncelli in place, distribution was a more rational 50/50. Steering geometry saw the adjustable head angle set at 23°, with 100mm of trail for the 43mm upside-down Öhlins forks, while the beautifully-fabricated aluminium swingarm with a progressive link for the Öhlins rear shock, delivered a wheelbase of 1350mm on SuperSic’s bike, which was a little longer than the other RSA Aprilias, because of his stature! The whole bike was enveloped in Aprilia’s voluptuous wind-tunnel developed bodywork.

2009 Marco Simoncelli Aprilia/Gilera RSA250 Specifications

ENGINE: Watercooled 90° V-twin rotary-valve two-stroke with twin contrarotating crankshafts, and twin electronic powervalves, each with sequentially-operated dual guillotine slides, 249cc, 2 x 42mm Dell’Orto powerjet flatslide, Aprilia Racing digital CDI, 54 x 54.5mm bore x stroke, 6-speed side-loading extractable cassette gearbox, Multiplate dry clutch

CHASSIS: Carpental aluminium twinspar with carbon-fibre seat subframe, Front: 43mm TIN-coated Öhlins TTX20 inverted telescopic forks, Rear: Fabricated aluminium swingarm with single Öhlins shock and progressive rate link, 23.5 degrees/105-108mm rake/trail front wheel: Front: 120/80-17 Dunlop KR106 on 3.75in. Marchesini forged magnesium wheel, 165/55-17 Dunlop KR108 on 5.25in. Marchesini forged magnesium wheel, Front: 2 x 255mm Brembo steel discs with four-piston Brembo Monoblock radially-mounted calipers, 1 x 190mm Brembo steel disc with two-piston Brembo caliper

PERFORMANCE: 107bhp@13,750rpm (at gearbox), 100kg with oil and water, no fuel, 53/47 per cent static (50/50 per cent with rider), 285 km/h (Mugello – Italian GP 2009)

OWNER: Aprilia Motor SpA, Noale (VE), Italy

2009 Marco Simoncelli Aprilia/Gilera RSA250 Gallery