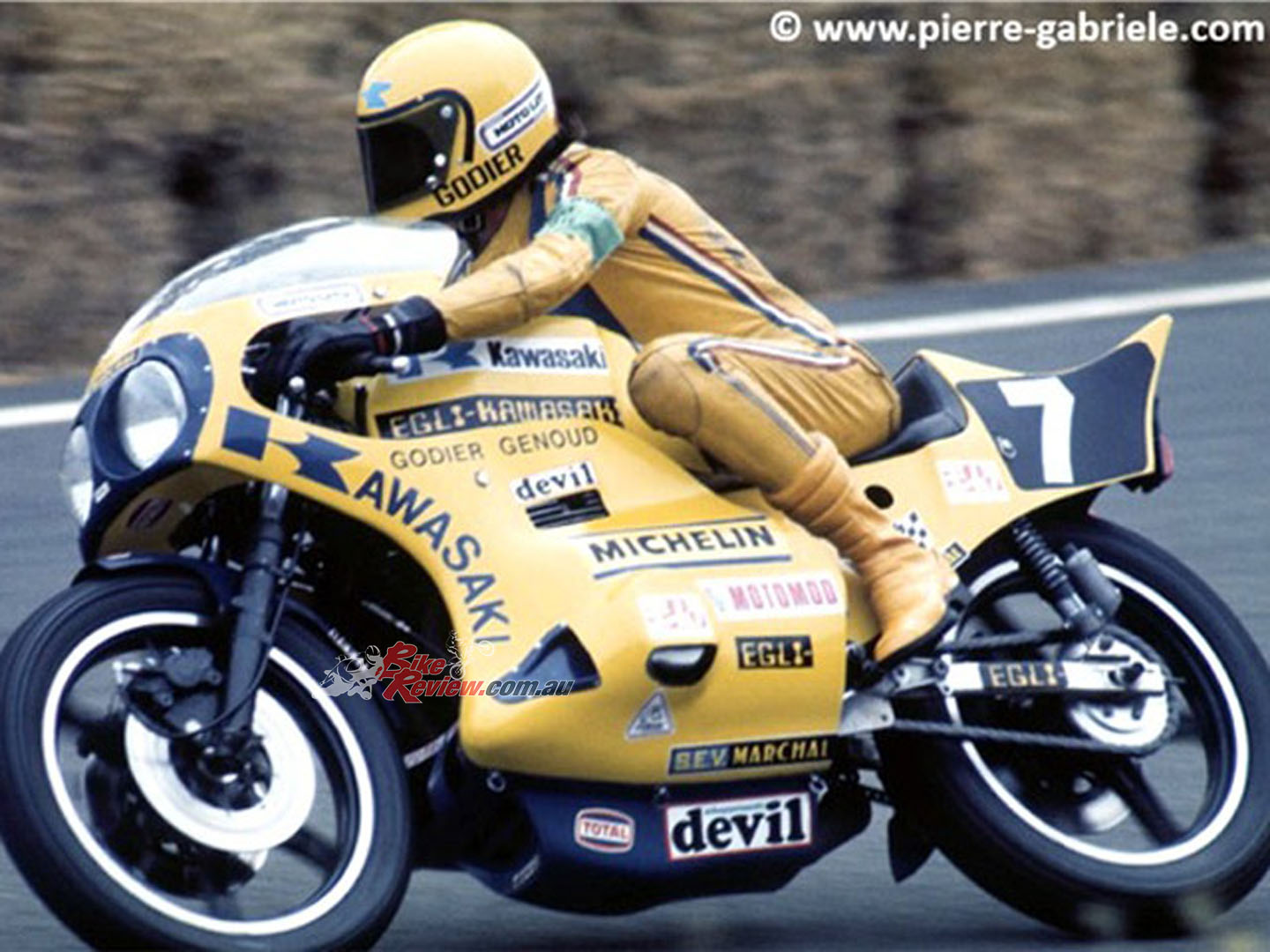

With the 100th-anniversary of the Bol d'Or on September 16-18, we revisit the innovative Godier & Genound Kawasaki 1000 that Cathcart got the chance to ride! Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura

Before it evolved into the long-distance version of Superstock racing that it’s become today, Endurance racing showcased the most innovative motorcycles on the planet. No motorcycle better qualifies for that description than the Godier & Genoud Kawasaki 1000.

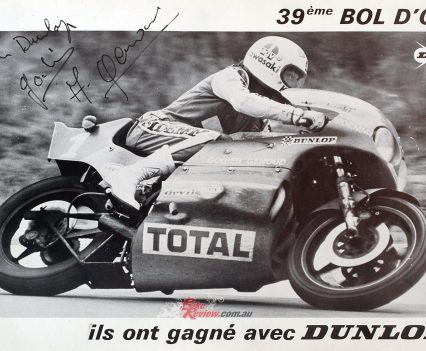

The Godier & Genound Kawasaki 1000 won the 1975 Bol d’Or 24-Hour race in the hands of its creators, Frenchmen Georges Godier and Alain Genoud, en route to winning their third FIM Endurance title that year.

Ranging from the truly bizarre to the avantgarde and excellent, 70s endurance racing bikes were extraordinary. The Kawasaki 1000 won the 1975 Bol d’Or 24-Hour race in the hands of its creators, Frenchmen Georges Godier and Alain Genoud, en route to winning their third FIM Endurance title that year. It’s a bike whose innovative format, coupled with its remarkable performance, established the future direction of modern two-wheeled chassis design, as well as cementing Kawasaki’s prized reputation in European markets for producing fast but reliable four-stroke sportbikes. It was in every way a milestone motorcycle.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

Yet in keeping with the ethos of Endurance racing which still largely prevails today, even at World level, the G&G Kawasaki was born of its creators’ part-time engagement in motorcycle sport as dedicated enthusiasts, in between having to earn a living doing the day job. Back in 1972 when the two first teamed up to contest the FIM Endurance series on an Egli-Honda, this meant that Alain Genoud, then 24, had to arrange a stand-in to cover for him as maitre d’hotel in a three-star restaurant in Geneva, just over the Swiss border from his French home in St.Julien-en-Genevois.

It’s the 100th anniversary of the Bol d’Or on September 16-18! Read about it here…

But it was the tips he’d got from waiting tables that had provided the cash which had earlier allowed him back in 1968 to buy a CB450 Honda offered for sale by a bloke called Georges Godier he’d met at his local bike club. A Reims-born bike mechanic four years older than Alain, Godier had been out riding in the Jura mountains earlier that year on a pair of CB450s with a mate called Pierre Doncque, whose bike had broken down on the outskirts of Geneva.

The Godier & Genoud Kawasaki helped established the future direction of modern two-wheeled chassis design, as well as cementing Kawasaki’s prized reputation in European markets for producing fast but reliable four-stroke sportbikes.

Georges Godier had impressed the Swiss Honda importer whose workshop he’d borrowed by the speed with which he repaired the bike, that he offered him a job on the spot – which is how Godier moved to the Swiss border country, and ended up selling his bike to Alain Genoud. It was the start of a beautiful friendship…

A former cyclo-cross and MX racer from an early age, Genoud had a competitive streak which led him to compete in the 1969 Swiss Hillclimb Championship on the CB450, before becoming one of Swiss chassis guru Fritz Egli’s first customers, buying an Egli frame for the parallel-twin Honda motor and finishing second in the 500cc Swiss Championship the following year with the resulting bike.

Check out our other Bol d’Or Racer Tests here…

He also made his Endurance road racing debut in 1970, finishing third in the Spa 24 Hours teamed with Maurice Maingret – a result which contrasted with Georges Godier’s rather less successful Endurance efforts with the invariably fragile self-prepared Norton Commando he shared with Pierre Doncque.

Although his persistence paid off eventually, with the Norton finishing fourth in the Spa marathon in 1971, Godier and Genoud decided to join forces in 1972 to mount a serious attempt on the increasingly prestigious FIM Endurance Championship with a new bike, consisting of an Egli frame fitted with a four-cylinder CB750 Honda motor from an insurance write-off which Godier painstakingly prepared for racing. Each had his own separate responsibilities in competing with the factory-assisted entries from Laverda, BMW and Ducati then contesting the series – Godier took care of the mechanical side, while Genoud concerned himself with organising entries, taking care of logistics, and recruiting the part-timer pit crew consisting of friends of the duo, and friends of friends.

One of these, named Serge Rosset, came quickly to the fore as a super-organised pit boss who would later win two World Endurance titles a decade later with the Performance Kawasakis, before running the ELF Honda 500GP team and in due course, manufacturing his own ROC-Yamaha V4 GP racers!

Check out our ELF 500GP Racer test here…

Only one thing wrong – traipsing round Europe to compete in the series had to be combined with the day job, and while Genoud searched for stand-in head waiters, Godier on the other hand had to get time off work as a mechanic with the Swiss Honda importer, whose boss made him put in the extra hours to make up for time lost, and wouldn’t even pay to have a sticker on the bike!

“Godier had to get time off work as a mechanic, whose boss made him put in the extra hours to make up for time lost, and wouldn’t even pay to have a sticker on the bike!”

He might have thought better of that when the Godier/Genoud duo won the FIM Endurance title that season, but after a series of retirements the following year defending their title in the five-race series, which were caused by inadequate preparation owing to the pressures of work, Godier tried to persuade his Honda bosses to be more supportive.

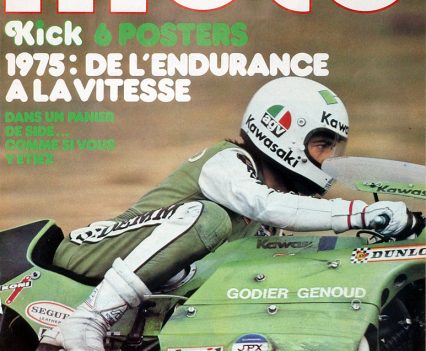

Nothing doing, so instead the duo made a deal with the French Kawasaki importer SIDEMM’s boss Xavier Maugendre who gave them the budget to go racing full-time, and build fast green bikes that would win races. Maugendre was already well versed in the promotional benefits of racing, after the success of his two-stroke H1 500cc triple-based Coupe Kawasaki one-make race series, which uncovered a plethora of future Gallic champions like Patrick Pons and Christian Sarron.

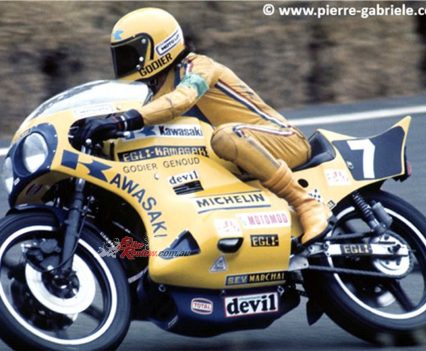

The first FIM Endurance title-winning Godier & Genoud Kawasaki wasn’t green, but yellow, in deference to Michelin which picked up their tyre budget. Photo Credit: Pierre Gabriele.

In fact, the first FIM Endurance title-winning Godier & Genoud Kawasaki wasn’t green, but yellow, in deference to Michelin which picked up their tyre budget – a fact which didn’t make them the last of the big spenders, since it was actually commonplace in that treaded tyre era for a bike to cover an entire 24-hour race on the same rear tyre! “We covered 2,980 km. on the same tyres in winning the Bol d’Or in 1975,” says Alain Genoud matter-of-factly. “C’était normale!” Using the same Egli twin-shock tubular backbone frame as on the Honda, fitted with a self-tuned version of the Kawasaki Z-1 motor, the duo constructed a bike which dominated the 1974 European Endurance series, winning the Barcelona and Bol d’Or 24-hour races and the Mettet 1000km in their hands, to convincingly earn them a second title.

Maugendre’s sales figures made him a winner, too, so for 1975 SIDEMM underwrote the construction of an all-new machine for a three-bike Kawasaki France team run by G&G out of the Kawasaki dealership they’d established just over the French border from Geneva.

This new bike, the first 100% Godier & Genoud Kawasaki, was designed by Godier’s mate and former riding partner Pierre Doncque.

This new bike, the first 100% Godier & Genoud Kawasaki, was designed by Godier’s mate and former riding partner Pierre Doncque, who after a short but successful racing career which saw him finish second in the 1969 French 500cc championship, had by now become a professor at the Amiens Technical University in France. Thanks to Doncque’s ability to think outside the envelope, the new racebike incorporated a completely innovative frame layout which advanced the evolution of motorcycle chassis design into the modern era, as well as setting a new benchmark for the Endurance category.

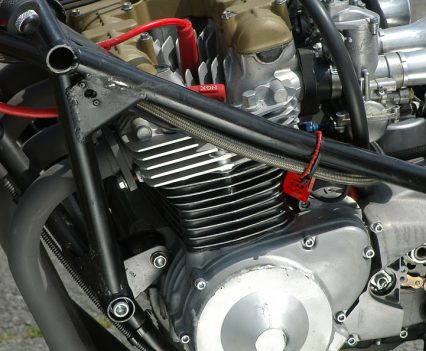

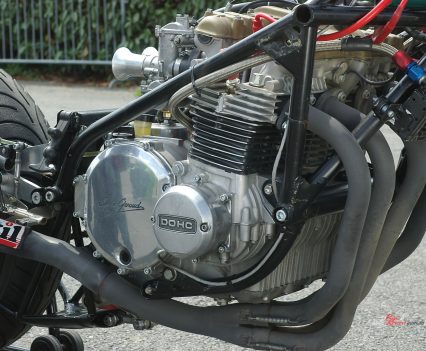

Its completely original perimeter-framed monoshock frame was essentially a tubular steel version of the later aluminium twin-spar Superbike/GP chassis commonplace today, complete with a rising-rate progressive link for the monoshock rear suspension, via a bell-crank design that Yamaha itself would replicate six years later on Kenny Roberts’ factory OW60 500GP bike.

Employing many Endurance racing innovations pioneered by G&G to save time at pits stops, including quick change wheels allowing more frequent use of fresh tyres, a US-style quickfiller via a membrane seal in the right flank of the fuel tank, and the use of a syringe to top up the oil level at each stop, the Doncques-framed bike was also designed to allow ease of maintenance and quick replacement of parts damaged in an accident, as well as greater rider comfort and better grip via long-travel rear suspension giving 200mm of wheel movement, and the much-needed extra ground clearance the wide Z1000 engine demanded.

Yet although the hefty air-cooled Z1 engine scaled 95kg on its own, the bike’s forward-looking chassis design also delivered a low 175kg weight with oil, a starter motor, twin headlamps, and the generator to power them, as well as a low frontal area yet with good rider protection, and dependable handling via conservative chassis geometry even for the time, with a 1480mm wheelbase and 28° head angle.

The new bike now measured the full 1000cc permitted by the rules, powered by an overbored 998cc version of the 900cc Z-1 Kawasaki motor, obtained via a Yoshimura kit with 69.8 mm-bore pistons.

The new bike now measured the full 1000cc permitted by the rules, powered by an overbored 998cc version of the 900cc Z-1 Kawasaki motor, obtained via a Yoshimura kit with 69.8 mm-bore pistons fitted to stock conrods mounted on a standard crankshaft. There were larger 37mm inlet and 31mm exhaust valves (one each per cylinder, of course!) fitted with stiffer springs, and operated by racing camshafts driven by a competition chain, and sitting within a reworked cylinder head with 10.5:1 compression that had been bored and flowed by Georges Godier himself.

A five-speed close-ratio Kawasaki race kit gearbox with a longer top gear was fitted, matched to a standard wet clutch. A set of four 31mm Keihin CR carbs with very long velocity stacks (aka trumpets) was fitted, with a specially-developed Devil 4-1 exhaust, which at that stage had no need of a silencer – FIM noise regulations were only introduced for the 1977 season. Accessibility of the engine for any reason during a race was infinitely better than any comparable bike, thanks to the monocoque unit comprising the seat and fuel tank, which could be quickly removed to give access to the whole engine – the cylinder head could even be lifted off with the engine still in the frame.

Producing 106hp at the rear wheel at 9,000 rpm, good for a top speed of 255 km/h round the Michelin test track at their Clermont-Ferrand base, the now green G&G Kawasaki was considered a hot favourite to retain the partners’ title in 1975 from the moment it appeared there in March that year in testing during the run-up to the Le Mans 1,000km race which opened the season – the Bugatti circuit there hosted two races each year, one long, one shorter, before Paul Ricard was constructed and the Bol d’Or 24 Hours moved there.

The now green G&G Kawasaki was considered a hot favourite to retain the partners’ title in 1975 from the moment it appeared there in March that year in testing during the run-up to the Le Mans 1,000km race!

But Godier suffered a rare lapse of attention at Le Mans, when he took too big a handful of throttle in his rush to get going after running across the track to leap aboard the bike, and highsided off the Kawasaki right at the start of the race – he was lucky not to get run over!

“Godier and Genoud converted a second Bol victory in to a third FIM Endurance title, by finishing third in the Thruxton 400-mile sprint race behind their victorious teammates on an identical bike – and then promptly retired from racing, right at the top! That’s how to do it….”

Retiring from the Barcelona race in July with a broken main bearing didn’t help their title chances, but at Paul Ricard in September it all came right, with the duo leading the Bol d’Or throughout from the second hour onwards, to score a decisive victory at record-smashing pace, with teammates Yvon DuHamel and Jean-Francois Baldé third. Two weeks later, Godier and Genoud converted this second Bol victory in successive years to a third FIM Endurance title, by finishing third in the Thruxton 400-mile sprint race behind their victorious teammates Vial/Luc on an identical bike – and then promptly retired from racing, right at the top! That’s how to do it….

In successive years, the duo concentrated on preparing Endurance racers for customers, especially the factory-supported Performance team run by their mate Serge Rosset in neighbouring Annemasse, which won the World Endurance title in 1991 and 1992 with G&G-developed bikes. And when Kawasaki Europe tentatively entered World Superbike racing in 1989, it was Godier and Genoud which prepared and entered the ZXR750s for them to do so.

Meantime, the partners had become manufacturers in their own right, building more than 500 beautifully-engineered Kawasaki-powered 998-to-1135cc Godier & Genoud roadbikes from 1979 onwards, before Georges Godier was tragically killed in a road accident testing a customer’s machine in March 1993, literally just down the road from their Geneva area dealership. Alain Genoud struggled for a while to carry on without his longtime technical guru by his side, but then caught the wave of worldwide interest in big-bore Post-Classic Historic racing very successfully.

Alain still carries the Godier & Genoud name to this day. Residing in St.Julien-en-Genevois. Photo: David Morcrette.

Founding a new company, AG Diffusion, still in the old St.Julien-en-Genevois site, he’s become a top preparer of four-cylinder Japanese bikes of any marque – but especially Kawasakis! – as well as restoring many of the Godier & Genoud streetbikes, and improving them where necessary. He also restarted racing again for the first time since that 1975 championship year, winning the 2003 French ProClassic title on his 1135cc G&G, as well as on two occasions the Classic Bol d’Or that’s run each year at Magny-Cours. History repeats itself!

And that applies as well to the history on wheels which the 1975 Bol d’Or-winning Godier & Genoud Kawasaki represents, which Alain has now refreshed to trackworthy condition after spending so many years parked in the window of the G&G Kawasaki dealership, and which he kindly brought to the Carole circuit just outside Paris for me to ride. Climbing aboard what seems at first to be anything but a 40-year old motorcycle, so modern and imposing is its undoubted presence, you’re immediately aware of the low 760mm seat height which, coupled with the sculpted seat and relatively high footrests for the period in pursuit of extra ground clearance even with the treaded tyres still universal in Endurance racing, makes you feel wedged in place, unable to move around the bike.

“We didn’t hang off the side like you all do nowadays,” said Alain with a twinkle in his eyes as he strapped a thick rubber pad on the seat to lift me up a little and make more space for my knees. “Racing then was about getting comfortable for the long spell and conserving your energy – remember we only had two riders per team for a 24-hour race, not three or even more like they have nowadays.”

Once settled aboard, the Kawasaki seems curiously schizophrenic – it’s wide and slim at the same time! Slim, because the metal fuel tank is very narrow, meaning your hands don’t need to be wrapped around it as on bulkier other such reservoirs of the era. That’s because only the very rear part of the upper section in fact contains petrol, with the front part taken up by the bike’s battery and electrics, all easily accessible for quick changes, with the major part of the 20-litre fuel load carried further back between your legs, above the gearbox, with an electric fuel pump to get it to the carbs.

“Once settled aboard, the Kawasaki seems curiously schizophrenic – it’s wide and slim at the same time!” said Cathcart.

This provides a lower cee of gee and ensures the balance of the Kawasaki remains constant between pitstops, making for more predictable handling just as on modern MotoGP racers with a similar layout. But at the same time the bike feels wide, and quite tall, thanks to the broad fairing which offers great rider protection, and would have been a key factor in that 255 km/h top speed. Genoud says the screen would have been 50mm lower back then, that’s all.

However, the Kawasaki’s beneficial bulk doesn’t affect the handling, which while ultra-stable in faster turns thanks to the long wheelbase and conservative steering geometry – even on the power where it didn’t understeer at all as I worked my way up the race pattern one-up left-foot gearshift – was acceptably handy in the many tighter turns so plentiful at Carole. It’s not a nimble bike, by any means, but neither is it a barge – it just felt very planted and secure, and quite easy to change direction with for a four-cylinder mid-‘70s bike, thanks to the lower cee of gee.

“However, the Kawasaki’s beneficial bulk doesn’t affect the handling, which while ultra-stable in faster turns thanks to the long wheelbase and conservative steering geometry.”

But you’ll want to give yourself some extra space when stopping hard, for the modern Brembo stainless steel 300mm discs (replacing the original JPX cast iron discs mounted to early cast alloy wheels from the same French specialist supplier, which Genoud has replaced for safety reasons), gripped by period twin-piston calipers, felt very wooden and didn’t inspire confidence even when squeezed as hard as you can, while combating a slow throttle response when blipping the engine as you come down the gears under braking. A period Ducati’s AP-Lockheed calipers with cast iron Brembo discs make for a much better ‘70s-style brake package, Alain….!

After first lifting the choke lever on the carbs to get the fuel pump ticking to prime them, then thumbing the starter button to crank the motor into life, I found the relatively lightly tuned four-cylinder engine is as tractable and forgiving as I remember the same motor was in my TT F1 P&M Kawasaki that I raced in the Isle of Man and the British TT F1 series back in 1979.

“It’s not a nimble bike, by any means, but neither is it a barge – it just felt very planted and secure, and quite easy to change direction with for a four-cylinder mid-‘70s bike.”

That allowed me to hold second gear throughout the tight Carole infield section, backing on and off for turns with no trace of a hiccup anywhere above the 4,000rpm mark on the Kröber tacho that’s the bike’s only instrument. But although that’s the gateway to the G&G racer’s power curve, you need to get the engine revving above 6,000rpm to get serious performance, and must run it to the 9,000rpm redline in every gear – with only a five-speed gearbox you can’t think of short-shifting, despite the awesome tractability.

“you need to get the engine revving above 6,000rpm to get serious performance, and must run it to the 9,000rpm redline in every gear.”

I didn’t have space at a tight track like Carole to get a true top gear, but I bet it feels very long-legged when you do get the chance to slot that long fifth ratio in the factory kit’s gearbox in on a faster track, as Alain Genoud confirms is the case. The engine feels totally unburstable and rugged but revvy. Nice.

But not as nice as the Kawasaki’s rear suspension, which is light years ahead of anything I raced back then, or have ridden since of equivalent vintage. For a start, it’s like racing an antique armchair, so compliant and comfortable is the extra damping delivered by the fully-adjustable Koni shock replacing the original DeCarbon for which parts are no longer available. Just the thing for twelve sessions or more Out There in a 24-hour race. But on a heavily used track like Carole with more than its fair share of bumps and ripples, the Kawasaki felt ultra-safe and very composed, the rear Avon AM23 delivering its usual great grip on the angle in unflurried guise, as I felt the Doncques frame’s progressive-rate monoshock rear end rising and falling over surface irregularities.

Get a bike 40 years younger than this one damping as well, and you’d be well pleased. The Kawasaki forks on the other hand felt less well set up, with insufficient rebound damping that Alain Genoud declared was most likely caused by not using a heavy enough weight of oil in the 31ºC ambient temperatures of our test day. Still, the front Dunlop KR124 stuck well, and at least there was no chatter from what is undeniably a big, heavy old bike using the stable chassis’s good corner speed to keep up momentum in slower turns.

Really, what we have here is the prototype modern streetbike, displaying technology whose worth was proven by the Kawasaki’s success in long distance racing at record speed, but which took more than another decade to reach the street in an affordable mode for Joe Public. What a missed opportunity this bike represents – Kawasaki had the keys to the two-wheeled future in their hands, had they but known it at the time.

“What a missed opportunity this bike represents – Kawasaki had the keys to the two-wheeled future in their hands, had they but known it at the time.”

Instead, it took another six years for Spanish designer Antonio Cobas – widely recognised as the creator of the modern race chassis – to conceive and produce the first aluminium twin-spar frame using the same concept and an identical layout to the Godier & Genoud Endurance champion’s tubular steel chassis, and more than a decade for Bimota to bring it to the street via in its Yamaha-engined YB4 Superbike. But Endurance racing delivered the basic technology first in this motorcycle, and here is where the future started, back in 1975…..

1975 Godier & Genound Kawasaki 1000 Endurance Racer Specifications

ENGINE: Air-cooled DOHC transverse in-line four-cylinder four-stroke, with two valves per cylinder, and central chain camshaft drive, 998cc, 10.5:1 compression ratio 69.8mm x 66mm bore & stroke, Dyna CDI + 12v battery, 4 x 31mm Keihin CR, 5-speed close ratio, Multiplate oil-bath with heavy-duty springs clutch.

CHASSIS: Chrome-moly tubular steel perimeter frame, 38mm Kawasaki telescopic forks (f) Fabricated tubular steel spaceframe swingarm, with fully adjustable Koni monoshock and bell-crank linkage for rising-rate progressivity (r) 2 x 300mm Brembo stainless steel discs with two-piston Brembo calipers (f) 1 x 260mm Brembo stainless steel disc with single-piston AP-Lockheed caliper (R) 3.10/4/80-17 Dunlop KR106 radial on 3.50in cast aluminium Marchesini wheel (F) 3.50/3.25-18 Dunlop KR124(f) 150/70-18 Avon AM23 (r) Campagnolo cast magnesium wheels. 28 degree head angle. 1480mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 106 bhp@9,000rpm (at rear wheel), 255km/h top speed (Michelin Clermont-Ferrand test track 1975), 190kg dry with starter motor, twin headlamps and alternator.

Owner: Alain Genoud, St.Julien-en-Genevois, France

1975 G&G Kawasaki 1000 Endurance Racer Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.

January 10, 2024

I still remember seeing the G&G chain adjuster which worked both adjusters at the same time and allowed (when needed) much quicker rear tire changes. Never saw anyone else doing that. After this article I wish G&G had done more outreach into the street machine world – this could have been a major competitor for Harris, Egli, Moto Martin et al.