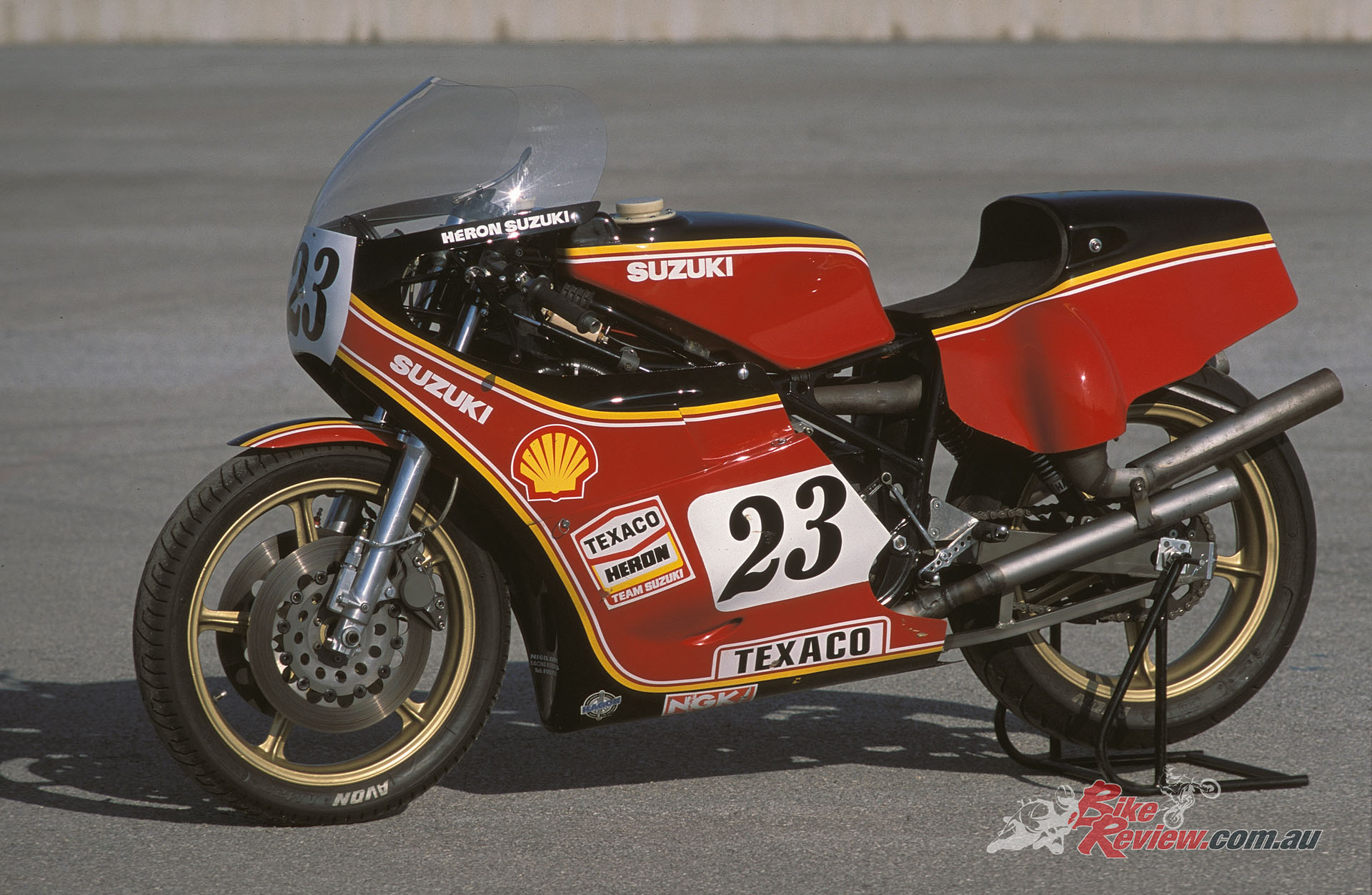

Cathcart walks us through the absolutely insane Suzuki RG650 XR23B GP Racer! Getting a chance to ride it and receive some tips from the late Barry Sheene. Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura

Loosely referred to as the RG650, Suzuki’s steroid-laden XR23B was originally conceived in 1976 as a testbed to advance development of the Japanese company’s XR14 500GP contender – the bike that had allowed Barry Sheene to earn Suzuki its first 500cc GP victory.

“The ‘flying commode’. The ‘pregnant duck’. The ‘trussed turkey’. The ‘plumber’s nightmare’. These are just some of the uncomplimentary nicknames bestowed on Suzuki’s 652cc XR23B.”

That win at the 1975 Dutch TT was the start of Suzuki’s mid-‘70s GP domination, with Sheene the first man to win the 500cc World title for the Japanese marque in 1976, retaining it in 1977.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

The ‘flying commode’. The ‘pregnant duck’. The ‘trussed turkey’. The ‘plumber’s nightmare’. These are just some of the uncomplimentary nicknames bestowed on Suzuki’s 652cc XR23B, the cubed-up rotary-valve square-four which the Japanese factory’s chief designer Makoto Hase concocted for the 1977 season, later on with its distinctive fat exhausts wrapped round the twin-shock rear end.

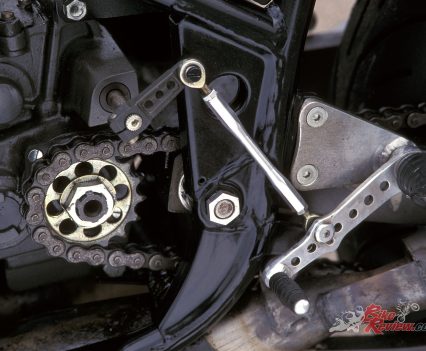

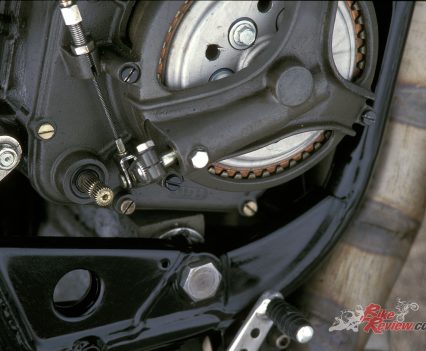

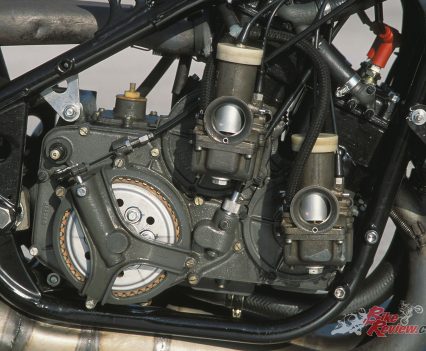

Barry’s first title was earned on a bike with the classic ‘level’ cylinder configuration for its RG500 square-four rotary-valve engine. But, that year, Hase and his Suzuki R&D team developed a larger 652cc version of the motor, featuring overbored stepped cylinders and a cassette-type extractable gearbox – both avant-garde race features.

Read what Barry Sheene, Randy Mamola and Steve Parish though of the beast here…

The extra capacity initially delivered too much power for the flimsy chassis and skinny rear tyres of the period to handle – so it was detuned to a less extreme 135hp@10,800rpm, still the first bike ever to deliver the coveted 1:1hp/kg. power-to-weight ratio which made it much more powerful than any other racebike of the day, and a lot more than the 114hp XR14.

The XR23B quite literally had “too much power”, the bike was detuned so the frame and suspension could keep up.

Hase-san had a good reason for the new engine layout, though: “We went to the stepped cylinder design because it lowers the centre of gravity and moves it forward,” he said. “Additionally, it is good for cooling because it frees the area just behind the radiator – if the front cylinders are high, there is less room for airflow. We can also extract the transmission from the right side, without the need to remove the engine from the frame.” This proved a great asset, allowing Suzuki race mechanics to swap gearbox ratios in under 20 minutes.

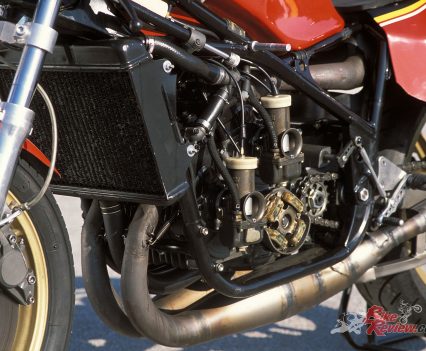

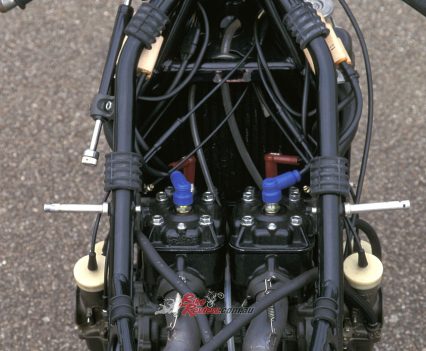

The liquid-cooled 62 x 54mm XR23 engine also differed from its previous 500cc counterpart in having just two crankshafts, one for each pair of cylinders, rather than four separate ones as on the RG500, each driving a primary gear beneath them, as before. Two 36mm magnesium Mikuni carburettors were mounted on each side of the engine, to feed the rotary valves splined to each end of the cranks, with the seven-port cylinders responsible for the harsh crack to the Suzuki’s engine note in those stinger exhaust days. Ignition was via a Nippondenso CDI, with the cassette-type six-speed gearbox mated to a multiplate dry clutch.

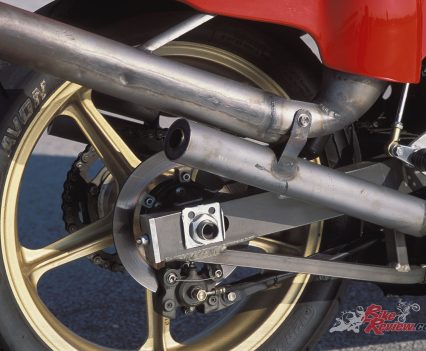

This ultra-powerful engine was however installed in an only slightly beefed-up version of Suzuki’s rather flimsy-looking twin-shock tubular steel frame as used on the RG500, fitted with bracing struts for the front cylinder-head mounts and 37mm Kayaba air-damped telescopic forks, set at a rangy 27.5-degree angle. Rear suspension came from two costly nitrogen-charged ‘Golden Shocks’ – expensive, because their aluminium bodies were handmade from solid billet, then sprayed gold!

Rear shocks made out of billet and being fully adjustable?! Nitrogen filled forks with an anti-dive system?! An insane setup for 1976…

These had no springs, and for the first time introduced the complexities of modern suspension setup in being fully adjustable for compression and rebound damping as well as, via the chosen gas pressure, for preload. The same pair of 295mm floating steel discs with twin-piston Tokico calipers as on the RG500 were mounted up front, with a single 240mm ventilated rear, providing stopping power that was barely adequate in view of the XR23’s astounding performance, in becoming the first modern racer to break the 300km/h mark, when trapped at 303km/h at Fuji Speedway in testing.

Suzuki’s view of the XR23 was as a rolling testbed for its 500GP programme, so they didn’t homologate it for World Championship Formula 750 racing, which at the very least would have required a spurious attempt to construct 25 street versions, as Yamaha had pretended to do (but never in fact did) in order to make the TZ700/750 eligible. Instead, four bikes were built and hastily air-freighted to Britain just five days before the April 1977 Transatlantic Match Races – one each for Texaco Heron teamsters Barry Sheene and Steve Parrish (riding for the British squad), plus a spare for Bazza, and a fourth bike for American Pat Hennen.

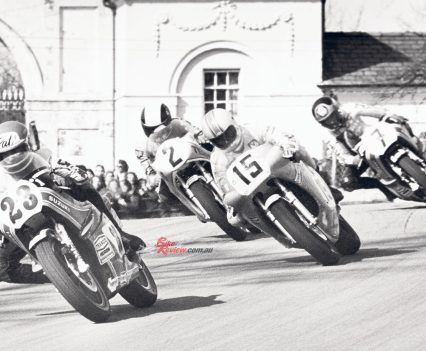

Pat Hennen leading Barry Sheene at Brands Hatch in 1977, both on Suzuki XR23s! Check out the MotoGP style wings!

Hennen is now established in the Suzuki works team run by British importers Heron for the factory, and first US rider to make his mark in 500cc GP racing, even before Kenny Roberts. Although it was Sheene who gave the XR23 its debut race win in one of the Oulton Park Match Race legs that Easter, Hennen finished top scorer for the series in which the American team scored an upset overall victory.

Check out our Two-stroke Tuesday on Sheene’s RG500 here…

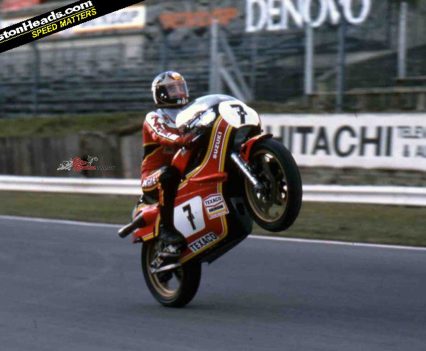

Suzuki then left the four 652cc bikes in Britain for them to race in the 1977 Superbike series, and were rewarded with the series title for Sheene with four race wins, and two more for Hennen en route to third place in the points table. It was a satisfactory debut season for Suzuki’s project bike, which led to the 1978 debut of the factory’s all-new XR22 500cc contender, which adopted the same stepped cylinder format and cassette gearbox that had by now been tried and tested successfully in the 652cc racer. But it came without the ten-pound iron bar that Barry had fitted to his bike, to keep the front wheel more or less in contact with terra firma when exiting turns!

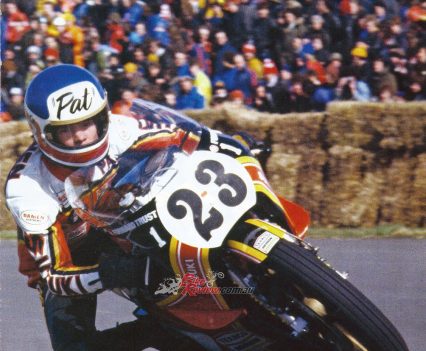

Also for 1978, Suzuki produced an uprated maxi-racer, the XR23A, with then-experimental chrome-bore Nikasil cylinders. Top speed at Fuji was now 309km/h, though power was the same and dry weight unchanged at 136kg, while the chassis and suspension were identical to before, but with slightly bigger 300mm front brakes. Again, the bikes were raced mainly in the UK, with Hennen once again finishing top overall points scorer in the Transatlantic Match Races, winning three of the six Easter weekend races, and Sheene one.

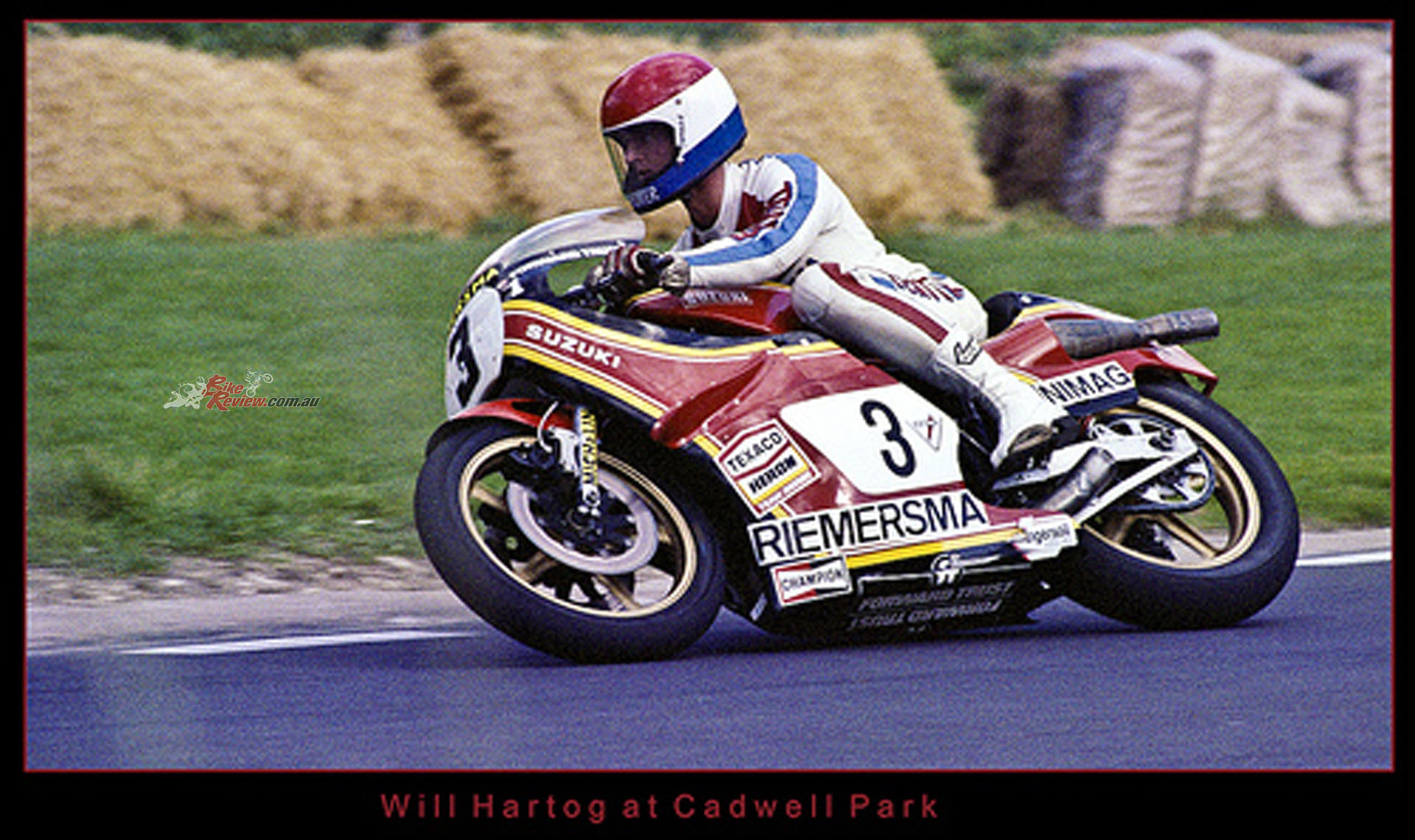

Hennen’s enforced retirement meant that there was a spare XR23A available, and this was entrusted to Dutch white knight Wil Hartog for the rest of 1978…

Pat had apparently learnt the setup tricks of the Golden Shocks better than Barry, one reason for his success alongside his equal mastery of the wheelstanding rodeo racer’s rush of power. But it was Sheene who retained his MCN Superbike series crown with six race victories, after the American sadly suffered his horrific career-ending injuries in the Isle of Man TT that year, soon after first defeating his illustrious British XR23A team-mate in the opening round at Brands Hatch.

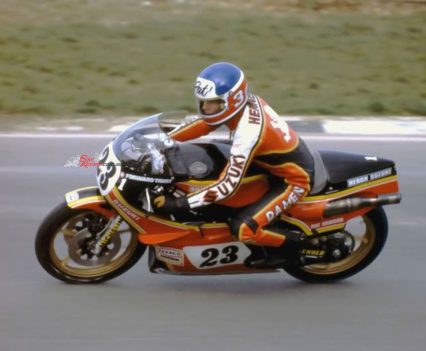

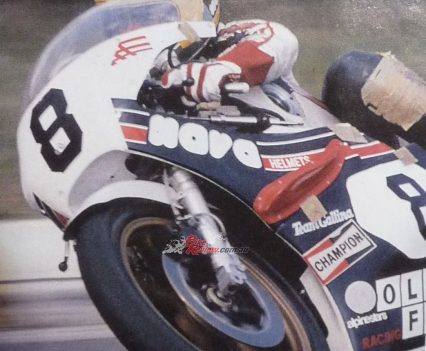

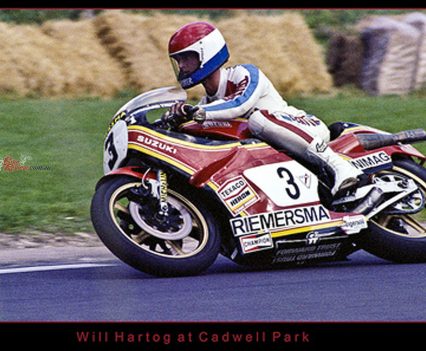

Hennen’s enforced retirement meant that there was a spare XR23A available, and this was entrusted to Dutch white knight Wil Hartog for the rest of 1978, culminating in his beating Barry to win the final round of the MCN Superbike series at Brands. After this, Hartog was given the bike painted in his trademark Riemersma colours for the whole of the 1979 season, with Tom Herron joining Sheene and Parrish in the Texaco Heron team racing in the UK, while a fifth bike was confided to Roberto Gallina’s Olio Fiat NAVA team to race out of Italy.

This machine, like the others, was fitted with a new exhaust system incorporating longer silencers as required to meet the new, lower 105dB FIM noise limits introduced that year – which presented Suzuki’s engineers with the problem of how to fit these without their extending back beyond the rear tyre, illegal under FIM rules. Solution: curve the expansion chambers for the rear cylinders initially up, then downwards around the twin rear shocks, and finally out and back.

The ugly-looking but effective result produced 3bhp more via revised porting of the Nikasil cylinders, so power was now up to 138bhp, still at 10,800rpm, with the brake package needed to cope with the XR23B’s explosive performance now also fitted, comprising 310mm twin floating front discs and a single ventilated 220mm rear.

In this guise the XR23B initially provided Barry Sheene with a platform to continue his dominance of the previous year, winning the first three races of the Transatlantic Trophy before suffering engine problems.

In this guise the XR23B initially provided Barry Sheene with a platform to continue his dominance of the previous year, winning the first three races of the Transatlantic Trophy before suffering engine problems in the final two rounds which contributed to another upset American team victory. But thanks to now focusing on regaining his 500GP world title from Kenny Roberts and Yamaha, the only round of the 1979 MCN Superbike series which Barry contested was at Scarborough, where he won both races.

But Steve Parrish did a few more and managed fifth place in the series, after being involved with teammate Herron in the tragic crash at the North West 200 which cost the life of the well-loved Ulsterman. But in general, the advent of the four-stroke TT Formula 1 category had removed the UK emphasis on the 750cc class, and the jumbo-Suzuki saw little action in Britain. Indeed, the FIM had announced that this would be the final year for the F750 World Championship – while paradoxically at the same time removing the reason for its decline by finally abandoning the homologation rules which only Yamaha had pretended to seek to find a way around.

This allowed the XR23B Suzuki to finally compete at World level, and its title-winning potential seemed assured after Virginio Ferrari took the Gallina bike to victory in the first F750 World series round at Mugello in April, following up a week later with a runaway win at Paul Ricard in the Moto Journal 200. But the Suzuki factory was more concerned with regaining its prized 500cc World crown than, as they saw, it, cherry-picking a defunct World Championship of second division status, hence declined to support Gallina’s assault on the series, which thus petered out.

Hartog’s third place finish on the Rimersma bike at the Assen round was the XR23B’s final appearance on the international rostrum, and apart from a solitary race in the hands of Randy Mamola at the Brands Transatlantic round in 1980, that was the end of the jumbo-Suzuki project, leastways at world level. Could’ve been a world champion? Very possibly so – but it certainly allowed Barry Sheene and, before his sad accident, Pat Hennen, to make their mark and win a lot of races against slower, less powerful opposition. Mission accomplished, within Suzuki’s narrow frame of reference for the project as a whole…..

After the 1979 season, the ex-Hennen bike was returned to the UK by Hartog, then shipped to the Malaysian Suzuki importer Guang Hoe where it was raced for a couple of years before being acquired by peripatetic German privateer, Gerhard Vogt. I remember racing against him on it in the 1982 Macau GP, though the only time my works Ducati V-twin was able to keep him in sight was round the twisty town part of the Guia public roads circuit – come the long straights along the coast, Gerhard’s two-stroke rocketship gave even Wayne Gardner’s works Honda Britain RS1000 the hurry-up.

After that, the XR23B eventually found its way back to Britain, where it stayed unused in a private collection until it was acquired in August 1999 by British enthusiast Chris Wilson, whose superb array of works two-stroke racers is a testament to the hitherto unconsidered GP heritage of the ‘70s and ‘80s post-Classic era.

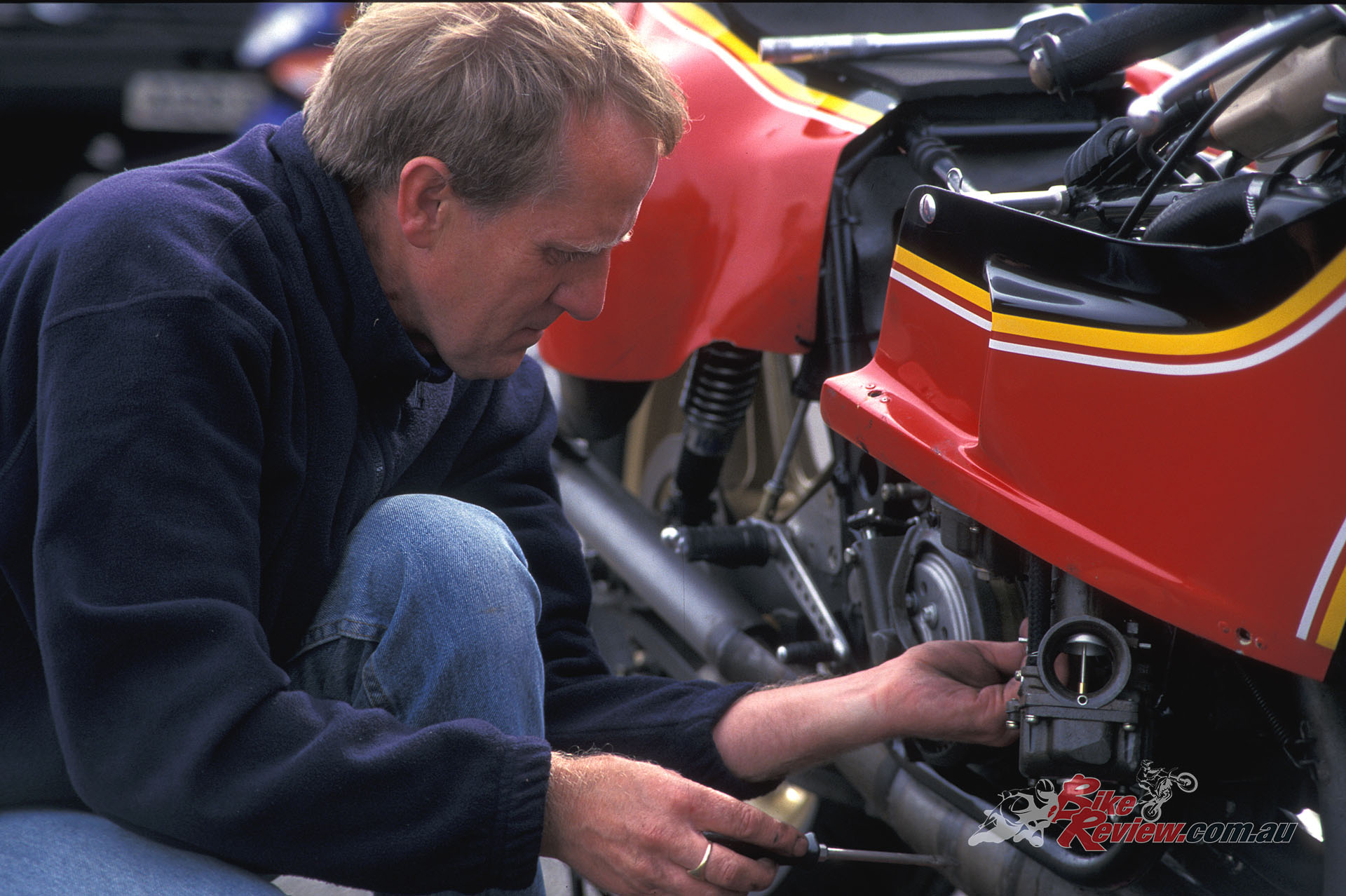

The man who looks after the Wilson collection of bikes and keeps them in authentic, trackworthy condition is Nigel Everett, whose Racing Restorations company did just that to the XR23B.

The man who looks after the Wilson collection of bikes and keeps them in authentic, trackworthy condition is Nigel Everett, whose Racing Restorations company did just that to the XR23B, in which form I was deputed to run it in for Chris at the Coupes Moto Légende meeting at Montlhéry, before my ‘teammate’ Barry Sheene swapped his Assen GP-winning XR14 RG500 for it, which back then was also in the Wilson stable. Later on, Chris and Nigel brought it to Snetterton for me to ride in something approaching anger – only for it to run a crank after just half a dozen laps.

AC at the Coupes Moto Légende meeting at Montlhéry. The XR23B was originally believe to be a Sheene bike, but the records show it was a Hennen machine.

At that stage, Chris Wilson believed it to be one of the Sheene bikes, hence the no.7 race number it bore back then – but Everett later acquired the prized Heron Suzuki race records courtesy of ex-team manager, the late Rex White, and further research revealed that this was Pat Hennen’s 1978 XR23A, updated to ‘B’ spec motor-wise for Hartog in 1979. Suitably rebuilt by Racing Restorations, and now bearing Pat’s no.23 race number, it was a case of third time lucky at a sunny Misano, a track better suited to such a long-legged bike, even if it was still overgeared on the shortest ratios in the spares box, so I could only grab a true fifth gear down the main straight in either of my two 20-minute sessions on the Suzuki. Still – plenty fast enough for me!

Riding The XR23B

I once shared the track with Barry Sheene on his XR23B, at an open practice session on the Brands Hatch short circuit before the 1979 Match Races, and after he zapped past my P&M Kawasaki TT F1 exiting Clearways setting off down the pit straight, I had a close-up impression of unbelievable acceleration, coupled with the ungainly-looking width of the two-wheeled Tamara’s rear end. By the time I exited Paddock Bend, Barry was turning into Druids – which probably says as much about our relative riding skills as the performance of the jumbo-Suzuki, but seemed pretty impressive at the time – especially as I never saw him wheelie the thing unduly, even when he passed me again about ten laps later….!

Riding an insane machine like the X23B and getting riding tips from of the best riders ever, Barry Sheene.

Fast forward a few decades, and after some tips from Barry himself before his sad death on how to ride the monster: “Concentrate on the midrange, which is what I used to do without using loads of revs, and don’t ever gas it up hard in the gears, because you haven’t got the ten-pound iron bar we fitted to stop it pulling wheelies – just ride the torque curve and short-shift to keep it cooking!”

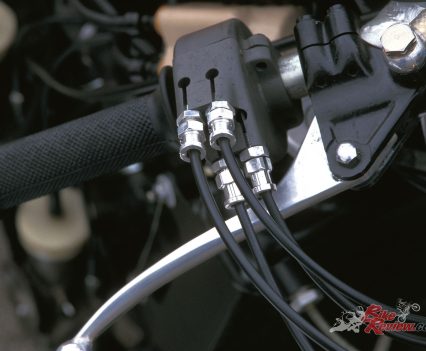

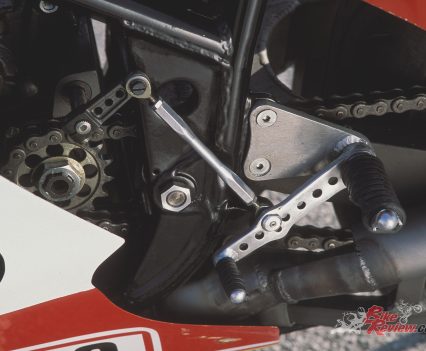

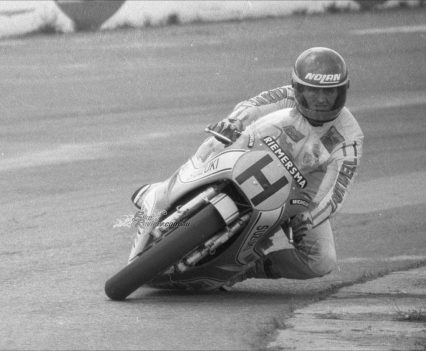

I could finally discover how it was to be like Bazza, and twist the wrist of the Suzuki-on-steroids. First problem is the strange and ungainly riding position, where thanks to those fat pipes behind your heels, you’re wedged in place and can’t actually put your toes on the footrests – you have to ride with your insteps on the pegs. This means you can’t move easily from side to side on the bike, and especially can’t hang off it, because you can’t get your toes on the rests. The throttle is surprisingly heavy, with the twistgrip operating four separate cables, one for each carb, while the steering damper strangely has only three clicks, so not much choice in settings on something you badly need to work properly on a bike like this which likes to reach for the stars in any gear!

“You have to ride with your insteps on the pegs. This means you can’t move easily from side to side on the bike, and especially can’t hang off it, because you can’t get your toes on the rests.”

Which it does, but only when you get hard on the throttle around 8,000rpm, where there’s a sudden hit of horsepower which will have the front wheel eagerly waving around your ears if you’re not careful – it’s a two-stroke wheelie-hound with a phenomenal power to weight ratio, and no powervalve to smooth out the power delivery.

Imagine having Barry Sheene trying to coach you on how to ride one of the most powerful bikes from the 1970s…

Then you’ll light up the rear tyre in a way that seems cruel and abusive punishment for the humble treaded Avon classic race tyre fitted to all Chris Wilson’s bikes. “I use these tyres on my Manx Norton, and they’re heaps better than anything we had back then,” asserted Mr. Sheene when I complained about grip. “You’re not riding it properly – stop using so many revs and ride the midrange torque curve to drive out of turns, rather than use launch control!”

“It’s a two-stroke wheelie-hound with a phenomenal power to weight ratio, and no powervalve to smooth out the power delivery.”

Trying to follow Barry’s advice made the Suzuki appear less brutal in its power delivery, easier to ride without sacrificing anything in the way of acceleration, simply because I was balancing grip with grunt and surfing the torque curve from 6,000rpm upwards. The trick was to avoid leaning the XR23B over too far on those relatively narrow tyres – look at period photos of Barry on the bike, and you’ll see he’s hardly hanging off it at all, even when it was fitted with the earlier, more manageable XR23A exhausts.

Just trailbrake deep into a corner – almost an inevitability with the weak response of those typically ineffective period Japanese steel discs, and their not very grippy two-pot calipers – get the Suzuki turned, and fire it out keeping it as upright as possible so as to use as much of the fat part of the skinny tyre as you can. Then you’ll revel in the phenomenal acceleration and marvel how well the Suzuki hooks up, especially considering the humble nature of the rubber – with due respect to Avon, this is surely much more of an explosive cocktail of performance and power than their classic race tyre was designed to harness, but it does the job just fine. Just so long you don’t crank it over too far and go off the edge of the tyre…..phew, saved it! When you do get a slide, it’s hard to correct it because of the ungainly wedged-in-place riding position, which makes shifting your body weight around so awkward.

The shift on the Suzuki was remarkably stiff! Sheene would head out last so he wouldn’t have to find neutral on the grid.

The one-up left-foot gearshift on the Hennen/Hartog bike (contrasting with Barry’s trademark right-foot change), was rather stiff – and it was completely impossible to find neutral, even rolling gently along with the clutch in, hunting for it with my foot. “Dead right – it was always like that,” confirmed Barry, “which is why I always made sure I was the last to leave for the warmup lap, and the last to get back there for the start. People used to think I was trying to get the opposition revved up waiting for me, but while that may have been an added bonus, the real reason was that I’d have to sit there holding the clutch lever in waiting for the guy to wave the flag – no lights then! Get there too early, and I’d fry the clutch – I was always complaining about this to Suzuki, but they never did anything to fix it.”

“Clutch action is nice, though – getting the XR23B off the mark is dead easy, until it comes to coping with the mega-wheelies you get in each of the bottom four gears.”

Clutch action is nice, though – getting the XR23B off the mark is dead easy, until it comes to coping with the mega-wheelies you get in each of the bottom four gears, just like one of today’s MotoGP bikes, except they have electronic engine management systems and traction control! The big hit of power that arrives at 8,000rpm certainly narrows your horizon, but changing up at 10,500rpm still leaves you in the heavy metal sector of the rev range.

There’s useful overrev, so holding a gear to save a pair of changes shows that the Suzuki doesn’t fall off the pipe once you get past the 10,800rpm peak power mark. According to the Racing Restorations dyno, there’s 125hp at the back wheel on this bike, the same as when Pat Hennen used to race it (Barry’s gave 129hp, according to the team records!). It still keeps pulling to nearly 12,000 revs, if you want to save a gearchange or are too busy struggling to keep it pointed more or less in the right direction. Best bet is to use the bottom two gears to get the Suzuki moving out of slow turns, short-shift at around 10,000rpm to third, then ride the torque curve and rev it out to around 11,500rpm, which it’ll happily pull while delivering really vivid performance by the standards of the era. Hold on tight!

However, the jumbo-Suzuki might have turned out even more of a two-wheeled tiger than it already was – as Heron Suzuki mechanic Martin Ogbourne, later to become the team’s chief GP race engineer, reveals. “Suzuki definitely built a full-size RG750,” he states. “They only made one, in the winter of 1976/77, but it was a proper stepped-cylinder rotary-valve 750 rather than a bored-out 500, and the first time they ran it on the dyno, it gave more than 150bhp. They knew there were no drive chains and no tyres that could be built to harness that kind of power back then, and certainly no brakes to stop it, so after a couple more tests the whole project was dropped, and they concentrated on improving the XR23B. Pity – Yamaha would’ve had no answer to that if the technology had existed to make it rideable!”

Kenny Roberts: “Thank heavens Suzuki never ran this at Daytona. But you have to ask yourself – WHY didn’t they ever race it in the USA? It would have given us a whole lot of trouble if they had of done….!”

Too true – so let’s leave the last word to Yamaha’s ace rival back then, Kenny Roberts: “Thank heavens Suzuki never ran this at Daytona,” says KR. “But you have to ask yourself – WHY didn’t they ever race it in the USA? It would have given us a whole lot of trouble if they had of done….!” That says it all!

1978 Suzuki XR23B RG650 Specifications

ENGINE: Watercooled rotary-valve stepped-cylinder square-four twin-crankshaft two-stroke, 652cc, 62mm x 54mm bore & stroke, Nippondenso CDI, 4 x 36mm Mikuni VM, 6-speed cassette-type extractable, Multiplate dry clutch (7 friction/6 steel)

CHASSIS: Tubular steel single-loop backbone with triangulated sub-frame and duplex engine cradle, 37mm Kayaba nitrogen-filled air-damped telescopic forks with inbuilt antidive system (f) Fabricated braced aluminium swingarm with 2 x Hagon shocks (r) 2 x 310mm Suzuki floating steel discs with two-piston Tokico calipers (f) 1 x 220mm Suzuki ventilated steel disc with two-piston Tokico caliper (R) 110/80-18 Avon AM22 on 2.50 in. Campagnolo cast-magnesium wheel (F) 170/60-18 Avon Am23 on 4.00 in. Campagnolo cast-magnesium wheel (r). 1395mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 125bhp@10,800rpm (at wheel), 309km/h, 136kg dry.

Owner: Chris Wilson, Broadstairs, Kent, UK.

1978 Suzuki XR23B RG650 Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.