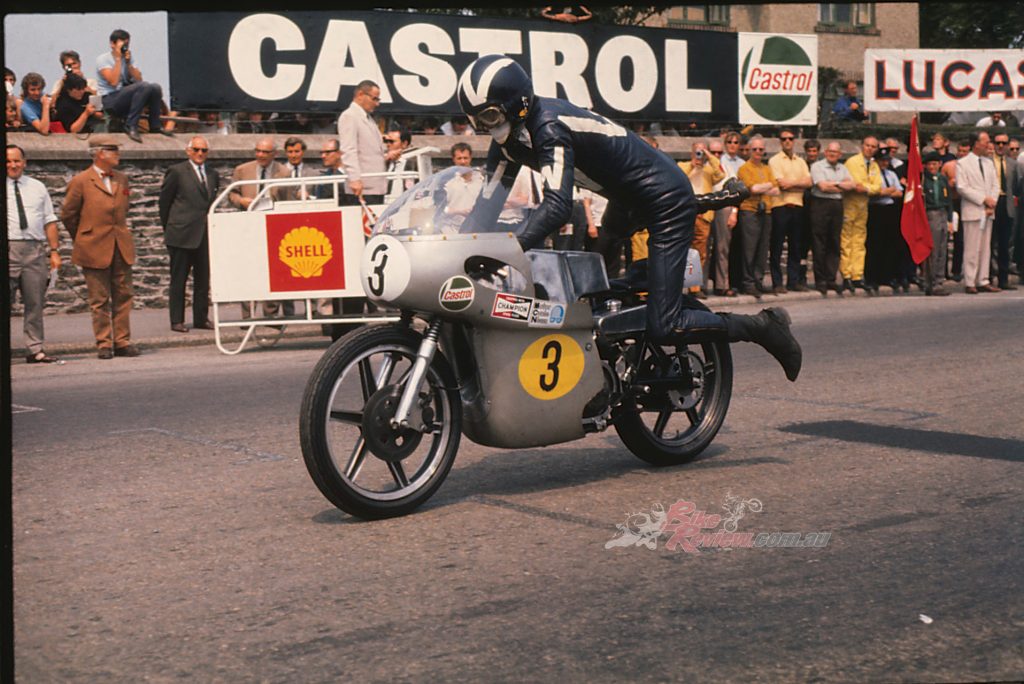

Britain’s Peter Williams, widely acclaimed as the finest GP racer/engineer of modern times, passed away quietly in his sleep just before Christmas, this was his story of rising to the top... Words: Alan Cathcart Photos: AC Archives

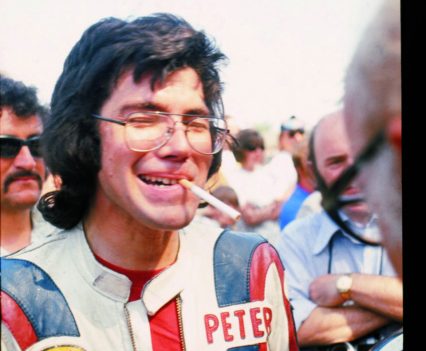

Peter Williams or “Pee Jay”, as he was known after his initials PJW, was 81 years old, and will be revered for his unique combined talents as an innovative designer, and a top level road racer, as well as a gregarious, affable individual who made friends easily.

Yet at various times in his career, whether out of patriotism, loyalty or misfortune, Williams turned down the chance to race for the works Suzuki GP team, forfeited a season-long GP ride with the Honda factory, and declined an offer to work as a designer for Yamaha. Instead, he waited for a 250cc race at Daytona in 1967 on a works Kawasaki which lasted just one lap, and a couple of MZ rides.

During one MZ ride he scored the East German factory’s final GP race victory in the 1971 350cc Ulster GP, which was also his own solitary World Championship race win. Williams raced only British bikes during his entire eleven-year racing career, which ended in August 1974 with his tragic Oulton Park accident on the spaceframe F750 John Player Norton.

Born in 1939 in the week before the outbreak of WW2, Peter was the son of Jack Williams, creator of the Matchless G50. During his time as chief engineer for AMC/Associated Motor Cycles, Jack Williams also supervised development of AJS’s World title-winning Porcupine 500cc twin and Junior TT-winning 350cc 7R single. After training as a draughtsman, Peter initially worked in the Ford car factory’s drawing office at Dagenham, while starting to race motorcycles quite late in life, aged 24. His father had always discouraged him from racing, and instead pushed him to be an engineer.

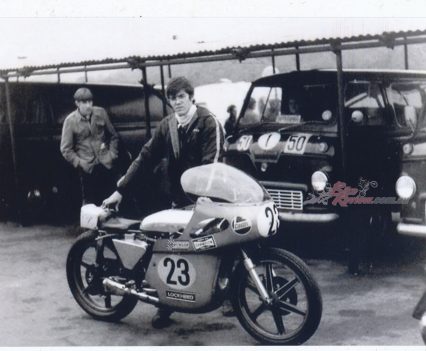

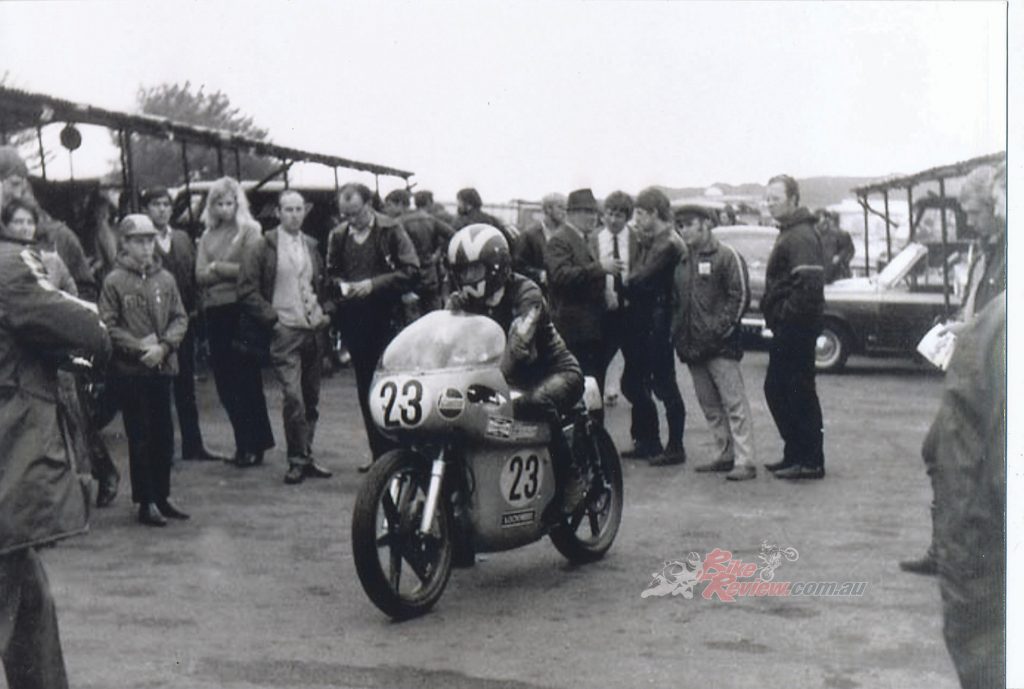

“I didn’t start racing until my friend Michael Tooze left University in 1963 and got himself a racing bike, and I thought if he could do it, so can I,” Said Peter. “Since he bought a 500 Manx Norton, I got a 350 Manx so we’d be in different classes, and could help each other. I came fourth in my first race at Snetterton that October, but he won his, so we both came home happy. But he never won another race, and I did.”

1964 saw Williams learning the ropes of the racing game on his 350 Manx and a 500cc BSA special built by Tony Wood, another friend. The pair combined to race an AJS 250 CSR single supplied by Peter’s father but prepared by legendary tuner Tom Arter, in the Thruxton 500-Mile race, then the most prestigious and gruelling box-stock Production event on the calendar.

Using standard Dunlop road tyres in the unexpected absence of any race tyre service – at this FIM Endurance Championship round – the duo opted to race as far as possible on the same rubber until the white canvas started showing. But it only did so on the last 10 laps, so they finished 7th overall and won the 250cc class, beating Honda and its star rider Derek Minter into second place. Less than a half-dozen races into his career, Peter Williams was invited to race in that July’s Barcelona 24 Hours – his first International race.

“Nowadays I wouldn’t have been allowed to go, since I’d only be a Novice and not done enough races,” he said. “But in those free and easy pre-Health and Safety days, it was OK!” The pair rode the same standard AJS 250 now fitted with race tyres, despite chronic brake and gearbox problems, they finished the race. Peter Williams was then still working at Dagenham, with Henry Ford unwittingly sponsoring his racing career via unofficial time off.

“People think I went to University, but I never did… I was offered a scholarship to Woolwich Polytechnic, but I turned it down because I had to go racing.”

During 1965 Williams gradually worked his way up the finishing order in hard-fought British short-circuit racing, while after a DNF on the Norton on his Isle of Man debut in the 1964 Manx GP, he finished third in the ’65 Lightweight Manx on a 250cc Greeves Silverstone two-stroke single. This resulted in an offer from Bert Greeves to join the small Essex manufacturer as Design Draughtsman, on the same money as his Ford job, but with the time to go racing officially set aside. This led to the watercooled Greeves 250cc works road racer he helped develop, then claimed victory in 1966 at Brands Hatch.

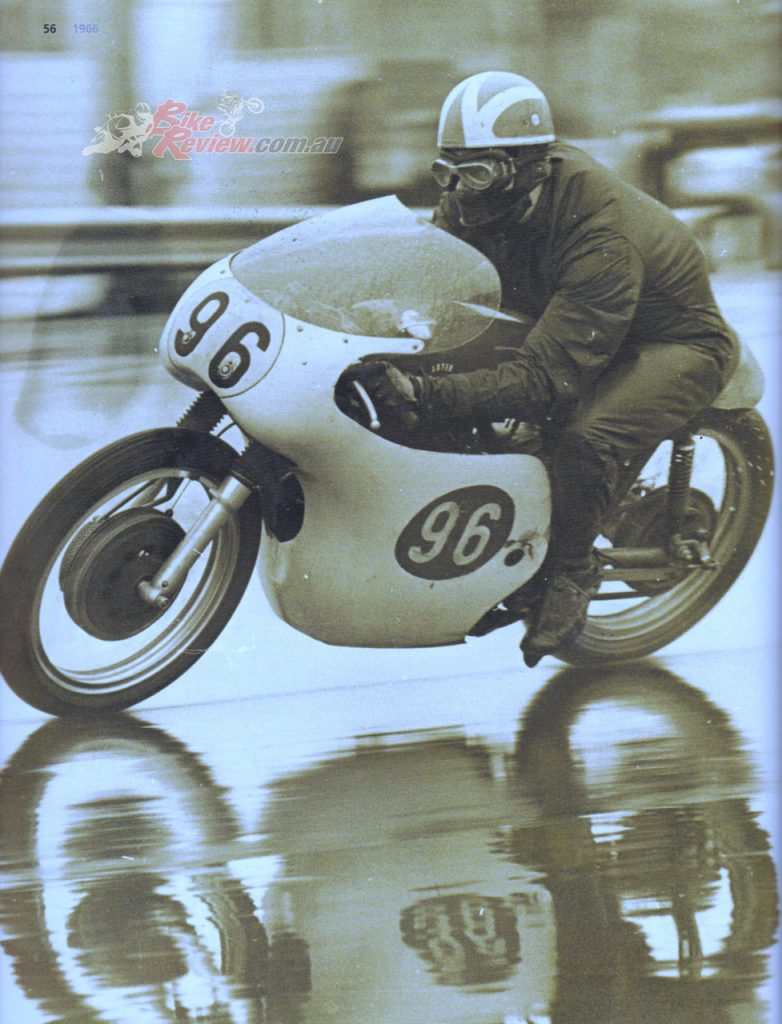

By then Peter had stepped up to the top level of British GP riders, after Tom Arter asked him to succeed Canadian Mike Duff. He was now riding for the factory Yamaha GP team, racing Arters bikes in 1966, including the Reynolds-framed AJS 350 built by John Surtees with a 7R engine he’d obtained from Peter’s father, on which Duff had finished third in the 1964 350cc World Championship.

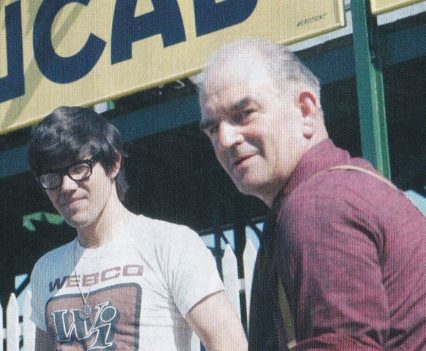

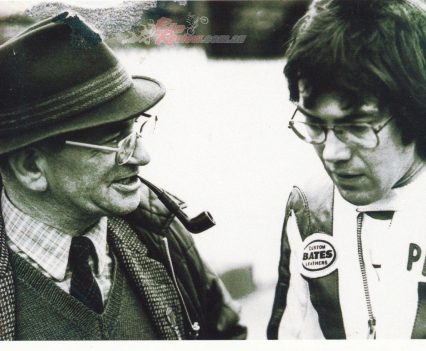

Williams rode the Arter AJS to a debut victory in pouring rain at the final Mallory Park National of 1965, then again in the dry the following weekend at Brands Hatch. This led to an eight-year partnership between the canny Kent tuner who was rarely seen without his trilby hat and a pipe parked in the corner of his mouth, and his bespectacled rider whose studious appearance was the antithesis of a stereotype superstar racer.

“The 500cc Arter G50 had a similar Reynolds frame to the Surtees 7R, and I immediately got on with that, too.” said Peter. “I’m ashamed to say I really didn’t care for the standard Matchless G50 frame which my father had developed – I much preferred the Reynolds-framed bikes.”

“So I spent 1966 getting to know them and all their little foibles, but gradually I was getting faster and faster on them, and after winning the North West 200 and finishing sixth in the Senior TT, I wound up second in the 500cc Italian GP at Monza. That was my first 500cc rostrum, although I’d already finished second to Giacomo [Agostini] in the Junior TT on the Surtees 7R, my first of seven second places in the Isle of Man.”

“So for 1967 Tom and I decided to give it all we’d got in going for GP glory, even if we were up against Mike [Hailwood] on the Honda four and Giacomo on the MV three with our humble British single. So that year the German GP at Hockenheim was the first round, and Mike packed up, Giacomo won, and I was second – the fastest loser, you know, gallant single-cylinder privateer, all that nonsense. So then it was the TT, but this time Giacomo packed up and Mike won it – but I was best of the rest again, and now I was leading the 500cc World Championship!”

The Arter G50 was an essential part to his early career success despite not being a big fan of the frame.

The next race was at Assen, where Hailwood and Agostini came first and second, but Peter Williams was third, so still led the World Championship on the Arter G50 after three rounds. But at the Belgian GP next weekend he slid off at La Source, and then had a very big crash in the rain at the Sachsenring on the 350cc Arter 7R, severely injuring an ankle.

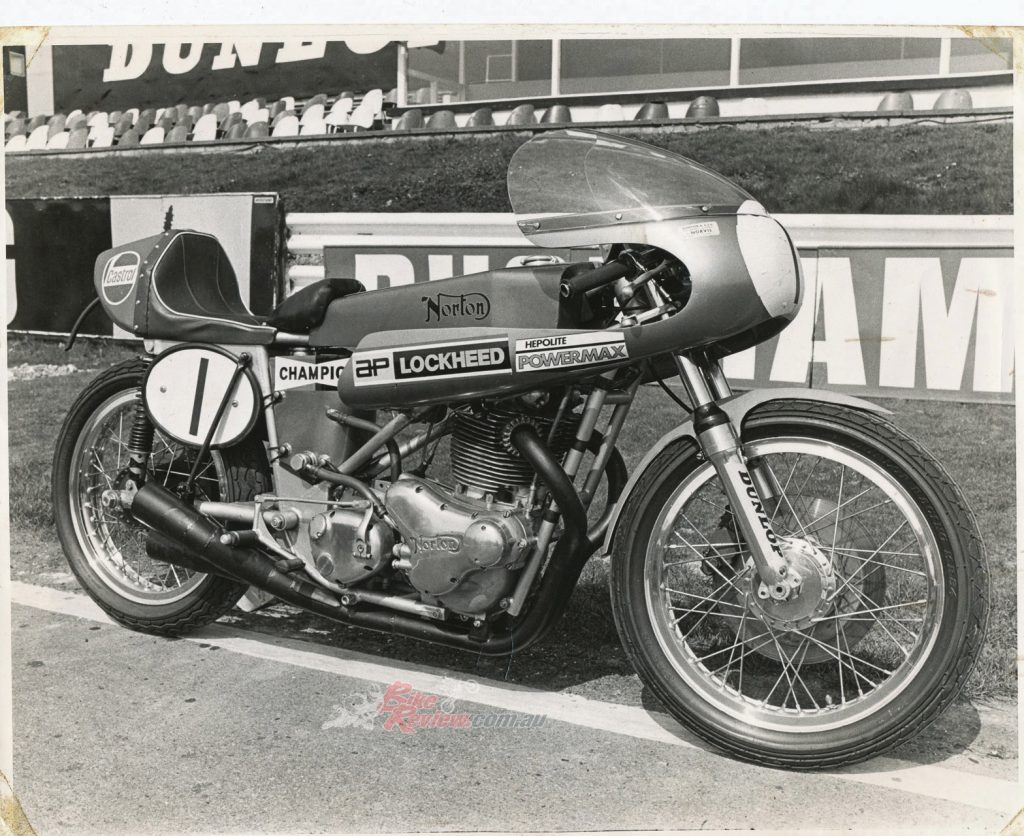

Though Peter eventually recovered from that OK, and wound up fourth in the 1967 500cc World Championship, he didn’t race again that year, but used his recuperation time to firstly design some disc brakes mounted on repurposed wire wheels, and then a set of modern-type cast magnesium wheels. Williams was always at the forefront of new technology, and besides disc brakes, tubeless race tyres, six-spoke cast wheels and wind tunnel developed bodywork, also pioneered the use of a full-face helmet, all now commonplace features in motorcycling today.

Despite Peter’s injuries, his friend and rival Mike Hailwood had arranged for him to race for Honda in 1968 as his teammate – but instead the Japanese factory withdrew from racing, leaving Williams to resume racing Tom Arter’s slower but sweet-handling AJS and Matchless singles, after rejecting a rival offer from Read-Weslake to race their new all-British 500GP twin.

Very short of cash after spending all his savings while off work due to his injuries, he joined the Norton Villiers Drawing Office at the former AMC Plumstead factory – AMC had collapsed in 1966, and the remains acquired by industrialist Dennis Poore’s Manganese Bronze concern.

Suffering from chronic asthma worsened by the squalid conditions in which he was living on very little money, Peter Williams’ racing career almost stalled, despite finishing seventh on a standard Matchless G50 in the Daytona 200 sponsored by a wealthy American fan. Fourth at Assen and fifth at Brno gave him sixth place in the World Championship standings, but a late-season win at Cadwell Park was his only 1968 victory on the Reynolds-framed Arter G50, which he’d now equipped with a front disc brake and pannier fuel tanks to lower the frontal aspect of the bike, thus improving top speed.

But Tom Arter stayed loyal to him, and after receiving experimental asthma treatment at London’s Brompton Hospital, which proved transformative but caused him to miss the entire 1969 TT. Williams effectively recommenced his career where he’d left off before his ’67 crash, by leading the first two laps of the Dutch TT at Assen exactly one week after being discharged from hospital. Agostini inevitably caught and passed him on the fleet MV-3, but second place was a fine comeback ride for the now revitalised Pee Jay.

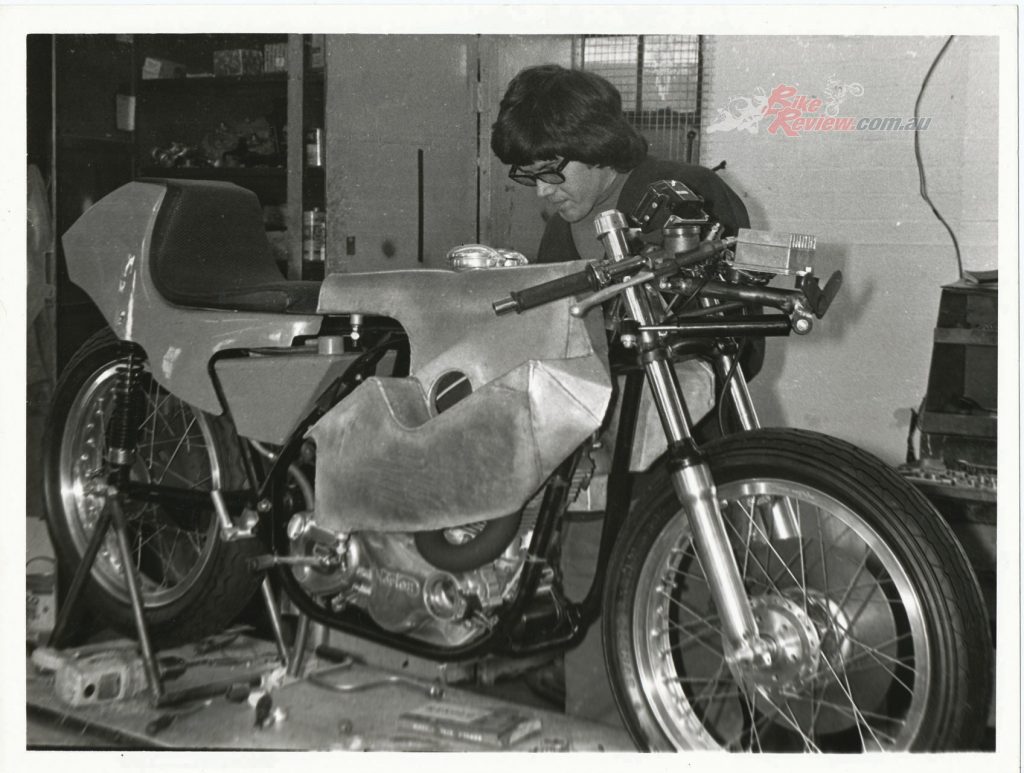

Sadly, though, Williams didn’t have a bike to capitalise on that, because the week after his Assen comeback the Arter G50 he rode there was totalled in a high-speed crash at Spa by Jack Findlay, to whom it had been lent for the Belgian GP. But this was a blessing in disguise, for it obliged Arter and Williams to complete the assembly of a brand-new bike with a lighter, slimmer frame made from narrower-gauge tubing by F1 chassis constructors Grand Prix Metalcraft.

After a stack left the. G50 totalled, they went work revising the whole bike. Ending up with the famous Wagon wheels.

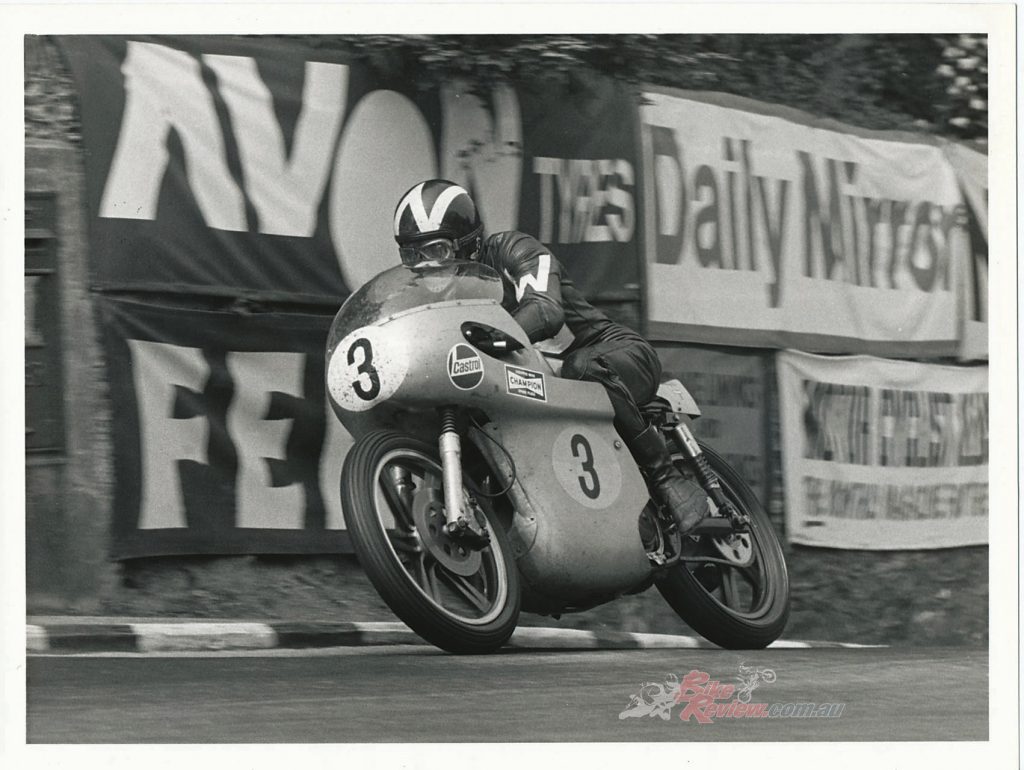

Fitted with cast magnesium wheels, disc brakes front and rear, and ultra-narrow bodywork with slots in the fairing for the ends of the closely-spaced handlebars to rotate – all to reduce frontal area – the new Arter Matchless Mk3 swiftly christened ‘Wagon Wheels’ after a popular biscuit of the day, was truly the first motorcycle of the modern era. Albeit powered by a neo-vintage air-cooled single-cylinder motor, with a Schafleitner six-speed gearbox and chain primary driver. But this coincided with Peter’s job as Norton was being moved to Andover as part of Poore’s corporate reorganisation – and that now included racing.

Norton moving to Andover not only helped his racing career, but his working career too.

“It was late in 1969, and they wanted me to race the production Norton Commando next year, as well as work in the drawing office… So I said – I’ll come to Andover as long as you agree that you’ll definitely go racing, and that I can have a small workshop there at Norton for my Arter bikes. So we went to Andover, and actually set up the Norton Villiers Performance Shop right beside the Thruxton circuit!”

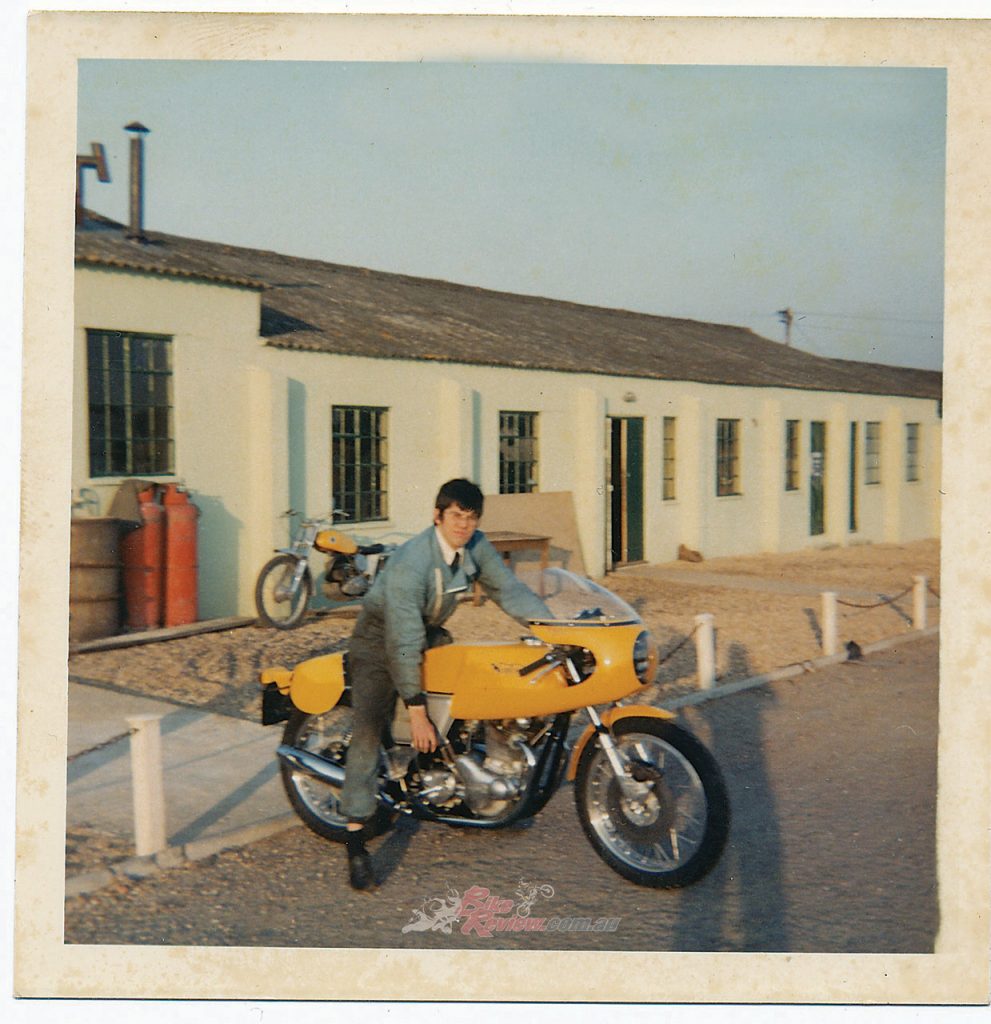

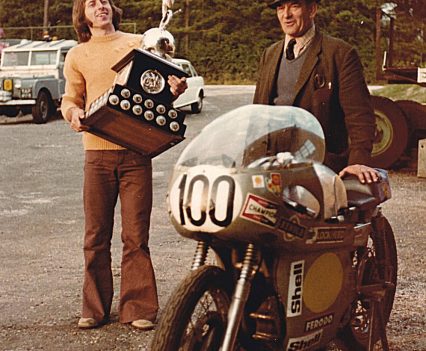

With Norton, Peter Williams duly forged a new career as a successful big-bike rider, winning the 1970 Thruxton 500-miler with Charlie Sanby on the new 750 Commando, as well as many short circuit Production races on a gaudily-painted bike which became known as the ‘Yellow Peril’, and formed the basis of the 1971 customer Norvil Production Racer.

Check out our other throwback stories here…

Sadly, though, he ran out of petrol while leading the massed-start 1970 Production TT in the Isle of Man, spluttering home second yet again after being passed mere yards from the finish line by Malcolm Uphill’s victorious Triumph triple.

He ran out of petrol while leading the massed-start 1970 Production TT in the Isle of Man, spluttering home second.

Forsaking the 500GP series thanks to his new job with Norton, Williams completed Wagon Wheels in the Norton race workshop at Andover. On it, after a season-long battle with Seeley G50-mounted Alan Barnett, Peter won the 1970 British 500cc Championship at the final round at Snetterton, as well as finishing second one more time to Agostini in the Senior TT, and fifth in the Ulster GP.

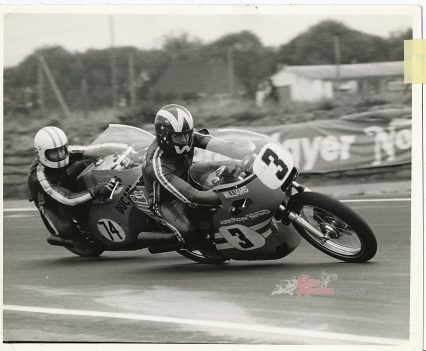

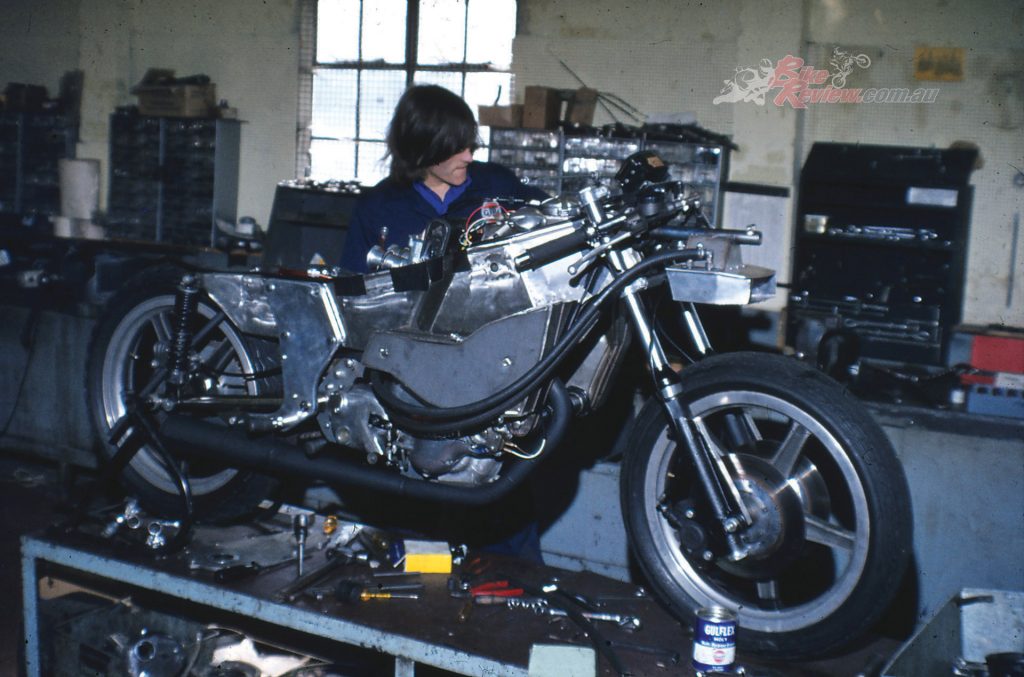

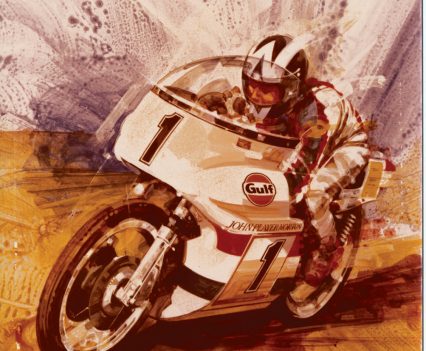

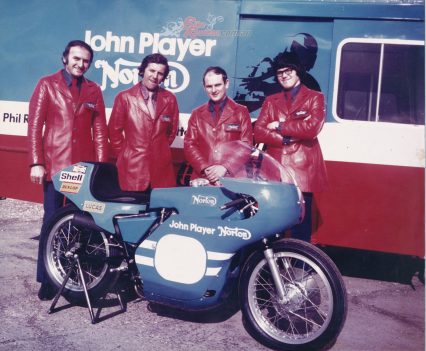

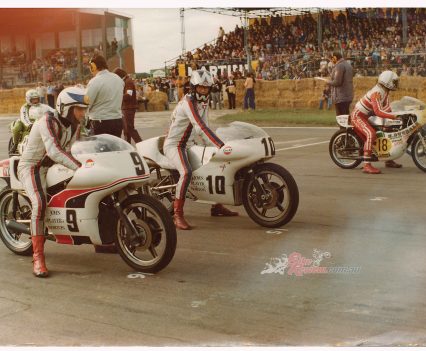

In 1971 Peter constructed a one-off Formula 750 Norton which he raced successfully, thus convincing Poore of the potential of racing as a promotional tool for the Norton marque. So for 1972 the NVPS was entirely given over to development of a team of new Formula 750 bikes. The newly-crowned 250cc World champion Phil Read was recruited to ride alongside Williams, and former factory Suzuki GP rider Frank Perris as team manager.

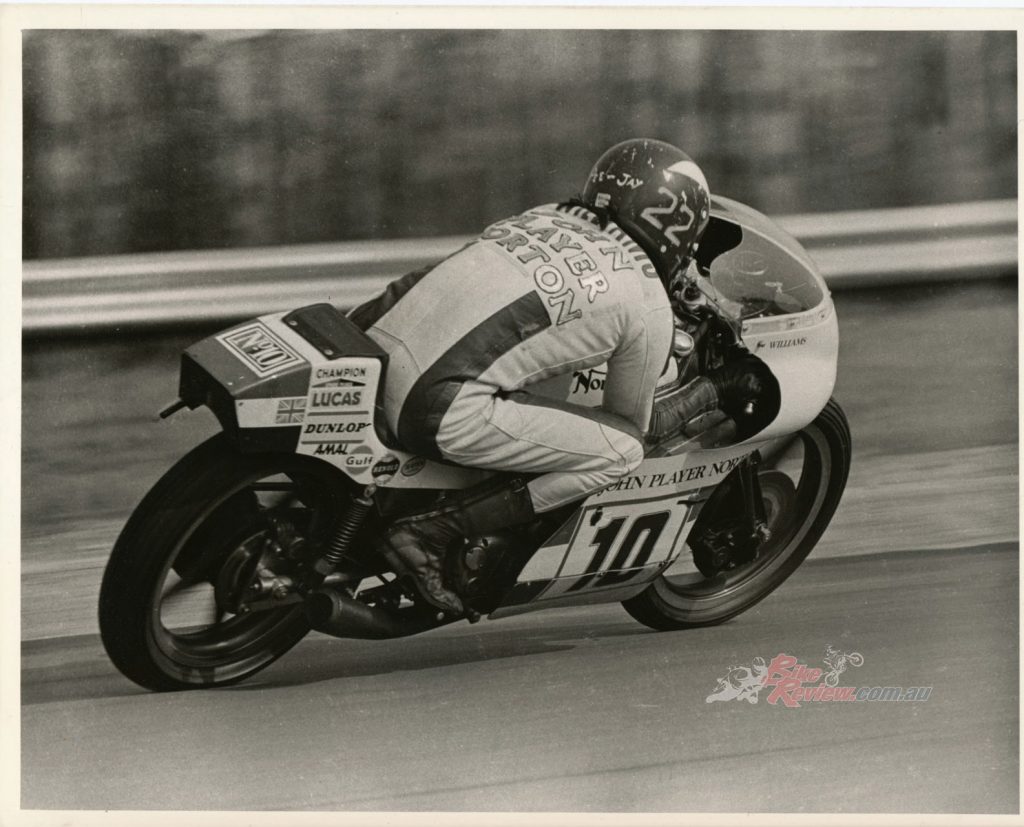

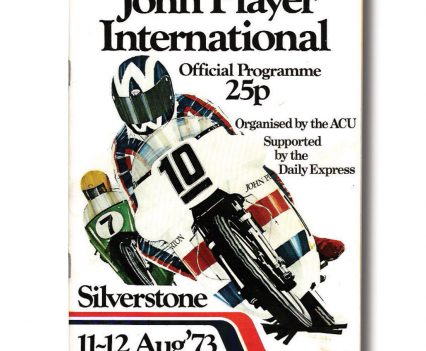

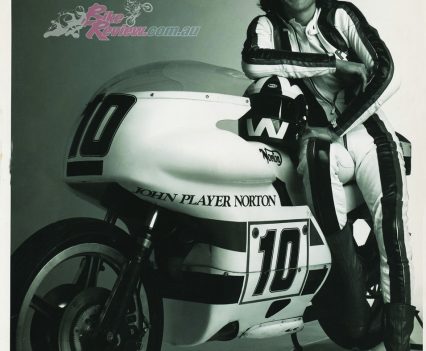

As the final ingredient in a fascinating cocktail of talents, former Formula 1 car racer Poore used his four-wheeled contacts to persuade Imperial Tobacco to sponsor the Norton race effort. This resulted in the formation of the John Player Norton team, the first motorcycle racing team to be fully supported by an outside sponsor, let alone a cigarette one. A fact advertised in race paddocks by the team’s sumptuous 100-mph race transporter, based on a 7-litre American Dodge V8 van, which also doubled as a mobile workshop.

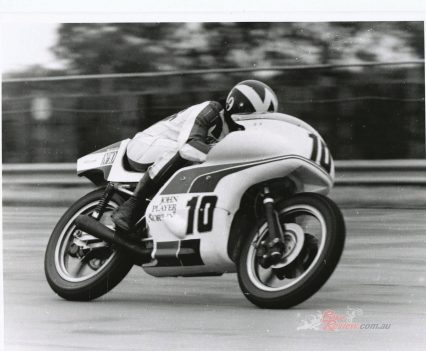

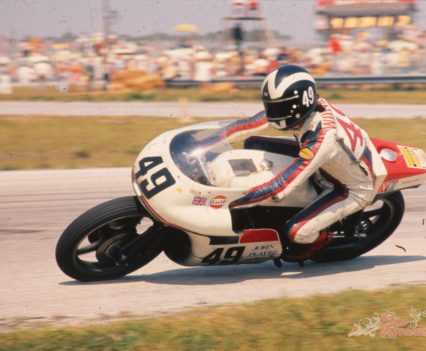

This led to the creation in turn of first the 1972 pannier-tank JPN F750 racer, then a year later the JPN Monocoque – each designed by Williams. After a disappointing Daytona debut caused by fuel vaporisation problems, Williams won three of the six races in the 1973 USA vs UK Transatlantic Challenge, ending up highest overall scorer with four fastest laps to his credit.

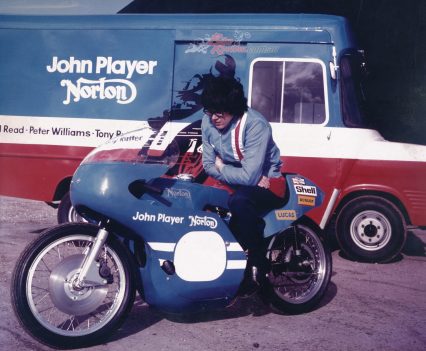

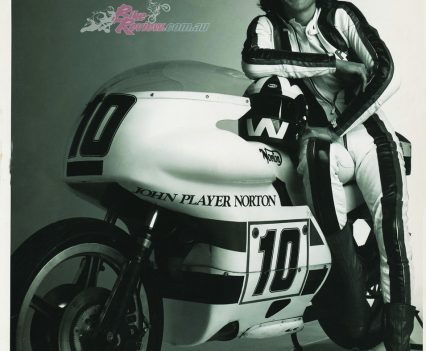

Just before the Monocoque hit the world stage, the Norton was still the iconic Blue with the John Player livery.

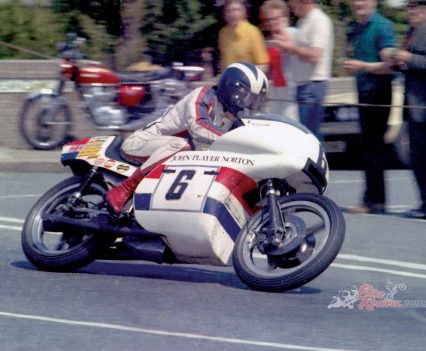

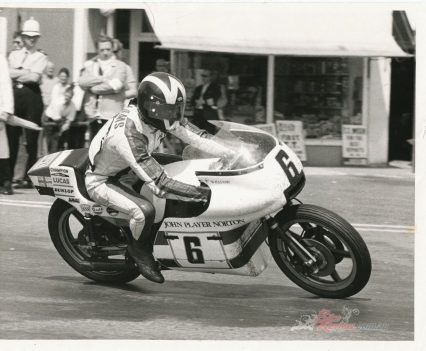

Then winning the 1973 Isle of Man F750 TT on the JPN Monocoque, Peter Williams demonstrated for ever the worth of his unique combination of talents both at the drawing board and on the race track. Expressed at the controls of a truly avantgarde motorcycle he’d designed himself, and which allowed him to achieve the high standards he set himself both as rider, and as engineer.

“I had four parameters for designing the Monocoque,” said Peter, “three of which had been the rationale for the ‘72 pannier-tanked bike – a small frontal area, hence aerodynamic efficiency, a low centre of gravity, and a reduced polar moment by placing the cee of gee in the right place close to the centre of mass, both for easier handling.”

These factors form the basis of GP chassis design today, look at Joan Mir’s MotoGP Suzuki to see that, but 50 years ago Williams and the JPN team were forging a lonely path as the first in the world to adopt such technology in building a race bike.

“The 1972 bike was a stopgap measure to get us out on the race track,” admitted Peter, “so while it incorporated some of these ideas, it was full of compromises, and the engine was too far forward for ideal handling. 1973 was our chance to do it right, to build a really small bike that wrapped the rider around the engine, then filled in the space with a chassis containing the fuel and oil. This also allowed me to obtain the fourth parameter, which the ‘72 bike had hardly addressed – stiffness.”

“Within the parameters of the Isolastic rubber engine mountings to reduce vibration, we created a pretty stiff structure in the Monocoque chassis, and that’s one reason it handled so well. All this reduced the effort needed to change direction, lessened general instability round fast, bumpy turns, and enabled me to flick the bike to and fro, as well as decrease its pitch by reducing the polar moment. People often won’t believe me when I say I could go into a corner on the Monocoque, lay it on its side, get both front and rear wheels sliding, then put the power on early and keep it in a controlled two-wheel drift round any corner faster than Druids at Brands Hatch. It was a really wonderful little bike.”

The aerodynamic capabilities of the Monocoque helped a lot at high speed races such as the Daytona 200.

Spectators at Silverstone in August 1973 to watch that year’s British round of the F750 World Series were treated to seeing Peter Williams demonstrate the truth of that claim, as he grabbed an improbable lead on such a fast circuit against the far more powerful Japanese two-strokes. Visibly attacking top-gear turns like Abbey and Woodcote in masterful two-wheel drifts aboard the underpowered Norton, as he pulled away to what seemed set to be a fairytale victory.

But, cruelly, after he’d equalled Jarno Saannen’s outright circuit lap record, a miscalculation by the JPN team left Peter coasting to a halt one lap from the flag, with yet again a dry fuel tank – a bitter disappointment in what was arguably both bike and rider’s finest race.

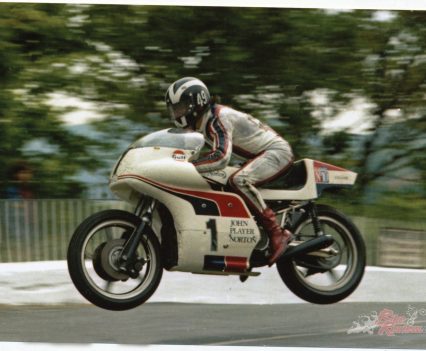

Jealousy saw the end of Peter’s great engineering capabilities, forcing him to ride a slower Sapceframe design

For 1974 Williams, then aged 34, was forced to terminate development of the iconic – and successful – JPN Monocoque, which for reasons which Peter attributed to in-house jealousy and was replaced by a bulkier, slower but more accessible Spaceframe design. It was on one of these that he crashed at Oulton Park in August 1974, when its one-piece fuel tank/seat unit became detached, and Peter Williams was thrown from the bike at high speed, suffering career-ending injuries which resulted in his losing the use of his left arm.

In life after racing, Peter Williams joined Cosworth, working on various projects for the race engine manufacturer he’d already collaborated with at Norton in developing the next-generation Cosworth-designed fuel-injected liquid-cooled twin-cylinder motor for the Challenge F750 racer. These including a prototype desmo cylinder head for Cosworth’s 3-litre DFV V8 Formula 1 engine, and a Supermono racebike, neither of which sadly reached fruition.

Post racing retirement saw Williams continue to work on cars and bikes into his late stages of life.

He was also involved with a similarly abortive project for Lotus Cars, this time the development of a V-twin Superbike with a carbon fibre monocoque frame. In 2015, alongside working as a consultant for major automotive industry players, Williams launched an exact Replica of his TT-winning JPN Monocoque racer for sale, built to original spec via CAD measurements obtained by digitally scanning the original mild-steel prototype bike in the National Motorcycle Museum.

But just four such Replicas were built, costing £65,000($116,000 AUD) each, before he was sadly taken ill and the project foundered. His projected Honda Fireblade-powered carbon monocoque road bike that the JPN Replica project had been intended to raise capital for, thus remained unbuilt. Peter passed away on December 20, 2020 leaving behind his wife Pam and six children, four of them from his two previous marriages.

Peter Williams was a motorcycle visionary who’s often been compared to the late John Britten, in his ability to apply rational thought to moving the goalposts of two-wheeled design, and win races with the result. But Peter’s overall talents outstripped those of the Kiwi designer, for Pee Jay had the confidence and capable riding skills needed to personally take the innovative products of his fertile mind to the limits of their potential, and in doing so to win races against much more powerful opposition.

Peter Williams was a hugely import figure in the development and engineering sector of motorcycle racing.

Indeed, Peter Williams encompassed a unique blend of capabilities that is as rare today, as it was back then. With his design and engineering capabilities living on in motorsport to this day.

![6 R UMAX PowerLook III V1.7 [3]](https://bikereview.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bikereview-Peter-Williams-Silverstone-1972-PW-with-his-two-team-bosses-Tom-Arter-Frank-Perris-426x351.jpg)

March 6, 2021

Thanks for a great trip down memory lane.

Like so many race fans, Peter was a great favourite of mine and I well remember the thrill of him finally achieving his richly deserved TT win.

September 29, 2021

Thanks from the UK for this excellent article. Sadly gone are the days of the engineer-racers like Peter and Rolf Biland, much admired.

September 29, 2021

Peter’s book is a must read .

June 24, 2025

What a excellent tribute to one of the UK’s finest rider/engineer..

Peter Williams will go down in motorcycle racing history as..The very best..always there ..but lady luck wasn’t..Will go down in history with the likes of Hailwood..Ivy..Read..Minter..Ago..