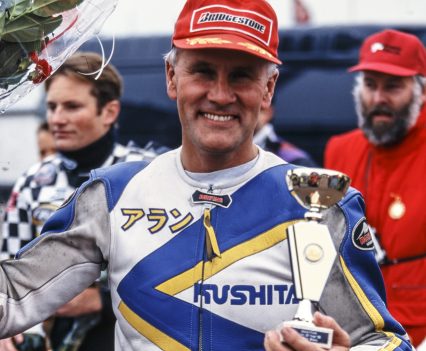

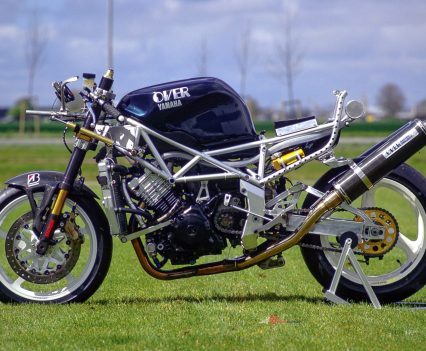

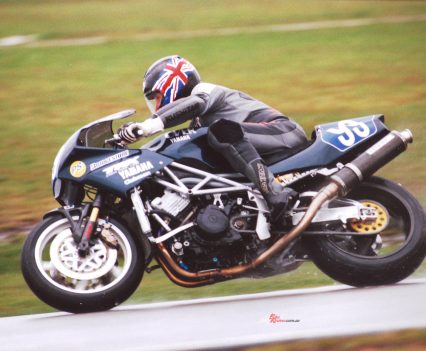

AC recalls racing Over Racing's TRX850R in Europe and Daytona and how its success paved the way for Euro and Aussie sales. Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura & AC Archive

We’ve brought you Sir Al’s TRX850 proddie test, now his Over Racing TRX850R racer. Born as a Japan-only oddity, the TRX became a giant-killer when Cathcart and Over Racing delivered unlikely results on two of the world’s most hotly contested series.

After its debut as a Japan-market only model in 1995, Yamaha Motor Europe’s (YME) Amsterdam HQ couldn’t decide if there was a place for the TRX850 in western Europe, which in those days was Sportsbike Central. But YME Marketing Manager Lin Jarvis came up with a bright idea. Yes, the same Lin Jarvis who later became CEO of Yamaha Racing’s MotoGP effort who, before he began nurturing its GP team into serial World title-winners by recruiting Valentino Rossi, Jorge Lorenzo and Fabio Quartararo, first recruited me.

Lin’s big idea was to get Over Racing in Japan to build a reasonably tricked-out TRX850R racer, then give it to me to race that year in Europe’s leading ProTwin events. Even if I didn’t win anything, that’d still get the bike out there and people used to seeing it in action as a counterpoint to all those Italian V-twins. Then hopefully their response would help YME decide if there was a market for it in Europe. And that’s how I got to be Trixie’s blind date!

“Lin Jarvis’ idea was to get Over Racing in Japan to build a reasonably tricked-out TRX850R racer, then give it to me to race”

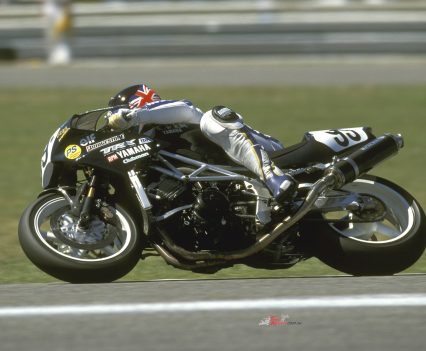

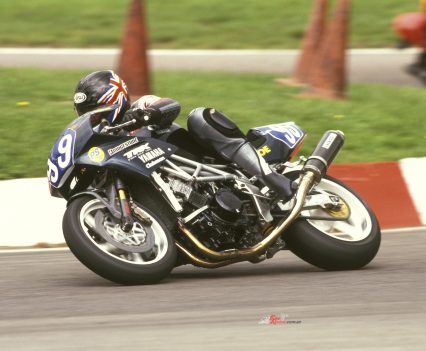

Over Racing was thus commissioned to build such a racebike in just six weeks, before air-freighting it to Europe in time for the first round of the Dutch Open series at Assen on Easter Monday, April 16. My blind date with Trixie was just that: fresh off the plane from Japan earlier that week, I’d never even sat on the bike until the first qualifying session at Assen, much less tested it or set it up. But Over boss Kensei Sato flew over with Trixie, together with his chief race mechanic Ume Umemoto, to look after it for the first two races. Kensei’s expertise circumvented that setup problem, since I’d been racing his bikes in Japan for the previous five years, so we had some base settings to work with.

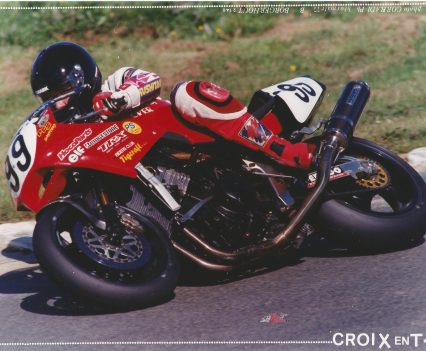

In the first dry session at Assen I made sixth on the grid out of the 36 qualifiers, before the heavens opened and it rained for the next two days! That at least gave me some wet-weather practice on the TRX850R in the second session, which revealed one big bonus: this was an incredibly easy bike to ride in the rain, especially when combined with the excellent grip of Bridgestone’s super new rain tyres. This allowed me to win the TRX850R’s debut race by the embarrassingly large margin of 25 seconds, from Dutchman Marcel Lamers’ 900 Ducati two-valver, and Germany’s Rolf von der Weiden on his BMW Boxer. Way to go, Trix!

Winning major Battle of the Twins races ahead of 60-bike fields on GP circuits like Spa-Francorchamps and Assen was a real buzz, as well as proving the significant potential of the TRX850R for performance tuning for road or track. Out of a total of eight International ProTwins races in Europe that season, we won five of them, finished second and third once each, and DNF’d just a solitary time in the final race of the year at Assen, after qualifying on pole for the seventh time out of eight in all.

“Out of a total of eight International ProTwins races in Europe, we won five of them, finished second and third once each and DNF’d just a solitary time”

Finishing 11th at Assen would have been good enough to win the Dutch Open title, but sadly, that didn’t happen. After grabbing the lead tragedy struck when I tried to shift gear down the back straight but couldn’t find the lever! A 10-cent split pin had broken in the gear linkage, leaving the lever dangling, and Trixie stuck in third. It was the cruellest disappointment of my racing career.

Yamaha Europe were very understanding, despite several of their staff making the trip to Assen complete with Yamaha flags to watch me hopefully clinch the title. But even so, I wasn’t prepared for what happened next. Their PR soundings had been so positive that they decided to import the TRX850 into Europe for 1996 – and while I’m sure my success with Trixie had only played a small part in that, they decided to reward me for my efforts by paying for me to take Trixie to Daytona for Cycle Week 1996. Yes!

Back went one of our two engines to Japan for Over to refreshen it then ship it to Florida, while my race mechanic Alistair Wager race-prepped the bike fitted with the other motor, before moving to the USA to run the Saxon-Triumph team’s Formula USA campaign with Scott Zampach. My focus shifted to teaming up with Brook Henry of Vee Two Australia to contest World Superbike’s FIM Supermono Cup support championship, and the BEARS World Series, this time with a factory-supplied Bimota DB2R with Vee Two Australia motor. But Brook was up for looking after Trixie at Daytona for me, figuring it’d entail little more than topping up the fuel tank and pumping up the tyres. Little did we know…

The two-day AHRMA Cycle Week opener saw the Formula 1 ProTwins race held on Monday, essentially for Modified Production motorcycles, with the Open Twins race on Tuesday for anything with a twin-cylinder four-stroke motor. That meant no Brittens in the F1 race – but conversely there were platoons of Ducati homologation specials, including several of the new 916SPS Foggy street replicas. Still, with Trixie trapped at 258km/h [exactly 160mph] at Mettet the year before, maybe I wouldn’t be totally smoked. But because of time constraints there’s a morning practice but no qualifying for AHRMA races, with grid positions for the afternoon race decided on the previous year’s points! So I’d have to start from the back of the grid…

“There were platoons of Ducati homologation specials … still, with Trixie trapped at 258km/h [exactly 160mph] at Mettet the year before, maybe I wouldn’t be totally smoked”

I did that anyway, but for a different reason. Halfway through practice, the TRX motor blew on the run down to the chicane – disaster! Trucked back to the paddock, our five-strong team descended on the bike to swap motors against the clock, one of them fortuitously being Norm Williams, the manager of Yamaha’s top dealership in Perth, WA, who’d come over with Brook to spanner the Bimota.

We’d left the spare engine in our Daytona Beach workshop – so that was why the motor blew – but my American mate Jeff Craig ran every red light to retrieve it and made it back to our garage just in time to see the engine leaving the frame. The race was called but Trixie still wasn’t ready, so gloved up and helmeted I went to stand by the pit entrance. The 40-strong field set off on their warm-up lap just as Brook Henry arrived aboard Trixie, blipping the throttle to clear a path, with his Vee Two apron blowing in the breeze. It was game on.

What followed next was the most satisfying race in my 50-year career. AMA rules dictated I start from the back row after missing the warm-up lap, but with no tyre warmers back then I forced myself to take it easy in the infield turns before dialling up the heat on the banking. This was the engine Over had rebuilt for us, and fresh out of the crate it was running strongly, plus I’d done enough laps in practice to know we had the gearing right: Mettet, minus one tooth on the rear to allow for slipstreaming on the bankings – only a half-fairing, remember.

I used every last rev in every gear to claw my way up the race order, until two laps from the end I hit the front, nailing the leading 916SPS Ducati on the brakes off the Tri-Oval banking into Turn 1. When I looked behind four turns later exiting the infield I saw he was already too far back to be able to draft past me, though from there to the flag were the most anxious two laps of my racing life. But Trixie ran cleanly to the finish – job done!

I still have this memory of the guys on the Ducatis I shared Victory Lane with looking at Trixie with this “How-the-hell?” expression on their faces. They weren’t alone: “Alan Cathcart, how on earth did you guys make a dirt bike go so damm fast?” asked announcer Richard Chambers. Well, Richard, Yamaha USA never imported the TRX850, preferring instead to lose millions on the unloved Royal Star V4 cruiser, so you can be forgiven for not knowing one of the best kept secrets in motorcycling…

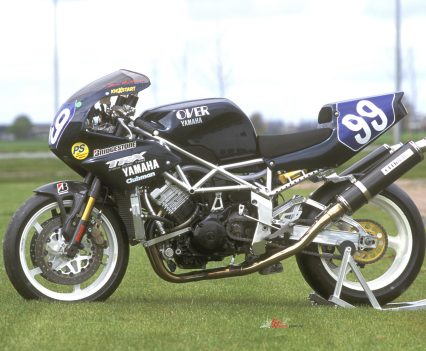

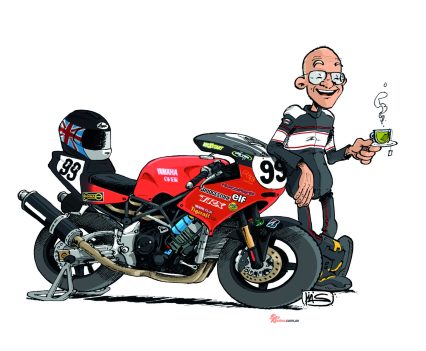

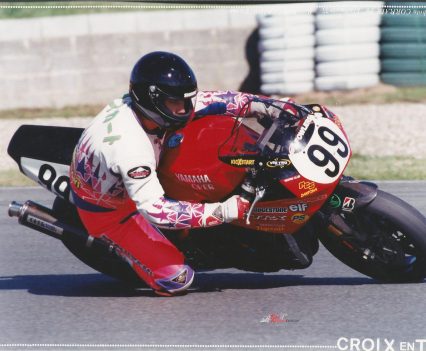

Due to other commitments I raced the Yamaha only a handful more times in 1996, scoring a trio of wins and never finishing off the rostrum. But for 1997 I clinched a deal with Yamaha Europe to contest the inaugural Sound of Thunder World Series on their Over-developed TRX850R racer, which entailed another sortie to Daytona – apparently, beating the Ducatis there the previous year had gone down big time in Japan! Their only condition was that I had to repaint Trixie in the same red-and-black livery as their World Superbike/Supersport race teams. Happy to oblige, gents…

“I clinched a deal with Yamaha Europe to contest the inaugural Sound of Thunder World Series on their Over-developed TRX850R racer”

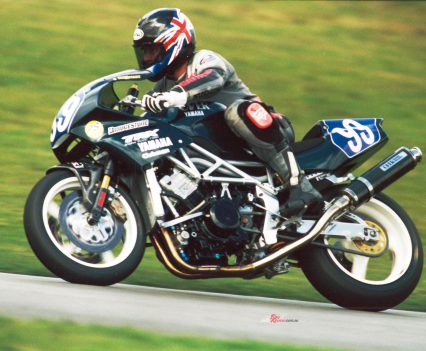

In preparation for the World Series, Yamaha Europe sent both engines back to Japan during the winter for Kensei Sato & Co. to wave their magic wands over them. They arrived just in time for Daytona, and as soon as I rode out onto the Speedway for the first practice session, I knew they’d made a significant improvement in engine performance. Over had not only delivered an extra 6hp at the top end, they’d also fattened the already torquey midrange and, above all, improved engine acceleration and pickup quite noticeably, thanks to the reduced inertia of lighter engine components.

Many detail changes had given the engine more zip than before, allowing us to pull one tooth higher gearing than in 1996 and we were trapped at 272km/h [169mph] on the Tri-Oval, which was some going for a modified budget-priced sports twin roadster with only a half fairing. This gave me some hope as we fronted on the grid for the Open Twins race on the Monday of Cycle Week, versus a field headed by Andrew Stroud’s Britten and containing no less than 14 Ducati desmoquattro Superbikes, three of which would go on to qualify for the Daytona 200 later in the week.

Many detail changes had given the engine more zip than before, allowing us to pull one tooth higher gearing than in 1996 and we were trapped at 272km/h [169mph] on the Tri-Oval, which was some going for a modified budget-priced sports twin roadster with only a half fairing. This gave me some hope as we fronted on the grid for the Open Twins race on the Monday of Cycle Week, versus a field headed by Andrew Stroud’s Britten and containing no less than 14 Ducati desmoquattro Superbikes, three of which would go on to qualify for the Daytona 200 later in the week.

With her half-naked looks and slant-twin motor in full view, Trixie must have looked pretty incongruous, a modified roadster against these tricked-out, more potent race replicas. But this time, though, I had a second-row grid position and took full advantage of it to grab second place behind Stroud’s Britten going into the first turn: the Yamaha was so tractable and smooth in terms of power delivery, it was always great off the line. Up onto the banking the first lap and the Britten just motored away from me – as expected – but after I got a good drive out of the infield, just one Ducati came powering past me, Jeff Jennings on his new 955 Corsa factory-built Foggy Replica.

One vital Daytona must-do is always to give yourself lots of braking room at the chicane on the first lap, when with a full fuel load and often a big draft from a field of bikes in front of you, it’s way too easy to go in too deep and crash. I have my lap-one brake marker there for each bike – and stick to it religiously – and that’s what I did this time to be rewarded with the sight of Jennings coming as close as possible to having a major accident in front of me on the entry to the chicane, and getting away with it!

Read Alan’s TRX850 production model Throwback Thursday article here…

He missed the entry, hit the dirt on the outside, crossed the track in front of me… and apparently somehow saved it! I say ‘apparently’ because I squeezed through and only saw part one of the incident, but I looked behind exiting the chicane and saw he’d held everyone else up, so I now had a gap back to third place.

I knew this was my chance to make a break against the faster Ducatis, so I put my head down and went for it, riding the next three laps as hard as possible, using every last rpm on the banking and drifting the rear Bridgestone in the infield. It worked: the gap to Jennings (who’d regained third) stabilised at four seconds and I ran out the 10-lap race in second place after a satisfying ride.

To be beaten by an exotic racebike like the Britten was no disgrace. But for a modified street bike like the TRX costing $10k new back then – with another $10k of Over tuning parts added – to beat a fleet of the world’s top twin-cylinder $30k+ customer Superbikes said a lot for Trixie’s design. In fact, my best race lap in the Open Twins race would have qualified my carburetted TRX850 54th on the grid out of the 80 starters for the 200-mile Superbike later that week.

“For a modified street bike to beat a fleet of the world’s top twin-cylinder customer Superbikes said a lot for Trixie’s design”

However, this Open Twins race was really just the warm-up for the main event, the 50-mile Sound of Thunder World Series 15-lap round held the next day, for which Andrew Stroud on the works Britten was joined by Mike Barnes on a brand-new customer version: double trouble! Trixie and I beat Stroud to lead into the first turn after he pulled a monster wheelie (probably on purpose!).

But he and Barnes soon breezed past us, en route to a Britten 1-2, so with a safe third place in prospect, I kept a 15-second cushion to fourth-place Mike Gage on a factory-assisted new Triumph T595 Daytona. It set us off to a good start in the struggle to earn the 1997 Sound of Thunder title.

“I won the other four rounds in the six-race series in France, Belgium and Britain, to give Yamaha Europe and Trixie a title at last”

And that’s indeed what happened, with a series of race wins in Europe interrupted only by a third place in the Assen round in June after being slowed while in second place by an ignition fault which mysteriously imposed a 6000rpm revlimit on the engine! But I won the other four rounds in the six-race series in France, Belgium and Britain, to give Yamaha Europe and Trixie a title at last. YME had a nice way of saying thanks – which is why the Over Yamaha TRX850R has been locked up safe and sound in my garage for the past 30 years. We still enjoy a date together from time to time at a nearby race track, though: got to stay tuned up for Vintage ProTwins when it happens!

Yamaha TRX850R Over Racing Specifications

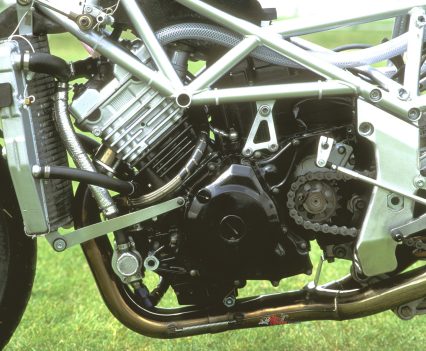

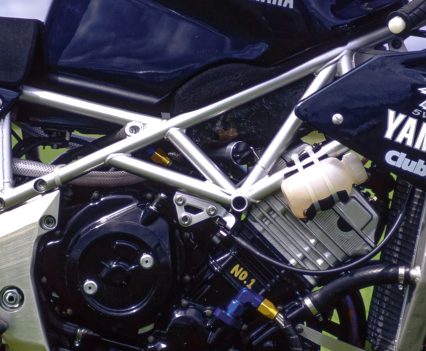

Engine: Water-cooled DOHC 10-valve parallel-twin four-stroke with chain camshaft drive, 270° crankshaft throw, 90.5 x 67.5mm bore x stroke, 12.5:1 compression, 868cc, 2 x 41mm Keihin FCR flat-slide carburettors, Yamaha CDI with 12v battery, six-speed Over close-ratio gearbox, multiplate oil-bath clutch.

Chassis: Tubular steel spaceframe with cast-aluminium swingarm pivot plates, engine used as fully stressed member, fully adjustable 41mm Showa inverted telescopic fork modified by Over Racing, braced extruded aluminium swingarm with fully adjustable Öhlins monoshock and rising-rate link, 23.5º rake, 94mm trail, 1420mm wheelbase, 171kg dry weight, 52/48% static weight distribution, 320mm Brembo cast iron floating front discs with four-piston Brembo calipers, 185mm Yamaha fixed steel rear disc with two-piston Brembo caliper, Marchesini cast aluminium wheels (3.75in and 6.25in), Bridgestone 125/595-17 front and 190/640-17 rear radial tyres.

Performance: 121bhp at 8750rpm (at gearbox), top speed 272km/h (169mph) at Daytona 1997, year of construction 1995 (updated 1997), owner when raced Yamaha Motor Europe NV, Amsterdam, Netherlands.