Two decades ago we lost one of the most innovative individuals of the motorcycling world. Alan tells us about the amazing life of Claude Fior... Words: Alan Cathcart Photos: AC Archive

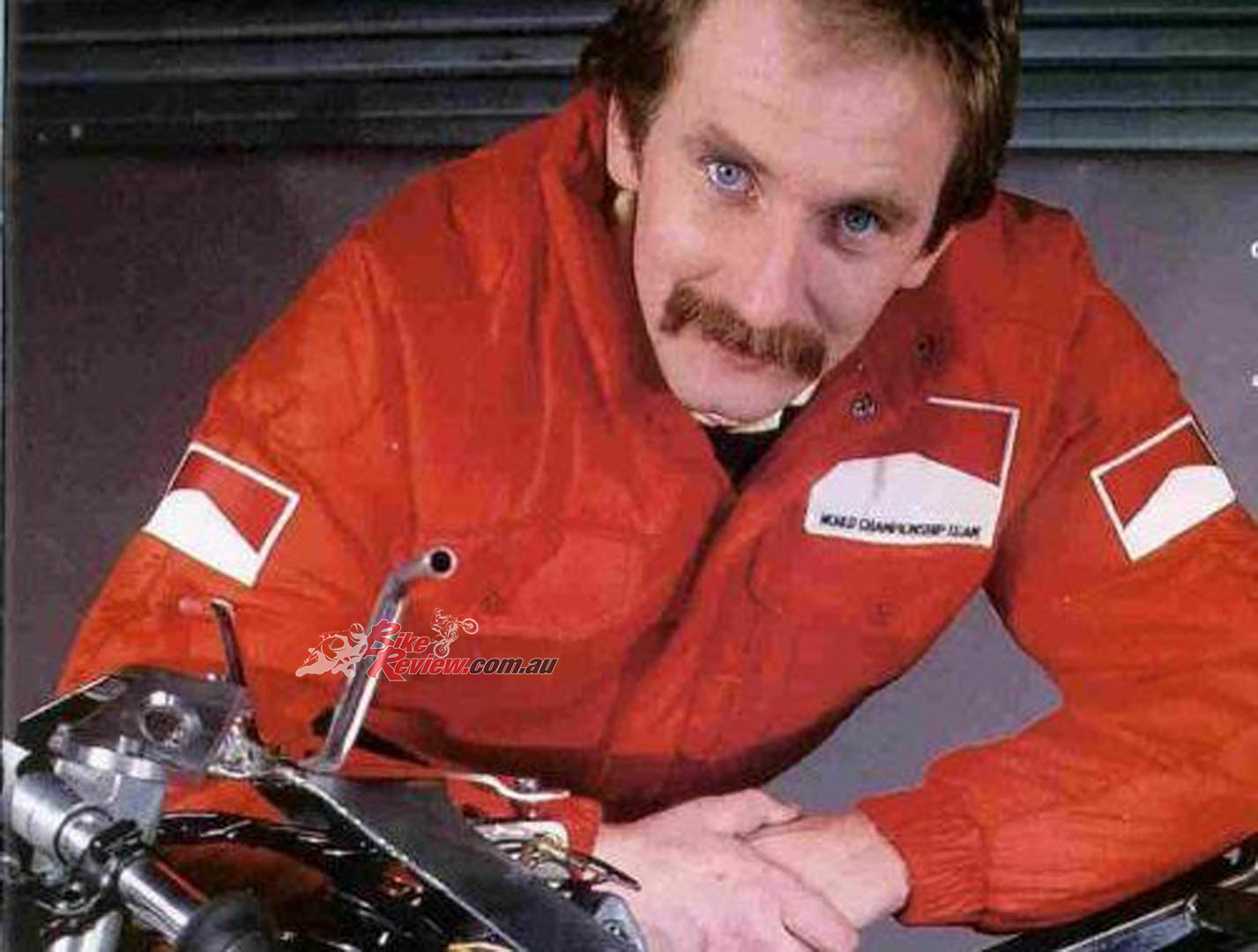

Just over twenty years ago, on December 13, 2001, the motorcycle world lost one of its greatest free thinkers and most innovative engineers, when 46-year old Frenchman Claude Fior was tragically killed at the controls of his self-built private plane…

With Fior’s death passed a man whose boundless creativity, matched by an appetite for fun, had graced the Grand Prix paddocks for more than a decade in the 1980s and ’90s, and whose capacity for original thought marked him as a radical force in alternative motorcycle design.

Read Alan’s test of the Fior 500-4 GP bike here...

The distinctive Fior wishbone front suspension design which dates back to 1976, has since been copied by designers all over the world, from Britain to New Zealand, Germany to Japan, and in the form of its volume-production derivative, BMW’s K-series Duolever fork, represents the most practical and widely accepted alternative to conventional motorcycle front suspension design, yet brought to the streetbike marketplace.

Nogaro lies in the Armagnac region of southern France, the Gascon homeland of the Romantic idealism which produced D’Artagnan and his swashbuckling Three Musketeer mates, who in Hollywood scripts as well as Alexander Dumas’ novels became renowned for battling the dark forces of established order.

Nogaro not only hosted the testing and development area for Fior’s designs. It was also Claude’s home and the location of his tragic accident.

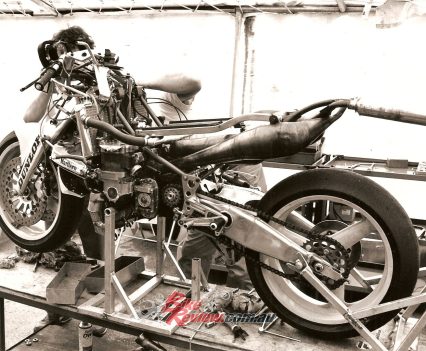

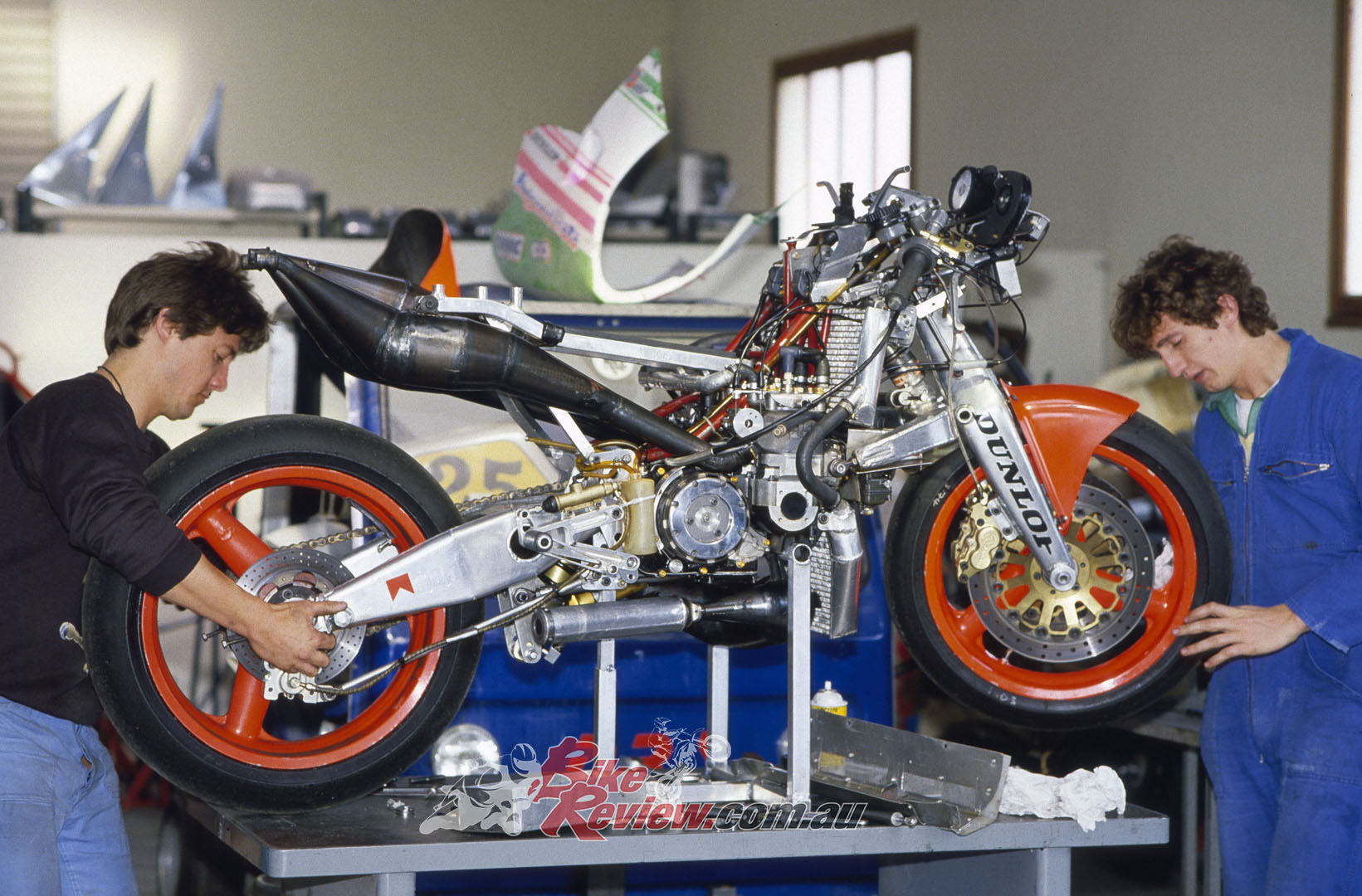

A foe of convention and normality just like D’Artagnan, Claude Fior’s chosen weapons were not the sword or the rapier, but the pencil and the arc-welder, with which this unsung visionary created a proud portfolio of self-designed motorcycles which, despite budgetary obstacles, repeatedly proved the worth of his radical ideas out on the racetrack. The Fior Concept workshop beside Turn Nine of the Nogaro GP circuit gave constant expression to the capacity of Claude Fior – universally known as ‘Pif’ – to match innovation with artistry, and combine quality of construction with a devilish flair for the unlikely.

After beginning his career as a mechanical free-thinker back in 1964 at the tender age of nine, when he converted his elder brother’s front wheel-drive Solex moped to rear-drive operation by moving the engine from its usual shopping-basket location in front of the handlebars to a possibly more rational one above the rear wheel, Claude Fior spent two years after leaving school working as a mechanic for a French Formula 3 racing car team.

Already a highly skilled welder – he constructed the prototypes of all his many creations entirely himself throughout his life – he soon acquired a reputation as a top aluminium fabricator, leading him in 1976 at the age of 21 to set up his own such business in his home town of Nogaro, working as a subcontractor for France’s flourishing racing car industry. But this had just one objective – to support the bike-mad Pif with the means of fuelling his own career as a motorcycle racer.

Claude was already a highly skilled welder by the time he turned 21. However, four wheels didn’t interest him nearly as much as two…

A series of good results in French National events encouraged Fior to aim higher, so in 1978 he moved into World Endurance racing, scoring a series of leaderboard finishes in 1978-79 at major events like the Le Mans and Barcelona 24 Hour races, culminating in third place as a privateer in the Austrian 1000km championship round at Zeltweg in 1980, on his Fior-framed 1000cc Honda.

After racing at Le Mans in 1978 on a Yamaha XS1100, Claude began to pick up on some of the issues bikes faced with a conventional fork setup, beginning his legacy was the Fior suspension setup.

“In 1978 I rode at Le Mans on an XS1100 Yamaha converted from shaft to chain final drive,” Pif explained to me in 1991, “and although we finished second in the Silhouette class, throughout the 24 hours we had constant handling problems with the front-end – it was terribly unstable. After that race I decided I could surely build something better myself, drawing on my experience in the racing car world to produce an improvement on flimsy telescopic forks. La fourche Fior was the result, and after 50 different chassis designs so far for different engines and applications, from the street to the racetrack, I’m still convinced that I’m right. The only reason bikes still use telescopic forks is that motorcyclists are creatures of habit, and none more than racers – they mistrust anything which is new and looks different, even if it works better!”

“The only reason bikes still use telescopic forks is that motorcyclists are creatures of habit, and none more than racers – they mistrust anything which is new and looks different, even if it works better!” said Claude.

Success with the first Fior-Yamaha XS1100, with 8th place in the 1979 Le Mans 24 Hours against all the factory machines, led to the more potent RSC1000-engined Fior-Honda which the Fior/Guy riding duo campaigned with such success in 1980. This had a complete Fior-built chassis, instead of a Fior fork hung on the front of the stock XS1100 frame, and its proven worth led Pif to hang up his leathers to concentrate full-time on chassis design, after producing the first of the series of Fior GP racers, all marked by the same emphasis on light weight and avantgarde design.

This was an aluminium-framed Yamaha TZ250-powered bike which Pif raced himself with some success in French National events, and with his expertise in aluminium construction a timely asset as the era of alloy race frames was dawning, this got noticed by the French Yamaha importers, Sonauto, who commissioned a chassis from him to house a factory OW54 500cc square-four GP engine for Marc Fontan to ride in the 1981 GP season.

The TZ250 caught the eye of the French Yamaha importers, Sonauto, who commissioned a chassis from him to house a factory OW54 500cc square-four GP engine.

But the result was so unconventional that the Japanese factory engineers refused to condone its use in public with one of their engines: the hub-centre GTS1000 Yamaha road bike was still some years away! “Sonauto paid me a good fee for the bike, but I’d have preferred to have done without that, and instead seen it racing,” recalled Pif remorsefully.

“The non-appearance of the factory-engined Fior-Yamaha 500 was always counted as Pif’s biggest disappointment in racing.”

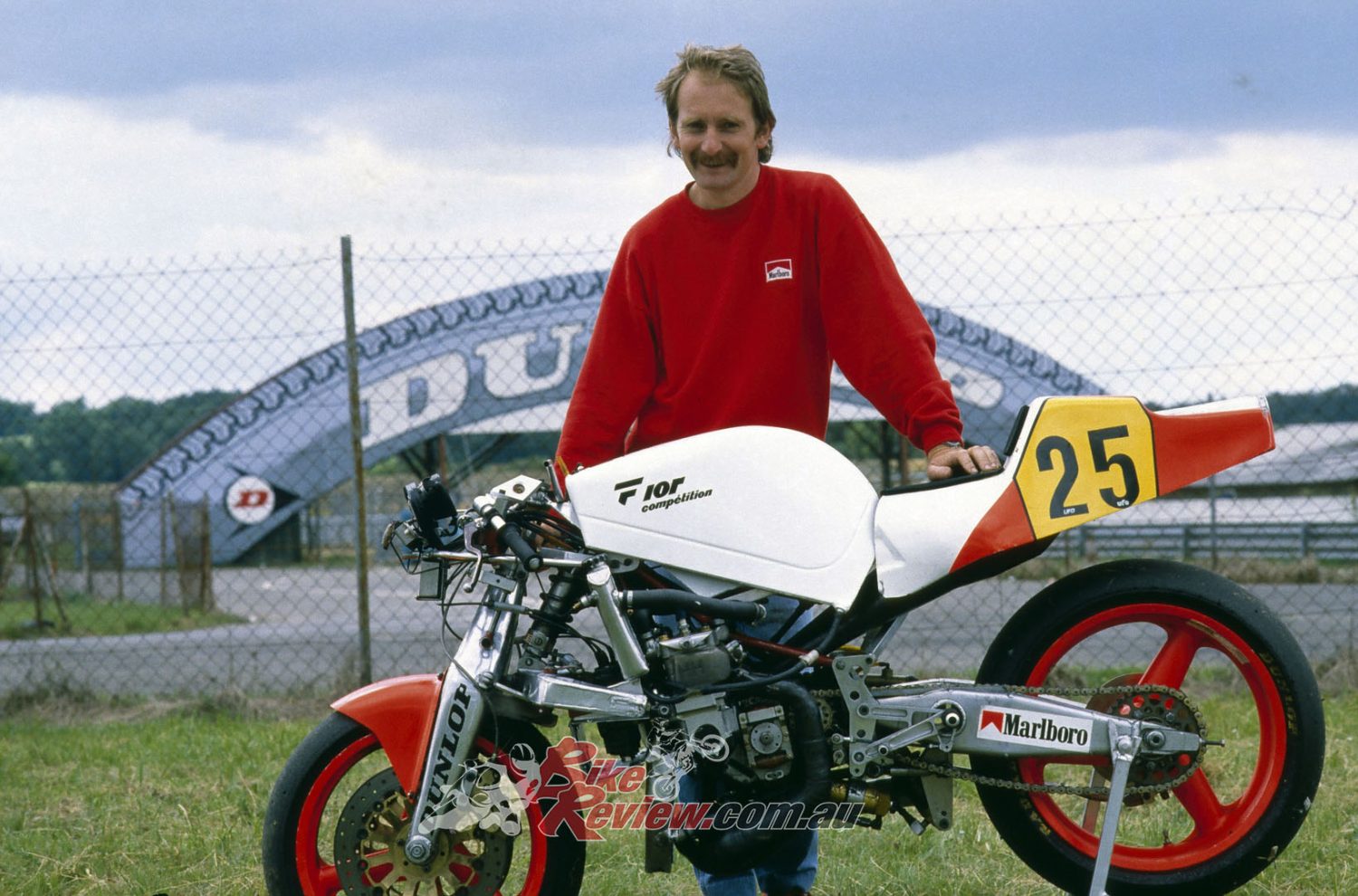

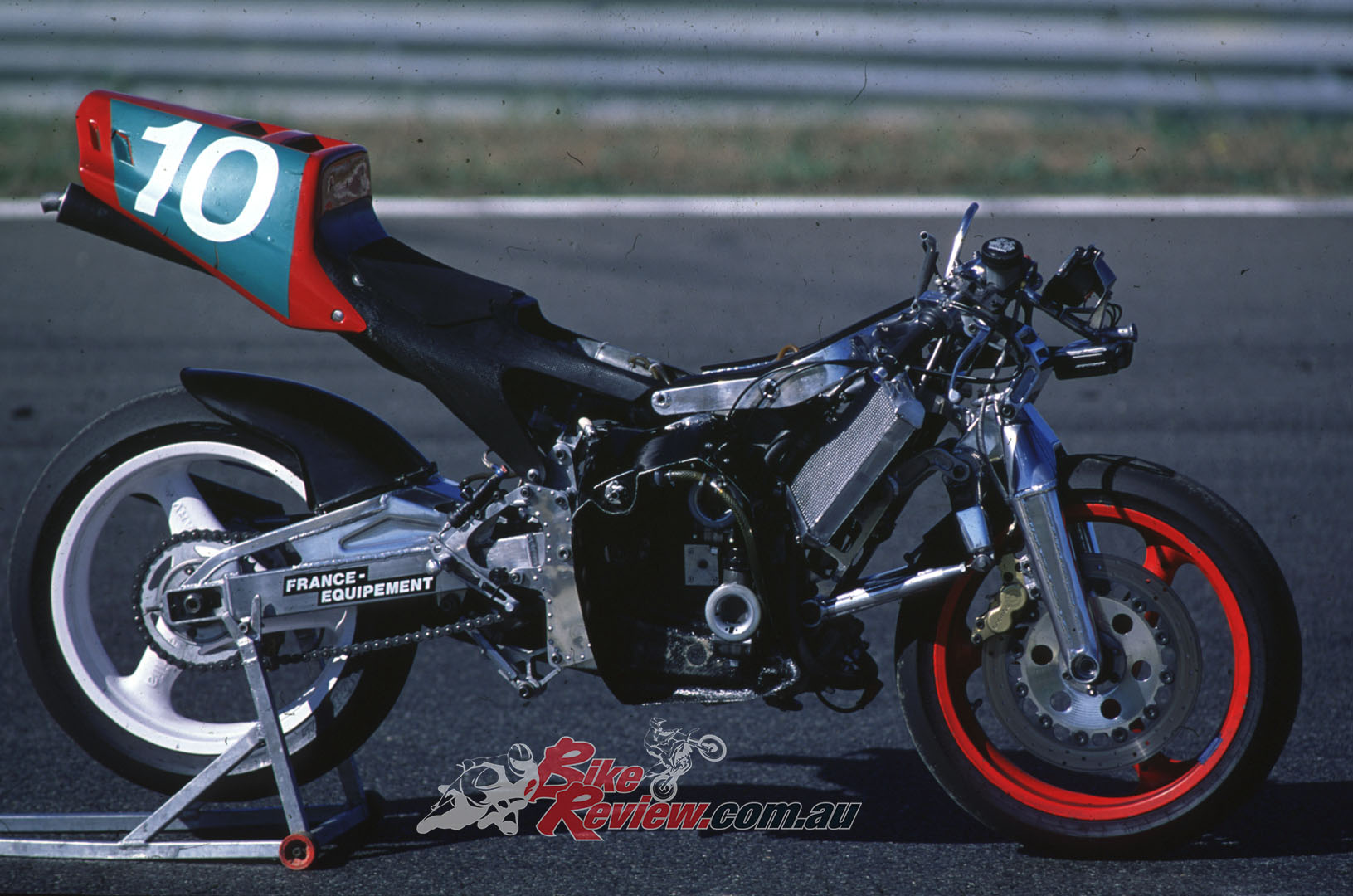

The non-appearance of the factory-engined Fior-Yamaha 500 was always counted as Pif’s biggest disappointment in racing. Still, the money allowed him to construct his own 500GP racers, a pair of Fior-Suzukis built around the RG500 square-four engine, which World Endurance champion Jean Lafond rode in several 500GPs in 1982 – most notably in the French round on home ground at Nogaro, when he qualified on pole for a race boycotted by all the factory riders, on account of the bumpy track and the cramped, decrepit paddock conditions.

Sadly, there was no fairytale ending: Lafond crashed out of the lead on lap 11 en route to victory, handing the win to an equally quixotic entry, Michel Frutschi’s Sanvenero.

Sadly, there was no fairytale ending: Lafond crashed out of the lead on lap 11 en route to victory, handing the win to an equally quixotic entry, Michel Frutschi’s Sanvenero.

Read our Throwback Thursday on the Sanvenero 500 GP Racer here…

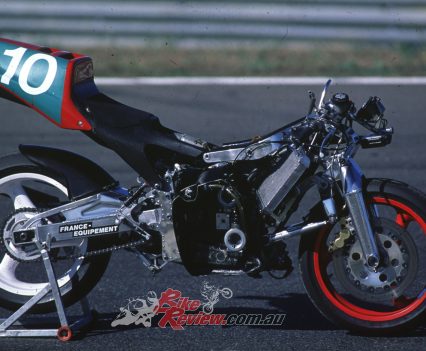

For 1983 Fior produced an even more innovative design, built around a Kobas-style twin-spar aluminium frame fitted with his trademark wishbone front suspension, but the rotary-valve Suzuki motor had reached the end of its competitive life, so for ’84 the first three-cylinder Fior-Honda RS500 was built. This was initially raced with success by Philippe Robinet and Thierry Rapicault, but in due course would turn Pif’s close Swiss friend Marco Gentile, 1985 European 500cc champion riding a Yamaha, into the top 500GP privateer of the 1980s, gaining the Fior marque’s first 500GP championship points in a series packed with works bikes, with points only awarded down to tenth place.

A pair of 250GP contenders were also built, first another Yamaha raced by Marc Gual in 1984 GPs, then in 1987 a Rotax-engined bike for Christian Boudinot that carried the idea of a twin-spar frame to its ultimate logical conclusion. For the Fior-Rotax chassis consisted of little more than two aluminium plates sandwiching the long tandem-twin engine, and the result had to be ballasted to meet the then-250 class weight limit of 90kg, as well as proving very quick-steering.

“For the Fior-Rotax chassis consisted of little more than two aluminium plates sandwiching the long tandem-twin engine, and the result had to be ballasted to meet the then-250 class weight limit of 90kg.”

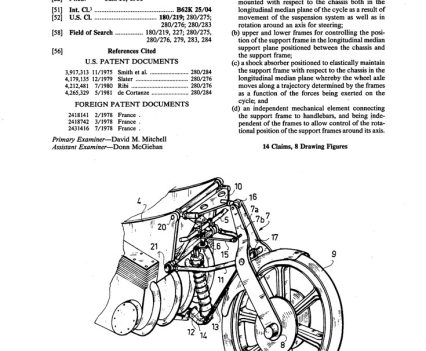

The Fior wishbone fork was copied by the Hossack front-end later developed in Britain, followed a decade later by John Britten in NZ (who was an active disciple of Fior’s) but in a different material: carbon-fibre rather than aluminium. But the greatest recognition of its worth came in 2008, when BMW adopted it on its new four-cylinder K-series models. In doing so, the German company gave credit (but no royalty!) for the Duolever wishbone front suspension to British-based Zimbabwean engineer Norman Hossack, who’d raced a Yamaha TZ350 in the UK while working as a race mechanic at the McLaren Formula 1 team.

That’s where in 1979 he first had the idea of adapting a racing car’s wishbone front suspension to motorcycle use, by effectively rotating it through 90 degrees. Although Hossack succeeded in patenting the design in 1984 (but later allowed this to expire, allowing BMW to adopt it on the first K 1200 S unencumbered by licence or royalty agreements), in fact this ought never to have been granted to him.

“Even before Hossack had built his first bike with a wishbone fork, Fior had scored FIM World Endurance Cup points with his design.”

For, just as with Honda’s Pro-Arm adoption of ELF’s single-sided rear swingarm, which Moto Guzzi had in fact manufactured in volume on the Galletto model 20 years before the French company succeeded in patenting a similar format, Claude Fior had indeed independently developed an identical wishbone front suspension design to Hossack’s much earlier, but had never bothered to patent it. Indeed, even before Hossack had built his first bike with a wishbone fork, Fior had scored FIM World Endurance Cup points with his design.

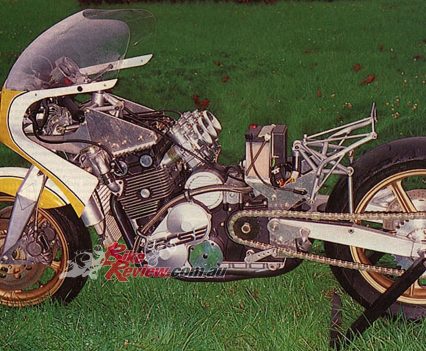

La fourche Fior has several benefits, including the separation of steering and suspension functions, so that the front suspension doesn’t freeze when you trailbrake into a turn; superior suspension compliance, thanks to a fully-adjustable single shock mounted behind the steering head (usually on all Fiors a sophisticated and very light locally-made Fournalès air shock); and zero deflection under braking, so constant steering geometry.

The wishbone fork, with the front wheel gripped between a fabricated aluminium upright mounted on twin articulated parallelogram links, also offers immediate and subtle adjustment of all chassis geometry – trail, head angle, wheelbase, ride height and weight distribution – as well as easier fine tuning of suspension settings than is possible on even the most sophisticated telescopic fork. Add in the enhanced stiffness to weight ratio, and reduced unsprung weight, of a Fior front-end compared to a telescopic fork, and you can appreciate the reasons for the fanatical belief which Pif possessed in the worth of his design.

“My fork offers greater stiffness of the load-carrying components, as well as greater sensitivity thanks to the absence of stiction, compared to telescopics.” said Claude Fior…

“My fork offers greater stiffness of the load-carrying components,” he testified to me, “as well as greater sensitivity thanks to the absence of stiction, compared to telescopics. My design also has inherent antidive which can be altered at will, and retains a constant wheelbase under braking. The short wheelbase and high centre of gravity of most of my designs, plus a steep head angle and reduced trail, all allow the rider to maximise the capabilities of the front tyre, in keeping up corner speed while steering securely. The most critical aspect of a bike’s handling is to enter a corner as fast as possible, and maintain turn speed in it, even over bumps.”

“The only negative factor which prevented this being maximised with my design was the refusal of the tyre companies to make front tyres with a stiffer construction specifically to suit the needs of a non-tele forked bike like mine. ELF and Bimota had the same problem – and even they couldn’t find a way round this, so a small constructor like me had no chance.”

Still, Fior went one better than ELF and actually realised his dream of constructing the only 100 per cent French-built four-cylinder 500GP racer of the modern era, powered by his own engine, which was derived from the JPX sidecar motor built by the same company in Le Mans which later manufactured the engines for George Beale’s six-cylinder 250 Honda replicas.

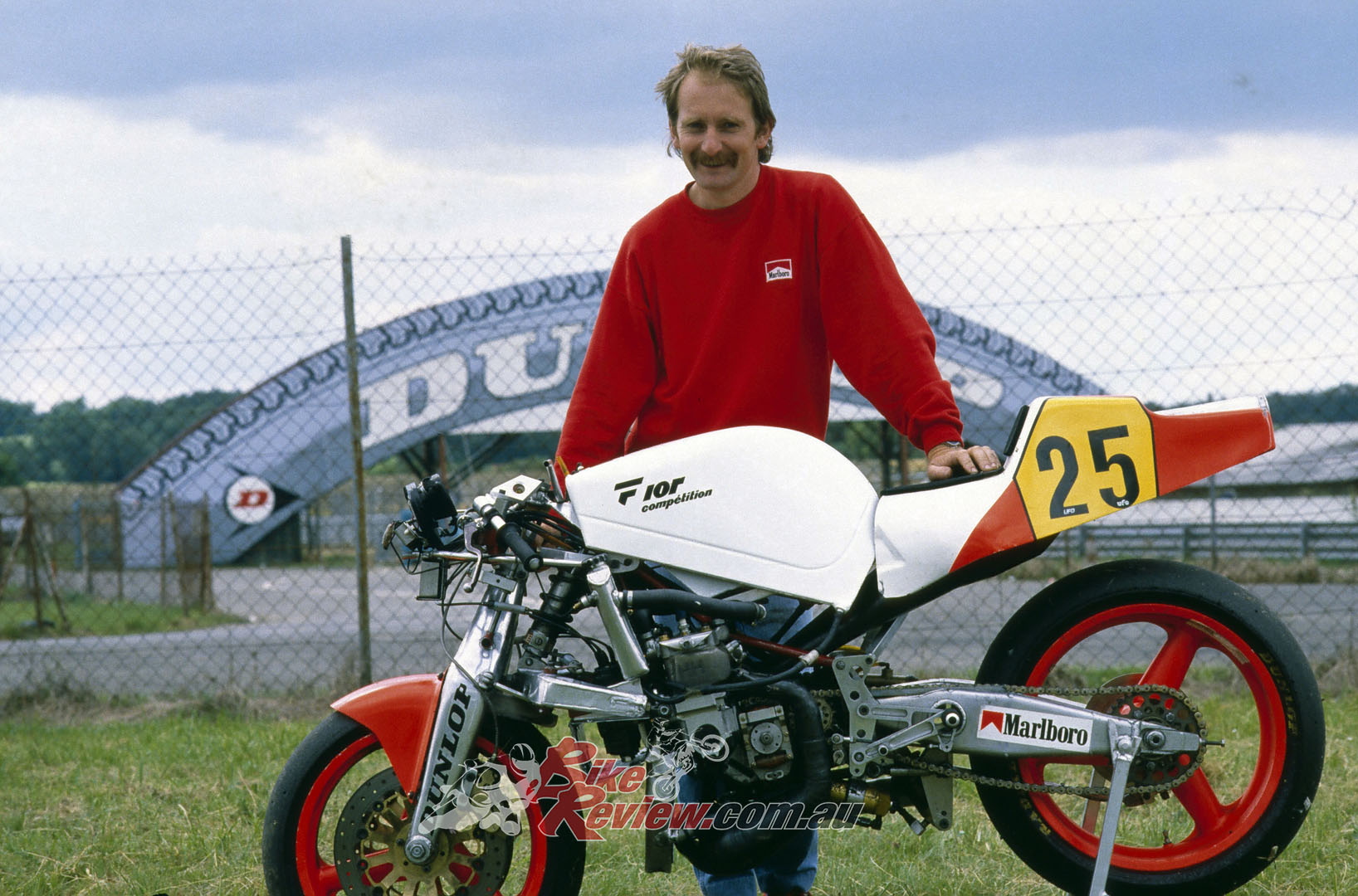

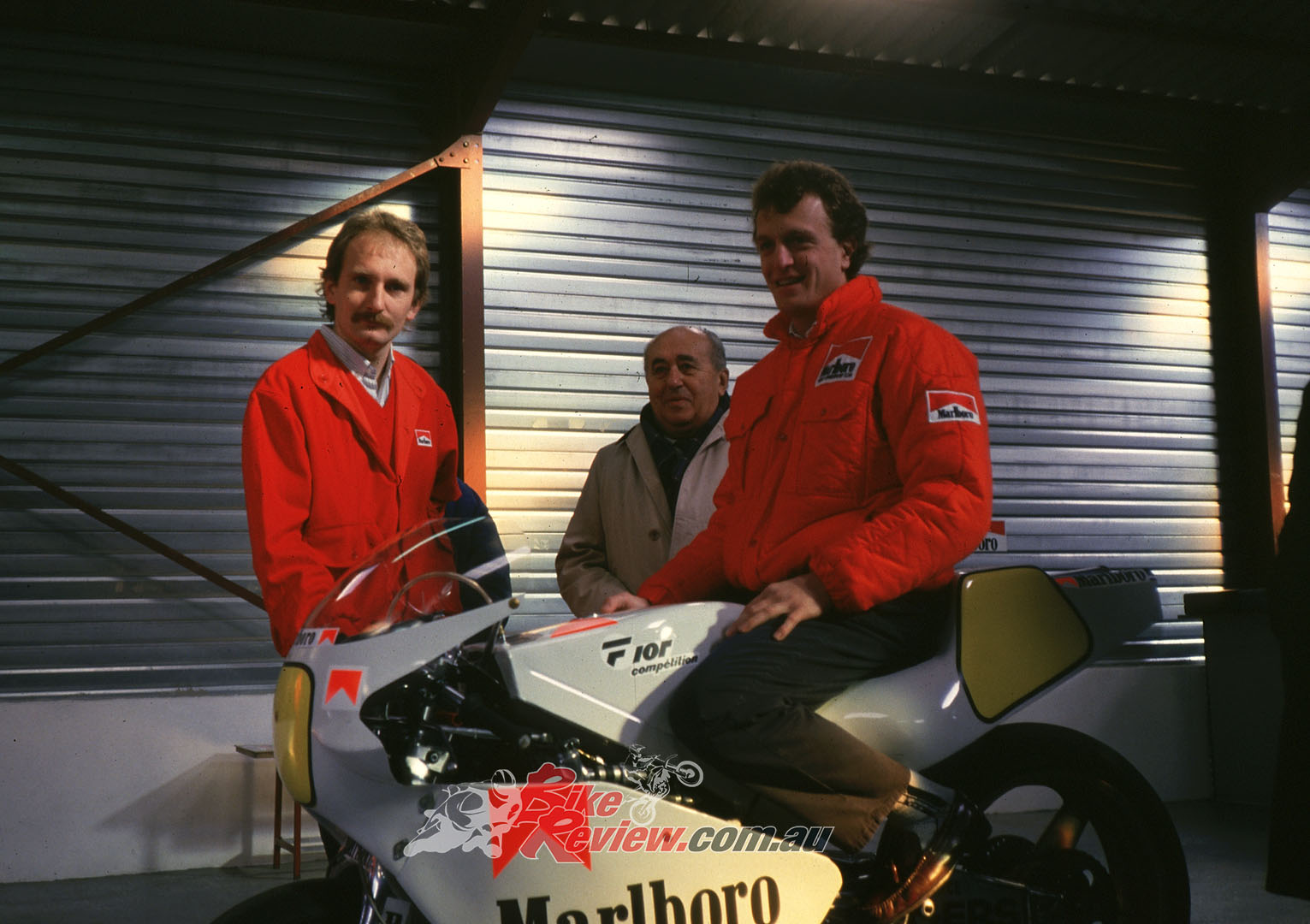

The crankcase reed-valve in-line four debuted in 1988, and raced for two seasons with increasing success in Marco Gentile’s hands, thanks to Marlboro backing.

The crankcase reed-valve in-line four debuted in 1988, and raced for two seasons with increasing success in Marco Gentile’s hands, thanks to Marlboro backing – to the point that, in 1989, Gentile actually finished the season level on points with Randy Mamola on the works Cagiva: Fior had deadheated with the billion-lire Italian team for the honour of being top Euro-bike in the 500GP World Championship, on a fraction of Cagiva’s budget, despite missing the final three races of the season owing to injuries sustained in a road accident. But the end of Marlboro’s support, and Gentile’s tragic death at Nogaro that winter driving a Fior-built TZ350-powered go-kart – an event which troubled Pif deeply for several years – meant a step down to the 250cc class in 1990, but with an exciting objective.

The Aprilia factory had bought an option on Fior’s suspension patents, for possible use on their streetbike range, and gave Pif the budget to build a bike for Frenchman Alain Bronec to race in 250GPs that season, to prove its worth against the equally radical but quite different rival OZ design from Italy. Sadly, Pif remained convinced to the end of his days that Italian politics played a part in preventing a fair comparison between the two ever being made: Aprilia would only supply the Fior team with customer V-twin rotary-valve engines, whereas their Venetian neighbours OZ used works motors that were quite a bit more powerful – yet still often finished behind the French bike.

“Aprilia would only supply the Fior team with customer V-twin rotary-valve engines, whereas their Venetian neighbours OZ used works motors that were quite a bit more powerful…”

At the end of the season Aprilia dropped the Fior project – but by no coincidence the completely new OZ-Aprilia which appeared for the ’91 season featured a copy of the Fior front suspension design! But you could never buy an Aprilia roadbike with a Fior fork…..

Not that it wasn’t possible to buy a Fior-built streetbike for more than a decade – only, not with his name on it, and not with his trademark front suspension layout. One exception that you couldn’t buy was the most radical of the more than one hundred bikes Pif built for his friend Thierry Henriette, today the manufacturer of Brough Superior and Aston Martin motorcycles all equipped with la fourche Fior, but back then boss of the Boxer Bikes dealership in Toulouse, and guru of the French stylebike sector.

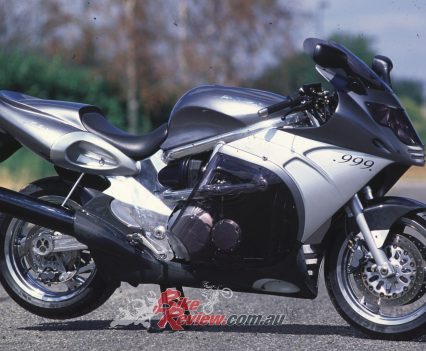

This was the Kawasaki GPZ1100RX-powered BA737 ‘Banana Fritter’, which Pif designed and built for Henriette as a show model in 1989, complete with wishbone fork – and exhausts exiting through the swingarm! Insane!

This was the Kawasaki GPZ1100RX-powered BA737 ‘Banana Fritter’, which Pif designed and built for Henriette as a show model in 1989.

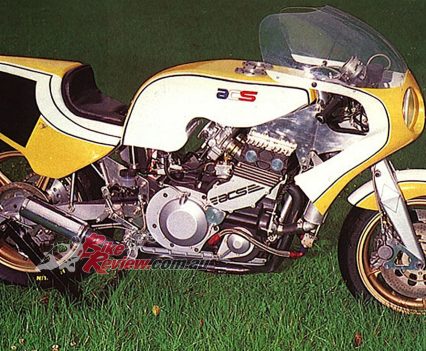

Back in 1981, though, it had seemed as if the first French Superbike of the modern era would introduce the Fior chassis concept to the street, because the lovely, innovative three-cylinder 12-valve fuel-injected ACS-Siccardi 1000 S3 prototype did indeed have a Fior frame and front suspension – only this promising project was aborted thanks to some more politics, this time a la française.

For that year there was a change of government in France, and the state support that had been promised to underwrite production of the Siccardi was withdrawn in favour of the rival BFG-Odysée project’s Citroën car-engined monstrosity. Why? Because the BFG directors were cronies of the newly-elected Mitterand Socialist government, while Monsieur Siccardi was in a rival party!

So, no Fior with a licence plate – but instead Pif designed and manufactured a series of more conventional but still exquisite aluminium frames for Boxer’s limited edition customer bikes, including 60 Kawasaki-powered Vecteurs from 1983 onwards, 30 Honda VF1000-engined Sensors debuting in 1985, and a total of 40 Lamborghini motorcycles from 1986-88, with Kawasaki GPz900 motors. Fior also built a host of specials bearing the Boxer name, most notably the four-cylinder Triumph 1000 Daytona-based Gladiateur, and the Aprilia Pegaso-engined Scrambler single, which in turn gave rise to the later series-production Voxan V-twin Scrambler designed by Thierry Henriette.

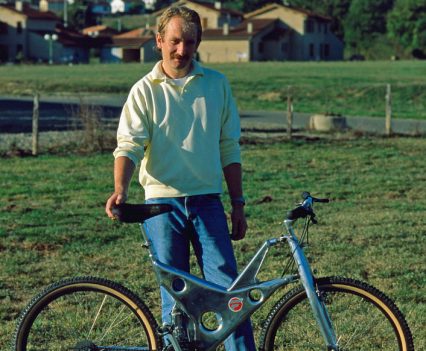

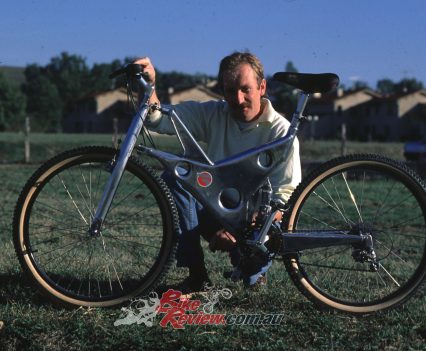

But the Fior flair didn’t extend only to making motorcycles – for Pif was a true Renaissance man, ready to turn his gift for original thought to a host of challenges. Like the self-designed all-aluminium mountain bike he concocted in 1990, complete with Fournalès air shock and Fior fork at a time when suspension was far from commonplace on off-road bicycles: he built 50 replicas for sale to discerning dirt devils.

Any chance to browse the storerooms of the Fior Concept factory at Nogaro always unearthed some surprising finds – each the product of Pif’s fertile mind. Like the Rotax-powered dune buggy he constructed to race himself at his local autocross track, or another of his 68bhp TZ350 Yamaha-engined Superkarts, with motorcycle twistgrip throttle and handlebar steering. Squeezed in a corner you might find the prototype ciclomoteur racer with single-speed engine and friction drive to the front wheel which Pif built for the giant Peugeot factory using his own alloy chassis, spawning the dozens of replicas which became the must-have hot tip in the looney world of French moped racing.

“Any chance to browse the storerooms of the Fior Concept factory at Nogaro always unearthed some surprising finds – each the product of Pif’s fertile mind.”

Then, up on a shelf might be the motorised skateboard which was the terror of the Grand Prix paddocks in 1989, before the po-faced IRTA bosses banned its use as being ‘detrimental to the image of Grand Prix racing’! Very PC. Same went for the motorised rollerskate Pif used to scoot – literally! – down to race control on – but Fior got his own back, though: he’d get Marco Gentile to tow him round the paddock behind a scooter, on what looked like just his trainers but was in fact a new pair of brake pads being ‘run in’ beneath their soles. Pif wanted to organise a Mechanics vs. Riders match race for this arcane sport in the Donington Park paddock, but IRTA wouldn’t hear of it. Too much like fun for its pseudo-Ecclestone hierarchy, even in those pre-Dorna days….

Claude made himself a bit of a menace in the pits. Seen here getting pulled along with brake pads under his shoes.

Fior’s engineering talents extended to more serious subjects, though – including three different types of aeronautic creation: one was his self-made aluminium-skinned glider, which he’d take up himself to trip with thermals on a clear Gascon summer’s day above Nogaro, towed into action by a Midour – Fior’s own design of glider tow-plane which he’d named after a local bottled water. Or there was the lightweight airplane powered by a turbocharged Norton rotary engine, which he built himself to attack the world altitude record for aircraft weighing less than 1000kg.

Read our Throwback Thursday on the ELF 500 GP Racer here…

But having given up his quixotic struggle to establish the worth of his avantgarde chassis design on two wheels in the wake of Gentile’s death, Fior went on to achieve the commercial success on four wheels that always eluded him on two. And, ironically, he secured it through an active alliance with ELF, the company whose equally innovative bikes powered by works Honda engines achieved the acclaim that Pif’s own chronically underfunded GP efforts never obtained, despite being equally successful. Working in conjunction with the French petroleum giant’s promotional division, and Renault Sport, Fior developed a low-budget single-seater racing car powered by a tuned 1400cc Renault Clio engine for an inexpensive beginner’s category called Formula Campus.

Fior Concept built several hundred such cars for use in Asian countries such as Taiwan, Thailand and China, where the class became the chosen formula for aspiring young drivers to start in. His collaboration with Renault extended to prototype work, such as building the original version of the avatgarde Renault Spider sports car which later reached production. This and his work in developing electric vehicles kept the staff of 30 employees at Fior Concept’s Nogaro factory very busy – until the tragic accident in 2001, which represented such a loss for both the car and motorcycle worlds.

Claude Fior was that rare thing – a man bursting with complex and innovative technical ideas who was also a warm, convivial human being with a multitude of interests, who didn’t take life too seriously, but who made the most of every moment. His passing was a great loss to all those who knew him, and 20 years on since the motorcycle musketeer departed the scene, he’ll still never be forgotten.