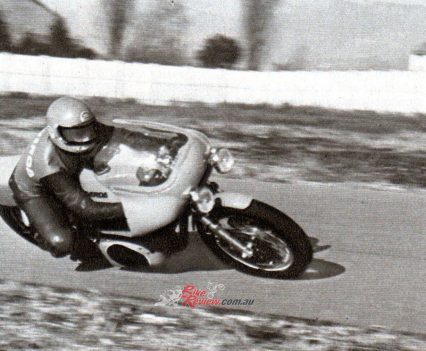

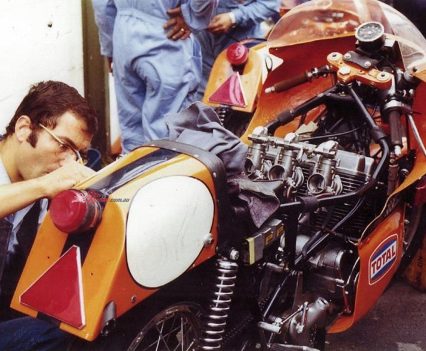

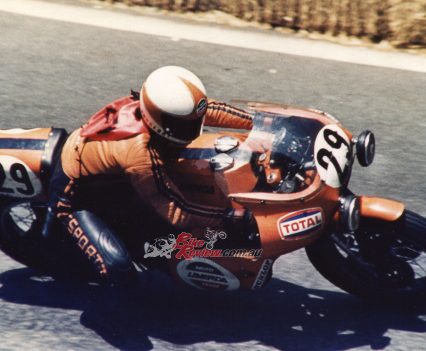

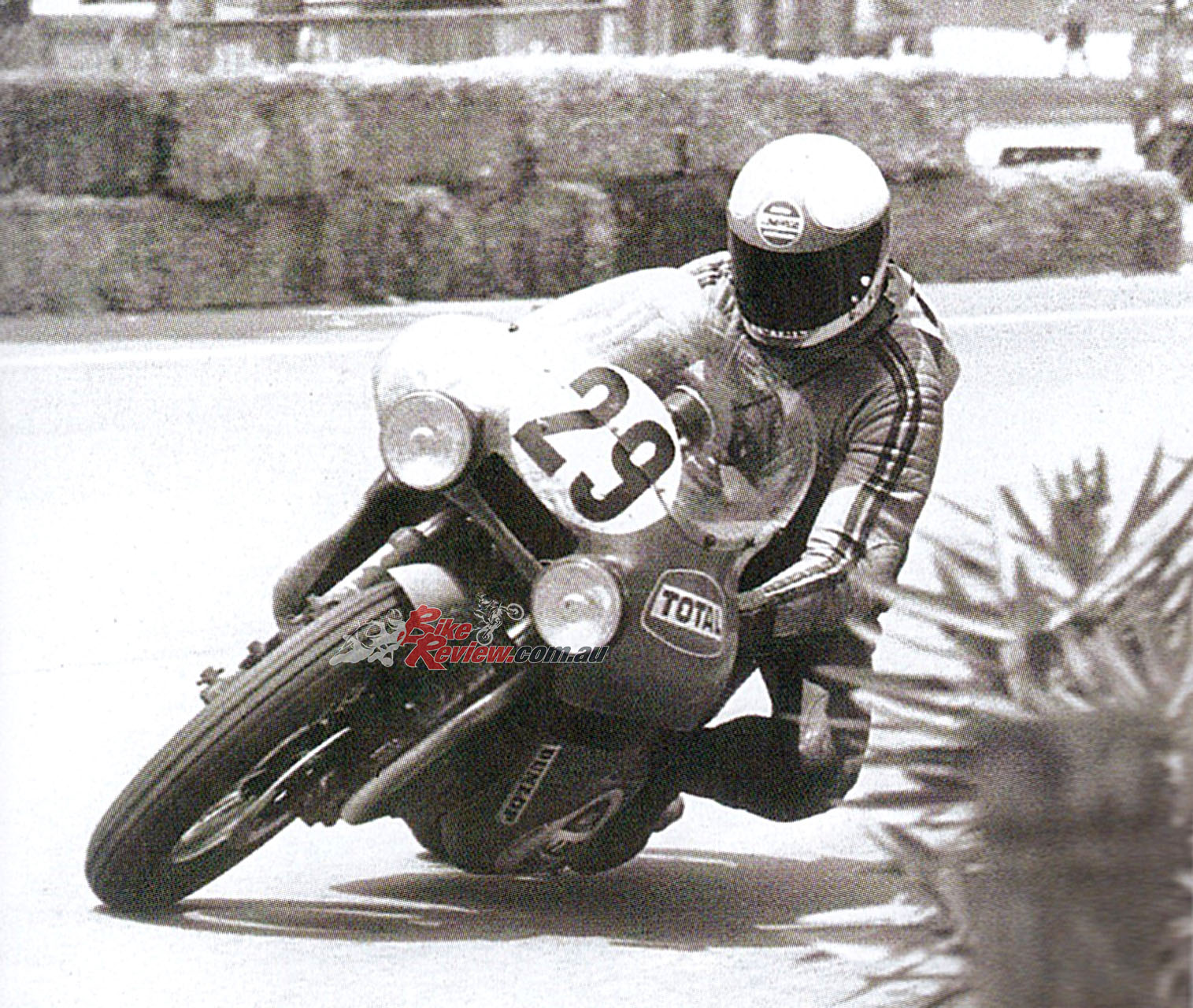

The big, heavy beast of endurance racing in the mid '70s. Cathcart had the chance to take the Laverda 3C 1000 Endurance Machine for a spin in its original racing form... Photo credit: Stefano Gadda

Massimo Laverda had a finger on the pulse of the motorcycle market, leading other companies in making bikes people wanted to buy. We dive into Laverda’s 3C 1000 triple – the world’s first one-litre ultrabike, launched three years earlier than Kawasaki’s Z1.

We dive into Laverda’s 3C 1000 – the world’s first one-litre ultrabike, launched three years earlier than Kawasaki’s Z1.

Fifty years ago, the evolution of what we think of today as a modern motorcycle, had only just begun gathering pace. Honda had commenced its own march up the capacity scale with the CB450 DOHC parallel-twin launched in 1964, the year that 25-yearold Massimo Laverda was appointed by his father Francesco to take over running the motorcycle division of his family’s agri-machinery company.

Check out all of our Throwback Thursdays here…

Massimo’s understanding of the marketplace due to his own passion for bikes – he was already a Vincent and BMW R69S owner – meant Moto Laverda was the first-ever manufacturer to produce a 750cc sportbike. That came about in May 1968, when production began of the scaled-up version of its 650cc five-speed SOHC wet sump parallel-twin previously unveiled in prototype form at London’s Earls Court Show in November 1966.

It didn’t take long for other manufacturers to follow suit, led by Britain’s BSA/Triumph combo which launched its Trident/Rocket-3 750cc triples in September ’68, powered by a four-speed vertically-split OHV pushrod motor concocted by Triumph engineer Doug Hele, essentially by dint of adding an extra cylinder to his company’s best-selling 500 twin, whose kick-start it retained. But in November 1968 Honda unveiled the electric-start SOHC four-cylinder CB750 at the Tokyo Show, and the rules of the motorcycle marketplace were changed forever.

But just as he’d trumped Honda’s CB450 twin with a 650cc model, Massimo Laverda was already working on his counter to the CB750, as the first person to visualise that 1,000cc would be the two-wheeled capacity benchmark of the future. With his company’s twin-cylinder models selling as fast as Laverda’s small Breganze factory could build them (19,000 in all before their mid-‘70s replacement by the one-litre triples, and 500cc twins), he instructed the firm’s chief engineer Luciano Zen to create a 1000cc hyperbike obtained by following the Hele/Triumph route of adding an extra cylinder to Laverda’s existing parallel-twin motor, to create the world’s first one-litre multi-cylinder model.

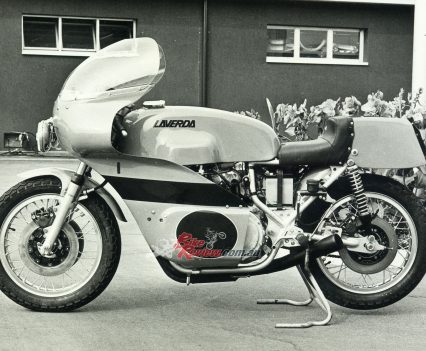

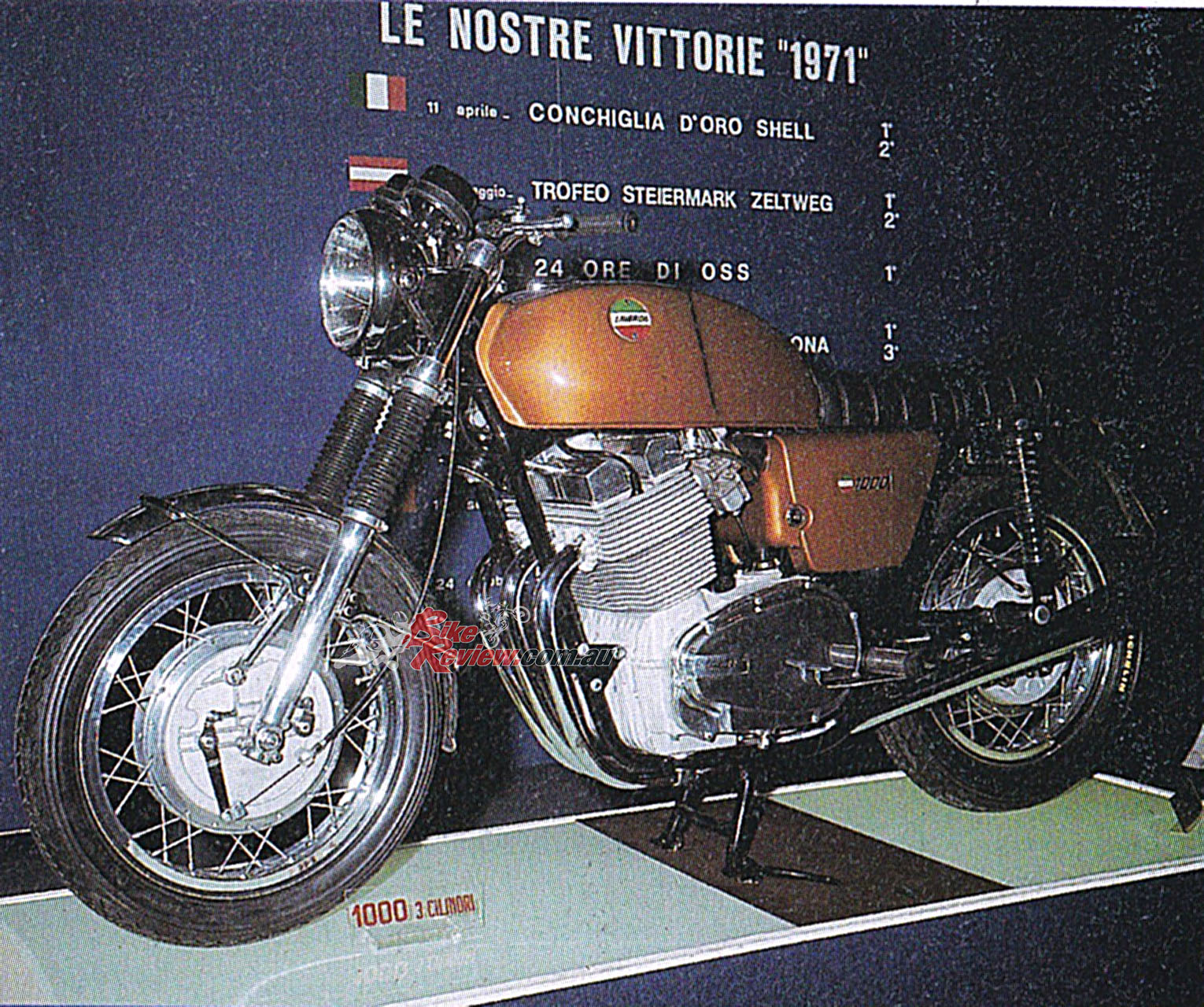

The prototype Laverda 3C 1000 triple was unveiled at the November 1969 Milan Show, and in the eyes of some overshadowed the Honda CB750 with which it shared star billing there. With the engine’s single overhead cam driven by a duplex chain on the right side of the cylinders, it shared the same 75x74mm dimensions as Laverda’s 650 twin for a capacity of 981cc. A horizontally-split design with a five-speed gearbox and electric start, it produced a claimed 75hp@6,700rpm, good for a top speed of 205 km/h, and sported three separate exhausts, just like Ago’s World champion MV Agusta GP racers.

Laverda 3C 1000 debuts at the Milan Show. It produced a claimed 75hp@6,700rpm, good for a top speed of 205 km/h, and sported three separate exhausts, just like Ago’s World champion MV Agusta GP racers.

Public response was ecstatic, so the Laverda family knew they had a winner – a confidence duly upheld by the total of 12,550 Laverda triples of all different types which they’d go on to build between 1972 and 1988. To counter the strong secondary vibration from a 120° crankshaft with even throws, the first-generation Laverda triple had a six-piece pressed-up 180° crank, supported on four roller bearings with a ball bearing on the timing side, and an extra outrigger roller bearing in the primary cover, with the two outer pistons rising and falling together, and the central one diametrically opposed to them at 180°. This resulted in an extremely individual gruff-sounding offbeat exhaust note from the 3-ino-1 exhaust it began production with..

As development got underway in 1970, the Laverda motor’s top end evolved into a DOHC format with shim-and-bucket adjustment, but the same offset camdrive now via a toothed belt, before switching in 1971 to a more compact design. This saw the robust one-piece cylinder block inclined forward by just 20° (versus the twin’s 25°), and a single-strand camchain positioned between cylinders 1 and 2 starting on the right as viewed from the rider’s seat.

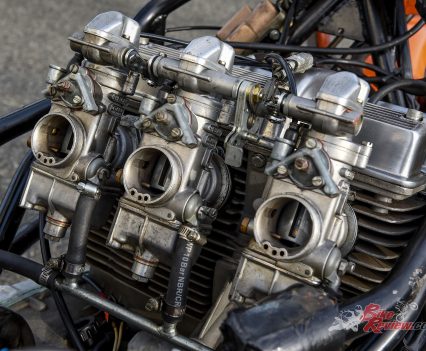

The six-valve cylinder head had 38mm inlet and 35mm exhaust valves set at an included angle of 70°, with cast iron cylinder head skulls to prolong valve seat life. With three of Dell’Orto’s new 32mm PHF concentric carbs, a transistorised Bosch electronic CDI, an oil-bath clutch with triplex chain primary drive, and a 9:1 compression ratio. The version of the wet sump 3C 1000 engine which entered production in April 1972 after a typically lengthy Latin gestation period produced a claimed 80hp@7,200rpm, with a hefty 84.3Nm of torque at just 4,200rpm.

A conventional twin-loop frame with large-diameter tubular backbone, Ceriani suspension and Laverda’s own brakes, this wire-wheeled machine lived up to its ultra-butch looks in delivering benchmark performance with handling to match.

Fitted in a conventional twin-loop frame with large-diameter tubular backbone, Ceriani suspension and Laverda’s own brakes, this wire-wheeled musclebike lived up to its ultra-butch looks in delivering benchmark performance with handling to match, aided by its 214kg dry weight, 5kg less than the Honda four. The 3C 1000 was also 20 per cent more powerful than the CB750, while producing the same claimed horsepower as the Kawasaki Z1 that dead-heated with the Laverda in entering showrooms, albeit weighing 15kg heavier, and with less assured handling. The Italian model’s only major reliability problem was with the Bosch CDI on the early bikes, which surely cost the German supplier lots of cash to remedy via a total recall.

“The 3C 1000 was 20 per cent more powerful than the CB750, while producing the same claimed horsepower as the Kawasaki Z1 that dead-heated with the Laverda in entering showrooms…”

Almost inevitably, given Laverda’s proud tradition of going Endurance racing both to prove the worth of its products as well as to develop them further, as soon as 3C production began the Italian factory started racing its new triple – winning first time out, too! This came in June 1972 in Austria, in the Steiermark Cup Sport Production race at Zeltweg, where factory racing stalwart Augusto Brettoni on a stock-framed Laverda 3C triple with 750SFC race bodywork, led home Roberto Gallina on a Segoni-framed SFC750 twin.

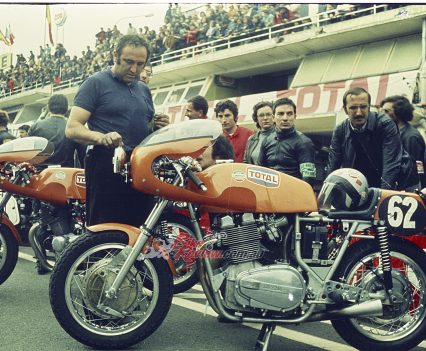

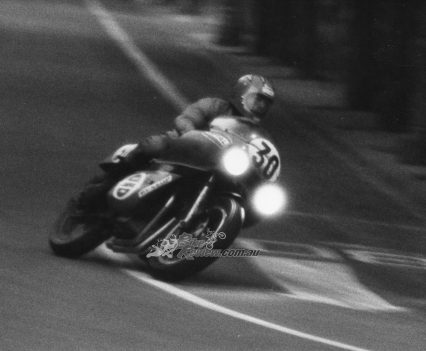

The Endurance debut of the 3C 1000 took place in September 1972’s Bol d’Or 24hrs held on the Bugattti circuit at Le Mans, with Brits Tony Melody and Doug Cash riding a bike with a modified chassis.

The Endurance debut of the 3C 1000 took place in that September’s Bol d’Or 24hrs held on the Bugattti circuit at Le Mans, with Brits Tony Melody and Doug Cash riding a bike with a modified chassis, which retired after five hours with gearbox problems. The new frame raised the engine 30mm to reduce the chances of decking the alternator mounted on the right end of the crank in turns, but this only added to the bike’s top-heavy feeling compared to the sweet-handing SFC twin.

Laverda cut back on racing in 1973, since with the 750 twins selling so well, and advance orders for the 3C so strong, Francesco Laverda constructed a spacious new 12,000m² factory on the outskirts of Breganze for his company’s motorcycle operation, which until then had occupied a section of the agri-machinery plant where the bikes were essentially hand-built individually. Moving to a series production format allowed him to potentially double production volume with the same 300-strong workforce, thanks to a further substantial investment in new machinery. The disruption this entailed amidst the need to satisfy orders, plus the problems with the Bosch ignition, all combined to reduce Laverda’s focus on racing for a couple of years.

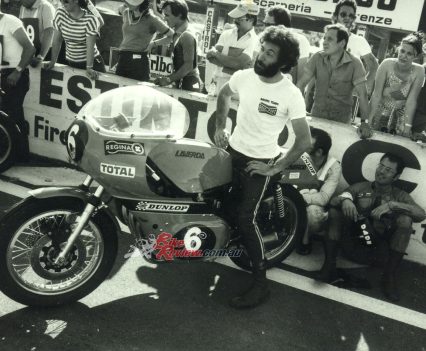

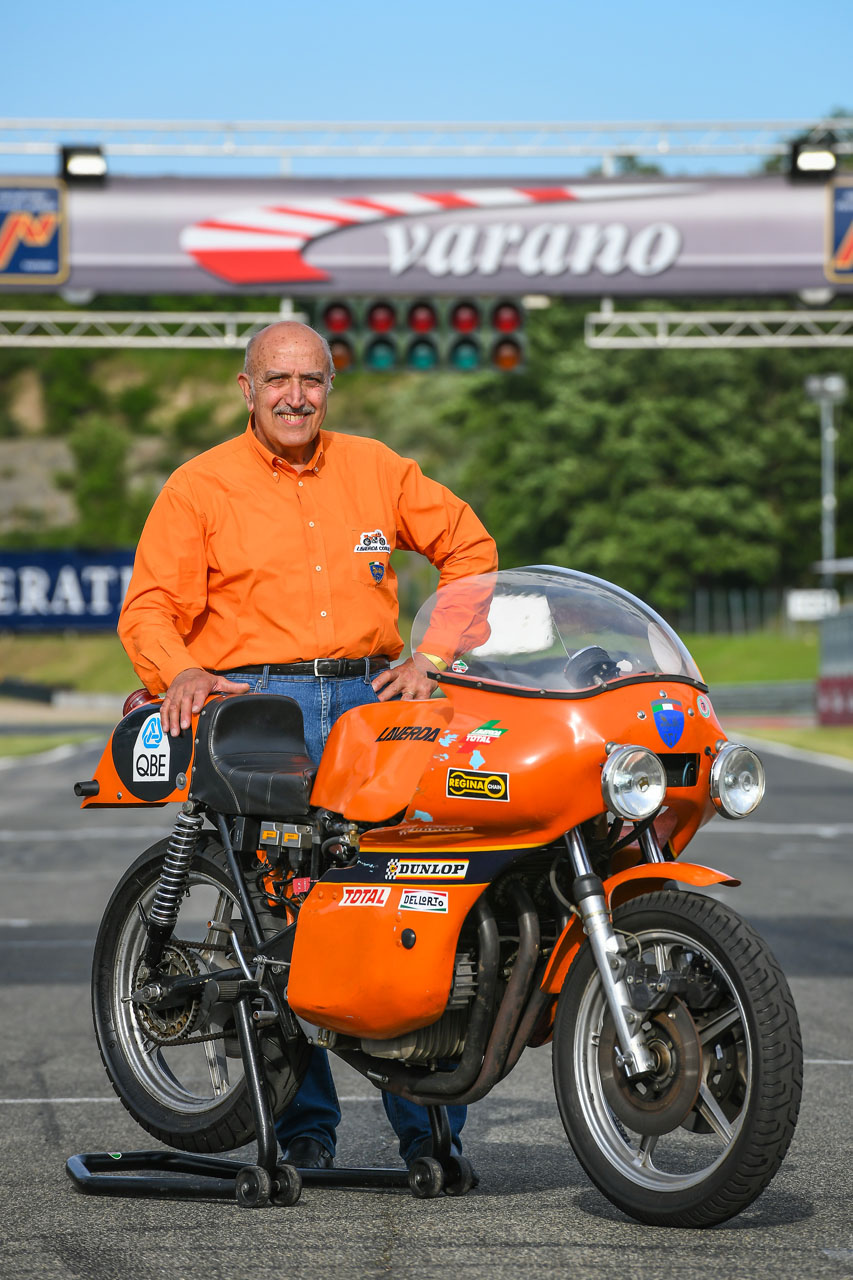

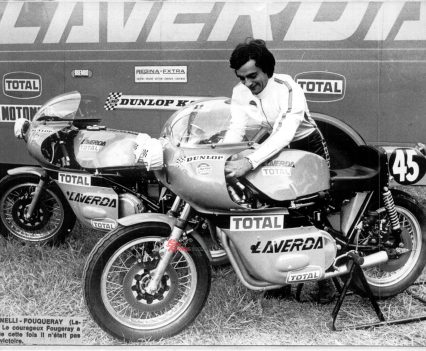

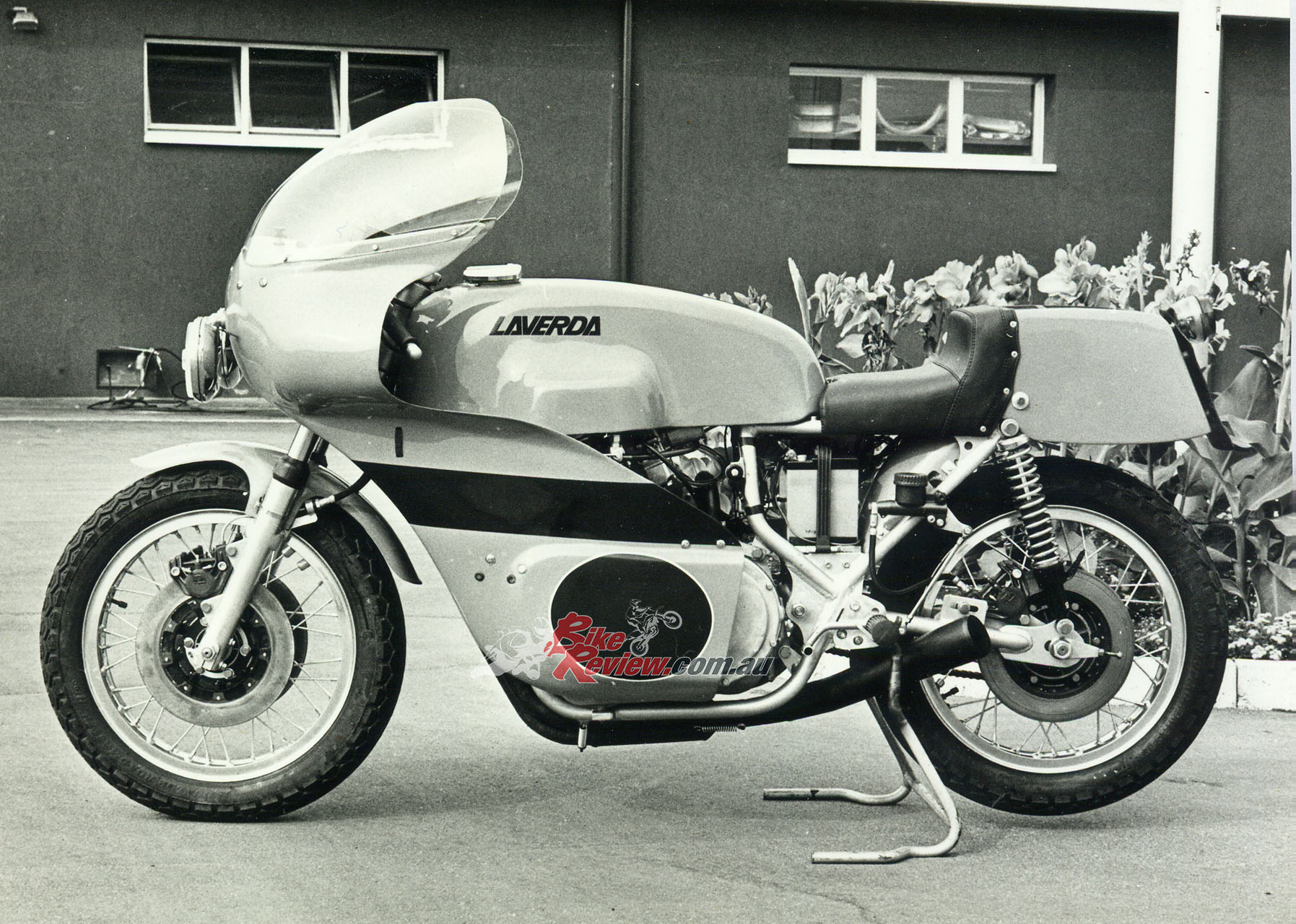

But for 1975, with production back on an even keel, Laverda returned to the race track with a purpose-built bike – the 3C 1000 Endurance. Piero Laverda, Massimo’s younger brother, and today with his son Giovanni the driving force behind the array of bright orange bikes waving the Laverda flag at Historic events around Europe, takes up the story.

“Our first 3C racer came in 1972, and was very close to a standard bike, then the second edition we prepared for 1974 was an improved standard frame with the alternator brought inside to have more ground clearance, but with an improved engine. Then for 1975 we developed a new spaceframe chassis to try to resolve the handling problems, because the original 3C 1000 frame was made for the street, not to race. This meant that on very fast corners over 180 km/h in speed, the bike would start weaving, because the engine was moving a little bit in the frame, so we needed a very rigid connection between frame and engine to have zero movement. We made only five examples of this special chassis, and for 1975 we decided to contest all the FIM Endurance Championship rounds with this machine, with a two-bike team but five riders, so there is always a spare rider available in case of necessity.” said Piero

Piero Laverda is the driving force behind the orange flag still being flown at classic racing events around the globe.

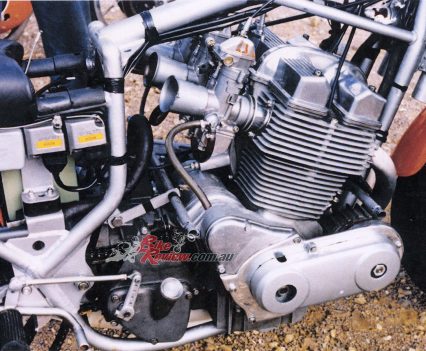

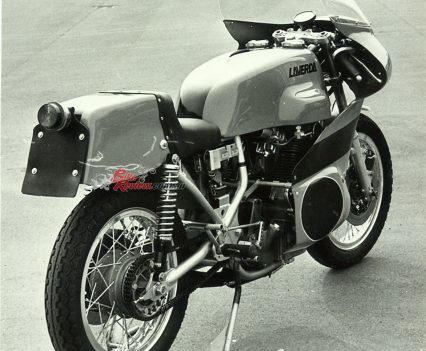

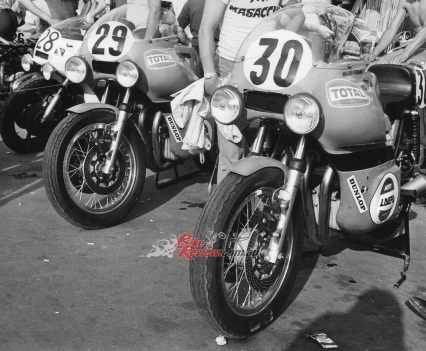

The new chrome-moly tubular steel open-cradle spaceframe chassis employing the engine as a semi-stressed member (which the robust crankcases were well suited to doing), was designed by Luciano Zen, and while at 13kg it weighed 9kg less than the standard frame, it was also 50mm lower and 40mm shorter, too. The 38mm Ceriani fork adjustable for preload and rebound damping sat at a 26.5° rake with 112mm of trail, while the tubular steel swingarm operated twin Ceriani shocks. Wheelbase was 1486mm, with an even 50/50 distribution for the 200.5kg half-dry weight, with oil/no fuel.

Twin 280mm Brembo cast iron discs with two-piston calipers were fitted up front, and another at the rear, with 18-inch Borrani wire wheels, and Dunlop rubber. That weight not only included the alternator in front of the cylinder block, with a polished alloy cover over the belt-drive running off the crank, but also the twin SEV-Marchal 100W headlamps parked either side of the letterbox slot in the all-enveloping fairing, feeding air to the oil cooler positioned in its nose.

The modified 981cc three-cylinder engine saw compression raised from 9.5:1 to 10.2:1, and oversize 40mm inlet valves and 35.5mm exhausts operated by race camshafts with higher lift and longer dwell. Larger 36mm Dell’Orto PHB carbs were fitted (vs. 32mm stock). The close-ratio five-speed gearbox featured undercut dogs to enhance engagement, with a duplex final drive chain and triplex primary, and beefed-up 13-plate oil-bath clutch, together harnessing the increased output of 96hp delivered to the gearbox sprocket at 8,500rpm. Ignition came via an early Bosch BTZ electronic CDI.

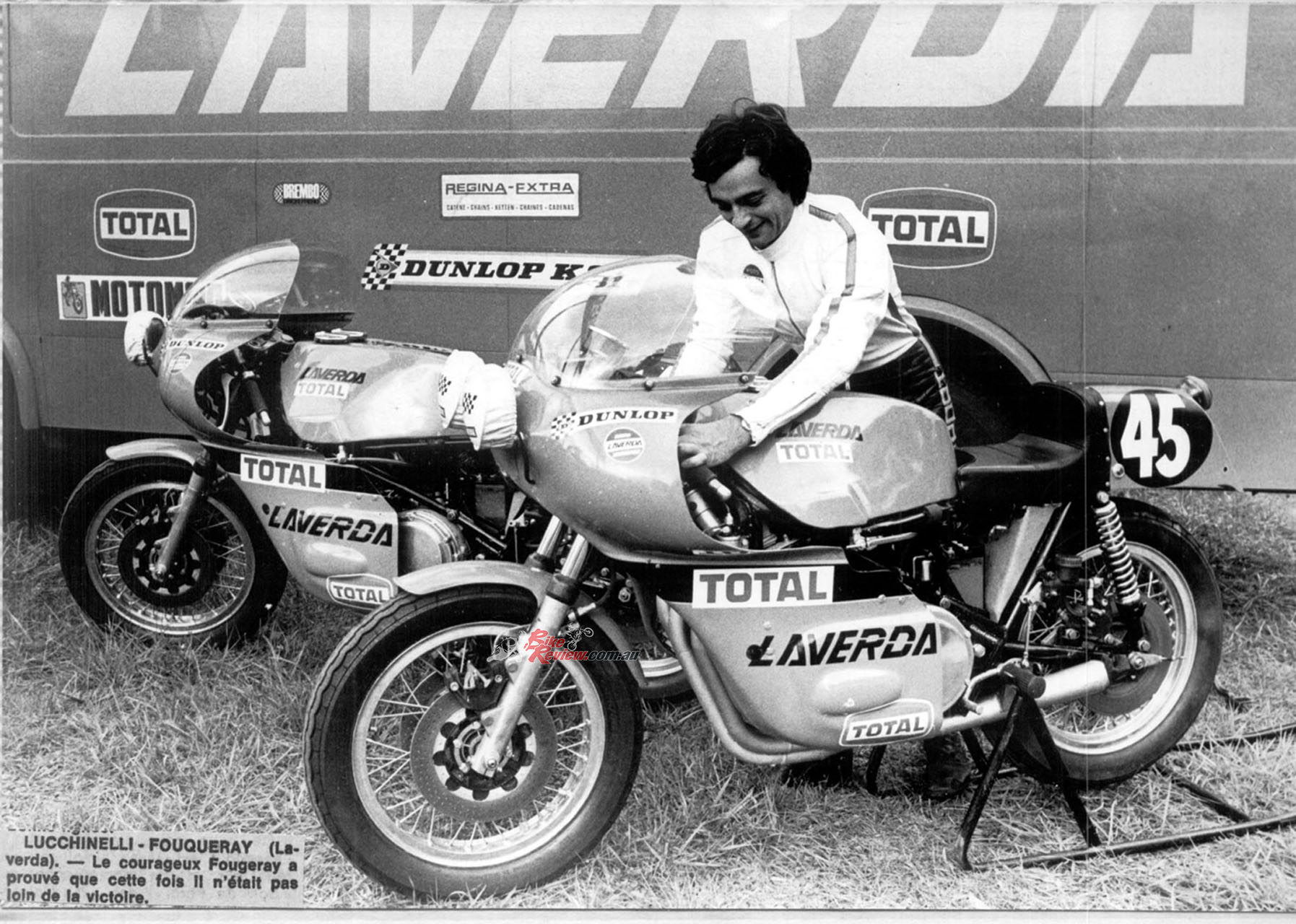

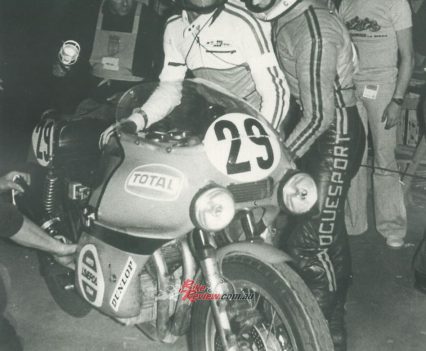

After Laverda test rider Fernando Cappellotto had begun testing ‘Il Spaceframe’ from February 1975 onwards, the first round in the five-race FIM Endurance series took place in June on home ground at Mugello. There, Augusto Brettoni and Nico Cereghini finished third in the 1,000km race on the new Laverda’s debut, behind the victorious works Ducati of Grau-Ferrari, and Guzzi-mounted runners-up Sciareza-Romeri, though teammates Georges Fougeray and Marco Lucchinelli retired with engine problems. This was the future 500GP World champion’s first ride for a factory team.

The Laverda 3C 1000 Started Lucchinelli’s amazing career! Read more here…

Fortunes were reversed at the next round in the July heat of Barcelona at the Montjuic 24hrs, with Lucchinelli-Fougeray finishing sixth after an eventful race, while it was the turn of Brettoni-Cereghini to retire with engine problems.

Next up came the 3C Spaceframe’s finest hour, in August’s 24hrs of Liège at Spa-Francorchamps, run in testing conditions including torrential rain showers which negated the speed advantage of the four-cylinder Japanese bikes. There, the two Laverdas both finished on the rostrum, with Roberto Gallina taking a break from GP racing to team with Cereghini to place second behind the victorious Japauto Honda of Ruiz-Huguet, with Lucchinelli-Fougeray third.

August 1975 saw an awesome success for Laverda at the Spa 24h. Roberto Gallina takes home 2nd with Cereghini.

“The protection we received from the very protective fairing was a key factor in this race,” recalls Roberto Gallina today. “It shielded your arms from the constant rain, and the hand problems I already suffered from back then owing to injuries, which made it hard for me to do 24-hour races, were not so apparent in the wet. The bike ran like clockwork – it was the first time I’d raced the Laverda triple, and the engine was quite nice except for the vibration from 7,500rpm onwards. But it was such a heavy bike to ride compared to the sweet SFC twin I’d raced exclusively for Laverda until then. With a full tank it weighed over 220kg, and was quite a handful in changing direction – it wasn’t very agile. But it was marvellous to finish on the podium with my protégé Marco – it was the start of a nice collaboration that led us to the 500GP World title together six years later!”

But, after the double podium at Spa, September’s Bol d’Or at Le Mans was a disaster for Laverda. There, two machines were entered in the race, as usual – but Lucchinelli-Fougeray were entrusted with a prototype 120° motor with evenly phased crank throws, such as would later be adopted on production Laverda triples from 1982 onwards, after the correct balance factor was finally discovered. In 1975 this was solidly mounted in the spaceframe chassis, with the result that the high frequency secondary vibration not only tired the riders, but also repeatedly blew the Bosch ignition’s black boxes, eventually resulting in their retirement after 12 fraught hours.

Brettoni-Cereghini on a conventional 180° bike retired just two hours from the end when well placed, with a broken piston. And that was that, with the Laverda Corse team opting not to make the long journey to the UK for the final round of the FIM series at Thruxton. The 3C Spaceframes would race no more, while the factory race department devoted itself to developing the fabulous V6 Laverda 1000 that would make its debut two years later in the 1978 Bol d’Or.

Two broken bikes in 1975, that was that… The Laverda Corse team opting not to make the long journey to the UK for the final round of the FIM series at Thruxton.

“Our disadvantage with the three-cylinder Spaceframe against the four-cylinder Honda and Kawasaki bikes was not so much power, as weight,” says Piero Laverda, an ever-present in the pits at that year’s FIM Endurance rounds. “Our four-cylinder competitors were about 172-175 kilos without fuel, but we were 200.5kg! I remember the Honda RCB factory Endurance model looked like a GP machine prepared by the same people who later made their 500GP bikes in the Reparto Corse. Our bike was really just a road racer derived from an improved standard machine, so in the 24 hours we often got a good result, because remember, in Endurance racing to finish first, you first must finish!”

Cathcart got a chance to experience the 3C 1000 at Italy’s annual Moto Storiche festival at the Varano circuit.

Racer Test

My chance to experience these extra kilos from the hotseat came at Italy’s annual Moto Storiche festival at the Varano circuit in the hills outside Parma. There, one section of the Paddock becomes a sea of orange each year, as Laverdisti from all over Europe congregate to celebrate in action the memory of Italy’s most famous Endurance racing brand, now sadly defunct while its trademark’s owner Piaggio continues to rebuff attempts by well-funded firms like Fantic to purchase it from them, and relaunch the brand.

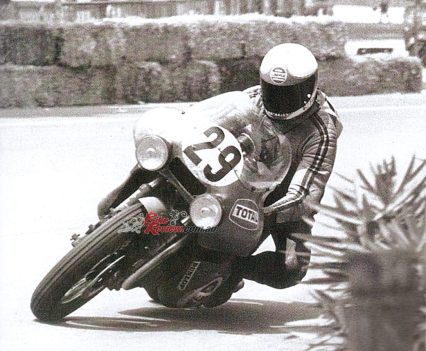

Piero Laverda and son Giovanni had brought both the legendary V6 for Piero to demo, and the 3C Spaceframe which Giovanni normally rides. But this time he gave me the honour of two sessions on the busy 12-turn 2.38km Varano circuit aboard a bike whose engine remains essentially untouched since it was built up in 1976 after Laverda had retired from racing, ready for display in the factory lobby until the company closed in 1985, and the Laverda family retrieved it for their private collection. In deference to this, I was asked to keep revs down to 6,000rpm, rather than the 8,000rpm the watching Roberto Gallina told me he usually observed in 24hr marathons.

AC had the honour of two sessions on the busy 12-turn 2.38km Varano circuit aboard a bike whose engine remains essentially untouched since it was built up in 1976 after Laverda had retired from racing.

Such a circuit is quite unlike the fast, open courses like Spa and Mugello that the heavy, robust Laverda 3C long-distance express was most at home on, and it didn’t help that it was way overgeared for Varano, since to avoid changing sprockets the Laverda family leaves the tall Spa-Francorchamps gearing on for their annual visit to the Bikers Classic event there, and makes do with it elsewhere.

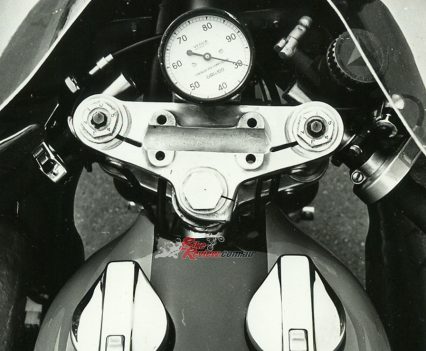

This meant that I could only use third gear once a lap past the Varano pits, and elsewhere had to use bottom gear four times each lap – though the forgiving nature of the three-cylinder 981cc motor saw it pull cleanly away from not much higher than the 1,200rpm idle out of Pit Lane. But you must let the needle on the road bike tacho that’s the bike’s only instrument – no redline reminder, though! – hit the 3,000rpm mark before it comes on the cam.

“The forgiving nature of the three-cylinder 981cc motor saw it pull cleanly away from not much higher than the 1,200rpm idle out of Pit Lane.”

It’s very measured in the way it builds revs – this is a long-legged motorcycle which seems strong and robust, happy to surf the relatively meaty midrange torque curve, though you must be ready to counter the slight patch of roughness just under 4,000rpm that’s probably derived from the 3-1 exhaust, as well as the cams timing. Otherwise, the 180° motor is very smooth and torquey, while the exhaust utters that unmistakeable offbeat lilt. Even without the bright orange paint scheme – identifying it on track is why the 750SFC first adopted that colour for Laverda – the pit crew would always be able to tell when their 1000cc triple was approaching the finish line on every lap, since nothing else in the race would ever sound like a Laverda triple in action!

First, though, after pulling up the ignition switch on the top right of the tacho, I’d had to fire up the motor on the electric starter via the button mounted above the right clipon, which you must reach over to push with your left thumb so as to catch the throttle as it fires up – sometimes, after several turns. Select first gear by pressing down with your toe on the right-foot gearlever, and let the lusty three-cylinder motor pull you away seamlessly from rest.

If you wish you can change up by kicking the very Italian rocking pedal gearshift lever with your heel, but it takes some getting used to, especially as the gearchange feels rather rubbery and not too precise, though I never missed a gear. But first gear is very long, which made it OK to use in the Varano chicanes, as it probably would have been at a tight hairpin like La Source at Spa, where the extra engine braking would also have been helpful to stop such a heavy bike weighing over 220kg, with a full load of fuel.

“It’s very measured in the way it builds revs – this is a long-legged bike which seems strong and robust, happy to surf the relatively meaty midrange torque curve, you must be ready to counter the patch of roughness just under 4,000rpm.”

I had much less than half that in the tank when I rode it, but the cast iron Brembo brakes surprisingly had less bite that I expected – and since I’ve been using a similar set for the past 40+ years on my Ducati 750SS, I know how well they should work! Mine are gripped by Lockheed calipers, and that’s probably the reason, since Brembo’s two-piston black calipers were never as effective. This made me glad I had the extra help of the engine braking in slowing down, without buzzing the engine on the overrun. Using the rear brake hard helped stop the Laverda triple adequately well without chattering the rear wheel, as it will do on my desmo V-twin if I use it too forcefully.

But as against that slight disappointment, the 3C Laverda’s handling was a pleasant surprise, and especially the way it steered. I’d been expecting it to be a big, heavy old thing that needed a good tug to lift from side to side in Varano’s quartet of chicanes, and it did indeed need physical strength to do so in the slowest of these – this is not a GP racer! But the chosen front end geometry allowed it to tip into corners easily and controllably, both hard on the brakes, and at a faster pace – the problem came in lifting it up and over for the exit, even with a relatively light fuel load. The second gear chicane on the far side of the track was a good tester of its agility at higher speed, and there the Laverda passed with flying colours – it just found its way almost on autopilot, without undue exertion.

“The chosen front end geometry allowed it to tip into corners easily and controllably, both hard on the brakes, and at a faster pace – the problem came in lifting it up and over for the exit….”

Mind you, that came with the conservative riding style that was the benchmark of Endurance racing back then, when one set of tyres would last an entire 24-hour race. “Even Marco didn’t hang off the side like he did later on!” said Roberto Gallina. “Endurance racing then was about getting comfortable for the long spell and conserving your energy – remember we only had two riders per team, not three or even more like they have nowadays.”

So the plushly padded seat on the Laverda was your throne for the long haul which, coupled with the relatively low footrests denoting a period when the treaded tyres didn’t permit excessive angles of lean, makes you feel wedged in place, unable to move around the bike thanks to the close-coupled riding position. Just get ready to tuck yourself behind the broad fairing and rest your elbows on the wide, flat fuel tank with its twin filler caps as you tackle those long straights at Spa or Mugello, while that so-distinctive engine beats away seemingly unburstably beneath you.

“The 3C Spaceframe must have been a fine ride for a 24h marathon on big circuits by the standards of the era, especially in damp conditions where the good feedback from the Ceriani suspension would have added confidence.”

The 3C 1000 Laverda Spaceframe must have been a fine ride for a 24-hour marathon on big circuits by the standards of the era, especially in damp conditions where the good feedback from the Ceriani suspension would have given added confidence, coupled with the friendly, flexible delivery from the three-cylinder engine. Too bad there were those pesky, potent four-cylinder devices developed by Honda-san and his rivals that were faster in a straight line. But that was only until it rained, when the needle of rideability swing in favour of the Italian triples – as it did at Spa-Francorchamps in 1975……

1975 Laverda 3C 1000 Endurance Racer Specifications

ENGINE: Air-cooled DOHC three-cylinder in-line four-stroke with 180° crankshaft, chain camshaft drive, and two valves per cylinder (40mm inlet/35.5mm exhaust), 75 x 74mm bore x stroke, Bosch BTZ electronic CDI with belt-driven alternator, 3 x 36mm Dell’Orto PHB, 5-speed close-ratio, 13-plate oil-bath clutch with triplex chain primary drive and duplex chain final drive.

CHASSIS: Chrome-moly tubular steel open-cradle spaceframe with engine as fully-stressed member, 38mm Ceriani telescopic fork adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping (f) Tubular steel swingarm with 2 x Ceriani shocks (r) 2 x 280mm Brembo cast iron discs with two-piston Brembo calipers (f) 1 x 280mm Brembo cast iron discs with two-piston Brembo caliper (R) 110/80-18 Avon AM22 on 2.50 in. FLAM cast aluminium wheel (F) 120/60-18 Avon AM23 on 3.00 in. FLAM cast aluminium wheel (r). 1486mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 96hp@8,500rpm (at gearbox), 238km/h top speed (Spa-Francorchamps 1975), 200.5kg with oil/no fuel, split 50/50.

Owner: Collezione Famiglia Laverda, Breganze (VI), Italy

1975 Laverda 3C 1000 Endurance Racer Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.