Superbly conceived and exquisitely manufactured, Irving Vincent racers are two-wheeled works of art. Alan has ridden them all and takes us on a 16-year journey. Pics: Kel Edge, Russ Murray

Decades on from his tragic death back in 1995, Kiwi visionary John Britten’s spirit of two-wheeled engineering self-sufficiency lives on. But it’s on the other side of the Tasman Sea that Britten’s against-all-odds home-brewed engineering ethos continues to flourish…

Mind you, Aussie brothers Ken Horner, 69, and Barry, a year younger, cover both sides of the equation, in defeating both ancient and modern competition in Australia, the UK and USA with the series of exquisitely engineered Irving Vincent racers they’ve conceived and developed over the past twenty years in their high-tech manufacturing company’s 3,000m² factory in Hallam, a Southeastern suburb of Melbourne. In doing so, they’ve earned deserved acclaim for the revival of the Vincent name with race-winning bikes they’ve made entirely themselves. Just like John.

For anyone unaware of the Horners’ achievements so far, the past two decades have seen the succession of 1300cc OHV Irving Vincent V-twins they’ve created confront and defeat the über-tuned four-cylinder 16-valve DOHC Japanese Superbikes of equivalent capacity they share the track with in Aussie Post-Historic racing’s premier Period 5 class, covering the 1973 to 1983 era.

Four-times World Champion and 19-times NZ Champion Hugh Anderson and Alan dicing at Broadford in 2015, what a shot – two amazing motorcycles built with Aussie and Kiwi know-how…

But additionally, in 1600cc guise this air-cooled four-valve pushrod racer defeated the latest and greatest liquid-cooled eight-valve V-twin Superbikes from Italy to win the 2008 Daytona ProTwins race, ridden by Craig McMartin. He then teamed up with Beau Beaton to best the cream of British Classic racers in the 2014 Goodwood Revival on a genuine 1948 Vincent Series B Rapide formerly owned by the President of the Australian Vincent Owners Club, which the Horners purchased and developed into a race-winning bike.

Check out Alan’s previous Throwback Thursday articles here…

The Horner brothers’ other self-built creations are conceptually based on the historic Vincent 50º V-twin motorcycle and are built as a tribute to its creator, legendary Australian engineer Phil Irving, who went on to design Australia’s Formula One Repco V8 race engine which took Jack Brabham and Denny Hulme to successive F1 World Championships in 1966-67. The Horners struck up a friendship with Irving after he moved back to Australia, where Ken and Barry both tasted success in Sidecar racing with self-built outfits, in Ken’s case using a 1300cc Vincent motor he tuned himself.

Watch Cameron Donald and Kaz Anderson take on Bathurst on the Irving Vincent outfit

He retired from racing in 1977 to start his own engineering company, later joined by Barry, and today K.H. Equipment Pty. annually exports over half its production of air starters for the mining and fuel exploration (i.e. oil and natural gas) industries – any hazardous environment where sparkless function is a prerequisite – to China and the USA. Its 30-strong workforce turns out high-precision machined components on an array of hi-tech CNC equipment. But its CAD/CAM capability has also seen KHE manufacture trick race components for Australia’s leading V8 Supercar teams, and it was thanks to this that the brothers came into contact with Phil Irving in the 1970s, remaining friends with him until he passed away in 1992.

After a six-year sabbatical from motorcycles in the 1990s, while they built a prize-winning 46-foot (14-metre) ocean-going yacht which they never found time to sail, the Horners went back to their bike building roots in 1999, to design and build a new Vincent motor for Classic racing as a tribute to Irving – three in all originally, a number that’s since grown to over 20. The prototype Irving Vincent duly appeared at the 2003 Island Classic, the first of a series of two- and three-wheelers entirely manufactured by KHE.

The prototype Irving Vincent duly appeared at the 2003 Island Classic, the first of a series of two- and three-wheelers entirely manufactured by KHE…

“The engines are based on the original Vincent design, but stretched in capacity and re-engineered to correct all the original shortcomings in that,” says Ken Horner. “We decided to make complete bikes ourselves, but we didn’t want to call them Vincents, although that’s what they are, because of having to pay royalties if we did to the Holder family in the UK, who own the Vincent name. So instead we decided to call them Irving Vincents, to underline Phil’s contribution to the marque, for which many feel he never got due recognition, and we got approval to do so from his widow Edith, before registering the name.”

That first Irving Vincent racer was in fact a Sidecar which first appeared in Barry Horner’s hands in January 2004, and with Chris DiNuzzo as passenger he duly won the New Zealand Historic title on it in February 2006. Then came the first Irving Vincent solo racer, the first of a series of eighteen such bikes entirely manufactured by KHE, a carburetted 1300cc machine which the Horners debuted in the Post-Classic Period 4 (1963-72 inclusive) class at the Island Classic at Phillip Island in January 2007, in the hands of Australian ProTwins champion Craig McMartin.

They were rewarded with a quartet of race victories on the Irving Vincent’s debut appearance – but it was its encouraging performance that same weekend in the Forgotten Era International Challenge against all the later Period 5 bikes from Australia, the UK and NZ that was most significant, with eighth place in the first race, followed by a trio of fourths against the 40-bike field. “There wasn’t much competition for us in the older bike class, and it’s not much fun winning races by more than the length of the front straight,” said Ken Horner. “But going up against the more modern four-cylinder Superbikes with our pushrod twin seemed more of a challenge. So that’s what we decided to do.”

To good effect, since the P5 Irving Vincent thereafter became a serial race winner in McMartin’s hands against the fleet of tuned-up Japanese four-cylinder Superbikes maxed out in capacity, with braced-up frames fitted with modern suspension to cure their inherent handling ills. In doing so, it became a firm fan favourite as the quixotic underdog struggling to defeat seemingly more modern, more sophisticated and more potent opposition, as it often did. It became commonplace to watch the lazy-sounding, low-revving, air-cooled 1300cc pushrod V-twin leaving riders of the calibre of Wayne Gardner, Robbie Phillis and Mal Campbell trailing in its wake on their Japanese fours, just as in 1600cc form it did the modern Ducati Superbikes ridden by such illustrious names as Doug Polen and Larry Pegram, in the 2008 Daytona ProTwins race.

In its first four years of competition after that January 2007 debut outing at Phillip Island, Irving Vincent riders Craig McMartin and his subsequent stand-in through injury, Beau Beaton, won an amazing 29 P5 Post-Classic races out of 32 starts there and at Eastern Creek, with just three DNFs – so basically, when the bike finished, it won. One of those DNFs came from a dropped valve, which meant McMartin beat former 500GP World champion Wayne Gardner’s hotrod Honda four ‘only’ three out of four times that day. But another DNF came from a crash which sidelined Craig for over a year, and necessitated Beau Beaton replacing him, which he did to such good effect that the Horners then built him a second bike identical to McMartin’s. Double trouble for the four-cylinder monsterbike mafia….

In fact, before that I’d become the first person ever to ride the 1300 Irving Vincent racer when the Horners asked me to give it a shakedown test in 2006 on the bumpy, switchback Broadford track 60km/40mi north of Melbourne. With the bike literally finished the night before my ride, I was prepared to have to spend the first part of our sunny summer session dialling in the freshly-minted born-again Vincent. Not a bit of it. After watching the brothers fire it up using a remote starter identical to the one the Suzuki MotoGP team used on the factory GSV-R, I took to the track and discovered the sound of rolling thunder issuing from the 2-1 exhaust with two-and-a-half inch diameter [63.5mm] straight pipes, was the harbinger of a bike that was ready to roll straight from the womb.

At that early stage of its evolution the P4 Irving Vincent motor was an undersquare longstroke version…

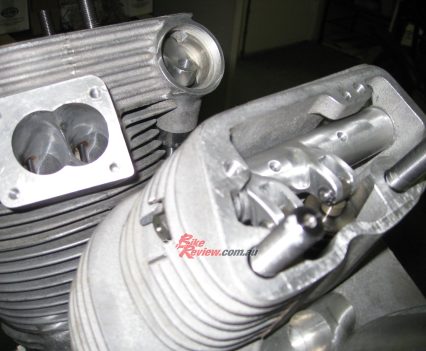

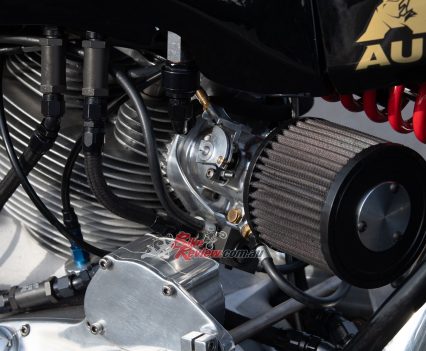

At that early stage of its evolution the P4 Irving Vincent motor was an undersquare longstroke version of the brothers’ externally faithful recreation of the 50° V-twin high-cam OHV Vincent dry-sump motor, measuring 92 x 97.7 mm for 1295 cc. The plain-bearing crank and Carrillo rods were both made in EN26 steel, with Nikasil-bore cylinders housing JE pistons running a hefty 13:1 compression – methanol was and still is the permitted fuel of choice in the Period 4 class, whereas in moving up to the P5 category the Horners had to switch to petrol. “Methanol gives us more torque, but not so much more horsepower,” says Ken Horner.

“In terms of cam profiles and combustion chamber design, we just treat it as one-quarter of a V8 Supercar motor.”

While the heads fitted to the test bike then were the original-spec design with Vincent’s stock 65° included valve angle, Ken Horner had already designed new big-port cylinder heads for the 1600cc motor featuring a much narrower 50° valve angle. Both had short 4140 steel pushrods, roller-bearing cam followers, a revised rocker system, and a vernier cam timing adjustment, all aimed at producing greater power more efficiently. “In terms of cam profiles and combustion chamber design, we just treat it as one-quarter of a V8 Supercar motor,” said Ken Horner. “That way we can plug into the acquired knowledge of all the many people we know who work on those engines.”

The Irving Vincent roller-bearing cams were designed by Melbourne-based Eric Gaynor, an ex-Cosworth engineer who worked alongside Phil Irving…

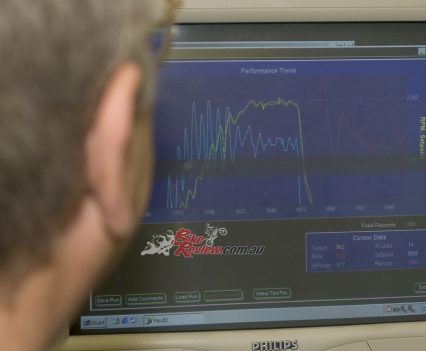

So, the Irving Vincent roller-bearing cams were designed by Melbourne-based Eric Gaynor, an ex-Cosworth engineer who worked alongside Phil Irving at Repco-Brabham before moving to V8 Supercars, with carburation initially provided back then by a pair of 45mm Gardner flatslides incorporating the powerjets actually pioneered on Gardner carbs in the 1960s, mated to twin remote SU float chambers. The day before I got a chance to try out the result, this motor had delivered 130 bhp at the crank at 5,800rpm on the KHE dyno which Ken had installed in his Hallam factory specifically so he could develop the Vincent engine.

“The day before I got a chance to try out the result, this motor had delivered 130 bhp at the crank at 5,800rpm”…

That’s some going for a pushrod V-twin with just two meaty titanium valves per cylinder – a 1.9in inlet (48.25mm) and 1.7in (43.20mm) exhaust, and with a predictably massive 115 ft-lb/155Nm of torque peaking at just 4,600rpm. “But we had to completely redesign the oil system to produce this kind of power reliably,” said Ken. “Phil Irving used to say that the Vincent’s lubrication was so poor – and he took the blame for it – that if you could see inside when it was running, you’d see sparks coming from the cam lobes! We had to make sure we pumped a lot more oil than back then, especially with the plain-bearing crank.”

The Horners did this by installing a self-designed self-made two-stage oil pump in front of the engine, where the magneto normally sat on the original motor, which took care of both pressure and scavenging functions. At the outer end of the shaft driving the pump was an ignition trigger linked to a specially-adapted ECU from MoTeC – another Melbourne-based export leader, whose products were already ubiquitous in BSB and World Superbike – powered by a 12v battery mounted in the tail of the bike. Incorporating a datalogger, this engine management system was infinitely adjustable, and allowed the brothers to map in a range of ignition curves to suit different tracks and applications – solo use, or sidecar – running around 26° of advance.

“This meaty dry sump motor was installed in a modern chrome-moly replica of a period Vincent spine frame”…

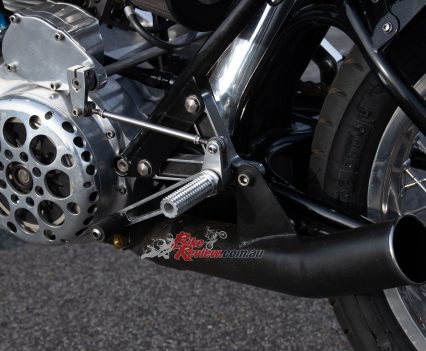

“It was pretty extensive overkill for what we’re doing, but gave us the basis to take the project to the next level with fuel injection,” said Ken Horner. Transmission was a five-speed gearbox based on a Quaife cluster, entirely cut on the KHE CNC machines, with an RD350LC Yamaha selector mechanism (“If it works, who cares where it comes from?” asks Barry) matched to KHE selector forks and drum, and a dry triple-plate sintered bronze AP clutch, with a straight-cut gear primary drive replacing the original Vincent triplex chain.

This meaty dry sump motor was installed in a modern chrome-moly replica of a period Vincent spine frame, with the three-litre oil tank incorporated in the backbone, and a 38mm Ceriani fork fitted with Kawasaki motocross dampers and Öhlins springs, set at an angle of 25° in replacing the original Vincent Girdraulic blade forks. This delivered a 56.5in wheelbase (1435mm in metric money), with 100mm of trail, resulting in a 52/48% distribution of the original Irving Vincent’s 185kg dry weight.

Rear suspension originally came via a fully-adjustable Öhlins monoshock, since replaced by a specially developed K-Tech unit, fitted to a traditional Vincent cantilever swingarm that’s a replica of the one fitted to an original D-series Rapide, says Barry. At that stage there were initially cast iron disc brakes all round, made in-house by KHE, with twin 320mm front rotors and a 280mm rear, all gripped by twin-piston Grimeca calipers. But the rear disc was later replaced by an SLS 200mm drum brake off a Ducati 860GT to meet P4 rules, and the 18-inch Akront alloy rims laced to a Honda front hub and a Norton rear were shod with Avon racing tyres.

It’s always nice to be able to say I told you so – but’s that just what I can do after riding the first ever Irving Vincent solo back in 2006, before it had even started its first race. After sampling the bike in barely completed form, I wrote that “I reckon the Honda fours that currently dominate Aussie Post-Classic racing better get ready for some serious competition – because the Irving Vincent 1300 in the right hands just might be a potent threat to that Oriental supremacy. Just as Phil Irving would have liked it to be…..” History and the record books show that to be true – which made it all the more pleasant to be able to sample the very same motorcycle once again 16 years later almost to the day at the same track, at the 2022 Broadford Bike Bonanza.

In the meantime, it had become the bike to beat in the P5 class Down Under, before being parked in the spacious Irving Vincent ‘Museum’ inside the KHE factory while Ken and Barry focused on the eight-valve 1600cc bike on which Beau Beaton won the seven-round 2015 Australian ProTwins/Nakedbike Championship, defeating fields stacked with Ducati Panigales and Aprilia RSV Tuonos to wrest the title from reigning champion Angus Reekie’s importer-backed KTM 1290 Super Duke R.

Mission accomplished, the Horners decided to return to their roots and dust off Old Faithful, then put it back to P4 spec while incorporating all the lessons from the engine development that had been undertaken on their other bikes in the meantime. That way, by running it on petrol, they’d be able to compete in both P4 and P5 classes at the same meeting, as Beau Beaton had done the weekend before my ride, winning all eight races in the 2022 Australian Historic Road Racing Championships held at South Australia’s McNamara Park – then driving the Irving Vincent Sidecar to four more wins, together with passenger Noel Beare. Busy boy, Beau! Oh – and he also set a new lap record in each of the three classes he won the Aussie title in….

“This has resulted in crankshaft horsepower being raised substantially from 130 bhp at 5,800rpm on the old motor to 157 bhp at 7,000 revs today”…

Updating Old Faithful meant not only fitting the big-port two-valve cylinder heads off the 1600cc Daytona motor, complete with better-breathing flatter 50° valve angle, but increasing titanium valve sizes to a massive 2.15in/54.62mm inlet and 1.65in/41.90mm exhaust, and using US-made PSI dual springs. This was made feasible by altering the original 92 x 97.7 mm longstroke dimensions to a 100 x 82.5 mm short-stroke format via specially-made full-skirt JE pistons mounted on the same Carrillo steel rods – so providing space for the bigger valves, as well as increasing safe peak revs to 7,200 rpm.

This has resulted in crankshaft horsepower being raised substantially from 130 bhp at 5,800rpm on the old motor to 157 bhp at 7,000 revs today, and while there’s only a small overall increase in torque to 159 Nm/117 ft/lb at 6,500rpm compared to 157 Nm/115 ft/lb at 4,600rpm, there’s an even broader spread of that substantial grunt. However, the biggest change you immediately notice when you ride this motorcycle, which while it wasn’t exactly wimpish before, very definitely now has hair on its chest at almost any revs, is the Hillborn mechanical fuel injection which the Horner brothers have now fitted, with twin 48mm throttle bodies made in the KHE machine shop.

“However, the biggest change you immediately notice when you ride this motorcycle, which while it wasn’t exactly wimpish before, very definitely now has hair on its chest at almost any revs”…

I’ve ridden several racebikes fitted with mechanical FI, and they all had the same characteristics – a lighter, super-responsive throttle that was often too much of a good thing, thanks to more power being available sooner via a fierce initial pickup, which in the absence of TC invited the rear tyre to unhook itself. This is because these packages were developed for racing cars, where four wheels mean that you can afford to have an on/off throttle response, and all or nothing power delivery.

“This was certainly the most demanding to master of all the several different such bikes produced by the Horner brothers…”

I’ve never crashed one so far, touch wood, and fortunately still haven’t after riding the Hillborn-equipped Irving Vincent – but this was certainly the most demanding to master of all the several different such bikes produced by the Horner brothers that I’ve been honoured to ride down the years, because with the Hillborn FI fitted it has the same power as the Irving Vincent’s Japanese Superbike-beating P5 engine spec, but housed in the less amenable P4 chassis.

That’s despite the Horners addressing the rideability problem by fitting a variable ratio twistgrip to try to make the throttle response a little more amenable off the bottom, and it’s true that leaned over in slower turns, like the horseshoe right behind the Broadford paddock, I could feed the power in initially fairly controllably for the short squirt to the final off-camber left-hander running on to the main straight. But there I had to be really cautious, because besides a drum rear brake the P4 class stipulates 18-inch wheels, and feeding the Irving Vincent’s acres of torque to the tarmac in a turn like that through a skinny 130/65 rear tyre calls for a mixture of skill and bravery that takes time to acquire.

“Feeding the Irving Vincent’s acres of torque to the tarmac in a turn like that through a skinny 130/65 rear tyre calls for a mixture of skill and bravery that takes time to acquire…”

OK, Beau Beaton would surely have delighted in powersliding the Vincent on to the front straight there, but while I managed several times to catch the rear wheel drifting when I got too excited with my right hand, I also know my limits, which are much lower than his, making powersliding the bike out of turns definitely not an option for us lesser mortals! Interestingly, Beau uses an Avon AM23 rear, but a super-skinny 110/80 Bridgestone Battlax front tyre I’d never used before, but which I couldn’t fault for grip in places like Broadford’s uphill Turn One, where you must use quite high turn speed to maintain momentum for the launch down the undulating main straight.

Acceleration is so emphatic that the trick of riding the P4 EVO Irving Vincent in something approaching anger is to try above all to pull it as upright as possible exiting a turn, before pulling the trigger via your right hand to max out drive from the meaty motor. However, you must beware getting too impatient to do this, as I almost found out the hard way by starting up the stairway to highside heaven a couple of times in exploring the outer realms of grip from the rear Avon. Both times I caught the slide before it got terminal, but for sure the rear WM4/2.50in rim is too narrow to spread the 130/65-18 tyre sufficiently well to give it a flatter profile which would deliver a bigger footprint, and let you use all the tyre to harness that torque. A 600 Supersport delivering a little less power than the Irving Vincent has a 180/55 chunk of rubber via which to lay it down….

But another problem is that the car-derived Hillborn injection doesn’t like part-throttle openings, so the hot tip is to use one gear higher in a bend and ride the high, wide and handsome route round turns, then lift it up to use the fat part of the tyre to accelerate hard out of the corner. Of course, this then exposes you to people trying to stick their front wheel up the inside to outbrake you into the apex – as, ahem, my ‘teammate’ Cam Donald did one lap on another Irving Vincent, only to have to abort mission when he realised I was committed to the turn. No problem – we both survived!

But the Vincent has so much grunt above 2,000rpm that surfing the torque curve like this is definitely the best way to ride it, even if it means you’re covering extra track mileage. You can afford to do this as that way you can get harder, sooner on the throttle to drive out of the bend, though you must get ready to use the back brake to stifle second and third gear powerwheelies at birth – well, unless your name is Beaton, and that’s all part of the BeauShow!

“This isn’t the point-n-squirt bike you might expect it to be with all that torque, but a well-balanced, fine-steering package…”

The Horner-built motor is incredibly smooth for a 50° V-twin with such big pistons, and no balance shaft – it runs like a turbine in pulling hard from two grand on the Sport-Comp tacho to the 6,500rpm mark where I shifted up – the engine’s safe to 7,200rpm, say the Horners, but really there was no point running it that high, as there’s more than enough usable midrange performance lower down the dial.

Stopping the bike at the end of both straights was very emphatic, with no sign of the brake fade I’d experienced the first time I rode this very bike there 16 years earlier, but instead great bite from the twin front discs made by KHE, now downsized to 300mm and gripped by those ultimate 1970s stoppers, AP-Lockheed’s two-piston calipers. But even with the slipper clutch you must be careful not to use the rear brake too hard to avoid chattering the rear wheel via the massive inertia under engine braking of such a big twin. You must learn to ride such a mega-motorcycle in a very measured manner – do so, and it’ll pay off in lap times.

Great stopping power on the P4 bike, with no signs of fade, even with a slipper clutch fitted, the AP calipers do the trick.

But, that aside, the Irving Vincent fully lived up to its promise on paper, with extra performance on tap via the 10kg loss in weight versus the last time I rode it – it now scales 175kg dry, split 52/48% for an ideal forward bias for maintaining turn speed. This isn’t the point-n-squirt bike you might expect it to be with all that torque, but a well-balanced, fine-steering package that with a 1435mm wheelbase is just long enough to be stable over bumps, while short enough to be agile.

“While the spring on the rear K-Tech shock is pretty stiff to cope with all that mega-torque under acceleration, it still felt reasonably compliant”…

The born-again Aussie Vincent feels relatively tall and quite rangy when you first straddle it, and there’s a good stretch across the 22-litre fibreglass fuel tank to the high-set but wide-spread clip-ons bolted to the top of the 38mm Ceriani fork legs. These have been dropped around 60mm through the upper triple-clamp to sharpen the steering, and improve front end weight bias for extra grip laying the bike into turns. It works, too – the Vincent isn’t exactly light steering, but the wide ‘bars deliver good leverage for hustling the bike through Broadford’s tight bends.

While the spring on the rear K-Tech shock is pretty stiff to cope with all that mega-torque under acceleration, it still felt reasonably compliant over Broadford’s bumps, although the stiff setting helped deliver some impressive second-gear power-wheelies each lap out of Turn One. And the cocktail of ingredients in the 38mm forks worked very well, with what was probably the best feedback from the front tyre through a set of Cerianis that I’ve ever experienced. I could definitely feel what the front Bridgestone was doing with the bike cranked hard over round the bends leading on to the two Broadford straights.

“Probably the best feedback from the front tyre through a set of Cerianis that I’ve ever experienced’…

The five-speed gearbox with un-classic left-foot race-pattern shift works well enough, but it had at least one ratio too many for a tight track like Broadford, where I only used four gears on my rides. On the quite tall gearing, I did need to use bottom gear twice per lap, but there was no big drama about going through neutral, as on many big twins on the move. Three gears might actually have been enough if we’d re-geared it, thanks to the wide spread of power and the fact I could hold a gear through Broadford’s infield with the flash of the bright red junior searchlight on the dash at 6,500rpm to remind me to get ready to shift up.

“Getting the bike motoring down Broadford’s pair of straights was incredibly intoxicating, meaning I didn’t want to stop after any of my 15-minute sessions on the bike!”

Getting the bike motoring down Broadford’s pair of straights was incredibly intoxicating, meaning I didn’t want to stop after any of my 15-minute sessions on the bike! Getting early on the gas thanks to the feedback from the tyre sent the Irving Vincent rocketing out of the turn to the staccato accompaniment of that lazy-sounding exhaust, that’s quite at odds with the speed at which it’s travelling, before thundering down the straight like a jet-propelled cannonball. All we needed were a fleet of fours to leave struggling in its wake….

To transform the red P4 longstroke bike I sampled 16 years ago into the black short-stroke racer I rode at BBB 2022, the Horners used the same heavy duty crankcases with provision for fitting an ND starter motor and alternator for the putative Irving Vincent streetbike that so many people have been trying for the past 15 years to persuade them to build. So here we are post-Covid, with things almost back to normal – what chance of an Irving Vincent roadbike, boys?

“So here we are post-Covid, with things almost back to normal – what chance of an Irving Vincent roadbike, boys?”

“We keep talking about it,” says Ken Horner, “but we’ve got to convert this to actually doing something, because people are getting frustrated. We get all these inquiries on the internet, many of them from impecunious enthusiasts, but there might be one person in there with a few million dollars who wants to have three of them, and we don’t know who he is! We’ll never take a deposit off anybody, and all transactions will be built to order – we don’t need deposits to fund the project. But Barry and I do both want to do a road bike – we’ve been talking about it for so long, we know we now have to actually do something about it. Watch this space – honestly!”

Barry and Ken with their families, at Broadford in April this year, a couple of Aussie legends with an incredible story.