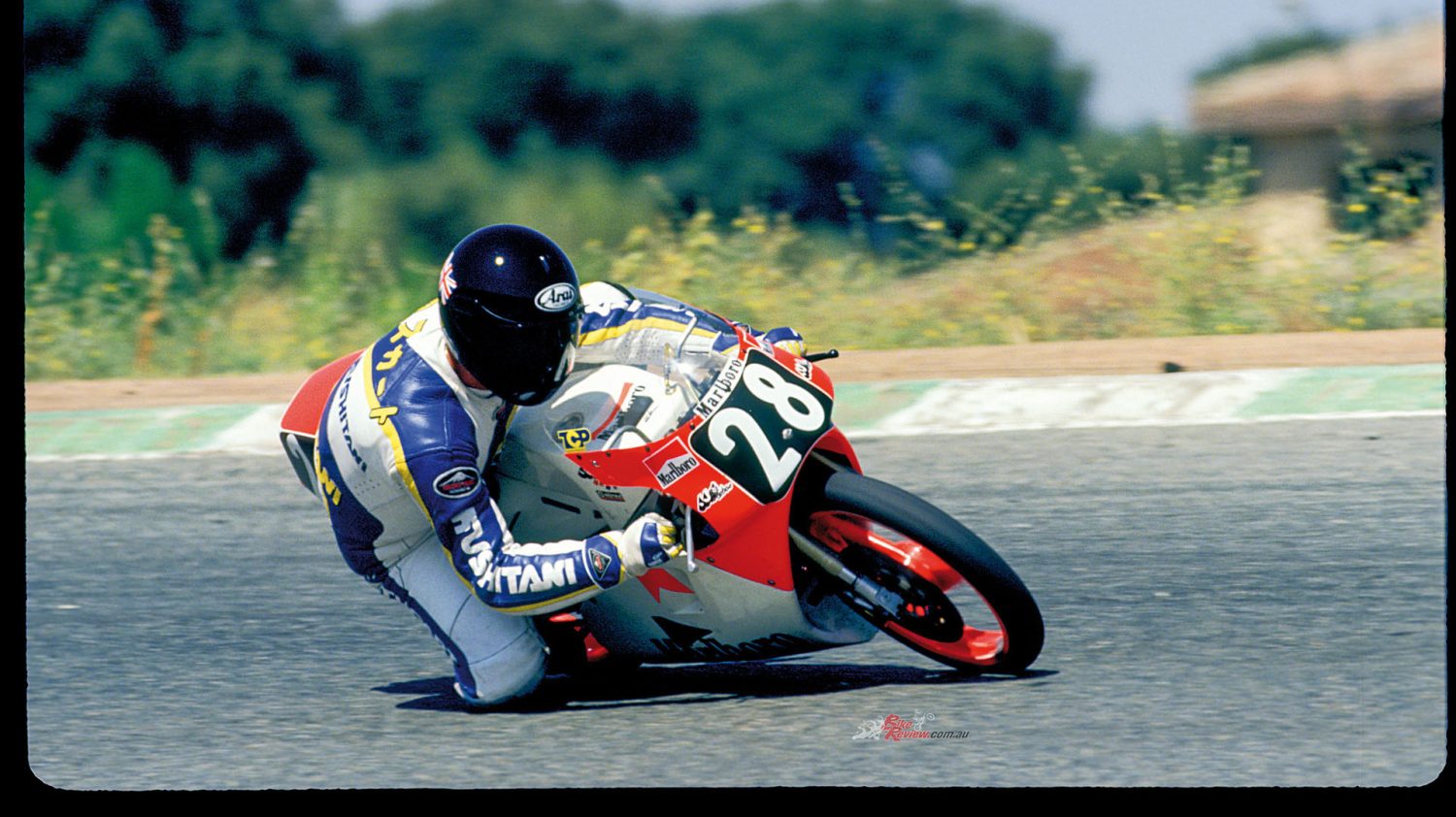

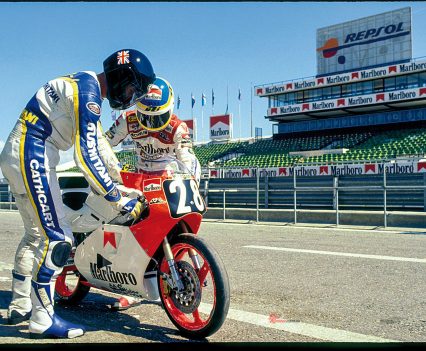

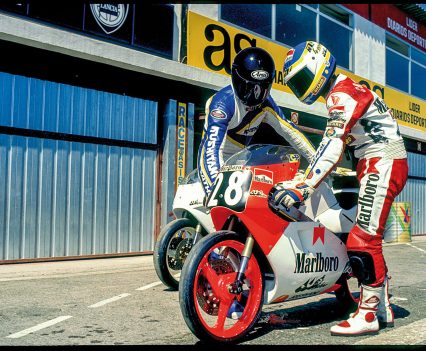

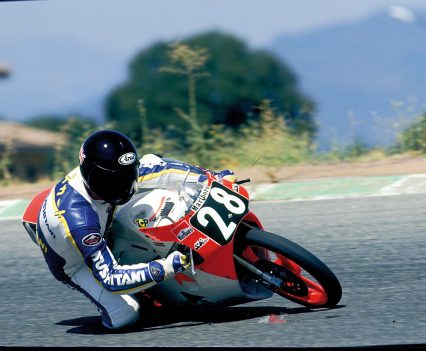

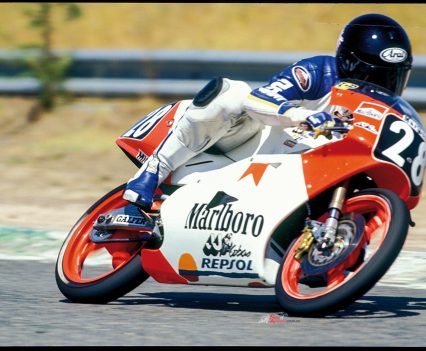

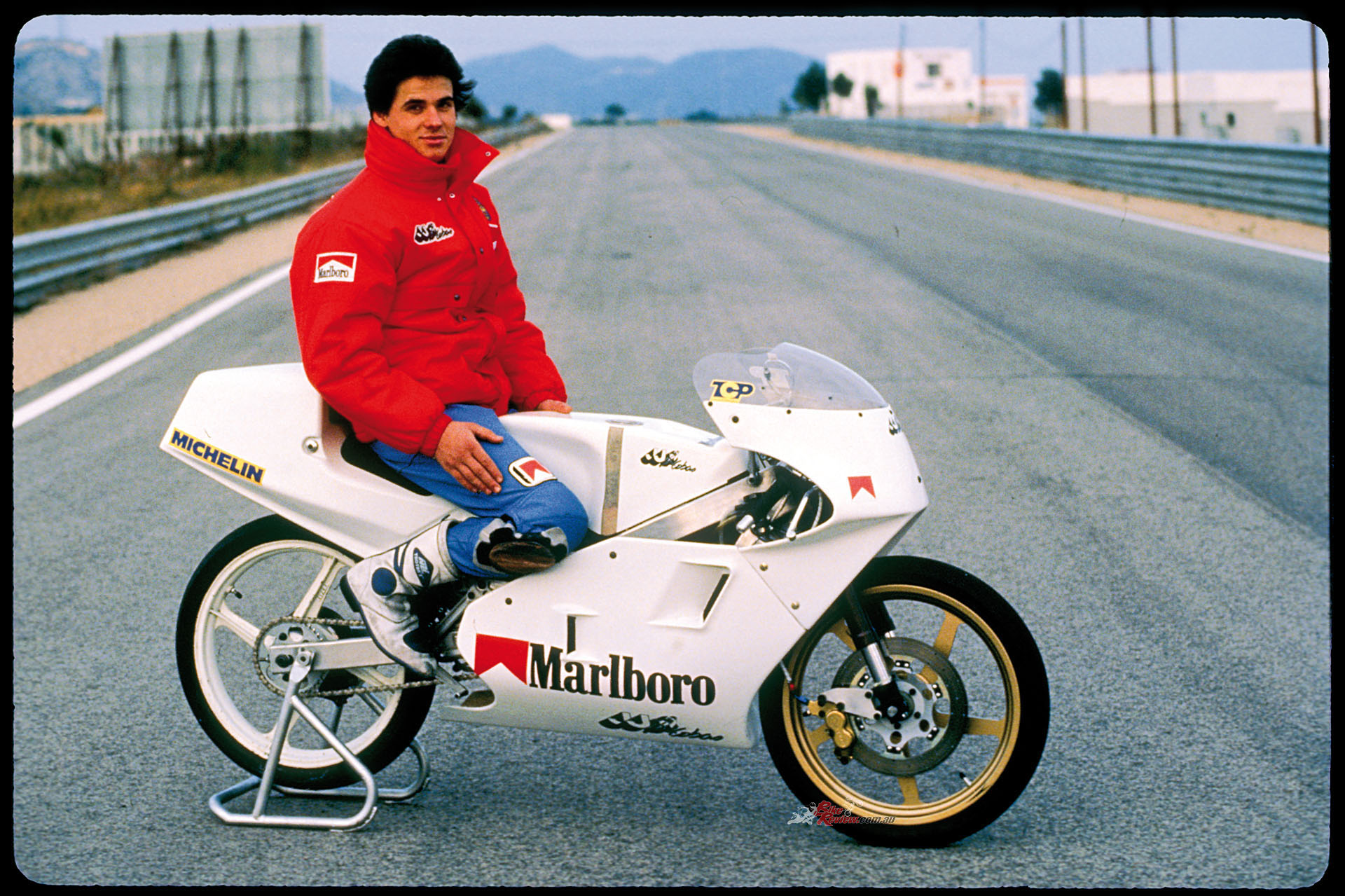

In a 125cc GP season worthy of a Hollywood script, Alex Criville won the title on this amazing JJ-Cobas TB5 125 powered by Rotax. Sir Al got the scoop, of course! Photos: Emilio Jimenez

Having tested Aspar’s 1988 World title-winning rotary-valve Derbi and Gianola’s runner-up reed-valve Honda RS125R in 1988, I figured before stepping aboard it at Jarama that I had a pretty good idea what Crivillé’s 1989 JJ-Cobas World champion would be like to ride.

After all, having a rotary-valve motor like the Derbi fitted in a chassis designed by the leading advocate of forward weight bias and radical steering geometry, with a steep head angle and reduced trail as the recipe for GP success, for sure this would be like the Derbi of comparable architecture, only with some of the harsh edges in power delivery rubbed off thanks to that power valve, but with perhaps an even more extreme riding position than Aspar’s already awkward bala roja 1988 World champion.

Read Alan’s other Throwback Thursday articles here…

Well, how wrong can you be?! Instead, the JJ-Cobas was more like a sort of super-Honda, both in terms of its power delivery and riding position. It felt well-balanced and practically spacious – if you can use that term for such a tiny bike, with just a 1270mm wheelbase – even for someone of my height, and I could actually get my head under the screen down the Jarama pit straight on the JJ-Cobas, a physical impossibility on the Derbi I’d ridden there a year earlier.

Moreover, because the TB5 offered such a neutral stance, it was less tiring to ride hard for any length of time, and especially a 45-minute GP, because you had less body weight on your arms and shoulders – an old gripe of mine about Cobas designs, and certainly a factor in the Derbi when I rode it.

“Conservative steering geometry with a 24° head angle, and 98mm trail”…

In fact, Antonio stated the weight distribution was 54/46% static, but with the rider in place this became nearer 50/50, though with the total mass of rider and machine compacted in such a way as to reduce the polar moment by bringing the centre of mass close to the centre of gravity, so as to offer more stable, predictable handling, aided by conservative steering geometry with a 24° head angle, and 98mm trail.

The result was a bike that was not only extremely effective, as underlined by its title-winning exploits that season, but a whole lot of fun to ride. It felt predictable, smooth and forgiving, with little vibration, a bike that seemed to respond to your thought processes almost before you’d issued them, yet could deliver a light slap on the wrist to stop you exceeding either its or, in my case your own limits.

Alan tested on a warm day, almost doing GP distance with his 20-lap encounter, a bit too much for the tyres on the day, but the excellent chassis dealt with that no problems.

So while the special Michelins fitted gave inviting performance at the start of my 20-lap test session at Jarama – almost GP race distance! – they proved to have too soft a compound for a hot day, and started cutting up quite badly towards the end.

This provoked a number of slides – but in every case the Cobas chassis provided early warning of the loss of grip, even on the fearsome downhill off-camber left hand sweeper into the Bugatti hairpin, which has seen many a better man than me bite the dust over the years when his front tyre let go. The degree of sensitivity offered by the White Power inverted front fork sent a message that the chassis relayed faithfully. All the rider had to do was act on information received so don’t take the feedback!

It was the same story at the rear, where Cobas’ progressive-rate rear suspension had a precision and sense of control completely missing from the RS125R Honda’s less sophisticated cantilever rear end. Alex felt after riding the bike for a couple of laps before I got on board that the rear White Power monoshock was set up too stiff for the bumpy track compared to the much newer and smoother Brno surface, but my extra weight compared to his made all the difference, and it performed superbly round Jarama’s switchback course.

Even at Bugatti, where you roller-coast steeply down into a tight left hairpin, then drive up and out of the turn almost as sharply, the rear suspension worked perfectly, never bottoming out or chattering the wheel when it reached maximum compression. The single 280mm Zanzani front steel disc, gripped by a four-piston Brembo caliper, gave ample braking performance even with my extra weight aboard – so much so that once I started to get brave it was all too easy to lift the back wheel if I grabbed the lever too hard, too late, especially at Bugatti where the downhill approach only made things worse.

Criville first tested the bike at a chilly Calafat in January 1989, concentrating on learning how to set-up gearbox ratios.

Then I recalled Sito Pons’ advice the previous year when I’d ridden his World title-winning Cobas-modified NSR250 Honda at Calafat, and had the same problem. Just like that bike, the JJ-Cobas 125 was fitted with a pro-squat linkage at the rear, so that by not only using the rear 180mm Zanzani alloy brake quite hard instead of regarding it as a cosmetic ornament, but doing so fractionally before I squeezed the front brake lever, I loaded up the rear suspension and minimised forward weight transfer. This helped the WP fork keep working to optimum effect, in turn increasing my turn speed because the suspension was doing its job. And it kept that rear wheel on the ground!

Of course, all that was easy for me to say, and even possible for me to do at about 90% of Alex Crivillé’s title-winning pace. But it was that last 10% that was most vital, or even actually the last 2%, because that’s certainly what enabled Alex to smoke the opposition when it mattered that season. In Sweden, and again in Czecho, he found himself embroiled in eight-man crowd-pleasing no-prisoners battles. Deciding that this was becoming altogether too fraught, the 19-year old veteran simply dropped his lap times by a second, and stretched out a lead over his rivals en route to victory – despite, as was clearly the case in Sweden, having a clear top speed disadvantage.

It is amazing what Antonio Cobas, Alex Criville and the team achieved in such a short period of time.

Instead, the 19-year old rode rings round the opposition in the turns, two-wheel drifting like a speedway star, but with the perfectly set-up suspension of the JJ-Cobas visibly working to maximum effect beneath him. Again, at Jerez, you could see the little Cobas almost floating over the bumps of one of the most demanding circuits in the GP calendar – while his Derbi and Honda mounted rivals struggled to control their leaping, twisting machines.

Anytime someone can lower lap records by a whole two seconds in a single season, as was the case with Crivillé at Jerez compared to Aspar’s 1988 single-cylinder Derbi 125GP mark, you know you’re watching something special happening – especially when engine power had remained almost constant in the meantime…..

Having said that, the JJ-Cobas’s Rotax engine also offered a big increase in rideability compared to the similarly rotary-valve Derbi I’d ridden the year before, rivaling Gianola’s reed-valve Honda in terms of torque – not usually a word used about a 125 single! – and flexibility. Despite the higher altitude compared to Brno, the carburation was perfectly set up at Jarama, a tribute to the long hours spent by Giró on his dyno, and the engine pulled smoothly from 8,000rpm up to just over 13,000 revs in a way that belied its rotary-valve format.

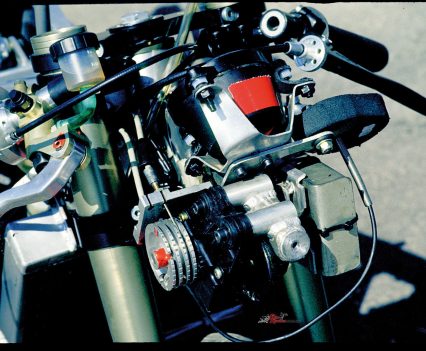

The power valve was obviously responsible for this flexibility, but unlike on 250GP Rotax engines I’d ridden using the same porting and pneumatic exhaust valve, the Cobas didn’t have a step in the powerband around 10,500rpm when the on/off valve came fully open (or closed, depending how you look at it). Instead, there was a completely smooth transition that was presumably due to the more refined operation of the electronically-controlled system.

The advantage of such a punchy motor became evident when I tackled the steep hill behind the pits at Jarama, for example. With the gearing fitted, I had a choice of revving it hard in third, in which case I’d hit the 13,000rpm redline just as I crested the hill under the bridge, and not only had the front wheel lift way off the ground as I did so, but more importantly had to change up at an inconvenient moment while trying to avoid running off the edge of the track, as well as cope with the mini-wheelie!

Better instead to short-shift into fourth at about 10,500, then let the engine’s strong midrange power carry you up the hill before grabbing fifth appreciably sooner for the run up to the blind La Ciega right-hander. The smooth and torquey delivery of the Giró-modified Rotax engine was all-important.

As soon as the title was won in Brno, JJ-Cobas drove straight to Jarama for Sir Al to get the scoop on the bike, particularly good for the National mag, Motociclismo.

Mind you, if I’d been the bike’s regular jockey rather than Alex, I could have opted to change the gearbox’s internal ratios to obtain a set of ratios more suited to my extra weight. The cassette-type cluster was readily accessible via the plate on the right side of the crankcase behind the gearbox sprocket, which unbolted to let it to be removed. Rotax offered a wide choice of ratios even as standard – seven each for first and second gears, four for third, and three each for the top three ratios.

Even this wasn’t enough for the Cobas team, who had the Austrians make them two extra choices for each of the top two and bottom two ratios, as well as an alternative primary drive ratio. With all this potential to become hopelessly confused, it wasn’t surprising Antonio Cobas said he had to spend the first few test sessions after Alex signed up with them teaching him how to set up a gearbox. “Derbi had too much going on to be able to spend the sort of time with someone as young and inexperienced as Alex was, in order to teach him how to do this,” he said.

“The JJ-Cobas’s Rotax engine also offered a big increase in rideability compared to the similarly rotary-valve Derbi I’d ridden the year before”…

“We made 18 gearbox changes alone in our first couple of test sessions, before he began to understand what it was all about, but now Alex has a real capability to choose the right setup for a given circuit, which is crucial in small capacity racing. He also has a great feel for suspension behaviour, even if at the start of the season he wasn’t able to translate this into what needed to be done to remedy a given situation. But he’s a fast learner, and has matured a huge amount this season in every way”…

Call it step one in the learning curve that took the young Spaniard to the 500cc World championship exactly 10 years later with Honda’s NSR500, in 1999!

JJ-Cobas shop in Spain, sadly Antonio Cobas passed away aged just 52, after a serious illness. He was, at the time, the brains behind the Camel Honda MotoGP team in 2004…

1989 JJ-Cobas TB5 125 Specifications

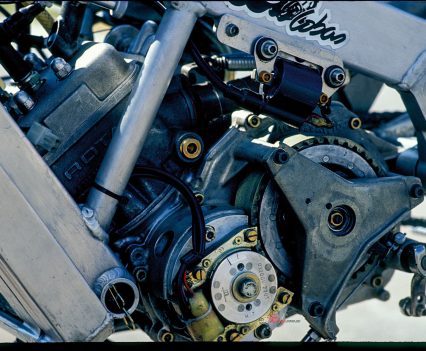

Engine: Water-cooled, rotary-disc-valve single-cylinder pneumatic power-valve two-stroke, 54 x 54.5mm bore x stroke, 124cc, 39mm Dell’Orto flatslide carburettor, Rotax digital CDI, six-speed extractable gearbox, multiplate dry clutch (5 steel/4 fibre).

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar frame, WP 42mm inverted forks, box section alloy swingarm, WP shock, progressive rear link, 26º rake, 98mm trail (95-100mm), 1270mm wheelbase, 54/46% weight distribution without rider, single 280mm Zanzani steel disc with four-piston Brembo caliper, 180mm Zanzani alloy disc with two-piston Brembo caliper, Marchesini cast magnesium wheels 2.15 and 2.75in, 8/56 – 17in Michelin crossply front tyre, 10/59 – 17in Michelin radial rear tyre.

Performance: Power 40.5hp@12,800rpm, Weight 67kg with oil and water, no fuel! 232km/h top speed (Hockenheim)

Owner: Fundaciao Can Costa, Barcelona, Spain