When Honda beat Ducati at their own game with the SP1 in WorldSBK with Colin Edwards at the handlebars, they had no idea what was to come from their Italian rival... Enter the RSV1000-SP... Photos: Kel Edge

Exactly 25 years ago in 2000 came a watershed moment in WorldSBK, Aprilia arrived. Until then it had been a straightforward battle between the Italian V-twin Ducatis and the legions of Japanese fours – but that was the year when WSBK’s grid makeup changed significantly.

First, Honda got tired of going racing under rules which HRC bosses repeatedly claimed were unduly biased towards the Italian V-twins – despite John Kocinski on their RC45 750cc V4 defeating them to win the 1997 WSBK title. So the Japanese firm simply decided to build a better Ducati – minus the desmo cylinder heads, and with a more rational true V-twin layout than the red bikes’ L-twin format. The result was one of the great R&D achievements of the modern era, with the SP-1W (or RC51, as it was confusingly known Stateside), underlining the worth of Honda’s achievement from the very start by winning its first-ever World Superbike race at Kyalami in April 2000, in the hands of Colin Edwards.

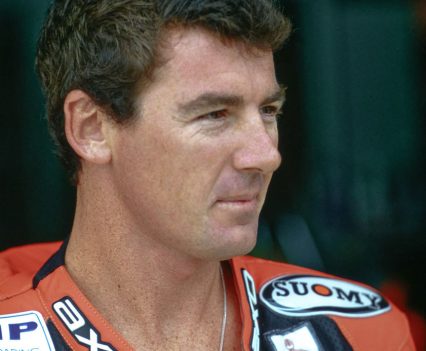

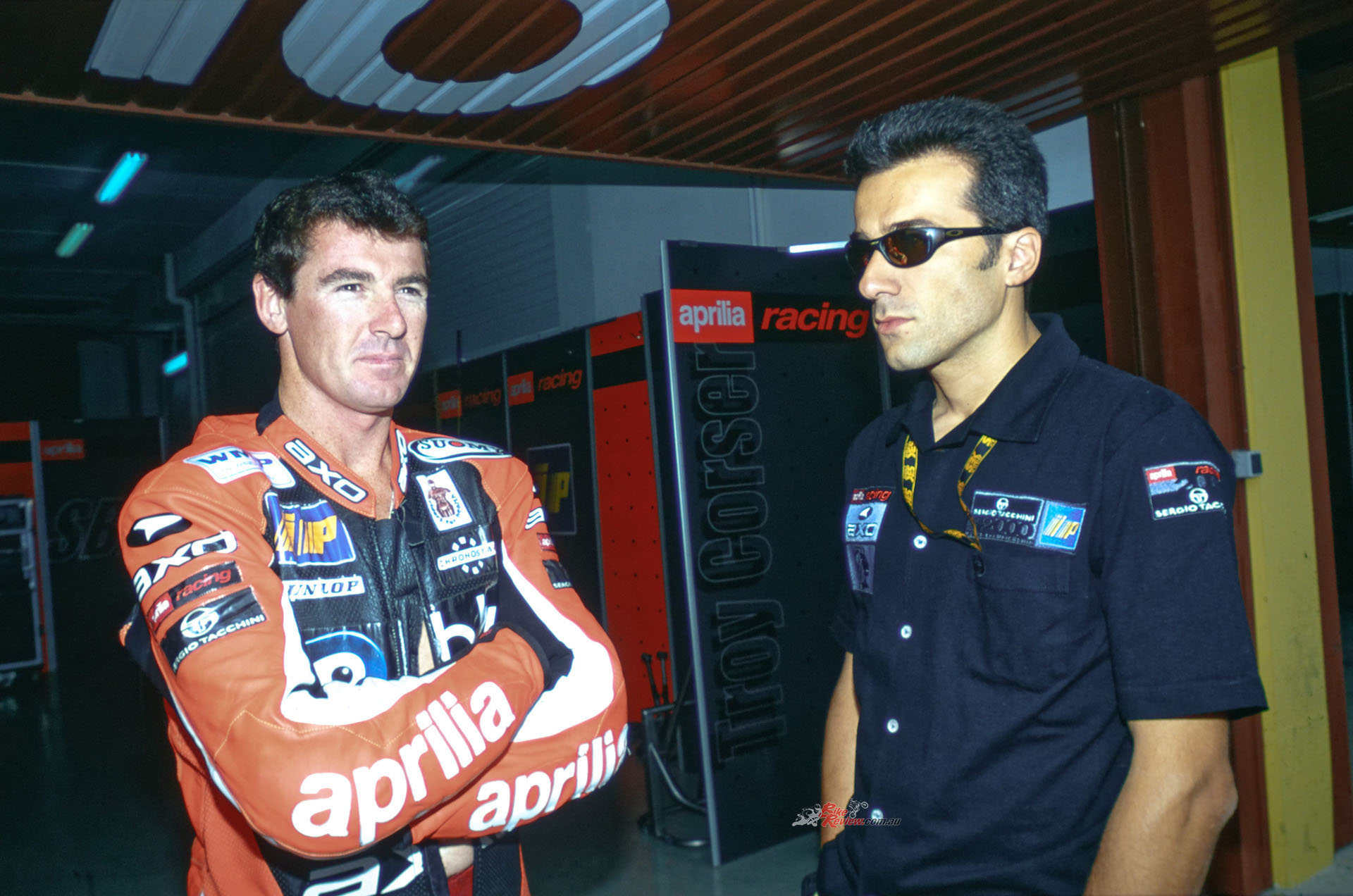

Troy Corser with Aprilia race engineer Giacomo Guidotti in the year 2000. Aprilia would also decisively get the better of Ducati with its brand new RSV1000-SP V-twin…

This led to seven more race victories and a well-earned World Championship crown for the Texas Tornado and the Castrol Honda team, in the Japanese one-litre V-twin’s debut season. Make no mistake, Honda’s feat in ending a decade of Ducati near-dominance of the World Superbike Championship with a brand-new bike built to the same technical specs as the desmo V-twins, was a massive demonstration of HRC’s technical capabilities.

Read our other Throwback Thursday articles here… and Aprilia tests here…

But that was only to be expected, with the new Japanese V-twin heavily tipped to sweep to success after pre-season testing. Plus, it was a Honda – say no more. But what was absolutely not expected at all was that WSBK newcomers Aprilia would also decisively get the better of Ducati with its brand new RSV1000-SP V-twin, which was moreover ridden into third place in the final points table behind Nori Haga’s works Yamaha R7, itself a left field entry, by someone whom the Ducati factory had fired at the end of the previous season under controversial circumstances, 28-year old Aussie Troy Corser.

Troy had won the World Superbike crown for Ducati in 1996, but was controversially ejected from the Italian factory’s SBK squad at the end of 1999.

The unconsidered Corser Aprilia was the true revelation of the Y2K race season, as the product of a firm which had yet to prove it could go racing successfully with anything other than a ring-ding rotary-valve two-stroke GP racer. Moreover, this was billed right at the start of the year as a sort of consolation ride for Corser, who’d won the World Superbike crown for Ducati in 1996, but was controversially ejected from the Italian factory’s SBK squad at the end of 1999 [see interview in features next Thursday] despite finishing equal on points with Edwards’ RC45 Honda as runner-up to teammate Carl Fogarty’s fourth and final World title win.

Anyone who ever thought that Troy Corser was no longer a contender, or who doubted Aprilia’s ability to make four-stroke V-twins that were competitive in World Superbike, had to revise their opinions after the quiet Aussie’s five race wins and four pole positions that season on the ‘other’ Italian Job. Yet after Corser scored what many were ready to write off as a fortunate debut success in changeable track conditions at Phillip Island in April, then cruised to victory in both races at Misano to establish double-up dominance on Ducati’s home track, there were still those prepared to insist that Aprilia were ‘lucky to get it right on the day’.

A lot of the Ducati fans and followers had to eat their words when Troy continued to dominate on the ‘other’ Italian bike…

They had to eat their words after watching Troy make it three wins in three races in Round 8 at Valencia, though – then add another victory next time out at Laguna Seca, after cruising through from sixth place on the first lap to overhaul first race winner Nori Haga’s R7 Yamaha with what looked like embarrassing ease. No wonder every single Aprilia RSV Mille on US dealer floors found a new owner the following week – although it needed another couple of months to replace them thanks to the month-long factory holiday starting the next week! Corser’s third place in the final points table aboard the Aprilia was twice as good as the best Ducati rider could manage – the other Aussie Troy, Bayliss by name, in sixth. Revenge is sweet….!

“Another victory next time out at Laguna Seca… Every single Aprilia RSV Mille on US dealer floors found a new owner the following week”…

Ironically, my chance to sample Troy C’s works Aprilia RSV1000-SP came at a sunny Valencia post-season test session that November, on the very same day I’d already ridden Troy B’s Ducati 996R for 20 laps of the Spanish circuit. That meant comparisons were inevitable between the two Latin V-twin Superbikes – and very different from one another they indeed were. For the Aprilia was one of those deceptive bikes which was quite different to ride than I thought it would be beforehand, and even my first impressions after riding it for a couple of slowish warmup laps to heat the tyres and dial myself in, turned out to be flawed. At that point the session was red-flagged after Ducati’s new WSBK recruit Reubén Xaus obligingly binned his 996R desmoquattro, giving me the chance to return to base and mull over my initial reactions to the bike.

“The 60° Aprilia V-twin engine seemed to need revving harder than its Italian rival – it felt buzzier, and not as torquey”…

Which were – ? Well, the Aprilia Superbike actually seemed lower and more compact that the SP Mille streetbike it was derived from, and wasn’t nearly as wide to sit on as it seemed from looking at it. The rather bulbous-looking fuel tank was actually quite well-shaped and relatively slim, providing a tucked-in but fairly spacious riding position behind the tall screen, which delivered much more aerodynamic protection in a straight line than the only fractionally narrower Ducati’s more abbreviated bodywork, and you also sat a lot lower aboard the Aprilia than on the desmoquattro with its taller 90° L-twin motor.

But the 60° Aprilia V-twin engine seemed to need revving harder than its Italian rival – it felt buzzier, and not as torquey. The polite but blank looks this comment induced in the faces of Troy’s race engineer Fabrizio Guidotti and his pit crew should have given me a clue I was talking tosh – but then the recovery truck trundled past down pit lane carrying the remains of the Xaus Ducati scraped up off the tarmac, and it was time to head out on track once again, to discover the error of my judgement. First impressions are not always the right ones…..

“It paid to keep the Aprilia revving above 8,000 rpm exiting any of Valencia’s tighter turns, vs. 6,000 revs on the Duke”…

Indeed not. My next, much longer session revealed the Aprilia to be arguably even more flexible a racetrack friend than the Ducati, with an even flatter torque curve and almost as wide a spread of power. This invited you to cut down on gearchanging and keep up turn speed, using a higher gear everywhere than you might otherwise have chosen – something the capable chassis was happy to help you do. Still, it was definitely less muscular in terms of lowdown pickup than the Ducati, so it paid to keep the Aprilia revving above 8,000 rpm exiting any of Valencia’s tighter turns, vs. 6,000 revs on the Duke, else you did feel the RSV-SP lag as the engine struggled to get back on the pipe again.

The answer was to use the reassuring handling of the twin-spar alloy frame to max out turn speed, and keep the engine revving as you did so. Do that, and you’d only need to use bottom gear at Valencia once per lap, to get a good drive out of the Turn 2 left-hand hairpin. Everywhere else, I could hold second gear to squirt it between turns, where even on the Ducati I (and Troy Bayliss, too, so it wasn’t just a play-racer problem!) had to keep switching back and forth between first and second. When I did that, the way the Aprilia was geared meant I sometimes ended up using a lot of engine braking from high rpm stopping for the next turn – in which case the slipper clutch did its job really well, with zero chatter from the back wheel as I slowed.

Troy Bayliss and Alan Cathcart riding together at Valencia, a great opportunity to compare the two Italian twins.

The trademark click I’d feel through the lever from the Ducati’s slipper clutch was absent on the Aprilia, though accelerating from a standstill down pit lane in what passed for a practice start, it did graunch a fair bit on take-off, though not as bad as the Ducati, and the take-up was smoother and more controllable as you slipped it to drive off the line – it wasn’t so all-or-nothing in pickup. So that’s how Troy Corser made those great starts from pole position on the grid, hard earned with one of his trademark Superpole flying laps….

“The soft-action revlimiter only fluttered the engine when it cut in at 12,200 rpm, but I only encountered it trying to save myself a couple of gearshifts”…

It wasn’t as if the Aprilia gearchange was so awful you needed to cut back on using it, though – quite the contrary, for the slightly harsh but not unduly sensitive wide-open race-pattern powershifter allowed crisp upward changes as soon as the red shifter light on the dash flashed at 11,800 rpm. The soft-action revlimiter only fluttered the engine when it cut in at 12,200 rpm, but I only encountered it trying to save myself a couple of gearshifts, because I could feel that by then the engine had stopped pulling, and power started to flatten off.

“The Aprilia motor definitely picked up revs faster than the meatier-feeling Ducati, perhaps indicating a reduced flywheel mass”…

By this time, the noticeably greater engine vibration at lower revs compared to the Ducati had begun to smooth out: the 60° engine with one balance shaft removed did tingle quite a bit lower down, and it was this which probably made me think at first the bike was a revver. It had a higher-pitched engine note thanks to the narrower cylinder angle, plus it wasn’t as meaty in terms of midrange torque as the Ducati, which all together made me think I had to use the gearbox to keep it revving higher all the time. Only, I didn’t have to.

“The Aprilia had a completely linear throttle response, with the famous direct connection to the rear tyre that every racer dreams of enjoying”…

Instead, I needed to convince myself to use that one gear higher, rolling back and forth on the throttle as I held the same gear between turns. The Aprilia motor definitely picked up revs faster than the meatier-feeling Ducati, perhaps indicating a reduced flywheel mass and less internal friction – but it still pulled a second-gear wheelie quite happily when I gassed it up hard in the fat part of the power band, and there was ample horsepower and torque to hold the front wheel in the air as I accelerated along the short back straight at Valencia, tapping through the gears up to fourth as the ‘bars waved lazily in my hands.

The Magneti Marelli EFI’s throttle response was precise and predictable, even if Troy Corser said it took a long time to dial out the jerky pickup that gave him 700-800 unwanted revs just as soon as he thought about cracking open the gas even a fraction. No trace of that anymore – the Aprilia had a completely linear throttle response, with the famous direct connection to the rear tyre that every racer dreams of enjoying, and which was surely one reason Troy Corser always looked so smooth out on track as the Crocodile Corser road show cruised to another Superpole or chequered flag.

“A lower rear ride height coupled with a slightly wider fork angle, and more trail on the steering geometry”…

However, arguably THE crucial ingredient in the Aprilia’s Y2K success was the peerless handling of its GP-style twin-spar chassis. This allowed me to carry lots of corner speed through almost any kind of turn – more than back then I could ever recall using at my humble level on another Superbike. A key ingredient in this was the trademark Corser setup, which from my days of racing in a class like Supermono on underpowered bikes where momentum was everything, I’d already come to appreciate from riding his Ducatis in the past, with a lower rear ride height coupled with a slightly wider fork angle, and more trail on the steering geometry.

This delivered a bike that was super-stable in faster turns, at the cost of a little more effort needed to make it steer tighter in slower ones. You needed to muscle it about to make it change direction quickly, like in the fast Valencia chicane leading into the infield hairpin. This balanced geometry may not have been to the taste of barely reformed flat-trackers like Ben Bostrom, who told me he hated riding a Ducati with Corser steering geometry, but it did allow you to carry a high turn speed and use lots of angle – crucial elements in getting a fast lap time on anything other than a point-and-squirt motorcycle, which the Aprilia most definitely was not.

A vital factor in obtaining this was front tyre grip, and here not only the fat, forgiving contact patch of the Aprilia’s 16.5in front Dunlop played a key role, but also the way the more concentrated mass of the compact 60° V-twin motor delivered extra weight to the front wheel, in turn enhancing grip. The Aprilia’s 54/46% frontal weight bias was much more pronounced than any L-twin Ducati could ever be, thanks to the way its crank was located 100mm closer to the front wheel than on the desmoquattro – and this paid off in the way you could crank the Aprilia hard over to maximise turn speed, without worrying too much about pushing the front end exiting any of what on this bike were the many second gear corners at Valencia. The compliant response of the Öhlins fork helped make this possible, effectively ironing out the bumps in the second infield right-hander which so upset Yanagawa’s factory Kawasaki I was also riding that day.

“The Aprilia’s 54/46% frontal weight bias was much more pronounced than any L-twin Ducati could ever be, thanks to the way its crank was located 100mm closer to the front wheel than on the desmoquattro”.

The Aprilia just shrugged them off, same as at the last turn before the Pit Straight, where I’d sweep into the dip in the apex and the front suspension compressed just as I wanted to get on the gas, even after letting off the brakes. With the same latest-spec radial-mount 320mm Brembos as most of the rest of the Superbike grid, the Aprilia had no special edge in this area – except that it was extremely stable under heavy braking, like at the end of the main straight as you backed off three gears while squeezing the brake lever hard for the third-gear Turn One sweeper that followed it. The fact that the Aprilia didn’t move around at all when stopping hard from high speed made it easier for someone who really needed to convince himself he hadn’t gone in too deep, to choose the right line and get round OK. Phew! This could get addictive…..

So no problemo for the Öhlins front end, and none either for the rear shock, once the team had fitted a stiffer spring to stop me having to move my weight forwards down the main straight to prevent the Aprilia wobbling under power. Traction out of turns after I’d dialled up wide-open power was really good: I could feel the rear tyre dig in and drive, as the Aprilia chassis made the most of what the engine delivered, thanks also to the progressive rear link, and the extra grip delivered by the 70mm longer swingarm which the 60° motor’s more compact architecture delivered, compared to the 90° L-twin Ducati. Side grip from the rear 16.5in Dunlop was excellent, again a key factor in getting good drive out of the turn while still cranked over.

“Side grip from the rear 16.5in Dunlop was excellent, again a key factor in getting good drive out of the turn while still cranked over.”

This repaid the momentum I’d obtained by doing so, though you did have to be ready to – ooops! – pick it up hard on the exit to avoid running off the track occasionally, if you went for the high, wide and handsome Corser cornering technique, and didn’t quite judge your exit line correctly! But the balanced handling of the Aprilia frame was really forgiving – it made an average rider feel good, and more importantly, lap fast. Too bad Aprilia had decided to defer the introduction of the small series of hand-built RSV1000-SP Superbike replicas they’d planned to make for sale to privateers. These never got built in the end – pity.

To mark their first year as full-on contenders for Superbike success, Aprilia had restructured their SBK operation for Y2K, giving Troy Corser the backup support every rider dreams of. “They’re so professional in everything they do,” Troy told me. “Compared to some other teams in the Superbike paddock, they work in a much more calm and ordered way. But they still have the Latin passion for racing and thirst for success, and they’re really supportive of my efforts. It’s a great combination, the best of both worlds.”

Aprilia Superbike team boss Giuseppe Bernicchia agreed: “We’re pushing every day in the race team and at the Aprilia factory towards championship success, because Troy Corser is absolutely a real champion, and we owe it to him to support his challenge. He is the dream rider for any team – able to win races through brave and skilful riding, but very clear and precise in his demands for improvement of the bike. I hope we can deliver the World title with the Mille SP Superbike that he undoubtedly deserves.”

Aprilia Superbike team boss Giuseppe Bernicchia agreed: “We’re pushing every day in the race team and at the Aprilia factory towards championship success, because Troy Corser is absolutely a real champion, and we owe it to him to support his challenge. He is the dream rider for any team – able to win races through brave and skilful riding, but very clear and precise in his demands for improvement of the bike. I hope we can deliver the World title with the Mille SP Superbike that he undoubtedly deserves.”

“He is the dream rider for any team – able to win races through brave and skilful riding, but very clear and precise in his demands for improvement of the bike”.

Well, that didn’t happen at the first time of asking, but the following year as far as most paddock insiders were concerned, the 2001 World Superbike season was over almost before it had begun. Aprilia’s dominant display at the opening round at Valencia in March, when Troy Corser scored two start-to-finish wins on the latest Evoluzione version of the RSV1000-SP, seemed to presage a sea-change in WSBK supremacy, in favour of Superbike racing’s third member of the V-twin triumvirate.

But although Corser ran almost as strongly in the next round in South Africa, with two second places at Kyalami that still left him leading the World title chase, that was as good as it got all season long for the Aussie former World champion and Italy’s ‘other’ team. Though Troy’s teammate, the otherwise largely lack-lustre Régis Laconi, scored a contract-time win in the final race of the year at Imola, those two Valencia victories were the only occasions Corser reached the highest step of the rostrum all season long, among the ten visits in all he made there en route to fourth place in the final points table, in a season bedevilled with constant complaints about the quality of manufacture and consistency of the Dunlop tyres he raced with.

So the chance to test Corser’s bike on a sunny winter day at the same Valencia circuit where he scored his double-up victory at the start of the year, was all the more interesting – especially as exactly one year earlier on the same track I’d ridden Troy’s Y2K Aprilia Superbike, and been pretty impressed with what I’d discovered. Would the hard work the Aprilia SBK squad had put into refining the Mille SP racer be apparent?

Well, having been fortunate enough to test ride each of the factory teams’ SBK contenders every year for the previous decade, I was surer than ever that the Aprilia remained the best-handling Superbike I’d yet ridden. That was especially true with Troy Corser’s balanced chassis setup, with a low rear ride height, softish suspension settings, conservative steering geometry and spacious riding stance, all aimed at keeping up turn speed and extracting maximum benefit from the Aprilia’s superlative handling.

“I’ve always liked riding Corser bikes, because his is the way I set my own bikes up”…

I’ve always liked riding Corser bikes, because his is the way I set my own bikes up. But the Aprilia’s compact mass, thanks to the more contained bulk of its 60° V-twin engine compared to its 90° rivals, delivered confident, predictable handling that made you feel at home on the bike very quickly. Plus the fact that the more compact engine could be positioned further forward in the wheelbase than, say, the L-twin Ducati’s longer motor, meant the Aprilia had an ideal 54/46% forward weight bias which helped glue the front Dunlop to the tarmac, so you could take the high, wide ‘n’ handsome route to maxing out turn speed. And it also meant you didn’t get the front wheel shimmying from side to side down the straight, or the handlebars flapping in your hand as you backed into a turn, as with the Bostrom option at the other extreme of the setup envelope. Instead, the Aprilia felt so poised and confidence-inspiring by contrast – mainly an issue of rider setup choice, I know, but still, the RSV chassis had what it took to be the Superbike class benchmark.

“You could surprise yourself how fast you could corner on this balanced, sweet-steering motorcycle.”

It was also very stable and predictable on turn-in under really heavy braking, like for Valencia’s Turn Two hairpin where the reduced weight transfer thanks to Troy’s preferred low rear ride height kept the back wheel only hovering slightly above the ground. This meant the Aprilia went just where I pointed it as I peeled off into the apex, cranking the bike over to maximum lean to keep up turn speed. You could use the slipper clutch to help slow yourself down with the aid of engine braking, all the time remembering that This Is Not a Desmo, so you couldn’t do like Troy Bayliss and buzz the engine to over fourteen grand on the downshifts!

But the Aprilia was great on the brakes – and great in the turns, too, where the ideal weight distribution, the dialled-in Öhlins fork which seemed to deliver a bit more feel from the front tyre in the smaller 42mm diameter used here, and that great 16.5in front Dunlop, all meant you could surprise yourself how fast you could corner on this balanced, sweet-steering motorcycle. It was a very, very satisfying bike to ride hard, especially as the Corser suspension settings proved to be soft but compliant even with my extra body weight. Well, I didn’t have a gym in the basement of my Monte Carlo penthouse, like some people….

But the big improvement in the Aprilia’s performance over the intervening year had come in the engine. Whereas in 2000 this was a bit dozy out of turns, albeit with a nice fat midrange and reasonable top end performance, with a quite conservative but pretty vivid 12,200 rpm revlimiter – now the power curve had been completely redesigned, and the bike made a lot more potent, with a 500 rpm higher cutout.

From being a weakish point, the Aprilia’s acceleration was now transformed into a serious asset out of slower bends. It didn’t wriggle and wind itself up beneath you as you gassed it up out of a turn as a Ducati sometimes did – and there was still an element of communication from bike to rider, a sense of the chassis talking to you as it laid the power down. The Aprilia felt more of a finely honed class act – more F1 Ferrari than the Ducati’s turbocharged Indycar, in their respective responses. Wrong colour, though…..

The Y2K Mille SP’s short-stroke engine also used to have a snatchy pickup from a closed throttle that Troy Corser said it had taken him all season in 2000 to dial out. This had been transformed on the latest bike to a response that was quite comparable to World champion Troy Bayliss’s Ducati 996R I’d been testing exactly one week earlier on the same track, so the memories were quite vivid. Like the Ducati, the Aprilia now had an ultra-clean transition into the powerband, though not as low down as the desmo V-twin. It now drove cleanly from as low as 6,000 rpm, but 7,500 revs was still the power threshold, and it wasn’t quite as muscular low down as the Ducati, plus there was a little ever present vibration, mainly through the footrests.

It wasn’t ever bad enough to become an issue, or even noticeable once the adrenalin started flowing, only on your slowdown lap after race engineer Giacomo Guidotti had waved the chequered flag at you. But then as the 60° engine picked up revs to the higher-pitched music of its Termignoni exhausts, it started to accelerate notably faster than the desmoquattro from 9,000 revs to just under 11,000 rpm. By now the two bikes felt equal in performance, and the fact that the Aprilia was supposedly faster on top end on a fast track may have been down to its undoubtedly superior aerodynamics – it really didn’t feel any bulkier or wider than the Ducati to ride, but you definitely got better protection from the bodywork, and especially from that nicely-shaped screen which invited you to tuck well down behind it along the Pit straight.

The two bikes – coincidentally sharing the same bore and stroke dimensions for just a single season, before the Ducati went to a 104mm-bore format for 2002 with the 998R – now had almost an equal appetite for revs, though the Aprilia’s engine flattened out a little power-wise after the 12,200 rpm power peak. It was definitely best to change up when the red shifter light in the cockpit flashed at you as the extremely legible analogue tacho (hurray – much easier to read than a digital one!) reached the 12,400 rpm mark, though Troy C said he often shifted up just below 12,000 rpm, to ride the torque curve which peaked around there. The revlimiter was now set at 12,700 rpm, but there was no point using it because of the tightened-up ratios of the Mille SP’s ‘01 gearbox. These didn’t lose you more than 1,000 revs in any gear, and hence kept the engine really chiming away in its peak power zone if you changed up around 12,000 rpm, as Troy Corser usually did.

Even so, the spread of power was now so wide that you could run a higher gear most of the way through the Valencia infield, holding it while you played the throttle back and forth between turns. You could even get away with just using bottom gear twice a lap at Valencia – once for the tight Turn 2 first hairpin, then again for the last turn leading onto the main straight, where it’d pull out of there in second if you used a wide line, but it was better in terms of drive if you held it in tight and kicked it into first for extra punch out of the apex, leading to another 300 rpm more in fifth gear, before you backed off and braked for the second-gear Turn One, just as you flashed under the startline gantry (for 2001 Aprilia geared the bike to use just five gears at Valencia, an illustration of the broader spread of power they’d uncovered).

“I tried riding it both ways, and the flexible but potent nature of the 2001 Aprilia motor definitely made using the higher gear a better option”…

This was important, because the change from bottom to second gear was now very harsh, and asked you to back off the throttle for an instant to be sure of changing gear OK, or even fan the clutch for an instant, as you flat-shifted it dirt-track style. Either way, the wide-open powershifter worked faultlessly in all the upper gearshifts, just not that one. This made using second gear preferable wherever you could, rather than shifting back and forth between the bottom two gears for extra punch, as Troy Bayliss did on his Ducati. I tried riding it both ways, and the flexible but potent nature of the 2001 Aprilia motor definitely made using the higher gear a better option.

This illustrated well how much improved Aprilia’s made-over V-twin motor was over the Y2K version, because it now accelerated better than before, and was more rideable in all Valencia’s many tight turns, thanks to the smoother pickup from a closed throttle. It still didn’t have quite the punch lower down that a Ducati had, and I’d imagine that at a circuit like Assen with all those third and fourth gear banked turns where you needed a motor that had a muscular pull down low, this must have been some disadvantage.

But if anything it was stronger than the desmoquattro in that all-important midrange sweet spot – and it also felt a little more poised, less brutal in its dynamic behaviour under acceleration, than its rival from Bologna. I enjoyed riding it very much – and I was impressed how little gearchanging I needed to do in order to go almost two seconds faster on the 2001 bike than I’d done in identical conditions on the same circuit with the 2000 Aprilia one year previously. It was a flexible friend with a mile-wide powerband spanning well over 6,000 revs, making this such a rewarding bike to ride hard, when combined with that peerless chassis.

Nevertheless, Aprilia would have to wait one whole decade before clinching its long-awaited debut World Superbike title in 2010, courtesy of Max Biaggi and its 65° V4-powered RSV4. But that’s another story!

2000 Aprilia RSV1000-SP WorldSBK Specifications

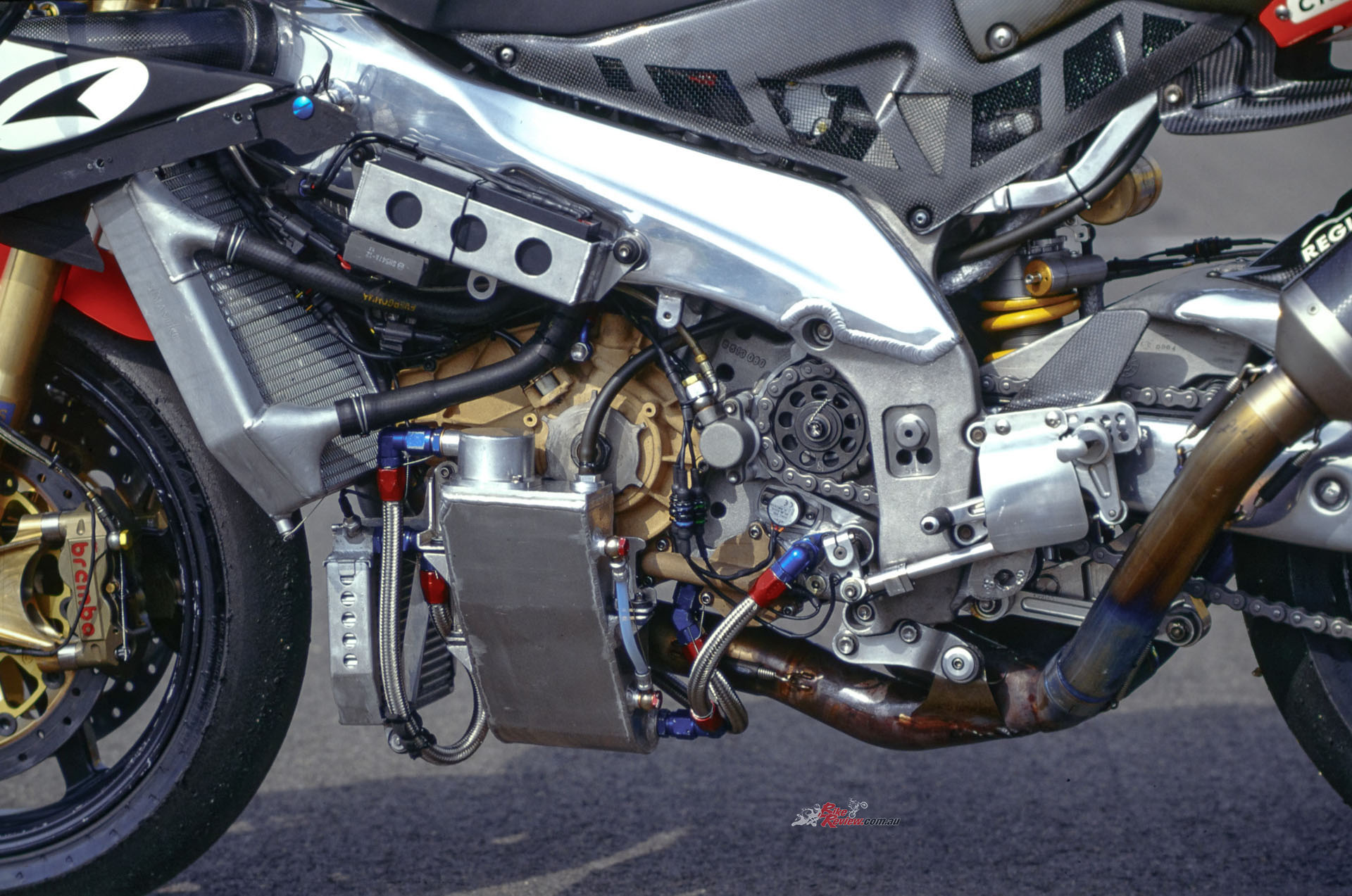

Engine: Liquid-cooled DOHC 60ºC V-twin four-stroke, four-valves per cylinder, chain camshaft drive, single gear driven counterbalancer, 100 x 63.4mm bore x stroke, 12.5:1 compression, 998cc, EFI, Magneti Marelli ECU, twin injectors per cylinder, 60mm throttle-bodies, six-speed gearbox, straight cut primary gear, Nippondenso powershifter, multiplate dry slipper clutch.

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar frame pivoting on engine, braced fabricated alloy swingarm, 42mm Ohlins inverted forks, Ohlins monoshock, rising rate linkages, 23.3 – 25.2º rake, 89 – 101mm trail, 1405mm wheelbase, 54/46% weight bias, 320mm Brembo stainless-steel rotors, four-piston Brembo radially-mounted calipers, 200mm Brembo steel disc, two-piston Brembo caliper, Marchesini cast mgnesium wheels (3.50 and 6.00in x 16.5in), Dunlop KR106 120/75R420 and KR133 195/55/R420.

Performance: 171hp@12,200rpm, 166kg with oil/water, top speed 310km/h, owner: Aprilia Motor SpA.