The title-winning Laverda was a masterpiece of development. This is the story of how it was conceived and built into a successful racer, and what it was like to ride. Pics: Kel Edge

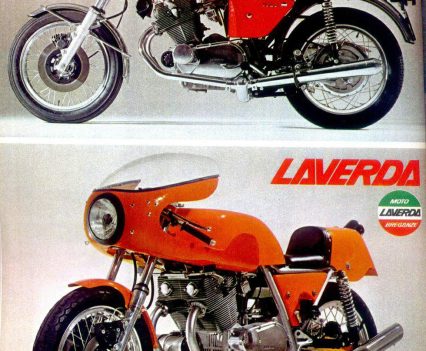

Laverda used racing as a means of developing new models, and showing the finished product to be both fast and reliable. Hence the family-owned company’s proud record of success in 1970s Endurance racing, especially with its iconic parallel-twin 750 SFC tangerine dream…

Laverda made orange a cool colour denoting performance combined with allure, long before any KTM put a tyre to tarmac, as opposed to dirt. So as the historic Italian marque celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, it’s opportune to recall the ultimate Laverda racer, the fastest and most powerful twin-cylinder trajectile ever to leave the small but successful Breganze factory in NE Italy, near Vicenza. Except, this scourge of the Japanese fours and British triples that it raced against and defeated, wasn’t ultimately created in Italy, but in – Australia.

Laverda made orange a cool colour denoting performance combined with allure, long before any KTM put a tyre to tarmac…

Sure, it’s a pity that Australia’s thrilling Post-Classic Period 5 racing class for air-cooled Vintage Superbikes doesn’t have any Italian bikes up at the sharp end of the field nowadays, rubbing handlebars with the Suzukis and Hondas as well as the Irving Vincent V-twin in recapturing the no-holds struggle for streetbike supremacy of Superbike’s early days. But it wasn’t always like that, for back in 2001 Ken Watson defeated the overbored four-cylinder J-bikes, Triumph triples, Ducati desmo V-twins and assorted two-strokes to win the Australian Post-Classic Championship title on the parallel-twin Laverda 915 SFC that was massaged into race-winning condition by the bike’s owner Chris Cutler, and ex-GP Sidecar racer Pete Campbell.

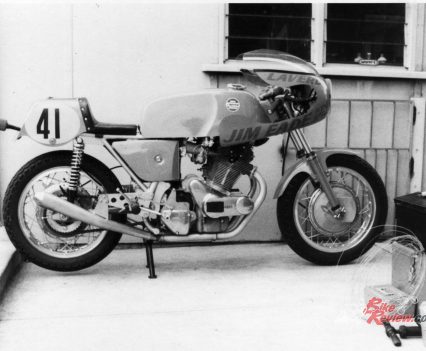

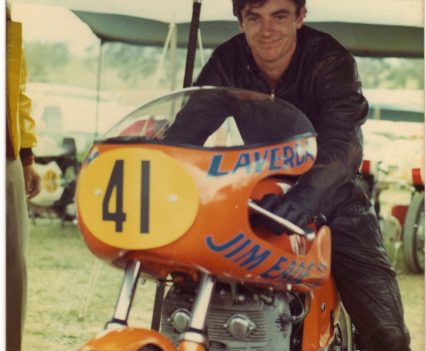

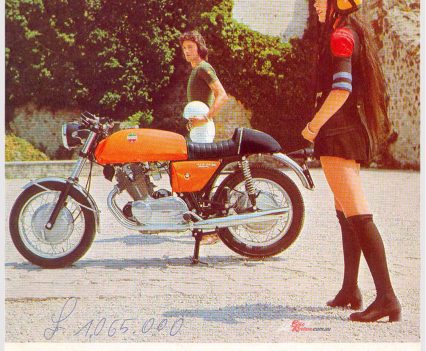

The bike that led to that success was one of the two drum-braked 750 SFC models imported into Australia of the 549 examples Laverda built from 1971-76, out of the 19,000 twin-cylinder 650/750cc bikes manufactured prior to their replacement in the mid-‘70s by the 1000cc three-cylinder models, and smaller-capacity 500cc twins. Bearing chassis no.11085, this was sold by Sydney dealer Jim Eade in November 1972 to up-and-coming NSW racer Vic Vassella.

Vic wanted something faster and more exotic than the Norton Commando he’d begun racing on. Vassella got it for trade price, on condition that he raced it and put the Jim Eade name on the fairing, but considering it cost him $2,700 at a time when the list price for a Honda CB750 was just $1,670, it still must have required quite some conviction for him to actually sign the cheque.

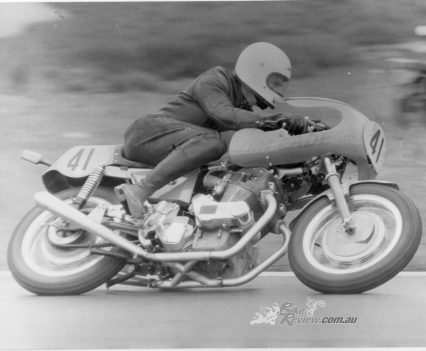

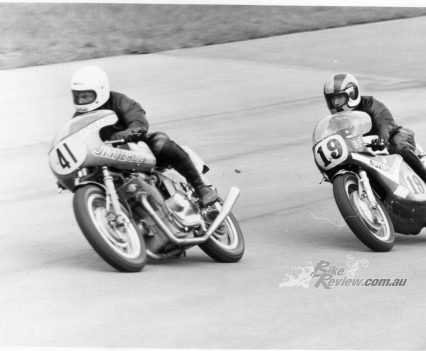

But Vic had already ridden a less potent Laverda 750SF in Australia’s first-ever Formula 750 race at the Oran Park track, so he had an idea what to expect, and when a couple of weeks after purchasing the SFC he finished second to a Suzuki TR500 GP racer in an Unlimited Open race at the same track on his first outing aboard it, this augured well.

He campaigned the Laverda for the next three season in Production, F750 and Unlimited class racing, with consistent top three finishes and the occasional win. But getting disqualified from a second place finish in a push-start Unlimited Open-class race at Amaroo Park, after using the starter button to fire up the engine while still pushing, had him lamenting he was being penalised for riding a technically advanced motorcycle – because few other bikes had electric start back then, the rules didn’t specifically forbid you doing that!

But after three seasons of racing the Laverda began struggling to remain competitive against the increasingly reliable two-stroke opposition, and the new bigger-engined Kawasaki Z900s, so Vassella retired it to his garage in 1975, then eventually sold it to Chris Cutler, an NZ-born metallurgical consultant today living in Cape Town, South Africa. “I rode it quite a bit on the road until July 1995, when I decided it wasn’t well enough to be used anymore, so I took it completely apart, and rebuilt it,” recalls Chris today.

n restoring the Laverda, Cutler decided to put it into race trim for the one-off Australian TT public roads race in Port Kembla, NSW in Easter 1996.

In restoring the Laverda, Cutler decided to put it into race trim for the one-off Australian TT public roads race in Port Kembla, NSW in Easter 1996. Vic Vassella had agreed to be reunited with the bike, but thought better of it when he saw the unforgiving nature of the street circuit, whereupon Ken Watson, a talented 80s and 1990s road racer who’d enjoyed plenty of success on such tracks in Malaysia and elsewhere, and had seen the SFC being rebuilt, volunteered to race it.

Ken Watson, a talented 80s and 1990s road racer who’d enjoyed plenty of success on such tracks in Malaysia and elsewhere, and had seen the SFC being rebuilt, volunteered to race it.

“Ken ended up second in the Post-Classic class, but with the lever coming back to the ‘bar on the original SFC drum brakes!” recalls Chris. “He had another couple of rides and said – look, we must get this thing to go faster. It was indeed pretty standard, so we put it onto methanol and stuck a four leading-shoe Ceriani brake on it, and that was better – now we were finishing on the podium, with around 65bhp at the rear wheel. However, it would now stop, but wouldn’t go around corners so fast because of the raked-out steering geometry with a 28º head angle, and this detracted from Ken’s quite aggressive cornering style. I wasn’t about to cut up a perfectly nice original bike, so we said alright, we’ll build a replica frame but with different geometry – and that’s how it all began.”

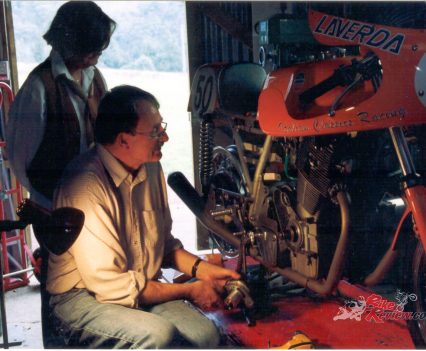

Taking a 750SF Laverda chassis, Cutler commissioned Pete Campbell to build a bike around this, firstly by replicating the additional SFC bracing on the frame, and steepening the head angle to 24º via eccentric cups, with 95mm of trail delivered via triple-clamps specially made to visually replicate the original Laverda parts, and keep the Eligibility stewards happy.

A period-style box-section swingarm later cured the problem of the original Laverda one breaking under the extra torque of the new engine, providing a much shorter 1435mm wheelbase compared to the original 750SFC’s 1470mm stride. This also laid down the extra performance from the now much more potent motor built by Wollongong engineer Chris Dowde, using the large stock of spare parts Cutler had assembled down the years.

“Steepening the head angle to 24º via eccentric cups, with 95mm of trail delivered via triple-clamps specially made to visually replicate the original Laverda parts”…

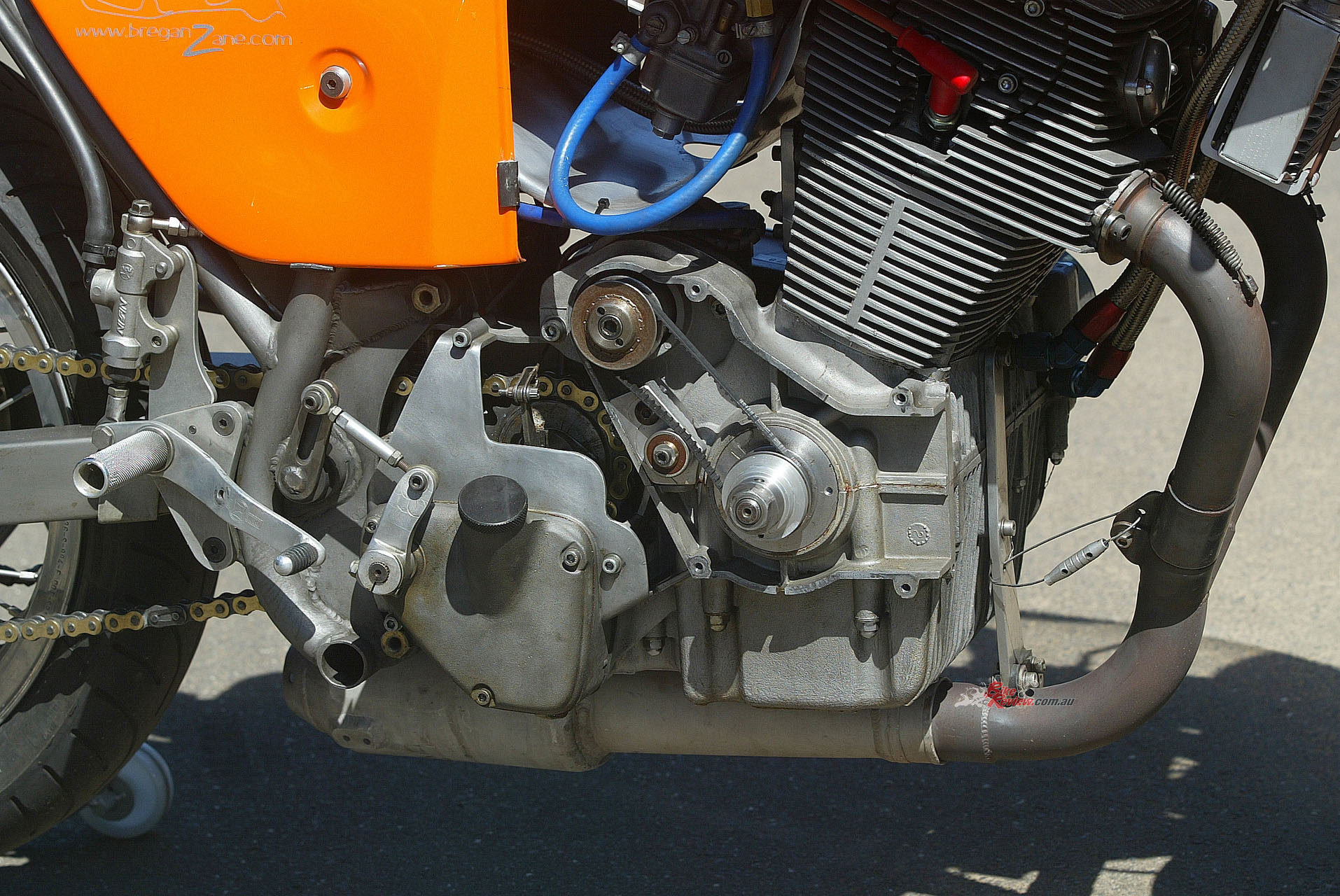

The original 744cc 80 x 74mm engine dimensions were first taken out to 874cc via a welded-up stroked roller-bearing SF750 crank built by Vee Two Ducati specialist Brook Henry, who lightened it by machining the webs to a D-shape, and fitted Ducati 900SS conrods and modified Suzuki SP370 pistons to the result. Together with an extensively modified ported and flowed cylinder-head, which was then skimmed to deliver a 12.5:1 compression ratio for an engine running on methanol, this delivered 87 bhp at 7,800rpm almost straight out of the box.

40mm PHM pumper Dell’Ortos with their accelerator jets removed were fitted, and valve sizes vastly increased to 47mm inlets and 40mm exhausts (originals were 41.5mm/35.5mm) via modified stainless steel Nissan car valves, with purpose made dual springs. “The cylinder-head was bolted directly to the SF block, which was bored out until we had no rim, with only a copper sealing ring actually where the liner is,” says Chris. “That was bolted directly to the crankcase as well – there were no gaskets anywhere in this thing!”

“12.5:1 compression ratio for an engine running on methanol, this delivered 87 bhp at 7,800rpm almost straight out of the box”…

This substantial power increase was delivered courtesy of a wild new camshaft made by Ivan Tighe Cams in Queensland, driven by a heavy duty duplex chain with aluminium sprockets and a modified Jaguar V12 chain tensioner. “The cams are nothing like an SFC, and they’re nothing like anything else,” says Cutler. “They were very cleverly dreamt up via a computer programme which gave very odd valve timing, but it made it really go quick, though it would spit a lot of fuel out! But the lift isn’t too high, because otherwise the valves kept touching the piston.”

To handle the extra power, Cutler concocted a five-speed gearbox combining SF and SFC shafts with specially made gears to close up the taller ratios, matched to the robust 13-plate stock wet clutch designed for Endurance racing. But the original oil-bath triplex chain primary drive proved troublesome, and the belt primary replacing it still ran in oil and sometimes overheated.

The 2-into-1 exhaust built by Pete Campbell according to dirt-track Speedway principles turned out to give 5bhp more than the factory 2-1 period race exhaust, and a belt-driven self-generating Kröber ignition with single coil was fitted after the two-up parallel-twin motor’s considerable low-down vibration kept destroying the batteries for the Dyna total-loss CDI Campbell originally used. An original Veglia analogue tacho was fitted which Cutler had, er, reprogrammed!

“I got KTT Services to make it for me,” he admits with a twinkle. “The bike revs safely to a little over 7,500 rpm, but the rev counter is not calibrated correctly, and shows the red line at 10,000rpm. Ducati people always used to come and look at that, and it really pissed them off – does any Laverda really rev that high??? It was just a bit of gamesmanship – but it kept people guessing!”

To ensure the new frame delivered the improved handling he was aiming for, Cutler contacted Maxton chassis guru Ron Williams in the UK to obtain a pair of aluminium-bodied Koni shocks and a new set of internals for the 38mm Marzocchi fork Campbell had sourced off a Ducati, all specially set up by Maxton to suit Ken Watson’s weight, and the geometry of the bike.

Since Ken Watson never used the rear brake anyway, they fitted a tiny 125mm SLS drum off a Honda trials bike!

Dry weight of the EVO Laverda had been slashed to 167kg including engine oil – removing the electric starter, generator and battery saved upwards of 20kg alone – and to stop this Campbell fitted a pair of 280mm cast iron Scarab front discs off an MV Agusta and a 230mm Kawasaki rear mounted on a Talon speedway hub, all with AP-Lockheed calipers. However, the Eligibility police decided that the rear disc was post-period, so since Watson never used the rear brake anyway, they fitted a tiny 125mm SLS drum off a Honda trials bike!

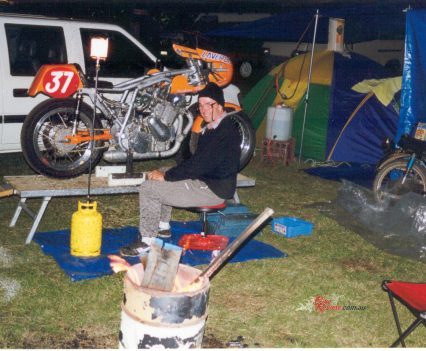

Making its debut in the Australian TT meeting at Bathurst in Easter 2000, the now much improved EVO Laverda twin allowed Ken Watson to immediately have the measure of the bored-out four-cylinder T-Rex Honda fours which had hitherto dominated Unlimited Post-Classic racing, splitting Greg Johnson and Rex Wolfenden aboard these to score a trio of second places over the weekend. “We actually ran it on petrol at Bathurst, because having finished the bike just two weeks earlier, we wanted to run it in,” says Cutler.

“Having a rear disc brake shoved us into the Forgotten Era pre-1980 class, but Ken got second overall against all the bigger-engined more modern bikes like GSX1100 Suzukis and CB1100R Hondas, and it was timed at 246km/h down Conrod Straight just ‘running it in’! The thing had heaps of torque, with a virtually straight torque curve from 4,000rpm to 7,000rpm, so it was indeed a tractor.”

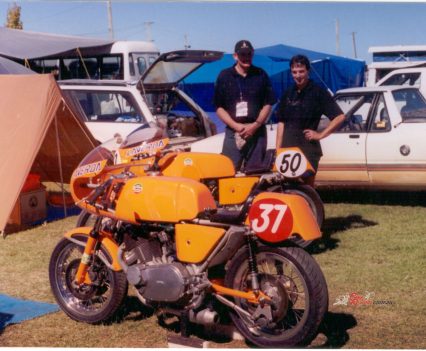

In Watson’s hands the Laverda became an established front runner in Aussie Post-Classic racing, winning many races over the next two years, before dropping a valve at the Island Classic in January 2001. That’s when the decision was made to take it out to 915cc via 87mm-bore Wiseco pistons, with the consequent 90bhp power output and extra torque – now running on methanol, with 380 main jets resulting in phenomenal fuel consumption! – resulting in the Laverda now becoming the class of the field. This came thanks to Campbell and Cutler’s dedicated development, and tigerish riding by Watson, who won the Australian Post Classic title at Winton that year, roundly defeating the bigger engined four-cylinder Hondas, Triumph triples and Ducati twins to do so. But the fruits of victory also provided the seeds of defeat.

“There was always the lingering belief with the Honda people that at Phillip Island they’d have the legs on us,” recalls Cutler. “So in January 2002 we took it there for the Island Classic, with Ken busting his guts to show them that Winton wasn’t just a fluke. In the event we were still faster than the Hondas in the first two legs, but there was a new contender in the form of a Zegers Yamaha 500cc two-stroke triple which won the first race, with Ken and the SFC second.

“There was always the lingering belief with the Honda people that at Phillip Island they’d have the legs on us”…

Peter Guest’s newly built 1,003cc Triumph Trident won the second leg after it had trouble in the first, and we came second again after the Yamaha DNF’d – but then in the third race it was our turn, and the primary chain broke. We called it a day”.

Chris Cutler’s decision to do that meant that at the end of that year, the 915 SFC Replica that he and Pete Campbell had built, plus several pickup loads of spares, were sold to Canberra-based Laverda enthusiast Steve Battison, a scientific research engineer who’d already owned half a dozen different Laverda models since catching the Breganze bug big time from his dad. Cutler continued riding the original ex-Vassella 750SFC on the road for a couple of years until his work took him to Zambia. Perhaps inevitably, Steve Battison has now acquired that original bike from Cutler [see photos].

The chance to renew my on-track acquaintance with a Laverda twin for the first time since racing the 580cc Ogier Laverda TT2 to victory at Daytona in 1984, came at the switchback Broadford circuit north of Melbourne – with the added treat of first dialling myself in aboard the impeccably restored 1972 ex-Vassella 750 SFC. But then it was time to sample what’s surely the fastest and most powerful Laverda twin ever built, on which Steve Battison had refitted the belt primary drive and a shorter fibreglass shroud over the aluminium fuel tank, which delivered a more close-coupled riding position than the typically Latin early-‘80s stretched-out stance of the stock SFC I’d just been riding.

The seat’s very low, so working the back brake would have been hard even if I’d wanted to, but Ken Watson apparently never did so either, so I guess that’s OK. But this means you feel very much a part of the bike, ensconced within it, so being able to tuck away behind the screen down Broadford’s two straights wasn’t a problem for me, despite being a fair bit taller than Ken. The Veglia tacho offset to the left (there’s a digital lap-timer in the centre) has the famous but spurious ten grand redline that wound up ducatisti so well back then, so it reads 2,000 rpm high, and the engine’s true limit is in fact 8,000 revs, with peak power of 90 bhp delivered at 7,800rpm.

“The lightened crank assembly allows the engine to zip up the rev range almost effortlessly, as that distinctive exhaust note turns into a hollow-sounding drone at higher revs”…

And what an engine! Fire it up, and the raucous rasp emanating from the steel headers ending in the aluminium silencer parked beneath the motor has the Laverda sounding completely unlike any other motorcycle, not even a tuned Norton or Triumph with a similar two-up 360º crank. Tap the left-foot gear lever for bottom gear on the crisp-action street-pattern shifter (Ken Watson started out racing Production bikes!) which has a short, precise travel, and you can trickle away almost from a standstill with barely a touch of the clutch lever.

So it’s forgiving as well as fast, though there’s a sense of only moderate torque to make it tractable rather than peaky, instead of the trunk-twisting variety of a British twin. The lightened crank assembly allows the engine to zip up the rev range almost effortlessly, as that distinctive exhaust note turns into a hollow-sounding drone at higher revs. But this isn’t a four-stroke twin masquerading as a two-stroke, so the revs build quickly and cleanly, rather than via an abrupt lightswitch throttle response.

The moderate if ultra-flat torque curve means you need to work the gear lever fairly hard to row the Laverda along, especially from low down – there’s a surprisingly large gap between second and third gear which makes the bike hesitate a little in building speed, so it’s not as seamless as would be ideal. But unlike any other parallel-twin I ever rode before – and especially compared to the ex-Vassella stock SFC I’d tried earlier, which shook harder the more you revved it – there’s no undue vibration at any revs, and you’d never take this to be a potential boneshaker of a 360º twin, which it is. Only a few high-frequency tingles through the footrests at peak revs in fourth gear (as you must gear it for at Broadford, which has too short a pair of straights for fifth/top on the Bathurst gearing fitted) give any hint of what you’re riding. Amazing.

But the clean carburation delivered by the well dialled-in 40mm Dell’Ortos gives an eager pull from 3,000rpm upwards, with a notably stronger build of power from five grand onwards accessed via the light-action throttle. This has extra purchase for your right hand delivered via the rubber bands wrapped around the twistgrip rubber, making it semi-elliptical. Use the revs to keep the engine running hard, and you’ll be rewarded with outstanding acceleration out of slower turns by the standards of what started out life as an early-‘70s parallel-twin.

This feels a much more modern motorcycle than it says on the label. It just leaps out of turns if you keep it revving above 5,000rpm (seven grand on the tacho), hard enough when I rode it to give the four year-old 130/70 rear Avon AM23 some strife. The Laverda just rocketed out of Broadford’s uphill first turn in second gear, driving hard forward with the ‘bars waving lazily in my hands each lap as it pulled the makings of a mini-powerwheelie while still cranked over to the right, with the rear Avon scrabbling for grip, yet all seemingly controllably without any trace of a highside. Impressive!

“You’ll be rewarded with outstanding acceleration out of slower turns by the standards of what started out life as an early-‘70s parallel-twin”…

Indeed, the Laverda’s steering felt pretty sharp by mid-‘70s standards, proving Cutler’s revised steering geometry had ticked all the boxes in terms of agility coupled with stability when stopping. It gave sharp, easy turn-in under heavy braking at the end of Broadford’s top straight, where you must trail the brakes into the downhill-exit second-gear right-hander, with all the attendant risk of tucking the front wheel as you do so on a bike that hadn’t been set up right.

Yet the Laverda will let you do that, with a greater sense of control thanks to the extra leverage from the wide-spread clip-ons, which also help you flick the bike easily from side to side through Broadford’s downhill Esses, and powering up around the blind off-camber left leading on to the front straight showed that, even when cranked hard over, the Laverda would stay glued to the line I’d chosen for it, without washing out the front end as the revs built.

Even if it did so because I’d picked the wrong line, it was easy to pull the SFC back to correct that without backing off the gas – the steering is really responsive. Nice – even if a mid-session inspection showed I was working both tyres really hard, especially the front 110/80-18 AM22 Avon which was balling up the rubber right on the edge of the tyre. The Laverda felt small and nimble, especially in comparison to the much rangier if equally slim desmo V-twin Ducatis it races against, or the bulkier and heavier Honda fours and Triumph triples. However, I was surprised it didn’t brake as well as my 1974 750SS Ducati, which although 10kg heavier than the 167kg Laverda stops better, with more bite from the identical Lockheed calipers gripping 280mm Brembo cast iron discs, as against the SFC’s same-size Scarabs. Maybe the pad choice?

One feature indeed betrayed the Laverda’s age – the way it leapt around a good bit over Broadford’s several bumps, the twin Konis massaged by Maxton unable to supply enough damping to keep the wheel on the ground all the time, despite my extra weight compared to Ken Watson being available to keep it in contact with planet Earth. But on the smoother sections it put the power down quite well, to the unmistakeable sound of that unique exhaust note. The way it turns into a sort of hollow howl at high revs is almost other-worldly – this is the motorcycle equivalent of a wolf barking at the moon, then going hunting for Hondas to devour…..

Which after a decade’s absence from the starting grid, the Laverda 915 SFC did indeed venture forth to do again. At Eastern Creek’s 2011 Festival of Speed owner Steve Battison gave the keys of the bike to new rider Drmsby Middleton for him to race it for him for the first time since he’d bought the bike from creator Chris Cutler way back in 2002. Battison takes up the story: “We ran a Club meeting to prepare, and then in a field of Forgotten Era 1300s and New Era 750s like early GSX-R750s etc., we landed an outright pole position and two out of three overall race wins on debut, only faltering when Drmsby stalled the bike on the dummy grid for Race 3, and missed the start – he still recovered to win the class. Then we went to the Barry Sheene Historic Meeting to face altogether stronger opposition like Rex Wolfenden’s T-Rex Hondas and Robert Young’s Ducati, but still won the Post-Classic Unlimited class there.”

So on its return to waving the Italian flag in Down Under Post-Classic racing, the Laverda 915SLC wound up where Laverda’s many fans Down Under believe it deserves to be, on the top step of the podium. Aussie ingenuity applied to Italian Classic hardware has turned a motorcycle long considered as fit only for long distance Endurance racing into a hyper-handy short circuit tool. Some tractor!

Laverda 915 SFC Specifications (constructed in 2000)

Engine: Air-cooled SOHC parallel-twin four-stroke with 360-degree crankshaft, central chain camshaft drive, and two valves per cylinder, bore x stroke 87 x 77mm, 915cc, 12.5:1 compression, 2 x 40mm Dell’Orto PHM carburettors, Kröber self-generating electronic CDI, five-speed gearbox, Multiplate 13-plate oil-bath with belt primary drive.

Chassis: Tubular steel open-cradle frame with engine as fully-stressed member,

Front: 38mm Marzocchi telescopic forks with Maxton internals (F), Tubular steel Campbell swingarm with 2 x aluminium-bodied Koni shocks modified by Maxton (R), rake 24 degrees, trail 95mm, wheelbase 1435mm, Brakes: Front: 2 x 280mm Scarab cast iron discs with two-piston AP-Lockheed calipers Rear: 1 x 230mm Kawasaki steel disc with two-piston AP-Lockheed caliper Wheels/tyres: Front: 110/80-18 Avon AM22 on 2.50 in. Akront rim wired to Scarab hub Rear: 130/70-18 Avon AM23 on 3.00 in. Akront rim wired to Talon hub.

Performance: 167kg with oil, no fuel, 90 bhp at 7,800rpm (at rear wheel), 153 mph/246 km/h (Bathurst 2000)

Owner: Stephen Battison, Canberra, ACT, Australia