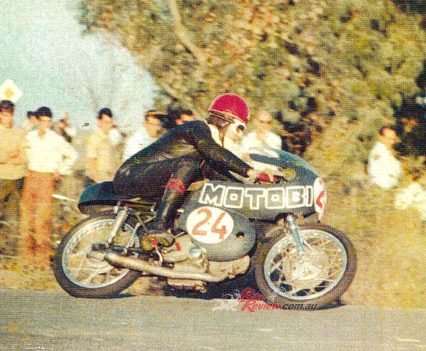

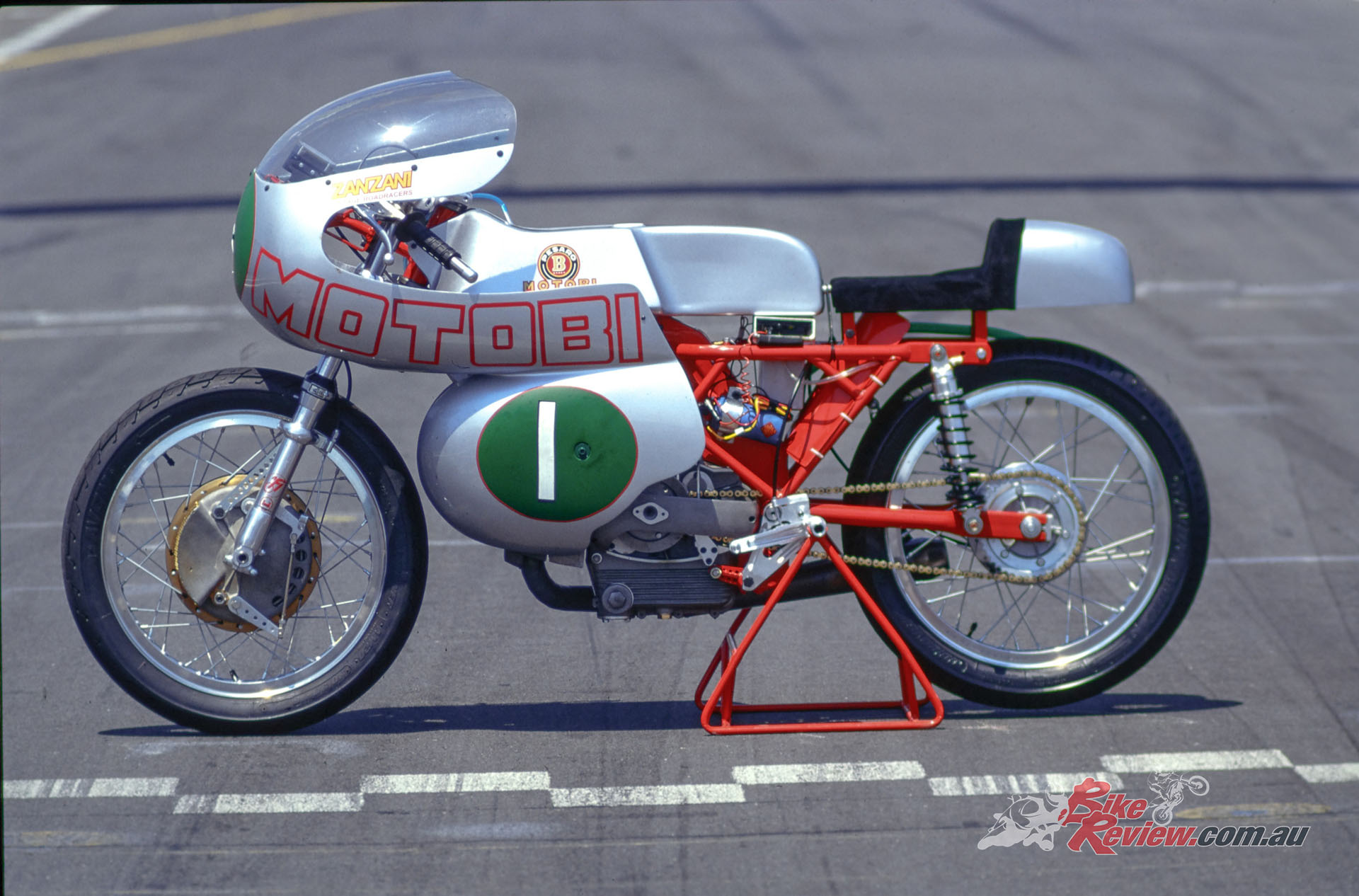

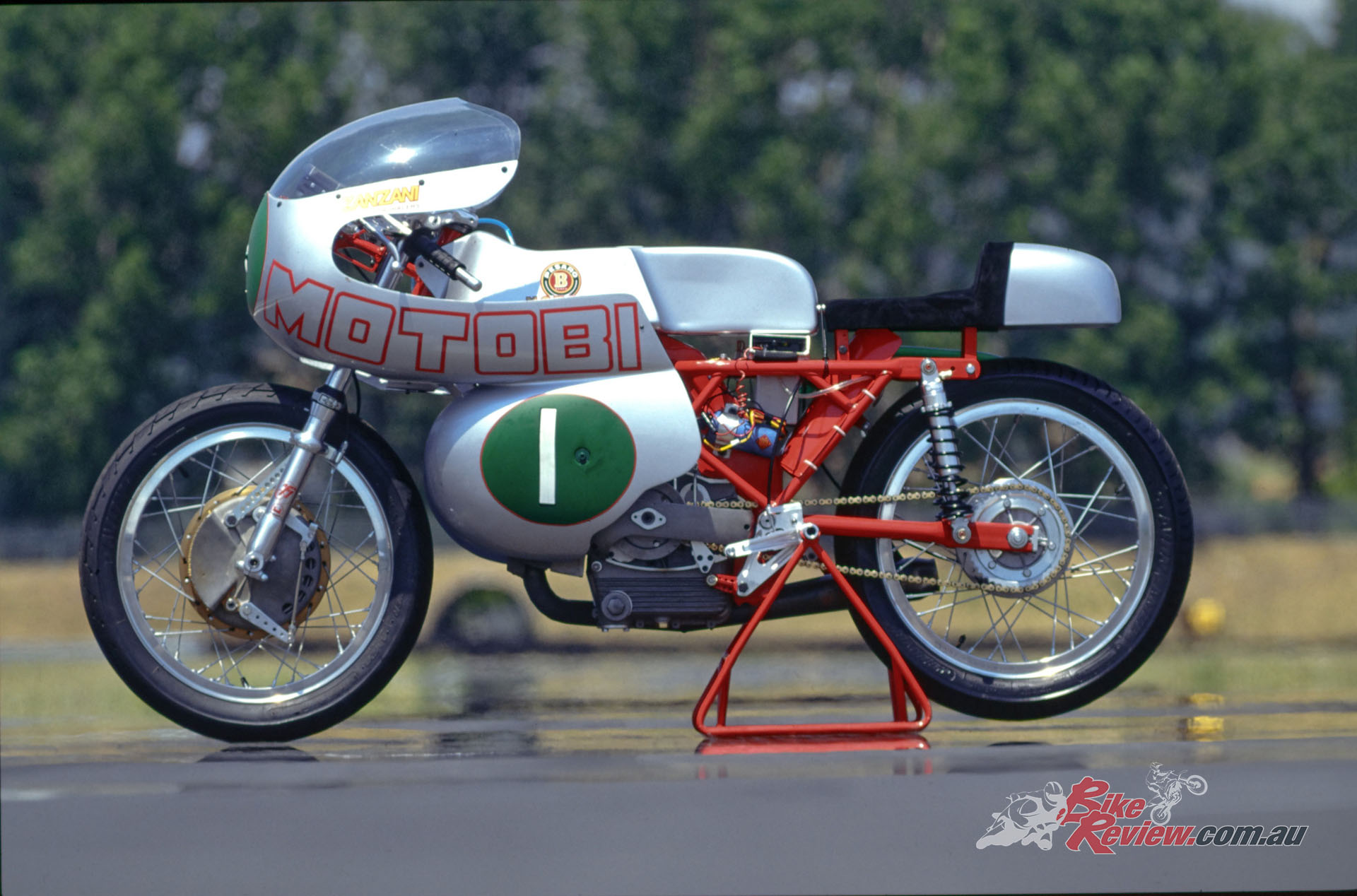

Cathcart had the chance to ride the spectacular MotoBi Sei Tiranti 250. These machines are built to original specifications by the original creator, Primo Zanzani... Photo credit: Kel Edge

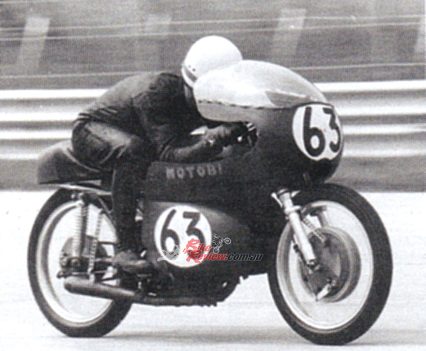

MotoBi, born out of a family dispute between the Benelli brothers before being absolved by the Benelli brand and brought to success in racing at the hands of Primo Zanzani. I had the chance to ride the incredible Sei Tiranti 250 in customer and factory trim…

MotoBi, born out of a family dispute between the Benelli brothers before being absolved by the Benelli brand and brought to success in racing at the hands of Primo Zanzani. Alan Cathcart had the chance to ride the Sei Tiranti 250…

Get up to date with the full MotoBi history here…

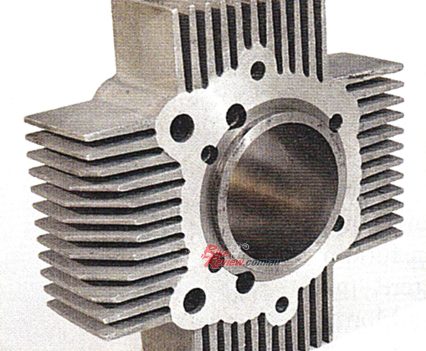

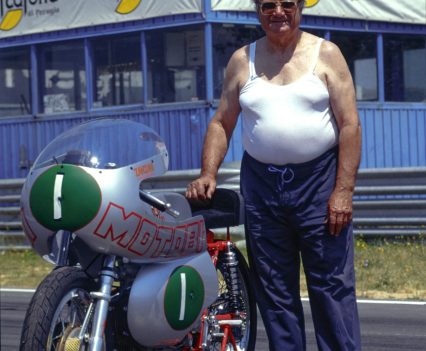

Zanzani created just nine examples between 1965 and 1973 of a limited edition homologation special known as the 250cc MotoBi Sei Tiranti (six-stud). This had six cylinder head studs instead of the street model Sprite’s four, to resolve problems with cylinder head sealing when compression and engine speeds were raised in pursuit of power – and considering that by the end of the decade Zanzani had more than doubled the 16hp output of the street 250 Sprite to 36hp in MSDS form.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

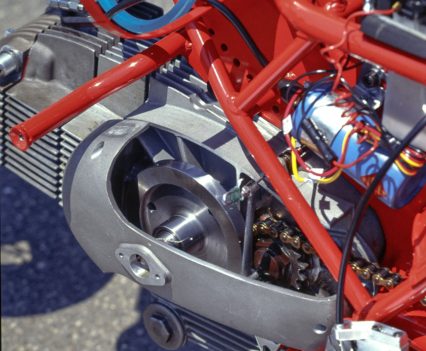

MotoBi saw some success, but the global Japanese onslaught meant diminishing sales and no budget for racing, so in 1970 the MotoBi factory race department was closed, leaving Zanzani to start his own machine shop operation in Pesaro, where he built another 15 Sei Tiranti racers in the early ’70s. But in parallel with this, Zanzani developed a specialist expertise in the disc brake technology then new to motorcycles, but which he’d been the first in the world to adopt on any GP racer back in 1965 on the four-cylinder Benelli 250, using US-made Airheart discs rather than the Campagnolo disc brakes then produced in Italy for lightweight 50/125GP machines.

Thereafter, together with his two sons Athos and Mirko, Primo Zanzani continued to run the trio of high-tech machine shops he owned in Pesaro, producing intricate components for the local woodworking machinery industry – and complete MotoBi 250 Sei Tiranti replicas! He passed away in November 2017, aged 93, after a long and productive, but also highly passionate life on two wheels.

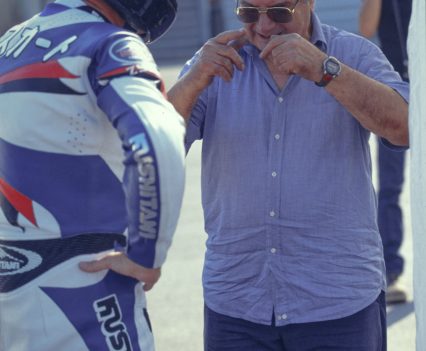

But before that, I’d come to know Primo during my regular visits to Italian race teams’ workshops, as well as track testing current GP racers fitted with his brakes. He was always eager to chastise me for having started my own racing career riding what he always termed the ‘anti-MotoBi’ Aermacchis which had copied the horizontal OHV cylinder format of the Pesaro brand’s singles, albeit without replicating the unique ‘eggcentric’ format of the Prampolini-designed MotoBi motor.

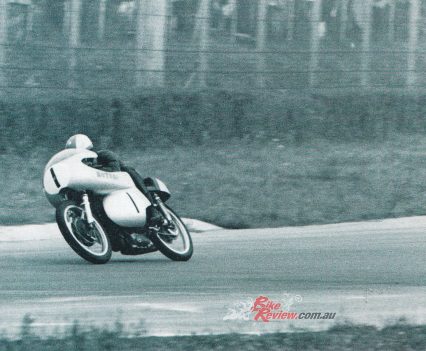

So when in the late 1990s Zanzani resumed building complete Sei Tiranti replicas for the flourishing Classic racing marketplace, he was eager I should try one out. Hence in the Italian summer of 1998 I took him up on his offer at the tight 2.51km Magione circuit near Perugia – an ideal track to sample the merits of these light, nimble four-stroke singles.

In the Italian summer of 1998, Cathcart took Primo up on his offer to ride the MotoBi at the tight 2.51km Magione circuit near Perugia – an ideal track to sample the merits of these light, nimble four-stroke singles.

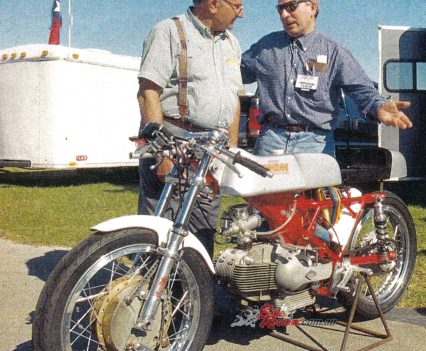

“I was asked to make so many parts for MotoBi enthusiasts either restoring or racing our original bikes from 30 years ago, that it seemed natural to consider building complete motorcycles again,” recounted Primo, bending to adjust the clutch on the latest of the five Sei Tiranti replicas he’d built so far in his Pesaro workshop, as we sheltered from the torrid summer sun in the shadow of the pits. “After all, I still had all the jigs and patterns from when I built them in the old days, so restarting production didn’t entail much preparation.”

Despite these machines being “replicas” the definition of a replica is hazy, considering they were built by Zanzani with the original jigs. They’re built exactly how they were intended to…

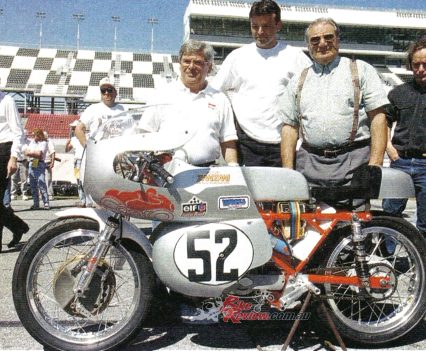

The fact that he also had access to original MotoBi parts stocks in both Italy and the USA – where, as proof that what goes around, comes around, Cosmopolitan Motors were marketing the modern Zanzani-built replicas to American historic racing enthusiasts – meant that Primo could deliver a brand-new 250 Sei Tiranti built to order at a price of $18,000USD, back then.

“Given that these were faithful in every detail to the original MotoBi Formula 3 MSDS design, they weren’t so much replicas as the resumption of manufacture of the original model…”

Given that these were faithful in every detail to the original MotoBi Formula 3 MSDS design, they weren’t so much replicas as the resumption of manufacture of the original model a quarter-century down the line – just like today’s continuazione versions of his dad’s 500cc Patons that Roberto Pattoni has been building for the past two decades.

To produce the modern Sei Tiranti, Zanzani took an original MotoBi pressed-steel spine frame (produced in large quantities and so readily available, since it was common to all the marque’s OHV four-stroke models), and reinforced it with his own tubular steel bracing, which just as back then effectively constituted a subframe attached to the main structure.

“We lengthened the wheelbase slightly by 30mm from standard to 1320mm in the 1960s with a special swingarm,” said Zanzani. “This was to improve stability on fast turns, and increase weight on the front wheel for extra grip in slower ones.”

The new bikes had the same mod, with twin Works Performance gas shocks sourced from the USA and available with a choice of springs to suit 70, 75 or 85kg rider weights. (Fortunately, I rode the bike at Magione before lunch!) The 35mm Ceriani fork was ubiquitous period hardware for a bike like this, with braking provided by a 210mm Fontana 4LS magnesium front drum and 160mm Grimeca 2LS rear, though with the complete bike weighing just 96kg complete with trademark ‘double-bubble’ fairing, and the fuel tank with its distinctive upward sweep to the steering head empty of fuel, there wasn’t so much to stop. Well, before you add in the rider, that is….

Actually, I fit the MotoBi better than I expected, and that’s not just because I spent so many seasons at the outset of my racing career riding its Aermacchi rival of similar slim, low-slung stature and cloned engine layout. For that had been some years earlier, and though I must admit that folding myself with some success around a Ducati Supermono of similar horizontal cylinder layout for the previous six years might have helped, the fact was that, as on so many Italian bikes, the ergonometrics of the MotoBi were such that a much taller rider than the star midgets it was designed for, could actually fit aboard quite well.

Despite the lightweight, compact nature of the MotoBi Sei Tiranti 250, Cathcart fit aboard quite well…

Italian designers have always been masters of packaging, and that was the case again here. And on the freshly constructed silver factory MotoBi racer, the choice of a wider WM2 Akront rim for the rear 110/80 Avon AM23 tyre prevented it feeling too nervous or light-steering. But a customer’s 1970s original bike I also sampled at Magione (which moreover had the footrests 50mm further forward, in streetbike mode, whereas the Sei Tirantis were all built as race bikes, with rearsets, said Zanzani) had the same tyre on a WM1 rim, with the result that it felt like riding my old Aermacchis on Dunlop triangulars – as in, distinctly twitchy!

The new racer felt more stable and steered well, just the nimble side of nervous, and great in Magione’s tighter turns, while adequately stable in the track’s one fast sweeper. But I did catch myself holding my breath as I cranked through that turn at speed – not because I frightened myself, but because you’re conscious that this is an ultra-agile motorcycle with not a lot of weight on the front wheel thanks to the 47/53 forward weight bias, which you want to avoid upsetting with any undue movement. Such as a sharp intake of breath, for example! Seriously, as I learnt from my Aermacchi days it pays to stay crouched down over the fuel tank on such a bike, to try help load up the front wheel via your body weight, for extra grip.

“The new racer felt more stable and steered well, just the nimble side of nervous, and great in Magione’s tighter turns, while adequately stable in the track’s one fast sweeper.”

The American rear shocks worked really well, helping deliver the ideal grip of the Avon tyres that are the benchmark products for today’s Classic racers, without any chatter or slides even in the torrid 35°C heat of our test day. But the 35mm Ceriani fork was too softly damped, producing a bounciness that could have been improved with heavier weight fork oil and/or more of it.

The 4LS Fontana front drum had quite a bit of bite, but only if you squeezed really hard, whereas the same brake on the customer bike I rode worked much better – probably because it wasn’t so new, and the linings had bedded in, but possibly because it had a different ratio on the lever pivot, as well as a longer lever. In any case, you needed to also use the small 160mm rear 2LS Grimeca to the max to make the bike stop well from any speed – just as on my series of Aermacchis, which riding the MotoBi reminded me so strongly of.

The 36hp@10,200rpm at the gearbox which the best of these produced compared favourably with the 38hp@10,500rpm at the rear wheel which Primo had extracted from the born-again MotoBi Sei Tiranti’s 74 x 58mm motor. But in the years after my test, Primo continued to wave his magic wand at the egg-shaped engine, so that by the time he passed away in 2016, he had extracted an amazing 42hp at the rear wheel from the 250cc version, while by dint of rearranging the architecture of the motor, he’d managed to find space to bore it out by 10mm to 84 x 58mm. In this 316cc guise it delivered 52hp – again at the rear wheel, still at 11,000rpm – and apparently with a linear torque curve from 5,000 to 11,000rpm. That’s quite a wand!

The 36hp@10,200rpm at the gearbox which the best of these produced compared favourably with the 38hp@10,500rpm at the rear wheel which Primo had extracted from the born-again MotoBi Sei Tiranti’s 74 x 58mm motor.

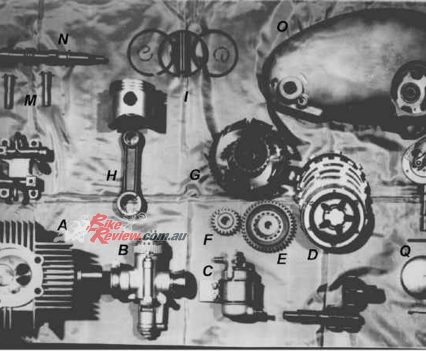

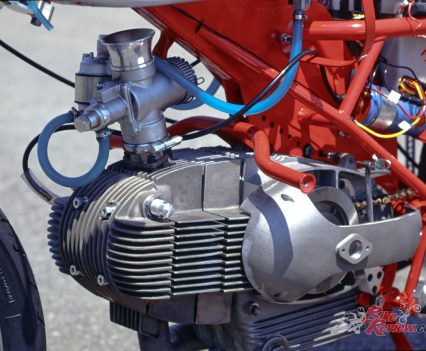

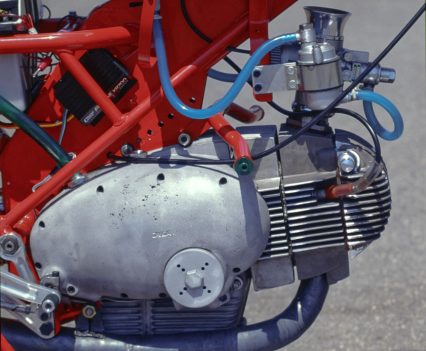

To achieve this, Zanzani took new sandcast crankcases with his name cast into them, and fitted a lightened and rebalanced roller-bearing crankshaft with external flywheel, a Carrillo conrod carrying a forged Asso piston delivering 11.1:1 compression, his own special C8 camshaft actuating competition aluminium pushrods, and peened and polished race rockers of a new design. The new cylinder carrying a cast iron sleeve was also sandcast, and carried one more fin on each of its four sides than before, for enhanced cooling.

The high compression O-ring cylinder head was ported and flowed, then fitted with oversize sodium-filled 40mm inlet and 34mm exhaust Zanzani valves made to aircraft quality, running in bronze valve guides, each fitted with dual US-made RG springs, and set at a 10-degree wider included angle of 58° compared to the road 250, because of their larger diameter (stock: 35mm/32mm). America also provided the Crane Cams electronic ignition running 44° of advance, which required a healthy 12v battery, while carburation came from a period 38mm Dell’Orto SS1 with remote float, and no idle jet. Add in a close-ratio five-speed Zanzani gearbox which retained the road bike’s oil-bath clutch as was required under period MSDS rules – and go. I did.

Well, only after finding a battery that worked properly and a hard enough plug to let the motor rev hard – but once that was sorted out, the MotoBi Sei Tiranti really delivered. It pulled pretty strongly from as low as 4,000rpm, which was a bit of a surprise, but then came a patch of megaphonitis which meant it was best to keep it turning above 7,000rpm even exiting tight turns, which could be achieved with a slight touch of the quite sensitive clutch lever to coax the revs out of it if you’d let it bog down. The carburettor slide and cable on this brand new bike were still rather sticky, meaning that in the absence of any graphite grease to free up the throttle, getting on the gas to drive hard out of a turn meant a rather jerky pickup via the Tomaselli quick turn GP throttle, as well as a stiff twistgrip action.

“The customer bike I also rode, fitted with a Zanzani Sei Tiranti motor, showed how well the package turned out.”

But the customer bike I also rode, fitted with a Zanzani Sei Tiranti motor, showed how well the package turned out, with an eager appetite for revs on this pushrod motor that I only ever remember seeing safely on my works-spec short circuit ultra short-stroke 350cc Aermacchi, not the longer-stroke standard ones I rode in the Isle of Man TT. The best compliment I could pay the Zanzani MotoBi was that riding it reminded me of that: judging by my Magione outing, his customers could enjoy 11,000rpm power deliveries reliably, and with a surprising turn of speed for a 250cc pushrod single of 220km/h at Monza, according to Primo.

“The best compliment I could pay the MotoBi was that riding it reminded me of that: judging by my Magione outing, his customers could enjoy 11,000rpm power deliveries reliably…”

But you had to rev it hard to get competitive power, making the fact that Zanzani held ample stocks of all spare parts for engine and chassis (except Akront wheel rims: don’t crash!) a good reason for buying a new bike from the man who made them back then, if you wanted to go Classic racing today with peace of mind.

“You had to rev it hard to get competitive power, making the fact that Zanzani held ample stocks of all spare parts for engine and chassis a good reason for buying a new bike from the man who made them back then…”

And that’s what many Zanzani customers have done since then, with considerable success, like Martin Hudson who won the UK’s CRMC 250cc Championship on his Zanzani-built MotoBi, or Australian Jonathan Houston, winner of countless 250 Classic races and titles on his similar bike since purchasing it in 2013. Other bikes have ended up in Japan, the USA (four of them), Ireland, Germany and of course, Italy. A copy of ‘my’ factory test bike which I rode at Magione would fly to Daytona the following March, where local Classic ace Dave Roper would set a 250GP pole time two seconds faster than the opposition – only to have the gearbox disintegrate in the next session, resulting in a DNS. Pity – but perhaps the 42 bhp Primo had By then extracted from the MotoBi engine was just too much for the transmission to handle!

Really, the Zanzani-built MotoBi 250 was the lightweight version of the replica Manx Nortons and 7R/G50s built today for the bigger classes, which dominate the grids of Classic races around the world. In delivering the same option to enthusiasts of the smaller capacity classes. Primo Zanzani was providing a service that others have followed since for other marques – albeit few of them with the same enthusiasm and unbroken line of heritage that his modern continuazione MotoBi Sei Tiranti racers undoubtedly represented.

MotoBi Sei Tiranti 250 Specifications

ENGINE: Air-cooled OHV pushrod single-cylinder four-stroke, 74 x 58mm bore x stroke, Crane Cams electronic CDI with 12v battery, 1 x 38mm Dell’Orto SS1 with remote float-chamber, Multiplate oil-bath clutch, 5-speed close-ratio Zanzani with straight-cut primary gear

CHASSIS: Pressed-steel central spine with tubular steel rear subframe, 35mm Ceriani telescopic fork (f) Tubular steel swingarm with 2 x Works Performance gas shocks (r) 210mm Fontana four leading-shoe drum (f) 160mm Ceriani twin leading-shoe drum (R) 90/90H18 Avon AM22 on 1.85 in/WM1 Akront wire-spoked aluminium rim (F) 110/80H18 Avon AM23 on 2.15 in/WM2 Akront wire-spoked aluminium rim (r). 1320mm wheelbase.

PERFORMANCE: 38hp@10,500rpm (at wheel, when tested), 220km/h top speed (Monza), 96 kg with oil/no fuel, split 47/53.

Owner: Primo Zanzani & Co., Pesaro, Italy www.motobi.com

MotoBi Sei Tiranti 250 Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.