Undoubtedly, one of the most iconic motorcycles from Harley-Davidson's road racing history, Cathcart took the XR1000R Lucifer's Hammer for a spin 40-years ago this year... Photos: Bill Petro

2023 sees Harley-Davidson celebrating its 120th birthday – but the 81st running of the Daytona 200 on March 11 will also mark the 40th anniversary of one of the company’s most legendary victories ever on-board the Lucifer’s Hammer at the banked Florida Speedway…

March 11 will mark the 40th anniversary of one of the Motor Company’s most legendary victories ever on-board a XR1000R at the banked Florida Speedway…

Lucifer’s Hammer, says an old Irish legend, was a comet sent by the Devil to destroy a village which had been invaded by foreigners so evil they made Lucifer himself jealous. How apt that the bike bearing the hellfire red and black colours of the American Harley-Davidson factory, which upended the Italian mafia’s domination of the AMA’s Battle of the Twins series in 1983, should have been so named. Christened by the wife of legendary race manager, Dick O’Brien, long-time chief of the Milwaukee firm’s Racing Department which had brought so much success to America’s Finest down the years.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

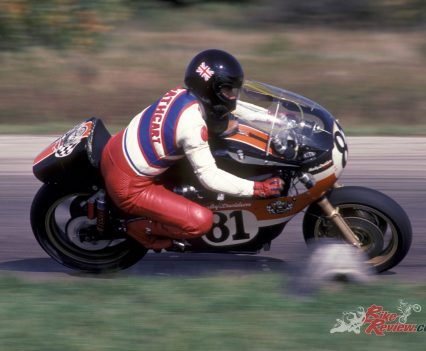

The first Milwaukee-built V-twin to carry the factory’s colours at Daytona in ten years, Lucifer’s Hammer scored a convincing victory on its debut appearance there in March 1983 in the hands of dirt-track great Jay Springsteen, a legend in his own lifetime as the winner of more AMA dirt track Nationals than anyone else ever, enroute to three Grand National titles by the age of 25.

Springer was a God-given expert road racer, if only at that stage with just four such races under his belt in the previous seven years. He dominated the Cycle Week ’73 50-miler, defeating a field including the Ducati-mounted reigning TT F2 World champion Tony Rutter and defending AMA BoTT champion Jimmy Adamo by 24 seconds, easing up.

Springer was a God-given expert road racer, if only at that stage with just four such races under his belt in the previous seven years…

A week later at Talladega, Springer was half a minute in front of Adamo en route to a certain repeat victory, when he unloaded on someone else’s oil on the final lap, while on his next ride aboard the bike at Elkhart Lake, the engine seized when a camshaft bearing broke up, sending him crashing into retirement again.

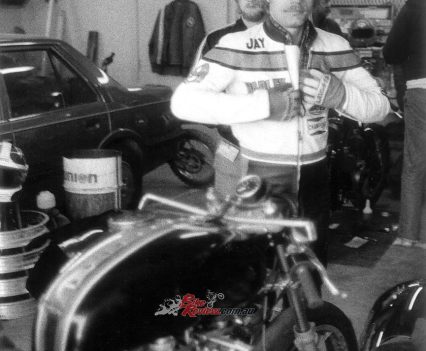

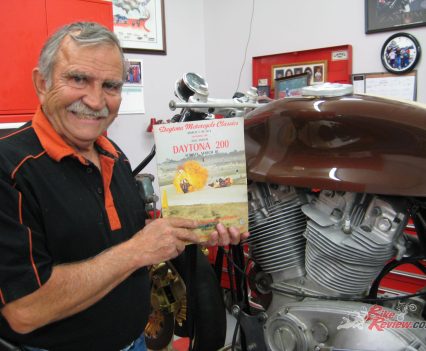

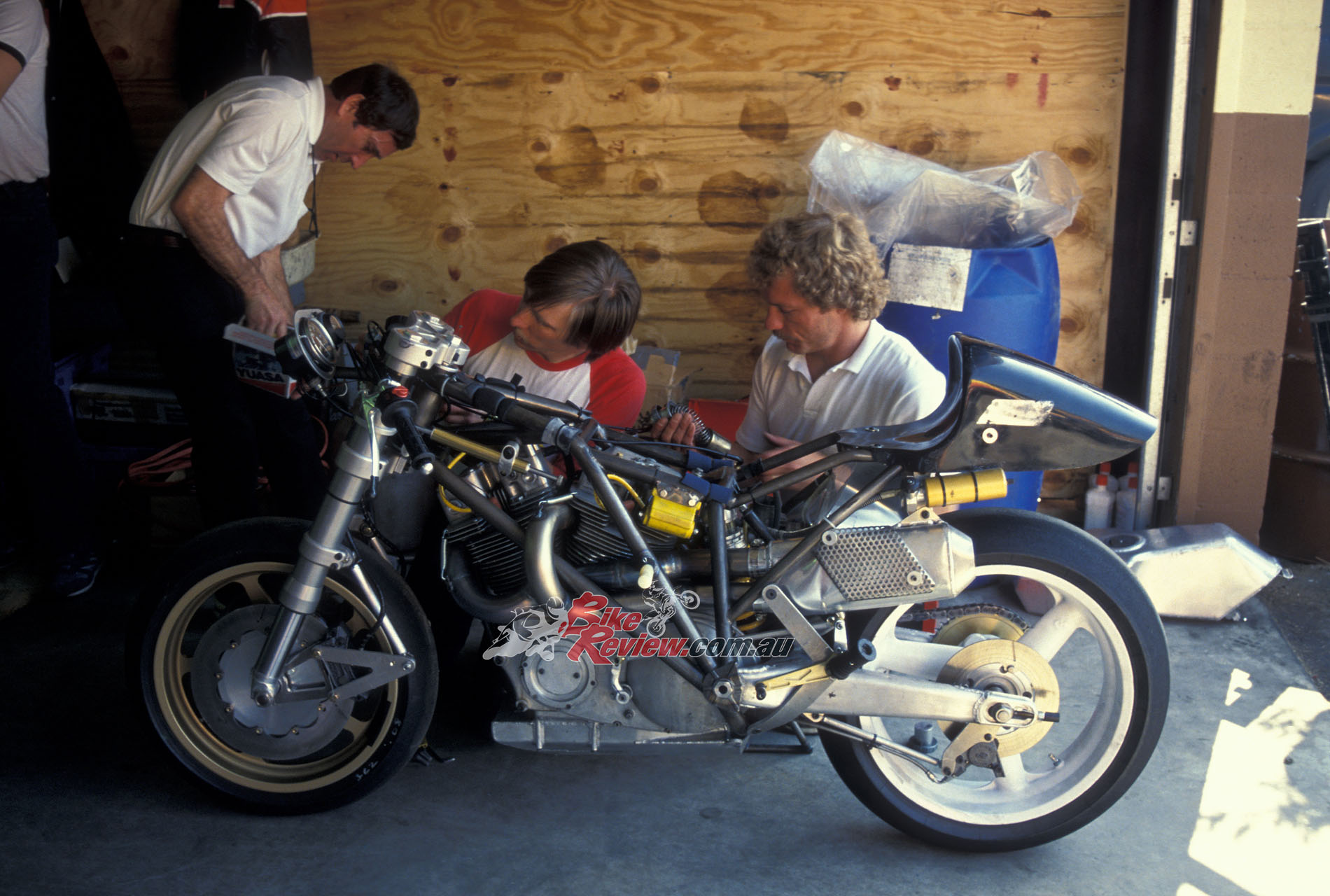

Mert Lawwill and Jay Springsteen working on the XR1000R at Daytona in 1988. He was a natural road-rider but his dirt track career took priority.,

But at Loudoun in June, Jay rode Lucifer to an excellent 13th place overall in the AMA National Formula 1 race against the Honda, Suzuki and Kawasaki fours and all the TZ750 Yamahas, earning valuable Grand National title points into the bargain in those days when road racing and dirt track events all contributed to your points score.

Although Jay’s oval-track commitments precluded his racing the bike ever again thereafter, Dave Emde took it over to register a couple of second places behind Adamo that summer, before Carolina dirt-tracker Gene Church was entrusted with it for the final race of the season at Daytona in October, which he won after a thrilling three-way Battle with the Ducati’s of Adamo and Joey Mills. In bookending the season with another Daytona victory, Lucifer’s Hammer had routed the foreigners again!

Gene Church was entrusted with it for the final race of the season at Daytona in October, which he won after a thrilling three-way Battle with the Ducati’s of Adamo and Joey Mills.

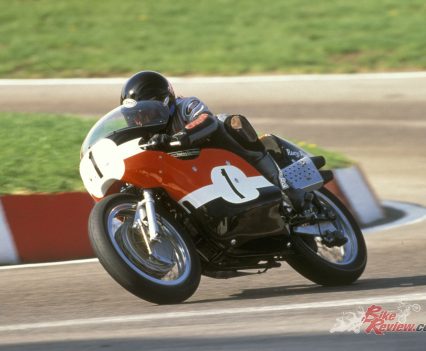

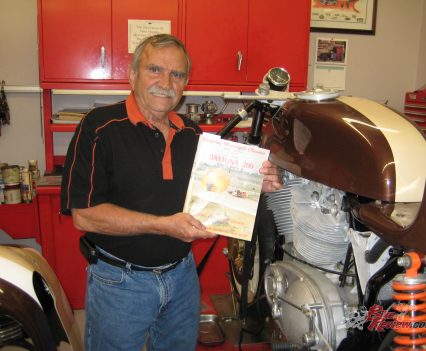

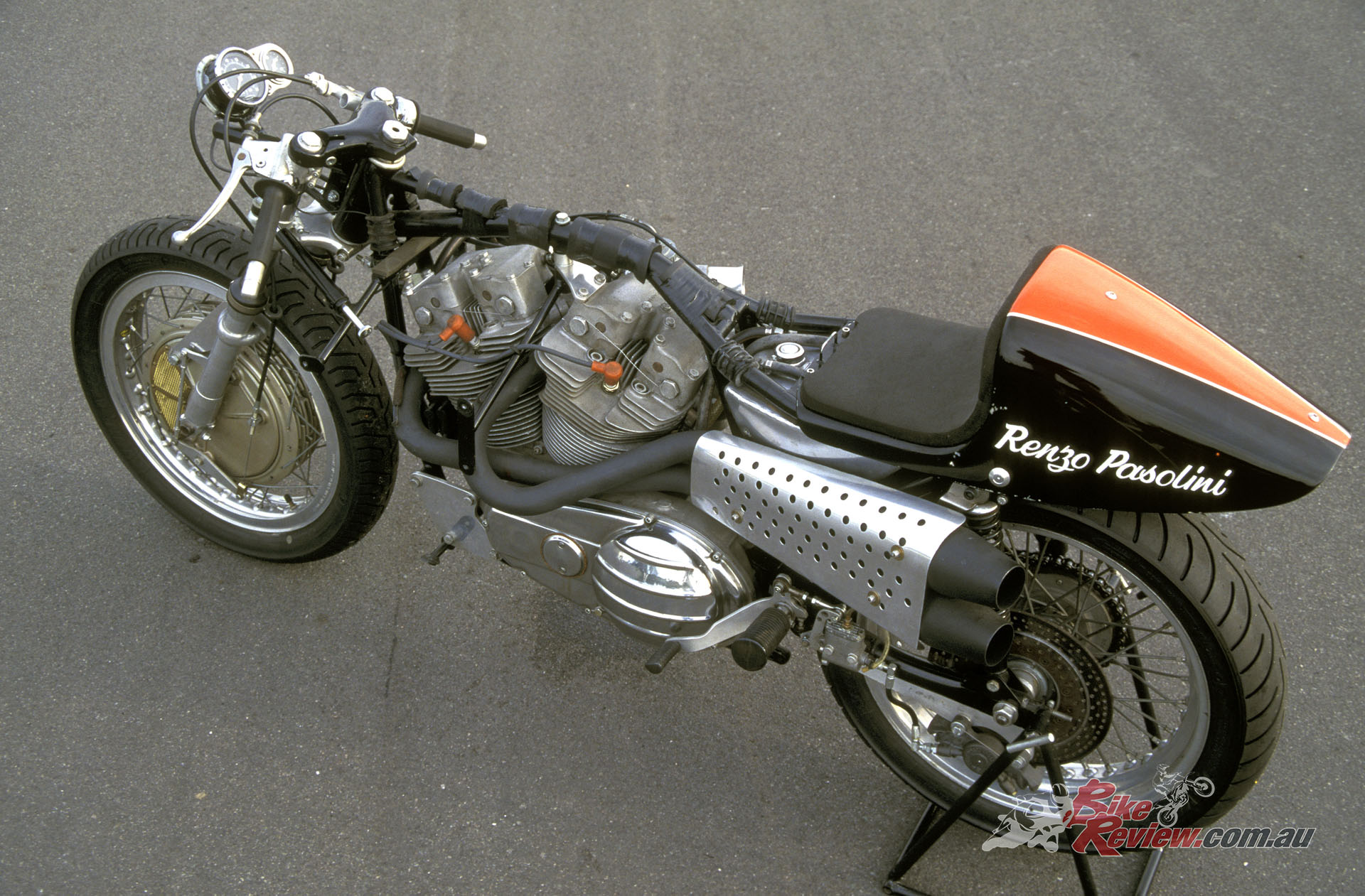

As a hardened protagonist in the Battle of the Twins, racing in the class on both sides of the Atlantic, the chance for me to ride this factory Harley at the end of its debut ’83 season was a double treat. For although a member of the desmo V-twin Italian Mob struggling to keep pace with the pushrod H-D in AMA Nationals, I’d already acquired and restored the 1972 ex-Renzo Pasolini factory Harley XR750-TT road racer that I owned and raced in European Historic events for more than two decades: it now resides in the Barber Museum in Alabama.

“As a hardened protagonist in the Battle of the Twins, racing in the class on both sides of the Atlantic, the chance for me to ride this factory Harley at the end of its debut ’83 season”…

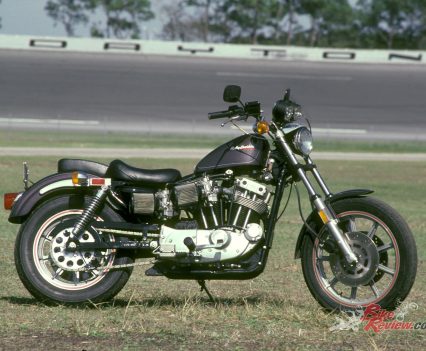

Harley’s participation in the new AMA National series which had kicked off in 1982 really put the BoTT on the map, but the class also helped the factory to publicise its new XR1000 street bike, a distant descendant of the legendary XR750 and together with it the progenitor of the factory BoTT racer.

When I met up with Lucifer’s Hammer at the picturesque Blackhawk Farms track on the Illinois-Wisconsin state line the week after Church’s ’83 season-ending Daytona win, also on hand was engine builder Don Habermehl, who together with designer Peter Zylstra plus chassis specialist (four-time AMA champion) Carroll Resweber, was one of the select team inside the H-D race shop which, under Dick O’Brien’s guidance, was responsible for creating both road and race versions of the XR1000.

I’d already got to know O.B. when trying to track down one of the streamlined Wixom fairings for my XR750-TT. A nominal ten bucks bought me one with Mark Brelsford’s race number on it – but it was only later that I discovered that Dick had effectively donated it from his own parts store, glad that someone in a faraway land appreciated what his race shop guys had achieved. Because it was he who had bought Brelsford’s former race bike and attendant parts – which is how the whole Lucifer’s Hammer project came about.

Cathcart was no stranger to the thumping v-twin of a Harley road-racer, having raced the XR750-TT years prior…

For after the management buyout at Harley, now free of the AMF conglomerate which had controlled the company’s fortunes for so long, its directors had decided on an official return to road racing with a full-blown contender for overall honours in the BoTT.

Dick O’Brien had campaigned for the budget to go road racing again…

Dick O’Brien had campaigned for the budget to go road racing again, and with the new XR1000 streetbike’s introduction heralding a performance-orientated tinge to Harley’s range, the board gave him a percentage of what he’d asked for and kept their fingers crossed that O.B. could do the job against the by now increasingly swift Ducati’s, Yamahas, Guzzis and the Big D Triumph.

The XR1000R’s success is even more spectacular when you find out that Dick only found out about H-D’s return to road racing 60 days prior.

Only one drawback: O’Brien got just 60 days’ notice of Harley’s return to road racing, before the start of qualifying at Daytona! 60 days to build a race bike, test it, incorporate any needed mods, and get to Florida ready to race – and win. Such a compressed time frame would tax even the resources of the mighty Japanese, but with the H-D race shop now reduced in size to a slim six people plus O’Brien himself, whose main priority was retention of the crucial dirt-track focused AMA National title, it seemed a tall order indeed.

“O’Brien got just 60 days’ notice of Harley’s return to road racing, before the start of qualifying at Daytona! 60 days to build a race bike, test it and incorporate any needed mods…”

“We had to square off a few turns,” Dick had admitted as we’d stood in the Florida sunshine earlier that year admiring Lucifer’s Hammer on the verge of making its racetrack debut in practice for the Daytona BoTT. “We had so little time to produce a race version of the XR1000 that we’ve had to be a lot less radical than I’d have liked. Fortunately, we did all the development work on the XR1000 street bike actually in the race shop, so we had all the basic data. It was just a matter of going on to the next stage – and the one after that!”

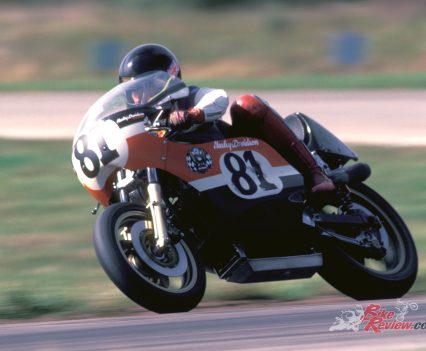

The lack of available time for the project meant the bike which debuted at Daytona was a true Modern Classic – an updated version of the XR750-TT with which Harley had last appeared officially in road racing a decade earlier, before retiring outclassed by the new generation two-strokes. Yet there was nothing obsolete about the way in which Jay Springsteen trounced the opposition at Daytona in his first road race for five years.

Fastest in practice, easy winner of his heat race, and quickest through the speed traps on the banking at 158mph into a 7mph head wind – 6mph ahead of his nearest rival, another Harley ridden by Florida truck driver Hal Coleman – Springsteen dominated the BoTT 50-miler. It was a comprehensive win on H-D’s return to road racing after a decade, which vindicated O’Brien’s belief in the bike’s potential.

For Springsteen’s mount was itself derived from a very historic motorcycle, for the chassis and much of the running gear on Lucifer’s Hammer belonged to the last XR750-TT road racer ridden by the late, great Cal Rayborn, before his tragic death riding a Japanese two-stroke in New Zealand early in 1973. The bike had then instead been assigned to reigning AMA National champion and new Harley team leader Mark Brelsford for the Daytona 200 in March that year – only for Mark to hit a slower rider in the fast Turn 3 infield kink, sending the Harley erupting into a spectacular fireball captured on film by a local photographer in a shot that’s rightly become one of the most famous race pictures in the world.

Brelsford hit a slower rider in the fast Turn 3 infield kink at Daytona on the XR750-TT, sending the Harley erupting into a spectacular fireball captured on film by a local photographer.

The resultant charred remains were rebuilt, but with Harley retiring from road racing later that year, O’Brien actually bought the bike from the factory himself. But a decade later, with the rest of the dozen or so XR750-TT road racers ever built by then in private hands, and the pressure of time to get on the Daytona BoTT grid an important factor, O.B. decided to update his own bike’s chassis, and worry about constructing a new one later should the need arise.

By the time the XR1000R was ready to race, the frame was a decade old. Carroll Resweber added a triangulated backbone brace, stiffened up the headstock and swingarm pivots with extensive bracing.

The result, like so many BoTT contenders of the time, was a fascinating mix of old and new. To update the ten year-old tubular steel race frame for use with slick tyres, Carroll Resweber added a triangulated backbone brace, stiffened up the headstock and swingarm pivots with extensive bracing, and fabricated an all-new box-section steel swingarm.

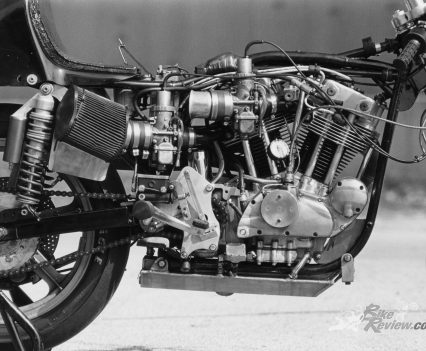

40mm Forcella Italia forks with adjustable damping and magnesium sliders were matched to fabricated H-D triple-clamps and a Kawasaki steering damper, with a pair of Fox gas shocks at the rear and Campagnolo magalloy wheels. These were originally 18-inch items front and rear, but for Church’s Daytona outing a 16-inch front was tried for the first time, and was still fitted when I rode the bike at Blackhawk. Two 300mm floating Brembo discs were used up front, with a fixed 240mm rear, with Brembo gold calipers all round. Wheelbase was a trim 56in/1420mm with the 16-inch front wheel.

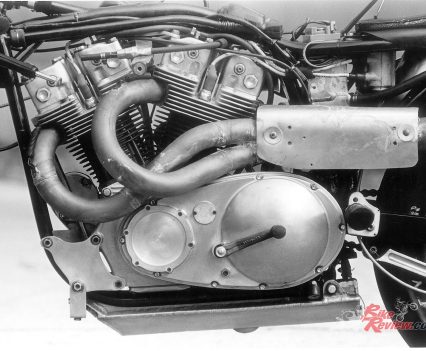

While Resweber was building up the chassis, Don Habermehl assembled a motor which similarly combined something old, something new – and something trick. Using XR750 crankcases with an oversize left-hand main bearing, cast-iron Sportster cylinders coupled with XR aluminium heads and rocker boxes, special flywheels made from XR forgings but with the longer Sportster stroke, an XR caged roller-bearing crankpin and short conrods, he built a motor that immediately produced 90bhp quite readily, compared to the 70bhp of the XR1000 streetbike.

Then came the hard work, wringing a couple more horsepower here, another one there, all with the aid of lengthy, patient dyno work experimenting with different exhausts, ignition timing, cam profiles and carburation. More tuning was carried out on the exhaust system, which differed quite a bit from the old XR750 road racers. Noise regulations of 115 dBa introduced in the decade since Rayborn’s day were met via longer megaphones coned and packed internally with wire wool. The bike still sounded just as great as an unsilenced XR, though – just that the rolling thunder seemed closer to the horizon.

This wild machine made a whopping 106bhp@7,500rpm (at gearbox), a rocketship for the era. Have a look at the tiny 16in front wheel, still fitted when Alan rode the bike.

Retarding the ignition to only 17° of advance in combination with reworked and carefully matched twin-plug cylinder-heads ported by O’Brien’s long-time Los Angeles-based collaborator Jerry Branch, yielded the greatest power increase, and combined with 42mm smoothbore Mikunis and some experimental cams that according to Don Habermehl had been ’laying around the race shop for quite some time’, eventually produced 106bhp@7,500rpm. Lowering the rev limit a little in the interests of reliability meant that when I rode it Lucifer was delivering an honest 104bhp@7,000rpm at the gearbox, running 10.5:1 compression using 110 octane Union 76 race gas. Not bad for an iron-barrelled air-cooled pushrod twin!

Starting Lucifer up from cold on an initially crisp 13°C Midwest fall morning required patience and care. The two quarts (1.9L) of R40 castor oil lived in a fabricated oil tank bolted to the underside of the crankcases, and incorporating a flywheel scraper to improve scavenging by employing a gravity drain to assist Harley’s conventional timed breather. It was a sort-of semi-dry sumped system, but you had to get the oil good and warm before moving off, and because of the complex lubrication the engine had be warmed up slowly and carefully.

I rode the Harley as it had literally come straight from Daytona after Church’s October victory…

This meant a plentiful supply of batteries was called for, because the total-loss system feeding the twin Accel coils wasn’t good for much more than 35-40 minutes before the engine started misfiring. “If we run a 45-minute race we’re in trouble,” Don admitted, “so we’re working on an alternator system to get over that.” Hence why we never did get to see Springer and Lucifer together in the Daytona 200, since typical BoTT Nationals rarely exceeded 50-mile sprints.

I rode the Harley as it had literally come straight from Daytona after Church’s October victory, and because of the constant blowing sand at the Florida Speedway, hefty K&N airfilters were fitted to the bike just like on Springer’s miler, with the rear one flattened to allow the rider’s knee to be tucked in. Gearing was initially way off for the tighter, twistier, Blackhawk Farms track, but the couple of laps it took me to figure this out also revealed the XR’s trump card, its meaty reserves of bottom-end torque and mile-wide power-band – it was a tractor that could outrun an Italian stallion.

It seemed irrelevant what gear I threw at it – just as well, since there were only four – or how many revs I used exiting a turn, since the powerful, smooth-running motor pulled strongly away from down low. Smooth? A Harley? Yessir – I was surprised, too. 45° V-twins don’t have to shake, rattle and roll if they’ve had the benefit of the Harley race shop’s magic wand. There was no real sense of vibration, just a strong, hard push, rather than kick-in-the-back power, rushing you unhurriedly but deceptively fast to the next turn.

“The powerful, smooth-running motor pulled strongly away from down low. Smooth? A Harley? Yessir – I was surprised, too…”

Adding five whole teeth to the rear sprocket for a second, longer, session made all the difference to the gearing, and now I was beginning to feel at home on the bike. The riding position was OK, albeit really meant for someone shorter-legged than me, but the oversize XR750 fuel tank (as used for 200-mile races a decade earlier) fitted snugly into my chest, with its scalloped sides providing good leverage to push the Harley into long, sweeping turns while crouching flat beneath the wide, all-enveloping screen. This fairing was a Wixom-designed XR750 one, too, with aluminium wing extensions for the big screen.

“The riding position was OK, albeit really meant for someone shorter-legged than me, but the oversize XR750 fuel tank (as used for 200-mile races a decade earlier) fitted snugly into my chest.”

Despite the considerable suction effect of the big carbs, the throttle action felt firm but smooth, and while the quite positive left-foot gearchange was nothing like as clunky as the one on my oId XR750-TT, the widely spaced dogs and large gears meant it needed a firm foot on the pedal, with a very mechanical feel to each shift. But with only four speeds, and first gear largely redundant, you didn’t have to shift that often, thanks to Lucifer’s broad spread of power and especially, torque. The transmission still used a triplex primary chain – the team had designed a belt drive conversion, but found it’d mean spinning the XR750 road racing transmission too fast, and thus risk overloading the gears accordingly. The gearshift had a very short throw, though.

The pushrod motor was super-responsive, pulling strongly from as low as 2,000rpm before really lighting up at exactly 4,000rpm, pulling to peak revs of 7,000rpm without any sign of a hiccup through the 2-1 exhaust. But it was always controllable power – cracking open the throttle didn’t unhook the rear tyre as it had with Britain’s champion Twin, Bob Smith’s RGB-Weslake that I’d ridden just a couple of weeks earlier. That had a superior power output and reduced weight – the iron-barrelled Lucifer scaled the same 335lb/153kg with oil but no fuel, as a Rayborn-era XR750-TT with its all-alloy engine – but a much less manageable powerband, as well as horrific top-end vibration, in best BritBike parallel-twin mode.

“You didn’t have to shift that often, thanks to Lucifer’s broad spread of power and especially, torque.”

What did unhook Lucifer’s rear tyre was the Goodyear slick’s ultra-hard compound, designed to run at top speed for extended periods on Daytona’s bankings in 16°C warmer weather. It never even came close to heating up properly at Blackhawk Farms, and I had some lurid slides as a result. Even after 35 laps of the 1.8 mile track with its pretty long front straight, the centre of each tyre was barely warm, despite dropping the pressures by 4 psi.

It seemed strange Goodyear tyres were used on the bike, since the US tyre company by then no longer made motorcycle road tyres, and so all street Harleys were by then fitted with US-made Dunlops as OE. However, Dunlop had declined to equip any bikes for AMA racing other than the factory Yamahas of Roberts and Lawson at Daytona, hence H-D’s switch to Goodyears. “We wanted to use the same make as on our road bikes for obvious reasons,” said a puzzled O’Brien, “but Dunlop said they weren’t interested in supplying anyone except factory teams. Aren’t we one of those, too?” Seems the then-British owned tyre manufacturer missed an easy opportunity of claiming another Daytona race win, and cementing its relationship with America’s Finest.

“The pushrod motor was super-responsive, pulling strongly from as low as 2,000rpm before really lighting up at exactly 4,000rpm, pulling to peak revs of 7,000rpm without any sign of a hiccup through the 2-1 exhaust.”

The Brembo brakes were simply fabulous though, even disregarding the considerable engine braking delivered by from the long stroke 81 x 96.8mm motor (compared to the XR750’s 79.4 x 75.7 mm), which made me take care not to use too many revs on the overrun in those pre-slipper clutch days – else you’d, ahem, chatter the rear wheel all the way into the apex, while frantically fanning the clutch lever to try to get it stopped before running out of road. Phew! Harley had been working on an air anti-dive system for the FI front fork, and had hoped to have it ready for me to test, but ran out of time.

Personally, I didn’t think it was needed, since the good damping delivered by the Italian fork even when all three brakes were being squeezed tight ensured the suspension didn’t freeze up. The Brembos hauled the Harley down from high speed very quickly, so factoring in the engine braking helped explain how Springer had been able to dazzle other riders (me included!) at Daytona with his ability to go barrelling past us into the turns so deep with both wheels drifting – very impressive when viewed from close up behind, I have to say. Maybe that’s really why Harley used such hard-compound rubber – just to make those dirt-tracking good ‘ol boys feel right at home!

So far, so great – but now for the one disappointment in riding Lucifer’s Hammer. The handling in slower turns felt decidedly odd, which wasn’t the problem I’d expected after talking to Carroll Resweber at Daytona, when he’d lamented the difficulties of beefing up a ten-year old chassis to cope with slick tyre technology: “All you’re doing is shifting the forces somewhere else,” he’d said, shaking his head. “They gotta work themselves out somehow – so all you’re doing is putting the hinge in the middle, rather than up front or out back! Once Jay really starts switching ‘er on, we may have to go to a new frame.”

Three years on, they’d do just that with the Buell-chassised Lucifer II, but at the time of my test that hadn’t been considered necessary, and the hard tyres prevented me finding out exactly where the hinge was located right then. Instead, the problem I experienced was a strange feeling of instability entering a turn, as if the bike were too top heavy and wanted to tip over suddenly into the apex, rather than lay into it more controllably. I reckon this was caused by the newly-fitted 16-inch front tyre, which really didn’t suit the bike that much – the chassis wasn’t designed for it, and I don’t reckon the resultant front-end geometry worked.

Lucifer definitely didn’t like being flicked from side to side on a trailing throttle, as on Blackhawk’s Turns 2 & 3, before the heavy braking for Turn 4, where the front-end began chattering even with the steering damper cranked well up. Then when I got to Turn 4 the old bugbear of 16-inch fronts became apparent, when the Harley sat up under hard braking and tried to understeer straight on into the kitty litter. Then, just when I’d finally persuaded it to lean over into the turn, it just sort of suddenly flopped on its side rather unpredictably, without the same kind of progression I’d get on my own XR750-TT using an unbraced, but better handling, version of the same frame fitted with an 18in Avon treaded front tyre. 16-inch wheels are all very well if the chassis’ designed around them – Honda had already proved that with their VF750 road bike.

“Lucifer definitely didn’t like being flicked from side to side on a trailing throttle, as on Blackhawk’s Turns 2 & 3, before the heavy braking for Turn 4.”

But sticking a smaller diameter front wheel on a bike designed for an 18-incher (and retaining the 18-inch wheel at the rear) may give quicker steering response, plus a fatter footprint which lets you run a wider rear tyre, but it can bring associated problems in its wake, because you’re upsetting the whole balance of the chassis. I was sure that’s what had happened with Lucifer, because I couldn’t believe Springer rode the bike so hard at Loudoun especially – a tight, twisty track like Blackhawk – with it handling like that. If Church’s Daytona outing had been the only test so far of that new configuration, most probably that was indeed the reason, because the Florida Speedway back then didn’t make such great demands on a bike’s handling as a road circuit like Loudoun or Blackhawk. Better I’d have thought to try to lower the whole bike, which was definitely pretty tall by modern standards, and that might have required a new chassis, as Resweber intimated.

Almost everything on this factory racebike was a specially made one-off part, created especially for this motorcycle by true craftsmen with one intent: winning races…

Hard tyres and iffy handling notwithstanding, my overwhelming impression after a day in the company of Lucifer’s Hammer 40 years ago was of that lovely, smooth, torquey and potent motor, and the excellent brakes. That and all the neat stuff abounding on the bike, from the fabricated oil tank and shapely fuel tank, to the oil pressure gauge plumbed into the crankcase (optimum reading just 4psi when hot!) where the rider can’t see it, but the mechanic can.

Almost everything on this factory racebike was a specially made one-off part, created especially for this motorcycle by true craftsmen with one intent: winning races.

Almost everything on this factory racebike was a specially made one-off part, created especially for this motorcycle by true craftsmen with one intent: winning races. I remember forecasting it’d take quite some doing by the band of foreigners to stop Lucifer’s Hammer doing just that in ’84 – and history proved me right, with Gene Church winning the AMA National BoTT title, as well as both Daytona rounds. Guess the bike lived up to Mrs. OB’s Gaelic legend……

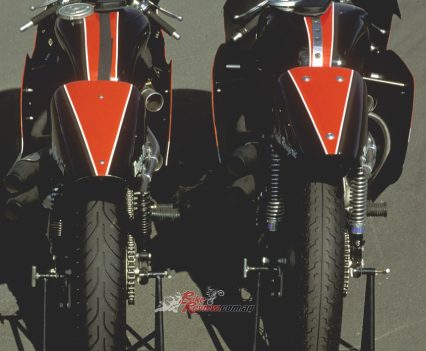

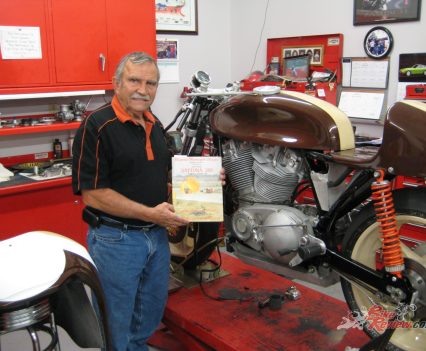

Lucifer’s Hammer went on to be the scourge of all those foreigners in AMA Battle of the Twins racing for quite some time. Gene Church’s debut Daytona victory on the bike in October 1983 came about because, to allow the factory race shop to concentrate on securing continuing dirt-track success, Dick O’Brien had entrusted the factory-built BoTT road racer to North Carolina-based Harley tuner Don Tilley, whose protégé Church was.

The late Don Tilley, legendary H-D dealership owner, ended up restoring and continuing to race the Lucifer’s Hammer…

The quiet young dirt-tracker repaid the confidence shown in him by dominating the AMA National series for the next three years on the bike sponsored by the newly-formed HOG/Harley Owners Group, winning again at Daytona in the 1984 Cycle Week season-opener before going on to wrest the AMA title from two-time champion Jimmy Adamo on the Reno Leoni Ducati, via further race victories at Sears Point and Mid-Ohio.

Church won four races during the season against Adamo’s two, to score a hat trick of AMA title victories on a bike which Don Tilley had carefully developed to be consistently fast…

The following year, 1985, Church really hit his stride on a bike by now painted chocolate and cream rather than H-D’s traditional orange/red and black, winning five races including yet another Daytona victory en route to a second straight title, with Adamo runner-up again. With the Castiglioni family now in charge of Ducati, former 500cc World champion Marco Lucchinelli appeared at Daytona in March 1986 to narrowly defeat Church on Lucifer’s Hammer with a factory 750 F1 desmo V-twin racer, on which he won again at Laguna Seca later that year. But Church won four races during the season against Adamo’s two, to score a hat trick of AMA title victories on a bike which Don Tilley had carefully developed to be consistently fast, yet reliable, passing through the Daytona speed traps at 170 mph – fast going for an air-cooled pushrod V-twin.

Gene Church, Daytona 1984. The Lucifer’s Hammer now a new colour scheme, Tilley name on the rear faring.

At the end of that season the twin-shock Lucifer’s Hammer was retired to the factory museum in favour of an all-new Buell-framed bike for 1987, based on the monoshock RR1000 streetbike with its Uniplanar engine mounts. But Lucifer II, as the bike was inevitably dubbed, took time to develop, not helped by Gene Church breaking his collarbone in a Daytona crash, leaving future dirt-track legend Scott Parker to take the new bike to an encouraging third place in its race debut. Another future dirt-track great, Chris Carr, also rode the bike to fifth place at Memphis, a track with a very long front straight where the XR1000R Harley motor’s impressive speed could make itself felt.

But these results had more to do with Tilley’s engine tuning skills than anything else, and Harley-Davidson went from AMA BoTT champion to also-ran, with Lucifer II making its final appearance at Laguna Seca in 1988, where Church finished 13th. The original was still the best…..

1983 Harley-Davidson XR1000R Lucifer’s Hammer Specifications

1983 Harley-Davidson XR1000R Lucifer’s Hammer Specifications

ENGINE: Air-cooled pushrod ohv 45-degree V-twin four-stroke with two valves per cylinder, 998cc, 81mm x 96.8mm bore & stroke, Dual coil ignition with total-loss 12v battery, 2 x 42mm Mikuni smoothbore, four-speed gearbox, triplex chain primary drive with multiplate oil-bath clutch.

CHASSIS: Tubular steel single-loop backbone with triangulated sub-frame and duplex engine cradle, 40mm Forcella Italia telescopic forks (f) Box-section steel swingarm with 2 x Fox gas shocks (r) 2 x 300mm Brembo discs with two-piston Brembo calipers (f) 1 x 240mm Brembo disc with two-piston Brembo caliper (R) 22.5 x 6.5-16 Goodyear slick on 3.50 in. Campagnolo magalloy wheel (F) 26.5 x 8.0-18 Goodyear slick on 5.00 in. Campagnolo magalloy wheel (r). 1420mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 104bhp@7,000rpm (at gearbox), 251km/h into 11km/h headwind (Daytona 1983), 153kg with oil, no fuel.

Owner: Harley-Davidson Motor Company, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

1983 Harley-Davidson XR1000R Racer Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.