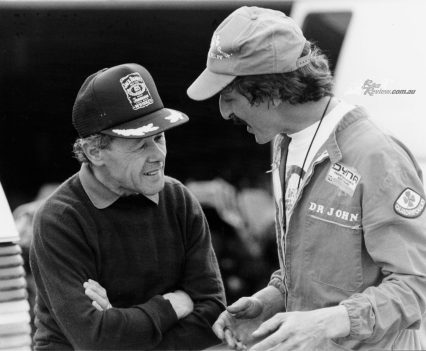

In a significant loss for Italian bike fans everywhere, legendary American Moto Guzzi tuner Dr. John Wittner passed away age 78 on February 15. Alan Cathcart recalls his genius, and takes us for a spin at Loudon on his 8V racer... Photos: Phil Masters

Il Dottore leaving us will be felt not only in the USA, where the bikes he created were raced successfully to three AMA National titles in the 1980s by the team he established to bring Moto Guzzi to the fore again, but also in Italy, his adopted home for more than a decade….

The saga of the former dentist and his various Dr. Johns Guzzi racers reawakened awareness of the historic Italian brand at a time 40 years ago in the late 1980s when its profile was at its all-time lowest ebb, even among dedicated guzzisti around the world. For the story of the Dr. John’s Guzzi racers is a motorcycling fairy tale which, like all such stories, finally resulted in a happy ending, with the owner of Moto Guzzi back then, the mercurial Alejandro de Tomaso, in the unlikely role of a fairy godfather.

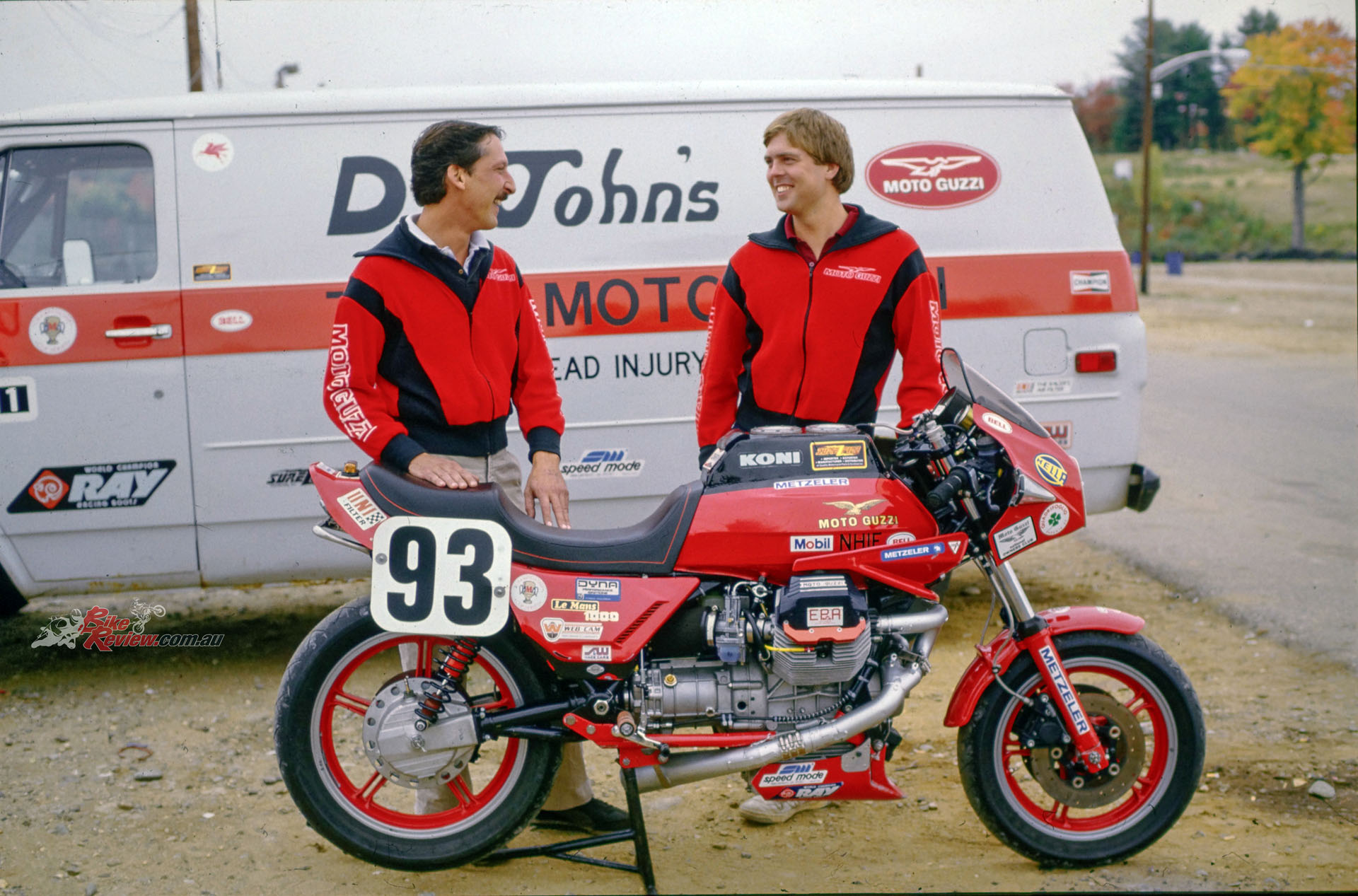

So that’s how the Dr. John’s Guzzi racing team was formed, which in its first year of competition won the 1984 US Endurance Championship’s Middleweight class…

In his spare time from dentistry Wittner had played with tuning Harley-Davidson engines, mainly for road racing around the northeast USA. Then one day, he decided he’d like to buy a Moto Guzzi Le Mans, if for no other reason than he thought it looked neat, and also had a pushrod motor like the Harleys he was familiar with.

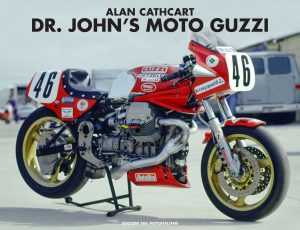

Alan Cathcart has released a book about Dr. John Wittner called Dr. John’s Moto Guzzi which is available now in print or digital format by purchasing online for direct shipment in either English or Italian. For all the info and details, visit the news on the book in our news section here.

Having trained as a mechanical engineer before he took up dentistry, Dr. John also appreciated the Guzzi’s rugged engineering, and traditional looks. “I bought the bike with the sole intent of forming a team of friends to go Endurance road racing with it,” John told me in our final interview just three months before his passing. “I had worked on and ridden a number of Guzzis, and knew they were extraordinarily reliable, the perfect weapon for Endurance competition.”

The Dr. John’s Guzzi team won the overall 13-race US Endurance title outright, from a fleet of Japanese fours.

So that’s how the Dr.John’s Guzzi racing team was formed, which in its first year of competition won the 1984 US Endurance Championship’s Middleweight class, with a perfect 100 per cent finishing record. The following season, in 1985, after Wittner sold his dental practice to concentrate entirely on bike racing, the Dr. John’s Guzzi team won the overall 13-race US Endurance title outright, from a fleet of Japanese fours which were not only sometimes slower but always more thirsty than the pushrod V-twin, a fatal combination in long-distance events. But the year after, Wittner’s fortunes slumped from that high to an all-time low, as he looked further afield for new challenges, reasoning that trying to defend the US Endurance title was the racing equivalent of getting stuck in a rut.

But the lack of suitable races outside the USA where John could race the Moto Guzzi was the key problem, meaning that in 1986 it hardly raced at all, and his money was fast running out. Almost flat broke after two seasons of Endurance racing and two National titles, Wittner staked everything he had on going to camp on the doorstep of Moto Guzzi’s boss Alessandro de Tomaso at his private hotel in Modena – and got lucky, albeit at a cost. “I went with the intent of staying two weeks, but got so involved that I didn’t return home for two months,” said John. “One December morning, I woke up and remembered I’d left my car in the airport parking lot. It cost me a fistful of dollars to extract it……”

De Tomaso recognised in Wittner the man who could help rejuvenate the Moto Guzzi marque’s staid image. John ended up staying for two months as the fairy godfather’s guest in his hotel, and returned to America with a box of business cards identifying him as Moto Guzzi’s ‘Engineering Development Consultant, North America’ – plus enough money to build the Stage 3 Guzzi racer he’d already mapped out before his visit, complete with an all-new box-section spine frame and cantilever swingarm, with floating shaft final drive.

In the hands of Georgia rider Doug Brauneck, the new Dr.Johns Guzzi broke the six-year Ducati/Harley-Davidson domination of US ProTwins racing… the most successful Moto Guzzi racer in the three decades since the factory stopped Grand Prix racing in 1957

The rest is history: in 1987, in the hands of Georgia rider Doug Brauneck, the new Dr. Johns Guzzi broke the six-year Ducati/Harley-Davidson domination of US ProTwins racing, by winning the AMA Championship title to become the most successful Moto Guzzi racer in the three decades since the factory stopped Grand Prix racing in 1957. De Tomaso was so delighted he gave Wittner an even better toy to play with, plus even more $$$ to pay for doing so. Here, dottore, take the prototype otto valvole V-twin engine our engineers have been working on for the past two years, please build your own race bike around it, then help us develop the engine ready for production, by racing it in America in 1988.

Doug Brauneck finished 3rd behind Roger Marshall’s victorious Quantel Cosworth and Stefano Caracchi’s NCR Ducati 851 in its first race at Daytona in March 1988.

The fact that the 8V Dr. Johns Guzzi ridden by Doug Brauneck finished 3rd behind Roger Marshall’s victorious Quantel Cosworth and Stefano Caracchi’s NCR Ducati 851 in its first race at Daytona in March 1988, just adds icing to the cake. That rostrum finish in the world’s premier ProTwins race came without the barely finished bike ever having turned a wheel under its own power until the second day of practice, with the engine still in prototype street form, and tuning restricted to open exhausts, a pair of camshafts from Crane Cams, twin 41.5mm flatslide Mikuni carbs, and nothing else.

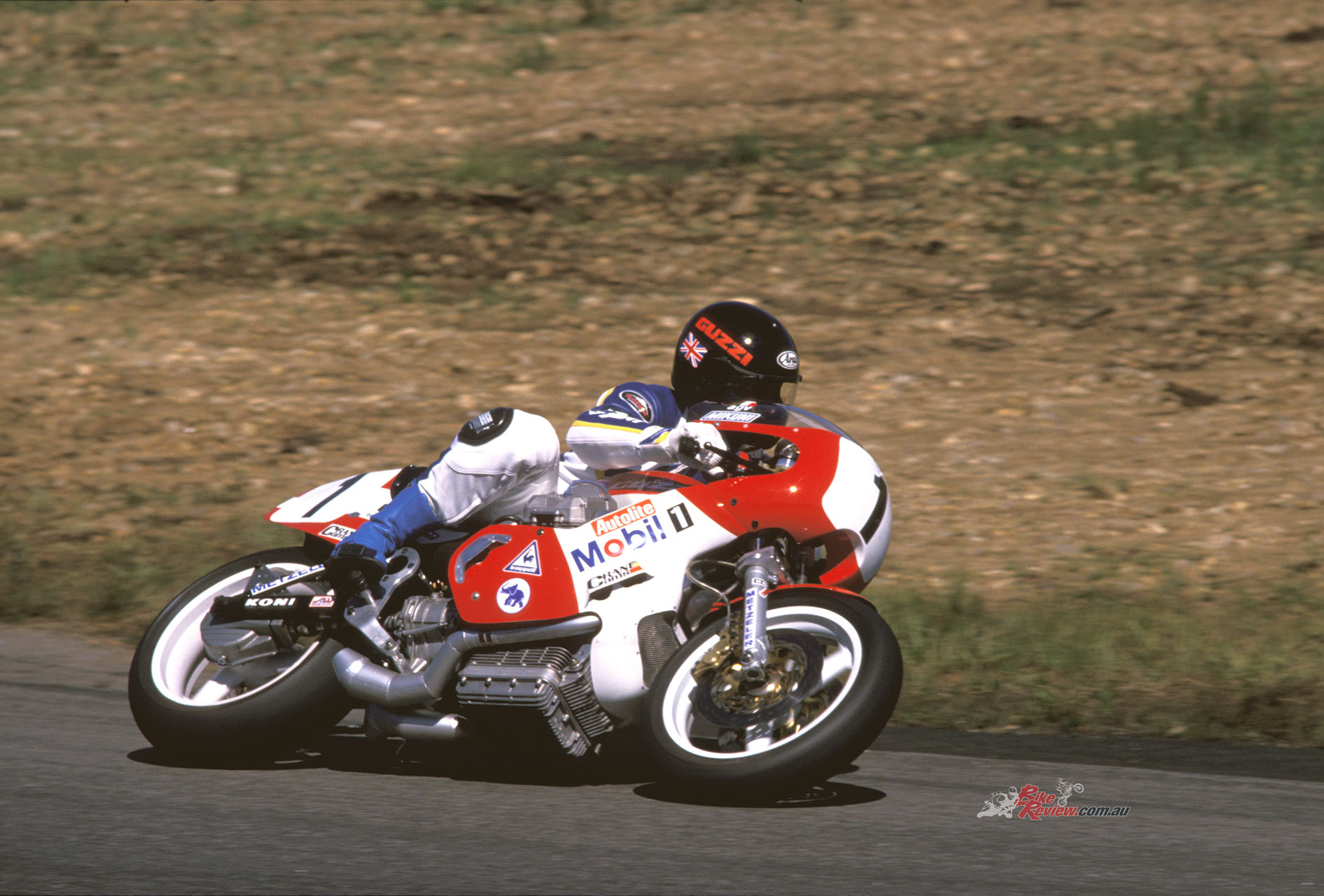

“I was invited to the Loudon track in August 1988 to evaluate the eight-valve, having sampled both the previous 1985 Endurance title-winning and 1987 ProTwins champion two-valve pushrod Guzzis”…

Thereafter, during the rest of that season Wittner and Brauneck ran increasingly strongly to place fifth in the final points table, but inevitably encountered the usual R&D problems you’d expect with a brand new engine – which after all was the point of going racing with it! But overall the 8V bike was faster and better than the previous year’s two-valve title- winner. I was invited to the Loudon track in August 1988 to evaluate the eight-valve, having sampled both the previous 1985 Endurance title-winning and 1987 ProTwins champion two-valve pushrod Dr. Johns Guzzis, and even been enlisted by Wittner to race one at the 1986 Isle of Man TT, only for the bike to get delayed in transit from the USA, and arrive too late for qualifying. This had by now adopted the Daytona name by virtue of its ProTwins rostrum finish first time out, and it was the first journalist test of an engine seemingly destined to form the backbone of Guzzi’s future roadbike range.

Brauneck ran increasingly strongly to place fifth in the final points table during this development season.

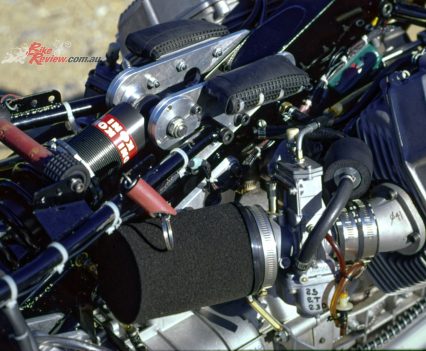

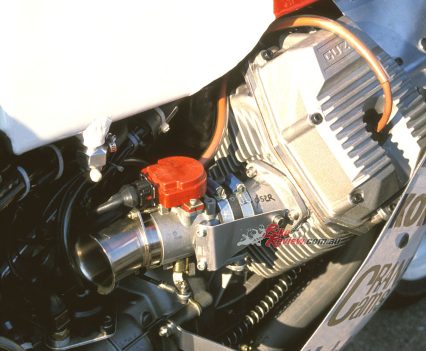

The designer of the air-cooled 90º V-twin 8V Daytona motor was Umberto Todero, a former aide to legendary Guzzi designer Giulio Carcano, as one of the engineers involved in the firm’s title-winning GP team of the 1950s, when they won the World 350GP Championship five years in succession. Todero designed the 8V engine in 1986 as a cost-efficient option for Guzzi’s future, and with full silencing and emissions equipment it produced 92bhp at 7,400rpm in 90 x 78mm 992cc form as it finally reached the marketplace in 1992. Wittner ran it in this guise at Daytona in 1988, making that third place rostrum result all the more impressive, given the calibre of the opposition.

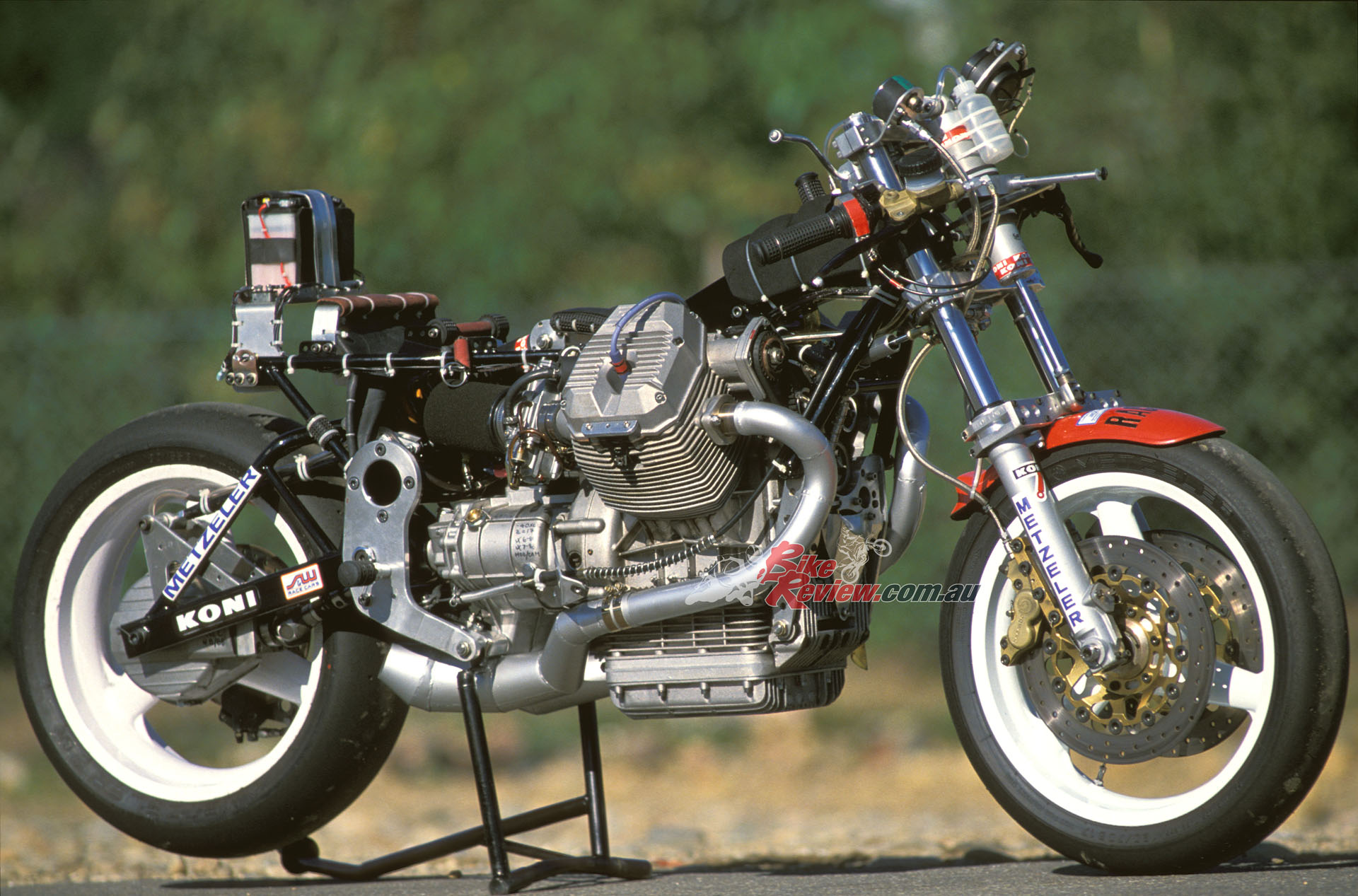

However, in pursuit of the higher revs at which he believed the four-valve heads would come into their own, Wittner short-stroked the engine after Daytona to 95.25 x 70mm for a full 999cc – the same dimensions as his 1987 two-valve Le Mans-derived BoTT title-winner. To achieve this, he fitted a crank from a 750cc V7 Sport, rebalanced for use with the same Carrillo rods and Ross high-silicone three-ring pistons he’d used on the ’87 bike, running in bored-out cylinders fitted with Gilnisil chrome bores, with compression raised to 11.25:1, and larger 41.5mm Mikuni flatslides fitted.

Compared to the previous two-valve motor, the 8V engine was just 40mm wider, thanks mainly to the bulkier valve covers needed to enclose the extra valve gear.

These mods saw crankshaft power raised to 115bhp at 9,300rpm during 1988, but for 1989 the engine was fuel injected with a Magneti Marelli ECU and twin 52mm Weber throttle-bodies. With new Crane cams, Wiseco flat-top pistons, and re-ported cylinder-heads with modified combustion chambers, the 8V engine ultimately delivered 128bhp at the gearbox at 9,500rpm (121bhp at the wheel), good for a top speed of 167mph at Daytona. But Brauneck retired two laps from the end of that ’89 race with a broken cambelt when lying fourth, and reliability had now become an issue. This led to John Wittner retiring from racing at the end of that season, and moving to Italy to work full time in the Moto Guzzi factory on development of the Daytona 1000 street version of his 8V racer.

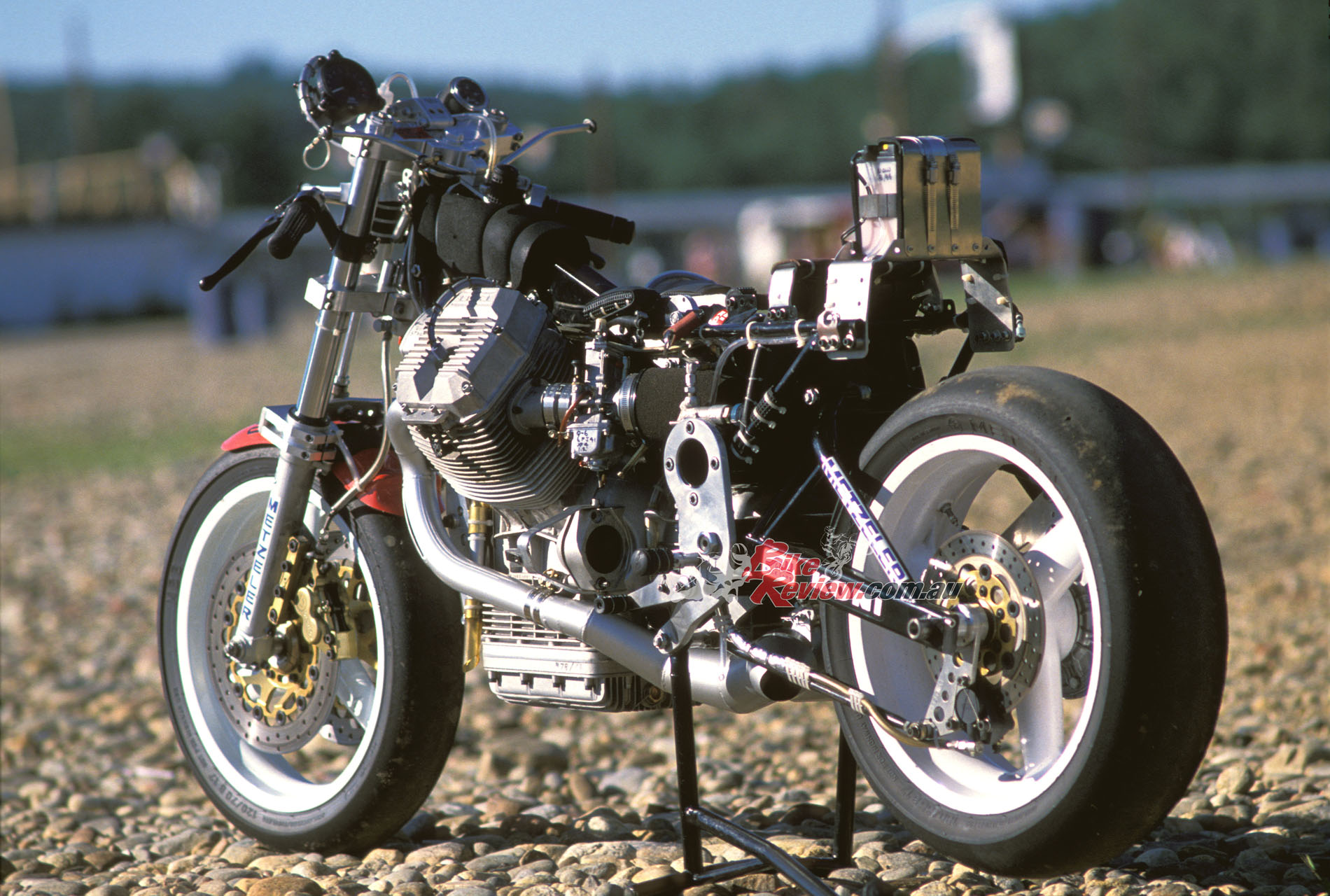

Compared to the previous two-valve motor, the 8V engine was just 40mm wider, thanks mainly to the bulkier valve covers needed to enclose the extra valve gear. Weight-wise, according to Wittner the 8V engine was only 5.5kg/12Ib heavier than the pushrod design, and from my memories of riding the previous title-winning pushrod bike with essentially the same chassis, I’d say that far from noticing any extra top-heaviness, it actually seemed at Loudon to be more agile and easier to lay into a turn or swing from side to side, a key factor on such a slow and twisty track. Frontwards weight bias was a steep 55/45 per cent, good for promoting front wheel grip in turns, with a very compacted mass which aided changing direction.

But I also found when I rode the Dr. John’s 8V Guzzi that the motor was reluctant to rev as high as the 10,000rpm peak John Wittner had been told it was supposedly capable of. Midrange performance was its strong point, with the engine coming strongly alive at 5,200rpm once the megaphone exhausts cleaned out, with a strong build of power as it revved eagerly to around 9,000rpm, and maximum torque available at just 7,300rpm, according to Dr. John. But at just over nine grand it ran out of breath, which in turn meant that the benefits of those eight-valves and reduced inertia and friction obtained by using paired valves with an overhead camshaft design, weren’t yet as great as they surely should have been.

Still, there was already a notable lift in power over the old two-valve pushrod engine, which had delivered 103bhp at the crank – so, around 95bhp at the rear wheel, once transmission losses on the shaft final drive were taken into account, reasoned Wittner – running at 9,800rpm. But remember, the new 8V motor had yielded 115bhp at the crankshaft at 9,300rpm, good enough for a Daytona trap speed of 162mph back in March, since when Dr.John’s continued efforts had definitely improved performance. “We’re only at the beginning of our R&D programme,” said Wittner back then. “For sure there’s a heap of power in there waiting to be unlocked, but till now we’ve been concentrating on street development through racing. I see over 120 bhp at the rear wheel as a reasonable target for our full-race engine.” Time would prove that forecast to be realistic.

“This layout may also have worked OK at Daytona, but at a tight track like Loudon was a definite handicap on the light Dr. John’s bike”…

The close-ratio factory gearbox had a street-pattern gearshift that was way smoother than previous Guzzi gearshifts I’d encountered, but the bottom three gears were closely spaced, with quite a big gap to fourth, and again to fifth. Presumably designed to get the heavier Le Mans production racer up and running out of the chicanes at Moto Guzzi’s local Monza test track, with much higher ratios for the high-speed stretches on the autodromo, this layout may also have worked OK at Daytona, but at a tight track like Loudon was a definite handicap on the light Dr.John’s bike, which even in 8V form scaled only 158kg/347lb with oil, but no fuel.

That’s pretty respectable for a one-litre shaft-drive twin, and it did mean there was less dead weight to haul out of turns, making more evenly spaced gear ratios desirable which would allow you to ride the torque curve and linear build-up of power. There were no plans at that stage for the six-speed gearbox adopted in 2004 on the final evolution of the 8V Guzzi engine on the bored-out 1225cc MGS-01 Corsa – and it’s worth noting the performance of that factory production racer compared to the final version of the 999cc Dr. Johns bike: 128bhp at 9,300rpm at the crankshaft, so around 118bhp at the wheel. Hmm.

“The cantilever rear end soaked up all but the most obscene bumps, even potholes, and had been set up with just the desirable amount of anti-squat to make the most of the radial tyre.”…

The most noticeable characteristic of the 8V engine at Loudon was how quickly and freely it revved, the tacho needle flying round the dial almost as eagerly as a two-stroke, belying the motor’s apparent nature. Conditioned to think of previous Guzzi racers I’d ridden – even, I must admit, Dr.John’s title¬-winning pushrod bikes – as thundering super-tractors with the grunt of a Caterpillar, it came as a surprise to find myself seated aboard this easy-revving, light-feeling bike which, for all its apparent bulk, felt almost delicate in operation. It spun up easily and freely, rather than slugged its way to higher revs.

“The tacho needle flying round the dial almost as eagerly as a two-stroke”…

That applied equally to the chassis. Though with a wheelbase of 1460mm this was not a short bike, it was actually much smaller than you imagined from first glance, with your eye irresistibly drawn to those two meaty cam covers and the hefty, cobby-looking cylinders. Though the chassis employed on the 8V racer was made by Guzzi in Italy, it was a slightly modified version of Wittner’s 1987 BoTT title-winning frame, consisting of a central rectangular-section 2in x 3in (approx. 50 x 75mm) backbone fabricated from 4130 chrome-moly steel, attached at right angles to a 2½in/63.5mm round steel tube located transversely along the swingarm pivot.

This carried twin half-inch/12.7mm thick aluminium plates bolted to it either side, which located the gearbox as well as acting as the pivot for the box-section cantilever monoshock swingarm with fully-adjustable Koni F1 shock pivoting on the frame backbone. The engine was offset a half-inch/12.7mm to the right to allow use of a 5.50in wide cast aluminium 17-¬inch rear wheel specially made for Guzzi by Marvic, shod like its 3.50in wide front partner of the same diameter with Metzeler radial slicks.

Still, I found the way the 8V Guzzi put the power down at Loudon quite impressive, especially considering the rough road surface for a race track of this calibre, hosting an AMA Superbike round each year. The cantilever rear end soaked up all but the most obscene bumps, even potholes, and had been set up with just the desirable amount of anti-squat to make the most of the radial tyre. The compliant, fully-adjustable Koni unit had been well dialled in and delivered responsive feedback without bottoming out in the dip at the bottom of Loudon’s steep descent.

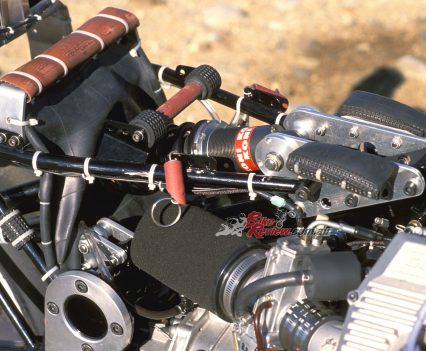

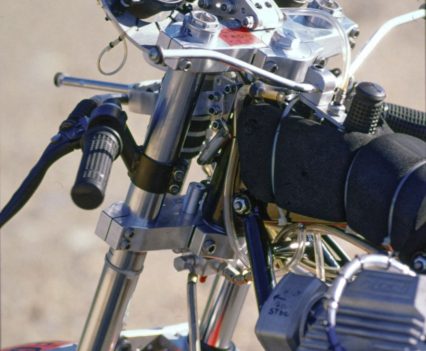

Up front the 41.3mm Marzocchi M1R forks which Wittner had previously employed, set at a 25º head angle via Kosman triple-clamps with 102mm of trail, had now been gutted, leaving only the springs inside the fork tubes, and the sliders merely providing a convenient means of locating the front wheel. The damping had now been transferred to another Koni F1 shock mounted externally in front of the headstock, where it was quickly and easily adjustable for fine tuning, as well as offering the superior response of a fully-adjustable gas-charged unit with sophisticated damping, and increasing the lateral stability of the fork as a whole, according to Wittner.

It was a home-brewed but no less successful version of the similar GCB fork fitted to the Gazzaniga 250 and Paton 500 GP racers of the day, but more importantly also to Marco Lucchinelli’s works Ducati 851 Pantah when it won the 1987 BoTT race at Laguna Seca, which is where John got the idea from as a way of resolving the persistent front wheel chatter that had plagued the bike. I’d complained of that when I rode it at Daytona earlier that same year, and Loudon was a track with lots of places to discover a front end problem if it still existed. At first I did have a problem with the front wheel bottoming out on the many bumps, but a quick damping adjustment by John on the easy-access shock damping soon fixed that, and thereafter the 8V Guzzi handled excellently, especially in the way it handled those bumps on the angle, without being deflected from then line I’d chosen for it, with zero chatter.

What’s more, the 8V Guzzi stopped well, too, thanks to the linked brake system that saw the front lever perform all braking functions front and rear – the foot brake pedal was non-existent! For someone like me who’s never normally used the rear brake on a disc-braked bike, this came as a convenience that took getting used to, even if I was ultimately grateful for it, for it not only increased effective stopping power, but also set the bike up nicely for turns – one reason Mick Doohan invented the thumb brake on his NSR500 Honda not long after! Still, on the Dr.John’s Guzzi you needed to get all your braking done in a straight line, then pitch the bike decisively into the corner under power, rather than trailbrake into the turn. Despite the extreme forward weight bias, the Guzzi didn’t like doing that, as I found when the Metzelers began sliding under hard cornering, but it did accelerate well, powering out of a bend with a glorious thunder from its twin open meggas.

“Despite the extreme forward weight bias, the Guzzi didn’t like doing that, as I found when the Metzelers began sliding under hard cornering”…

Three similar bikes chassis-wise to the Dr. Johns Guzzi, but fitted with pushrod engines based on the 1987 title-winning motor producing just 100bhp as delivered, were built by the Moto Guzzi factory for use in 1989 European ProTwin racing by their various European distributors – one went to Germany, another to France. But Wittner was already looking further ahead to the Daytona 1000 streetbike powered by the 8V engine in a similar chassis to his ProTwins racer, which was launched in November 1989 at the Milan Show, but for various reasons finally entered production only in 1992. By this time, Guzzi had been upstaged by its Ducati compatriot rival which had become a serial winner of the World Superbike Championship with the 888 desmoquattro.

Consequently the Daytona 1000 never received the acclaim it deserved, not even from guzzisti and certainly not from conquest customers. Just 486 examples were built and sold in the model’s debut year in the marketplace in 1992, with numbers declining to 283 bikes in 1993, 155 in 1994, and just 100 motorcycles in 1995. In 1996 the greatly revamped Daytona RS was launched, but Guzzi customers preferred the less costly 1100 Sport pushrod model of near-comparable performance, and so just 113 examples of the RS were made in 1996, and 195 in 1997. The introduction alongside it of the much better-selling and more accessible Centauro powercruiser powered by the same 8V motor ensured the sportbike’s demise, until the advent of the bigger-engined MGS-01 prototype 20 years ago at the 2002 Milan Show turned a new page. It was a sad end to a project that had started so well, with that Victory Lane finish back in 1988 that earned the Dr. Johns Guzzi 8V Daytona its name in its very first race.

“The Daytona 1000 never received the acclaim it deserved, not even from guzzisti and certainly not from conquest customers.”

The Dr. Johns Guzzi 8V racer is now on permanent display in its 1991 final development form in the Moto Guzzi factory museum at Mandello del Lario. John Wittner was always eager to record the contribution of the people he worked with at Moto Guzzi even as the company struggled to survive. “I loved my time with Moto Guzzi and I miss the wonderful people there whom I was so honored and privileged to work with,” he told me. “They were the ones who kept Moto Guzzi alive through the most difficult times, with their hard work and faith in the company. They gave the best they had to give, and then gave some more. My very small story in the scope of the great history of Moto Guzzi would never have happened without them. Too often people associated with a struggling company are maligned as being mediocre, or even worse. For the people at Moto Guzzi back then, nothing could be further from the truth. I salute them.”

Indeed so, but Moto Guzzi fans around the world salute you in your passing, too, John. You will be very much missed by guzzisti everywhere.

Dr. John Wittner’s Moto Guzzi 8V Racer Specifications

Engine: Transverse 90-degree air-cooled V-twin four-stroke with belt¬-driven single overhead camshaft, and four valves per cylinder, 95.25 x 70 mm, 999 cc, compression ratio 11.25: 1, 2 x 41.5mm flat-slide Mikuni carburettors, Dyna S/Raceco electronic CDI, 5-speed gearbox with shaft final drive, Transkontinental single-plate sintered bronze diaphragm clutch with aluminium flywheel

Chassis: Chrome-moly fabricated square-section backbone frame Suspension: Front: Telescopic forks with single centrally-mounted fully-adjustable Koni F1 shock Rear: Box-section steel cantilever monoshock with fully-adjustable Koni F1 shock rake 25 degrees trail 102mm, wheelbase 1460mm, Brakes: Front: 2 x 300mm Brembo floating cast iron discs with four-piston Brembo calipers, interconnected to rear brake at handlebar lever Rear: 1 x 230 mm Brembo floating cast iron disc with two-piston Brembo caliper, operated by handlebar lever on 90/10% linked ratio Tyres/ Wheels: Front: 120/70-17 Metzeler slick on 3.5 inch Marvic cast magnesium wheel Rear: 170/55-17 Metzeler slick on 5.5 inch Marvic cast magnesium wheel

Performance: 115 bhp at 9,300 rpm at the crankshaft, 158kg/347lb with oil, no fuel, with 55/45% distribution, Top speed: 166 mph (Daytona 1989)

Owner: Moto Guzzi SpA, Mandello del Lario, Italy, year of manufacture 1988