In 2000, Yamaha dominated, clinching five titles capped by Olivier Jacque’s last-corner 250GP triumph at Phillip Island. Alan rides that bike... Photos: Gold ‘n’ Goose

Exactly 25 years ago in 2000, Yamaha enjoyed an especially stellar race season. In the five road racing categories it contested that year, Yamaha won five out of the 10 available World Championship titles. Sir Al rode the winning YZR250 0WL5 at seasons end. Here it is…

Count them: it won both Riders and Manufacturers crowns in both the 250GP and World Supersport 600 classes, plus the 500GP Manufacturers Championship, as well as second place in the World Superbike Rider’s table, after a controversial penalty inflicted on its rider Noriyuki Haga which Yamaha fought all season long on an official basis to get reversed. Instead, Colin Edwards clinched the WSBK Riders crown for Honda, the company’s only Riders title that year, with the 125GP Manufacturers crown the only other World Championship won by Honda in 2000.

The memories of this bike and era are magic. Here at BikeReview, we remember! In fact, we were there at Phillip Island in 2000…

But Yamaha blitzed the 250GP World series in a 2000 season dominated by their two riders, Japan’s Shinya Nakano and Frenchman Olivier Jacque aboard a bike that was clearly the class of the field – the Chesterfield-sponsored YZR250 V-twin. However, the outcome of their struggle with each other to be crowned World champion was in doubt until the last ten metres of the final lap in the concluding race of the season, in Australia.

It was winner takes all – whoever won the race also took the World Championship, and after Nakano grabbed the lead from the start at Phillip Island, he was closely shadowed for the entire race by his French teammate, as the duo distanced themselves from Honda’s lead rider, Daijiro Katoh.

It was a winner takes all battle at The Island in 2000, teammates Jacques and Nakano both had a shot at the title.

It was a risky business, though – for had the Yamaha duo wiped each other out in vying for the World title, it would have been Katoh – and Honda, not Yamaha – who won it. Nakano led this nail-biting two-wheeled game of poker until the two of them exited the last top gear corner leading onto the Gardner Straight on the final lap, with the chequered flag awaiting them.

Olivier Jacque wafted past his Yamaha teammate to lead across the line by just 0.014sec…

Then, in a brilliantly judged slipstreaming manoeuvre Olivier Jacque wafted past his Yamaha teammate to lead across the line by just 0.014sec, to snatch the World title from him after a season in which the two of them had dominated the standings, with eight victories in the sixteen races (three for Jacque, five for Nakano), eight pole positions, 23 visits to the podium and first and second in the World Championship. Can’t ask for much more, can you?

Indeed, few World titles had yet been won with as much finesse as Olivier Jacque’s aboard the Tech 3 Yamaha YZR250 0WL5 – the factory designation for this unique machine. No wonder team boss Hervé Poncharal sat drained of emotion in the Press Room after the race, when I congratulated him on a mission accomplished in full. “I don’t want to have to go through that again!” he said ruefully. “Winning the title is great, but knowing that the slightest slip could have lost everything meant we were living on the edge. I feel relief as much as exaltation that it all turned out OK.” Well, OK for OJ, anyway – and Yamaha too, of course!

Zero mechanical DNFs all year long on a bike which was apparently easier to work on than the NSR250, with everything more accessible.

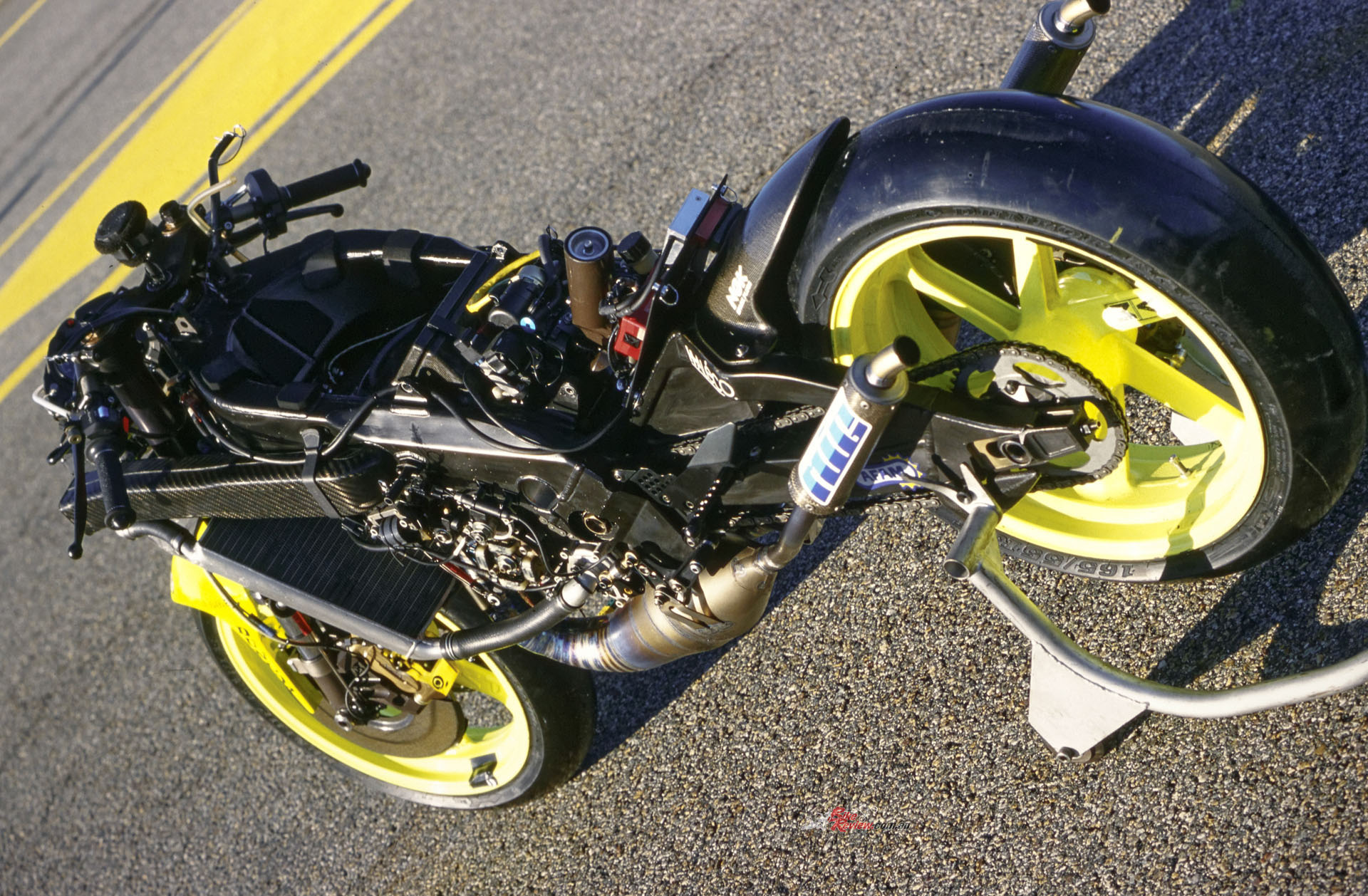

The chance to ride the Chesterfield-sponsored Jacque YZR250 at Jerez a month later, just a couple of weeks after I’d tested Katoh’s third-place NSR250 Honda in Japan, uncovered the secrets of Yamaha’s success. First, though, while Tech 3 mechanic Josian Rustique prepared the bike for me, there was the chance to feast my eyes on the myriad impressive details of what, thanks to its voluptuous and effective streamlining, was surely the most distinctive looking bike on the Grand Prix grids in any class of the Y2K season.

It was a reliable one, too, with zero mechanical DNFs all year long on a bike which was apparently easier to work on than the NSR250, with everything more accessible, and engine setup far less critical – just put gas in, pump up the tyres – and go! Remember, Tech 3 and OJ were in the Honda camp till the 1999 season, so they had the basis for a valid comparison….

The YZR250 could have been Italian, it was so beautifully detailed and distinctively designed. It was a bike which you could gaze at for five minutes, and every ten seconds see something else to admire. Like the twin airboxes required by Honda’s patent of the more rational, and possibly more effective, central one-piece format [Now there’s a surprise – did you know you could patent a design feature in two-wheeler Grand Prix racing? I didn’t], formed by beautiful carbon-fibre mouldings each incorporating an airduct, with one intake low down on the right leading edge of the fairing, the other offset to the left of the nose.

“A bike which you could gaze at for five minutes, and every ten seconds see something else to admire”…

Or the radial mounting of the four-piston Nissin front brake calipers, machine-hewn from solid metallurgical works of art. Or the shrouds over the twin 273mm carbon brakes, fitted to retain heat even in warm weather like the Andalucian test day’s. Or the exquisitely-made large, curved radiator, whose volume gave some idea of the heat which must be dissipated thanks to the power output of ‘over 90 bhp’, according to Yamaha, but reliably understood in fact to be 97 bhp at 12,800 rpm – so not as much as the rival NSR250 Honda, but delivered as part of a more effective overall package.

But there was more. Like the beautifully-welded factory-built titanium exhausts surmounted at one end by French MIG silencers, and at the other by Yamaha’s trademark power-valve system. Or the German-made PVM forged magnesium wheels, which saved a crucial 150gr of unsprung weight at the front, compared to cast magalloy ones, and twice as much at the rear.

Or the Kayaba suspension Tech 3 had used since 1995, even on the factory Hondas they used to run until the previous season, and which the team insisted played a key part in delivering Yamaha the World title, here with a 41mm upside down fork and banana-shaped swingarm operating the KYB rear shock through a progressive rate link.

Or the way that Yamaha had concentrated the mass of the bike so well, yet as you could appreciate by noting how the pivot point of the long R1-type swingarm was located almost in the middle of the 1330mm wheelbase, thus offering enhanced traction, they’d also positioned the 90° single-crank crankcase V-twin engine measuring 54 x 54.5 mm (compared to the 56 x 50.6 mm dimensions of Harada’s 1993 Yamaha 250GP title-winner) quite far forward in order to load up the front wheel – a feature especially appreciated by OJ, whose emphasis on high turn speeds meant he needed a harder front Dunlop tyre than Nakano. Or – well, time to stop stargazing and hop aboard, to find out for myself how OJ done it. And Yamaha, too, of course….

“Rather unexpectedly, despite the narrow, steeply dropped clipons, the riding position was actually relatively spacious”…

But it didn’t end there – because Jacque’s 0WL5 YZR250 Yamaha had what was surely the most distinctive cockpit in GP racing back then, with the narrow, bulbous screen perfectly shaped to deflect air off your helmet, while the broad flanks of the nose of the ‘cowling’ (in fact, for once, the Janglish word is the right one!) took care of protecting your shoulders.

Rather unexpectedly, despite the narrow, steeply dropped clipons, the riding position was actually relatively spacious, even for a 1.80m rider like me who was therefore able to make a pretence of making like OJ and moulding myself to the bike along the short Jerez straights, tucked down behind the all-enveloping streamlining. OJ’s first words after sitting on the Yamaha for the first time back in 1999 were that “I feel like I’m sitting in an armchair!” – and indeed it was a long time since I too had felt so much at home aboard a 250GP racer.

But though less toy-like than the notably smaller, narrower-seeming NSR250 Honda, which seemed in comparison more like a jumped-up 125, the physically bigger Yamaha still felt agile and nimble, despite the bulky bodywork, which didn’t detract from the ease with which you could position the bike in a turn – it steered beautifully, with very little steering damper needed to keep it on the straight and narrow, underlined by the fact that this was unusually mounted on the right side of the cockpit, so would be impossible to adjust while on the move without taking your hand off the throttle!

The engine was slightly less explosive by 250 standards than the Honda, but it felt strong and willing, and above all usable – although to get good drive out of a turn you needed to get it revving above the mark OJ had painted on the tacho at 8,800 rpm, where the power came in strongly – it pulled OK lower down, but not as hard, and the fat part of the powerband was between 11,000-13,000 rpm.

A little more power low down would have been good, but working the foolproof race-pattern gearshift with its perfectly setup wide-open one-way powershifter allowed you to take advantage of what was on offer – and although the shifter light on the dash began flashing at the 13,000 rpm mark, thanks to a very gradual fall-off in power you could hold a gear as high as 13,800 rpm.

“It definitely had stronger midrange power, and thus better drive out of a slower turn, than the Honda.”

It even keep pulling as high as 14,400 rpm if you really insisted, though since the side-loading cassette gearbox was so easily extractable in order to change internal ratios, there should have been no real need to do this. But this extra overrev which Yoda-san’s engineers delivered for the 2000 season was a crucial element in OJ’s title success, said Josian Rustique, because it made the Yamaha easier to ride in the close quarters combat of 250GP racing, allowing you to hold a gear when necessary. But ride the torque curve lower down, and get ready for this 97kg quarter-litre crown jewel to pick up the front wheel on you exiting the Dry Sack hairpin or the final turn at Jerez leading on to the Pit straight – it definitely had stronger midrange power, and thus better drive out of a slower turn, than the Honda.

“Ride the torque curve lower down, and get ready for this 97kg quarter-litre crown jewel to pick up the front wheel”…

However, that wasn’t such a key element in the YZR250’s success as the refined handling which allowed you to keep up what seemed an improbable degree of corner speed in turns, while remaining pretty stable even when you hit a rough patch of tarmac, like exiting the Curva Pons fast sweeper onto the main straight at Jerez, where the Kayaba suspension had to soak up some bumps while you’re cranked hard over while still on the gas, with the rear end compressed and the front light.

“This wasn’t a bike which would have liked being ridden too aggressively – just hard, but with a delicate touch”…

That’s exactly the sort of situation where Nakano used to complain about lack of front end grip on the 1999 bike – but the changes described by Yamaha engineer Ichiroh Yoda had done the trick, and albeit at my more restrained pace compared to OJ’s, the Yamaha’s handling was beyond reproach. It did repay a more polished, precise riding style, though – this wasn’t a bike which would have liked being ridden too aggressively – just hard, but with a delicate touch. Momentum was everything on the Jacque Yamaha, which rewarded the use of wide, sweeping trajectories, so was entirely in keeping with OJ’s liking for high turn speeds.

One strange thing it took me a while to get used to, though, was the soft, very squidgy front brake lever which OJ apparently insisted on. First time I squeezed it accelerating out of the pits, in order to get the carbon discs warmed up in time for the first turn, I thought there must be air in the system – but then I realised it actually works pretty well, because you end up with a more progressive feel and improved sensitivity with the black brakes than if you had a more all-or-nothing hard lever. And, needless to say, on such a small, light bike that was only 2kg over the 250GP minimum weight, the radial monoblock Nissins’ stopping power was simply awesome, and thanks to those shrouds the 273mm carbon discs retained the heat well, so even at the end of the straight response was instant when I squeezed the soggy lever really hard.

“On such a small, light bike that was only 2kg over the 250GP minimum weight, the radial monoblock Nissins’ stopping power was simply awesome”…

When that happened, the Yamaha was pretty stable when stopping hard, despite the weight transfer occasioned by the forward weight bias, which had the back wheel lifting and streetsweeping the tarmac if I didn’t take care to use the rear brake first to counter this transfer. Interestingly, the exact weight distribution was the one piece of data about the bike that was ‘unavailable’ from Moto3, but it presumably was a key factor in making the front tyre stick to the ground so well in turns, allowing you to trail brake deep into the apex of a turn, without worrying too much about washing out the front wheel, or tucking it under. This was a beautifully balanced and neutral-handling package, so whatever ‘corrections’ Yoda-san and his men did to make it handle properly that championship season, worked.

However, it was still rather embarrassing that I managed to lap faster on the YZR250 at Jerez than I did on Carlos Checa’s YZR500 I rode the same day – though I was quicker on Nori Haga’s R7 Superbike than on either of the GP racers, which must say something! But that’s all down to the comparative controllability of the two bikes, for during the many years I tested two-stroke factory 500GP bikes, I’ll happily admit that it was the bike which was in charge, not me – and the secret of my survival was to accept that, and ride it the way it tells you it’s prepared to let you do so.

On a 250, it was the other way round: I’m in charge, not the bike – but the problem was that, because of my Superbike-sized build, I couldn’t usually ride them as hard as they asked to be ridden, for the simple reason I was too big for them. Well, OJ’s 2000 World champion Yamaha was the dream 250 for anyone of normal build – and the fact that I had to be dragged off it at the end of the final day of testing at Jerez underlined how great such a refined and effective package felt to ride, the product of a four-year effort by Yamaha’s engineers in fighting against the odds. Respect.

Sadly, having accomplished its World championship mission, Yamaha officially pulled out of the 250GP class at the end of 2000 to focus on developing its new four-stroke MotoGP contender for 2002 and beyond. This made OJ’s 2000 World crown the last of fourteen 250GP World titles which Yamaha had won since Phil Read earned the first of these in 1964. I’m fortunate to have ridden each different type of bike that the Japanese company used to achieve these crowns, except for the V4 RD05A with which Read and Bill Ivy registered another Yamaha 1-2 in the points table in 1968.

That apart, within the context of their time, Olivier Jacque’s 2000 World champion YZR500 0WL5 was undoubtedly the pick of the crop, and most assuredly one of the finest 250GP motorcycles ever raced up. That’s why it spent the 2000 GP season at the front of the field, where it belonged….

2000 Yamaha TZ250 0WL5 Specifications

Engine: Liquid-cooled single-crank 90-degree V-twin, crankcase reed valve indusction, electronic power-valves, Bore & stroke: 54 x 54.5mm, Displacement: 249cc, Compression: 7.2 – 7.7:1, Fuel delivery: 29mm Keihin flatslides, Exhaust: Yamaha Racing, Gearbox: Cassette-style adjustable ratios, Clutch: Dry, Ignition: Yamaha programmable CDI.

Chassis: Aluminium, twin-spar hand made, Wheelbase: 1330mm, Rake & trail: 22.5º, 82mm

Suspension: Front: Kayaba inverted forks; Rear: Kayaba shock. Brakes: Front: Nissin 273mm carbon rotors, four-piston Nissin radial-mount calipers, 200mm rear Nissin steel rotor, two-piston Nissin caliper. Wheels: Front: 3.75 x 17 PVM Magnesium Rear: 5.25 x 17 PVM Magnesium Tyres: Dunlop KR106 120/60 – 17 and 165/55 – 17 KR108.

Performance: 97kg with oil/water, no fuel, 97hp@12,800rpm, top speed 268km/h (Mugello 2000).

Owner: Yamaha Motor Co., Iwata, Japan.