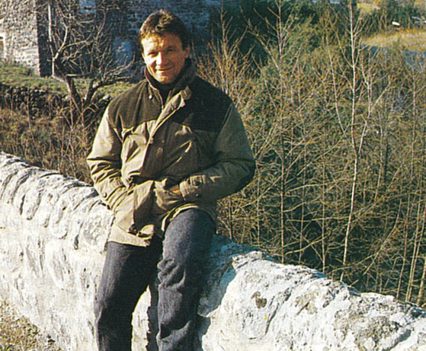

Alan Cathcart got the chance to passenger in the the LCR-Krauser in 1990. He is still recovering, mentally and physically, 30-years on! Words: Alan Cathcart Pics: Phil Masters

I really ought to have known better than to get myself talked into doing it again. I mean – how many times in your life do you have to be seriously frightened, I mean PETRIFIED, before common sense starts to take over? All I had to do was say no – but didn’t? Of course not.

The LCR-Krauser was a one of a kind machine, built by a mad man with the plan of just going as fast as possible.

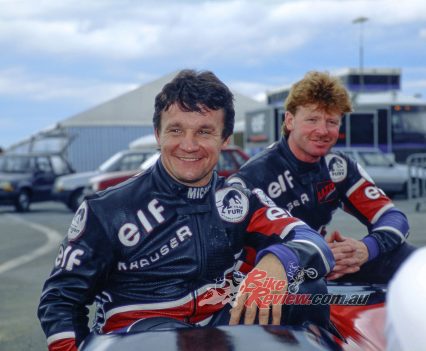

1990 World Sidecar champion Alain Michel can be such a persuasive guy when he wants to be: how could I possibly refuse another ride with him in the ‘chair’ of his title-winning LCR- chassised ELF-Krauser, even if I was the most terrified I’ve ever been.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

Sidecar racing may always have been perceived as the poor relation of GP solo racing, but in the late 1980s its popularity had never been greater among race fans in countries like Britain, Holland, Germany and Switzerland, whence the great majority of competitors hailed from.

Alain was no stranger to side-car racing. He boasted an impressive CV that spanned decades of great results.The Sidecar GPs repeatedly featured a thrilling battle for victory not only amongst the four leading contenders who’d dominated the class for the past half-decade and more – Alain MicheI, Steve Webster, Egbert Streuer and Rolf Biland, with other names appearing on the rostrum, like fraternal Swiss stars the Guedel twins and the Zurbrugg brothers, UK-based Japanese driver Yoshi Kumagaya, and British nearly man Steve Abbott.

European GPs were no longer permitted to drop the Sidecar class from the programme, which meant that spectators could see and appreciate the thrilling spectacle that the GP Sidecar mob presented. That was despite IRTA’s stated desire to get rid of the Sidecar class, which proved to be an uphill struggle as sponsors liked them for the large display space they offered on their flanks, which allowed their name to show up well on TV and at trackside.

Sidecar racing really began to kick off in the late ’80s and early ’90s with European GP’s not being allowed to drop them.

One such sponsor who had special reason to be pleased with its 1990 Sidecar racing season was ELF. It was ironic that whereas the French petroleum giant’s decade-long efforts to push back the frontiers of two-wheeled design convention with its avantgarde 500GP racers never resulted in anything much in terms of concrete track success, 1990 saw ELF achieve its first ever World title in motorcycle GP racing as a primary sponsor, thanks to France’s first-ever three-wheeled World champion, Alain Michel and his British passenger, Simon Birchall.

The LCR-Krauser uses a similar engine as the Swissauto 500, read about it here…

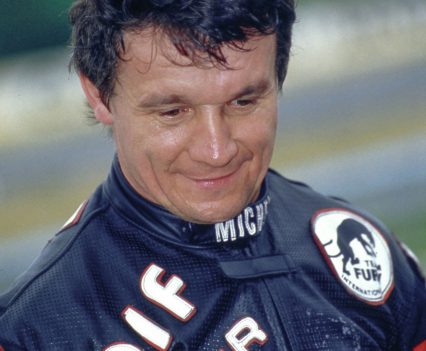

In the 15 years since finishing second in his home GP in his first season of three-wheeled GP racing in 1976, Alain Michel had raced in over 120 GPs, won 17 of them, finished second 26 times and been third on 16 occasions – 59 times on the rostrum, averaging once every two races. He’d finished second in the World championship four times – 1978, 1980, 1981 and 1985 – third three times and fourth four times, all without ever actually winning the coveted title itself until 1990, when justice was finally. At the age of 39, Alain Michel’s turn to be crowned World champion was long overdue – and thanks to his then-new partnership with Simon Birchall, 1990 was the French driver’s year. About time, too!

Alain raced in over 120 sidecar GP’s but didn’t win a world championship until 1990 on the LCR-Krauser.

Simon Birchall became Britain’s only 1990 season World motorcycle champion after being recommended to Alain by the Frenchman’s great friend but equally great rival, three-time World champion Steve Webster. He must have wondered afterwards why he bothered, seeing as Michel attributed a large part of the credit for his victory to his new passenger, who only rode with him for the first time just before that April’s US GP at Laguna Seca, which they won convincingly.

“Simon is the first passenger I have ever raced with who I can completely forget about when we’re on the track. He is so amazingly strong and fit, as well as skilled”…

“Simon is the first passenger I’ve raced with who I can completely forget about when we’re on track. He’s so amazingly strong and fit, as well as skilled, that I know I can depend on him not only to do the right thing in the chair, but to keep on doing it up to the end even of a gruelling race on a physically tiring track like Jerez or Hungaroring. This allows me to drive as hard as I can just thinking about my own race, rather like riding a solo, without having to make allowances for the passenger. Simon’s also very helpful technically, which since we do all our own mechanical preparation and don’t employ a mechanic, is very important. And personally we get on well, even if we have the occasional argument when we each know the other’s wrong about something” said Alain.

“Alain Michel’s title-winning sidecar team consisted of just three people: himself, Simon Birchall, and wife Dominique.”

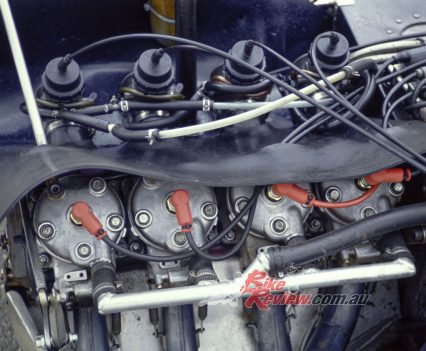

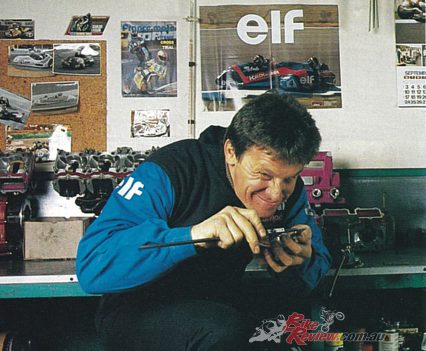

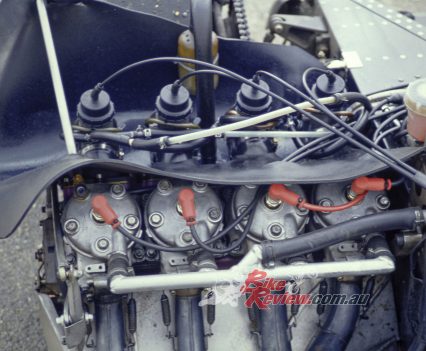

The importance of a healthy personal relationship was highlighted by the fact that Alain Michel’s World title-winning Sidecar team consisted of just three people: himself, Birchall, and Alain’s loyal wife Dominique, who acted as everything from team manager to chef to accountant – a far cry from the title-winning 500GP solo teams! For Alain Michel’s title wasn’t only a tribute to his skill as a driver, but as a race and development engineer, too, since he not only built his own engines for each race, but also carried out an extensive ongoing development programme on the liquid-cooled Krauser transverse in-line four-cylinder crankcase reed-valve two-stroke motors used to power his Swiss-built LCR chassis.

Alain Michel’s Krauser engine yielded no less than 175 bhp at 12,500rpm at the gearbox sprocket by the time he finally clinched the title with five wins out of the 13 races run. around 190 bhp at the crank – by the time he finally clinched the title in 1990, with five wins out of the 13 races run. That’s around 12% more than the best equivalent 500GP solo, the NSR500 Honda then delivering around 170 bhp at the crank – some going for a transverse in-line engine loosely based on Yamaha’s TZ500 piston-port solo engine of circa 1980 vintage, although by then there wasn’t a lot of Yamaha parts employed anymore, either on grounds of cost, or availability, or plain reliability.

After all, the old TZ500 solo gave around 115 bhp on a good day, which by 1983 when I was last previously foolish enough to ride in a chair, the Sidecar men had jacked up to around 130 bhp by narrowing the powerband and going for revs.

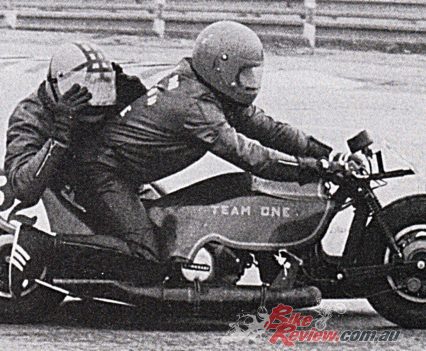

Alan hangs on for dear life. Alain is only warming up the tyres… If only there were heart rate monitors back then!

But from there to 175 bhp was a big hop, and was only made possible by German enthusiast Mike Krauser’s brave decision as a long-lived supporter of three-wheeled racing to subsidise the development of a set of liquid-cooled reed-valve crankcases into which Yamaha components could be fitted, so as to give more power, more reliably, as well as to improve power delivery.

By the mid-1980s when the Krauser engine first appeared, Sidecar GP powerbands had become ultra-narrow as power outputs of the piston-port motors escalated, but by 1990 Alain Michel’s engines drove from 8,500 rpm upwards and peaked at 13,000 rpm to offer an adequate degree of overrev, though you wouldn’t describe the power delivery as anything other than violent, thanks to the extreme porting of the nine-port (6 transfer/3 exhaust) TZ250 cylinders employed on the Krauser cases, fed by 39mm elliptical-choke flat-slide Dell’Orto carbs.

Massively bloated expansion chamber pipes matched to mechanically-controlled variable-geometry exhaust valves ran forward from the rear-mounted engine’s forward-facing exhaust ports beneath the driver’s body, and the extra space available to optimise pipe design compared to a solo, plus the lack of necessity to soften the power delivery so as to make a two-wheeler rideable even by Kevin or Eddie, was mainly responsible for the extra power on tap from the three-wheeler’s motor versus a works V4 solo. And what gave the Michel motors the edge compared to their rivals was a combination of Alain’s tuning skills, plus a little help from his friends at ELF, who provided him with a special 124 octane brew only supplied to their contracted riders, compared to the 118 octane stuff they sold to everyone else.

This sort of output far beyond the original TZ500 figures obviously placed a huge strain on the transmission, and although the original-design Yamaha dry clutch was maintained the gearbox had to be considerably uprated. After persistent breakages which probably cost him the World title at least once in the previous decade, and threatened to do so again in 1990, Alain now used an expensive but strong gearbox made by ARCO in Italy at RoIf Biland’s behest.

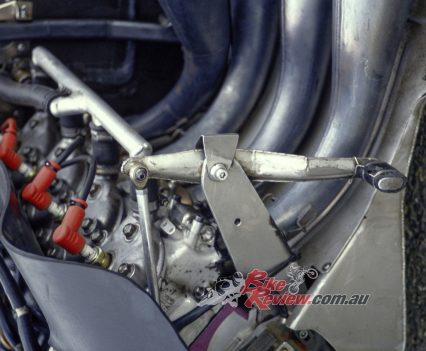

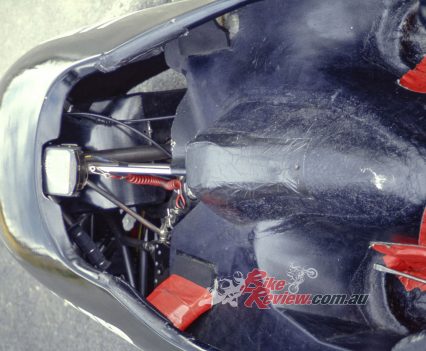

Squeezing myself into the narrow cockpit in pit lane – they were much too sensible to actually let me drive it, always assuming I could have done, given that the cockpit was moulded around Alain’s physique, and he was six inches/15cm shorter than me! – showed that he changed gear with his right foot, one forward and five back, with the brake lever on the left operating all three brakes via an integrated system, with a cockpit-mounted balance knob which allowed him to alter the balance between front and rear wheels during a race. Alain experimented with carbon discs in 1989 before adopting them on the two main wheels, with a non-ventilated steel disc on the sidecar which had a smaller caliper than the four-piston items derived from AP Lockheed’s F3 car catalogue fitted to the other two Ronal wheels.

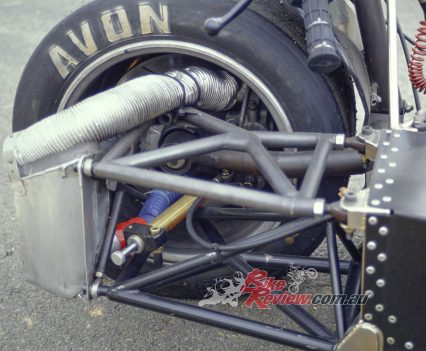

The LCR chassis was built by Louis Christen in Switzerland, the man who invented the modern ‘worm’-type Sidecar design back in 1981, and whose machines then dominated GP Sidecar grids even though he only built an average of 15 such machines each year at a retail cost back then of around US$ 30,000, without engine and wheels. After Rolf Steinhausen retired from GP racing in 1989, there were no further Continental-style right-hand Sidecars on the scene, only British-style left-hand chairs presumably favoured because most circuits were by then run in a clockwise direction, hence a predominance of right-handers where the rear engine location helped the passenger to keep the rear, driving wheel on the ground, even though it wanted to lift skywards.

“Given that carbon thrives on heat, its application to sidecar braking systems is a natural, but you can have too much of a good thing and hefty ducting is fitted to cool the brakes to somewhere around their four-figure operating temperature.”

The LCR chassis was made from aircraft-spec aluminium sheet cut to size, and rivetted and bonded with Araldite to form an extremely stiff structure consisting of a central backbone containing the UK-made bag-type fuel cell. Over 800 rivets were used to build the structure, to which was attached the carbon-fibre passenger platform.

Because the rules stated that the front, steering wheel had to be directly linked to the handlebars, the chassis employed a parallelogram hub-centre front end design rather than the car-type steering box you might have expected what appeared to be merely a racing car with a wheel missing to carry, but car-type suspension uprights were employed on the other two wheels, with Koni dampers on the two main ones, but no suspension on the sidecar wheel, only a rubber bump stop.

“Three years ago we moved the sidecar wheel forward to speed up the steering, even though it sacrificed front end grip”

13-inch Ronal wheels which Alain was one of the first to adopt when he started racing Sidecars after a successful career on solos, winning the 1972 French 500cc Production title on a Honda CB450, were fitted, shod with Avon rubber – a low-profile 8/20 at the front and higher-profile 21s on the other two wheels, commonly fitted to a 9-inch or 10-inch wide rim. Where solo riders experiment with trail, offsets, head angle and ride height, Sidecar drivers play around with camber angle and especially the location of the sidecar wheel relative to the other two, in order to alter handling characteristics.

“Three years ago we moved the sidecar wheel forward to speed up the steering, even though it sacrificed front end grip” said Alain. “But then grip became more important, so we changed back again, and I also altered my riding style, so now I go slower into turns, but get the power on early for a good drive out – the other set-up gave too much tyre scrub, which wore out the tyres very quickly. But each driver has his own special style and requirements, so although LCR build the same basic chassis for each of us, they alter it to suit each driver’s needs.”

Being a passenger on one of these is no walk in the park, with plenty of space to be flung around in.

Covered with all-enveloping Kevlar bodywork, the ELF LCR scaled 202kg with oil and water, no fuel, and carbon discs (a little more with steel brakes fitted), and with a wheelbase of no less than 2285mm well deserved the ‘worm’ epithet, especially when you saw it wriggling round turns in the hands of its World champion master!

The Ride – Truly Terrifying!

“C’mon guys, you’ve had your laugh, help me out, please? We might need a bit of soapy water to get my hips through”.

Only, I was about to be wriggled, and with the moment of truth approaching, I was fast running out of excuses. Fate had conspired to land me in this invidious position, with the ELF PR road show rolling up to the French Pau-Arnos circuit in the foothills of the Pyrenees just as the Andorra GP race meeting I’d been competing in was winding to a close. ”Aha!” said Alain Michel when he spotted me in the paddock all unaware of my impending doom. “No escape now! ELF Expects!” And indeed they did: never mind that he’d been trying to get me back into his bloody Sidecar for the previous six years – here was the payoff for all those years of scoop tests of successive ELF 500GP solos, only on a different breed of hub-centre device.

“They say racing drivers make the worst car passengers because they can’t bear not to be in control of the wheel. For sure, the sense of helplessness, of total inability to control your own destiny once you’re parked on that minuscule sidecar platform and accelerating down pit lane is the biggest mental hurdle a racing sidecar passenger has to overcome”…

I still had Simon Birchall’s urgent words of wisdom echoing round my head from when he’d showed me the various hand-holds just before setting out. “Whatever you do, don’t let go of the left-hand strut, else you’ll be out the back as soon as you hit a bump or there’s a snatch in the transmission,” he warned. Is that why they call these ‘rear-exit sidecars’, compared to the old front-engined, front-exit ones?? The strut in question was a metal bar sticking vertically up from the sidecar floor, and you better believe that for the first of my two three-lap sessions of the switchback Pau-Arnos track, I clutched my life-saving hand-grip like a drowning man clinging to a lifebelt.

“My helmet was bobbling about so much he must have thought I was nodding, because next thing I knew, he was screaming the motor to its thirteen grand redline.”

Because there’s little doubt that Sidecar passengering, especially at GP level, is not only one of the most courageous ways that man has yet dreamed up to earn a living, it’s also one of the most physically gruelling. I got my first taste of that 600 metres from pit lane, as Alain slammed on the brakes at the end of the top straight, and I was catapulted forward and only prevented from making a frontwards exit by the sidecar streamlining slamming into my ribcage. Since he’d already done a few laps with Simon aboard to check everything out, the carbon brakes were nicely warmed up, and their effect when Alain stepped on the left foot pedal was both immediate and total.

If the old ventilated steel discs in use when I last rode with him back in ’83 were so effective it was like running into a brick wall, now with the carbon brakes it’s like the wall ran into you! Having raced on the same circuit the day before, I knew where the braking points for a solo should be – but these have absolutely no relevance in Sidecar terms, because not only can a three-wheeler brake far later safely – well, everything’s relative – it can also scrub off loads of speed by being chucked sideways in the turn in a lurid three-wheel drift, with the passenger hanging on for grim death.

Cathcart leaning over the other side to hold on is nothing compared to how far the professional passengers lean over.

Coming on to the main straight Alain half-turned back towards me from his position about the length of a soccer pitch away in front of me and stuck up a questioning thumb. I didn’t dare let go of anything to reply, and the effort of keeping my head more or less where I wanted it to be – like, attached to my neck! – in the unbelievable turbulence of the unprotected slipstream prevented me answering him that way. My helmet was bobbling about so much he must have thought I was nodding, ‘cos next thing I knew he was screaming the motor to its thirteen grand redline, and my arms were being yanked out of their sockets as I desperately clung on.

The acceleration was mind-boggling, despite the fact that the 500cc engine had two people to pull round the track, rather than just one; or maybe it’s because I was so close to the ground and not in control of my own destiny, but the performance seemed even more mind-blowing than riding a Yamaha or Honda factory team’s 500GP V4. However, that paled into nothing alongside the effect of the G-forces in cornering, and the slam-dam power of those ultra-effective brakes. After two laps my neck was already aching from the huge effort required to counter the centrifugal force and drape myself over the driving wheel in right-handers.

“My forearms were already starting to swell up from the effort of holding myself in the chair: it’s so unbelievably physical, you wonder why more passengers don’t suffer from the solo riders’ complaint of tendonitis”…

Left-handers I refused to concern myself with, because nothing was going to make me let go of that central hand-hold, and if you wanted to lean out over the sidecar wheel, you had to swap hands expertly and smoothly with a practised skill that I had no intention of acquiring!

“Looking at Simon Birchall’s massive forearms, about as thick as the average man’s leg, you could see why.”

“It’s something you have to build up to and get yourself fit enough to do,” said Simon matter-of-factly, “but once you’ve got the experience and the fitness, it’s OK. The worst times are at tracks like Jerez or Laguna Seca where there’s no straights to speak of, and so you’ve no time to rest. Hungaroring’s like that too, all corners, with kerbs that are quite high, so I was rubbing the tips of my fingers on the concrete in left handers, as well as wearing out a pair of boots, which is quite normal – I reckon to go through five or six pairs of Daytona passenger boots in a season. But you put up with all that because the satisfaction of making a good team and working in partnership is tremendous – especially if you win a World title at the end of it all!”

Drifting the outfit, power-sliding the rear end, standing it on its nose into turns, running the sidecar wheel on the grass to cut inside a rival on a left-hander like the final turn at Laguna Seca, rubbing fairings round fast sweepers at 200 km/h-plus, stuffing it up the inside of a rival on the brakes and letting the tyres scrub off the last few k’s before you ram him – all this and more is part of life’s rich passion in the esoteric but spectacular world of Sidecar racing.

This bike was truely an amazing feat of engineering, giving us a strengthened respect for the pilots and builders.

No wonder its popularity was increasing around the world back then, for Alain Michel and his rivals regularly regaled Grand Prix race fans with a unique spectacle on a fraction of the budget of even an average 250GP team. That’s why you wouldn’t ever find me in the bar or the Press room when the Sidecars took to the track at a GP. Only, you wouldn’t find me in the sidecar platform, either: thirty years on, my mind and body are still recovering from six laps round Pau-Arnos with the World champion.

1990 LCR-Krauser Sidecar Specifications

ENGINE: Liquid-cooled transverse in-line four-cylinder crankcase reed-valve two-stroke 498cc with six transfer, three exhaust ports, and mechanically-controlled variable-geometry exhaust valve, 4 x 39 mm Del’Orto elliptical-choke flat-slide with fuel pump, 6-speed ARCO with Multiplate Yamaha dry (7 friction/7 steel).

CHASSIS: Sheet aluminium LCR monocoque, riveted and Araldited, Parallelogram with hub-centre steering, Fabricated wishbone uprights Koni oil-damped shocks used on front and rear wheels – sidecar wheel has rubber block only, 2 x Carbon Industrie carbon discs with AP-Lockheed four-piston calipers on front and rear wheels, and 1 x 254mm ventilated AP-Lockheed stainless steel disc and two-piston caliper on sidecar wheel, and coupled hydraulic actuation of all three by foot pedal, with auxiliary handlebar system to front wheel only, 8/20 x 13 Avon on 8.00 in. 10/21 x 13 Avon on 10.00 in. 9/21 x 13 Avon on 9.00 in. all on cast-aluminium Ronal wheels.

PERFORMANCE: Over 280km/h, 175bhp@12,500 rpm (at gearbox), 202 kg with oil/water, no fuel, with carbon brake discs.

OWNER: AM Energie, Montélimar France.

1990 LCR-Krauser Sidecar Gallery