Yamaha returned to the top of 500GP racing in 2000, a position it had forfeited for years of Doohan-inspired Honda dominance. AC rides the YZR500 that did it... Photos: Gold & Goose

Not since 1992, and the last of Wayne Rainey’s hat-trick of World titles, had the Japanese company with the tuning forks badge ruled the roost in Grand Prix racing’s premier class. In 2000, Sir Al had the opportunity to test the YZR500 that changed all of that…

Yamaha took the Manufacturers World Championship from Honda in the final race of the season in 2000.

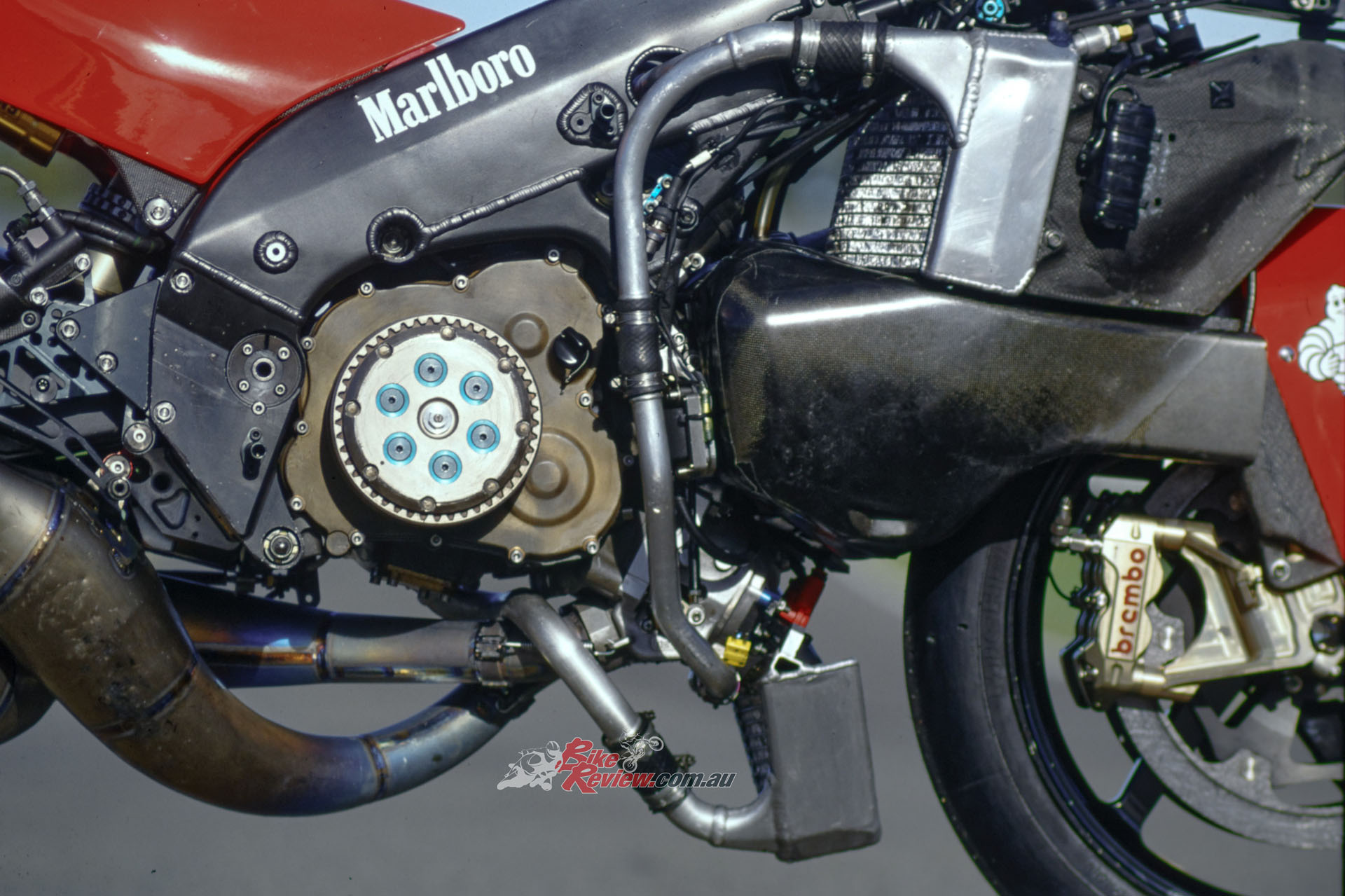

Thanks to a succession of solid performances by Yamaha’s quartet of top ten points scorers in 500GP racing’s penultimate season, it scooped the Manufacturers World Championship from Honda’s grasp in the final race of the season at Phillip Island. In fact, you could say Yamaha won the title by just 0.182 sec. – because that was Australian 500GP victor Max Biaggi’s race-winning margin over Capirossi’s Honda on his Marlboro-sponsored YZR500, in the thrilling finale to a gripping season.

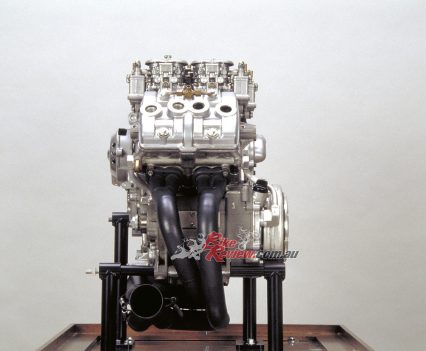

Next week we have Alan’s interview with Ichiroh Yoda and a feature on the single crank Yamaha 500.

The 2000 Season

Had the positions been reversed, Honda would have retained its World crown – but as it was it came away with nothing, and Yamaha took over at the top. Biaggi, McCoy, Checa and Abe shared six wins and 17 rostrum places between them in 2000, the same number of victories as their Honda-mounted rivals, and two more than the two-man Suzuki team managed, en route to Kenny Roberts Jnr’s 500GP Riders’ World title.

Indeed, at one stage it had even looked as if Yamaha might double-up on 500cc dominance by winning the Riders crown as well, with Biaggi’s teammate Carlos Checa tying for the points lead after six races with eventual champion KR Jr., after four second places had made him the most frequent visitor to the rostrum thus far, and a seemingly reformed character who’d succeeded in shaking off the crasher tag he’d done so much to earn in 1999.

At that stage it seemed as if the two Marlboro Yamaha riders had swapped roles, with Biaggi’s pair of visits to the kitty litter in those first half-dozen races, added to two technical DNFs, leaving him 80 points behind his title-leading teammate at that stage of events.

But then in the second half of the season, they switched around again, with Checa’s first retirement of the season coming when he crashed out of his home GP at Catalunya, followed by a series of lowly finishes as he struggled to rebuild his confidence in a bike he now felt at odds with. Carlos ended the season on a sour note when he crashed again in the Phillip Island finale, winding up sixth in the points table, without a single race win. Meantime, Biaggi had come good on his sister Marlboro Yamaha, winning two races and visiting the rostrum twice more en route to third place in the Championship, after out-scoring every other rider in the final six rounds of the 16-race season.

“Yamaha triumphed in the Manufacturer’s World Championship. Mission accomplished”…

A year of two halves for the Yamaha factory duo, then – one in which they’d been unable to rival the title-chasing consistency of Suzuki’s Roberts and his closest challenger, Honda-mounted Valentino Rossi. But thanks to strength in numbers – and the shipwrecked status of the Repsol-badged element in the Honda camp – Yamaha triumphed in the Manufacturer’s World Championship. Mission accomplished – well, partly at least….

The back story

My chance to test the Marlboro Yamaha YZR500 came a month after the end of the 2000 season on a sunswept Jerez circuit in southern Spain – perhaps in recognition of which, it was Checa’s bike Yamaha brought for me to sample, rather than his Italian teammate’s identical-spec machine, with Carlos himself driving down from Barcelona to be on hand to give firsthand advice.

“I ran into problems with the front end flexing, meaning I lost suspension control under hard braking”…

As the first time since 1993 that I’d ridden a factory 500 Yamaha, it was all the more interesting to compare the 75° twin-crank V4 YZR500 in its latest manifestation, with defending World champion Alex Criville’s NSR500 Honda that I’d splashed around Motegi on just a fortnight before, and the RGV500 Suzuki I’d ridden at Phillip Island the day after the last race of the season. Especially as the Yamaha was, according to the Manufacturers points table, the overall class of the Y2K 500GP grid.

Checa chats

Still, it only got that way almost by default, as Carlos Checa explained. “This year’s bike I ended up racing wasn’t so different from the year before,” he said. “We changed several things in front, and the chassis was a little more flexible, to give more feel from the handling – but its K6 twin-crank motor was pretty much the same. That’s because Yamaha committed a lot of resources to working really hard on the L1 single-crank engine, because they believed this could be a lot better than what we have now.

“That meant they cut down quite a bit on working to improve our present bike – but when we tested the L1 in Brno, it was apparent this wasn’t really so different from what we already had, plus there were the reliability problems you get from a single-crank motor. So then they started focusing on the K6 again – but though I still had a good chance in the World Championship, then I ran into problems with the front end flexing, meaning I lost suspension control under hard braking.

“It was really disappointing the way my season worked out after that – but now they have some new Öhlins forks for 2001 which are 46mm diameter instead of the 43mm ones we used in 2000, and we tested them already and they’re a big improvement. But the main problem after my Barcelona crash was me. Maybe I tried pushing in the race a little too soon – but after that we had a couple of wet races, and already the Yamaha is not so easy to ride in the rain, because of the power delivery, so this made my morale even lower.

“I lost my level of confidence, and this is important on the Yamaha because the chassis is so stiff, and my style is to push on the tyre, under braking on the front and under acceleration on the rear. Max has more of a 250 cornering style, where he keeps up turn speed more, and the engine spec we ended up with towards the end of the season favoured this better than my fiercer riding style. I accept the fact that it’s my responsibility to overcome these problems, but the result of all this was that I lost a lot of confidence in the second half of the season, after starting the year so well.”

Doohan Dominated on the Honda for five decades… 2000 was Yamaha’s year to come back strong, and Suzuki too!

Sir Al steps up!

I had a different kind of crisis to resolve: how to find the confidence to ride a bike producing around 200 bhp at the crank (‘over 180’ bhp at the gearbox, at 12,500rpm) at anything remotely approaching anger on a Jerez track still sprinkled with damp patches left over from the thunderstorms of the day before. Especially when, instead of intermediates, the Marlboro Yamaha guys had the bike shod with the soft-compound Michelin slicks Checa himself always opted for in such conditions, rather than even a hand-cut slick which might shift any residual moisture.

“I don’t like to use intermediates in this situation,” said Carlos. “You just have to convince yourself the tyres will grip, and you’ll find they will. Promise!” Okay – but ‘scuse me while I just wobble round upright for five laps or so and work up to this, on a 200-horsepower missile weighing a scant 132kg half-dry, close on the class weight limit. Especially one that, as you say, does have a very, er, vivid pickup around 10,000rpm, where the entry key to title-winning performance is to be found…..

Straight away the Yamaha felt good to sit on, even if the bodywork wasn’t as aerodynamic as Olivier Jacque’s world champion YZR250 I was also riding that day, and the screen the bike was fitted with (Yamaha’s race team had several different ones they used, depending on the needs of the circuit) wasn’t as tightly protective as what was OK for OJ. But it had a relatively spacious riding position thanks to Checa’s preference for the seat to be located more rewards than on the Biaggi bike, with the footrests further back and the ‘bars more steeply dropped – Max preferred them to be more wide-spread.

Yamaha were very focussed on a single crank 500 early in the season, and slowed development of the twin crank, which is what they ended up using anyway…

The result, though, was a stance that, if it didn’t make the YZR500 feel quite as small and chuckable on my second, dry session as the similar-architecture Suzuki had been, took full advantage of its narrower twin-crank layout compared to the broader, beefier single-crank Honda. It didn’t change direction so easily or hold quite such a tight line as the RGV500, but it was definitely lighter-steering and felt less bulky than the NSR500. That was despite the fact that Carlos also opted for a notably lower rear ride height, which helped give the Yamaha a pretty balanced feel to the chassis setup, but didn’t however compromise its neutral steering.

“I could feel the front suspension was set up pretty stiffly – more so than the similar Öhlins fork on the Roberts Suzuki”.

Of course, that’s by conventional standards – but Señor Checa was a member of the born-again class of rear-wheel steerers, and I’ll gladly admit to being not brave enough to even think about trying to learn how to do this, on a 200 bhp megabike. I could feel the front suspension was set up pretty stiffly – more so than the similar Öhlins fork on the Roberts Suzuki – a reflection of the fact that Checa was more aggressive on the brakes than almost anyone else in GP500 apart from Garry McCoy (and he for sure was in a class of his own!).

Carlos braked very hard and very late into a turn, which explained his bike’s low rear ride height (to minimise weight transfer) and the constant search for an optimum fork setting, since this was the single most important aspect of chassis setup for a rider like this. Mind you – it’s not as if it ends there: “We tried a couple of different types of chassis during the year, with different swingarm locations and designs,” said Carlos, “but we ended up going back to the original one. I like to focus on getting the front suspension set up best, that’s the most important thing for me, but is has to be part of a package.

“So I experiment a lot also with swingarm position and rear spring and suspension link – we have five different types, though I usually work with the same two or three. But for me the balance is most important, between control over the front wheel when braking into the turn, and getting good grip at the rear, and traction on acceleration.

“Tyres play a big part in this, too, of course – I like to use a 17-inch rear like you have here today, because it grips better on the angle and makes the bike steer better, too. But we can’t use it in a race, because it won’t last, so we always race now with a 16.5-inch rear, and Michelin are also working on a 16.5-inch front tyre, which I don’t care for, so you can be glad you don’t have it on the bike here! It chatters the front end too often, and makes the steering too heavy, so I didn’t use it so far in a race.”

“The moment you gassed a V4 500GP bike wide open, was unquestionably the greatest thrill available on two wheels 25 years ago”…

Well – thanks for the lesson in 500GP setup, Carlos – just as well I was taking notes! Now let’s go and put your handiwork into practice aboard your little red bull of a bike with the horns sprouting out of your No.7 race number on the nose of the fairing. Olé!! Well – that was what I felt like shouting to myself as I gassed up the Yamaha out of the last turn before the Jerez pit straight after an exploratory warm-up lap – rider, that is, not tyres! Because riding as the replica Rocketman you were suddenly transformed into the moment you gassed a V4 500GP bike wide open, was unquestionably the greatest thrill available on two wheels 25 years ago – especially when you had at least the illusion of being in control that a refined and responsive package like the YZR500 gave you.

Taming the red bull

The front wheel lofted skywards as you twisted your wrist, while you stood on the footrests and desperately tried to throw as much of your body weight forwards as you possibly could. This was while all the time hoping that the track really was dry enough now to keep the back tyre hooked up, and aiming for where you thought you remembered where it was headed before you found yourself inspecting the upper triple clamp of the Öhlins forks even more closely, after it reared up in your face.

Power delivery was good low down, with the Yamaha pulling cleanly out of a slow turn like Dry Sack from below 7,000 revs, but with a strong, smooth transition into peak power territory above 11,000rpm…

Yet all the time you were trying to will yourself not to chicken out and back off the gas, so as to make the front wheel resume normal contact with terra firma. Doing that meant losing valuable time, momentum – and brownie points with the Yamaha pit crew watching (no doubt with amusement!) from pit wall, as I repeated the sideshow all over again, every time I hit a higher gear on the smooth-action powershifter.

Hang on, though – didn’t I have exactly this same problem exiting the very same turn a year ago, with the ‘99 RGV500 Suzuki that even by my standards had a less aggressive power delivery than the Y2K Yamaha? Yes, I did – and I remember too Suzuki’s Aussie race engineer Warren Willing’s advice then about how to cure a problem that he summarised as ‘very spectacular, but also a waste of time – literally!’ That was to stop shifting gear too soon, when I’d still find myself riding the peak of the V4’s torque curve, and hold the gear so as to fall off the end of it before changing up, much more controllably. OK – let’s try it with the Yamaha and see what happens….

It worked! Power delivery was good low down, with the Yamaha pulling cleanly out of a slow turn like Dry Sack from below 7,000 revs, but with a strong, smooth transition into peak power territory above 11,000 rpm, where peak torque was delivered. From around 8,500 rpm, the engine picked up speed very fast, while I desperately tried to hold on tight, and not get the front end flapping around by being propelled rearwards by that vivid acceleration, while attempting to lever myself forward via the ‘bars.

Distribution of body weight was and still is such a crucial factor in getting the best out of a modern 500GP or World Superbike racer, especially something with as explosive a power delivery as the YZR500 – and it did have a much more sudden pickup from a closed throttle than either of its Honda or Suzuki 500GP rivals. Instead of the bank of 35mm Keihin powerjet flatslides, it felt like you were riding a bike fitted with fuel injection.

Noriyuki Haga’s R7 Superbike I was also riding that day in its early guise had been just about as jerky and brusque in pickup response as the YZR500. Except, it had 20% less power than the two-stroke, which delivered that increased output harder, faster and even less controllably than the four-stroke.

I had a graphic illustration of this one lap when I misjudged my entry speed for Curva Sito Pons, the fast third-gear right hander leading over a slight brow onto the main straight, so backed off to adjust matters – but then foolishly compounded my error by getting back on the throttle again too hard, with the tacho needle parked around the 10,500 rpm mark. Two things happened very fast, while I was leaned hard over on my right knee: I could feel the the rear Michelin start to spin as the extra dollop of torque, and power, hit home – and much to my horror, the front wheel lifted up off the ground as we crested the slight rise, but with the bike still cranked right over.

“I could feel the the rear Michelin start to spin as the extra dollop of torque, and power, hit home – and much to my horror, the front wheel lifted up off the ground as we crested the slight rise, but with the bike still cranked right over”…

I have no idea how I survived such a close encounter with a not-quite highside that was surely all part of life’s rich passion for 500GP megastars like Carlos and Max, but it was a long time since I’d pulled a side-on wheelie like that, and survived – exiting Snetterton’s Russells Bend on Kevin Schwantz’s Pepsi Suzuki back in 1988 was the last time I could recall, and I assure you that once it’s happened to you, this isn’t something you forget easily!

“Distribution of body weight was and still is such a crucial factor in getting the best out of a modern 500GP or World Superbike racer”…

But it spoke volumes for the Michelin rear tyre it’d put up with this kind of abuse, as well as for the Yamaha chassis design and the Öhlins suspension setup, that I didn’t either get high-sided into the stratosphere, or else low-sided into the sandtrap. But it did teach me to be properly respectful of the YZR500’s pretty snatchy pickup that was unexpectedly sharp despite the fact that, unlike the NSR500 Honda ‘screamer’, this was still a more controllable (well, relatively…) big-bang V4 engine format, with all four cylinders firing within around 70 degrees of crankshaft rotation.

“Oh – you felt this, did you?!” said Carlos Checa with a big smile when I told him what had happened. “We know we must remember always to pick the bike up if it’s about to hit 10,000rpm leaned over – otherwise it wheelies big time! If we can’t avoid it, we have to change the gearbox internally to stop this. Glad you experienced this for yourself!” Sure, Carlos – anytime…

Once I’d clocked this, the Yamaha became a refined if razor-edged rocketship: you had to pay attention to the bright red shiftlight mounted on the dash and not change gear when hard on the gas till you saw it flashing in your face at 12,000rpm. In fact, the power didn’t tail off till well over 13,000rpm, so the shiftlight was actually a warning not to change gear wide open until you saw it. Then, when you did, you could think about tapping the quite notchy but relatively precise powershifter lever to hit one gear higher wide open on the throttle – or else holding the gear to save a couple of changes, like hanging on to fourth gear before the right hander…

That’s where I had my moment of truth, and seeing the tacho needle scoot to almost 14,000 revs as you did so without any significant drop in power, before you had to get hard on the brakes. Using that gearshift to change cleanly from second to third gear was a bit of an acquired skill – probably this particular bike needed attention to the setup, because you had to back off the throttle slightly to get it to shift cleanly under hard acceleration, which surely wasn’t right.

“After riding the Checa bike on a technical, twisty circuit like Jerez, I could only agree about the superb handling”…

What was only too right was the quality of said acceleration – and the way the Yamaha chassis put it to the ground. The way it did so made me understand firsthand for the first time the concern of Honda engineers expressed to me when I tested Alex Crivillé’s 1999 title-winning NSR500 one year previously, about how their Yamaha counterparts had succeeded in refining the YZR500 into a bike that was now at least as fast as theirs in a straight line, but handled better. After riding the Checa bike on a technical, twisty circuit like Jerez, I could only agree about the superb handling.

It didn’t steer quite as well as the Suzuki, but was pretty close – and for sure it was more stable, especially under hard braking. Plus it was forgiving when you got out of shape, like on the rough patch of tarmac you had to run over hard on the gas with the rear suspension compressed leading onto the main straight, after you’re congratulating yourself for having avoided another cranked-over wheelie. The handlebars flapped once in your hands, before the incipient speed wobble was strangled at birth by that great chassis. This was always so beautifully balanced, with neutral handling characteristics which meant the Yamaha literally went where you pointed it, even under power.

In fact, there was such little understeer that to begin with, I found myself oversteering towards the inside of turns as I opened the gas to drive out of them, because I was over-compensating for something that didn’t exist! Not something I’ve ever had to cope with before on a GP500, and a mark of the Yamaha’s fabulous chassis setup. Actually, this was a little frustrating, even – because with such a good chassis, it would have been nice to try to dial the front suspension up a little softer, so as to use more corner speed than the Checa settings allowed – hang on, though: that’s Max’s Way….

“Where the Checa Yamaha really excelled was under heavy braking, where it was definitely more stable than any of the other current-generation 500s I’d ridden”…

Where the Checa Yamaha really excelled was under heavy braking, where it was definitely more stable than any of the other current-generation 500s I’d ridden, especially the Suzuki. It made you understand how Garry McCoy could do the things he did with his YZR500… Several times going into Turn One at Jerez I was convinced I’d outbraked myself, only to find I could pick a line and hold it into the tight right hand Turn 1, while still braking deep and hard into the uphill apex – well, by my standards, anyway, if not by Carlos’s!’

This predictability was a big bonus, and came thanks to what felt like much reduced weight transfer, thanks to a combination of the chassis design and the low rear ride height Checa opted for. I didn’t get the back wheel street-sweeping beneath me at the end of the straight like I had on the Suzuki on the same track a year earlier – but the RGV500 derived its agility and nimble steering from a mixture of weight distribution and front end geometry that compromised its behaviour when stopping hard – and the Yamaha didn’t suffer from this.

And although it shared the same superbly powerful Brembo carbon brake package as the Suzuki (and Honda), the YZR500 seemed to have a little more feel and progressivity to its black brakes’ response than the fiercer Suzuki package had – so, when I went too deep into a turn, like at Dry Sack, I could just finger the lever to cram off a little speed and get things under control. Best of both worlds…

And that’s really the cliché which summed up the Yamaha best – it’s was the 500GP class’s top all-rounder as the best overall package in terms of power and handling, engine and chassis. As such, as the two-stroke 500GP era came to an end in favour of MotoGP after 30 years of ever-increasing engine performance coupled with reduced weight, the YZR500 was the 2000 season’s deserved World Champion machine, with Yamaha’s seven riders proving its worth race after race. Strength in numbers – aboard a very fine motorcycle. Carlos Checa told me that when his YZR500 wasn’t running the way he wanted it to, he called it his Pizza delivery bike. Beats Uber Eats, anyway…

2000 Yamaha YZR500 OWK6 Specifications

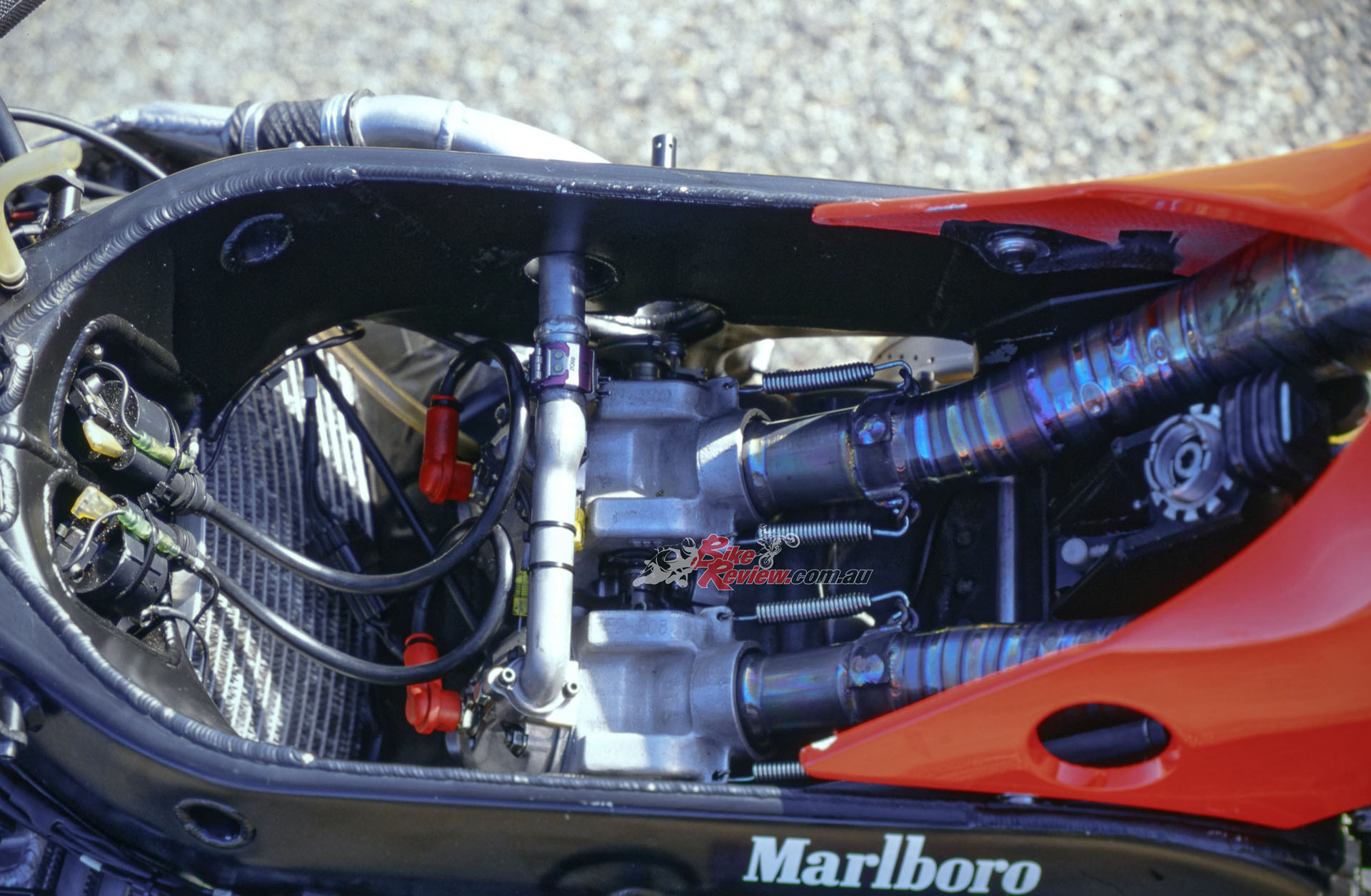

ENGINE: 498cc water-cooled 75-degree V4 crankcase reed-valve two-stroke, with twin contrarotating crankshafts, 54 x 54.6mm bore x stroke, 4 x 35mm Keihin electronic powerjet flatslides with electrically-operated guillotine-type YPVS power-valves, Yamaha electronic CDI with programmable advance curve, six-speed extractable gearbox, multiplate dry clutch.

CHASSIS: Fabricated aluminium twin-spar frame, fully-adjustable 43mm Öhlins inverted telescopic fork, fabricated aluminium swingarm with fully-adjustable Öhlins monoshock and progressive-rate link, 23.5 degrees (adjustable) rake, 1395mm wheelbase, 54/46% static weight distribution, 2 x 290mm Brembo carbon discs with four-piston radially-mounted Brembo calipers (f), 1 x 210mm Yamaha steel disc with two-piston Brembo caliper (r), 12/60-17 Michelin on 3.50in. Marchesini forged aluminium wheel, 18/67-17 Michelin on 6.25in. Marchesini forged aluminium wheels.

PERFORMANCE: Over 180bhp@12,500rpm (at gearbox),128kg with oil/water, without fuel tank, top speed 310 km/h (Mugello).

OWNER: Yamaha Motor Co., Iwata, Japan.