The story of the Ducati 125 Regolarità has to be read to be believed. From four-stroke to two-stroke and back, it was the MXer that was years too late for Ducati and one of their biggest lemons... Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura/AC Archives

The return of Ducati to the MX and Enduro market dictates a look in the rear view mirror of history to back when the famous Italian sportbike manufacturer last previously dabbled in the offroad sector. Sir Al takes a ride in the rare Ducati 125 Regolarità…

Contrary to what its PR office state, the new Desmo450 MX model which the German-owned Italian sportbike manufacturer bills as ‘the first motocross bike in our history’ is in fact nothing of the kind.

British engineer Pat Slinn had a hand to play in two very different strands of Ducati’s competition history. While employed by Manchester dealer Sports Motorcycles, he worked alongside proprietor Steve Wynne in building Mike Hailwood’s 1978 Isle of Man TT F1-winning Ducati 900, then three years later helped him create the first-ever Ducati TT F2 World champion in 1981 out of a 500SL Pantah insurance write-off, which Tony Rutter then rode to victory in the Isle of Man xTT as the first of four TT F2 World title successes on desmo V-twins, latterly with factory-supplied Verlicchi-framed 600TT2 racers, which Slinn race-prepared.

Read Alan’s previous Throwback Thursday articles here…

But before that, in 1964, while working in the BSA factory’s competition shop, Slinn – an adept Enduro rider since an early age – rode a B40 British Army military prototype in the 1964 ISDT, held in in the DDR, where he gained a gold medal. “Not surprisingly, it was one of the bikes most photographed by local East Germans, who were probably all Stasi members!” recalls Pat.

Two years later in Sweden, he repeated his gold medal success with a BSA B44 Victor he’d built in his spare time – so while work commitments including a three-year stint in Germany working as a troubleshooter for the local BSA importer, meant he had no time to add to that tally by the time BSA went under in 1973, Slinn had considerable offroad experience when he joined British Ducati importers Coburn & Hughes as Service Manager in ‘74.

“I got to be friends with the Ducati factory engineers, who knew about my ISDT experience,” says Pat. “They’d just introduced this 125 Regolarità two-stroke Enduro model they wanted to promote it, and since the 1975 ISDT was going to be held in the Isle of Man, they asked Coburn & Hughes to let me ride one for them in that. We didn’t import them into the UK, because there was no market here for that kind of bike, but they still gave the OK. So I went over to the factory, met up with Italo Forni who was the guy they’d hired to develop it for them, and went riding it for a day with him up in the hills near Parma. It was quite different from anything I’d ridden before.

“The Italians thought it was a bit heavy, but they’d not grown up racing BSA pushrod singles!”

But I liked the way it handled – the Italians thought it was a bit heavy, but they’d not grown up racing BSA pushrod singles! My problem was the power delivery – it had no power at all low down – but then about 2,000 revs before the redline it took off like a rocket, and you just hoped you could hang on tight when it did so. It was an easy bike to wheelie, and that sort of power delivery was fine for hard, dry surfaces like you get in Italy, but I knew we’d have trouble in the kind of damp, wet going that’s typical in the Isle of Man in September. So I tried to make them understand they had to soften the power delivery to give it more traction and better rideability in sticky conditions. To their credit, they did a lot of development on ignition and port timing, and by the time we met up in the Island for the Six Days, it was quite a nice little bike they’d brought over for me to ride.”

So, Slinn was all set to complete a personal hat-track of ISDT gold medals with the Italian 125 Enduro, was he, then? Well – nearly, but not quite…. “It was the third day, the Thursday, and everything was going OK – I was on gold medal schedule, well up on time,” recalls Pat. “We were in the north of the Island, up near Ramsey, and I remember I was riding flat out in top gear – when it seized solid! I woke up much later and I honestly thought I was dead – I was lying on a bed, everything was green and misty, and it took me a while to realise that I wasn’t actually in heaven, but in Ramsey Cottage Hospital where the walls and ceiling were all painted that same sickly colour! It turned out the crankpin had locked up, so when Ducati rebuilt the engine they did so with more clearance on the bottom end, which was a mod they obviously adopted on the customer bikes, too. See, racing improves the breed!”

Once fully recovered, Pat Slinn was able to buy his rebuilt Ducati ISDT mount, bearing engine no. DM 125*130074 fitted in frame no. DM125C*130167, registered it in the UK with a British plate LRO 809 P, and rode it in British events for the next couple of years, gaining a Finishers Award in the tough Welsh Two Days Trial, then fourth overall in the gruelling ISCA Enduro, also held in Wales. But his best result with the 125 Ducati came in his last ride aboard it, when he won the Expert class in the British Army Enduro Championships on Pirbright Heath in Surrey, before selling it. By the mid-1980s it had ended up as some family’s funbike, but was fortunately acquired by Ducati specialist Mick Walker, who recognised what it was and restored it to the present original condition, before passing it on to an Italian bike enthusiast based in Ireland.

He won the Expert class in the British Army Enduro Championships on Pirbright Heath in Surrey…

From there, in 2000 it joined the magnificent collection of more than a dozen factory Ducati racers of all types housed in the Colección Can Costa in Barcelona, where it sits beside an example of each of the very different 125cc road racers the Bologna factory made in the 1950s – a 125 Grand Prix customer bike, a works 125 Desmo single, and the ex-Franco Villa/Bruno Spaggiari 125 Desmo twin. But that’s another story!

However, thanks to the owner of the bike, my mate Joaquin Folch, I was able to spend an hour or so riding the restored ex-ISDT 125 Regolarità very gently off-road around his country property outside Barcelona, and in something approaching anger on the roads outside. In doing so, I registered a personal milestone by riding a Ducati two-stroke for the first time ever in a ducatista lifetime – as well as discovering that everything I’d been told by the likes of Italo Forni and Pat Slinn about the bike being hard to ride, were absolutely true!

After you’ve coaxed it into life via the right-foot kickstart, and been rewarded with a spray of blue smoke from the fat Lafranconi exhaust that was a trademark of the bike even when new, the problem is the power delivery, which is worthy of a two-stroke GP racer of the era and I’ve ridden quite a few of these!

“In 2000 it joined the magnificent collection of more than a dozen factory Ducati racers of all types housed in the Colección Can Costa in Barcelona”…

Getting the Ducati off the mark at any kind of speed requires a big handful of the light-action clutch, otherwise it’ll start to trickle off the mark, then die away on you. There’s practically zero pull down low at anything but high revs – with no tacho fitted, just the minimal speedo needed to pass muster for UK licencing, it’s hard to know exactly when it comes alive, but I’d say you need 6,000 revs to go anywhere at all with the air-cooled single motor, which is all done soon after 9,000 rpm. First gear is surprisingly long, so the trick is to hold it what seems an unduly long time, before clicking swiftly through the 6-speed gearbox’s very precise one-down left-foot gearshift – the first ever on a Ducati motorcycle.

You can feel when the power starts to tail off that you’ve passed the 9,000 rpm power peak and it’s time to shift up – but it’s important to rev it right out in the gears to get worthwhile acceleration. Top gear is also very long, so the idea is to max out acceleration by revving it hard in the gears, then hope you’re going fast enough to pull that sixth gear in more relaxed lope-along mode. The engine is pretty raucous-sounding but quite well-balanced – there isn’t an excessive level of vibration.

“The engine is pretty raucous-sounding but quite well-balanced – there isn’t an excessive level of vibration.”

With chunky period Pirelli rubber on the Akront rims, there was good grip trailbiking offroad through the Folch orchards, at the expense of onroad feedback in turns – those trips to the beach or disco with his best babe sitting behind him would have been a little fraught for Ducati’s 16-year old target customer, if it came to getting it on with anyone aboard a tarmac-focused mini-sportbike. But those small brakes don’t give much confidence in street use, and with the very un-ducatiesque situation of having zero engine braking on tap, you need to squeeze very hard indeed to anchor up to avoid a Barcelona taxi making an unscheduled and unsignalled stop to pick up a fare.

Of course, the wide Magura handlebar delivers lots of leverage, so last-minute avoidances are still possible, and with the narrow 21-inch front wheel the steering is pretty light – the Regolarità goes where you point it onroad despite what looks like a pretty raked-out head angle, and lots of trail. Offroad, I defer to Italo Forni, who said it had heavy steering in this pre-Six Days first series form – but then he’s a hero who rode the wheels off it, whereas I was just gently picking my way through the pear trees in the Can Costa orchard…..

the wide Magura handlebar delivers lots of leverage, so last-minute avoidances are still possible, and with the narrow 21-inch front wheel the steering is pretty light.

Five decades on from when the 125 Regolarità was launched, we have a clearer idea nowadays of what we expect a Ducati to be – and it’s not like this. Look – maybe it’s just as well the last Ducati two-stroke ever made was a flop. Or else, instead of a succession of glorious desmo V-twin Superbikes, Ducati might have gone the Aprilia route, and built a succession of two-stroke 125/250 GP road racers and off-roaders, instead of their succession of glorious desmo V-twin Superbikes. Yes, definitely a good thing, then…

DUCATI 125 REGOLARITÀ TEST: Skeleton in the Cupboard

Lots of famous makes have skeletons in the cupboard, models they’d rather you didn’t know they ever made. Like the 50cc moped and 98cc scooters that MV Agusta produced back in the 1950s, or Moto Guzzi’s three-wheeled delivery truck, or Suzuki’s flawed TL1000 V-twin sportsbike – or indeed the smallest Norton ever sold, the overweight, unreliable Jubilee 250 twin, whose copious oil leaks stained many a British driveway.

Or – but you get the picture. So how about the Ducati single-cylinder Enduro/MX model of which 3,846 examples were built from 1975 to 1979, which was also incidentally the first Ducati motorcycle to be built with a left-foot gearchange? It wasn’t just the fact that the 125 Regolarità and its later Six Days variant represented the Bologna factory’s only serious attempt to target the offroad market, but it was that contradiction in terms – a Ducati two-stroke!

“3,846 examples were built from 1975 to 1979, which was also incidentally the first Ducati motorcycle to be built with a left-foot gearchange”.

It’s true that, like the dozens of other Italian makes trying to carve a slice of the country’s huge appetite for affordable personal transportation in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Ducati had earlier made several eminently forgettable 50-100cc two-stroke models, from the Brio scooter to the Rolly moped, the Mountaineer high-handlebar commuter to the Brisk single-speed runaround, whose names alone defied all known truth-in-advertising regulation, yet which collectively represented the major part of Ducati production in the 1960s. But by 1975 when the 125 Regolarità was launched in the marketplace, Ducati had moved on, and was now well established as the leading Italian four-stroke performance brand, with a twin-cylinder sportbike range derived from Paul Smart’s V-twin Imola 200-winner.

The idea that it should ever have tried to carve out a slice of the then-booming 125cc enduro market for sixteen-year olds peopled by 23 other makes from Ancilotti to Zündapp, via Aprilia and Beta, SWM and Sachs (whose well-regarded two-stroke single motor powered much of the competition), Montesa and Fantic, etc., seems very – well, short-sighted, let’s say.

But by 1975 when the 125 Regolarità was launched in the marketplace, Ducati had moved on, and was now well established as the leading Italian four-stroke performance brand.

Mind you, bureaucrats have never been much good at running bike companies, and ever since 1967 Ducati had formed part of the Italian government’s EFIM (Ente Partecipazioni e Finanziamento Industria Manifatturiera) state-owned conglomerate responsible for the day-to-day operations of the company and 114 others within Italy. However, it had the good fortune to see Fredmano Spairani appointed as its CEO in 1969, a professional manager with an open mind as well as some flair, who listened, learnt and acted on what he was told.

Ducati progettista Fabio Taglioni and his colleagues convinced Spairani of the values of a product-led strategy based on the large capacity 750cc four-strokes that BSA-Triumph and Honda had just launched, underpinned by a factory race programme, and that’s how the family of 750cc V-twin Ducatis that debuted in 1971, came about. Unfortunately for Ducati, Spairani’s success in spearheading the company’s transformation (even if production was slow to build up sufficiently to take immediate advantage of that success) meant he was appointed in 1973 to try to pull the same trick on Agusta’s aviation and motorcycle business, which had also fallen under EFIM control – and his elderly, short-sighted successor Cristiano de Eccher was only concerned with numbers, not product. So at his specific behest two new model platforms targeted at volume market segments were created that are today regarded as eminently forgettable postscripts of Ducati history – the 350/500cc parallel-twins, and the 125 Regolarità two-stroke Enduro.

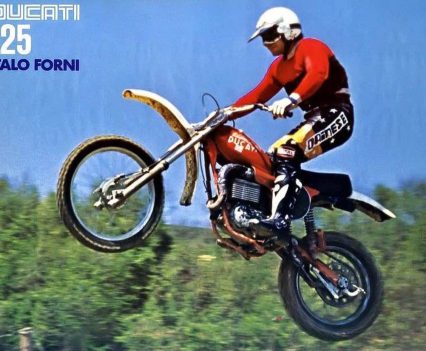

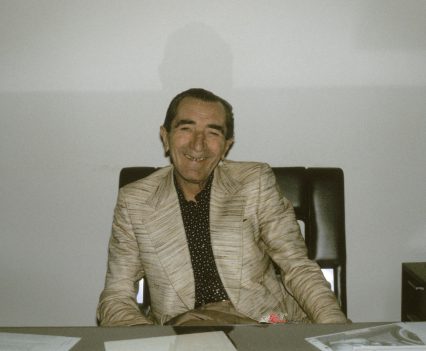

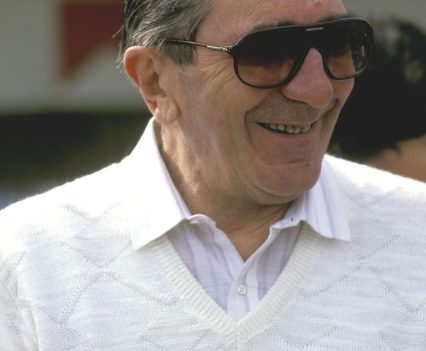

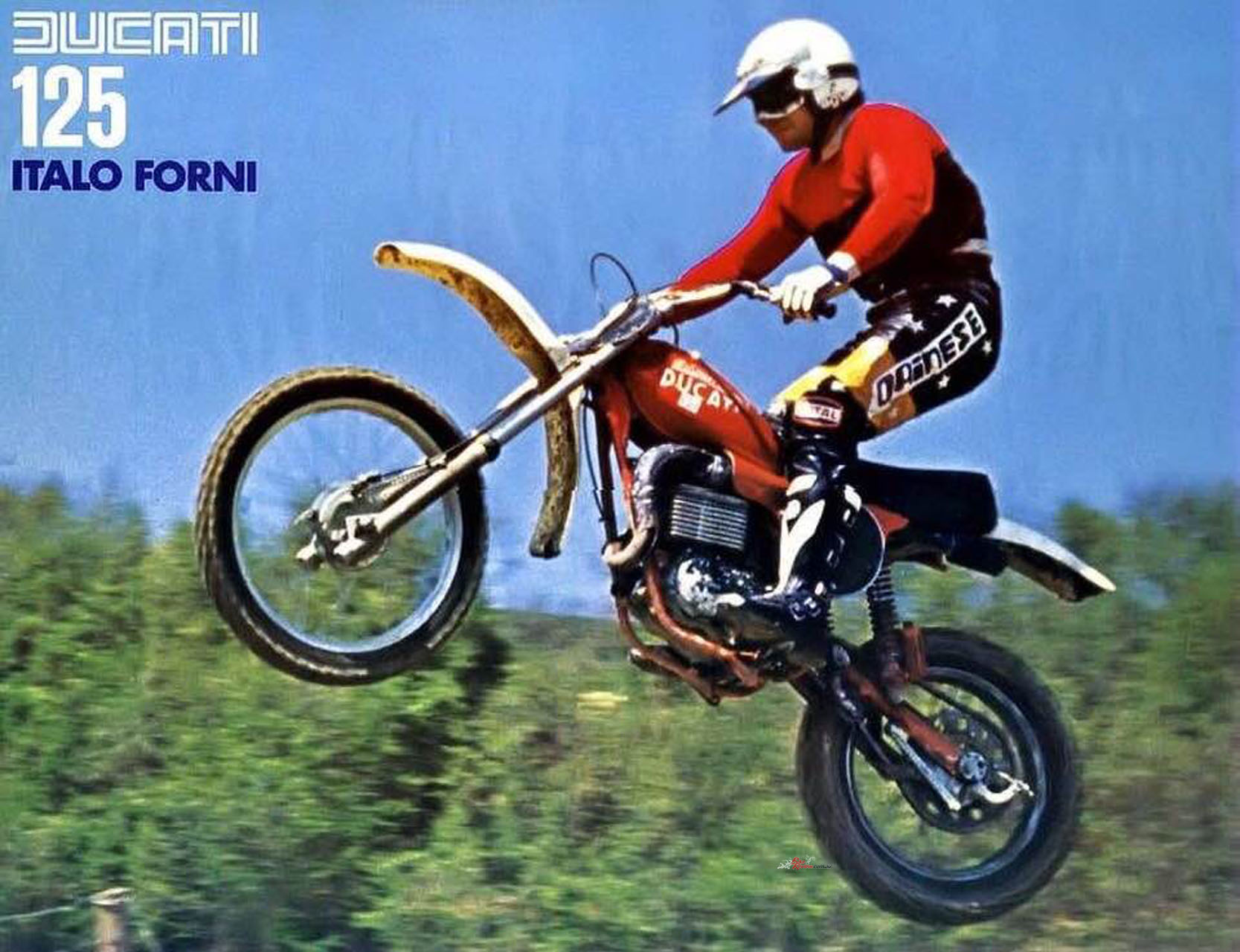

Italo Forni, the legendary Italian MX and Enduro 125, 250 and 500cc superstar in 1977 on the Ducati 125.

Italo Forni was Italy’s star off-roader of the 1970s, a multi-time Italian MX and Enduro champion in the 125/250/500 categories, and at various times a works rider for Honda, KTM, CZ, Montesa, Kawasaki (he was the first European rider to be signed by the Japanese factory), Moto Villa (for whom he won 36 races in 38 starts in 1972) – and Ducati. Today an active 73-year old who’s enjoyed a series of key roles in the Italian bike industry since retiring from racing in 1980 while still at the top, Forni was the man Ducati engineers recruited back then to help them develop a product for a market sector they had no experience of at all, but which de Eccher had insisted must be addressed in Ducati’s catalogue – a streetlegal 125cc enduro dirtbike.

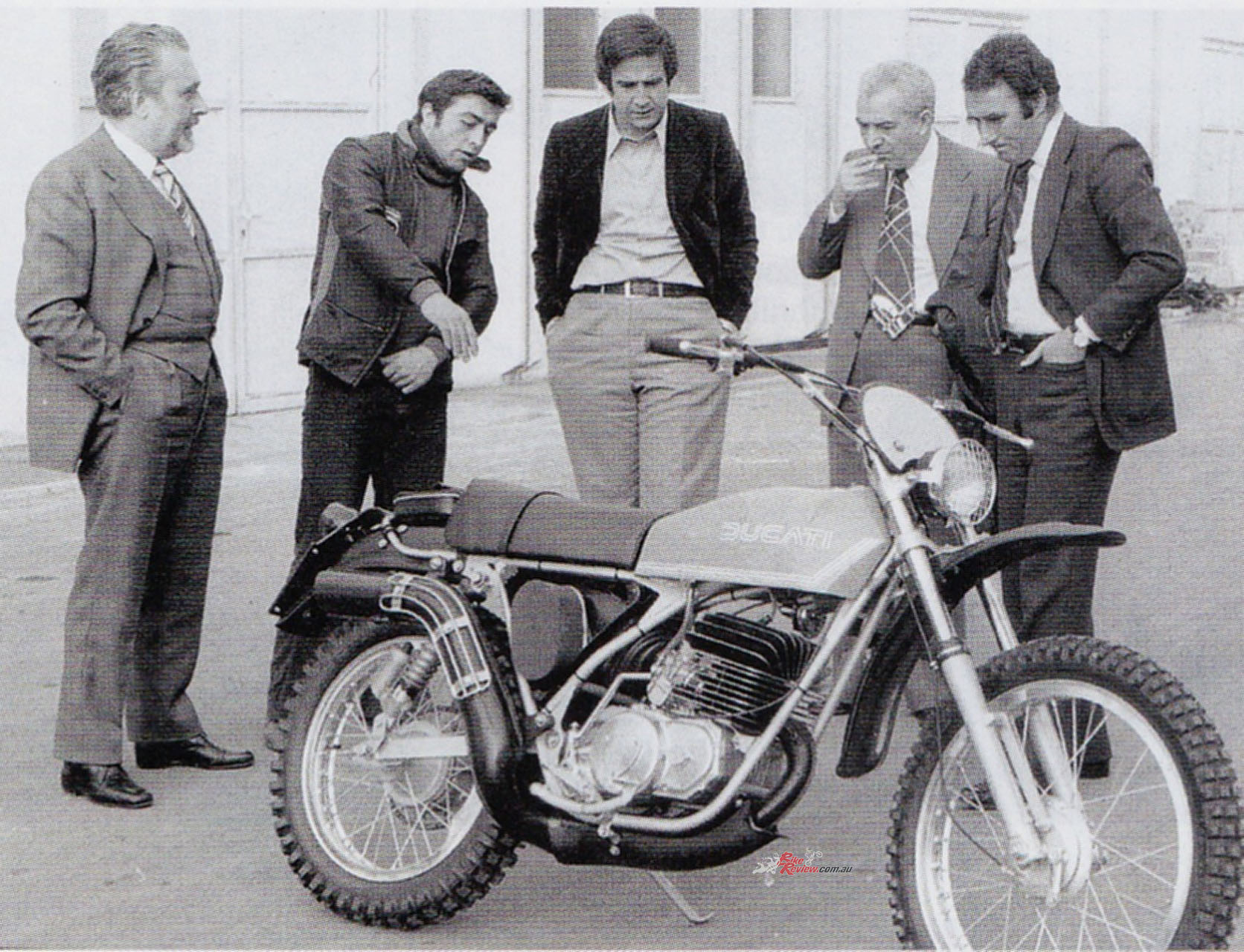

“Ducati contacted me in 1973 to ask them to help develop an Enduro,” recalls Forni, “so I went to Bologna to meet Taglioni and Cosimo Calcagnile, the Commercial Manager. Taglioni had designed an all-new single-cylinder four-stroke engine to replace the wide-crankcase Mark III singles which were just then ending production, and he’d wanted to use this to develop a range of 250 and 350cc bikes for the Enduro market, to follow on from the successful Scramblers. Spairani had been favourable to this idea, but the new guy refused to consider it – he considered himself an expert on the market, and that meant it had to be a 125 two-stroke, because that was what everyone else was selling. Never mind about Ducati’s inexperience in this sector, or the reduced profit margins in such a competitive marketplace!

“Taglioni had designed an all-new single-cylinder four-stroke engine to replace the wide-crankcase Mark III singles which were just then ending production”… “but the new guy refused to consider it”…

So Taglioni and his colleagues in the Reparto Sperimentale decided to use the bottom half of that new four-stroke engine for such a motor, but to fit it with a two-stroke top end – and since they neither knew nor cared much about two-strokes, they simply used the most successful engine in the sector as a reference, which was the Sachs. That’s why the Ducati two-stroke has the same radial cylinder head finning as the German engine, why the crankcase is so wide and heavy for a 125 two-stroke, and why the crankshaft and transmission are also over dimensioned – they were designed for a bigger four-stroke engine. People always thought this was because Ducati planned to make a future 250cc version possible – but I assure you that was never the intention!” However, de Eccher had originally intended to make a conventional 125cc road bike using the same two-stroke engine, but this idea was dropped.

“They simply used the most successful engine in the sector as a reference, which was the Sachs. That’s why the Ducati two-stroke has the same radial cylinder head finning as the German engine”…

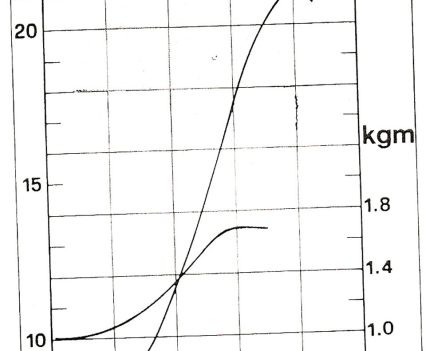

Launched in April 1975, the 125 Regolarità had an air-cooled piston-port motor with ‘square’ 54 x 54 mm dimensions, originally with four transfer ports and a single exhaust in the Gilardoni cylinder’s cast-iron sleeve, then later with twin additional boost ports. Fitted with a 30mm Dell’Orto FHB carb with lift-up choke lever, and running a high 12.4:1 compression after the 10.5:1 ratio the bike was launched with had to be raised to give a much needed boost in acceleration, the engine produced 21.8 bhp at 9,000 rpm at the gearbox – comparable with the competition, but with a narrower power band compared to the pre-eminent Sachs motor it had attempted to copy, and maximum torque of just 1.7 kgm/16 Nm/11.8 ft-lb at 8,000 revs.

The 109kg dry weight was heavy by class standards, ten kilos more than most of its competitors…

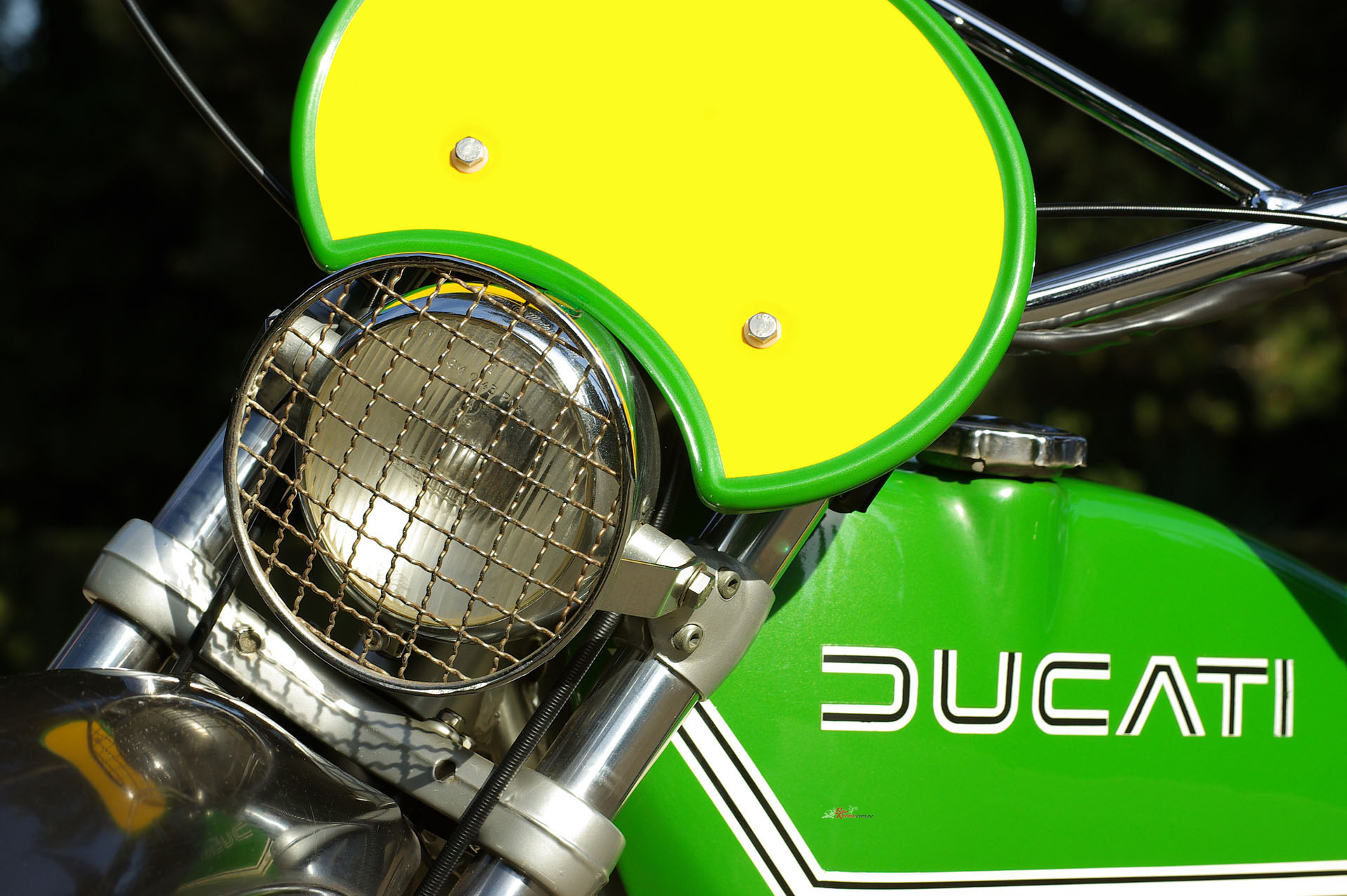

The heavy duty six-speed gearbox and oil-bath clutch – remarked on by contemporary testers as “quite capable of harnessing more performance from a larger capacity engine”! – were needed to coax available performance from the engine. For the 109kg dry weight was heavy by class standards, ten kilos more than most of its competitors, plus the fact the 125 Regolarità was homologated for a passenger was advertised by a non-streetcred strap across the 850mm high dual seat, and there was a battery behind the left side numberplate to power the small headlamp with its smart but heavy steel grille (the detachable air filter was housed on the opposite side). The Motoplat CDI running 19° of ignition advance had a flywheel generator that ensured the Ducati two-stroke motor could run without the battery, meaning the exposed ignition key on the left side was only needed to turn on the lights! But it seemed strange Ducati needed to import the new bike’s ignition system all the way from Spain, rather than source the equivalent from its Ducati Elettronica sister company literally right next door in Bologna, unless it was the fact that Sachs used a Motoplat CDI too!

The enduro Ducati’s twin-loop Verlicchi mild-steel frame was surmounted by a slab-sided six-litre plastic fuel tank filled with 5% mixture, which proved to be on the small size once magazine tests revealed a thirsty 7.5lt/100km fuel consumption, or 38mpg Imperial/31mpg US – high for a 125 enduro. The chassis carried 35mm Marzocchi forks offering 180mm of wheel travel, with at the rear a box-section steel swingarm with twin Marzocchi piggyback air/oil shocks with remote air chambers running 2.0kg/cm² pressure, five-position spring preload adjustment, 130mm of wheel travel, and a choice of three upper mounting positions.

But the routing of the fat Lafranconi exhaust (with a detachable rear section to allow for repacking) beneath the engine was a real handicap, says Forni. “At the direction of the management, the first version of the bike was really more of a streetbike than a competition enduro model,” he says. “But Ducati owners love to race, even on a two-stroke, so it soon became obvious there were several changes we’d have to make to reflect this.” Yet the tiny 125mm Grimeca single leading-shoe drum brake with conical hub fitted to the 21in front wheel was definitely undersized for street use, especially with a passenger and even when its slightly larger 140mm rear companion on the 18in wheel was used hard – and with a class-leading top speed of 119 km/h in independent tests, the 109kg Ducati needed some stopping.

However, the Akront alloy rims, Magura handlebar and levers, Aprilia switchgear and headlamp, Preston Petty flexy plastic mudguards with a small zip-up documents pouch on the rear one, Arieto numberplates and Nino Verlicchi spring-loaded footrests, were all quality components on an entry-level bike that was competitively priced versus its competitors at Lire 868,000 incl. tax – the Sachs-powered KTM GS125 was more than 20% most expensive, albeit 25% lighter and 10% more powerful than its Ducati rival….

In order to gain some two-stroke credibility with potential customers in a segment where up till now it hadn’t featured, Ducati supported various 125 Regolarità riders in local Italian Enduros and in France, the only other country the model was catalogued in. That extended to the 1975 ISDT in which the test bike competed, but success was slow in coming. Italo Forni was thus hired by the factory to race the Regolarità in the 1976 Italian MX and Enduro championships, as well as compete in the ISDT in Austria – in the course of which he developed an uprated version which Ducati introduced for 1977 under the Six Days label, replacing the previous model.

Italo Forni was thus hired by the factory to race the Regolarità in the 1976 Italian MX and Enduro championships

Boasting more aggressive offroad styling with an 8-litre aluminium fuel tank and black-painted motor, the new bike came in two versions, Cross and Regolarità, each with revised porting for the new chrome-bore cylinder and altered ignition timing, which coupled with a new design of combustion camber and piston with more squish, a larger 32mm carb, and compression raised to 14.6:1, delivered a healthy claimed power increase to 25bhp at 10,250 rpm. The weight issue was addressed via a chrome-moly frame, magnesium sliders on the Marzocchi forks, and measures such as a much-lightened steel clutch basket shot full of holes to combat the kilos, down from 1.32kg to 0.98kg.

Dry weight was slashed to a claimed 99kg, which actually turned out in magazine tests to be 104kg, but the front brake was increased to 140mm in size, and most important of all the exhaust was rerouted to run up and over the top of the cylinder, exiting under the seat on the left. The price was however raised to a more realistic Lit.1,271,100 that was comparable with the competition – it’s doubtful that Ducati made much profit out of the 2,786 examples of the 125 Regolarità it made and sold in 1975-76.

Dry weight was slashed to a claimed 99kg, which actually turned out in magazine tests to be 104kg, but the front brake was increased to 140mm in size, and most important of all the exhaust was rerouted to run up and over the top of the cylinder, exiting under the seat on the left. The price was however raised to a more realistic Lit.1,271,100 that was comparable with the competition – it’s doubtful that Ducati made much profit out of the 2,786 examples of the 125 Regolarità it made and sold in 1975-76.

“The Six Days was a much more competitive mount,” says Italo Forni. “It had an improved riding position because of a better shaped fuel tank and the tucked in exhaust. However, it was still rather fragile, and was quite highly stressed to deliver competitive performance, although by the middle of 1977, we’d begun to win races with it. But the sales had failed to meet expectations, so just as we had it coming good, EFIM decided to end the project! The original Regolarità model had lost Ducati credibility, in giving the impression it didn’t know or care about Enduros – which was indeed partly true! It was born out of a compromise, because the EFIM management wanted to have a streetbike that their 16-year old customer could ride to the café with his girlfriend sitting behind him, yet could also win races – and in the 1970s 125cc offroad sector, that didn’t happen, because there were some very specialised rival products.

“It was too bulky, and too heavy to ride – indeed, it was quite old-fashioned even by mid-‘70s standards”…

“It was too bulky, and too heavy to ride – indeed, it was quite old-fashioned even by mid-‘70s standards. It had a very peaky power delivery because to get the necessary engine performance, they had to narrow the powerband, so there wasn’t much torque, which in Enduro is a problem. It was actually better as a motocrosser, once we started removing weight, and those were the races I won on the bike before they closed everything down. Ultimately, it had everything it needed to be successful, but it just wasn’t thought through properly at the beginning – probably because Taglioni hated two-strokes, and resented being forced to produce this model, even if he did redesign the engine in 1976 to produce a smaller, lighter version. But because of the disappointing sales, the budget wasn’t there to re-tool to produce it, so it never happened. If this had powered the Regolarità from the outset, it would certainly have been more successful than it was.”

“In 1979 the defunct engine project was acquired from Ducati by Leopoldo Tartarini, the owner of the Italjet factory located at San Lazzaro di Savena”…

Still, that wasn’t the end of the Ducati 125 Regolarità story – for in 1979 the defunct engine project was acquired from Ducati by Leopoldo Tartarini, the owner of the Italjet factory located at San Lazzaro di Savena, on the other side of Bologna from Ducati’s Borgo Panigale base. He’d raced for Ducati as a factory rider in the 1950s, before undertaking a remarkable 13-month round-the-world trip in 1957/58 with a colleague on a pair of 175cc Ducati singles, a trip which brought the marque untold publicity that helped it stand out from its dozens of competitors just as it was getting established as a sporting brand.

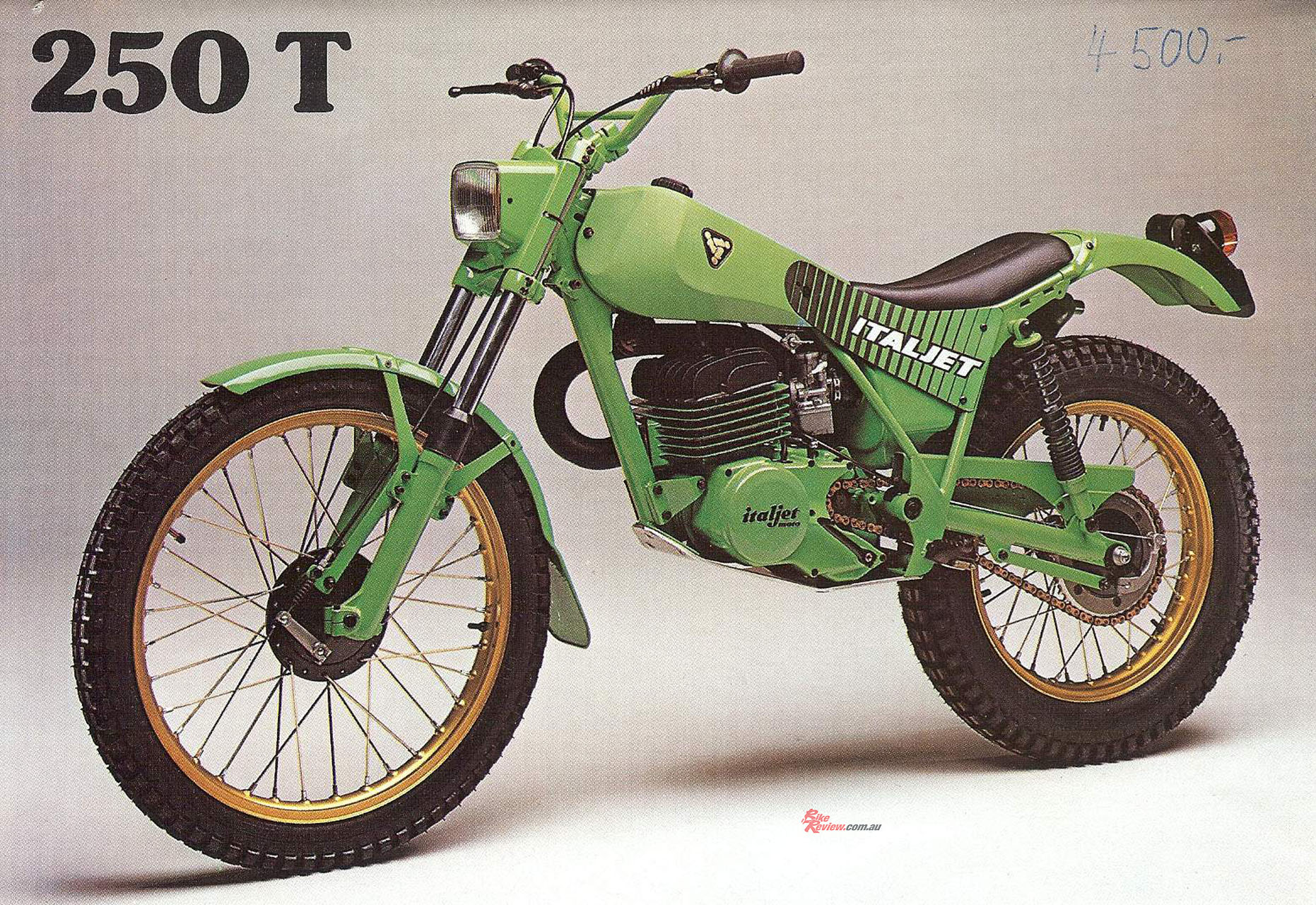

By the late ‘70s, Tartarini’s talents for building good-looking, fine-handling bikes of all capacities under the Italjet label – most notably the acclaimed Triumph Bonneville-engined 650 Grifon – were well established, leading to a close collaboration with Ducati, for which he designed all the Mark III singles, including the iconic Scrambler, as well as Taglioni’s new range of 750cc V-twins, most notably the glorious 750SS green-frame desmo Imola replica. The lean, cobby looks of this most desirable of bevel-drive Ducatis were entirely owed to Tartarini, a self-effacingly modest forerunner of Massimo Tamburini and Pierre Terblanche, who could ride as hard and as well as he wielded a pencil. “Ducati in those days were mainly engine manufacturers,” Tartarini explained to me before his sad passing in 2015, aged 83, “so they had no design studio and only a very limited production capacity for complete motorcycles, because they were too busy building diesel engines for automotive and industrial use, alongside the bikes. Because of my earlier connections with the firm, Italjet was called on to design not only the street singles, but all the early Ducati V-twins, based on Ing.Taglioni’s engine and chassis layout. Then, later in the decade, we not only designed the frame and the styling for the range of Ducati parallel-twins, but actually manufactured the bikes ourselves in the Italjet factory in San Lazzaro, using engines trucked across town from Ducati.”

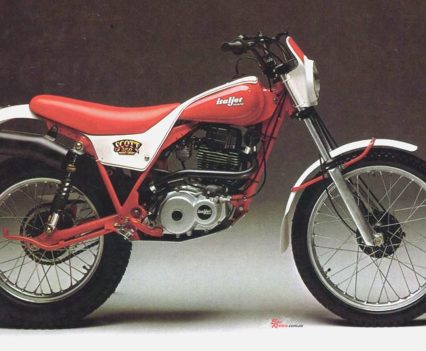

This close relationship, and the demise of the Enduro project, meant that Italjet was able to acquire the 125cc two-stroke engine design in all its various forms from Ducati, badged with its own name for use in various models – and doing so neatly squared the circle for company boss Leopoldo Tartarini. “I was aware of the Regolarità’s engine from its four-stroke origins,” he explained, “so I knew it had a very strong bottom end design that was capable of handling a lot more power, whether two-stroke or four-stroke in derivation, in the category I wanted Italjet to attack – this was the Trials sector, that was then gaining fast in popularity. So early in 1979 I therefore acquired all the Regolarità’s engine drawings and patterns, and modified it to produce three new engines all using the same Ducati 125cc base – a 350 two-stroke, a 250 two-stroke, and a dry sump 350 four-stroke with a single overhead camshaft that delivered 38 bhp. I used this in the Italjet Scott trials bike that debuted in 1983, of which we made about 100 examples, and Taglioni was especially pleased to see this, because it represented the form in which he had always intended the engine to appear.”

However, three years before this 80 x 64 mm 322cc four-stroke version that was more of a trailbike than a trials bike appeared, the 250cc/350cc two-stroke variants had made their debut in Italjet’s distinctive bright green Trials models which debuted in 1980 alongside a pair of Minarelli-powered 50/125cc models. Italjet had previously been the Italian importers for Bultaco, for whom 20-year old American Bernie Schreiber had won the 1979 World Trials Championship, but with the Spanish firm bankrupted by rising debt and political uncertainty, Schreiber moved to Italy to develop the new Italjet bikes. He finished second to Montesa’s Ulf Karlsson in the 1980 World series on a 326cc version powered by a larger capacity version of the 6-speed Ducati-based engine measuring 83.2 x 60 mm – a smaller 71mm-bore 237cc version was also developed, and both offered for sale, with around 1,000 examples in all built and sold, according to Tartarini. For 1981, Italjet produced an improved, lighter version, of the T350, but Schreiber could only finish sixth in the World Championship, and his move to the rival SWM concern marked the end of Italjet’s World Trials involvement.

It was also the end of the road for the Ducati two-stroke project – one that can only be characterised as confused, having started out as a four-stroke, entered production as a two-stroke, then given away for adoption like a problem child to a satellite company that actually did OK with it in the end. And in doing so, it actually ended up coming home – because it was Italjet boss Leopoldo Tartarini who designed the original 125 Regolarità for Ducati! “I did it over a long weekend late in 1974,” recalled Leopoldo, “and the man who helped me design it was Joe Berliner, Ducati’s American importer. At that stage there was a chance that he might import it into the USA, where the two-stroke Enduro market was now an important market sector, so he worked with me in styling it in – he was very intelligent and passionate about design, maybe surprisingly so for such a hard-headed businessman. But in the end they decided just to concentrate on the V-twins – but we created the Regolarità together!”’

But that’s not quite the end of this multi-faceted story – for as Italo Forni recounts, in 1975 he and Ducati R&D engineer Franco Farnè developed a four-stroke Enduro model for Ducati’s Spanish affiliate Mototrans, complete with disc brakes, monoshock frame, and an all-new 500cc bevel-drive SOHC engine which Taglioni had produced, using many parts and much technology from the 864cc version of the V-twin engine that was by then in production. This four-stroke Enduro was conceived one year before the XT500 Yamaha appeared which duly became the class benchmark, and was apparently a very small, light, advanced design which was not much bigger than a 125 Husqvarna. “We built two prototypes which went to Spain, but the reason it never entered production was because of Mototrans closing down,” says Forni. “This was a very good bike which pre-dated the arrival of the four-stroke Enduro boom – ironically, the EFIM guy who insisted that Ducati should build an Enduro bike got it right, but he should have let Taglioni do it the Ducati way and build a four-stroke, in which case they would have led the world!” If only!

DUCATI 125 REGOLARITÀ – Specifications

Engine: Air-cooled single-cylinder piston-port two-stroke, four transfer ports and single exhaust port, 54 x 54mm bore x stroke, 123.7cc, 12.4:1 compression ratio, 1 x 30mm Dell’Orto PHB carburettor, Motoplat CDI with 6V battery and flywheel generator, six-speed gearbox with helical gear primary drive, wet multiplate clutch, exhaust system standard.

Chassis: Verlicchi tubular steel twin-loop frame with reinforced single-tube backbone, box-section steel swingarm with twin Marzocchi air/oil shocks (remote chambers, 130mm travel), 35mm Marzocchi telescopic forks (180mm travel), 1420mm wheelbase, 850mm seat height, 125mm Grimeca single leading-shoe drum with conical hub (f), 140mm Grimeca single leading-shoe drum with conical hub (r), 2.75 x 21in Pirelli Trail On/Off on WM1/1.60in Akront aluminium wire-spoked rim (f), 4.10-18in Pirelli Trail On/Off on WM2/1.85in Akront aluminium wire-spoked rim (r).

Performance: 109kg dry weight, top speed 119km/h (74mph), 21.8bhp@9000rpm (at gearbox), 16Nm@8000rpm.

Owner: Colección Can Costa, Barcelona, Spain