It’s one of Grand Prix racing’s best-kept secrets, in 1975 Harley-Davidson went racing in the 500GP class against Japan’s finest, and beat them to win races... Photos: Stefano Gadda

The chance to ride the one and only factory Harley-Davidson 500GP racer ever built came on a summer’s day at Pirelli’s Vizzola test track, in the shadow of Milan’s Malpensa airport and just half an hour from the lakeside Schiranna factory near Varese where it was built.

Built during the winter of 1974-75, it’s lived all its life near there, too – for after making trips to Austria and then the USA for Harley’s top gun of the day, Gary Scott, to race it there, the liquid-cooled four-carb twin-cylinder reed-valve two-stroke returned each time to its Varese base. Then, during the winter of 1995-96, one of the men who was responsible for conceiving it and looking after it throughout its racing career, Albino Fabris, acquired it together with a still unsold customer bike, and nowadays prepares them both for his son Giorgio to ride in Italian historic events.

Read Alan Cathcart’s previous Throwback Thursday and other tests here…

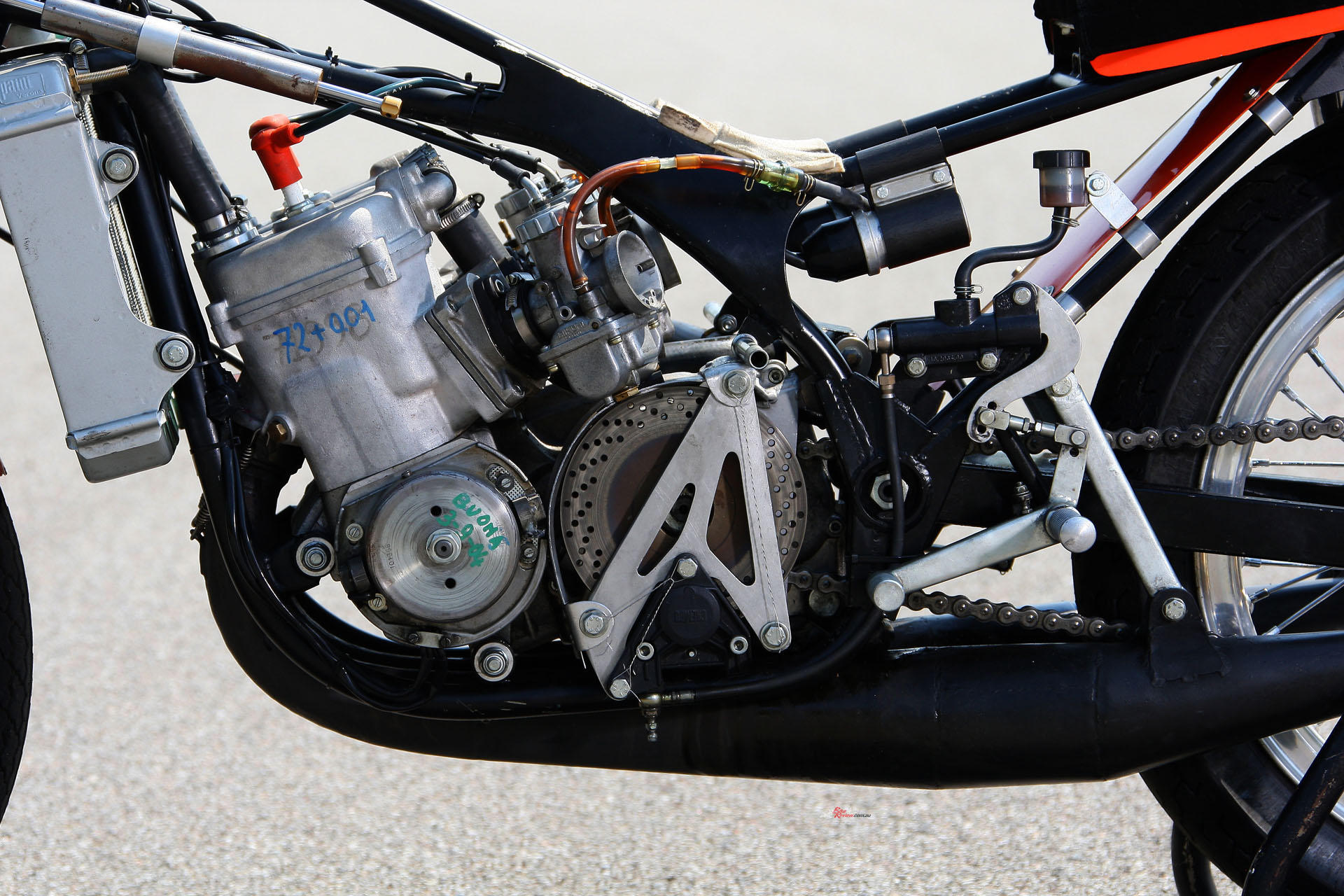

With its Mikuni carbs, Girling shocks and lightweight construction the bike awaiting me in the summer sunshine was the factory racer that was essentially a one-year wonder raced for a single season in 1975. Having ridden several of its contemporary rivals I was able to compare and contrast the Italian-built American GP racer with its competition.

“Having ridden several of its contemporary rivals I was able to compare and contrast the Italian-built American GP racer with its competition”…

Most particularly Suzuki’s twin-cylinder piston-port TR500 XR05 that preceded the RR500’s creation, as well as Barry Sheene’s 1975 Dutch TT-winning RG500 Suzuki XR14 rotary-valve square-four whose debut in customer guise for the 1976 season effectively killed off the Harley twin’s reason to exist.

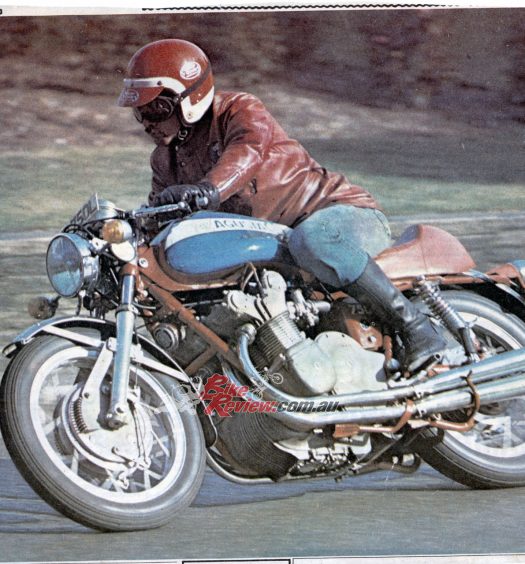

With its portly build occasioned by the massive 30-litre fuel tank required to allow the thirsty four-carb twin to do a full 250km GP race non-stop – the Kawasaki H1R triple that was its most competitive privateer two-stroke rival needed a secondary fuel tank in the seat tail to go such distances without refuelling – it was a surprise to find the Harley’s riding position so close-coupled and compact, with its short 1410mm wheelbase resulting in a nimble and quick-steering package that felt closely derived from the ex-Pasolini 250 twin I was riding the same day, also owned by Albino Fabris.

The 30L fuel tank allowed the RR500 to finish a 250km race. That’s not bad fuel economy for a 500GP bike!

This made moving around on the 500 twin pretty difficult, but being wedged more or less in place was par for the course back then in those pre-kneeslider days, and the four carbs with the outer pair sticking out at an angle don’t leave your legs too widely splayed to avoid them, though I must admit to be aware of them at all times.

“It was a surprise to find the Harley’s riding position so close-coupled and compact, with its short 1410mm wheelbase resulting in a nimble and quick-steering package”…

The RR500 feels very much like a jumbo sized version of its 250 kid sister, which I suppose is what it is. I bet the first few laps of any GP race must have required some care, with such a heavy fuel load that would have made the bike feel distinctly top-heavy. The reduced fuel load needed for shorter Italian National series rounds would have been much less challenging.

“From 7000rpm upwards there’s a big hit of extra acceleration as the Harley really gets on the pipe”…

However, in keeping with its build is the grunty, torquey nature of the motor, and despite any concerns I had at the outset that fitting two 34mm carbs to each 244cc cylinder might have resulted in over-carburating it, the reed valve format results in a very usable, practically syrupy power delivery from quite low down. It pulls from 4,000 rpm upwards with a relatively smooth transition into the powerband delivered with the aid of the carefully concocted stinger exhausts – engine tuner Ezio Mascheroni was a wizard of expansion chamber design.

But from 7000rpm upwards there’s a big hit of extra acceleration as the Harley really gets on the pipe, resulting in a powerwheelie when you cross that threshold in any of the bottom three ratios of the sweet-shifting six-speed gearbox with right foot, one-up race pattern action. The clutch is super light, making it easy to finger the lever to coax the motor into the powerband exiting a slow bottom-gear turn like the tight hairpin on Pirelli’s test track.

It may have carried an American badge on the fuel tank, but this was essentially Italy’s first 500GP two-stroke contender…

The reed-valve engine with 180º crank doesn’t vibrate unduly, and will run to 12,000rpm as shown on the distinctive and very readable black-faced Veglia tacho before falling off the pipe, but that results in a mile-wide spread of power by two-stroke standards that makes this such a usable, rider-friendly package. That’s not a term you’d normally use for 1970s two-stroke GP racers, but well merited here because of the reed-valve format.

“Where the Harley stands out versus its Japanese competition is in the way it steers, and above all stops”…

No wonder Michel Rougerie won first time out on the bike’s debut at Rouen in the pouring rain – it must have been a good bike to ride in slippery conditions, with such a smooth and torquey power delivery, and a broader spread of power than the more peaky Japanese twins, triples and fours it competed against.

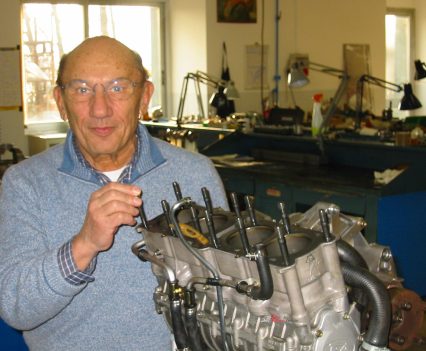

Albino Fabris, owner, watching Alan test his priceless RR500. Albino is one of the four men together with Ezio Mascheroni, Claudio Lazzati and ex-racer Gilberto Milani who made up the Harley GP team’s engineering crew.

It may have carried an American badge on the fuel tank, but this was essentially Italy’s first 500GP two-stroke contender, so it led directly to the four-cylinder Cagivas that were developed in the very same workshop, starting just half a decade later.

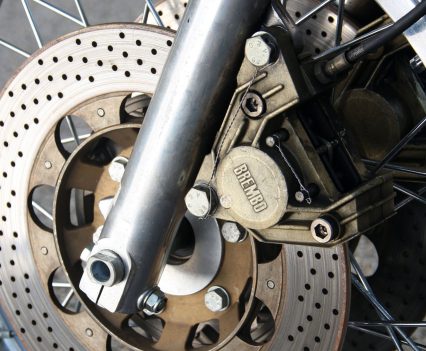

Another area where the Harley stands out versus its Japanese competition is in the way it steers, and above all stops. Despite the short wheelbase it’s super stable braking hard at the end of a straight as you prepare to tip it into a tight turn, and the Brembo cast iron discs really have lots of bite, especially by the standards of the era when the stainless steel discs on the Sheene Suzuki, for example, were dangerously ineffective by comparison.

Weighing just 124kg, and with 89bhp at the wheel, the RR500 was extremely quick with a top speed of 280km/h

Plus there’s quite a bit of engine braking from those two big pistons, though you must be careful not to overbrake with your left foot, as it’s all too easy to lock the back wheel via the disc mounted on the transmission shaft. I survived a couple of lurid slides until I learnt to be more sensitive. But one reason for the comparatively sweet handling of the tubby-looking twin is surely the way the mass has been compacted by mounting the rear brake amidships in the wheelbase.

I also didn’t suffer from any rear end chatter – once I’d learned the right amount of foot pressure to use – even using quite significant overrun in shifting down three or four gears for a slow bend, and taking advantage of that surprising amount of engine braking for a stroker.

Alan powering off a corner on Pirelli’s Vizola Ticino test track, in Milan on the twin-cylinder 500cc two-stroke.

Really, though, you do have to say this bike represents a missed opportunity for Harley-Davidson – both as a racer and as a road bike. If its Italian technicians had concocted it even two or three years earlier, it could have been an ultra-competitive privateer racer, and for sure all 25 bikes envisaged would have found a home, and earnt their owners a good living.

It wouldn’t have taken a motorboat-engined special – which is what Kim Newcombe’s König essentially was – to break down the doors of convention and provide a competitive privateer mount at the dawn of the two-stroke era, because Harley would have been there first with a properly developed, good-handling twin. But the timing was off, for by 1976 the days of such a bike being competitive were over, with the arrival of the four-cylinder RG500 which literally took over 500GP racing grids. Pity….

Harley-Davidson RR500 Specifications

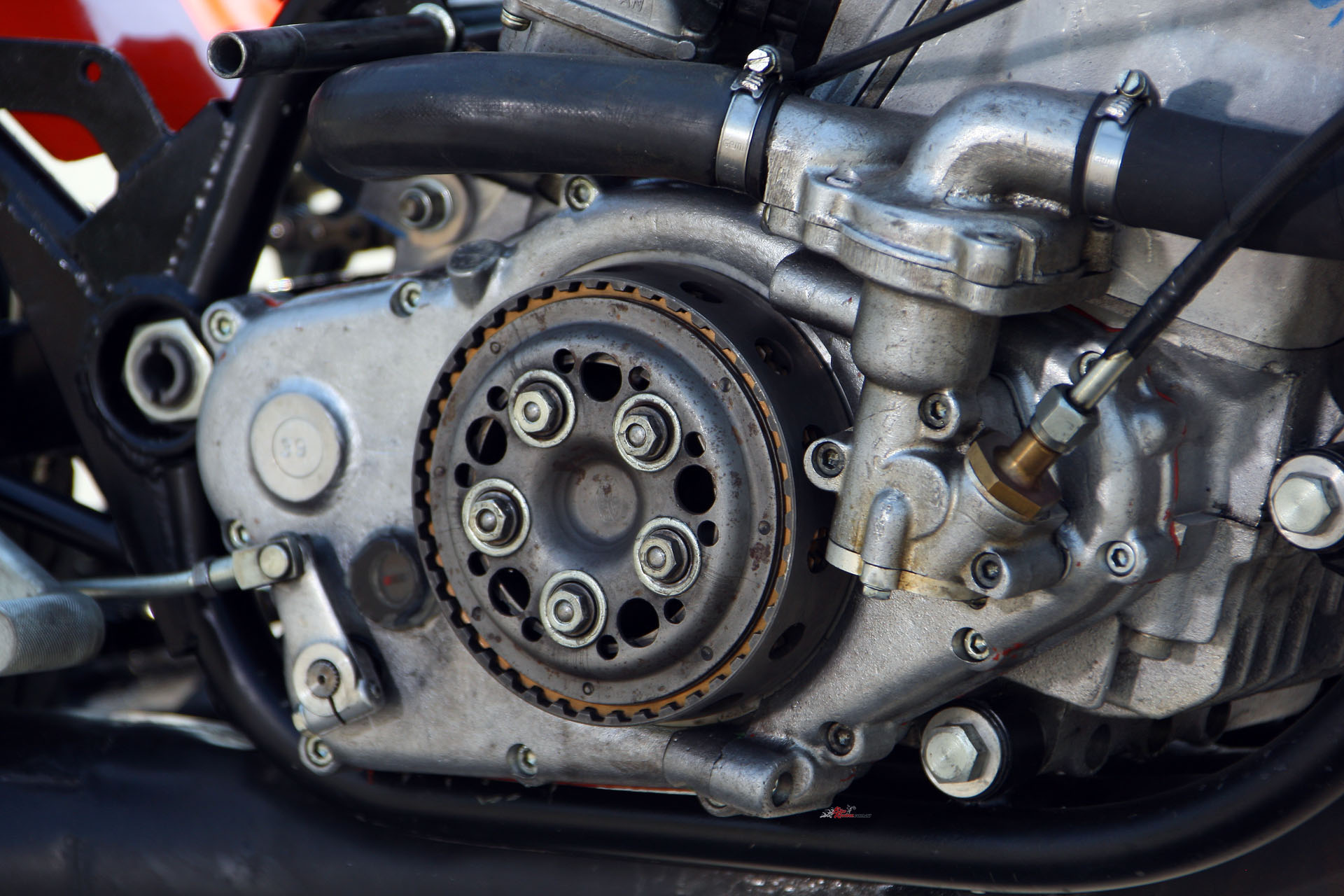

Engine: Water-cooled reed-valve parallel-twin two-stroke with 180-degree crankshaft, 72mm x 60mm bore x stroke, 488cc, 12:1 compression, Dansi self-generating CDI ignition, six-speed extractable gearbox, Surflex 16-plate dry clutch with bronze plates, 4 x 34mm Mikuni round slides (as tested) with two reed-valve packs per cylinder, Ezio Mascheroni designed expansion chambers.

Chassis: Chrome-moly tubular steel duplex cradle frame, tubular steel swingarm, twin Girling shocks, 35mm Ceriani forks, 26º rake, 85mm trail, 1410mm wheelbase, 53/47% weight distribution (customer bike 51/49%), 2 x 280mm cast iron Brembo rotors, twin-piston Brembo calipers, 170mm Brembo cast iron rotor, single-piston Brembo caliper, WM2/1.85 and WM2/2.15in Borrani alloy spoked wheels, 3.50 – 18 and 3.75 – 18 Dunlop KR124 tyres.

Performance: 89bhp@10,500rpm and 68Nm@6800rpm at wheel, 124kg with oil/water no fuel, 280km/h top speed. Owner: Albino Fabris, Varese, Italy.

Harley-Davidson RR500 History and Tech

As a home run two-wheeled Trivial Pursuits question, it has few equals. Exactly fifty years ago in 1975, Harley-Davidson competed in road racing’s 500cc World Championship against the Suzuki and Yamaha factories and their customers with a two-stroke Grand Prix racer – true or false? Sorry to disillusion any Hog experts, but however unlikely, this happens to be TRUE!

OK, not exactly a full season of GP competition, more just a handful of races on the World stage, including one for Harley-Davidson’s factory rider Gary Scott, who retired his H-D RR500 from the Austrian GP held at the Salzburgring in early May that year with engine problems. But by then the same such bike had already finished seventh in the season-opening French GP at Paul Ricard in the hands of Michel Rougerie, in a race won by Giacomo Agostini making his two-stroke GP debut on a Yamaha after his shock switch from MV Agusta.

Rougerie also scored two non-title international victories in France on the Harley RR500, and his 250/350 GP factory team-mate and the Motor Company’s reigning 250cc World champion, Walter Villa, had given Phil Read’s four-cylinder MV Agusta a serious wakeup call in early Italian championship rounds with the same bike. Yet later that same year the twin-cylinder four-carb Harley-Davidson RR500 project died away almost as mysteriously as it had been born, leaving Harley’s Italian factory where the bike had been created to focus on retaining its 250cc World crown with Villa that year, going on to make it a hat-trick of titles in 1976, as well as doubling up by winning the 350cc World championship that year, too.

Those achievements were the work of the close-knit band of just four men who comprised the Harley-Davidson road racing team working out of its Italian subsidiary’s lakeside factory at Varese that formerly housed the Aer Macchi flying boats. These competed against the Supermarine Swift, Britain’s forerunner of the legendary Spitfire, in the 1930s Schneider Trophy seaplane races that captured the imagination of audiences around the world via newsreel coverage of the events.

Postwar, Aermacchi (sic) became a motorcycle manufacturer to compete with dozens of other companies in catering for the need for personal transportation in war-ravaged Italy – so successfully that in 1960, Harley-Davidson purchased 50% of the company as a source for lightweight motorcycles to be sold in America alongside its Milwaukee-made V-twins, acquiring the remaining 50% in 1974. But just four years later in 1978 it sold its Italian subsidiary to the Castiglioni brothers, who renamed it Cagiva – only in due course, in 1998, to re-baptise it as MV Agusta, which it remains today, now under KTM ownership.

Throughout the 1960s Aermacchi H-D had gone road racing successfully with its air-cooled horizontal-cylinder OHV singles, sold in the USA as a Harley-Davidson Sprint. But in 1971 the Varese-based factory began developing a two-stroke 250cc twin, after its prodigal son Renzo Pasolini had rejoined Aermacchi from Benelli to race it. In 1972 Paso lost the World Championship by a single point to Yamaha-mounted Jarno Saarinen – only for fate to decree that they should both lose their lives in the terrible crash in the 250cc Italian GP at Monza the following May. Paso’s vacant seat in the squad – by now rebaptised as a full Harley-Davidson team – was taken by the up and coming Gianfranco Bonera, and as Albino Fabris, one of the four men together with Ezio Mascheroni, Claudio Lazzati and ex-racer Gilberto Milani who made up the Harley GP team’s engineering crew recalls, it was thanks to him that the RR500 project came about.

Alan and Albino Fabris warming up the RR500 at the Pirelli test track. Who wouldn’t love a spin on that!

“We’d made a 350cc version of the 250 twin, which by now was liquid-cooled,” Fabris says. “We also built a 385cc version of that, and in the final round of the 1973 Italian 500cc championship at Misano, Bonera gave Phil Read on the four-cylinder MV Agusta a lot of trouble throughout the race, and only narrowly finished second to him, ahead of all the other true 500s, after setting the fastest lap. Well, that set us all thinking about what might be possible with a purpose-built full 500, and since Walter Villa who had by then also started to ride for us didn’t like the 385, and wanted to race a full 500cc bike, we decided to ask our management to let us build one.”

The answer from Harley’s Italian subsidiary’s management was a positive one – but with certain conditions. Though its Italian spinoff was doing OK, the US parent company by then controlled by AMF was suffering a slide in sales caused by both quality issues and increased Japanese competition, so there was a strictly limited budget to develop the bike, and it would have to be offset by making a customer version available. Oh, and a minimum of 25 examples of this had to be built in order to homologate it for AMA competition. Otherwise, go ahead, guys – see what you can do!

As always in Italy, passion overcame whatever restrictions might have been thought to be imposed, and during the spring of 1974 engine designer Egisto Cataldi – already the creator of the 250/350cc parallel-twins that would shortly gather up a total of four World titles – worked after hours at home to design the RR500 engine from a clean sheet, with only the gearbox casing and some minor details carried over from the smaller engines.

Like these, the new Harley RR500 was also a watercooled parallel-twin with a 180º crank, and its six transfer/dual intake/single exhaust port cylinders that were canted forward 15º from vertical measured 72 x 60 mm for a capacity of 488cc. But unlike its piston-port predecessors, the new Biancone (as in Big White, referring to the fact that the factory bike raced in a plain white fairing for a couple of its early races!) had a reed-valve engine, in an attempt to soften the power delivery and make the bike more tractable on tighter tracks.

However, the problem was that there wasn’t yet a reed valve pack big enough for the bike’s requirements – nobody made them at all in Italy, so they couldn’t even persuade someone local to make them a special design. The only solution was to use a pair of Yamaha reed valves on each cylinder sourced from the newly launched four-cylinder TZ750, so that meant doubling up on carburettors, too, with two 34mm Dell’Ortos mounted to each cylinder, with the reed blocks splayed apart at an angle for clearance.

These were later replaced on the single factory racebike by 34mm Mikunis, while the total of 18 RR500 engines built (not 25, whatever they told the AMA!) resulted in 16 complete motorcycles being sold to customers that winter for Lire 3,500,000 each (just on US$ 5,000), all of which retained the Dell’Ortos. 5% petroil mixture was used, perhaps surprisingly employing Shell’s outboard engine lubricant for boats. They must have had some left over from the Schneider Trophy support vehicles!

Ignition was provided by a self-generating Dansi CDI mounted on the left end of the crank with just 21º of advance, and the 89 bhp delivered to the rear wheel at 10,000 rpm (with maximum torque of 68 Nm/ 6.9 kgm/50 ft-lb at just 6,800 rpm – quite a two-stroke tractor!) was transmitted via an extractable cassette-type six-speed gearbox with different standard ratios than the 250/350, matched to a 16-plate Surflex dry clutch positioned on the left behind the generator.

This muscular-looking motor was mounted in a chrome-moly tubular steel duplex frame very similar to that of the smaller bikes, but subtly reinforced, with a 55mm longer swingarm delivering a 1410mm wheelbase. This contained the eccentric chain adjuster in the axle mount, as opposed to in the swingarm pivot on the smaller engined bikes. The RR500’s 35mm Ceriani fork was set at a rangy 28º rake with just 85mm of trail, but after starting out with twin Ceriani shocks at the rear, the team soon adopted Girlings. Up front on all the customer bikes a pair of 280mm Brembo cast iron ventilated discs was gripped by twin-piston Brembo Serie d’Oro gold calipers, with a 200mm Ceriani single leading-shoe drum brake at the rear, and Borrani 18-inch alloy rims at both ends – a WM2 front and WM3 rear.

On the works racer, however, the team initially experimented up front with the unique and much more costly 260mm Campagnolo so-called ‘hydro-conical’ cast alloy wheel, with a hydraulically-operated conical drum brake contained inside the hub, and as Walter Villa was a fan of this (he used it extensively on his 250 World champion bikes) they experimented with it for some time before reverting to more conventional twin discs for 1976, after Villa stopped riding the RR500.

However, the rear disc brake setup on the factory bike was a different matter, and was retained throughout its career, having been invented by the team and patented by Harley. “We wanted to prevent rear wheel hop under hard braking, which was inevitable with the inertia forces caused by such big cylinders, and gave the chain a hard time,” says Fabris. “The rear brake assembly weighed four kilos, so moving it to the centre of the bike and attaching it to the gearbox output shaft not only reduced unsprung weight and thus improved suspension compliance, it also compacted the mass more centrally, and made the bike steer better.” The 170mm cast iron disc was gripped by a single-piston caliper, and cooled via a duct in the side of the fairing. With this installed, the factory racer scaled 124kg with oil/water but no fuel, split 53/47% forwards, as against the 130kg weight of the customer bikes, split 51/49%. Wonder why Harley hasn’t made more use of this patent since then – for example, on its VR1000 Superbike? Or did it maybe forget it ever had it….?

After developing the RR500 in track testing during the second half of 1974 – in between defeating Yamaha to win Harley-Davidson’s first-ever genuine World championship of any kind in the 250GP class – the RR500 model’s racing debut actually came about on March 16, 1975 in two different countries. First, Michel Rougerie took one of the customer bikes delivered to its French importer to victory first time out on the public roads Rouen circuit, in an international 1000cc race run in wet conditions ahead of a fleet of TZ750 Yamaha riders including Chas Mortimer, Jon Ekerold and Kork Ballington, as well as the TZ350-mounted Patrick Pons.

That promising start was backed up by the factory bike’s debut the same day in the first round of the Italian 500cc championship at Misano, in which Walter Villa on the new Harley twin led Phil Read’s MV Agusta four for most of the race, until he was forced to retire when it got stuck in gear thanks to a broken selector spring. Three days later he finished third behind the victorious Read in the second round of the series at Modena, and four days after that Rougerie won again on his customer RR500, this time in the dry at Magny-Cours where he took victory in one leg of the Trophée des Millions Open Class international, winding up second overall behind Christian Leon’s 680cc König flat-four. Then, the following weekend the Harley RR500 made its (and the American brand’s) 500cc Grand Prix debut, with Rougerie finishing seventh in the French GP at Paul Ricard. In April, Villa managed fourth on the works bike in the third round of the Italian 500 series, again at Misano, but retired from the race at Imola two weeks later with a seized engine.

Grand Prix duties then intervened, and while Villa focused successfully on retaining his 250GP World title, the baton was passed to Harley’s No.1 American factory rider Gary Scott, who after testing the bike earlier in the year at Monza and coming away satisfied with it, made his Grand Prix debut on the RR500 in May’s Austrian GP at the Salzburgring, retiring from the race however with unspecified engine problems. Any plans Scott might have had to race the bike further in 500GP events were aborted when he found himself in a tight battle for the AMA championship with his Yamaha-mounted arch-rival Kenny Roberts, and a new rookie sensation named Jay Springsteen – but Gary did ride it one more time at Laguna Seca in July, in an effort to prevent Roberts gaining too many more points on him. Sadly, though, problems with the RR500’s gearbox meant that Scott DNF’d, and after that racing in Europe at GP level came a poor second for him and above all Harley-Davidson to doing it on the dirt and winning the AMA title, as Gary did indeed achieve that season.

This left the factory RR500 pretty much unwanted though not necessarily unloved, and it was only raced again once more that year when guest rider Mimmo Cazzaniga finished a lowly ninth on it in the Pesaro public roads race in August. But with the essential shutdown of the MV Agusta team for 1976, Gianfranco Bonera returned from there to Harley-Davidson as Walter Villa’s teammate, and to get him dialled in to racing two-strokes again after a two-year absence, Harley shipped the RR500 Down Under for Bonera to race it in the 500cc Australian TT race held in December 1975 at the bumpy Laverton airfield circuit outside Melbourne (the race was supposed to take place at Phillip Island, but a mixture of politics and money forced the move)

The man he’d replaced in the MV Agusta team after he’d switched to Yamaha, Giacomo Agostini, had persuaded Count Agusta to lend him a four-cylinder ‘fire engine’ to contest the race with, only to end up getting beaten on the line by rising young Aussie star Kenny Blake on one of the brand new square-four RG500 customer Suzukis. Bonera finished fifth on the Harley-Davidson twin – but the writing was already on the wall. By introducing a close replica of Barry Sheene’s GP-winning factory rotary-valve four, Suzuki had effectively cut the ground away from any possible market for the Harley twin, making the Italian-made bike yesterday’s papers.

After a single further race early in ’76 back home in Italy at Misano from which he retired, Bonera concentrated on racing the 250/350 Harleys as backup to Walter Villa in Grand Prix racing, finishing third in the 250cc World Championship points table at the end of the season. The works RR500 was not used again, and when he retired from the factory’s Cagiva 500GP team at the end of the 1995 season, Albino Fabris purchased it together with a still unsold customer bike, and nowadays prepares them both for his son Giorgio to ride in Italian historic events.

Michel Rougerie talks to H-D’s Ezio Mascheroni at Paul Ricard in April 1975 before finishing 7th in the French 500cc Grand Prix.

Meanwhile, though, in June 1975 the two spare RR500 engines had been acquired by chassis specialists Bimota, a company which had only been formed in 1973. Until then the only Grand Prix road racer to carry the Bimota name had been a four-stroke Paton 500cc twin, although Walter Villa was about to retain his 250 World title on a chassis designed by Bimota’s technical guru Massimo Tamburini for the Varese-based team. The Harley-Davidson RR500 motor provided them with the chance to step up to a different level than the now outmoded Paton would permit, and the result was a much lower, lighter and generally more purposeful looking twin-cylinder two-stroke than the rather plump-looking factory Harley racer. The Bimota HDB1 with monoshock rear suspension was raced with some success by Vanes Francini, including a rostrum finish in the 1976 Italian 500cc championship round at Mugello, but only a single such bike was ever built.

However, there’s an interesting footnote to the RR500 story – because it was always intended that there should be a street version of the bike! Look closely at the right-side engine cover, and you’ll see a boss behind the clutch for the kickstarter which it was planned to incorporate in such a motorcycle. This was however killed off by the advent in the USA of the first generation Federal anti-pollution environmental regulations. Just think – we could have had the Aprilia RS250 twenty years earlier, and with twice as much power and especially torque for not a huge amount more weight! Imagine what that might have been: a two stroke 500GP race replica with lights – and the Harley-Davidson name on the tank. If only….